Chapter 2

Service Strategy Principles

THE FOLLOWING ITIL INTERMEDIATE EXAM OBJECTIVES ARE DISCUSSED IN THIS CHAPTER:

- ✓ Service strategy basics

- Basic approach to deciding a strategy

- Strategy and opposing dynamics

- Outperforming competitors

- The four Ps of service strategy

- ✓ Services and value

- Services

- Value

- Utility and warranty

- ✓ Assets and service providers

- ✓ Defining services

- Eight steps to define services

- ✓ Strategies for customer satisfaction

- Kano model

- ✓ Service economics

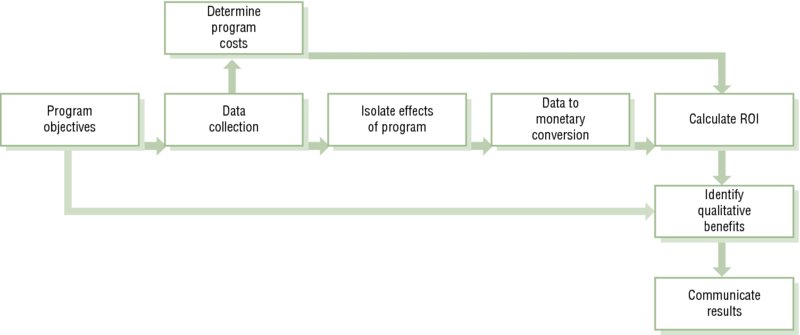

- Return on investment

- Business impact analysis

- ✓ Sourcing strategy

- ✓ Strategy inputs and outputs within the service lifecycle

To do well on the exam, you must ensure that you understand the basic principles of service strategy. These principles include the concepts of utility and warranty, service value and service economics. You will need to demonstrate that you can apply these concepts to the scenarios by analyzing the information provided in the exam questions.

To do well on the exam, you must ensure that you understand the basic principles of service strategy. These principles include the concepts of utility and warranty, service value and service economics. You will need to demonstrate that you can apply these concepts to the scenarios by analyzing the information provided in the exam questions.

Service Strategy Basics

This chapter covers the elements of service strategy that are necessary to understand, use, and apply the processes within service strategy to create business value. These concepts apply across the service lifecycle, but in this chapter we consider their relevance in service strategy. It will enable the use of the knowledge, interpretation, and analysis of service strategy principles, techniques, and relationships and the application for creation of effective service strategies.

Deciding on a Strategy

A strategy is a plan that enables an organization to meet a set of agreed objectives. It is important to establish the IT service management strategy for an organization so that the IT department is focused on meeting the needs and objectives of the organization as a whole and is not working in isolation.

To derive a successful IT service management strategy for the IT department, it is important to consider some key factors.

There are many sources for organizations to obtain their IT needs, and any strategic approach needs to recognize the potential competition. It should ensure that the IT department is in a position to exceed the performance of any outsourced suppliers or to be seen as delivering better value.

Whatever the desired objectives of the organization, the service provider should develop a strategy that recognizes the constraints under which it must operate.

This will enable the provider to establish the services that are required and the areas of the organization where they will be most effective. This can be expressed as the services offered and the markets served.

Strategy and Opposing Dynamics

It is necessary to understand the limitations of any strategic plan. These are often referred to as the opposing dynamics. In Figure 2.1, you can see a depiction of opposing dynamics.

Figure 2.1 Achieving a balance between opposing strategic dynamics

Copyright © AXELOS Limited 2010. All rights reserved. Material is reproduced under license from AXELOS.

Future vs. Present

This requires that we accommodate the pace of business change as business opportunities arise and disappear. The strategy has to be more than a plan and be able to adapt to the unforeseen.

Operational Effectiveness vs. Improvements in Functionality

Operational effectiveness should not be delivered at the expense of distinctiveness or the service provider may lose its customer base. There is a balance to be achieved here because although improvements increase competitive advantage, it is still important to deliver and provide the required functionality.

Value Capture

In the third dynamic, we are considering value capture. This refers to the value gained when innovations are launched versus the value captured during ongoing operations. Value capture is the portion of value creation a provider is able to keep. There is a very small window between the time an innovative feature is launched and the time the next competitor has the same capability. The service provider needs to be able to achieve a balance between introducing new functionality and maintaining normal practice.

Managing the balance between these opposing dynamics is critical for a successful service strategy. It is important for the service provider to understand the requirements of the organization and be able to react and predict, adapt, and plan to meet the changing needs of the business. Flexibility is a key attribute of the strategic approach.

Outperforming Competitors

The goal of a service strategy can be summed up as superior performance versus competing alternatives. A high-performance service strategy, therefore, is one that enables a service provider to consistently outperform competing alternatives over time and across business cycles, industry disruptions, and changes in leadership. It comprises both the ability to succeed today and positioning for the future.

Four Ps of Service Strategy

In 1994, Henry Mintzberg introduced four forms of strategy that should be present whenever a strategy is defined. These are illustrated in Figure 2.2 and are referred to as the four Ps of strategy.

Figure 2.2 Perspective, positions, plans, and patterns

Copyright © AXELOS Limited 2010. All rights reserved. Material is reproduced under license from AXELOS.

We will consider each of these in turn.

Perspective

Perspective is the vision and direction of the organization. A strategic perspective articulates what the business of the organization is, how it interacts with the customer, and how its services or products will be provided. A perspective cements a service provider’s distinctiveness in the minds of the employees and customers.

Positions

When we consider the position of a strategy, it should describe how the service provider intends to compete against other service providers in the market. The position refers to the attributes and capabilities that set the service provider apart from its competitors. Positions could be based on value or low cost, specialized services or providing an inclusive range of services, knowledge of a customer environment, or industry variables.

The framework considers a number of different types of positioning.

First, we look at variety-based positioning. This is where the service provider differentiates itself by offering a narrow range of services to a variety of customers with varied needs. For example, a cell phone company offers a range of predefined packages based on time and type of usage. Customers choose the package that suits them, even though they and other customers may use the same package differently.

Another option is that of needs-based positioning. The service provider differentiates itself by offering a wide range of services to a small number of customers. This type of positioning may also be called “customer intimacy.” The service provider identifies opportunities in a customer, develops services for them, and then continues to develop services for new opportunities or simply continues to provide valuable services that keep other competitors out. The relationship between the service provider and the customer is key in needs-based positioning. Examples here might be specialist service providers of medical systems in the pharmaceutical industry.

When a service provider targets a particular market and offers tailored services commonly based on a special interest or location, this is known as access-based positioning. Typically, only people in that group will have access to the service. For example, a service provider might offer branded items that can be bought in only a specific store or through a particular outlet, such as Harrods (London).

