10 GETTING THERE – DEVELOPING A PLAN

You will now have run a need-gap analysis and identified where the current IT governance activities are weak, and you will have developed a charter providing a list of expectations of the business from IT and expectations of IT delivery from the business. You will have a clear view of where the organisation is going in a strategic sense, and the overall organisational culture and appetite for risk and change. You will have identified the key people in the organisation who will champion new ways of working, and you will have certainly identified the people who will attempt to block your progress (consciously or unconsciously). By now you will be having regular debriefs with your organisational sponsor, and you will be putting together a team to develop and implement an IT governance plan.

Your IT governance champions will be invaluable as they will promulgate new processes in their own group. Your blockers are also a surprisingly useful resource as they will be the first to identify why your new process will not work. Often the blockers are staff who feel threatened by formalised process – and there are several possible causes. They could be the organisational heroes who fire fight their way out of problems when IT systems go down. There will be those that feel that a sound decision-making process for IT acquisitions will curb their freedom, or maybe even stop some of their current activities. There will also be the cynics and sceptics who have been in the organisation since time began and have lived through a number of unsuccessful attempts to formalise process. If IT has previously been the ‘Cinderella’ of the organisation, and it looks as though it will have a sudden meteoric rise in organisational importance, then there will be a political power battle breaking out around you. This is all to be expected. The worst case scenario is when no resistance is observed. Apathy is your worst enemy, as it comes with no associated energy for discussion or debate.

For the project itself to be successful, you need a good, enthusiastic and able team and a strong sponsor who can go into bat for resources and who can drive a sense of urgency around the project. For the principles of IT governance to be fully adopted and wound into the overall organisational governance, you need ‘buy-in’ from the senior executives and a champion or two on the board of directors or governing body. You will have already set this process in motion by interviewing the board member responsible for IT, but for the ongoing work to be successful, you need to formalise the link between the project and the board. This could be in the form of regular updates to the board, or the establishment of a subcommittee to have oversight of the project deliverables.

BENEFITS OF THE MODULAR APPROACH

Another consideration before embarking on the plan itself is the timeline for getting an IT governance framework in place – and this will depend on the key drivers behind the project. If you are looking at a short time frame to get the full framework in place, then you will be faced with a big-bang implementation, where you will be turning on policy, process and procedure across the organisation and expecting staff to go to sleep with one system in place and to wake up ready to use a totally new system.

One of the hardest things to deal to with when using the big-bang approach is training. Most likely you are driven by a legislative or financial requirement. At first it seems like a grand plan to implement over Christmas, or at the end of the financial year. Christmas is a problem, especially in the southern hemisphere where the Christmas break is the long summer holiday. Training before Christmas, expecting your staff to return fully up to speed in new systems and processes after two weeks on vacation, is wishful thinking. Expecting to make a swift change-over at the end of the financial year without destabilising the CFO and finance department is also wishful thinking. So, unless you are being held at gunpoint to implement a new IT governance framework in one step, I advise a modular approach. There are a number of discrete activities that need to be carried out to build the full framework. Once these have been identified, along with dependencies of one module on another, it will be reasonably straightforward to determine an execution order. You can look at a horizontal or a vertical approach – whichever best suits the organisation. For example, having established a principle of acquisition, you can develop the organisational policies required to meet the principle. Then you can work through the processes and procedures required across the organisation to ensure that the policy is adhered to on every procurement or acquisition. Alternatively, you can work through the acquisition policy requirements with each group across the organisation and pull the requirements together as one organisational policy. Pick the approach that encourages the most support and cooperation of individuals within the organisation. For the project to be a success, you need to have as many people as possible across the organisation aligned to driving positive outcomes.

