1 HISTORY OF CORPORATE GOVERNANCE

I believe that, before you can fully appreciate the need for the corporate governance of IT, you need to have an appreciation of corporate governance. There is often confusion around what is meant by corporate governance, and I have heard colleagues talk about organisations where ‘no corporate governance is in place’. However, if the organisation is running well, making a profit – or at least not making a loss and meeting compliance requirements in the way of tax and other legal obligations – then it must surely have some form of governance in place?

The purpose of this chapter is to look at the history of corporate governance and to establish that it is not a twentieth-century whim and fancy brought about by questionable financial practices and stock market crashes. Rather, corporate governance is the considered good practice of capable and inspired leaders going back to ancient times. For example, Emperor Tang Taizong created a dynasty of prosperity and productivity that surpassed all others in culture, economy, agriculture and transportation. Taizong ruled from 626 until 649 and his governance was deemed the Confucian ideal – he was a highly intelligent and ethical ruler. He appointed able ministers, kept close relationships with his advisors, took heed to criticisms and led a frugal life. The people who lived under the governance regime of Taizong enjoyed harmony and prosperity whilst the surrounding nations suffered from chaos, division and corruption. He understood the importance of involving his people in governance decisions,

The emperor depends on the state, but the state depends on its people. When one oppresses the people, so that it only serves the ruler, then it is like one is ripping out someone’s flesh in order to fill that person’s stomach. His stomach is satisfied, but his body is injured: The ruler may then be richer, but his state is destroyed. Taizong

(Wu Song 2008)

Too many IT projects thunder ahead without thought for the user who will have to retrain or rethink the way they do their everyday work tasks. Oppression is a strong word to use in this context, but it is certainly possible to upset a stakeholder community through poor IT governance.

His reputation as an erudite political leader stretched well beyond the borders of China. Whilst the surrounding nations suffered from chaos, division and corruption, the people of China enjoyed peace and prosperity.

Just over a hundred years later, we have the example of Darius I of Persia (c.549 bc–486/485 bc, Emperor of Persia 521 bc–486/485 bc). It is particularly interesting to see the progress made by Darius in his reign, and the order in which he accomplished his achievements:

- First, he sorted out outstanding wars, battles, onslaughts.

- Second, he introduced a system of governance.

- Third, he kicked off some large infrastructure projects.

- Fourth, he initiated and developed economic and trading alliances.

- And finally, he extended the empire overseas.

It is useful to take some tips from Darius’s thinking – to make sure there are no outstanding battles across the organisation before you embark on the IT governance work, and to delay the major infrastructure projects until the decision-making framework, policies and processes are established. It is also interesting to ponder on the fact that an organisation with good governance practices in place is in a good position to consider building strong external alliances – and maybe even consider major acquisitions.

Like many CIOs and IT directors, Darius was a surprise appointment – assisted by a team of Persian nobles, he killed the usurper to the throne. The rulers of the eastern provinces saw this as an opportunity to regain some ground, but Darius managed to put down the resulting rebellions. The authority of Darius was thus established. An interesting lesson here is that the rebellious forces within the organisation need to be quelled, and the authority of the CIO/IT director recognised, before effective governance can take place. Darius was a great politician and governor. He revised the Persian administration system and the legal code in an attempt to eliminate bad and corrupt business practices. The lesson here is to tidy up any vendor and internal service level agreements, before embarking on a strategic planning phase. It is unlikely that you will find any corrupt practices, but you might need to address some ambiguities and reset some customer and supplier expectations.

Darius is famous in history, though, not as a law reformer or a great military campaigner, but for his planning and organisational skills. In this he was the true successor to the great Cyrus, and a role model for Herodutus. He limited military campaigns to protecting the national frontiers, and made substantial military reforms to introduce conscription and to ensure his troops were well trained and paid. Internally, he divided the Persian Empire into 20 provinces, each governed by a satrap, who had responsibility for the development of regional laws and administration, and his peers, the financial and military commanders. Together, the three elements made up an executive team that reported directly to the king, who provided ample administrative assistance in the form of scribes – an early civil service. Every region was responsible for paying a gold or silver tribute to the emperor. The system served not only to collect tax to run the empire, but also to lessen the chance of another internal revolt. There are lessons here for the cross-organisational internal IT procurement spending.

Darius took on some ambitious infrastructure programmes during his reign – he built sturdy city walls around his new capital city, Persepolis, he dug a canal from the Nile to the Suez, and he commissioned an extensive and well serviced road network across the nation. The Persian Empire became the envy of it’s neighbours. Darius proved that, with the correct authority and processes in place, an organisation can embark on ambitious projects to provide it with a significant market advantage over its competitors.

