7. Rewarding Innovation: How to Design Incentives to Support Innovation

The Importance of Incentives and Rewards

Incentives and rewards are some of the most powerful management tools available. When Mobil (now part of Exxon Mobil) changed its measurement system to support the introduction of its new business model, it linked 30% of the bonuses of all salaried employees to these metrics. A significant part of Mobil’s improved measures tracked the ability of the organization to learn better ways to execute the business model. At the corporate level, measures such as the growth in nongasoline revenues were used to reflect the value of incremental innovations to the model. At the division level, the company measured new product return on investment (ROI) and new product acceptance rate. As a result, Mobil moved to the number-one position in the industry.

However, be careful what behavior you reward—you might just get it. A high-growth startup company just acquired by a large pharmaceutical company (let’s call it ATH Technologies) faced the problem of motivating its employees to reach the sales and profit goals associated with the earn-out structure of the acquisition. Subjective bonuses, top management encouragement, and a performance-focused culture had been unsuccessful in reaching the goal. Then top management changed the incentive scheme of each employee in the firm. Everybody would receive a 30% bonus and a trip for two to Hawaii if the sales and earning goals were met. The incentive system linked to the financial goals was very effective, and the company reached its growth goals. However, after the trip to Hawaii, the FDA discovered significant quality problems in the products shipped, and the company was threatened with closure. Measures and incentives are powerful, but they should be carefully designed and balanced with the rest of management tools, including risk management.

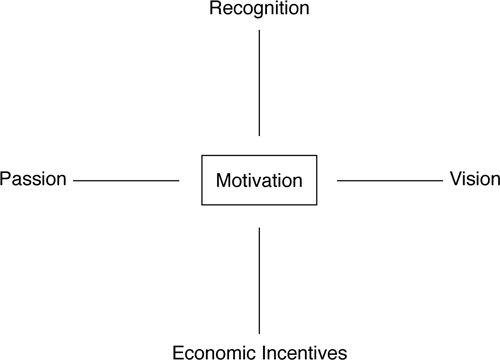

Motivation

People engage in an activity because of these elements:

• The expected incentives associated with the activity

• Their passion about the activity

• Trust that they will be appropriately recognized

• A vision that provides a clear sense of purpose

Designing adequate reward systems for innovation needs to take into account these four elements (see Figure 7.1).

Figure 7.1. The four elements of motivation

Some important rewards do not happen through explicit management systems in the organization.1 They happen within the realm of personal interactions: a casual conversation in which the chief engineer praises the work of an engineer over a cup of coffee; the team leader’s satisfaction when her team members are committed to the project, enjoy their work, achieve winning results, and grow as people; a boss’s appreciation for the effort in executing a risky project even though it does not succeed; or the personal satisfaction of seeing the results of one’s effort implemented.2 As one manager we interviewed plainly put it, “One thing about technology people is, money is important, but food is extremely important.”

Different Strokes for Different Folks

Incentives are designed before an innovation effort starts, and they link performance measures and rewards.3 Philips, the Dutch consumer electronics company, links the bonus of its product development teams to meeting release date targets specified before the project starts. The size of the bonus depends on the difference between the target and the actual release date. Volkswagen links the promotions of the design team to performance, including hitting the schedule and budget milestones.

In contrast, recognition is a reward that occurs after the outcomes of the project are available, even if no prior contract was in place linking performance to rewards. Recognition rewards are based on subjective assessments of the value generated. Inviting a development team to a hockey game after it has successfully finished the project even though the “contract” did not require it is part of a recognition system. Assigning the manager to a more important project or simply enabling peer recognition is another way of recognizing a project manager’s performance.

A European company had been researching for several years a new material for brain surgery clips that temporarily close blood vessels during surgery. Conventional metal clips were affected by magnetic fields and moved during brain scans. The improved clip they were searching for needed to have the same ability to close blood vessels but be nonresponsive to magnetic fields. The head of the research team said that an important part of what kept the team going during the long search was the internal drive to solve the problem and the strong interest that the CEO showed.

Some people innovate because they have a passion about what they do, not because of extrinsic rewards. People who are deeply interested in their work are self-motivated and are less influenced by external factors.4 An R&D manager in one major car company described his development teams as being heavily motivated by their strong interest in car technologies and their desire to bring the best ideas to market.

Formal reward systems are well suited for incremental innovation, such as increasing the efficiency of a manufacturing plant or improving quality through quality circles. Incremental innovation projects have a clear problem to solve. The solution to the problem can be translated into targets and linked to rewards. For instance, when the problem is that a product is too expensive, the solution is to incrementally redesign the product to achieve a 30% cost reduction. This specific target can then be linked to rewards, providing strong reinforcement to solve the problem.

