Chapter Three. The Upper Right: The Value Quadrant

Breakthrough products are driven by a complex combination of value attributes that connect with people’s lifestyles. This chapter examines the seven attributes of value and introduces a Value Opportunity Analysis (VOA) process. During the last decade, the VOA has been one of the most widely adopted tools we have developed. The method helps interdisciplinary teams develop a shared understanding of the current state of a product opportunity and to project where value improvement needs to occur as they navigate the Fuzzy Front End. This is an essential step in any new product program. Failure to thoroughly and thoughtfully complete this phase will have a negative impact down the line. The goal is to create a baseline reference for determining directions for research and subsequent concept development; the result is an early definition of the requirements for product success.

The Sheer Cliff of Value: The Third Dimension

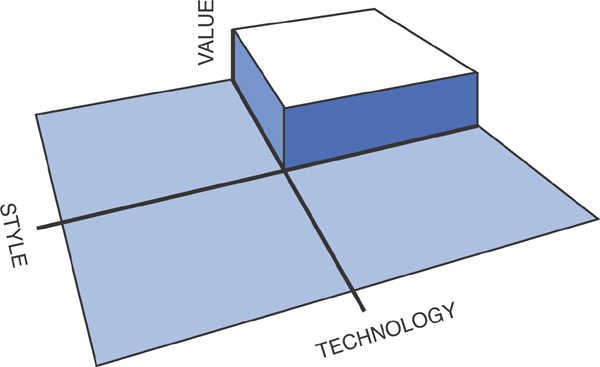

As you look through the Positioning Map diagrams shown in Chapter 2, “Moving to the Upper Right,” note how the Upper Right is separated from the rest of the quadrants. The reason is not just to highlight the importance of this quadrant. As mentioned in the previous chapter, the Upper Right has a third dimension, as shown in Figure 2.2 (repeated here as Figure 3.1). Unfortunately, it is not as simple as just putting a technologist and stylist together to move to the Upper Right. Products in the Upper Right are there because they add value to a user; we illustrate this in the 2-D version of the map by separating out the Upper Right quadrant. Adding value is not a trivial process—it requires a strategic commitment from the company to a user-centered iNPD (integrated new product development) process.

Figure 3.1. The three-dimensional Positioning Map showing the Upper Right Value quadrant.

Figure 3.1 illustrates our theory that the third dimension, value, comes into play only in the Upper Right. Chapter 2 showed that products in the other quadrants, especially the Upper Left and Lower Right, do provide some value by addressing either image or features. The Upper Right products, however, maximize image, features, and ergonomics, targeting a significant level of value that meets the needs, wants, and desires of consumers without sacrificing usefulness, usability, or desirability. Thus, products that fall in the other quadrants are on a different, lower level of value. The shift to the Upper Right is a dimensional change that is not gradual; it is abrupt and significant. In many ways, it represents a sheer cliff, which we call the Sheer Cliff of Value. Ascending this cliff requires a strategic approach that begins with commitment and planning and ends with a user-centered, integrated approach to product development. As discussed in Chapter 1, “What Drives New Product Development,” the product development process is akin to rock climbing. To create products in the Upper Right, you must climb the Sheer Cliff of Value.

In this chapter, we discuss customer-based value and show you how to use the concept of Value Opportunity to clarify a Product Opportunity Gap. Chapters 4, “The Core of a Successful Brand Strategy: Breakthrough Products and Services,” and 5, “A Comprehensive Approach to User-Centered, Integrated New Product Development,” then discuss the corporate strategy for committing to this process first by relating value to the corporate and product brand strategy and then by introducing a value-oriented product development process. The remainder of this chapter is devoted to understanding what value means in developing products for the Upper Right.

The Shift in the Concept of Value in Products and Services

During the period of mass marketing, value was seen as the services or features a product provided for the price it cost. Good value was based on the lowest cost with the greatest number of features. The goal was to keep cost low, make moderate profits, and sell in mass quantities. Products in the Lower Left are still driven by how many features can be delivered for the lowest cost. They are often sold in discount stores such as Walmart and Kmart. Value in its true sense, however, is lifestyle-driven, not cost-driven. According to Webster’s Dictionary,1 value is the relative worth, utility, or importance of one item versus another; the “degree of excellence”; or something “intrinsically valuable or desirable.” Relative worth does not mean cost, but rather the quality that causes something to be perceived as excellent. From the perspective of a product, the key terms are utility (namely, usefulness and usability), desirability, and overall perceived excellence. A product is considered excellent when it is ranked high in all appropriate aspects of value and delivers the qualities people are looking for. For the purpose of the development of Upper Right products, we define value as the level of effect that people personally expect from products and services, represented through lifestyle impact, enabling features, and ergonomics—together, these result in a useful, usable, and desirable product.

So a product is valuable if it is useful, usable, and desirable. Though not directly recognized as a definition of value, these words were first applied to product development by Fitch, a design consulting firm headquartered in Columbus, Ohio, to describe aspects of a successful product. A useful product is one that satisfies a human need, is capable of being produced at reasonable cost, and has a clear market. A usable product is one that is easy to operate, easy to learn how to operate, and reliable. Finally, a desirable product is one whose technology, function, appearance, and market positioning make customers want to own it. Products in the Upper Right are useful, usable, and desirable—that is, they have high value in that they are perceived as excellent in a number of factors.

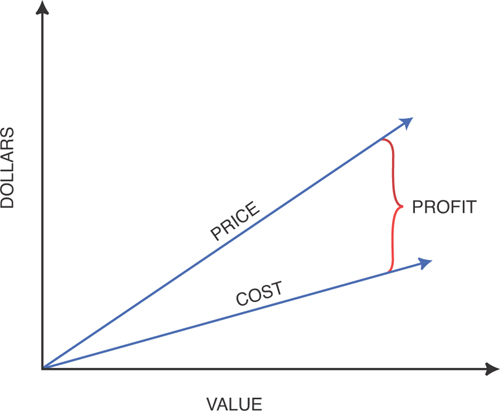

Although cost is still an issue in the era of market segmentation, the more powerful factor is the consumer’s need to connect product purchases with personal values. When a product does connect, customers are willing to pay a higher price. People purchase products that enrich their experiences based on what is important to them—their values. The product must support that value base. The more the product does support that base—in other words, the higher its perceived value—the more people will pay for it. In the ideal case, and cases we have observed in practice, the cost to make a highly valued product increases less rapidly than the amount people will pay for it! In other words (as shown in Figure 3.2), the more value in a product, the higher the price people are willing to pay, with the price increasing more rapidly than the cost. The profit is the price minus the cost; thus, the profit increases with higher value. The OXO GoodGrips peeler adds so much value that consumers will pay several times that of the generic metal peeler. However, the cost to produce it is not several times that of the generic counterpart, so the profit margin is significantly higher for the higher-valued product. This is also the case in the auto industry with higher-end vehicles built on the same platform. Although an SUV costs twice the price of a pickup truck whose platform it is built on, the cost to produce the SUV is not double that of the truck. The auto companies make significant profit on these high-value vehicles. This is the first way Upper Right products lead to increased profit.

Figure 3.2. Price and Cost versus Value—Profit increases with added Value.

In some instances, due to manufacturing costs and the expenditure for emerging technologies, high-value products may have a sales price that demands a lower profit margin compared to the cheap, poor-quality, competitor’s product. But although proportionally they make less profit per item, they still make a large profit based on their increased volume of sales. This is the second way Upper Right products lead to increased profit. The Lower Left competitor or off-the-map rip-off created by looking for the cheapest way to manufacture usually results in a poor-quality product that may be churned out for a fraction of the Upper Right cost but that customers do not value and will never pay a premium for.