Whichever policy development path you take, it will often become blindingly obvious as you develop procedure that the policy is ‘wrong’ in some major way. It could be wrong because it is ambiguous or wrong because it drives behaviour that is contrary to the benefit of the organisation. A classic example here is the organisation that decides that acquisitions over a gazillion dollars need to be approved by the senior management and 10 gazillion by the board. Something magic happens overnight – the gazillion dollar projects break into multiple parts, and the multi-gazillion projects fracture into a set of gazillion dollar projects. And, of course, the point of impact is missed completely. An IT project with a budget that can be funded out of the petty cash of the coffee club, to change the colour of the website, can have huge impact. So the lesson here is to develop unambiguous policy and procedures that drive ‘good behaviour’.

EMBEDDING AND COMMUNICATING THE PLAN

One of the keys to embedding new procedures and processes is to identify ‘process champions’ across the organisation who will quickly pick up and embrace new ways of operating and will act as leaders for the people around them. Training is another crucial element. People have different ways of taking in information, so you need to operate several channels of information to reach as many people as possible. The seven learning styles are recognised as visual, aural, verbal, physical, logical, social and solitary. In practice, to be effective, your training programme needs to include visual material, presentations by the project team, paper or online material that the staff can read at their leisure, practical activities and examples involving problem solving, and opportunities to participate in discussion groups. Remember to pay special attention to part-time staff and staff who regularly work away on a client site. They will already feel on the edge of the organisation, so do not isolate them further.

![]()

I was part of a project team years ago implementing a business process improvement programme. Every week our CEO put out an update on the project through his letter to staff – and yet no-one appeared to know what was going on when we met with them. One of the admin staff who did read the CEO letter and did know what was going on was accused of having insider information. It slowly dawned on us as a team that we were not getting through to our target audience. The final straw was when we repeated our communications through a presentation to the all-company meeting and just about everybody looked genuinely surprised. We worked hard to come up with more innovative ways of communicating. We decided that we needed a captive audience and an eye-catching theme for our communications and that drastic action was called for. We started putting up posters in the toilets and, within a week, the project was the talk of the company.

DEVELOPING ARTEFACTS

As IT people, we often talk about road maps and strategic planning when, in fact, a simple to-do list would be adequate. However, in the case of delivering a decision-making framework and the associated policies and procedures, the concept of a road map is very useful. Staff at all levels want to know what impact the project will have on their daily lives. Most would opt to stay with the bad process they understand (the devil they know) rather than have to learn new processes and procedures. And even though you can promise great things for the new framework once it is bedded in, it is highly likely that things will get worse before they get better. There is a curve of despondency and misery associated with most IT projects that looks like a skewed parabola. The lowest point is hit maybe three to six months into the project when the initial enthusiasm has worn off, the members of the project team are tired and not making progress as quickly as they had hoped, the staff are working across two systems and picking holes in the new processes, and the customers are calling in confused. At this point it is essential to have some artefacts that will get the team and the organisation through the difficult patch. Anything you can create that will help the staff understand the new processes and procedures clearly will be very valuable. A road map, plotting the path through transition is also highly desirable. Consideration of the following three questions will assist in developing an approach to completing the transition work:

- How will the new systems interoperate with the old systems (if at all)?

- How quickly will the new systems be fully operational?

- How will the training fit with the transition plan? Who can staff go to for assistance? Who are the process champions?

![]()

Do not underestimate the value of the humble piece of paper. I worked on an IT project to implement a new system for an insurance company, where some of the users of the new system were answering 0800 (free) calls and working to targets of providing information to customers in the shortest time possible. We developed an online help system, using a violet font to make it unmistakable from any other online help utility, and produced a very grand fold-out card pamphlet, with hints and tips, how-tos and FAQs for using the system, that could sit on the desk. Two years later, when the project was refreshed, the online help was updated but it was considered unnecessary to produce a new version of the pamphlet, much to the disappointment of the key users – the call centre staff. The management team was perplexed – thinking that the call centre staff would not have time to look up answers from the card. However, because the card was attractive, the call centre staff had been reading it between calls.

You also need to produce a set of collateral that shows how the elements of the framework fit together, so that staff across the organisation can see that policy is aligned with organisational principles that have been signed off by the board, that process is developed from policy and that the procedures enable the fulfilment of the policies. By doing this, it will become obvious that procedures cannot be changed in isolation, but need to be adjusted in conjunction with policy and process.