Incentives are much harder to use for radical and semiradical innovations because the targets are not well defined and often change during the course of a project. Radical innovations rely more on recognition as a reward. Art Fry’s recognition as the father of Post-its is a major, long-lasting part of his reward. Using recognition to reward radical innovation gives an organization the flexibility to adjust the reward to each individual project, team, and person.

The rise and fall of the dotcom bubble was partly attributable to too much focus on incentives. People started companies with their eyes on the prize of a successful IPO (initial public offering) rather than the value and excitement connected with the development of a semi-radical or radical innovation.5 The passion for creating something new didn’t drive the teams; the downstream financial reward did. Now that the bubble has burst, venture capitalists are going back to their roots: investing in new technology and business models led by individuals and teams that are passionate about their innovations.

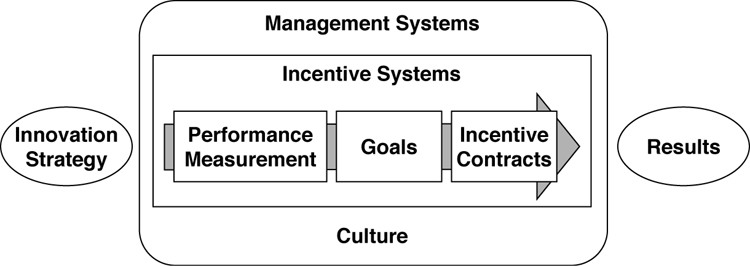

A Framework for Incentive Systems’ Design

An incentive system should reinforce a company’s innovation strategy, whether it is Play to Win or Play Not to Lose. It is vital to design incentives so that they motivate people to work together to get where the company wants to go. Nikon, the Japanese camera manufacturer, defines very clear goals for the teams designing the cameras for the upcoming season. The goals specify the release date, product size, image quality, and, most important, cost. Nikon uses target cost goals and incentives to ensure the profitability of the product. Figure 7.2 presents the key elements of incentive systems’ design.

Figure 7.2. A framework for incentive systems’ design

The goals for more radical innovations are less specific. When Guerrino de Luca took over as CEO of Logitech, the world leader in computer peripherals such as mouse devices, the company had reached a sales plateau of $400 million. His goal was to take the company beyond the current sales plateau, and he was encouraged to use new business models and consider new technologies. During the next seven years, he complemented the company’s main (and almost only) product, the computer mouse, with a host of new products: keyboards, webcams, cordless peripherals, and joysticks. He moved the company from being mostly an OEM supplier to becoming a household name and expanded its marketing efforts worldwide. Through small acquisitions and lots of internal innovation efforts, Logitech reached sales of $1.26 billion by the end of fiscal year 2003.

Different projects need their own distinct goals. Applied Materials’ integrated circuits manufacturing machines work with technology at the edge of existing particle physics knowledge. Intel, one of Applied Materials’ main customers, requires its production lines to be 100% flawless—exact replications of the first one installed to produce a certain chip. This is because the underlying physics are not fully understood, and even minimal changes may have horrible effects on productivity. The main criterion at Applied Materials is performance, at almost any cost. This is a significantly different cost priority than Nikon uses.

Once goals have been set, team and individual incentive contracts are defined to establish the formal link between performance and rewards. The incentive contract can be based on a formula that links performance against goals and prescribes payoffs. For instance, being on time nets a $1,000 bonus for each team member. However, it is also common to use performance against goals as an input to a subjective performance evaluation. At Johnson & Johnson Medical Devices and Diagnostics, product development leaders are chosen from different business functions. Leading a development team is only one of the tasks that they do throughout a year. At the end of the year, a product development leader’s supervisors gather to evaluate the person and decide his or her reward. The performance as leader of a development team is only one input to the evaluation; the evaluation committee determines how it is weighed.

The advantage of subjective performance evaluation is that it allows for interpretation of the information that the measurement system provides and adjusts for events that the “hard” numbers do not adequately reflect. A formula-based incentive system cannot adjust for the negative impact of the unexpected bankruptcy of a key supplier of technology. A subjective incentive system can account for it and reward the manager more fairly.