The third way that Upper Right products lead to increased profit is by establishing brand—and, thus, customer—loyalty. Although not all Upper Right products result in higher profit per item over competitors in the other quadrants, producing an Upper Right product is sometimes a strategic decision. This decision is made to establish a long-term relationship with the customer. When an Upper Right product fulfills the expectations of customers, they are more likely to return to the brand for future purchases. As discussed in detail in Chapter 4, this happens because the product is the core of a company’s brand strategy, and the value of the Upper Right products help to establish strong brand equity. Strong brand equity means that customers are more likely to purchase your product over one from a competitor that has not established a core or appropriate brand identity. Not only will customers return to purchase the next generation of the product they enjoyed, but when they eventually seek out new products or higher-value products, they will return to the company with that Upper Right product.

This was the strategy Volkswagen used in 1998 when it redesigned its classic design and introduced the new Beetle. The features and style of the product met and generally surpassed the value expectation of the customer. Although VW did not charge an exorbitant amount for the vehicle, the goal was to move customers into higher-priced lines, such as the Passat, with future purchases. Sometimes brand can be built with an Upper Right product that not everyone can afford. Navistar introduced the LoneStar, discussed in Chapter 9, “Case Studies: The Power of the Upper Right,” as a means to rejuvenate its brand and change the perception of its trucks as innovative and cutting edge rather than mundane and basic.

The fourth way an Upper Right product leads to increased profits is actually by charging less than the competition. An effective process of integrating engineering and design can lead to products with fewer parts and a more efficient process of manufacturing and using finishes. These products end up costing less to produce than the previous solutions. Sharing that cost reduction with the consumer makes a strong statement for enabling market penetration. It also establishes a strong brand equity built on innovation and cost reduction. Although this enviable position is not easy to come by, the attention to detail that results from creating an Upper Right product can have surprising ramifications. Dell Computer developed a system for innovation in product customization and delivery that enabled it to acquire a strong share of the market yet keep its products at competitive prices. Unfortunately, it also contributed to the commoditization of the PC and, thus, its own business.

You might think that adding new technological features is a way to attract customers and increase sales price and, hopefully, profit. But this works only if customers value and desire the feature. Just having a feature attracts only a limited group of early adopters. If the broader majority of customers don’t want the feature, they won’t buy it. Even so, there is a limit to what an early adopter will pay just to have the technology. But there is no limit to innovation and the potential value it can deliver to a customer. If you create features that people value, need, and desire, they will pay for that feature. And that is a property of a product in the Upper Right.

Qualities and a Customer’s Value System: Cost Versus Value

Consumers have come to expect a high degree of quality in the products they buy. Quality tools and programs such as TQM, QFD, 6σ, and ISO 9000 have continued to raise the bar on the quality of manufacture and product performance. These attributes have become the expected baseline of entry into a market. What makes a product successful in the marketplace today, however, is determined by the qualities it represents and how these product qualities connect to personal values. Product qualities result from the combination of image, features, and ergonomics.

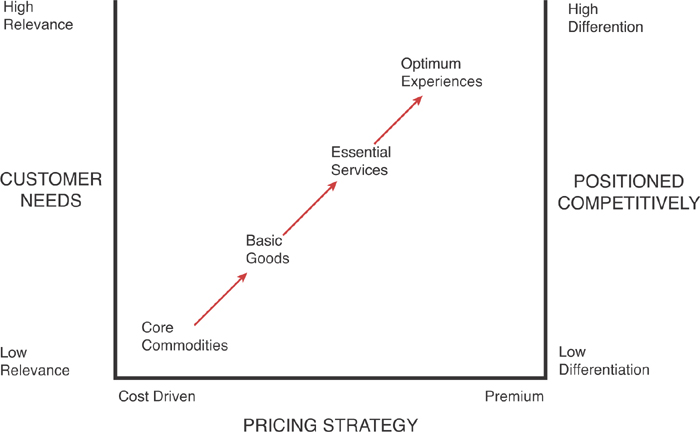

B. Joseph Pine and James Gilmore describe the emerging economy as the “experience economy,” in which companies will succeed by producing or supporting experiences.2 According to Pine and Gilmore, commodities lead to goods, which, in turn, lead to services that are now leading to experiences. These experiences are a new source of value for the consumer. What is striking in their research is that each progression has led to higher pricing of the product (see Figure 3.3). Commodities provide the means to create goods that provide services that, together with goods, stage experiences. There is as much as an order of magnitude increase in price between goods and services and experiences. In other words, people will pay—and pay highly—for quality experiences. Figure 3.3 also shows how those companies that provide experiences differentiate themselves from the competition.

Figure 3.3. The progression of economic value from core commodities to optimum experiences.

(Adapted from The Experience Economy, by Pine and Gilmore2)

As stated earlier, form no longer follows function. This has been replaced by form and function fulfilling fantasy. The shift from the industrial revolution to the Information Age is also the shift from the world of high work effort with low fantasy expectations to the world of work as a means to provide for an ever-increasing array of fantasy expectations. Customers expect a product to enhance and fulfill their lifestyle, both physically and symbolically. In short, people want to fulfill their dreams. But what one group fantasizes about as an ideal product is different than what another group imagines.

The entertainment industry has created a world culture of fantasy. Movies, television, books, vacations, and products are all attempts to live up to customer dream expectations. Vacation resorts such as Las Vegas and Disney World or cruises to natural settings bring fantasy into experience. People all over the world want to experience that level of fantasy. They want to extend that fantasy into every phase of their lives. Think about the influence of Star Wars, The Matrix, and Star Trek on products, fashion, and digital imaging. We now have products that look like three-dimensional cartoons (such as Graves products for Target) and cartoons that look real (such as the toys in Toy Story, with the Buzz Lightyear action figure toy created from the same type of digital representation used to create the cartoon character in the movie). As anticipated by Star Trek, we can watch videos while on the move, talk to anyone anywhere in the world, and use onboard navigation systems to figure out where we are on the planet at any moment in time and determine where to go next to arrive at our destination. As predicted in Minority Report, we can even use our hands to move items around a screen and immerse ourselves in a virtual world with Microsoft’s Kinect, even if, for now, it is only to play a game.

But it isn’t just fantasy for a personal lifestyle. People expect fantasy in the business-to-business world as well. Consider utility connectors for commercial appliances that provide the feeling of confidence and, for the commercial kitchen designer, make you feel on top of your game. Or consider the dangerous, dirty, and dull task of inspecting sewer systems; the fantasy here is to not have to be in or around the sewer. RedZone Robotics fulfills that fantasy to crews that used to have to go down to inspect deep sewers by having a robot do the task instead.

In the Upper Right are products that differentiate themselves from the competition by enhancing experiences. In other words, the Upper Right represents the products that support the new experience economy.

As consumers become more sophisticated in their ability to select products and their fantasy expectation increases, companies must learn to understand the new value structure of their core customers. Though aspects of this value system are deeply rooted in religious and personal beliefs, much of the system changes rapidly as people mature. Culture and trends shift faster and faster in more and more product markets. Thus, successful companies must see the process as dynamic and must constantly update their understanding of who their customer is. Connecting product qualities to the value system of customers is the new method for creating successful products.