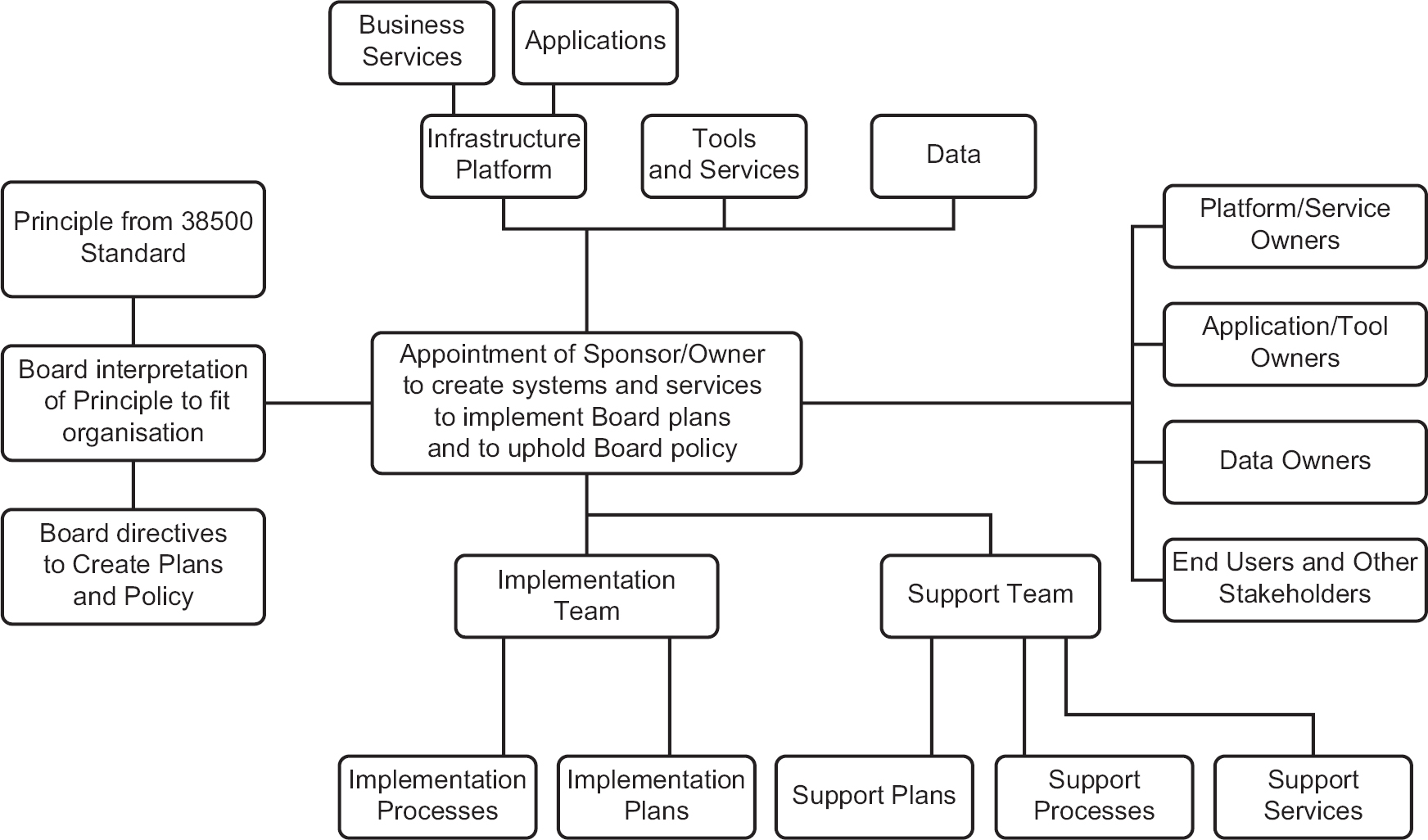

The diagram in Figure 10.1 demonstrates how elements of the governance framework work together.

