3

QUALITY TIME IN HEALTHCARE

Meaningful Use of Health Information Technology and the Journey to Paying for Value

Contents

Introduction: The State of Our Current Healthcare System

Drivers of Change to Promote a More Productive Industry

Assessing and Redesigning Your Practice

Information Technology Strategies to Use Gains from Meaningful Use to Improve Quality and Value

Policy Priority 1: Improve Quality, Safety, Efficiency, and Reduce Health Disparities

Policy Priority 2: Engage Patients and Families

Policy Priority 3: Improve Care Coordination

Policy Priority 4: Improve Population and Public Health

Policy Priority 5: Ensure Adequate Privacy and Security Protections for Personal Health Information

Meaningful Use: The Road Ahead

To foster healthcare quality and satisfaction, the time health professionals and patients spend interacting with each other should be quality time—important, informative, productive, meaningful, and interpersonally connected. High-quality care is supported when providers, patients, and family members can interact in a mutually convenient and productive manner, with the right information available at the right time and in the right format to effectively and efficiently support the best possible health and care decisions and actions. Recent advances in health information technology (IT) and electronic health record (EHR) adoption and use have helped address our historical overreliance on paper-based care processes and clinical information flows that contribute to the enormous waste and waiting in the current U.S. healthcare delivery system, taking time, energy, and resources away from activities that can improve the value of healthcare. However, clinical information systems that are poorly designed, inadequately implemented, not meaningfully used, or not optimized to transform care also represent barriers to clinical quality and workforce productivity goals. In this chapter, two practicing physicians and clinical informatics leaders share their experiences with leading organizational change, healthcare process redesign, EHR implementation, and information management improvement strategies, as well as their experiences in the first five years of the Meaningful Use (MU) incentive program, to provide a perspective and recommendations for providers and organizations seeking to use health information technology (HIT) to achieve national goals for meaningful use and to be successful as payment policy transitions from traditional fee-for-service medicine to payment for quality and value.

Introduction: The State of Our Current Healthcare System

When it comes to delivering healthcare in the United States today, the fable Our Iceberg Is Melting1 is a fitting metaphor for the disastrous health and economic consequences our country and people will ultimately face if leaders fail to act quickly enough to transform care in a manner that dramatically improves quality and value. In the iceberg fable, noted change leadership expert John Kotter and colleagues illustrate the plight of a colony of penguins coming to the sudden, if not unanimous, realization that their iceberg—the basic foundation of their lives on which they all depend—was at great risk of collapse. Despite the implacable nay-saying of a vocal penguin in the leadership group that argued that change was both unnecessary and dangerous, the influential majority of penguin leaders soon recognized that the survival, health, and happiness of the colony they serve and protect required quickly achieving a shared sense that the status quo was unacceptable and that effective action was urgently needed. The leaders also realized they must come together as a guiding coalition, create a shared vision of a better future, communicate it widely and repeatedly, remove barriers to effective action, gain visible and meaningful short-term successes, reinforce and build on each success, and anchor the improvements in the culture. Finally, the authors provide a framework strategy for survival and success that builds on Kotter’s previous work2 and is relevant to transforming quality in healthcare organizations of any size, from solo physician practices to large healthcare delivery networks.

Along the way, the iceberg fable provides abundant examples of the challenges we in healthcare face in seeing system problems clearly, changing longstanding habits, overcoming barriers to organizational culture change, engaging stakeholders, and consistently aligning our behaviors toward a shared vision of improved quality and value. Indeed, although this chapter focuses on how HIT can be used as a powerful tool to support quality at the point of care, such efforts will fall far short of their full potential unless they are paired with a reformed payment policy that rewards thoughtful health information management and quality outcomes.3

In his compelling novel Why Hospitals Should Fly,4 John Nance took many of the important lessons described in John Kotter’s work to the next level, as well as adding several of his own from the aviation industry to show just how important cultural change is to our ability to make the transformational changes needed to improve healthcare quality and safety. This compelling book is necessarily a fiction because it describes a hospital (St. Michael’s Memorial) that does not yet exist, one that has gotten everything working right and everyone working together with an intense focus on patient safety, service quality, interpersonal collegiality, barrier-free communication, and support for front-line caregivers. However, St. Michael’s seems both real and possible because it represents a combination of best practices and effective leadership that can be found in other industries as well as in real-world healthcare settings today. St. Michael’s chose to harvest the lessons learned and best practices developed in aviation and leading healthcare institutions and put them to work to dramatically improve safety, collegiality, communication, workforce vitality, process standardization, information technology support, and other elements of organizational care transformation. St. Michael’s and the professionals who work there provided a clear and detailed view of how an ideal healthcare environment would look and feel to those giving and receiving care. Like the novel’s protagonist, Dr. Will Jenkins, readers of Why Hospitals Should Fly4 may initially be discouraged at the gap between what is possible and what exists in our healthcare delivery system today. However, they can also find comfort and inspiration in the many examples of strategies St. Michael’s leaders used to transform the organization and overcome barriers to needed change.

For those less than convinced of the urgent need to transform the U.S. healthcare delivery system, a few statistics and a review of recent events may be instructive. For example, World Health Organization statistics from 20135 showed U.S. per capita healthcare costs to be second only to those of Norway and second only to the tiny Pacific Tuvalu islands in fractional consumption of national gross domestic product at 17.1%,6 with total health spending growing from $2 trillion in 2005 to $3.8 trillion in 2014. Although these much higher expenditures might be justifiable if the vast majority of dollars yielded consistently high value care, such appears to be far from the case. Indeed, it has been estimated that up to 30% to 50% of healthcare spending in the United States is “pure waste.”7,8 A 2008 PricewaterhouseCoopers report9 examined the issue of healthcare spending waste in detail, estimating that slightly more than half of the $2.2 trillion spent on healthcare in the United States at that time was wasteful. Major contributors included practicing defensive medicine (redundant, inappropriate, or unnecessary tests and procedures), excessive healthcare administrative costs, and the cost of conditions that are considered preventable through lifestyle changes (obesity, tobacco consumption). The authors of the report correctly recommended addressing these three major cost drivers by facilitating healthier individual behaviors; attacking overuse, underuse, and misuse of tests and treatments; and eliminating administrative or other business processes that add costs without creating value.

Not only have higher expenditures on healthcare in the United States failed to translate into higher overall quality, but also key quality and system performance indicators showed that the United States is actually lagging behind other developed nations.10 This is due in no small part to limited access to primary care services, with nearly 46 million individuals representing 16% of the U.S. population living without health insurance in 2005, with a significant proportion (13.4%, 42 million) lacking health insurance for the entire year in 2013.11 Unfortunately, underpayments for primary care, preventive care, chronic disease management, and care coordination, combined with high medical school debt and perceptions of primary care practice burdens, have combined to create a shortage of primary care physicians that contributes to limited patient access to care. Recent trends consistently show that U.S. medical school graduates increasingly eschew primary care12 for specialties in which their care duties are more focused and payments for care and procedures are higher.