Arguing for value-driven products over cost-driven products does not mean that price is never an issue. Pine and Gilmore state, “[N]o one repealed the laws of supply and demand. Companies that fail to provide consistently engaging experiences, overprice their experiences relative to the value received, or overbuild their capacity to stage them will of course see demand and/or pricing pressure.”3 People have a capacity that limits what they can afford. In the down economy after the fall of Lehman Brothers, what people valued and where they spent their money shifted. Yet those products that people did value—such as the iPhone and iPad, the $4 Starbucks grande latte, and the LoneStar truck—still demanded a premium in price and profit. The point is that people will pay for value beyond what they pay for commodities, even in a down economy. The key is to understand what that limit is and what a given market looks for in a product, and then to add the right features for the appropriate value.

We call this psycheconometrics. Psycheconometrics is the psychological spending profile of a niche market. It determines what people perceive is worth spending money on. The user experience is enhanced by the value people feel they are paying for.

Clearly, Starbucks provides a richer experience than the local diner, OXO GoodGrips boosts the cooking experience beyond the generic peeler, and the FIT System provides personal health feedback beyond the pedometer. People have paid a significant cost increase for the added value of these experiences. It has been argued that if two identical products are on the market, the one that costs less will succeed. We respond that, in practice, no two identical value-oriented products are on the market. Two different companies or divisions create differences in the products through brand equity, if not through differing features. Why do people shop at Tiffany’s when they can buy similar jewelry at a lesser price in the local jewelry store? The answer is that Tiffany’s provides a shopping experience and a story for the customer to tell. The Tiffany’s experience helps people feel better about themselves, and people are willing to pay for that.

However, if you are going to charge more than the competition, the customer had better perceive that the added value is worth the additional cost. If the product does not add value, then as a higher-cost commodity, it will fail. Manufacturing commodities is still an option, but you must recognize then that you are creating Lower Left products and that price becomes the purchasing driver.

Value Opportunities

Value can be broken down into specific attributes that contribute to a product’s usefulness, usability, and desirability and that connect a product’s features to that value. Products enable an experience for the user, so the better the experience, the greater the value of the product to the consumer. Ideally, the product fulfills a fantasy by facilitating a more enjoyable way of doing something. We have identified a set of opportunities to add value to a product, called Value Opportunities (VOs). These seven VO classes—emotion, aesthetics, identity, ergonomics, impact, core technology, and quality—each contribute to the overall experience of the product and relate to the value characteristics of useful, usable, and desirable.

The VOs differentiate a product from the competition in the way that people’s needs, wants, and desires influence the purchase and use of that product. The VO is a snapshot in time. What makes one set of VOs relevant today, due to the current analysis of SET Factors, might make the same VOs irrelevant tomorrow. Also, interpreting the VOs is based on the SET Factors for a target market; the attributes one group finds important might be uninteresting to another.

The ergonomics, core technology, and quality VOs each address the satisfaction of the product during use, both immediately and over the long term. The social and environmental impact, product identity, and aesthetics VOs each address lifestyle aspects of the consumer. The emotion VO connects most directly with the consumer’s fantasy in using the product. Together these VOs define the third axis of the Upper Right, the value of the product to the consumer. In examining each of these in more detail, recognize that each affects a product differently. Although each is broken down into specific VO attributes, this breakdown can be augmented as needed; as cultural needs change, new value needs will emerge. This list, however, is fundamental and generally supports the analysis of value for most product classes, including all of the products discussed in this book. Since the first edition of this book, the VOs have been used to design and analyze hundreds of products in a variety of applications. In each case, these value attributes have directly applied, with no need for further augmentation. The key is to define these attributes in the context of the product domain, enabling a tuned and focused value proposition.

The VOs are an extension of the breakdown of value in Chapter 2 as lifestyle impact, features, and ergonomics. Lifestyle impact represents the emotion, aesthetics, identity, and social impact value opportunities; features represent the core technology, quality, and environmental impact VOs. In the last chapter, we argued that only Upper Right products are strong in all three categories. Although all VOs might not be targeted by an Upper Right product, generally at least one relevant VO attribute that falls under each category must be targeted for a product to exist in the Upper Right. Of course, the more VO attributes that are targeted and maximized, the stronger the product’s place in the Upper Right will be.

Emotion

The first Value Opportunity is emotion. All the VOs support the product’s capability to contribute to the user’s experience, but emotion defines the essence of the experience; the emotion contribution defines that fantasy aspect of the product. If the VOs were a hierarchy, the emotion VO would be at the top, ultimately supported by the other VOs. In their book Built to Love,4 Boatwright and Cagan demonstrate the value of emotion in increased willingness to pay and overall corporate profits. The emotion VO is the perceptual experience of the consumer when using the product. Different fantasies distinguish different products. We break the attributes of emotion into these categories:

• Sense of adventure—The product promotes excitement and exploration.

• Feel of independence—The product provides a sense of freedom from constraints.

• Sense of security—The product provides a feeling of safety and stability.

• Sensuality—The product provides a luxurious experience.

• Confidence—The product supports the user’s self-assurance and promotes motivation to use the product.

• Power—The product promotes authority, control, and a feeling of supremacy.

Think about the sensual feeling of sipping a cup of coffee at a Starbucks in Manhattan on a cool fall day. Consider the feeling of adventure, security, and calm in a child having an MRI in the GE Adventure Series. Think about the sense of adventure, independence, and confidence that results from positive feedback about a more active lifestyle while wearing the BodyMedia FIT arm band. Products can utilize more than one emotional attribute toward value. This is true for each VO.

Although some products succeed by focusing on key attributes, the more relevant attributes of each VO that can be targeted, the higher the likelihood that a product will add value to a target market. Each Upper Right product captures a range of VO attributes, as shown later in this chapter and in Chapters 8–11.

Aesthetics

Aesthetics, the second Value Opportunity, focuses on sensory perception. The five senses are all important attributes of this VO. Many products focus only on visual and tactile senses. However, stimulating as many senses as possible through the use of a product or environment builds a positive association of the product with its application. This provides an exciting opportunity to add value to a product if competitors’ products lack this focus. Although aesthetics are expected in consumer products, their opportunity to differentiate business-to-business products is often overlooked. The range of senses involved with aesthetics supports the emotion value opportunity, especially the sensuality attribute. The aesthetic attributes are:

• Visual—The visual form must relate shape, color, and texture to the context of the product and the target market.

• Tactile—The physical interaction of the product, not only focusing on the hand, but also including any other physical contact between the product and user, must enhance the product experience.

• Auditory—The product must emit only the appropriate sounds and eliminate undesired sounds.

• Olfactory—The product must have an agreeable smell, providing appropriate aromas and eliminating undesirable odors.

• Gustatory—Products that are designed to be eaten, used as a utensil, or otherwise placed in the mouth (such as a child’s toy) must have an optimum flavor or no flavor at all.

Stimulating as many senses as possible through the use of a product builds a positive association between the user and the use of the product.

Product Identity

Products in the Upper Right make a statement about individuality and personality, expressing uniqueness, timeliness of style, and appropriateness in their environment. The product identity VO captures differentiation of the product in look or performance from the competition, connects the product to (or, at times, defines) the brand identity (see Chapter 4), and gives the product context in the marketplace. The identity of the product supports the emotion VOs and the consumer’s fantasy in owning and using the product. Three attributes of product identity are personality, point in time, and sense of place:

• Personality—The product has unique characteristics in look and performance that set it apart from the competition. The two main issues in a product personality are 1) the ability of a product to communicate its core capabilities and differentiate itself from its direct competition, and 2) the connection that a product has to the rest of the products produced by that company.