The final step in the design of incentive systems is defining the actual rewards. Companies can provide rewards in multiple ways: bonuses, prizes, stock options, and promotions, just to mention a few. Larger companies tend to rely on cash bonuses more than startups, which often rely on stock-based rewards. Each one has its advantages and limitations, and no hard-and-fast rules apply regarding which to use when. Management needs to ensure that they have been combined optimally.6

Incentive systems do not work in isolation; they act inside an organization in the context of its own culture and management systems. Incentive systems must be aligned with the culture and systems to be effective. One startup company in Silicon Valley that was in a hurry to get to market simply copied the incentive system from a competitor. The employees of the startup rebelled because they felt that the incentive system was inherently unfair; it did not fit their operating style and culture. The company was forced to start from scratch and design incentive systems that fit its situation.

Setting Goals for Measuring Performance

Without clear goals, innovation metrics lack a clear reference point from which to evaluate progress. The power of the incentives then is blunted.

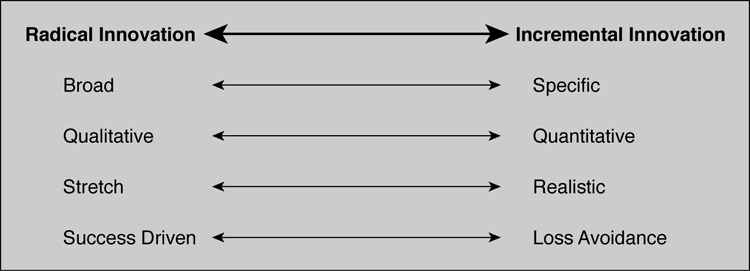

Goals vary across several dimensions:

• Specific vs. broad

• Quantitative vs. qualitative

• Stretch vs. realistic

• Success driven vs. loss avoidance

Specific vs. Broad Goals

Goals can be specific, as in “Reduce the cost of the mousetrap by 7%,” or broad, as in “Build a better mousetrap.” Both have their place. Goals for incremental innovation projects should be specific, as with Nikon’s focus on a specific camera at a predetermined cost.

With clear, specific goals, incremental innovation projects can be managed by exception—in other words, managers intervene only if there are significant deviations. An exceptional deviation (either good or bad) is investigated to understand the underlying cause. It may indicate underestimated risk or perhaps bad execution.

Exceptional deviations are not always a “problem.” They may actually lead to larger innovation opportunities. Once identified, these opportunities can be pursued within the current project or, as in most cases, spun off into a new innovation project. Post-its was an instance in which an unexpected discovery led to an unanticipated innovation. While 3M’s researchers were searching for a super-strong adhesive, they developed many less than satisfactory adhesives. That is par for the course in material research; you need to create many unacceptable experiments before you find the right solution. One of these adhesives caught the eye of Art Fry, who was looking for a material that would allow someone to affix a piece of paper multiple times without leaving any adhesive residue. He had gotten the idea when his choir bookmarks had fallen out; he wanted a bookmark that would stick without damaging the book. The new adhesive performed better than expected in the bookmark role. That intersection of the less than acceptable adhesive and Fry’s concept for marking his place in the choir notes was the beginning of Post-its.

As product development initiatives take on more risk and shift toward radical innovation, goals necessarily become broader and less specific. Think about Logitech’s new CEO’s goal of moving the company beyond its current sales plateau. Radical innovation requires experimentation, trial and error, openness to new ideas, and exchange of knowledge. Such freedom can be achieved only with goals that give managers flexibility.

Broad objectives stimulate constructive conversations between the project team, partners, other groups in the company, and top management. These discussions help the team better understand the strategic intent of top management. They also help senior management understand new strategic opportunities that were not easily articulated earlier in the process, when the broad objectives where first described. Logitech’s development of the IO Digital Pen, a pen that memorizes whatever it writes exactly in the place it was written and downloads it into a computer-readable file, is an example. Logitech’s CEO defined the company’s product space as “last-inch” interfaces between humans and technology. With this broad definition, marketing and engineering went around the world interacting with suppliers, customers, or simply interesting people. They bumped into the technology behind the IO Digital Pen at a fair in Europe. At the time, the technology was applied to a totally different product, but the Logitech team saw how it could be transformed to lead to a “last-inch” product. Ongoing interactions among various groups in the company distilled the product concept, created a business model unique to the characteristics of the product, and provided a clear, specific example of the broad “last-inch” goal—one that was not evident at the onset.

Quantitative vs. Qualitative Goals

Goals can be quantitative or qualitative. As a rule of thumb, incremental innovation projects tend to be more amenable to goals that can be easily quantified, such as time-to-market, level of resource consumption, and incremental changes in product performance. Quantitative goals for innovation usually have a specific time horizon: “Develop LCD screen TV by 2002.”