The unsustainable nature of the growth in healthcare expenses is further reinforced by data showing progressively increasing numbers of Medicare beneficiaries accumulating at the same time that the number of workers paying into the Medicare system is declining.13 Among the factors contributing to healthcare expenses that have prompted calls for government action is the wide variation in use of tests and treatments without evidence that higher expenditures are associated with higher quality,14,15 and even some evidence of an inverse correlation.16,17 The impact of the primary care provider shortage on costs and quality18 and the urgency of taking action to address the problem are underscored by the evidence that primary care is generally associated with better preventive care,19,20 lower preventable mortality,21 and similar quality with lower resource consumptions than specialty care for certain conditions, such as back pain,22 diabetes, and hypertension.23

Unfortunately, the public debate regarding the preferred approaches for moving toward meaningful, beneficial, and enduring health reform remains mired in partisan political rancor fueled by powerful special interest groups with vested interests in the status quo. This has the effect of obscuring, distorting, distracting, and delaying discussion of the real and substantive issues that need to be worked out. In the meantime, our healthcare iceberg is still melting. Surveys such as those conducted by the Commonwealth Fund24 have made it clear that the public wants change to address healthcare quality, access, and costs. Desired changes included organizing care systems to ensure timely access, better care coordination, and improved information flow among doctors and with patients. Respondents also wanted health insurance administrative simplification and wider use of health information systems. Since there is compelling evidence that the status quo is not sustainable, it is important to look at potential drivers of change that will help us redesign care so that quality is a system property supported by appropriate and meaningful use of HIT.

Drivers of Change to Promote a More Productive Industry

Although this chapter focuses on strategies for combining change leadership, practice assessment, process redesign, and HIT to assist practitioners in optimizing care quality and value, it is important to cite a few additional writings and events that highlight problems with the existing healthcare delivery system, underscore the urgency of healthcare system redesign, and serve as powerful drivers of change that have also informed our suggested approaches. For example, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) has commissioned several books describing a number of pervasive and critically important defects in the U.S. healthcare delivery system and recommended strategies for addressing them. Two of the most important of these books, To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System25 and Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century,26 shone a bright light on the defects in the current system and how such defects compromise the nation’s ability to ensure the consistent delivery of high-quality care to all. Such defects result in care that is far too often fragmented, ineffective, error-prone, unsafe, inefficient, expensive, inaccessible, delayed, disparate, or insensitive to patient needs and preferences. The IOM also emphasized the reality that humans cannot be error free, and indicated that the healthcare delivery system must be fundamentally redesigned, not just repaired, if meaningful gains in quality are to be achieved.

Much has also been written in recent years about the essential role of HIT in repairing some of the pervasive and critically important defects in the U.S. healthcare delivery system. Here again, the IOM did pioneering work, publishing and subsequently revising a book on computer-based patient records,27 describing what would afterwards be more commonly referred to as electronic medical records (EMRs) and electronic health records (EHRs) as essential to both private and public sector objectives to transform healthcare delivery, enhance health, reduce costs, and strengthen the nation’s productivity. However, the IOM also correctly identified many barriers to widespread implementation of EHR systems and predicted the need for a “major coordinated national effort with federal funding and strong advisory support from the private sector”26 to accelerate needed change.

Some have estimated that approximately $80 billion in annual savings can be expected out of an estimated $2 trillion total (4%) from widespread implementation, optimization, and appropriate use of HIT,28,29 although a 2008 Congressional Budget Office (CBO) report30 underscored the degree to which this number may be sensitive to a number of assumptions and factors. The report also highlighted the current perverse incentives built into healthcare financing and delivery in which “the payment methods of both private and public health insurers in many cases do not reward providers for reducing some types of costs—and may even penalize them for doing so.”30 On the other end of the savings prediction spectrum, it has been estimated that if healthcare could produce productivity gains similar to those in telecommunications, retail, or wholesale industries, average annual spending on what is currently considered waste in healthcare could be decreased by $346 billion to $813 billion.28 It is this combination of the potential for significantly lowering wasteful spending, the evidence that the right combination of HIT and institutional culture can lead to important gains in quality and value,31 and the urgency of needed change that has prompted healthcare organizations and federal government officials to “bet on EHRs”32 by making funding available to physicians and hospitals to improve quality through HIT.

The “Game Changers”

The federal government placed its “bet” by introducing a new and powerful driver for HIT adoption and appropriate use on February 17, 2009, when President Obama signed the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health (HITECH) Act, a large component ($31.2 billion gross investment, $19.2 billion net of expected savings) of the much larger ($787 billion) economic stimulus package known as the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) of 2009.33 The HITECH Act made the IOM recommendation for a major coordinated national effort with federal funding a reality, with $29.2 billion ($17.2 billion net) available starting in 2011 for use as incentive payments to Medicare- and Medicaidparticipating physicians and hospitals that use certified EHR systems in a “meaningful” way.

ARRA also provided for the creation of two advisory committees under the Federal Advisory Committee Act (FACA) that would be charged with making recommendations to the National Coordinator. Both of these advisory committees have since been formed and are constituted in a way that is consistent with the IOM’s recommendations for involvement of experts from the private sector. The Health IT Policy Committee was given the responsibility of “making recommendations on a policy framework for the development and adoption of a nationwide health information infrastructure, including standards for the exchange of patient medical information,”34 while the Health IT Standards Committee has been charged with making recommendations “on standards, implementation specifications, and certification criteria for the electronic exchange and use of health information,”34 with an initial focus on the policies developed by the Health IT Policy Committee.

With codification into law of the National Coordinator for Health IT, improved funding for the Office of the National Coordinator (ONC), the passage of ARRA and the HITECH Act into law, and the appointment of the Health IT Policy Committee and the Health IT Standards Committee, energy turned to defining the goals, objectives, measures, and criteria by which physicians and hospitals will qualify for payments for meaningful use of HIT, along with the standards needed to support the goals for MU. ARRA authorized the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) to reimburse physician and hospital providers who are meaningful users of EHR systems by providing incentive payments starting in 2011 and gradually phasing down over five years. Meanwhile, physicians and hospitals not actively using an EHR in compliance with the MU definition by 2015 are subject to financial penalties under Medicare.

It is important to emphasize that MU does not mean simply having an EHR system in place and in use. MU requires physicians and hospitals to progress through a series of increasingly demanding sets of behaviors, proceeding from EHR use to capture and exchange data, then to improve care processes, and finally to achieve improved patient health outcomes. Payment for MU Stage 1 started in 2011 and required eligible professionals (EPs) to use certified electronic health record technology (CEHRT) in a manner that met specific measures for electronic data capture and sharing with a focus on five healthcare priority areas:

• Improving quality, safety, efficacy

• Engaging patients and families

• Improving care coordination

• Improving population and public health

• Ensuring adequate privacy and security protections for patients

Meeting the measures for Stage 1 MU was challenging but the majority of EPs who registered for the program were able to implement 2011 Edition CEHRT, attest for MU and receive incentive payments. Along the way, they expressed significant concerns about the complexity and lack of clarity of the MU and Certification Final Rules, the accuracy and limited relevance of clinical quality measures (CQMs) for some specialties, and the challenges of submitting attestation data or getting answers to questions. Additional concerns centered on the usability of EHR systems to deliver workflow-integrated approaches to data capture and sharing required to demonstrate MU. Of particular concern to physicians and congressional leaders was the lack of interoperability of CEHRT systems three years and tens of billions of dollars into the program. These concerns prompted a greater emphasis on advancing interoperability in Stage 2.

Meanwhile, CEHRT developers and vendors lamented that the time, effort, and resources required to plan, develop, test, certify, release, and assist customers in implementing CEHRT left them unable to apply proper focus on EHR usability or innovation to improve care. This problem was exacerbated by the complexity and late timing (September 2012) of the release of the Stage 2 MU Final Rule and the 2014 Edition EHR Standards and Certification Final Rule, followed by the challenges of developing, testing, and certifying 2014 Edition CEHRT.

The considerably greater challenges of developing, delivering, implementing, and utilizing 2014 Edition CEHRT for Stage 2, which was scheduled to begin in 2013 for some EPs, resulted in several CMS actions. First, CMS allowed a third year of Stage 1 attestation in 2013 for those who first attested in 2011. CMS subsequently relaxed its 2014 full-year reporting period expectation for ongoing incentive program participants, allowing reporting for a single quarter. For circumstances in which delays in the availability of 2014 Edition CEHRT did not allow an EP, eligible hospital (EH) or Critical Access Hospital (CAH) to fully implement 2014 Edition CEHRT, CMS also allowed for the use of 2011 Edition, 2014 Edition, or a mix of 2011 and 2014 Edition CEHRT to meet MU requirements in 2014.