• Point in time—For a product to succeed, it has to capture a point in time and express it in a clear, powerful way. Point in time is a combination of features and aesthetics that define the reference to a time period and the emotions that result from that period, whether future or past, and potentially defining a new aesthetic trend. This is captured by the dynamics of the SET Factors indicating changes over time.

• Sense of place—Products must be designed to fit into the context of use. This is also a by-product of the SET Factors, providing the appropriate look and feel for the product when and where in use by the customer, and when offered for sale in the marketplace.

Consider the design of the Frozen Concoction Maker. Its unique form features, bright color accents on the pitcher against a soft gray background with shiny trim, define a fun but serious personality that implies confidence that it can handle any party. The product references a contemporary point in time, highlighting the technology advantages over competitive products. The Frozen Concoction Maker has a sense of place that connects Key West to the backyard, providing a focal point for a party, especially while playing Jimmy Buffett’s Margaritaville.

Impact

A company has a number of ways to demonstrate that it can be a responsible manufacturer and respond to socially oriented issues. Social responsibility is connected with the customer’s personal value system and, as discussed in Chapter 4, can often build brand loyalty. Charitable donations, safe work environments, and health- and family-oriented benefits all promote the corporate image. However, the company can positively affect society through the product itself. Based on consumers’ preference to buy products that benefit rather than hurt the environment or social groups, opportunities exist to add value to a product through social and environmental impact. Products can also have social impact by affecting changes in how people communicate and interact with each other.

• Social—A product can have a variety of effects on the lifestyle of a target group, from improving the social well-being of the group to creating a new social setting (see the accompanying sidebar).

• Environmental—The effect of products on the environment has become an important issue in terms of consumer value. Design for the environment, or “green design,” focuses on minimizing negative effects or producing positive effects on the environment due to manufacturing, resource use of the product during operation, and recycling (see the accompanying sidebar).

In 2001, when the first edition of this book was released, this Value Opportunity and its related social and environmental attributes were probably the least explored of all the VOs. At the time, it was hard to get companies to even think about sustainability, never mind design products to minimize environmental impact. Today sustainability is becoming a core value to consumers. Similarly, attention to social well-being was not a focal point. In the past decade, social media was invented, with Facebook, Myspace, and other Web sites changing expectations for social interactions and sparking technology features on computers and smartphones that now enable constant communication. In addition, in terms of the aging population, Baby Boomers have changed the social expectation, and products are emerging to enable social interaction as people age in place. Social expectations and their delivery will continue to evolve and influence the design of products in consumer and business-to-business markets. Thus, the impact VO continues to have a growing effect on product development.

Ergonomics

The next Value Opportunity focuses on usability. Ergonomics refers to the dynamic movement of people and their interaction with both static and dynamic man-made products and environments. The terms ergonomics, human factors, and interaction are all related and are discussed in Chapters 7, “Understanding the User’s Needs, Wants, and Desires,” and 8, “Service Innovation: Breakthrough Innovation on the Product-Service Ecosystem Continuum.” Ergonomics has both a short-term and long-term effect on the perception of a product. Consumers look for comfortable fit, maneuverability, and intuitively simple controls in a new product, but a product must also hold up over time in comfort, consistency, and flexibility in use. The ability of a person to interact with a product with ease, safety, and comfort contributes greatly to its overall value. These three attributes of ergonomics are also the attributes of the VO:

• Ease of use—A product must be easy to use from both a physical and cognitive perspective. A product should function within the natural motion of the human body. The ergonomics of the size and shape of components that a person interacts with should be logically organized and easy to identify, reach, grasp, manipulate, and navigate.

• Safety—A product must be safe to use. Moving parts should be covered, sharp corners eliminated, and internal components shielded from users. Application scenarios should be considered to anticipate and mitigate unsafe uses of a product.

• Comfort—Along with ease of use and safety, a product should be comfortable to use and should not create undue physical or mental stress during use.

Other products might not target social conscientiousness directly, but they still affect the interactions among people. Starbucks created a nonalcoholic way for people to meet and enjoy each other’s company in a public setting. On the other hand the Frozen Concoction Maker created a primarily alcoholic way for people at parties to enjoy a hot summer’s evening. The FIT System enables people to blog with each other, encourage others, and offer contests about healthy lifestyles.

Even Harley-Davidson created an entire new subculture of social interaction. The Harley was once associated with a criminal fringe lifestyle, but the company refocused its brand and extended its product line. Today white-collar workers escape the 9–9, Monday–Friday grind and transform themselves on weekends by joining Harley Clubs that ride in full Harley attire. The Harley motorcycle—the core product—and all of its accessories create an environment that fosters a sense of camaraderie and escapism. (See the case study in Chapter 4.)

Core Technology

Just as aesthetics and personality target the style aspects of the Positioning Map, the core technology and quality Value Opportunities target the technology aspects. Technology alone is not enough, but technology is essential. It must enable a product to function properly and perform according to expectations, and it must work consistently and reliably. People might want more than just technology, but they expect technologies to evolve at a high rate with a constant increase in functions that are better and more consistent.

• Enabling—Core technology must be appropriately advanced to provide sufficient features. Core technology can be emerging high technology or well-manufactured traditional technology, as long as it meets customer expectations in performance.

• Reliable—Consumers expect technology in products to work consistently and at a high level of performance over time.

Products should be perceived to be of high quality when purchased and should meet those expectations over a long period of time.

Quality

The final Value Opportunity is quality: the precision and accuracy of producing a product. For physical products, this includes manufacturing methods, material composition, and methods of attachment. For services, interaction, and software, this includes the consistency of interaction across a product and the flexibility of a product in use scenarios. Although related to technology, the focus here is on the production of the product itself and the expectation that customers have for product quality. Products should be perceived to be of high quality when purchased and should meet that expectation over a long period of time. This value is measured by the sound a door of a car makes, the seams connecting two parts of the laptop computer, or the seamless flow of a package from pickup to delivery, for example. Although not an easy task, manufacturing technologies and assembly methods have progressed to the point that this goal is both obtainable and expected. A major argument of this book is that, by spending the time up front to create a product that meets customer expectations, the downstream production detailing and delivery becomes more straightforward. By including manufacturing in discussions early in the process, potentially costly defects can be caught and dealt with early before economic investments in molds and assembly. Likewise, the inability to deliver the expected features in a service is addressed before the service is made available. The quality VO is broken down into two attributes:

• Craftsmanship (fit and finish)—The product should be made with sufficient tolerances to meet performance expectations.

• Durability (performance over time)—The craftsmanship must hold up over the expected life of the product.

As discussed in Chapter 8, the quality VO attributes of craftsmanship and durability are equally applicable for physical product, services, interaction design, and software. However, in the nonphysical fields, the terms consistency for craftsmanship and flexibility for durability are often used and might make more sense for companies in those fields.