Also, if the implementation of the IT governance framework has resulted in the establishment of new roles or new responsibilities for existing roles, these need to be carefully communicated. It is most frustrating to request approval for purchase, only to find that the person you sent the request to is no longer responsible for the area. It is best if staff find out about new roles and responsibilities from the CEO than from somebody’s out-of-office message or from the water cooler gossip.

PROJECT PRIORITISATION AGAINST THE PRINCIPLES

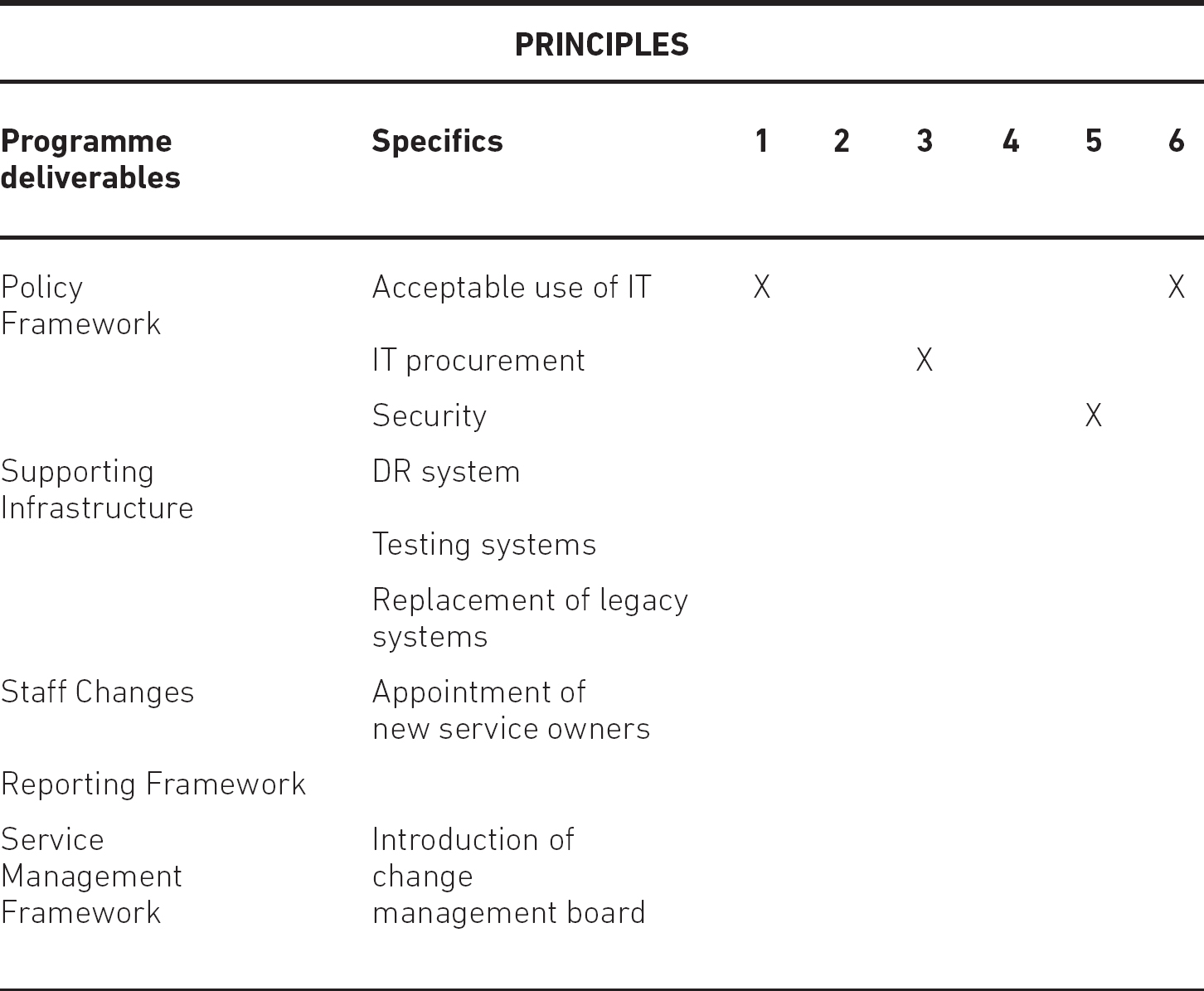

And finally, to help the prioritisation of your projects, map the key deliverables from each project against the six principles in such a way that you capture the risk of not doing the piece of work and the impact of completing the work. The resulting table will provide a good indicator for what should be completed in what order. Deliverables that have impact across all principles are likely to be your highest priority. However, if the organisation is going through a high growth or a crisis situation, it would be wise to put a greater weighting on the principle that is most relevant. This will ensure that the IT team will deliver the requirements based on organisational need.

Figure 10.1 Framework detail example

Table 10.1 shows how you can start mapping programme deliverables to the six principles. Some of the deliverables will align to more than one principle. If you mark the key principle, then it will help guide your reporting. Deliverables that align to more than one principle will be more complex to deliver.

Table 10.1 Mapping programme deliverables to the six principles

REVIEWING THE ORGANISATIONAL CHART AND BUILDING YOUR TEAMS

As you develop your plan, you will be looking to the organisational chart to build your project teams and to build an operational team to take delivery of programme outputs. You will be looking for leaders and ensuring that they have the capability, responsibility and authority to enable them to take on the tasks ahead. First, you need to review the corporate culture and the perceived value of IT across the organisation, as this will help you determine who will be the right fit for each role. Does your organisation put a strong emphasis on hierarchy? In general are your staff members competitive? Are your staff highly networked? Do they socialise together? What is the most common demographic of your staff members?

Answering the following questions will help you determine who to put where:

- Who are your capable leaders?

- Who are your honest and direct members of staff?

- Who are your highly networked members of staff?