Goals for radical and semiradical innovation use more qualitative criteria because of the inherent uncertainty. Relying too much on quantitative goals may narrow the scope of the innovation effort and preclude the much-needed room for experimentation. Examples of qualitative goals that are being pursued today include “Develop a cure for AIDS” or “Create a viable business model for photovoltaic energy generation that does not rely on government subsidies.”7

Stretch vs. Expected Goals

Goals also vary in terms of how demanding they are. Incremental innovation projects should have goals that are clearly attainable and realistically set. When Citibank first started to demand and reward branch managers on customer satisfaction, it set a target of 80%. This target was chosen to be demanding but feasible. Having set the target at a very aggressive level of 100% or even 95% would have been so hard to hit that it would have been demotivating; managers would either ignore it or overinvest trying to reach it.

Goals for radical innovation projects should be stretch goals. These goals demand more than what most people would consider to be easy to attain or even realistic (in the sense of being easy to imagine and expect). When Microsoft spelled out its original vision of “a PC in every home,” it did not expect to reach the goal in the near future. Its goal was to inspire employees but also customers and society to think about the importance of the PC and how to make it available to everybody.

Radical innovation goals have to be inspirational. The people in the team (or organization) must feel as if they are part of something special, part of a feat that has never been accomplished. The goals must spark an internal drive to succeed that does not exist within business as usual. Stretch goals should be used to stimulate discussion, exploration, experimentation, and exchange of ideas. They should force people to ask questions like “What is the right way to think about this?” and “What kinds of experiments will move us closer to understanding how to do this?”8

Success-Driven vs. Loss-Avoidance Goals

The last dimension includes success-driven goals versus loss-avoidance goals. When Applied Materials was designing machines to manufacture its 65-nanometer (nm) chip, success was defined as achieving the 65nm performance level, at required quality levels, on time. These are success-driven goals (meaning, they define success). They are based on the key success driver of the project, whether it is time-to-market, product cost, or product performance.

In addition to the on-time, success-driven goals, Applied Materials’ products must be developed within a certain budget and within a certain product cost to be economically sound. These are loss-avoidance goals. As long as they are not exceeded, they are a marginal part of the innovation process. However, if the project reaches the limits set by one of these goals (such as product cost), the project is running into a dangerous zone: It may achieve the key success-driven goals but fail because it exceeded one of the loss-avoidance goals.

Loss-avoidance goals are usually tighter for incremental innovations, where the margin to redefine a project is smaller. Because of their inherent uncertainty and larger potential payoffs, radical innovations have more slack in their loss-avoidance goals.

In summary, radical innovations typically employ goals that are broad, qualitative, stretch oriented (that is, aiming beyond what is thought to be attainable through normal effort), and success driven. Figure 7.3 depicts the range of characterizing goals for radical and incremental innovations and summarizes this discussion.

Figure 7.3. Characterizing goals.

Performance Evaluation and Incentive Contracts

Goals are the reference point to evaluate performance during project execution and when the project is complete. In evaluating performance, several issues should be considered:

• The balance between team and individual performance measures

• Subjective vs. objective performance evaluation

• Relative vs. absolute performance evaluation

Team vs. Individual Rewards

Innovation projects are team efforts. Team members have a common objective: to achieve the goals set out at the beginning of the project. They should have an incentive to collaborate and support each other’s work. However, many companies block the effectiveness of teams by having inadequate incentives.10 On the other hand, the individuals on teams may deserve rewards because of their performance. The performance evaluation system cannot ignore important individual efforts; otherwise, the system is perceived as inequitable, dissatisfaction will grow, and the innovation effort will be adversely affected.11

Team effort and spirit may be undermined if certain team members carry most of the load while others have a free ride. As one manager described her experience, “I was working more than 15 hours a day most of the time seven days a week. I was doing the analysis of every single project performance. I quit because I thought it was unfair to do all the work and then everybody get the praise.”

To avoid the possibility of a “free rider” (a team member who does not do his or her share of the work), the team leader should be empowered to choose team members or at least replace a team member that he or she does not feel is contributing to the group. Another option is to complement team-based measures with evaluation and incentives for individual members. But whereas objective performance measures typically exist for teamwork—for instance, whether the project was on time, on budget, or on specifications—they are almost nonexistent for individual team members. Individual performance evaluation needs to rely on subjective assessments. The team leader may evaluate the performance of each team member or use a 360° evaluation mechanism in which the people who work with a person evaluate him or her. These individual evaluations help avoid the free-rider problem.