Recognizing the ongoing challenges to fully implementing 2014 Edition CEHRT by the start of the 2015 reporting periods, CMS published an additional Proposed Rule35 modifying the MU program for 2015–2017, which was combined with the MU Stage 3 Proposed Rule and finalized on October 16, 2015, with a 60-day comment period, becoming effective December 15, 2015. The addition of a comment period to a Final Rule was unusual but necessitated by the passage of the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015 (MACRA) soon after the two Proposed Rules were published. Because MACRA called for the MU program to be incorporated into the Merit-Based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) and that separate MU EP payment adjustments cease by the end of 2018, the 60-day comment period allowed for input regarding the provisions related to the incorporation of MU into MIPS.

The Final Rule modified the MU program for 2015–2017 in several helpful ways, including (1) relaxing the 2015 reporting period (which requires use of 2014 Edition CEHRT) from a full 12 months to any consecutive 90-day period, enabling successful attestation for those who could not fully implement 2014 Edition CEHRT by January 1, 2015; (2) changing the reporting period for EHs and CAHs from the fiscal year to the same calendar year reporting required for EPs; (3) removing more than 10 measures that CMS believed to be topped out, duplicative, or redundant; (4) easing measures that required patient action not under the direct control of the EP (e.g., patientinitiated secure messaging); and (5) creating a single, synchronized MU stage (“Modified Stage 2”) for all program participants. Having all MU Incentive Program participants on the same stage simplified the program and promoted concurrent implementation and use of the same CEHRT functionalities by all, such as sending and receiving electronic Summary of Care Documents.

These challenges and subsequent modifications of the MU Incentive Program for 2015–2017 underscored the complexity of building a nationwide technical and human infrastructure for HIT-enabled care transformation from volume to value. However, the flexibility and openness to feedback demonstrated by CMS and ONC predicts continued positive progress toward the Triple Aim goals (patient experience and outcomes, health of the population, reducing per capita costs of care) desired by all.

Success in the national effort to use HIT to transform health and healthcare requires sustaining the engagement and vitality of the health professions workforce. This was tested by how CMS responded to comments received in response to the CMS MU Stage 3 Proposed Rule36 and the 2015 Edition HIT certification criteria, 2015 Edition base EHR definition, and ONC Health IT Certification Program modifications, which were finalized37 in the fourth quarter of 2015.

The major strengths of the Stage 3 MU Final Rule include (1) a single definition of MU; (2) continued synchronization of all EPs, EHs, and CAHs to a single stage; (3) further consolidating the number of measures to eight (though there are measures within measures, which approximately doubles this number); (4) allowing but not requiring electronic prescribing of controlled substances to count in states where it is permitted; (5) reinforcing the broad range of allowable approaches to implementing clinical decision support; (6) flexibility in public health and clinical data registry reporting; (7) allowing messages sent to patients to count for the secure messaging measure; and (8) allowing for patient access to their records through ONC-certified application programming interfaces (APIs; e.g., smartphone “apps”).

Some of the main criticisms and concerns that have been voiced about the Stage 3 MU and 2015 Certification Final Rules include (1) dissatisfaction with the continued reliance on highly prescriptive process measures, expensive and time-consuming to build for vendors, and not permissive of flexible and/or innovative workflows for providers; (2) continued emphasis on process measures over patient outcomes that foster “check the box” mentality over attention to improving outcomes; (3) the hope of decreased physician burden implied by limiting Stage 3 to eight objectives was replaced by disappointment when closer inspection showed that six of the eight objectives include two or three measures that must be reported; (4) the limited time EHR developers have from publication of the Final Rule (2015 Q4) to implementing 2015 Edition CEHRT to support Stage 3, especially for those seeking to attest for the 2017 reporting period; (5) the large number of 2015 Edition CEHRT certification requirements (22 of 60) that are not required for MU, raising concerns about diverting EHR developer resources and attention away from usability and innovation; (6) the pressure EHR developers will felt to release 2015 Edition CEHRT in time to support MU Stage 3 in early 2017, even if it means prioritizing certified functionality over usability, innovation, and workflow integration; (7) the requirement for certain patient actions, patient-generated data, or data from nonclinical settings that are outside the direct control of EPs, EHs, and CAHs, including the use of consumer apps and APIs that are not yet broadly available and in use; (8) challenges to small EP offices in conducting a robust security risk analysis and acting on the results; (9) the need for creation of a centralized repository of national, state, and local public health agencies and clinical data registries that support data submission; (10) the need to address problems with data validity, infrastructure, and workflows required to support mandatory electronic reporting of electronic CQMs by 2018 when attestation will no longer be an option; (11) anticipated time and usability challenges of meeting new requirements for clinical information reconciliation (problems, medications, allergies); and (12) the full-year reporting period for all but first year Medicaid MU participants in 2018, the first required year of Stage 3.

Although the first five years of the MU Incentive Program have not resulted in sufficient progress to enable full replacement of process measures with patient outcome measures, they have clearly catalyzed more widespread adoption and use of CEHRT than would have been likely otherwise. It also means that many physician practices and healthcare organizations are now equipped with the HIT infrastructure, EHR proficiencies, electronically stored clinical data, clinical decision support tools, and data analytics capabilities to measure and improve the quality and value of care for individuals and populations.

These capabilities will be critically important to provider and organizational readiness to respond to forces that are rapidly driving shifts in payment from volume to value. A clear example of this can be found in the January 2015 announcement by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) of its “Better, Smarter, Healthier”38 campaign (Better Care. Smarter Spending. Healthier People). In this campaign, HHS sets clear goals and timelines for shifting Medicare reimbursements from volume to value, by tying 30% of traditional (fee-for-service) Medicare payments by 2016—and 50% by 2018—to quality and value through alternative payment models (e.g., accountable care organizations [ACOs] or bundled payment arrangements).

In addition, HHS intends to use programs such as the Hospital Value Based Purchasing Program and the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program to tie 85% of all traditional Medicare payments to quality or value by 2016, and 90% by 2018. HHS further seeks to extend these goals beyond the Medicare program through the creation of a Health Care Payment Learning and Action Network, working with private payers, employers, consumers, providers, states and state Medicaid programs, and others to expand alternative payment models into their programs.

The importance and urgency of moving from volume to value, participating in alternative payment models, and continuing to focus on MU of CEHRT was also reinforced by the April 2015 U.S. Senate passage of H.R. 2—Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act (MACRA) of 2015,39 which passed with overwhelming bipartisan support in both chambers. This so-called “doc fix” legislation, signed into law (Public Law No: 114-10) two days later, permanently repealed the previous sustainable growth rate (SGR) formula that adjusted Medicare payments to physicians, replacing it with modest increases in Medicare physician reimbursement for five years starting in July 2015. Importantly, the law also combined and streamlined several quality, value-based payment, and MU incentive programs into a single new Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS). Under MIPS, the Secretary of HHS is instructed to use the categories of quality, resource use, clinical practice improvement activities, and MU of CEHRT in determining performance. Incentive payments will also be available beginning in 2019 for physicians who participate in alternative payment models such as ACOs and meet certain thresholds.40

So notwithstanding one’s feelings about the transition from paper to electronic systems and the merits and methods of the MU Incentive Program, “the ship has sailed” on the required transformation from volume to value, and HIT will be essential to payment for proving and improving the quality and value of healthcare going forward. As originally articulated in the HITECH Act, expectations for MU will continue to focus on the capture and exchange of health-related data using CEHRT to improve care processes and patient health outcomes. MACRA reflects a progressive emphasis on quality as reflected by clinical outcomes, so physicians and practices will do well to continue to focus on conditions that are common, important, preventable, costly, and highly amenable to treatment. Examples include diabetes mellitus, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, smoking, obesity, preventive care services, safer medication prescribing in the elderly, and prevention of venous thromboembolism in surgical patients.41 Efficiency and safety measures will likely continue to include avoidance of preventable emergency department visits and hospitalizations; decreasing inappropriate use of imaging studies; computerized provider order entry; use of evidence-based order sets; advanced electronic prescribing; barcode medication administration; device interoperability; multimedia support; advanced clinical decision support use; and external electronic data reporting on quality, safety, and efficiency.