- Who are the staff who find problems everywhere?

- Who are your destructive members of staff?

- Who are your fastidiously tidy and careful staff members?

- Who are the rumour-mongers?

- Where are the conflicts of interest?

When building your teams, you need to ensure that your members are capable and equipped to do the role set before them. Depending on your organisational culture, you will choose different personality types for different roles and teams. For example, if your organisation is very people-focused and the vision and mission are centred on helping or assisting people in some way, then your trainers need to be highly networked people. Training can be a bit ad hoc, as long as it is sociable. If your organisation is very process-oriented, and your vision and mission are centred on achieving goals, then your trainers need to be detail- and process-focused. Training must be regimented and trainers need to stick to their allotted time slots. And, whatever your organisation type, your destructive members of staff and the ones who find problems everywhere will make excellent framework testers. Your team leaders need to represent the personality strengths of their group, have some influence across the organisation and the respect of the team members that they are leading.

The following questions around capability and responsibility will help you review your team structure:

- Do the project role names align with the staff job descriptions and KPIs? Generally, people are pulled onto a project team whilst retaining their original role. At stages of the project where the project role expands, it is wise to backfill the original role. It makes sense to have new job descriptions and KPIs for the staff in their project role. Otherwise, it is possible for staff to be seconded to a project for a year and at the end of the year they have not met their original job KPIs – and they feel as though they have moved backwards career-wise.

- For each individual staff member, does their job description match with their skill set and formal qualifications and training as outlined in their CV?

- For each staff member under consideration, are they better suited to a project role or to an operational role?

- Are you missing any key roles, where key roles are the ones that you cannot function without? To check that you have everybody you need, do a worked example with one of the key outputs, where you personally have to pick up the tasks that your team will not have the time/capability/geographic reach to do, and it will soon become obvious whether you have omitted one of the key support service roles.