Last we consider demand-based positioning. As the name suggests, this is a type of positioning in which the service provider meets the demands of a customer by using a variety-based approach to appeal to a broad range of customers. The difference from variety-based positioning is that they allow each customer to customize exactly which components of the service they will use and how much of it they will use. This is an approach that is being explored by online service providers like Dropbox, which allows its customers to choose from different packages.

Plans

A strategy should be documented so that it is formally communicated throughout the organization. This is often the most tangible form of a strategy, a set of documents referred to as the strategic plan, and in many organizations this may be referred to as “the strategy.” The plan contains details about how the organization will achieve its strategic objectives and how much it is prepared to invest in order to do so.

To provide for an uncertain future, plans usually contain several scenarios, each one covering a strategic response and level of investment. Throughout the year, the plans are compared with actual events. This allows for adjustments to be made to adapt to any changes in the organizational requirements.

Some plans are high-level plans, such as the overall strategy, while others are more detailed, such as the execution plans for a particular new service or process. All plans should be coordinated and follow the same strategic framework.

Patterns

When we talk about patterns in service strategy, we are describing the ways in which an organization organizes itself to meet its objectives. The patterns could be organizational hierarchies, processes, interdepartmental collaboration, or services. Some patterns involve the way the organization works internally, whereas others involve the way in which the organization interacts with its customers and suppliers.

Recognizing patterns is important because they ensure that the service provider does not continuously react to demand in a new way every time. A pattern will enable the service provider to predict how a strategy will be met and forecast the investment that will be required.

There are two ways in which patterns can be formed. In some cases the organization will define the patterns it needs in its strategy. It will then define the way in which everyone complies with the patterns. In other cases, patterns that have been successful in the past will be formalized into the strategy of the organization. These are often referred to as emergent strategies.

Relationship between the Four Ps

We have already explored the way in which a service provider’s perspective and position will allow it to develop plans that, if executed, will ensure that the service provider achieves its strategic objectives.

However, planning involves the future, and even with the best intent, no plan can be fully reliable. Changes to the organization, its customers, and their respective environments can impact the successful execution of a plan. It is important that the service provider be flexible and not stick rigidly to a plan that is no longer valid. It may be necessary to alter the plan, defer it, or abandon it. In some cases, a service provider may have to merge plans or even create new ones. This is shown in Figure 2.3.

Figure 2.3 Strategic plans result in patterns.

Copyright © AXELOS Limited 2010. All rights reserved. Material is reproduced under license from AXELOS.

It is necessary to ensure that a strategy is not a rigid application of plans in a changing environment but is instead a continually adapting process, ensuring that the business and service provider stay relevant to a changing environment.

Services and Value

We are going to explore how the strategy for delivery of services is managed and what service management means for an organization.

Service

To refresh your memory, consider the definition of a service, as described in the framework.

A service is a means of delivering value to customers. Remember, customers are the people in an organization who pay for, or have financial authority over, what is delivered. The value is expressed in business terms, and it is the service provider’s responsibility to ensure that it enables the value to be realized. This is the facilitation of the outcomes while managing the costs and risks on the customers’ behalf.

When working on strategy, it is important to remember this definition because it should guide the thinking and decisions made by the service provider. Let’s continue to examine this definition.

It is important to remember that what we deliver in IT is not the same as something manufactured, like a physical product. There is a big difference between a service and a product.

Products are delivered as a fixed output, by a repeatable route. Consider the production environment of a factory. The output is produced by the application of a repeatable set of actions, taking raw materials and converting them to a physical end state. Value is created and realized through the exchange of the product between different parties—in other words, when the item is bought and sold.

A production environment also allows for stockpiling of products, which can be used at a later date. The value is maintained in the product itself, not its manufacture.

In contrast to products, services are dynamic interactions between customers and service providers reacting and responding to a real-time demand for a service. The output generated by a service is often variable, dependent on the scale and importance of the input. Think of the different transactions that can be generated by a single user, anything from a minor service request for a replacement of simple technology to the request for a complete new service.

This diversity of output means that we have to accommodate many different ways of delivering service. Consider the difference between a virtual transaction through a self-service portal and the human intervention still required for the physical repair of equipment.

The success of a service is based on the achievement of the customer’s desired outcome, not on whether or not the output of the service has been delivered. The value of a service is established only by its use to a customer. It is not the output of a service that is considered valuable but the customer’s ability to use its output to achieve their ends.

The result of this is that value can only be present in the relationship between customer and service provider. If there is no relationship, there is nothing to deliver, and there will therefore be no value.

This is often measured in terms of customer satisfaction, showing the importance of the relationship rather than a tangible product.

It is important to understand what we mean by an outcome—the ITIL guidance defines an outcome as “the result of carrying out an activity, following a process, or delivering an IT service.”

Outcomes are often described as either business outcomes or customer outcomes. Business and customer outcomes are differentiated by their context. Business outcomes represent the business objectives of both the business unit and the service provider and involve internal customers.

Customer outcomes are usually based on external service providers. For example, the external service provider may be focused on the outcome of delivering a profit, while the customer’s business outcomes will make use of the service to deliver their own requirements. Each will be able to fulfil their desired outcomes, but they do not have the same overall goal.

When we consider the difference between an outcome and an output, it’s important to remember that the definition of a service refers to an outcome, not an output. An output can be achieved, such as meeting service levels, but it may still result in customer dissatisfaction if the customer’s outcome is not met. Delivering a service requires the service provider to focus on the outcome desired by the customer and to track changes and adjust service accordingly.

Business outcomes are achieved when the business is able to perform activities that meet business objectives. They are defined in practical, measurable terms, as in the following examples:

- A product or service is delivered to a customer.

- An employee’s salary is paid.

- A financial report is submitted to a regulatory body.

- Taxes are collected.

- Cargo is shipped on a ship or airplane.

When we consider the responsibilities for specific costs and risks, it is important to remember that the focus for the customer is on outcomes and how the service will meet the needs. Customers are concerned about what a service will cost and how reliable it will be. The relationship between the service provider and the customer does not depend on knowing every expenditure item and risk mitigation measure that the service provider employs to deliver the service. The customer will assess value by comparing price and reliability with the desired outcome.

The service triangle (which associates the concepts of utility, warranty, and price to demonstrate value) shows the criteria that the customer will use to judge value and the service provider will use to deliver service. It is important that the service provider and the customer understand that the increase or decrease of any of these criteria will have an impact on the others. Delivering a lower-cost service will mean there is less capability for functionality and performance. The balance has to be achieved between the customer requirements and price, functionality, and performance. It is the responsibility of the service provider to capture the customer requirements while it determines the optimal approach for delivery. This includes the approach to risk and risk mitigation and the technology adopted to deliver the service.

In this way, the customer receives value, without the ownership of specific costs and risks.

Internal and External Customers

Services are delivered to both internal and external customers.

Internal services are delivered between departments or business units within the same organization, whereas external services are delivered to external customers.