Developing a Plan

Although the financial incentives available from the HITECH Act may have been sufficient to help providers and systems justify the capital expenditures required to implement and make meaningful use of EHR systems, it is the long-term payment reform outlined in the preceding section that creates a sustainable business case for managing information electronically and improving outcomes. MACRA consolidated the various quality incentive programs and the financial penalties for failure to achieve and sustain MU into a system that incorporates MU into a broader set of performance categories that determine incentive payments and negative payment adjustments.

We recommend that providers focus squarely on improving patient care quality, something that all health professionals resonate with and are individually committed to, and further begin to focus on value—the cost of achieving high-quality care. Physicians should be frequently reminded that they have a shared responsibility for quality,42 that their participation in EHR system configuration is essential to achieving the organization’s quality goals, and that having HIT is insufficient unless it is used in a meaningful way in an organizational culture strongly committed to quality, safety, and collegiality. By quality we mean the six elements described by the IOM in its Quality Chasm report:26 care that is consistently patient centered, effective, safe, timely, efficient, and equitable. This emphasis on quality (especially safety), collegiality, and support for those at the front lines of care is what enabled John Nance’s fictional St. Michael’s Memorial Hospital to make its transformational journey to quality in Why Hospitals Should Fly,4 and it provides a road map for how each of us can use our CEHRT to accelerate the transformation of our own hospitals and office practices in alignment with our main rationale for doing so, namely, ensuring that high-quality, high-value care is consistently available for all.

Although hospital executives, practice leaders, and front-line providers are increasingly mindful of the importance and urgency of acting on their responsibilities and opportunities for improving care quality while containing costs, they may also be currently using HIT systems and support structures beset with some of the same defects as the healthcare system they were intended to support, even several years into the MU Incentive Program. Such systems may have been designed and implemented without adequate clinician input, making them a poor fit for health professionals at the point of care. The systems may also still not “talk to each other,” either through product integration, interfaces or interoperability mechanisms, requiring redundant data entry and risking introduction of errors of commission or omission that threaten patient safety, care effectiveness, workflow efficiency, or service timeliness. Physicians also quickly learn to ignore systems that do not respond quickly or reliably enough for their needs, and develop workarounds that enable them to justify ignoring or underusing HIT systems or foregoing training opportunities even when they are available and encouraged.

Engaging physicians and convincing them of the importance of HIT to achieving shared organizational quality goals is a crucial early step that will increase the likelihood that they will be “willing to strive”43 to achieve meaningful EHR use. Assessing organizational HIT readiness44 is also important, as is ensuring that HIT systems are designed, built, validated, tested, and implemented with clinician input. We encourage design strategies that improve usability by decreasing the reading, writing, navigating, and thinking load45 to the minimum necessary to improve the user experience and help clinicians make and execute optimal care decisions.

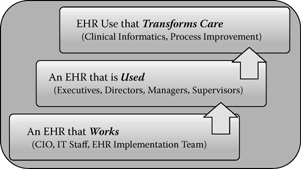

To speed care transformation and create a high-reliability organization that inspires the trust and satisfaction of patients and providers, HIT strategists should create, prioritize, and execute plans reflecting awareness of and responsiveness to the critical success factors and potential failure paths of major IT system implementations,46–52 incorporate approaches that encourage adoption and regular use of EHR systems,43 and manage the activities required by busy health professionals, taking into consideration the ongoing stressful care transformation process. Boiled down to its bare essentials, a successful journey to qualifying for meaningful EHR use requires building a successful three-tier care transformation framework (Figure 3.1) and then assessing and assisting users in moving from basic to advanced EHR use (Figure 3.2).

The foundational requirement in an EHR system-enabled care transformation framework (Figure 3.1) is an EHR system that works. This means that the IT staff and EHR implementation team combine to complete the IT technical infrastructure and build tasks required to deliver an EHR system that functions according to agreed on user requirements and is dependable and responsive. The second requirement is an EHR system that is used. This outcome is fundamentally dependent on the leadership and culture of the organization. Responsibility for physician engagement and alignment around a shared quality agenda,42 accountability all the way to the board of directors, and elimination of “normalization of deviance”4 from important policies and procedures regarding EHR training and use in patient care are all critical to quality and MU. All of these depend on the combination of formal organizational leadership and the building of a culture in which coworkers support each other in MU and correct themselves and each other when deviance from standards for appropriate use are observed. The third requirement is an EHR system that transforms care, which requires the clinical informatics leadership, expertise, and resources to formulate and execute the principles and strategies for use of HIT and EHR systems to accelerate continuous process improvement and care transformation.

Figure 3.1 Electronic health record system-enabled care transformation framework: Stepwise goals and change leaders.

Figure 3.2 Attitudes regarding use of information technology and stages of EHR use.

At the individual EHR user level, it is important to recognize the differences between people with regard to their attitudes about change and the adoption of new technology, as well as factors (incentives and inducements) that affect their willingness to strive to progress from simple data viewing and basic EHR use to become highly competent users and even system changers (Figure 3.2).53 Those with an EHR system already in place have most likely already identified the 15% or so of those IT optimistic individuals in their organization who are best characterized on the Rogers’ technology adoption curve54 as innovators or early adopters of IT. Supported by appropriate payment policy but otherwise with minimal encouragement, these individuals can be counted on to strive to become highly competent EHR users and will spontaneously help build enthusiasm for EHR adoption and MU by others as well. With appropriate training and support, some of these folks will become EHR champions or superusers who can be relied on to help other users make progress, try out enhanced EHR features and functionalities, or serve on EHR advisory committees.

Roughly two-thirds of the individuals in an organization can be expected to use the EHR early on only if it is communicated by leadership as a clear expectation, with monitoring and accountability. The early majority represents about half of this group and is more accepting of change than the more skeptical late majority. Understandably, executives can generally get behind expectation setting with accountability only when it is clear to them that the organization has installed an EHR that works, making it reasonable to hold people accountable for EHR training and regular, appropriate use.

However, inevitably the organization will be left with approximately 15% of its people lagging behind. These so-called laggards54 often simply prefer the old way of doing things. They tend to be suspicious and critical of new approaches. In some cases they not only prefer the status quo but may also inadvertently disrupt the change process or even deliberately “poison the well” for others trying to lead or implement sorely needed organizational change. Without the input of considerable energy from others, laggards are unlikely to use the EHR or to use it appropriately until it has become the way almost everyone else is doing their work. For some, they will use the EHR only when the old way (e.g., paper, transcription, verbal orders) is no longer provided as an option. Rarely, some would rather leave an organization than adopt the new technology. Informatics experts and clinical leaders commonly struggle to decide how best to deal with these individuals. At one end of the spectrum, they may either accept or manage the clinician’s unwillingness to adopt and use an EHR by allowing full exemption from EHR use (paper documentation with post-encounter document scanning and indexing), accepting “EHR light” use (dictation and transcription, viewing and signing results), or providing EHR-competent scribes. At the other end of the spectrum, employed laggards may face financial penalties or termination from employment if they are persistently unwilling or unable to become regular and meaningful users of the EHR system, while nonemployed laggards may face suspension or revocation of admitting or consulting privileges.