Incremental innovation typically uses formula-based team incentives supplemented with individual performance evaluations and incentives. A development team working on a new energy technology received a cash bonus upon successfully completing the project. In addition, the individual team members were rewarded in the annual review process with bonuses, salary increases, and, in some cases, promotions.

Companies can also offer profit-sharing or gain-sharing mechanisms. Profit sharing, used when the team is the division, encourages collaboration throughout the division. As the size of the division increases, the effect of profit sharing to motivate project teams decreases. For large divisions, excellent innovation team performance may end up uncompensated because the rest of the division performed poorly. Think about the Marks & Spencer store that significantly improved its operating performance in the early 2000s; what would have been the reward to the manager if the only performance measure used to determine the bonus was company performance? Given the poor performance of the British retailer during that interval, the bonus would not have reflected the store’s outstanding performance. Such dislocation between performance and rewards is very common when stock-related compensation is used in large companies. Although the team at the store may feel some kind of psychological solidarity with its co-workers, it also feels unfairly compensated.

Gain sharing links the value that an innovation project creates and the compensation of the team. Gain sharing typically leads to rewards throughout several years, as long as the effort is creating value. The longer time horizons of gain-sharing mechanisms have the advantages of measuring actual value creation instead of being a leading measure that is never a perfect predictor. On the other hand, the gains depend not only on the effort of the innovation team, but also on the efforts of the people who implement the innovation. Over time, other events impact the gains, and the initial effort is diluted among these other events.

Product profitability is a better measure of value creation than whether the product was designed on time or on budget. Most product-development teams are rewarded based on hitting certain targets at the date of market release. However, product-development teams could be more effectively rewarded on product profitability over time. The rub is that using profitability measures to reward performance requires more collaboration between the innovation team and the operating groups that manage the innovation in the commercial arena. That additional collaboration can be good for the company because it provides a more seamless path from innovation development to commercialization. However, the development team has less control over achieving the reward and depends on the quality of execution from operations.

Subjective vs. Objective Evaluation

Objective measures are the bread and butter of incentive systems, but they have limitations:

• They leave out important value levers. The main contribution of the original Honda U.S. team was not the initial sales of large motorbikes, but the team’s identification of a major market segment, small motorbikes, that Japan had totally overlooked.

• The more value levers that an objective measure captures, the more that uncontrollable factors distort it. Under the efficient markets assumption, stock price is the only measure that summarizes all the value created. However, stock price includes a lot of factors outside the control of the company, from interest rates to economic, social, and political events. For divisional managers, stock price includes the value that other divisions create, which the managers hardly control.

Subjective measures of performance should complement objective measures. Subjective evaluation has several advantages:

• Managers can include information not foreseen before the project started.

• Managers can observe actions and decisions of the person evaluated.

• Managers can evaluate tasks that are hard to quantify and judge, to determine whether they are beneficial to the company.

• Managers can discount the effect of uncontrollable events.

• Managers can adjust the importance of different measures and observations with changing priorities for the innovation effort.

• Because people interact in various issues and over time, a manager can use what he or she knows about the person evaluated to better assess performance.12

Subjective measures have their own limitations. They rely on the availability of information and the ability, knowledge, and effort of the person doing the evaluation. Subjective evaluation also relies on the supervisor having the right incentives to give a fair evaluation. This is not always the case. In fact, often managers have incentives to give good evaluations regardless of performance, to avoid the personal costs of an unhappy subordinate.13 Grade inflation at universities reflects this problem. Professors have no incentive to give a low grade because it leads to unpleasant interactions with students and potentially lengthy administrative processes. But grade inflation is not unique to universities. In describing her company’s process to us, a human resources manager said that although her company had five different levels of performance, 95% of the employees ranked in the top two levels.

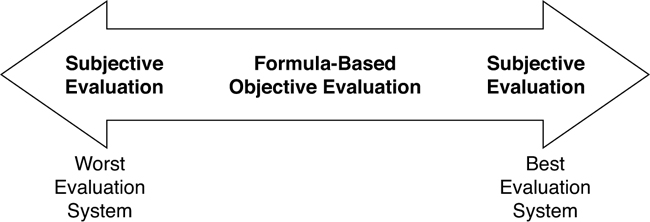

Probably the most severe limitation of subjective measures is that they rely on the reputation, fairness, and ability to judge of the evaluator. A person without credibility will hardly get a satisfactory evaluation (unless every single subordinate gets the top grade). Without these factors, subjective evaluation is worse than objective evaluation. Figure 7.4 illustrates this idea. Subjective evaluation can be the best performance measure when the person evaluating is competent, trustworthy, and committed, or the worst performance measure if any of these conditions is not met.