To deliver value, the service provider must be able to differentiate between services that support an internal activity and those that achieve business outcomes, and understand the prioritization of each from the customer’s perspective. The activity to deliver the services may be similar, but internal services must be linked to external services before their contribution to business outcomes can be understood, measured, and prioritized. For example, email is important to an organization even though the organization manufactures cars as its main business. How well would the organization be able to function without this element of the desktop service? It may be the most important communication device for the entire organization and therefore should be prioritized accordingly.

The service provider can differentiate the types of service it delivers as described in the following sections.

Core Service

A core service is one that is fundamental to the delivery of a basic outcome required by a customer. It will deliver the value that the customer needs and is prepared to pay for. An example of this is the delivery of Internet banking functionality.

Enabling Service

An enabling service is a service that is needed in order for a core service to be delivered. Using the Internet banking example, an enabling service would be the network or the ISP provision. It is not normally something that an Internet banking user would consider or be aware of, but without it, the service could not be delivered.

Enhancing Service

An enhancing service is a service that is added to a core service to make it more exciting or enticing to the customer. Using the Internet banking example, this would be the provision of an additional feature such as the inclusion of a savings management program or the purchase of a financial savings package. It is not vital to the delivery of the core service, but it may make the service more attractive.

Value

Value can be expressed as the level to which a service will meet the customer’s expectations and is measured by how much the customer is willing to pay rather than the specific cost of the service.

The characteristics of value are that it is defined by the customer and delivers an affordable mix of features to meet the business requirements. It should enable the customer to meet its objectives and should be flexible to the changes that may take place within an organization over time. No organization will remain static in its requirements and objectives, and an IT service will cease to be perceived as valuable unless it can adapt to changing requirements.

In order to attribute value, the service provider needs to understand three specific inputs:

- What services were provided?

- What did the services achieve?

- What was their cost, or the price that was paid?

The answer to these questions will enable the service provider to demonstrate value to the customer. But the service provider will always be subject to the customer’s perception of value.

If we consider value from the perspective of the customer, then there are a number of factors that contribute to the understanding of value. This is shown in Figure 2.4.

Figure 2.4 How customers perceive value

Copyright © AXELOS Limited 2010. All rights reserved. Material is reproduced under license from AXELOS.

Calculating value can sometimes be a straightforward financial calculation: Does the service achieve what is required for an appropriate cost? If the cost does not impact profitability and the price remains competitive, then the service will be valuable.

As you can see, value is defined in terms of the business outcomes achieved and the customer preferences and perception of what was delivered.

Customers’ perceptions are influenced by the attributes of the service, their present or prior experiences, and the image or market position of the organization.

Preferences and perceptions are the basis for selecting one service provider over another, and often the more intangible the value, the more important the definitions and differentiation of value becomes.

Customers must have a value on which they will base their perception of value. This is known as the reference value. It is the perception mentioned previously, based on present or prior experience. The gains that are made from utilizing the service are perceived as a positive difference, an addition to the reference value. In an ideal situation, this would form the perception of value for the customer. But utilizing the service is not always perceived as a positive experience. An outage will create a negative difference, which detracts from the existing positive perception. This is shown as the net difference.

So in the final analysis, the perception of the economic value of a service will be the original reference value and the net difference. Any negative perception may have a significant impact on the overall perception of the service.

When developing the strategy for an IT service provider, it is useful to have a “marketing mind-set.” Marketing in this context refers not only to advertising services to influence customer perception, but also to understanding the customer’s context and requirements and ensuring that services are geared to meeting the outcomes that are important to the customer. Rather than focusing inward on the production of services, there is a need to look from the outside in, from the customer’s perspective.

A marketing mind-set begins with simple questions:

- What is our business?

- Who is our customer?

- What does the customer value?

- Who depends on our services?

- How do they use our services?

- Why are our services valuable to them?

To understand value chains and value realization, it is necessary to recognize that to be delivered, a service comprises multiple components. Each component is managed by a department within IT. Money is spent to procure, develop, and maintain each component, and each department manages their components to make sure they are operating correctly and therefore adding value to the service. Each piece of the jigsaw needs to make a positive contribution in terms of value added. The amount spent on the component should be less than the value it adds to the service.

Unfortunately, the true value can be calculated only after the value has been realized. This will only occur when the customer achieves its desired outcome.

If the value realized is not greater than the money spent, then the service provider has not added any value. It has spent money and in effect made a loss.

If IT wants to show it is adding value, it needs to link its activities to where the business realizes value. If it cannot do this, it will be perceived as a money spending organization. The IT money pit!

The only way to improve IT’s position is to reduce the amount of money thrown into the pit and cut costs! This will result in IT’s value reducing further.

The only way out of this destructive loop is to link services to business outcomes and show how each activity within IT helps to achieve each business outcome.

It is difficult to prove the value that has been added, particularly if there is no baseline or experience to benchmark against. Attempts can be made to explain what is being done to achieve the outcome, but a customer may simply view this as a way to drive up the price.

Ideally, the provider should focus on building a model where the contribution of each internal service can be measured and then link this to the achievement of the customer’s business outcome.

It is important that the IT provider understands the contribution provided by the internal service in terms of the utility or warranty it provides. This needs to be recognized in the context of the output the customer will receive and therefore the outcome they can achieve. Their perception of the value of the service will be positively influenced.

Capturing value will be the basis for effective communication of utility and warranty to improve customer perception of value and to provide a structure for the definition of service packages.

Utility and Warranty

Utility and warranty define services and work together to create value for the customer.

Utility

Utility affects the increase of possible gains from the performance of customer assets and the probability of achieving desirable business outcomes.

Figure 2.5 illustrates an example of an airline baggage handling service, which is able to load baggage onto an aircraft within 15 minutes 80 percent of the time. This is shown by the light-colored curve. With new security legislation, they will be required to perform additional security checks and to record the location of each bag in the aircraft hold. These additional activities require changes to the utility of the services.

Figure 2.5 Utility increases the performance average.

Copyright © AXELOS Limited 2010. All rights reserved. Material is reproduced under license from AXELOS.

In response to these new requirements, the airline changes the service to be able to do the additional work and is still able to load baggage onto the aircraft within 15 minutes 80 percent of the time. This new level of utility is shown by the dark-colored curve. The standard deviation remains the same since the warranty has not changed.

Warranty does not automatically stay the same when utility is increased. In fact, maintaining consistent levels of warranty when increasing utility usually requires good planning and increased investment. More investment is required for making changes to existing processes and tools, training, hiring additional employees to do the increased work, obtaining additional tools to perform newly automated activities, and so on.

Thus, the utility effect means that, although the customer assets perform better and the range of outcomes is increased, the probability of achieving those outcomes remains the same. This can be seen in the diagram; the shape of the graph and the space under the line remain the same.