There are many trade-offs in any approach to resolving the problems associated with laggard noncompliance with EHR training or use expectations. Our advice is to set reasonable expectations and accountability for EHR use in advance and then measure, monitor, and enforce the expectations consistently. This should be done independent of rank, experience, or extent of push back about the adequacy of the system for use, particularly if other physicians and staff are consistently able to use the same EHR system to safely and effectively deliver similar care for similar patients using reasonable workflows. Failure to do so will simply teach others that foot dragging or negative behaviors are acceptable and effective ways of resisting needed change, while decreasing the morale of those who have exhibited the professionalism and dedication to strive to become competent and meaningful EHR users.

Assessing and Redesigning Your Practice

“Every system is perfectly designed to get the results it gets.”55 Although this is a sobering comment in light of the defects in the U.S. healthcare delivery system described previously, it also suggests the path to improved quality in healthcare—by carefully redesigning care, we can expect better results. The challenge is to identify resources and implement strategies that allow us to regularly deliver to our patients what Berwick and colleagues have termed the “triple aim”56 of better experience of care (patient-centered, effective, safe, timely, efficient, and equitable), better health for the population, and lower total per capita costs. Although front-line clinicians may feel they have limited ability to influence healthcare redesign at a macro level, each local care team working closely and regularly with each other to provide care to a specific group of patients constitutes a clinical microsystem that, through a process of practice assessment and redesign,57–62 can expand access,60 improve effectiveness, advance safety, enhance patient and staff satisfaction, decrease waste and waiting, and leverage HIT to automate otherwise cumbersome manual processes. The Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy and Clinical Practice maintains a comprehensive and useful set of clinical microsystem resources on its website,61 including Clinical Microsystem Assessment Tool62 and Clinical Microsystem Action Guide.63

Another rich source of useful information and tools for assessing practices and improving care delivery systems is the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) website.64 Particularly relevant and helpful resources include improvement methods,65 presentation handouts from previous annual international summits on redesigning the clinical office practice,66 and white papers,67 including topics such as going lean in healthcare,68 engaging physicians in a shared quality agenda,42 transforming care at the bedside,69 and improving the reliability of healthcare.70

Finally, numerous resources are available from a number of professional organizations and societies to assist in developing strategies and plans for selection, implementation, and use of HIT and EHR systems to improve quality and achieve MU. For example, the Health Information and Management Systems Society (HIMSS) offers useful conferences, educational programs, information, and resources in a wide variety of areas spanning the spectrum of healthcare reform, EHR systems, clinical informatics, IT privacy and security, interoperability, IT standards, ambulatory information systems, and financial systems.71 Likewise, the American Medical Informatics Association (AMIA)72 provides programs and resources to support the effectiveness of healthcare industry professionals in using information and IT to support patient care, public health, teaching, research, administration, and related policy. Specialty societies have also made useful resources for EHR selection, implementation, and MU available, such as the Center for Practice Improvement and Innovation at the American College of Physicians73 and the Center for Health IT at the American Academy of Family Physicians.74

Information Technology Strategies to Use Gains from Meaningful Use to Improve Quality and Value

Once the hospital or office practice leadership has shaped its culture and systems so that physicians and staff can be counted on to use clinical information systems regularly and appropriately, the next issue is to determine the HIT and EHR features and functionalities that are necessary or desirable, not only for MU, but also to support other quality initiatives, practice improvement activities, resource use, and readiness to participate in alternative payment models. As explicit CMS incentive payments for MU sunset and MU become an important but more integral part of consolidated incentive payments for outcomes, EPs, EHs, and CAHs will need to continue to ensure that they have the CEHRT in place and in regular use to meet the goals, objectives, and measures developed by the Health IT Policy Committee as part of the ARRA and HITECH Act, such as the current objectives and measures listed for EPs for MU Stage 2,75 but it is important to be mindful that these are likely to be updated for 2015–2017.35 Recognizing that the details and thresholds for specific objectives are in flux, we outline strategies for achieving these MU goals, objectives, and reporting requirements, which we believe will be relevant regardless of the details of the final objectives and measures. Also, rather than detailing the differences between provider and hospital objectives and measures, we will emphasize the system features and functionalities that need to be in place and used to qualify for MU and to be ready for future payment models. Note also that in the lists to follow, we use an asterisk (*) to signify that an item is no longer a separately reported measure but required as part of another measure. In addition, we have italicized items that have been proposed for removal for 2015–2017.35

Policy Priority 1: Improve Quality, Safety, Efficiency, and Reduce Health Disparities

The care goals for this health outcomes policy priority are to (1) provide the patient’s care team with access to comprehensive patient health data, (2) use evidence-based orders sets and computerized provider order entry (CPOE), (3) apply clinical decision support (CDS) at the point of care, (4) generate lists of patients who need care and use the lists to reach out to patients, and (5) report to patient registries for quality improvement and public reporting. The objectives include expectations for electronically capturing in coded format information to allow tracking and reporting on key clinical conditions. To that end and for each patient, qualifying providers and hospitals will be expected to:

• Use CPOE for medication, imaging, and laboratory orders

• Implement drug–drug, drug–allergy, and drug–formulary checks

• *Maintain a current problem list

• Use electronic prescribing for permissible prescriptions

• *Maintain an active medication list

• *Maintain an active medication allergy list

• Record demographics (race, ethnicity, gender, insurance type, primary language)

• Record advance directives (hospitals only)

• Record vital signs (height, weight, blood pressure)

• Calculate and display body mass index (BMI)

• Record smoking status

• Incorporate laboratory/test results into EHR as structured data

• Generate lists of patients by specific conditions

• *Report quality measures to CMS

• Send patients reminders per patient preference for preventive/follow-up care

• Implement five clinical decision support rules related to four or more clinical quality measures, relevant to specialty or high clinical priority

• Document progress note for each office encounter

Electronically capturing these data in a structured format is critical to ensuring that the EHR database contains the necessary information for reporting quality measures to CMS, such as the percentage of:

• Diabetics with A1c under control

• Hypertensive patients with blood pressure under control

• Patients with low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol under control

• Smokers offered smoking cessation counseling

• Patients with a recorded body mass index (BMI)

• Orders entered directly by licensed healthcare professionals through CPOE

• Patients older than age 65 receiving high-risk medications

• Patients older than age 50 with colorectal cancer screening

• Female patients older than age 50 receiving an annual mammogram

• Patients at high risk for cardiac events on aspirin prophylaxis

• Patients receiving flu vaccine

• Percent of lab results incorporated into EHR in coded format

• Medications entered into EHR as generic when generic options exist in the relevant drug class

• Orders for high-cost imaging services with specific structured indications recorded

• Claims admitted electronically to all payers

• Patient encounters with insurance eligibility confirmed

To meet the Stage 2 objectives and report the measures, we recommend the following EHR functionalities (supported by a practice management system or third-party vendor solutions where relevant) be installed and operational:

• Structured data entry mechanisms acceptable to users for entering patient demographics, advance directives, orders, problems, medications, allergies, vital signs, relevant history (e.g., smoking status), and interventions (e.g., smoking cessation counseling)

• Functioning interfaces from the laboratory and radiology information systems to the EHR for receiving results

• E-prescribing capability that includes drug–drug, drug–allergy, and drug–formulary checks

• Clinical decision support functionality (calculating and displaying BMI, creating clinical decision rules)

• Registry functionality with actionable views and communication tools (secure messaging for reminders)