Figure 7.4. The role of subjectivity in performance evaluation.

Creating a mix of objective and subjective measures for evaluation is the best approach. Over-reliance on either one distorts incentives and behavior.

Relative Performance vs. Absolute Performance Evaluation

Goals can be set relative to the performance of other projects or initiatives, either inside or outside the organization. Relative goals are perceived as tangible and less “made up” than absolute goals. They also filter out uncontrollable events that affect the project and its reference target. When Mobil introduced a new measurement system, performance goals were set relative to competitors. Financial performance—ROCE (return on capital employed) and EPS (earnings per share)—was measured against Mobil’s top seven competitors. Bonuses associated with nonfinancial measures were linked to Mobil’s ranking in the industry.

Performance evaluated relative to peers inside a company motivates destructive competition. The Latin American division of a large software firm suffered from competition among its countries’ managers. Aware that the manager who showed better financial performance would get the division’s top job, countries competed against themselves. Although competition was a good stimulus to improve in-country performance, the division lost various deals that involved cross-national customers. The sale was booked to the country where the sales process was closed, regardless of the other countries’ involvement.

Relative performance evaluation also depends heavily on the existence of a comparable set of projects. This is more likely to happen for incremental projects, where the performance of other projects can come directly into the relative performance or into the definition of goals; it is unlikely to happen in radical projects.

Incentive Contracts

Companies need to decide the right percentage of compensation to make variable and the right mix of economic rewards. Organizations have different types of economic rewards available; most relevant are bonuses, salary increases, stock ownership and stock option plans, and promotions.

Compensation has four components:

• Expected level of pay

• Shape and slope of the pay–performance relationship

• Timing

• Delivery of the pay

Expected Level of Pay

The expected level of pay is the “market price” for a particular type of job. Compensation consulting firms develop reference tables for industries and regions that define “market prices” that companies use to set their level of pay. The inputs to these “market prices” are the characteristics of the job, including skills, knowledge, and competencies required. Some companies add a premium based on the characteristics of the person, in addition to job requirements. When pay is based on personal characteristics, the mechanisms used to determine the level are also based on skills, knowledge, or competencies.

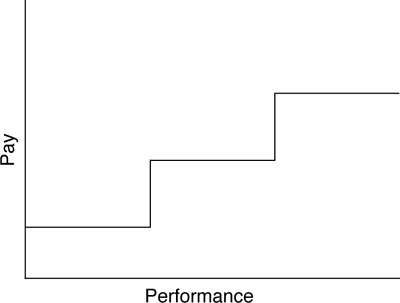

The Shape of the Pay–Performance Relationship

The second characteristic is the shape of the pay–performance relationship. For instance, Citibank used three different levels of pay: below par, par, and above par (as shown in Figure 7.5). Step changes are inferior to smooth linear relationships. A manager who knows that he is going to get par but sees very improbably that he will be able to move to above par may decide to limit his effort. A linear relationship would not generate this behavior because even small improvements are rewarded.

Figure 7.5. Problematic pay–performance relationship.

Most compensation systems are linear or close to linear. A linear relationship rewards and penalizes proportionally to the performance and, therefore, provides a constant incentive to improve performance. For instance, a distributor of electronic material facing problems with late deliveries put together a team to work on ways to improve its service. The goal for the team was to achieve 95% of the orders delivered within 24 hours. If the goal was achieved, the team would receive a bonus of 10% of its salary. For each percentage point above or below the target, the bonus would be modified by another 1%. The team mapped the process and investigated the various causes for late deliveries, ranging from the organization of the orders, the packaging people, logistics, and product availability. They gave top management a list of recommendations that were implemented to move the service to a 99% level.

This particular company had a lower bound on the shape of the bonus contract. Any performance below 85% led to no bonus. Having a lower bound is intended to protect against very negative performance. These lower bounds are set to protect managers from very negative outcomes that are mostly outside the control of the manager (if the manager is responsible, the outcome is dismissal of the person). In some cases, the shape also includes a ceiling that limits the upside potential. This avoids rewarding for favorable factors that are outside the manager’s control. A Canadian pharmaceutical company faced a problem associated with a lack of an upper bound. One of its divisions was the leader in a market with one other major competitor and myriad smaller ones. Competition between the two main players had kept margins low. The landscape changed when the FDA closed the production facility of the main competitor and left the division with little competition. Margins soared, and the division increased its yearly profits by 400%. Things returned to normal the following year, when exiting and new competitors added new capacity to grow in such a lucrative market. The division’s manager bonus on a typical year was around 30% of the salary, but that year, it was 350% of the salary (a similar proportion applied to other top managers). To make the problem even more acute, profit became the goal for the following year. Thus, the top management for the division was certain that the following year would have no bonus. An event that, to a large extent, was out of the division’s control was responsible for a windfall in bonus.