Warranty

The effect of improving warranty of a service means that the service will continue to do the same things but more reliably. Therefore, there is a higher probability that the desired outcomes will be achieved, along with a decreased risk that the customer will suffer losses due to variations in service performance. Improved warranty also results in an increase in the number of times a task can be performed within an acceptable level of cost, time, and activity. Customers are interested in reliability and the impact of losses rather than the possible gains from receiving the promised utility.

Figure 2.6 shows how the standard deviation of the performance of a service changes when warranty is improved.

Figure 2.6 Warranty reduces the performance average.

Copyright © AXELOS Limited 2010. All rights reserved. Material is reproduced under license from AXELOS.

The lighter line shows that a significant percentage of service delivery is outside of the acceptable range. By making various improvements (e.g., training, process, and tool improvement; new tools or processes; automation), the service provider is able to increase the probability that the service will be performed within an acceptable range.

Using the airline baggage handling example, suppose that one year after adding the new utility, the airline would like to increase its “on-time departure” rate. Achieving this means that baggage handling needs to improve its performance. Without adding any new utility, the baggage handling service finds a better way of scanning and recording the location of bags. As a result, the baggage handling service is able to complete the loading of baggage onto the aircraft within 15 minutes 90 percent of the time—a significant improvement.

Combined Utility and Warranty

In Figure 2.7, you can see the impact of utility and warranty and how investment can be allocated according to the importance of the utility and warranty provided.

Figure 2.7 Combined effects of utility and warranty on customer assets

Copyright © AXELOS Limited 2010. All rights reserved. Material is reproduced under license from AXELOS.

In the bottom-left quadrant, you can see low business impact with variable utility and warranty bias:

- This is showing assets with little value even with utility and warranty.

- This shows that minimal investment in the asset and the utility and warranty is justified, or there is an option to retire the service.

In the top-left quadrant, the diagram shows low business impact with low utility and high warranty:

- This shows the asset deriving little value because service does not meet needs regardless of the high level of warranty.

- It shows that investment should be reallocated to improve utility.

In the bottom-right quadrant, the diagram shows high business impact with high utility and low warranty:

- Again, the value is low because the service does not perform well even with high utility.

- This time the investment needed will be to improve the warranty of service.

In the top-right quadrant, you can see high business impact with balanced utility and warranty:

- Any bias to utility or warranty will be highly visible because the outcomes are valuable to the business.

- This justifies optimum investment in the “zone of balance.”

Once we reach an appropriate balance between utility and warranty, customers will see a strong link between the utilization of a service and the positive effect on the performance of their own assets, leading to higher return on assets. This is shown in Figure 2.8.

Figure 2.8 Value of a service in terms of return on assets for the customer

Copyright © AXELOS Limited 2010. All rights reserved. Material is reproduced under license from AXELOS.

The arrow marked with a + (plus sign) in the diagram indicates a directly proportional relationship; here, the higher the utility, the higher the performance average. The arrow with a – (minus sign) indicates an inversely proportional relationship; here, the higher the level of warranty, the lower the performance variation.

In the diagram, services with a balance between utility and warranty increase the average performance of the customer assets. We could say that they will result in higher-value outcomes. This will also have the effect of reducing the performance variation, increasing the reliability of the service.

The combined effects of utility and warranty will enable the customer assets to achieve the customer’s business outcomes and result in a return on their assets. In other words, value is realized.

Communicating both utility and warranty is important for customers to be able to calculate the value of a service.

Communicating Utility

Communicating utility will enable the customer to determine the extent to which utility is matched to their functionality requirements.

Communicating utility in terms of ownership costs and risks avoided means that the service provider should be able to articulate the following points:

- That the service enables the business to achieve the desired outcomes more efficiently. This allows the business to reduce its costs (and in commercial organizations, to increase its profit margins).

- That the service improves the reliability of outcome achievement. In other words, the service mitigates the risk of the business not being able to achieve its outcomes.

Communicating Warranty

Warranty ensures that the utility of the service is available as needed with sufficient capacity, continuity, and security—at the agreed cost or price. Customers cannot realize the promised value of a service that is fit for purpose when it is not fit for use.

Warranty in general is part of the value proposition that influences customers to buy. For customers to realize the expected benefits of manufactured goods, utility is necessary but not sufficient. Defects either make a product unavailable for use or reduce its functional capacity. Warranties assure that the products will retain function for a specified period under certain conditions of use and maintenance. Warranties are void outside such conditions; normal wear and tear is not covered. Most important, customers are owners and operators of purchased goods.

Service providers communicate the value of warranty in terms of levels of assurance. Their ability to manage service assets instills confidence in the customer about the support for business outcomes. Warranty is stated in terms of the availability, capacity, continuity, and security of the utilization of services.

Usability refers to whether users can actually perform the required actions and access the information they need in order to be able to achieve the desired outcomes. For example, factors of usability may include readability of text, whether data entry is straightforward and logical, and so on.

The ability to deliver a certain level of warranty to customers by itself is a basis of competitive advantage for service providers. This is particularly true where services are commoditized or standardized. In such cases, it is hard to differentiate value largely in terms of utility for customers. When customers have a choice between service providers whose services provide more or less the same utility but different levels of warranty, they prefer the greater certainty in the support of business outcomes, provided it is offered at a competitive price and by a service provider with a reputation for being able to deliver what is promised.

One point to bear in mind when defining both utility and warranty is the affordability of the service. A service provider can build a perfect service, but the utility and warranty need to be balanced against what the customer can afford to pay. Affordability is a good way for customers to prioritize the elements of warranty and utility, given the outcomes they want to achieve.

Strategic Assets and Service Providers

We have explored the concept of value and begun to relate this to the customer, service, and assets. The following sections consider the way IT services are created and how value is delivered to the customers through the use of assets, resources, and capabilities.

How do the assets that make up an IT service relate to resources and capabilities, and what relevance does this have to the service management strategy?

Business Units and Service Providers

We will now examine the relationship between the assets used by business units and those used by service providers. Specifically, we are going to look at how these assets are related to services and the creation of value.

Business Unit

ITIL describes a business unit as an organizational entity, led by a manager, that performs a defined set of business activities that create value for customers in the form of goods and services.

The goods or services are produced and delivered using a set of assets, referred to as customer assets. Customers pay for the value they receive, which ensures that the business unit maintains an adequate return on assets. The relationship is good as long as the customer receives value and the business unit recovers costs and receives some form of compensation or profit.

It is the responsibility of the business unit to create value, which is determined in the context of the customer and the customer’s assets.

Service Provider

While some organizational units are business units, some are clearly service providers. A service provider is an organizational entity, led by a manager, that performs a defined set of activities to create and deliver services that support the activities of business units.

Service providers use service assets to deliver services to business units, and these service assets are used to enhance the performance of business assets to achieve business outcomes.