Darius was also gifted as a great economist and commercial leader, and his reign resulted in a significant increase in population and the development and growth of many flourishing industries. He understood how to build the respect of his people (for example through his no slave policy) and the role of different ethnicities, and he developed the respect of Babylonian, Egyptian and Greek leaders. In the same way, the successful CIO or IT director must understand and deliver to the needs of different parts of the business, and develop some good allies across the organisation. Did Darius make mistakes and errors of judgment? Yes – and it is to be expected in a reign of 36 years! Like all good leaders, he owned up to his mistakes and handled the fall-out from bad decisions with great diplomacy. As IT leaders we will be certain to make mistakes and errors of judgment – it is how we handle them that counts.

It is another 2,000 years before we read about the role of women in governance. In the provinces of Peru, in the time of the Incas (1438–1533), the women learned ‘skills related to governance’ in addition to Inca lore and the art of womanhood (spinning, weaving and brewing). Inca ‘talent scouts’ would tour the villages and bring promising young men and women to the Acllahuasis, where they would receive training. Alas, only some of the women would get to use their skills in governance – the rest would end up as secondary wives of the Inca king or rewards to men who had pleased the sovereign in some way. It is an interesting idea – to scour your organisation for men and women who show leadership potential and then to provide them with special training in governance. We spend a good deal of money in our organisations training our staff to manage, but we rarely send anyone other than our new directors on governance courses. Thankfully, we no longer use our skilled women as rewards for our high performing men! Well – not in New Zealand, anyway.

![]()

Governance lessons learned from history:

- Establish your authority and develop allies across the organisation.

- Set up clear processes and responsibilities.

- Understand and deliver to the needs of the business.

- Own up to mistakes and handle them effectively.

- Look for leadership potential within your organisation and provide training.

- Tidy up vendor and internal service level agreements; address ambiguities and (re)set expectations.

It is another 300 years before we see legislation around corporate governance and governance structures in the form of the Chartered Companies Act 1837 and the Companies Acts 1862 – 1893 in the United Kingdom. These Acts together cover a range of activities from the governance of seals, stock, associations and registration to the winding up of companies. In 1960, some 70 years later, an agreement was signed that resulted in the set up of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) to,

promote policies designed:

- to achieve the highest sustainable economic growth and employment and a rising standard of living in member countries, while maintaining financial stability, and thus to contribute to the development of the world economy;

- to contribute to sound economic expansion in member as well as non-member countries in the process of economic development; and

- to contribute to the expansion of world trade on a multilateral, non-discriminatory basis in accordance with international obligations.

(OECD 2004)

The original member countries of the OECD were: Austria, Belgium, Canada, Denmark, France, Germany, Greece, Iceland, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey, the United Kingdom and the United States. Since then, Japan, Finland, Australia, New Zealand, Mexico, the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, Korea and the Slovak Republic have joined the original members. The OECD Principles of Corporate Governance were developed in response to a request from an OECD Council Meeting at ministerial level in 1998 to produce a set of corporate governance standards and guidelines. The OECD defines corporate governance as:

Procedures and processes according to which an organisation is directed and controlled. The corporate governance structure specifies the distribution of rights and responsibilities among the different participants in the organisation – such as the board, managers, shareholders and other stakeholders – and lays down the rules and procedures for decision-making.

(OECD 2004)

The first published guidelines were endorsed by OECD ministers in 1999, and they provide guidance for legislative and regulatory initiatives. The principles were revised again in 2004, and the revised list is as follows:

- Ensuring the Basis for an Effective Corporate Governance Framework

• The corporate governance framework should promote transparent and efficient markets, be consistent with the rule of law and clearly articulate the division of responsibilities among different supervisory, regulatory and enforcement authorities.

- The Rights of Shareholders and Key Ownership Functions

• The corporate governance framework should protect and facilitate the exercise of shareholders’ rights.

- The Equitable Treatment of Shareholders

• The corporate governance framework should ensure the equitable treatment of all shareholders, including minority and foreign shareholders. All shareholders should have the opportunity to obtain effective redress for violation of their rights.

- The Role of Stakeholders in Corporate Governance

• The corporate governance framework should recognize the rights of stakeholders established by law or through mutual agreements and encourage active co-operation between corporations and stakeholders in creating wealth, jobs, and the sustainability of financially sound enterprises.