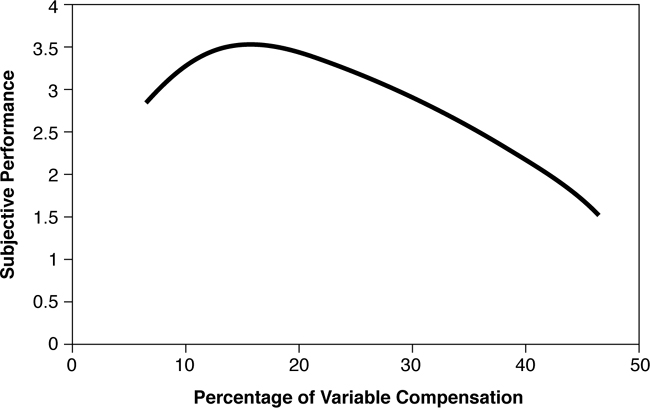

In addition to the shape, the slope of the relationship is a relevant parameter. Steeper relationships provide more incentives to deliver performance. On the other hand, too much pay-for-performance puts too much risk on the manager’s shoulders and leads to risk-averse decisions. Researchers in basic science seldom work under steep incentive schemes, favoring recognition systems. Research is too uncertain and too unpredictable. Instead, the opposite is more common. Research contracts are cost plus: A client such as the government reimburses the costs that the team incurs in the project. Cost-plus contracts remove economic incentives, and the team can focus its efforts on creating. Steep slopes also focus the manager’s attention too much on the performance dimensions included in the formula, at the expense of other relevant issues. The ATH Technologies case described earlier in this chapter, in which employees sacrificed the quality of the imaging systems to reach sales and profit goals, is a vivid example of how steeper slopes have to be carefully integrated with an appropriate culture and risk-management systems that limit the temptation to innovate in a way that is detrimental to the company.

Timing Incentives

Another characteristic of the incentive system is timing. Two issues are at play. One is retention of key employees through deferred and long-term compensation. One of the virtues of stock options is their vesting period, usually over five years. In Silicon Valley gatherings, it is common to hear managers sticking with a particular firm because their stock option plan has not fully vested. The other is the fact that the value an innovation creates, especially radical innovation, happens over long time horizons. The value of a radical innovation such as Virgin Galactic’s venture into space tourism can be assessed not on the basis of whether its development was on time or on sales in its first year, but on its impact over the next five or even ten years.

Stock option plans or restricted stock ownership plans vest over several years, with the objective of both retaining key employees and linking their incentives to the long-term performance of the company. Bonus payments can also be based on future performance. For example, the bonus associated with a process improvement innovation project may be a percentage of the cost savings that the company realizes over time. Again, this timing links incentive compensation to a measure closer to value creation and enhances employee retention.

Finally, in more sophisticated schemes, bonuses for excellent years are not fully paid out, but are kept in the employee’s “bank account” and paid over future periods if performance remains above expectations. If the performance falls in a particular year, instead of cutting the employee’s salary (a negative bonus), the company is paid out of the employee “bank account.”

Delivery of Compensation

The most common forms of delivering compensation are as cash (through bonuses) and through stock-related mechanisms. Cash incentives are better at motivating and rewarding actions that have short-term consequences, such as meeting milestones. Stock options and (restricted) stock awards are better at motivating a long-term perspective of the decision-making process and rewarding events that can be measured only after a long period of time, such as the success of a particular technology.

Another important issue relevant to stock compensation is its relevance in large companies. In large companies, the potential impact of the actions of a particular manager on stock price is almost negligible. Therefore, stock compensation is, for economic purposes, unrelated to the performance of the individual. How much can the controller of the Greece sales office affect the stock price of a Fortune 500 company? This person could just as well get any other stock in the Fortune 500 list because his or her effort has an imperceptible effect on the stock price of the company. The only benefits in these large organizations are the potential psychological effect related to “being owners.” This is especially true for incremental innovation; for radical innovation, the impact may be more significant, or the innovation can be spun out into a smaller company.