If there are constraints that affect the ability to deliver services, an investment in both resources and capabilities may be required to overcome them.

Suppliers may be included in this value chain, and they will need to invest in their own resources and capabilities to deliver according to the service provider’s requirements. But in service strategy, the focus for the service provider is the business outcome and how this can be established.

Service Asset

In Figure 2.9, you can see the representation of service assets driving services.

Figure 2.9 Service assets drive services to achieve business outcomes.

Copyright © AXELOS Limited 2010. All rights reserved. Material is reproduced under license from AXELOS.

Constraints will have an effect on the service that is delivered, either positive or negative, and this in turn will have an impact on customer assets and the ability to achieve business outcomes.

All organizations have some restrictions on the use of their assets. No organization has unlimited resource, and this will necessarily have an impact on the capability of delivery.

Other constraints may force the use of better-quality components—an example here would be security or regulatory requirements driving an improved capability in service.

IT Service Management

When we consider IT service management in the context of customer and service assets, it is the management of the service assets (resources and capabilities) used to deliver services that support the achievement of the customer’s business outcomes. Customers could be external or internal.

Service management enables the service assets to perform according to customer requirements while identifying and reducing the impact of constraints on the service assets. IT service management does this by managing IT’s capabilities and resources. This is done either internally or through the support of external service providers and technology vendors.

Achieving this is not straightforward and often takes several years of hard work and cultural change. Changes in the capability of staff and the resultant experience that they will gain takes time to develop.

Most IT service providers start out by organizing their departments according to technical specialization. This is an important principle because each type of technology is very specialized and requires people with specialized skills to manage it.

But this means that goals are accomplished and reporting is done in silos, and the selection of staff is based on expertise, not any strategic plans. Often functional managers compete with each other rather than act in partnership, and as a consequence, issues that affect the organization across the functions are not addressed.

Processes are used as a means for managing silos, to bridge the gaps between the departments. Processes can be self-contained or cross-functional, dependent on the outcome that is required. They should enable thinking of IT as a set of cohesive resources and capabilities, not just as a set of individual departments or specialisms.

It is important that the processes focus on outcomes, not just outputs. Otherwise, the individual departments will simply focus on their specific output and ignore the fact that the outputs produced by all are used to deliver the overall outcome required by the business.

To achieve this successfully, IT priorities must be aligned to the drivers of business value, otherwise the IT department will be entirely inwardly focused.

IT Service Provider

The logical conclusion of this engagement between business units, service management, processes, and IT departments is that the IT department models itself as a service provider, with the goal of meeting business outcomes.

As can be seen in Figure 2.10, the resources and capabilities of the service provider are utilized to support the service (in the context of utility and warranty), and these in turn support and enable the business unit. Use of customer assets in the form of resources and capabilities will deliver the business outcomes.

Figure 2.10 How a service provider enables a business unit’s outcomes

Copyright © AXELOS Limited 2010. All rights reserved. Material is reproduced under license from AXELOS.

This is a direct connection from the service provider on the right of the image to the business outcomes on the left. Management of service assets by the service provider is used to deliver the utility and warranty, with the positive and negative effects of risks and costs driving the use of assets, both for the service provider and the customer.

This is often viewed as an end-to-end approach for the delivery of service.

Working backwards from the service potential ensures that any strategic decisions are based on customer value.

Here are some key questions to ask to ensure that the service provider will deliver the business outcomes:

- Who are our customers?

- What do those customers want?

- Can we offer anything unique to those customers?

- Are the opportunities already saturated with good solutions?

- Do we have the right portfolio of services developed for given opportunities?

- Do we have the right catalog of services offered to a given customer?

- Is every service designed to support the required outcomes?

- Is every service operated to support the required outcomes?

- Do we have the right models and structures to be a service provider?

- What we are trying to achieve as a service provider? Are our customers happy?

- Do they view our services as strategic assets?

We know that assets are resources and capabilities that are used to deliver services. A strategic asset is any asset (customer or service) that provides the basis for core competence, distinctive performance, or sustainable competitive advantage or that qualifies a business unit to participate in business opportunities. It is an asset that makes a significant difference to the organization.

Strategic assets are dynamic in nature. They are expected to continue to perform well under changing business conditions and objectives of their organization. That requires strategic assets to have learning capabilities, and that means being able to learn from past experience.

Part of service strategy is to identify how IT and IT service management can be viewed as strategic assets rather than an internal administrative function. It is important that IT is able to link its services to business outcomes, which in turn will contribute to the organization’s competitive advantage and market differentiation.

We begin to grow service management into a strategic asset by building on our capabilities. This perception of IT as a valuable and trusted strategic part of the business does not happen overnight. It takes a concerted and formal effort in which IT demonstrates its contribution one area at a time.

Each new challenge that IT enables the business to overcome allows IT to develop additional credibility and enables the business to see IT as a strategic service provider. The more trusted IT becomes, the more services the business will ask it to provide, and at higher service levels. This increase in credibility and trust will justify more investment in the IT department, which in turn will allow for investment in greater capability.

Confidence and credibility in a provider have to be earned. Figure 2.11 represents cycles of earning trust. In practice there will be many more. It is of course possible for the cycle to run backwards if you fail to provide the service the business expects.

Figure 2.11 Growing service management into a trusted strategic asset

Copyright © AXELOS Limited 2010. All rights reserved. Material is reproduced under license from AXELOS.

The sequence of activity is as follows:

- Within an existing IT service provider, the cycle begins when the service provider and business have selected an opportunity—which could be an existing service or an initiative that has already been defined. The value of this opportunity is defined in terms of outcomes that need to be achieved and the investment required to meet them. The opportunity will also specify which customers and market spaces the opportunity addresses.

- The service provider ensures that the capabilities and resources are in place to deliver the service(s).

- When delivered at the agreed levels, these services enable the business to achieve its objectives or overcome the defined challenge. It is important that these achievements are documented and reported to the stakeholders.

- The customer recognizes the IT service provider’s contribution to their success (the value of the service).

- As a result, the customer is willing to entrust even more opportunities to the service provider.

Service management is viewed as a strategic asset (rather than a set of purely operational processes) when it can demonstrate how it enables the service provider to compete and differentiate itself effectively.

Service management does this by performing the following actions:

- Establishing a catalog of services that contribute to strategic business objectives and outcomes

- Identifying the market spaces in which IT enables the business to compete

- Defining how these services meet business challenges and then measuring them to ensure that this is achieved

- Building capabilities and resources to deliver these services and overcome identified challenges

- Communicating with the business about delivery achievements

Types of Service Providers

There are many options in the market place for the type of service provider an organization might use, and each has its own risks, costs, and benefits. This means that any choices made in sourcing IT from a service provider will need to align to the overall business strategy.

We will need to consider resources and capabilities and the overall outcomes that are required from the service provider, just as we do for a service that they deliver.