• EHR data mining and reporting tools

Policy Priority 2: Engage Patients and Families

The care goal for this health outcomes policy priority is to provide patients and families with timely access to data, knowledge, and tools to make informed decisions and to manage their health. To demonstrate MU in Stage 2, providers and hospitals will be expected to:

• Provide patients access to view, download, or transmit health information

• Use information stored in CEHRT to identify and provide patient-specific educational materials

• Provide patients with a clinical visit summary for each encounter

• Implement a mechanism for patients to send secure messages to the EP’s practice

Assessing the degree of patient and family engagement will entail reporting the following Stage 2 measures to CMS, including the percentage of:

• Patients who have access to view, download, or transmit health information, as well as patients who actually do so

• Patients who are provided with or who have access to patientspecific educational resources identified by CEHRT

• Encounters where a clinical visit summary was provided

• Patients with patient-initiated secure messages sent to the EP’s practice

To meet the Stage 2 patient and family engagement objectives and report the measures, we recommend the following functionalities be installed and operational:

• EHR-supported workflows that result in capture of relevant information to populate the clinical encounter

• the ability at the point of care to electronically transmit educational materials to the patient from within usual EHR workflows (e.g., electronically send to the patient portal rather than print handouts)

• A secure, EHR-linked patient Web portal with the capability to support selective EHR chart views (e.g., problem list, medication list, allergies, lab results), secure messaging, conditionspecific educational resources, encounter summaries, and an option for the patient to have a personal health record (PHR)

Policy Priority 3: Improve Care Coordination

The care goal for this health outcomes policy priority is to exchange meaningful clinical information among professional healthcare teams. the Stage 2 objectives for care coordination are to:

• Send summary of care records with transitions out to other providers, with a threshold for electronic exchanges using specified mechanisms (e.g., Direct Protocol)

• Perform medication reconciliation at transitions of care into the care of the EP, EH, or CAH

The care coordination reporting requirements for Stage 2 include the following:

• Percent of encounters where medication reconciliation was performed

• Percent of outbound care transitions where a summary of care record is sent by any modality, and the percent sent electronically

To meet the Stage 2 care coordination objectives and report the measures, we recommend the following functionalities be installed and operational:

• An EHR-integrated secure clinical messaging solution that includes Direct Protocol functionality and allows secure sending and receipt of consolidated clinical document architecture (CCDA) formatted clinical summaries, messages, and electronic chart documents to other patient-authorized entities, whether or not the external entity has an EHR system in place

• An audit system to record and report instances of exchange of health information, including summary of care records shared, as well as the context in which they occur (e.g., admission, discharge, transfer, referral, follow-up)

• Medication reconciliation functionality that allows for recording of medication changes between visits and at transitions of care, as well as incorporating evidence of fill history to capture medications prescribed but not filled and medications added or changed by other providers

Policy Priority 4: Improve Population and Public Health

The goal of this health outcomes policy priority is communication with public health agencies. The Stage 2 objectives for improving population and public health are to:

• Submit electronic data to immunization registries where required and accepted (EPs)

• Submit electronic syndrome surveillance data to public health agencies according to applicable law and practice (EHs)

The population and public health reporting requirements for Stage 2 include the following:

• Report up-to-date status of childhood immunizations

• Percent of reportable laboratory results submitted electronically

To meet the Stage 2 population and public health objectives and report the measures to CMS, we recommend the following EHR functionalities be installed and operational:

• Immunization recording tools that capture all relevant immunization data in a structured manner to support reporting to state immunization registries and CMS

• An interface from the EHR to the external immunization registry in regions where actual submission of immunization information is required and can be accepted

• Auditing tools for reporting on all structured data (e.g., lab results) submitted electronically to public health entities

Policy Priority 5: Ensure Adequate Privacy and Security Protections for Personal Health Information

This health outcomes policy priority seeks to ensure privacy and security protections for confidential information through operating policies, procedures, and technologies and compliance with applicable law. It also works toward the goal of providing transparency of data sharing to patients. The Stage 2 objectives for privacy and security protections include the following:

• Compliance with HIPAA privacy and security rules

• Compliance with fair data sharing practices set forth in the national privacy and security framework76

The privacy and security protections reporting requirements for Stage 2 are to:

• Demonstrate full compliance with the HIPAA privacy and security rule77

• Conduct or update a security risk assessment and implement security updates as necessary

To meet the Stage 2 privacy and security protection objectives and report the measures to CMS, we recommend the usual organizational IT technical approaches for safeguarding patient information (e.g., firewalls, virtual private networks, intranets, data encryption (including encryption of data at rest), prevention of protected health information (PHI) data storage on local devices, strong authentication) and strong organizational policies and procedures for identity proofing, user authentication, and authorization, as well as for preventing, detecting, and taking action on instances of suspected breaches in patient data privacy, confidentiality, and security. In addition, we recommend the following EHR functionalities be installed and operational:

• EHR system configuration to support strong user authentication and role-based privileges

• Use of EHR functionalities to “hide” information that a particular user is not authorized to view under any circumstances (e.g., highly confidential documents, sensitive charts)

• Activation of “break the glass” tools (where appropriate) to warn users in advance of potentially unauthorized chart or information access, with options to record a reason for seeking access (e.g., emergency), enhanced auditing of those who proceed, and additional scrutiny of those who do not

• Activation of auditing tools to enable tracking of all relevant details of EHR system access, chart access, patient data and document viewing, modification, deletion, storage, printing, and transmission

• Ability to facilitate delivery and electronically record delivery of privacy practices notices to individual patients

• Creation of automated reports using filters that have a high signal-to-noise ratio, creating a short list of individuals that are highly likely to have accessed patient data inappropriately, rather than a long list of individuals, most of whom accessed charts appropriately

Meaningful Use: The Road Ahead

This chapter was written during a period of great flux in the MU and EHR certification programs. Three proposed rules were finalized, including: (1) electronic health record incentive program modifications to MU in 2015 through 201735; (2) the CMS MU Stage 3 proposed rule,36 and the ONC 2015 Edition HIT certification criteria, base EHR definition, and HIT certification program modifications.37 While the full implications of these Final Rules will be revealed over the next several years, it is clear that HHS, CMS, and ONC have employed various regulatory and policy levers to drive interoperability, simplify and synchronize the MU program, align MU reporting periods, improve various aspects of clinical quality measurement and reporting, focus on clinically relevant outcomes, and promote alternative health models and alternative payment systems. While CMS has announced that it intends Stage 3 to be the final stage of the MU incentive program, inclusion of MU as one of the four performance categories of MACRA ensures that the objectives and measures included in the Stage 3 Final Rule will continue to drive how CEHRT is used to advance the overarching goals of the HITECH Act and MU program.

Although the details of the Stage 3 program may change further as CMS weighs the comments it received following publication of the Final Rule and incorporates the Meaningful Use program into the Merit-Based Incentive Payment System (MIPS), EPs, EHs, and CAHs can anticipate following:

• By 2018, everyone will be on the same stage of MU (Stage 3), regardless of how long they have been in the program.

• There will be only one set of objectives, measures, and thresholds.

• All MU participants will be required to use 2015 Edition CEHRT.

• Everyone will have the same calendar year reporting period (with the possible exception of Medicaid Year 1 EPs).

• MU quality measure reporting will be simplified by alignment with other quality measure programs, such as the Physician Quality Reporting System (PQRS) and Hospital Inpatient Quality Reporting (IQR).

• Quality measures will not be proposed in the MU reporting program itself. Instead, quality measures will be incorporated annually in the Inpatient Prospective Payment System (IPPS) and Physician Fee Schedule (PFS) rules where Hospital IQR and PQRS are defined.

• Electronic submission of Clinical Quality Measures (eCQMs) will be required (with some exceptions).