Key Considerations in Designing Incentives Systems for Innovation

The problem of most innovation incentive systems is that they reward the wrong behavior and provide disincentives for the right behavior. Add to that the powerful effect of economic rewards, and you end up with a dangerous force working against the objectives of the organization. In an effort to stimulate innovation, a bottling company decided to reward each suggestion with a small amount of cash; not surprisingly, it received a lot of suggestions, but none was useful. Most of the arguments against using incentives are based on this idea: Badly designed incentive systems are worse than nothing.14

The Danger of Overuse

Incentive systems can fail because they are overused. Putting too much emphasis on pay-for-performance without considering the risks involved may lead managers to shy away from risk-taking behavior. This, in turn, could lead to more incremental and less radical innovation in an organization.

The Negative Effect on Intrinsic Motivation

An additional challenge with innovation incentive systems is their potential negative effect on intrinsic motivation. Intrinsic motivation is the internal drive that a person has to do something purely because he or she loves it. This is a factor in all innovations, especially in semiradical and radical innovations. The manager who led the team that developed the brain clips that did not react to magnetic fields did it because of the challenge of the project and his passion to create something new, not because of the potential economic rewards. Sometimes the most important reward for performance is the act of doing the job itself.

Social psychology research as early as the 1950s found that external rewards could undermine intrinsic motivation.16 Research into intrinsic motivation in innovation has yielded similar results. A senior manager described it as such: “Research employees are often less excited about bonuses than about peer recognition.” Extrinsic rewards can actually drive away intrinsic motivation.17 In this case, a reward system may have the effect of focusing product development managers’ attention away from relevant dimensions: “Planning and rewarding for schedule attainment are ineffective ways of accelerating pace.”18

The promise of money if certain goals are met does not help creativity.19 It cannot make a job more interesting or enjoyable for an employee, and in some cases, it generates a negative impression because it is perceived as a bribe. It is important to understand that genuine interest in the work is usually the launch pad for creativity.20 This interest in doing something exciting with new technology is what drove Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak to develop the first personal computer in their Homebrew Computer Club—and, ultimately, to found Apple Computer.

Fear, Failure, and Fairness

The level of risk taking that a company encourages is important to consider alongside measuring and rewarding. Risk-taking behavior is necessary for successful innovation, but it can be killed if the company punishes failure either economically or socially. In one company, the CEO publicly abused a team of innovators because an initiative was apparently failing: They were threatened with no promotions or worse. No amount of financial compensation could offset the message sent to the entire organization about innovation: “Do not fail, or you will be humiliated and punished.” This created near paralysis in the organization, and innovation efforts ground to a halt. Laying off innovation staff when a business downturn occurs also sends strong signals to the organization about the value placed on taking risks.

Incentives and Rewards, and the Innovation Rules

So far, we have considered innovation to be a positive force: Companies want more innovation because it leads to value creation. But there is a dark side: Innovation can also destroy value (see Figure 7.7).

Figure 7.7. Innovation as a positive and negative force

Innovation driven by goals and incentives can add value and create growth. Unchecked and unbalanced, however, innovation can have a dark side that can put a company at risk. Kidder, Peabody, the oldest investment bank at the time of its demise, disappeared because of too much innovation. One of its traders was innovative enough to find a clever way to generate “profits” that did not exist but for which he was handsomely rewarded. Unfortunately, the company ignored various warning signals until it was too late. The cumulative losses led to the death of a venerable bank. A strong set of ethics may help take care of a situation like this, but it is also necessary to put risk-management systems in place to provide checks and balances.

Cash-based incentive systems using performance measures with a large component of formula-based evaluation are best when innovation initiatives have short-term results, smaller impact on overall organization, easily measured performance, and a relatively easy way to describe expected performance. As innovation initiatives incorporate a larger amount of radical innovation, incentive systems should be based on long-term incentives (stock-based incentive systems) and subjective evaluation.

Figure 7.8 summarizes the major differences that should be considered when designing incentive systems for radical vs. incremental innovation.

Figure 7.8. Summary of differences in incentives and reward systems for incremental and radical innovation

For radical innovation initiatives, recognition systems play a much larger role. In particular, managers participating in these projects need to feel rewarded for taking the risk even if the project was not successful. Alternatively, they must feel that they receive a fair share of the value generated from the project if it succeeds. Because effort, risk taking, and value generated from a project can be fairly judged only when the project is finished, incentive systems are ill suited for this task. Reward systems are better suited to this purpose.

Incentives provide a major impetus for behavior change. Without measures and incentives, organizational antibodies are released that resist innovation and block organizational change.21 Incentives can also cement in place beneficial behavior, creating a solid foundation for innovation.