Responsibility

For your team to function efficiently, responsibility needs to be assigned hand-in-hand with authority. Authority without responsibility creates a headache for the manager who cannot guarantee the delivery of KPIs, and responsibility without authority is a headache and a continual source of frustration for the team member who does not have the power to deliver their role. The following questions will help you assign responsibility to your team:

- Have you assigned authority to those who have responsibility to complete tasks and functions?

- Do they have access to sufficient resources (money and staff) to complete these tasks?

- Do your staff have everything they need to complete the tasks set before them?

Reporting lines

Now make sure that all your reporting lines are clear and that you do not have parallel lines or multiple managers per staff member.

- Are any of your teams in competition with each other? It is easy to set up the team that will deliver the ‘new world’, made up of the elite of the organisation, in such a way that the team who are left behind to manage and maintain the ‘old world’ feel like second class citizens. Early antagonism can turn into full scale jealousy and reluctance to assist the new team, if not managed well. To avoid this situation, treat all your teams as equals from the start of the implementation programme.

- Are any of your teams isolated? Though it might seem like a good idea to house your team away from their colleagues, they could become isolated. The team members will not be on project work for ever. If you intend to return them to their originating teams at the end of the project, make sure they do not lose touch with them during the life of the project. It is hard enough to return to an old role after a secondment, without the feeling that your colleagues have moved on without you.

Also, beware of housing all your business analysts or all your enterprise architects together. Your different roles need to mingle together. If they work in isolation as a group, they are likely to deliver solutions that will not work across the organisation.

- Are there any hierarchical or office culture issues? Is part of your team regarded as an organisational overhead? For example, in a consulting organisation where staff are sold out at hourly rates and everyone is aware of cost centres and profit centres, the IT team can be seen as an overhead rather than as an essential supporting service provider.

Team culture

Once you have your teams in place, you want to start building the team culture and setting expectations. You will need to put in place guidelines and policy for your project and your operational teams. For example, you might want to consider a ‘whistle blower policy’ before you embark on your programme. You really want to encourage your teams to report things that they see that are not right. In IT, the lowliest technician or operator can have visibility of corporate information that even your senior managers cannot see. So, what happens if your technician is servicing the CEO’s PC and discovers a disk full of downloaded pornography?

An administrator is reviewing a database and, in error, he deletes a huge chunk of live customer data. He is desperately tired – he has been working long hours on another project. Do you want him to self-report his error? If so, what should happen next when he does?

I am not going to suggest answers to the above questions, but I do suggest that you need to work through these hypothetical examples, and associated questions that are relevant for your organisation, so that you can draw up your whistle blower policy before you need to enforce it. Be aware that, if self-reporting results in disciplinary action, you can be assured that nobody will ever self-report again.

REPORTING ON RISK

Most major IT projects or programmes of work will fall under the oversight of one of the subcommittees of the board or governing body. In most countries where a Western management style is adopted, it is common for an audit and risk committee to have this oversight – a committee whose main aim is to monitor compliance and reduce risk year-on-year. To align your reporting to your target audience, it will help if you can identify some KRIs that you can monitor along your journey. If there is no committee, then responsibility falls to one of the members of the governing body. It is usual for the responsibility to be lumped with financial responsibility. In the case of responsibility being held by an audit and risk committee, reporting needs to focus on the risk profile and compliance. In the case of responsibility being held by one member of the governing body, reporting needs to be focused on portfolio area covered by this member.

Keep the list ‘big picture’ and do not beat yourself up if you did not predict a risk that nobody expected. Be clear to distinguish risk from certainty. If Joe is retiring halfway through the project and Joe is a key stakeholder, ‘Joe retiring’ is not a risk, but ‘losing corporate knowledge when Joe retires’ could be a risk.

From an audit and risk committee point of view, the risks they will be interested in will be the ones that would stop you delivering on time and on budget, the risks that would affect the operation, reputation and financial health of the organisation, and the risks that you would fail to meet the benefits that are expected from the delivery of the project. If you start with these and think through your mitigations and workarounds should anything go wrong, you will be in a good state of preparedness for the project.