Type I Service Provider

The example in Figure 2.12 shows the Type I service provider. Type I providers are service providers that are dedicated to, and often embedded within, an individual business unit. The business units themselves are usually a part of an organization. They are funded by overheads and are required to operate strictly within the mandates of the business. Type I providers have the benefit of working closely with their customers, and are able to avoid certain costs and risks associated with conducting business with external providers. The control of all services remains within one organization.

Figure 2.12 Type I providers

Copyright © AXELOS Limited 2010. All rights reserved. Material is reproduced under license from AXELOS.

Because Type I service providers are dedicated to specific business units, they are required to have an in-depth knowledge of the business. They are usually highly specialized, often focusing on designing, customizing, and supporting specific applications or on supporting a specific type of business process.

The diagram shows three business units with Type I service providers. Each IT unit is dedicated to a single business unit and delivers specialized services to that business unit only. A disadvantage of this approach is that there may be duplication and waste when Type I providers are replicated within the organization.

Competition for Type I providers is from providers outside the business unit, such as corporate business functions, who may be able to utilize advantages such as scale, scope, and autonomy.

Type II Service Provider

Functions such as finance, IT, human resources, and logistics are not always at the core of an organization’s competitive advantage. Instead, the services of such shared functions are consolidated into an independent special unit called a shared services unit as shown in Figure 2.13. IT is shown as a single department with a service catalog that is available to multiple business units.

Figure 2.13 Common Type II providers

Copyright © AXELOS Limited 2010. All rights reserved. Material is reproduced under license from AXELOS.

Shared service units can create, grow, and sustain an internal market for their services and model themselves along the lines of service providers in the open market. Often they can leverage opportunities across the organization and spread their costs and risks across a wider base. They are subject to comparisons with external service providers whose performance they should match, if not exceed.

Type II providers can offer lower prices compared to external service providers by leveraging internal agreements and accounting policies. They can standardize their service offerings across business units and use techniques such as market-based pricing to influence demand patterns. Market-based pricing is the approach where the service provider compares itself to an external provider for its pricing model. This makes comparison easier for the customer and may highlight internal economies. A successful Type II service provider can find itself in a position where it is able to provide its services externally as well as internally.

It is possible to combine Type I and Type II within an organization where there is a mix of requirements for IT services—for example, some specialists and dedicated service provisions and some shared services.

Type III Service Provider

A Type III service provider is a service provider that provides IT services to external customers. In Figure 2.14, you can see an example of a Type III provider.

Figure 2.14 Type III providers

Copyright © AXELOS Limited 2010. All rights reserved. Material is reproduced under license from AXELOS.

The business strategies of customers sometimes require capabilities more readily available from a Type III provider. Type III providers assume additional risk because their core business is the delivery of service and they are competing against internal Type I and Type II providers. Type III providers can offer competitive prices and drive down unit costs by consolidating demand from a range of clients. They may have the economies of scale to be able to deliver against specialisms that are too expensive for an individual customer by offering the capability to a wider range of customers. A further aspect of Type III service providers is that they provide specific capabilities or activities that are used by a Type I or II service provider to support their services.

Although this is not shown in the diagram, it should be noted that organizations using Type III service providers will still need an internal IT function or functions to manage the specification of services, coordinate the contracts, and ensure that business outcomes are met.

Evaluation of Service Providers

An organization needs to understand the advantages and disadvantages of each provider type. The choice of provider will be influenced by a number of factors, including the cost per transaction with the service provider, the best practice in a particular industry sector, and any specific requirements that can be met by only a particular type.

Of course, a major consideration should be the core competencies that are delivered by the service provider. The decision will need to take into consideration the service provider’s risk management capabilities and the impact that the use of a specific provider type might have on the organization and the resultant risk. Another factor to consider is the economy of scale the service provider can deliver.

The tendency is for core services to be delivered by Type I or Type II providers (or indeed a mix of these), while enhancing services are often supplied through Type II or Type III providers (or a mix, as before).

It is important to remember that the organizational requirements may change over time, and this may have an impact on the sourcing model that is required. In Table 2.1, we have an organizational view of the movement from one service provider type to another. For example, changing from a Type I provider (left-hand column) to a Type III provider (right-hand column) would be classified as outsourcing.

Table 2.1 Customer decisions on service provider types

| From/to | Type I | Type II | Type III |

| Type I | Functional reorganization | Aggregation | Outsourcing |

| Type II | Disaggregation | Corporate reorganization | Outsourcing |

| Type III | Insourcing | Insourcing | Value net reconfiguration |

Evaluation of the service provider types depends on the nature of the provision, and whether customers keep a business activity in-house (aggregate), separate it out for dedicated management (disaggregate), or source it from outside (outsource) will depend on the answers to the following questions:

- Does the activity require assets that are highly specialized? Will those assets be idle or obsolete if that activity is no longer performed?

- If yes, then disaggregate and/or outsource.

- How frequently is the activity performed within a period or business cycle? Is it infrequent or sporadic?

- If yes, then outsource.

- Does the activity require knowledge specific to a particular business unit, even if the activity is infrequent and/or specialized?

- If yes, then disaggregate or insource.

- How complex is the activity? Is it simple and routine? Is it stable over time with few changes?

- If it’s stable over time, then outsource. If it is complex and volatile, it might need to be disaggregated.

- Is it hard to define good performance?

- If yes, then aggregate.

- Is it hard to measure good performance?

- If yes, then aggregate.

- Is it tightly coupled with other activities or assets in the business? Would separating it increase complexity and cause problems of coordination?

- If yes, then aggregate.

Organizations learn and improve over time during lasting relationships with customers. Fewer errors are made, investments are recovered, and the resulting cost advantage can be leveraged to increase the gap with competition. This is the same for the relationship between the service provider and their customers.

It is a fact that customers find it less attractive to turn away from well-performing incumbents, simply because of the costs relating to switching to a new provider. Experience can be used to improve assets over time and therefore improve the service delivery.

Service providers must therefore focus on providing the basis for a lasting relationship with customers. It is important for the service provider to carry out strategic planning and control to ensure that common objectives drive everything that is delivered. This requires knowledge to be shared effectively between units and the results of experience fed back into future plans and actions.

Defining Services

ITIL suggests eight steps that are needed for the service provider to be able to define a service. These steps outline how to identify customers and their requirements and whether there is an opportunity that a service provider can fulfil.

- Define the market and identify customers.

- Understand the customer.

- Quantify the outcomes.

- Classify and visualize the service.

- Understand the opportunities (market spaces).

- Define services based on outcomes.

- Service models.

- Define service units and packages.

Step 1: Define the Market and Identify Customers

When we talk about markets in this context, we mean the group of customers to whom the service provider is going to deliver services. So the first step has to be understanding the nature of the customer we are going to serve, as this will help us understand the options available.