- Disclosure and Transparency

• The corporate governance framework should ensure that timely and accurate disclosure is made on all material matters regarding the corporation, including the financial situation, performance, ownership, and governance of the company.

- The Responsibilities of the Board

• The corporate governance framework should ensure the strategic guidance of the company, the effective monitoring of management by the board and the board’s accountability to the company and the shareholders.

(OECD 2004)

In 2006, the OECD published an assessment methodology for the principles. This document includes a set of sub-principles with measurable outcomes – a format that could usefully be adopted to create an assessment for the ISO 38500 family of governance standards. In 2008, OECD launched a programme of work to develop guidance documents in response to the problems highlighted by the global financial crisis. This work was published in three phases as follows:

- Corporate Governance Lessons from the Financial Crisis;

- Corporate Governance and the Financial Crisis: Key Findings and Main Messages;

- Conclusions and emerging good practices to enhance implementation of the Principles.

Although the three documents deal specifically with the financial aspect of corporate governance, there are some very interesting findings regarding risk management, evaluation and monitoring. Boards had approved strategy but then did not establish suitable metrics to monitor its implementation. Information about exposures in a number of cases did not reach the board, or the senior levels of management in some cases. Boards found that they could not easily access ‘accurate, relevant and timely information’.

CADBURY REPORT

In parallel to the work initiated in the OECD, a succession of company debacles in the UK led to the setting up of a committee in 1991 to investigate the British corporate governance system and to suggest improvements. The aim of the work of the committee was to restore confidence in corporates. This committee was chaired by Sir Adrian Cadbury, and the resulting Cadbury report, entitled The Financial Aspects of Corporate Governance, was published in 1992. This report included a code of practice with the suggestion that this code would be referenced by listed companies reporting from mid-1993 onwards. The report includes a very concise definition of corporate governance, and this definition is referenced in the corporate governance of ICT standard, ISO 38500:

‘Corporate governance is the system by which companies are directed and controlled.’

The report makes it clear where responsibility lies:

‘Boards of directors are responsible for the governance of their companies.’

2000 TO CURRENT DAY

There have been a number of IT related corporate fiascos since the 1990s and a number of legislative responses, such as the Sarbanes–Oxley Act 2002 in the US. The current focus of corporate governance guidelines is around addressing risk – and in particular dealing with fraud and corruption, but interest in corporate social responsibility and company ethics is growing. The publication of the corporate governance of ICT standard in 2008 was designed to address some of the residual issues relating to the handling of IT systems and electronically held information. For more information on corporate governance, explore the information provided by the Institutes of Directors across the world. The UK Institute of Directors, for example, provides a range of material including briefings, training, online business support, networking opportunities and access to meeting spaces. Membership benefits include access to subject matter experts on a one-to-one basis. Similarly, the Canadian Institute of Directors provides a wide range of services and materials and access to a news and knowledge database. The Egyptian Institute of Directors provides a number of conferences and seminars for members, training, research and publications. The New Zealand Institute of Directors provides training, guidance and articles relating to the developing area of corporate governance, including a valuable reference book titled The Four Pillars of Governance Best Practice (2012). The book is a practical guide to the day-to-day issues of being a director. The basic premise of the guide is that a best-practice board is a value-adding board. The four pillars of value underpin the role of director and board member. They include determining purpose, an effective governance culture, holding to account and effective compliance. Besides providing a wealth of information on governance and building effective boards, the guide also includes a chapter specifically on IT and the board. It could be a useful tool to bridge the board–IT gap.

With the premise in mind that every board is unique and often benefits from independent advice, review and facilitation, the various director institutes around the world work with boards on issues as diverse as reviewing governance policies, practices and board operations, strategy formulation and reviewing governance structures.

The challenge is to find material that resonates well with your board and then to apply the models, practices and policies to the corporate governance of your information and IT systems. If you are lucky enough to have an Institute of Directors close by, you could look at building some customised seminars that help build your IT governance framework into your existing governance framework. The useful supporting services will assist you in appointing directors who will be a good fit to your evolving board.