• A number of measures will be removed for individual reporting because they were deemed to be topped out, redundant, or duplicative.

MU will focus on eight objectives, several of which have multiple measures that must be reported but not all will require exceeding the threshold:

1. Protect Patient Health Information

2. Electronic Prescribing

3. Clinical Decision Support

4. CPOE

5. Patient Electronic Access to Health Information

6. Coordination of Care through Patient Engagement

7. Health Information Exchange (HIE)

8. Public Health and Clinical Data Registry Reporting

EPs, EHs, and CAHs will do well to continue to focus on leveraging HIT to capture and share data, advance clinical processes, and improve patient outcomes. They will benefit from expanding their use of CPOE and evidence-based order sets, focusing their EHR clinical documentation in a manner that facilitates identifying and closing gaps in care, e-prescribing discharge medications, managing chronic conditions using patient lists and population health management tools, utilizing robust clinical decision support at the point of care, having specialists report data to external registries, and implementing closed-loop medication management, including electronic medication administration records and computer-assisted medication administration.

As engaging patients in their own care can facilitate goals for quality and value, health professionals and organizations will benefit from providing access for all patients to a personal health record, a patient Web portal populated with health data in real time, or APIs offering secure patient–provider messaging capability, providing patient-specific educational resources in common primary languages, recording patient preferences, documenting family medical history, and uploading data from home monitoring devices. Care coordination will benefit from being able to retrieve and act on electronic prescription fill data, production and sharing of an electronic summary care record for every transition of care, and medication reconciliation at each transition of care from one health setting to another.

Continued engagement around population and public health objectives will facilitate bidirectional exchange of immunization histories and recommendations from immunization registries, receiving health alerts from public health agencies, and providing sufficiently anonymized electronic syndrome surveillance data to public health agencies with the capacity to link to personal identifiers. Privacy and security protection will become increasingly challenging in this time of increasingly sophisticate cyberattacks, and must be balanced with the need to access PHI for clinical care and the generation of summarized or de-identified data when reporting data for population health purposes.

To drive quality and value from today into the future, providers and hospitals should be routinely using CDS for national high-priority conditions, achieve medical device integration, and deploy multimedia support for imaging technology. Patients should have access to online self-management tools, be able to complete online health questionnaires, upload data from home health devices, and report electronically on their experiences of care. Health information exchanges of various types should facilitate access to comprehensive patient data from all available and appropriate sources; enable use of epidemiologic data in clinical decision making; and allow for automated real-time surveillance for adverse events, near misses, disease outbreaks, and bioterrorism. Clinical dashboards and dynamic and ad hoc quality reports should also be routinely available. Privacy and security goals include providing patients with an accounting of treatment, payment, and healthcare operations disclosures on request, as well as minimizing the reluctance of patients to seek care because of privacy concerns.

In closing, we are reminded once again that our healthcare iceberg is melting. For all the risks associated with change and all of the unintended consequences of the MU incentive program, failing to adopt and meaningfully use EHR systems risks leaving our patients behind, while the healthcare system they depend on and those who financially support it strain under the weight of inconsistent quality, excessive waste, and unsustainable cost increases. Though imperfect, we see the MU incentive program and the various federal agencies promoting the safe and effective use of HIT as powerful catalysts for needed change. We also see provider payment reform as reflected in MACRA as necessary for durable change, by transitioning a significant fraction of payment away from volume and procedures and instead rewarding HIT–powered improvements in quality, value, and outcomes. Although EHR systems are also far from where they need to be to optimally support effectiveness, efficiency, interoperability, safety, and health information exchange, many are good enough to make continued striving to implement and use them reasonable and worth including in incentive programs going forward. It’s “quality time”—time to keep moving on the journey to transform care.

References

1. Kotter J, Rathgeber H. 2006. Our iceberg is melting: Changing and succeeding under any conditions. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

2. Kotter J. 1996. Leading change. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

3. Park T, Basch P. 2009. Wedding health information technology to care delivery innovation and provider payment reform. Washington, DC. Available at: http://www.americanprogress.org/issues/2009/05/health_it.html.

4. Nance J. 2008. Why hospitals should fly—The ultimate flight plan to patient safety and quality care. Bozeman, MT: Second River Healthcare Press.

5. Health expenditure per capita (current US$). The World Bank, 2015. Available at: http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.XPD.PCAP.

6. Health expenditure, total (% of GDP). The World Bank, 2015. Available at: http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.XPD.TOTL.ZS.

7. O’Neill P.H. 2006. Testimony in hearings before the Senate Committee on Commerce. Senate Committee on Commerce. 109th Congress, 2nd session. Washington, DC.

8. Milstein A. 2004. Testimony in hearings before the Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pension. Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pension. 108th Congress, 2nd session. Washington, DC.

9. PricewaterhouseCoopers Health Research Institute. 2008. The price of excess: Identifying waste in healthcare spending. Dallas: Pricewaterhouse Coopers.

10. Ginsburg JA, Doherty RB, Ralston JF Jr, Senkeeto N, Cooke M, Cutler C et al. 2008. Achieving a high-performance health care system with universal access: What the United States can learn from other countries. Ann Intern Med 148:55–75.

11. Smith JC, Medalia C. Health Insurance in the United States: 2013. U.S. Department of Commerce, Economics and Statistics Administration, U.S. Census Bureau. Available at: http://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2014/demo/p60-250.pdf.

12. Brotherton SE, Etzel SI. 2008. Graduate medical education, 2007–2008. Jama 300:1228–1243.

13. Kaiser Family Foundation. 2009. Medicare beneficiaries and the number of workers per beneficiary. Menlo Park, CA: Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation.

14. Fisher ES, Wennberg DE, Stukel TA, Gottlieb DJ, Lucas FL, Pinder EL. 2003. The implications of regional variations in Medicare spending. Part 2. Health outcomes and satisfaction with care. Ann Intern Med 138:288–298.

15. Fisher ES, Wennberg DE, Stukel TA, Gottlieb DJ, Lucas FL, Pinder EL. 2003. The implications of regional variations in Medicare spending. Part 1. The content, quality, and accessibility of care. Ann Intern Med 138:273–287.

16. Baicker K, Chandra A. 2004. Medicare spending, the physician workforce, and beneficiaries’ quality of care. Health Aff (Millwood) Suppl Web Exclusives W184–197.

17. Gawande A. 2009. The cost conundrum. The New Yorker, June 1.

18. Zerehi MR. 2008. How is the shortage of primary care physicians affecting the quality and cost of medical care? Philadelphia: American College of Physicians. White Paper.

19. O’Malley AS, Forrest CB. 2006. Immunization disparities in older Americans: Determinants and future research needs. Am J Prev Med 31:150–158.

20. Lewis CE, Clancy C, Leake B, Schwartz JS. 1991. The counseling practices of internists. Ann Intern Med 114:54–58.

21. Macinko J, Starfield B, Shi L. 2003. The contribution of primary care systems to health outcomes within Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries, 1970–1998. Health Serv Res 38:831–865.

22. Carey TS, Garrett J, Jackman A, McLaughlin C, Fryer J, Smucker DR. 1995. The outcomes and costs of care for acute low back pain among patients seen by primary care practitioners, chiropractors, and orthopedic surgeons. The North Carolina Back Pain Project. N Engl J Med 333:913–917.

23. Greenfield S, Rogers W, Mangotich M, Carney MF, Tarlov AR. 1995. Outcomes of patients with hypertension and non-insulin dependent diabetes mellitus treated by different systems and specialties. Results from the medical outcomes study. Jama 274:1436–1444.

24. How SKH, Shih A, Lau J, Schoen C. 2008. Public views on U.S. health system organization: A call for new directions, The Commonwealth Fund, 11:1–15.