For example, a Type I service provider will typically serve only one business unit. Their entire market consists of a single internal customer.

Markets can be defined by one or more criteria:

Industry Sector For example manufacturing, retail, financial services, healthcare, or transportation.

Geographically By a specific country or region. A service provider may provide a best-in-class service but decide to limit its availability to a single geographical region. A different service provider may provide a lower standard of service but deliver it consistently across multiple regions. This would make it easier for a customer to standardize its services across multiple regions.

Demographic The service provider may deliver a service geared toward a specific cultural group (e.g., television programming for a Spanish-speaking customer in the United States) or a group of customers with similar incomes (e.g., luxury or economy services).

Corporate Relationships Some service providers have specifically been set up to provide services to a group of companies with common shareholders and may not market those services to competitors of those companies.

Whatever the criteria, identifying the markets in which the service provider will operate is an important part of identifying which services the service provider will deliver and to which customers.

Step 2: Understand the Customer

For internal service providers, understanding the customer means understanding the overall business strategies and objectives of the organization and how each business unit meets them. It also means understanding the business outcomes that each business unit needs to achieve.

For an external service provider, understanding the customer means recognizing why they need the service they are purchasing. The service provider does not have to comprehend the detailed strategy, tactics, and operations of the customer, but they do need to understand the reasons the customer needs the service and what features are important.

Understanding customers involves understanding their desired business outcomes, their assets and constraints, and how they will perceive and measure value.

Desired Business Outcomes

The customers use their assets to achieve specific outcomes. Understanding what these outcomes are will help the service provider define the warranty and utility of the services and prioritize service needs.

Customer Assets

Services enable and support the performance of the assets the customer uses to achieve its business outcomes. Therefore, it is necessary when defining services to understand the linkage between the service and the customer assets.

Constraints

Customer assets will be limited by some form of constraint, such as lack of funding, lack of knowledge, regulations, and legislation. Understanding those constraints will enable the service provider to define boundaries for the service and also help the customer overcome, or work within, many of them.

How Value Will Be Perceived and Measured

Customers always measure performance, quality, and value. It is vital that the service provider understands how the customer measures the service—even if the service provider is not able to measure the service the same way.

The value of a service is best measured in terms of the improvement in business outcomes. These should be attributable to the impact of the service on the performance of business assets. Some services increase the performance of customer assets, some maintain performance, and others restore performance following an incident. A major aspect of providing value is preventing or reducing the variation in the performance of customer assets.

Step 3: Quantify the Outcomes

In this step, the service provider will work with the customer to identify its desired outcomes. These definitions need to be clear and measurable, and they need to be something that can be linked to the service.

Defining outcomes is an important part of defining services, but customers may take it for granted that everyone understands their particular outcomes because they are part of their normal routine. It is therefore important that the service provider work with the customer to quantify each outcome and document it.

Understanding how services impact outcomes, and therefore what type and level of service is needed, will require the service provider to map the services and outcomes. A good business relationship management process will help the service provider define and document the outcomes in terms that can be measured by the service provider. Mapping of outcomes to services and service assets can be accomplished as part of a configuration management system (CMS) and the service portfolio. Information on services is captured in the service portfolio, particularly the service catalog and service pipeline. Service level agreements also contain service information about how the service is linked to the business outcome.

Gaining insight into the customer’s business and having good knowledge of customer outcomes is essential to developing a strong business relationship with customers. This is a key activity within business relationship management.

An outcome-based definition of services ensures that managers plan and execute all aspects of service management entirely from the perspective of what is valuable to the customer. Such an approach ensures that services not only create value for customers but also capture value for the service provider.

Step 4: Classify and Visualize the Service

Every service is unique, but many have similar characteristics. If a new service shares common characteristics with an existing service, it will be easier to determine what it will take to deliver the new service. If it has no characteristics in common with existing services, it will need to be evaluated and designed from the beginning.

Creating a way to classify services and represent them visually can help in identifying whether a new service requirement fits within the current strategy or whether it will represent an expansion of that strategy. It might also assist the service provider in deciding not to make an investment in a service that moves it away from its strategy.

One way to carry out this classification of services is to use service archetypes, or basic building blocks for services.

Figure 2.15 visualizes the interaction of service archetypes and customer assets as they may be captured in the service catalog.

Figure 2.15 Classifying services using service archetypes and customer assets

Copyright © AXELOS Limited 2010. All rights reserved. Material is reproduced under license from AXELOS.

Services are based on service archetypes, such as lease, license, manage, operate, repair, audit, and design. In Figure 2.15, you can see these linked to the customer assets.

Mapping service archetypes and customer assets can also be useful to define strategies or to reveal patterns of demand or competence that have been built over time.

This is especially helpful for those service providers who were required to deliver whatever services the business demanded in the past without having a clear strategy. This is a common experience because organizations often grow organically rather than to a specific or strict strategy. This type of mapping will provide a baseline from which a service provider can identify future opportunities and services.

For example, the service provider may learn that many services are based on the same service archetype. They may learn that their resources and capabilities are mainly targeted at supporting business processes. This would be an asset-based service strategy—represented by the vertical arrow in Figure 2.16.

Figure 2.16 Asset-based and utility-based strategies

Copyright © AXELOS Limited 2010. All rights reserved. Material is reproduced under license from AXELOS.

Alternatively, the service provider may learn that what differentiates it is the ability to provide administrative services that support a wide range of customer assets. This is shown by the horizontal arrow in the diagram, which represents a utility-based strategy.

Most organizations have a combination of utility- and asset-based service patterns. Visualization of services helps them to understand where they are strongest and where they need to strengthen their portfolio, resources, or capabilities.

This combination of service archetypes and customer assets often results in a series of patterns that indicate the positions where the service provider is strong.

Services with closely matching patterns indicate that there is an opportunity for consolidation or perhaps packaging them as shared services.

If the applications asset type appears in many patterns, then service providers can focus more investments in capabilities and resources that support services related to applications. The same can be seen if many patterns include the support archetype. It can be taken as an indication that support has emerged as a core capability.

These are just simple examples of how the service catalog can be visualized as a collection of useful patterns. Service strategy can result in a particular collection of patterns, which is known as an intended strategy. A collection of patterns can make a particular service strategy attractive, and this is known as an emergent strategy.

Figure 2.17 shows examples of patterns of services as just described.

Figure 2.17 Visualization of services as value-creating patterns

Copyright © AXELOS Limited 2010. All rights reserved. Material is reproduced under license from AXELOS.

In this diagram, a single service may be constructed from one or more service archetypes and may support one or more customer assets, as follows:

- Service A is a utility-based communication service, which supports three types of customer assets: organization, processes, and knowledge.

- Service B is largely an asset-based process service, in which processes are supported by reporting, control, and support service archetypes. In this service, support services are also provided to support the organization asset.

- Service C is a support service archetype that supports financial assets, information, and applications.