Value Opportunity Charts and Analysis

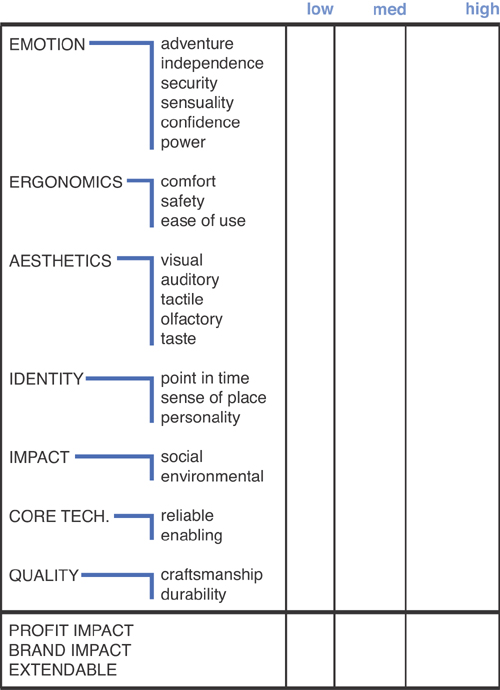

The Value Opportunities provide the basis to determine what characteristics a new product must have to successfully move to the Upper Right and also to analyze why successful products exist in that quadrant. The goal is to assess the VO attributes of existing or competitor products and to create target VOs for a new product. Figure 3.4 shows a Value Opportunity chart that lists each VO class and its attributes in a column. The values are measured in a qualitative range and are expressed as low, medium, and high for each attribute. If a product did not meet any level of that attribute, no line is drawn. The assumption is that if there was any intent to focus on an attribute, there would be at least a low measure of success; if not, the blank line indicates failure. If an attribute is not relevant to a product opportunity the term “N.A.” (for “not applicable”) is used.

Figure 3.4. Value Opportunity chart.

Below the chart are listed profit impact (across the company), brand impact (on company brand), and extendable. Although these are not VOs, they are included in the chart because they indicate the overall success of the product. A product in the Upper Right produces profit in a number of ways. The argument is that products might cost more, but people will pay for value. Companies can increase market share and gain stockholder and investor confidence. They can generate greater sales than other products in the company or significantly add to the existing product lines. They can increase the equity of a brand and/or broaden the equity by moving into new desirable markets. Companies such as Mercedes have always enjoyed greater profit margins. Sam Farber, founder of OXO, has stated that one of the major challenges a company has to meet is to determine the potential overall profit of a product that will cost more to produce and will need to be priced higher than the competition. Making this decision requires the combined insight of the team and management, along with appropriate feedback from customers. It has been said that only one company can be the cheapest; the rest have to compete using design. We add that they must compete using integrated design that produces value.

One question often asked is “Doesn’t cost play a major role?” Yes, it does. However, the goal is to focus on what customers value—what they need, want, and desire—and then make decisions based on cost and the willingness of the market to pay for the resulting product. Costs can be trimmed as long as they do not change the ability of the product to deliver on the VO attributes. If a product delivers value that people need, want, and desire, they will pay for it. Smart design does not have to result in high costs. But if costs are higher than customers will pay, instead of trimming value, the product should be reassessed and possibly not produced at all; a new means to deliver the VOs should be explored.

People we have interviewed from various industries note that companies often make a “safe” decision and let spreadsheets and cost reduction become the primary ways to increase profit. Although these approaches are sound, they can actually backfire and have a short-term payoff with a long-term negative effect. As price stays the same and profit is generated through reduction in parts, cost, labor, and steps in manufacturing, companies can start to lose the ability to be innovative. They lose sight of the competition and emerging trends. Companies have to learn to balance innovation risk management with conservatively tested measures of cost controls, carryover, and parts reduction. Developing a new product without significant innovation is a bigger long-term gamble than investing in an innovative product that brings new product attributes to the marketplace. Creating a stable platform and then using mass customization to create the proper style and feature interface is one method of accomplishing this. Swatch Watch, Nokia, VW, and Apple (via the apps store) have been successful with this approach. Establishing a consistent approach to product development and then applying it creatively in different products is another. OXO and Tupperware have successfully developed new products with this technique.

A strong product and corporate brand means a higher likelihood of repeat business to the company and a higher price that the product commands.

Having maximized their Value Opportunities, products in the Upper Right have a strong brand identity and can have an even greater impact on the corporate brand. As stated earlier and discussed in more detail in Chapter 4, although many important factors form the brand strategy of a company, the product or service must be core to the process. Upper Right products and services have a strong brand impact at the corporate level, while products in the other quadrants tend to either be nondescript (Lower Left quadrant) or have heavily biased brand impact from aesthetics (Upper Left quadrant) or technology (Lower Right quadrant). A strong product and corporate brand means a higher likelihood of repeat business to the company and a higher price that the product commands.

Products in the Upper Right often lead to expansions into other versions of the same product or other product lines. GoodGrips now makes more than 850 products, including pizza cutters, knives, and gardening tools. Starbucks has expanded in a number of store locations and also in environments where their coffee is sold and with product types (such as ice cream) that focus on coffee. The Margaritaville Frozen Concoction Maker comes in several different models with different capabilities and other related products. Lack of extendibility will not prevent a product from moving to the Upper Right, but the VO attributes are generally so strong that such extensions are natural.

The VO chart of a successful product is useful in trying to understand what VO attributes the product team targeted and how well the product turned out. However, the chart is most useful as a comparison against competitive products and as a means to determine what attributes a new product must have to be differentiating and successful, and possibly revolutionary. In the Value Opportunity Analysis (VOA), one chart indicates a previous product or solution to a task; the other represents the product of focus. In many ways, this analysis is easier than when considering a product alone. When focusing on the target market, understanding how previous products failed enables you to discover how much better your product is—or should be.

We now apply a VOA to the Frozen Concoction Maker, FIT System, Starbucks, and Adventure Series MRI.

When focusing on the target market, understanding how previous products failed enables you to discover how much better your product is—or should be.

VOA of Margaritaville Frozen Concoction Maker

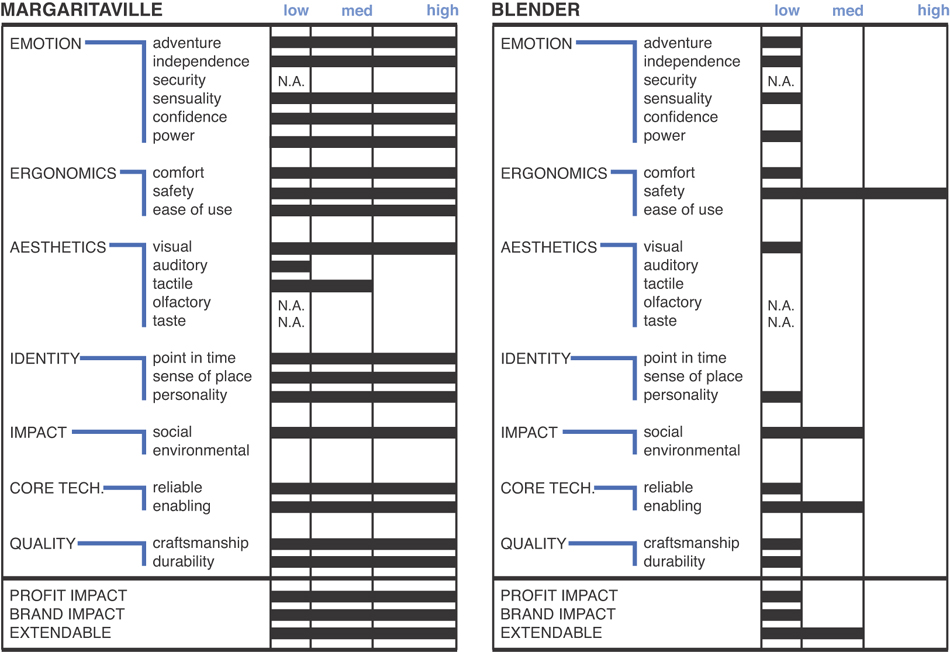

Comparing the VOA of a typical blender with the Margaritaville Frozen Concoction Maker reveals why this device has become an instant hit in the market. The Frozen Concoction Maker evokes a sense of secured adventure; users can experiment with different ingredients, but they are assured that the maker will deliver their frozen drink in the best thickness and ice consistency. In typical blenders, on the other hand, the results are unpredictable. Often ice is not thoroughly crushed and the frozen drink is mixed with large chunks of ice, or the ice is overly crushed and results in a watery drink. The back reservoir of the Frozen Concoction Maker prevents the melted ice from seeping into the drink and making it watery. The Frozen Concoction Maker aesthetic has given it a specific personality, which is clearly related to the Margaritaville brand and its cool culture of enjoying the moment and having fun. After the success of the original maker, the company has expanded its line to new models. It currently offers a cordless maker that can be carried to any destination, as well as a mixed drink maker that is capable of making 48 different types of drinks at once, further empowering the user to be in control of the party. The Frozen Concoction Maker encourages social interaction and, similar to the water cooler in the office, can be the central place to congregate.