25. Kohn L, Corrigan, J, Donaldson, MS, eds. 2000. To err is human: Building a safer health system. Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

26. Committee on Quality Health Care in America IOM. 2001. Crossing the quality chasm: A new health system for the 21st century. Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

27. Dick RS, Steen EB, Detmer DE, eds. 1997. The computer-based patient record: An essential technology for health care. Rev. ed. Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

28. Hillestad R, Bigelow J, Bower A, Girosi F, Meili R, Scoville R et al. 2005. Can electronic medical record systems transform health care? Potential health benefits, savings, and costs. Health Aff (Millwood) 24:1103–1117.

29. Walker J, Pan E, Johnston D, Adler-Milstein J, Bates DW, Middleton B. 2005. The value of health care information exchange and interoperability. Health Aff (Millwood).

30. Girosi F, Meili R, Scoville R. 2005. Extrapolating evidence of health information technology and costs. Santa Monica, CA: Rand Corporation.

31. Chaudhry B, Wang J, Wu S, Maglione M, Mojica W, Roth E et al. 2006. Systematic review: Impact of health information technology on quality, efficiency, and costs of medical care. Ann Intern Med 144:742–752.

32. Halamka JD. 2006. Health information technology: Shall we wait for the evidence? Ann Intern Med 144:775–776.

33. American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009. In: 111 ed. USA, p. 407. Available at: http://healthit.hhs.gov/portal/server.pt?open=512&objID=1325&parentname=CommunityPage&parentid=1&mode=2.

34. Health Information Technology Federal Advisory Committees. 2009. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

35. Medicare and Medicaid Programs; Electronic Health Record Incentive Program-Modifications to Meaningful Use in 2015 Through 2017. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, April 15, 2015. Available at: https://federalregister.gov/a/2015-08514.

36. Medicare and Medicaid Programs; Electronic Health Record Incentive Program-Stage 3 and Modifications to Meaningful Use in 2015 Through 2017. Available at: https://www.federalregister.gov/articles/2015/10/16/2015-25595/medicare-and-medicaid-programs-electronic-health-record-incentive-program-stage-3-and-modifications.

37. 2015 Edition Health Information Technology (Health IT) Certification Criteria, 2015 Edition Base Electronic Health Record (EHR) Definition, and ONC Health IT Certification Program Modifications March 30, 2015. Available at: https://federalregister.gov/a/2015-06612.

38. Better, Smarter, Healthier: In historic announcement, HHS sets clear goals and timeline for shifting Medicare reimbursements from volume to value. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. January 26, 2015. Available at: http://www.hhs.gov/news/press/2015pres/01/20150126a.html.

39. H.R.2—Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015. Public Law No: 114-10 (04/16/2015), US Library of Congress. Available at: https://www.congress.gov/bill/114th-congress/house-bill/2/text.

40. HIMSS Fact Sheet: Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015 (MACRA). Health Information and Management Systems Society, April 23, 2015. Available at: http://www.himss.org/ResourceLibrary/genResourceDetailPDF.aspx?ItemNumber=41882.

41. Meaningful use. 2009. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Available at: http://healthit.hhs.gov/portal/server.pt?open=512&objID=1325&parentname=CommunityPage&parentid=1&mode=2.

42. Reinertsen JL, Gosfield AG, Rupp W, Whittington JW. 2007. Engaging physicians in a shared quality agenda. IHI Innovation Series white paper. Cambridge, MA: Institute for Healthcare Improvement.

43. Zaroukian MH, Sierra A. 2006. Benefiting from ambulatory EHR implementation: Solidarity, Six Sigma, and willingness to strive. J Healthcare Inf Manag 20:53–60.

44. Health information technology donations: A guide for physicians. 2008. Chicago.

45. Rucker DW, Steele AW, Douglas IS, Coudere CA, Hardel GG. 2006. Design and use of a joint order vocabulary knowledge representation tier in a multi-tier CPOE architecture. AMIA Annu Symp Proc 2006:669–673.

46. Ash JS, Berg M, Coiera E. 2004. Some unintended consequences of information technology in health care: The nature of patient care information system-related errors. J Am Med Assoc 11:104–112.

47. Ash JS, Sittig DF, Poon EG, Guappone K, Campbell E, Dykstra RH. 2007. The extent and importance of unintended consequences related to computerized provider order entry. J Am Med Inform Assoc 14(4):415–423.

48. Koppel R, Wetterneck T, Telles JL, Karsh BT. 2008. Workarounds to barcode medication administration systems: Their occurrences, causes, and threats to patient safety. J Am Med Inform Assoc 15:408–423.

49. Koppel R, Leonard CE, Localio AR, Cohen A, Auten R, Strom BL. 2008. Identifying and quantifying medication errors: Evaluation of rapidly discontinued medication orders submitted to a computerized physician order entry system. J Am Med Inform Assoc 15:461–465.

50. Harrison MI, Koppel R, Bar-Lev S. 2007. Unintended consequences of information technologies in health care—An interactive sociotechnical analysis. J Am Med Inform Assoc 14:542–549.

51. Koppel R, Metlay JP, Cohen A, Abaluck B, Localio AR, Kimmel SE et al. 2005. Role of computerized physician order entry systems in facilitating medication errors. Jama 293:1197–1203.

52. Koppel R. 2005. What do we know about medication errors made via a CPOE system versus those made via handwritten orders? Crit Care 9:427–428.

53. Miller RH, Sim I, Newman J. 2004. Electronic medical records in solo/small groups: A qualitative study of physician user types. Medinfo 2004:658–662.

54. Rogers EM. 2003. Diffusion of innovations. 5th ed. New York: Free Press.

55. Batalden P. 1984. Every system is perfectly designed to get the results it gets. Available at: www.dartmouth.edu/~cecs/hcild/hcild.html.

56. Berwick DM, Nolan TW, Whittington J. 2008. The triple aim: Care, health, and cost. Health Aff (Millwood) 27:759–769.

57. Godfrey MM, Nelson EC, Batalden PB. 2004. Assessing your practice: The green book. Dartmouth College, Institute for Healthcare Improvement.

58. Godfrey MM, Nelson EC, Batalden PB. 2005. Assessing, diagnosing and treating your inpatient unit. In Clinical microsystems greenbooks. 2nd ed. Hanover, NH: Dartmouth College.

59. Godfrey MM, Nelson EC, Batalden PB. 2005. Assessing, diagnosing and treating your outpatient specialty care practice. In Clinical microsystems greenbooks. 2nd ed. Hanover, NH: Dartmouth College.

60. Murray M, Tantau C, eds. 2002. Improving patient access to care—Primary care. 2nd ed. Lebanon, NH: Trustees of Dartmouth College.

61. Clinical microsystems. Hanover, NH: Dartmouth College.

62. Johnson JK. 2003. Clinical microsystem assessment tool. 2nd ed. Lebanon, NH: Dartmouth College. Available at: http://dms.dartmouth.edu/cms.

63. Godfrey MM, Nelson EC, Batalden PB, Wasson JH, Mohr JJ, Huber T et al. 2004. Clinical microsystem action guide. 2nd ed. Hanover, NH: Dartmouth College.

64. IHI.org. A resource from the Institute for Healthcare Improvement. Cambridge, MA: Institute for Healthcare Improvement.

65. IHI.org. Improvement methods. Cambridge, MA: Institute for Healthcare Improvement.

66. 10th Annual International Summit on Redesigning the Clinical Office Practice. 2009. Cambridge, MA: Institute for Healthcare Improvement.

67. IHI.org. White papers. Cambridge, MA: Institute for Healthcare Improvement.

68. Institute for Healthcare Improvement. 2005. Going lean in health care. Cambridge, MA: Institute for Healthcare Improvement.