- Service D is a range of service archetypes (administrative, reporting, control, and support) that support application assets. It also includes reporting support for infrastructure assets.

This visual method can be useful in communication and coordination between functions and processes of service management. The visualizations can be used as the basis of more formal definitions of services.

Proper matching of the value-creating context (customer assets) with the value-creating concept (service archetype) can avoid shortfalls in performance.

Questions of the following type can be useful:

- Do we have the capabilities to support workflow applications?

- What are the recurring patterns in processing application forms and requests?

- Do the patterns vary based on time of year or type of applicants or around specific events?

- Do we have adequate resources to support the patterns of business activity?

- Are there potential conflicts in fulfilling service level commitments? Are there opportunities for consolidation or shared resources?

- Are the applications and requests subject to regulatory compliance? Do we have knowledge and experience of regulatory compliance?

- Do we come in direct contact with the customers of the business? If yes, are there adequate controls to manage user interactions and information?

Step 5: Understand the Opportunities (Market Spaces)

Following the previous four steps, the service provider now has a good understanding of the customer and its assets. The service provider should now be able to map existing capabilities and resources to existing customer assets to understand what service it is able to provide.

Each customer has a number of requirements, and each service provider has a number of competencies. How does the service provider understand where its competencies will be able to meet the customer’s requirements? These interactions between the service provider’s competencies and the customer’s requirements are called market spaces. Market spaces identify the possible IT services that an IT service provider may wish to consider delivering.

In this way, a market space is defined by a set of business outcomes, which can be facilitated by a service. The opportunity to facilitate those outcomes defines a market space for a service provider.

The following are examples of business outcomes that can be the basis of one or more market spaces:

- Sales teams are productive with a sales management system on wireless computers.

- An e-commerce website is linked to the warehouse management system.

- Key business applications are monitored and secure.

Each of the outcomes is related to one or more categories of customer assets, such as people, infrastructure, information, accounts receivables, and purchase orders. These can then be linked to the services that make them possible. Each outcome can be met in multiple ways, but customers normally prefer those with lower costs and risks. Service providers need to use this information to ensure that they provide the services that are required by the customer and are profitable for themselves.

Step 6: Define Services Based on Outcomes

Defining services based on outcomes ensures that the customer’s requirements and value definitions drive the planning, delivery, and execution of the services. This means that not only does the customer receive the value it requires from the services, but that the service provider is able to capture value as well.

It is important to capture and understand value from the customer’s perspective. Customers may express dissatisfaction with a service provider even if the service targets are met if they do not fully understand the value the service is providing to their business outcomes. Defining a service based on customer outcomes ensures that this is less likely to happen.

Ensuring that the design is robust and that the operational requirements are delivered in the service will address both utility and warranty for the customer. This will allow the service provider to identify where improvements can be made.

Clarification of the service delivery will support the perception of the customer in determining the value of the service. It will also enable both the customer and service provider to more easily visualize any patterns to be found across service catalogs and portfolios. This will be useful in determining the coordination efforts required to deliver service. It will remove any ambiguity and avoids any misalignment with the customer requirements.

Figure 2.18 is one of two examples of outcome-based service definitions. The other is in Figure 2.19. In the diagrams, you can see that the service archetypes and specific customer assets from step 4 are used in these definitions.

Figure 2.18 Defining services with utility components

Copyright © AXELOS Limited 2010. All rights reserved. Material is reproduced under license from AXELOS.

Figure 2.19 Defining services with warranty components

Copyright © AXELOS Limited 2010. All rights reserved. Material is reproduced under license from AXELOS.

Figure 2.18 shows outcomes based on the utility of three different lines of service. In this case, the outcomes are expressed in terms of the outcomes achieved and the constraints removed (please note that utility can be achieved without having both outcomes achieved and constraints removed).

In the diagrams in Figures 2.18 and 2.19, you can see that the service archetypes and specific customer assets from step 4 are used in these definitions, which shows outcomes based on the warranty of the same three different lines of service.

Well-constructed definitions make it easier to visualize patterns across service catalogs and portfolios that earlier were hidden due to unstructured definitions. Patterns help to bring clarity to decisions across the service lifecycle.

Actionable service definitions are useful when they are broken down into discrete elements that can then be assigned to different groups. These groups will manage them in a coordinated manner to control and contribute to the overall effect of delivering value to customers.

Being able to define services in an actionable manner has advantages from a strategic perspective. It removes ambiguity from decision-making and avoids misalignment between what customers want and what service providers are capable of delivering. Without the context in which the customers use services, it is difficult to completely define value.

But it is possible to ask questions that assist with the definition of a service. Questions that can be helpful in defining the services in an actionable manner are listed in Table 2.2. These types of questions are crucial for an organization to consider in the implementation of a strategic approach to service management. They are applied by all types of service providers, internal and external.

Table 2.2 Defining actionable service components

| Service type | Utility (Part A and B) |

| What services do we provide? Who are our customers? |

What business outcomes do we support? How do they create value for the business’s customers? What constraints do our customers face? |

| Customer assets | Service assets |

| Which customer assets do we support? Who are the users of our services? |

What assets do we deploy to provide value? How do we deploy our assets? |

| Activity or task | Warranty |

| What type of activity do we support? How do we track performance? |

How do we create value for the business’s customers? What assurances do we provide? |

Step 7: Service Models

Service models can take many forms, from a simple logical chart showing the different components and their dependencies to a complex analytical model analyzing the dynamics of a service under different configurations and demand patterns.

Service models have a number of uses, especially in service portfolio management:

- Understanding what it will take to deliver a new service

- Identifying critical service components, customer assets, or service assets—and then ensuring that they are designed to cope with the required demand

- Illustrating how value is created

- Mapping the teams and assets that are involved in delivering a service, and ensuring that they understand their impact on the customer’s ability to achieve their business outcomes

- As a starting point for designing new services

- As an assessment tool for understanding the impact of changes to existing services

- As a means of identifying whether new services can be delivered using existing assets

- If not, then assessing what type of investment would be required to deliver the service

- Identifying the interface between technology, people, and processes required to develop and deliver the service.

Figure 2.20 provides an example of how the dynamics of a service can be represented in a service model.

Figure 2.20 Dynamics of a service model

Copyright © AXELOS Limited 2010. All rights reserved. Material is reproduced under license from AXELOS.

In this diagram, a retail service is illustrated. In this example, each component of the service is listed on a separate leg (or part), and the activities are numbered in the sequence in which the service is normally delivered.

Each component of the service is listed in relation to the other components, the dependencies identified, and the flows of communication and data indicated.

Step 8: Define Service Units and Packages

Services may be as simple as allowing a user to complete a single transaction, but most services are complex. They consist of a range of deliverables and functionality. If each individual aspect of these complex services were defined independently, the service provider would soon find it impossible to track and record all services.