The Margaritaville Frozen Concoction Maker is about aesthetics, ergonomics, and functionality, resulting in an enjoyable experience for users. The result of the unique combination of aesthetic and ergonomic value has a strong, fun identity. It utilizes high technology in an invisible manner and enables the user to easily interact with the blender and intuitively operate it without going through the manuals, and with safety in mind. It’s easy to interact with. Although tall in comparison to other kitchen appliances, the product fits comfortably in an outdoor environment. Its operational noise is also lost in the outdoor party. The blender, on the other hand, lacks personality, aesthetic, emotional reward, and social interactions. It’s no wonder almost all users claim that the high price is justified by the Frozen Concoction Maker’s quality and the great frozen drinks it makes.

Figure 3.5. Value Opportunity Analysis of Frozen Concoction Maker versus blender.

VOA of BodyMedia FIT System

Two competitive VOAs can be compared to the BodyMedia FIT System. The first is the clinical VOA that includes both the sleep lab and the metabolic cart, which, as Figure 3.6a shows, is quite sparse. In a clinical product without regard to the Upper Right, little positive emotion is designed into the product. The environment is neither comfortable nor easy to use: The patient needs to wear leads and sleep in a lab or has a tube in the mouth to breathe into. Aesthetics are also bland. The core technology, however, is its strength, enabling and providing reliable results. The technology itself is durable, although parts are disposable. There is no brand recognition, yet the product does enable a profit based on the charges to stay in a sleep lab or use the metabolic cart.

Figure 3.6b shows the pedometer as the consumer competitor. Here the VOA shows more attention to the value proposition than the clinical lab. Some emotions result from the capability to take a level of control over one’s health and be able to explore the environment while walking or running. Pedometers are extremely easy to use and comfortable. Aesthetics become more important, with a range of visual and tactile aesthetics in different models. They clearly belong in the equipment of those who are exercising but are generally indistinguishable. Although people often like to exercise with others, pedometers neither encourage nor discourage such interaction. They have basic technology that delivers useful information, but at the time that BodyMedia was developing the BodyMedia FIT System, pedometer technology was quite basic, using a mechanical lever mechanism. Most pedometers are basic in their overall quality (although some are built well). Finally, the prices and the costs are both low so that a decent profit can be made.

Contrast this with the VOA for the BodyMedia FIT System (see Figure 3.6c); note that the VOA for both the clinical and consumer products is the same at the chart level, although product requirements might differ slightly. The product pays attention to all aspects of the value proposition that customers seek. The product enables an emotional connection. People can go anywhere they want and track their performance. A sense of luxury accompanies using the FIT that enables a feeling of confidence and power in people who take control of their health. From an ergonomics perspective, the product is comfortable to use; that comfort has increased over multiple iterations of the product so that today it is very comfortable—people almost forget they are wearing it. Most important, the FIT is extremely easy to use. It also looks great, with a contemporary aesthetic and brand recognition that fits into people’s daily lifestyle and that makes people proud to wear it. Unlike the previous competitors, the FIT enables communities of people that connect to discuss their health and healthy lifestyle; some present their achievements in their blogs, and others offer competitions to see who can burn the most calories. However, the product cannot yet be designed with sustainability in mind. BodyMedia paid attention to the technology and manufacturing qualities, making a product that is effective, well made, and durable (it can even get wet briefly).

Figure 3.6. Value Opportunity Analysis of BodyMedia products versus clinical sleep lab and metabolic cart and consumer pedometer.

The BodyMedia FIT System has a strong differentiating brand, with strong profit impact that includes a “razor blades” model of recurring revenue based on its service. The product platform has demonstrated its extendibility, progressing from the clinical to consumer markets. APIs allow for integration into a range of systems; for example, you can watch your Panasonic TV and see your caloric burn rate on the screen.

Although two somewhat different products were used for the clinical and consumer markets, the VOAs for both are quite similar. The consumer version includes the service component, potentially amplifying some of the VO attributes. And some aspects of the product, such as its size, have only made the overall experience better.

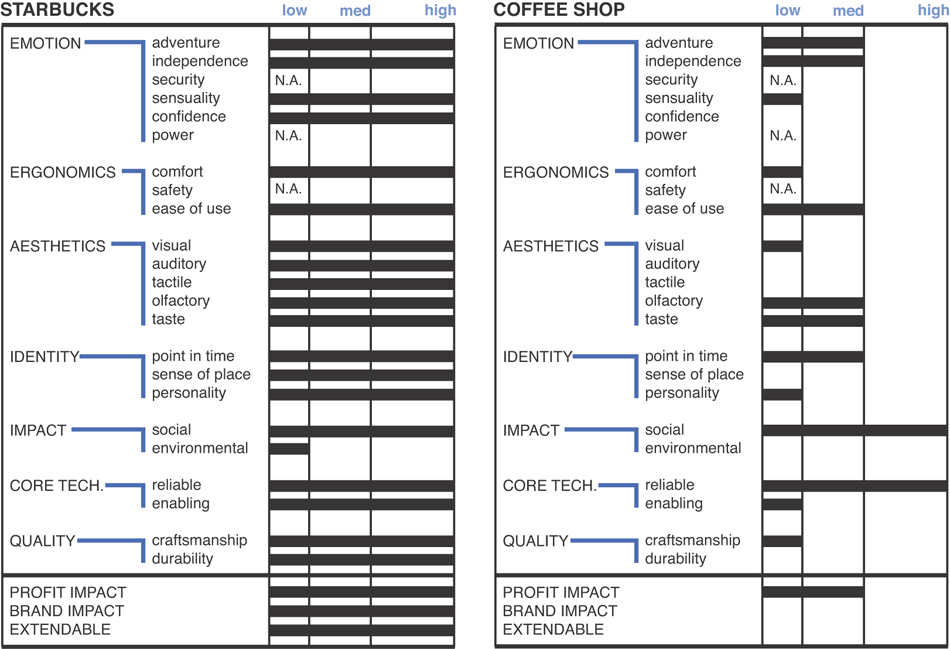

VOA of Starbucks

We now turn to a Value Opportunity Analysis of Starbucks (see Figure 3.7). Recall the SET Factors in Seattle and the target market of professionals with disposable income. The previous focal points for coffee and conversation were coffee shops (our choice of comparison), diners, and doughnut shops. The typical coffee shop had reasonably tasty and reliable food and a pleasant but often dated and nondescript atmosphere. Patrons gathered to socialize and eat, but they didn’t consider it a leisurely environment, a particularly inviting space, or the place to “be seen.” Instead, there was a level of independence with a focus on food and often a sense of adventure to find the really distinct environment with the great specialties instead of the usual mediocre fare. Coffee shops are reasonably profitable but typically lack any brand equity or ability to expand.