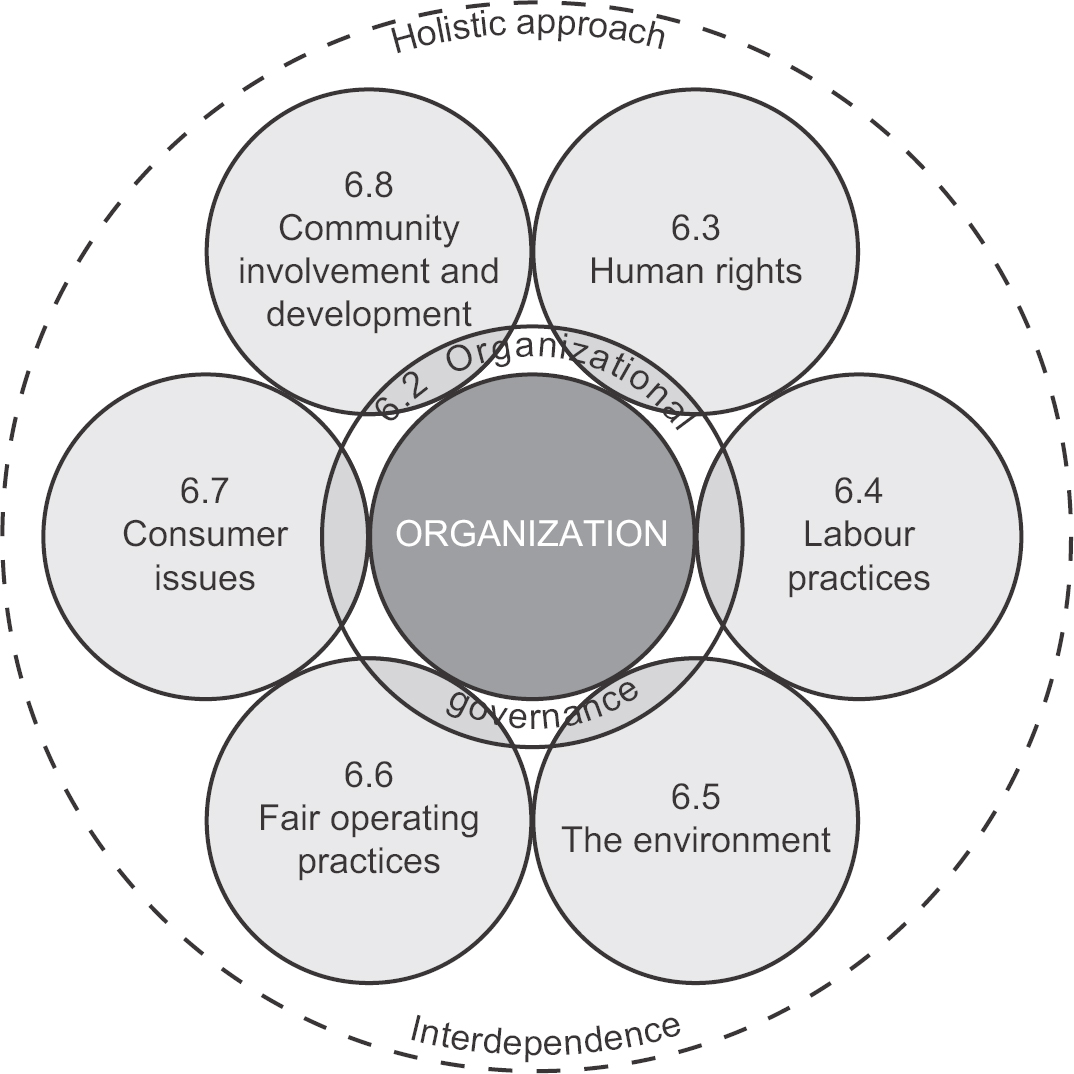

ORGANISATIONAL GOVERNANCE

I was fortunate enough to be involved in the early stages of the development of the first standard to cover the principles of social responsibility when working with the organisational governance group. We used the term ‘organisational governance’ to ensure that the standard covered all types of organisation. The 2010 publication, ISO 26000 – Social Responsibility, which provides guidance to organisations on various aspects of social responsibility – societal, environmental, legal, cultural, political – lists a set of principles to guide organisational policy in this area (see Figure 1.1). The standard defines the term ‘organisational governance’ and promotes good governance activity as the hub from which the work to implement the principles can flow. There is recognition that without good governance in place, an organisation, however dedicated to becoming socially responsible, is unlikely to fully achieve goals in this area with consistent quality deliverables. The same is true for IT. Where there is poor organisational governance practice in place, it will be difficult to implement good IT and information practice that delivers consistent quality deliverables. However, where there is good governance practice in place, introducing the IT governance standard should be a simple case of mapping the principles into the existing governance framework. And though the title of the ISO 38500 standard includes the word ‘corporate’, the principles should apply to any organisation, in the same way that the bulk of the excellent governance material emanating from institutes of directors around the world will bear fruit in any organisation.

Figure 1.1 Organisational governance at the core of ISO 26000