Figure 3.7. Value Opportunity Analysis of Starbucks versus a coffee shop.

Diners and coffee shops are as American as the apple pie they serve. However, as the SET trends shifted, the environment, atmosphere, and perceived quality of food and coffee diminished. Diners gave way to fast food chains that created increased speed and established a threshold of consistent value at low prices. As the cycle continued, fast food lost its perceived value and an opportunity arose for Starbucks to create a new solution that promoted coffee first and food second. Its standard was higher, and so was the price. The environment changed to create an appropriate atmosphere for purchasing and experiencing a higher-quality coffee than could be purchased at a fast food chain or at the few remaining diners. Starbucks saw the POG. It created the new experience for people, allowing them to take a few minutes out of their day to relax and enjoy the company of others or to read a good book.

Starbucks is a stark contrast to fast food and a shift from the classic diner. Here the emotion, ergonomics, aesthetics, complete identity, core technology, and quality VOs are at a maximum. Starbucks’ ability to capitalize on all Value Opportunities is an indication of its success. It even has strong impact VOs, with the creation of a social gathering place and its concern for the environment through recycled paper goods. The result is that Starbucks has high profit margin on their products (today we can pay more than $6 for coffee and milk under such names as latte, cappuccino, double espresso, and caramel macchiato). Starbucks has clearly demonstrated how value and strong identity enabled an expansion into more than 17,000 stores in nearly 50 countries, with products available in airports, turnpike rest stops, and supermarkets.

VOA of GE Adventure Series MRI

The VOA of the GE Adventure Series against the typical MRI equipment (see Figure 3.8) demonstrates the significant impact that the new and improved device has had on the journey of a child through an imaging process. Although typical MRI machines are highly reliable in terms of their core technology and their imaging results, the interface of the products lacked the fantasy value that the GE Adventure series has. The Adventure Series contributes value across the board. It builds a strong emotional connection with the child through story telling and creates an environment that motivates the child to voluntarily participate in the process and complete it as an epic mission. The entire room becomes part of the stage by stimulating a child’s different senses through sound, color, texture, and smell, resulting in an attractive, dynamic aesthetic. Its impact goes beyond its direct users, the children, and affects other stakeholders, such as parents, nurses, and physicians, and makes their experience in the imaging room less troublesome and still reliable. The value proposition is based on the interface design, but the overall impact is significant to the effectiveness of the MRI or CT scan experience.

Figure 3.8. Value Opportunity Analysis of the Adventure Series versus traditional MRI.

The Time and Place for Value Opportunities

Just maximizing the Value Opportunities isn’t enough to guarantee an Upper Right product. Two critical issues must be considered. The first is that mechanically finding ways to just increase the VO attributes, as you perceive them, is doomed to failure. The VOs must be maximized based on the product stakeholders’ perception of value. Furthermore, the VOs must work in concert to create a complete product in the Gestalt sense, not a set of features that each work in their own independent way to achieve an aspect of an experience. To enable a team to successfully reach a complete design requires a vision—and usually a visionary. Often a core team or even an individual has the vision of what the product should be—not in a detailed sense, but in the POG sense. In large companies, the visionary is often not part of the core team, but rather is a manager in the position to fund and protect the core team. Upper Right products don’t just satisfy POGs; they satisfy the vision of how the POG affects society and the SET Factors.

The second critical issue is to recognize that VOs are a representation of the SET Factors at a given point in time. SET Factors are dynamic. If the company does not keep a sense of the pulse of change in the target market as the SET Factors and VOs change, an Upper Right product today can easily become a Lower Left product tomorrow when a competitor recognizes the new SET Factors and creates a product to meet a more current POG.

VOs and Product Goals

The VOA chart is only half the battle. The chart captures which VOs are important, how important they are to the stakeholders, and how a potential product can differentiate from the competition. But it does not yet communicate how to achieve these VOs. The VOA does not apply generically to the design of all products. Instead, it provides the basis for developing product-specific goals. Each VO attribute needs to be interpreted within the context of the SET Factors and specific POG for a given market and user type. For each VO attribute, what must the product do to deliver on the designated level of value?

Figure 3.9 shows specific goals for each VO attribute for the FIT System. In these examples, a single product goal is given for any particular VO attribute. In reality, several product goals often emerge to deliver each VO. Knowing what customers want is the result of insightful user research, as discussed in Chapter 7. Those user insights are then mapped onto the VOA and the resulting goals provide an early set of product requirements. You don’t know what the product is, but you know what the product must achieve to maximize the value proposition.

Figure 3.9. Value Opportunity goals for BodyMedia FIT System.

Just claiming that a new product will maximize all the VO attributes would be easy. To be useful, the team must determine how the product will maximize each relevant VO. In examining the VOAs of the products in this chapter, it is clear that breakthrough products are able to “fill the white space” that remains in a VOA from the competitor or predecessor product. If a current-state VOA looks sparse, then an opportunity arises for a new product to deliver high value to the user. In some cases, it is only a particular VO attribute that differentiates the previous product from a potential new product; in that case, captivating the marketplace might be more difficult, but it will be obvious where to put the innovation effort: in that particular differentiating VO attribute.

With the VOA, you don’t know what the product is, but you know what the product must achieve to maximize the value proposition.

When the set of product goals is determined for each VO attribute, as many as 50 to 100 or more requirements can result. In this case, the team must prioritize the critical goals to achieve. Goals can be categorized into those that must be achieved, those that should be achieved, and those that could be achieved. An initial approach might be that all VO attributes rated high must be achieved, those rated medium should be achieved, and those rated low could be achieved. However, in some situations, either industry standards or areas that are not differentiated but are still necessary (such as with safety) must still be achieved. In addition, some product goals might be derived from a high value level but, in practice, might be less critical than others.

Having clarity through the Fuzzy Front End is often difficult. The process of using the VOA to capture user insights and develop product requirements can be a powerful driver of the iNPD process. This process typically makes downstream activities more effective and efficient, and helps guide the team to create a breakthrough product.

The Upper Right for Industrial Products

What is striking today is that Upper Right products that enhance experiences or fulfill dreams are emerging in all types of industries. Crown’s Wave (discussed in Chapter 11, “Where Are They Now?”) is one example of a product category (warehouse personal lifts) that previously had no recognition of the need for style and value. The Beyond Blast machining tool by Kennametal (in Chapter 9) is another. Electronic test equipment has found the value in adding style to an otherwise banal industry. Fluke’s consistent yellow-and-gray styling, clear brand identity, and ergonomic design separate its product from the pack.

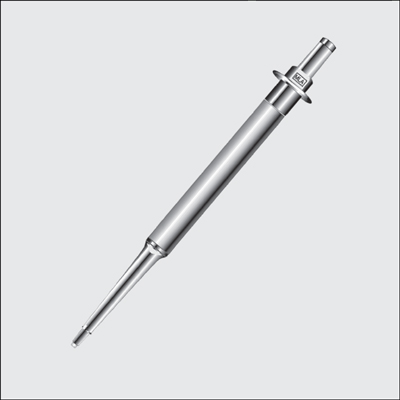

Even traditional commodity manufacturers are making the move to the Upper Right. VistaLab Technologies manufactures pipettes used in various laboratory applications, including sample preparation, reagent addition, and other precision liquid-handling tasks (see the accompanying sidebar). The company has been working closely with a major design firm to design ergonomic, styled products. The company recognizes that, even in the conservative laboratory supply industry, adding value through style and ergonomics adds to the experience of using the product and separates the company from the competition. By improving the balance and feel of a common laboratory tool, technicians can feel better about their work and themselves.

Dave Smith, leader of the design of the Wave, comments, “When you design a product you don’t change who the customer is. When you get up in the morning, you use your electric razor and clean yourself by dispensing soap from the pump container. You go downstairs and get ice and water from the door in your refrigerator. You get in your car and insert your key, and away you go.” All of these products are designed to meet your value needs, wants, and desires.

Smith then says, “You get to work and all of a sudden you are supposed to change? It doesn’t work that way. You have a basic expectation of product features and form. You evaluate your environment based on cumulative experiences.”

So if you are a manufacturer of clamps or bolts, why should your customer have to sacrifice what is expected in personal purchases? Think about an ergonomic clamp or bolt, much as VistaLab has considered an ergonomic pipette. Creating such an Upper Right product could significantly differentiate you from your competition and raise the level of expectation of the customer who needs to assemble your product.

In addition to enriching the work experience on the assembly line, consumers are now demanding an aesthetic for the interior of products. The trend began with the original iMac, where translucent exteriors meant that the aesthetics of the interior of the product mattered. End users saw each and every component, so the style of their assembly became critical to the overall success of the product.

The same is true in other products previously considered impervious to the issues of style. Engine compartments in cars must now capture the theme of the vehicle, even though the customer is likely to open the hood for the first and last time in the showroom.

From supplier parts to complete Original Equipment Manufacturer (OEM) products, high-value products are the leaders today. This and the previous chapter explained the characteristics that make a product move to the Upper Right. The book now turns to a process of how to get there—strategic commitment, brand management, and a well-developed, user-centered iNPD process.

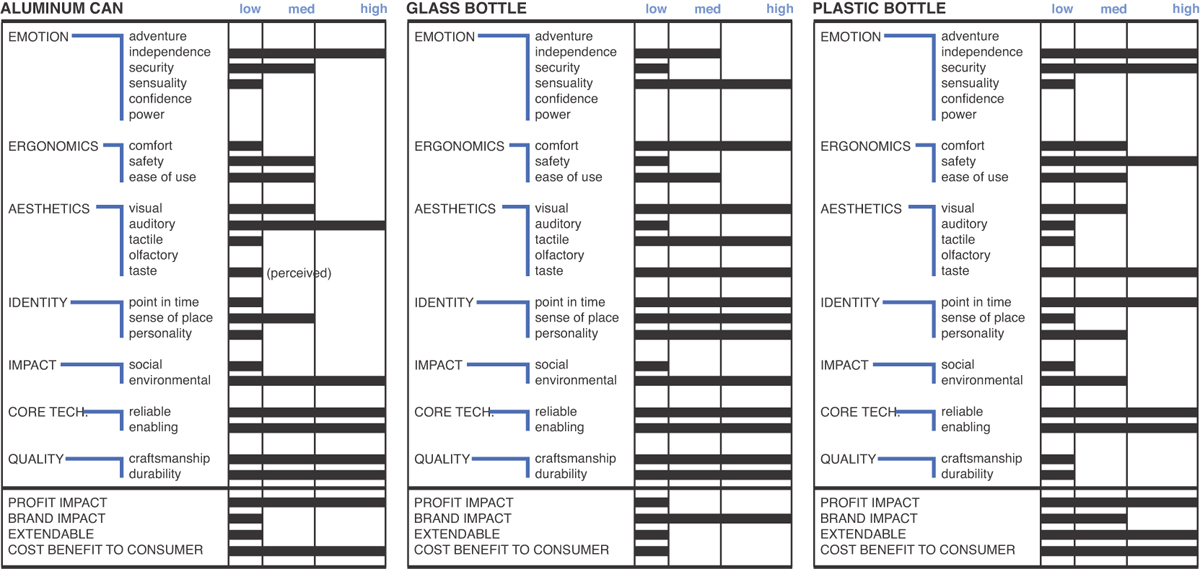

The Upper Right of Commodity Products: Trading off Value among the Aluminum Can, the Plastic Bottle, and the Glass Bottle

Value isn’t just for high-end products. Even commodities have a value proposition. A VOA highlights the benefits and challenges and a means to differentiate to manufacturers in these industries. Identifying points of differentiation creates an opportunity to develop better, higher-end products or to highlight differences in communications. For many years, glass bottles were the only containers for Coca-Cola. In the 1950s and 1960s, aluminum cans became popular, followed by plastic bottles in the 1970s. Each container carries both high and low value attributes. For the materials manufacturer, recognizing what advantages and disadvantages their material contributes to the value proposition is critical to differentiating future products, and the marketing and other communications about those products. Consider the VOAs of all three (see Figure 3.12).

Figure 3.12. VOAs of beverage containers: the aluminum can, glass bottle, and plastic bottle.

The glass bottle is clearly the most sensual, comfortable, and both visually and tactilely appealing of the three. It has a strong identity and stimulates fond memories of earlier times. It carries no taste and is perceived to be the most enjoyable to drink from. It is also high in its sustainability factor. However, it is more difficult to use, in that it is harder to open and has the potential to break, keeping the user less secure. The glass bottle manufacturer needs to leverage its strengths and turn the negatives into positives (such as the emotion and satisfaction of drinking the beverage after that cap is off).

The aluminum can is always easy to open, and the satisfying sound of the carbonation escaping augments the experience. The aluminum can is strong in sustainability, an attribute that makes it more desirable than the plastic bottle. But there is a perception (even if false) that the aluminum leaves a taste in the beverage, and the experience itself of drinking from the can is unexciting and unappealing. The aluminum can manufacturer needs to highlight the environmental benefits of recycling cans over using plastic. Aluminum manufacturers have developed a container in the shape of the bottle with a screw top to compete with glass and plastic, but it is not clear how competitive it is.

The plastic bottle is the most secure; the bottle can be resealed when it’s not being used. It is also the safest bottle, in that it won’t break and doesn’t have the sharp edges of a can. It can be molded to comfortably fit in the hand and can echo the form of its distant cousin, the glass bottle. But it is flimsy to hold and generally unattractive. And it leaves a negative footprint on the environment; even if it is recycled, the cost of reusing the material is high and the reused material has limited applications. The plastic bottle manufacturer needs to emphasize the safety and ease of use while indicating that there are recycling possibilities.

Summary Points

• Value is no longer the most features for the lowest cost. For breakthrough products, value is lifestyle driven, addressing the qualities of a product that make it useful, usable, and desirable.

• Breakthrough products fulfill a fantasy by facilitating a more enjoyable way of doing something.

• Seven basic Value Opportunities differentiate a product and contribute to the overall experience of use: emotion, aesthetics, identity, ergonomics, impact, core technology, and quality.

• VOs are relevant at a point in time and within the context of a product opportunity. They provide the basis for developing product-specific goals to meet the needs at that time.

• All industrial products are candidates for the Upper Right by addressing ergonomics and lifestyle effects in conjunction with technology features.

References

1. Webster’s New Collegiate Dictionary (Springfield, MA: G. & C. Merriam Company, 1973).

2. B. J. Pine II and J. H. Gilmore, The Experience Economy (Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 1999).

3. Ibid., p. 24.

4. P. B. H. Boatwright and P. Cagan, Built to Love: Creating Products That Captivate Customers (San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler, 2010).

5. J. Pirkl, Transgenerational Design: Products for an Aging Population (New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1994).

6. G. Covington and B. Hanna, Access by Design (New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1997).