4 THE STANDARD IN DETAIL

So now we know what the standard does in the way of providing advice and how it came about, let us look at how it is structured. First, we make no apologies for the fact that the standard is short in length. The standard is designed to be read by busy people and is divided into three sections for easy reference, as follows:

- Scope, application and objectives – covering who should read the standard and why.

- Framework – covering a set of principles and a model demonstrating IT governance tasks and activities in an organisation.

- Guidance – providing some examples of how the standard could be applied.

SCOPE AND OBJECTIVES

The scope of the standard is to provide guidance for directors of organisations – those who are responsible for directing activity involving IT resources and who have overall responsibility for ensuring that organisational information and systems are accurate and secure. The term ‘IT resource’ covers any asset used to deliver information or communication services to the organisation – and these resources could be owned and managed internally, owned internally and managed externally or owned and managed externally. Also note that not all the IT assets will necessarily be under the direct management of the organisational business unit responsible for IT services.

If you bought the standard hoping that all your IT management questions would be answered, you could be disappointed. The aim of the standard is to arm the directors, trustees or those directing activity with a good set of evaluation questions and guidelines for setting up a good decision-making framework for all IT-related decisions. Good decisions can only be made if the decision makers are in receipt of good quality and accurate supporting information, so another key part of the governance activity is setting up monitoring and reporting.

The key objective of the standard is to provide confidence for all stakeholders of an organisation that, if the principles of the standard are understood and followed, they can trust in the corporate governance of the IT provision. If we are to learn anything from the chaos caused by subprime mortgage lending in 2007–2008, it is that governance is not the common sense we all thought it was.

The standard is written as advice for board members, trustees, directors, partners, senior executives or those carrying out governance activities. However, wise IT managers will want to read the standard as a ‘heads-up’ on the questions that might come to them from above, IT auditors will want to align their services to the conformance aspect of the standard, and IT consultants will want to understand how implementing the standard can benefit an organisation. Internal and external service providers will need to understand the monitoring and reporting aspects of the standard.

The ISO IT governance working group has been working in this area with the aim of issuing guidelines for IT managers working with multiple technology partners. The problem we see is that an IT director, in an organisation running a mix of outsourced and in-house systems, could be dealing with a number of vendor partners and business unit managers, a mixed portfolio of services and products and a resulting jumble of unconnected service level agreements. Everything runs smoothly from the service management side until a problem (or incident of unknown cause) occurs and several systems and vendors are implicated. How are the internal and external providers expected to work together? How do the service level agreements work together? Technology partner governance is just one of several areas that we have been evaluating as a group.

FRAMEWORK

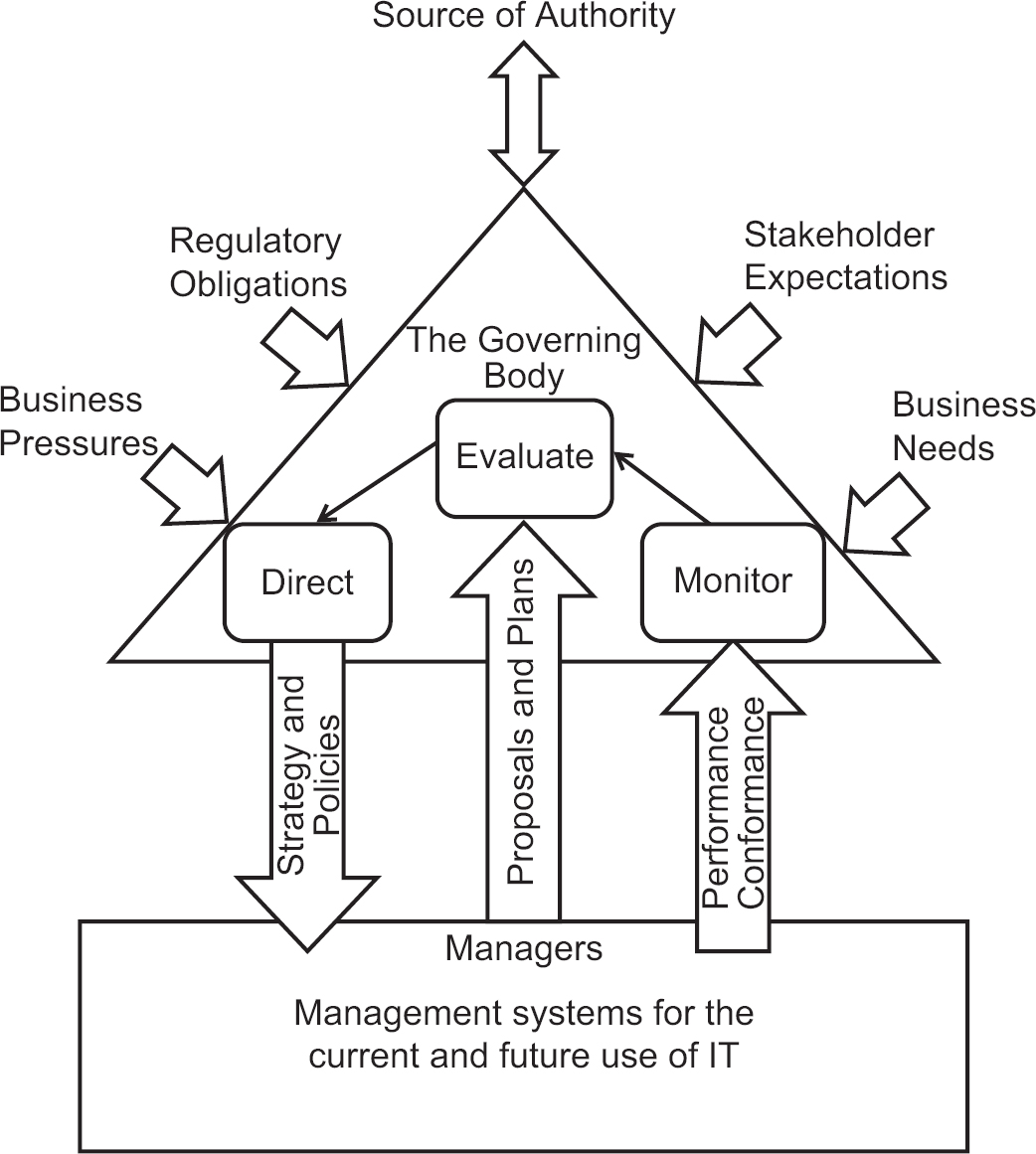

The second section of the standard provides a framework of six principles and a model showing how IT governance and IT management interact, and how all activity needs to span the IT lifecycle from concept through to retirement. This part covers the governance–management glue; the processes that ensure the continual flow of appropriately targeted information between the two domains.

The six principles of IT governance

As a mathematician by training, I would like to know whether all six principles are required to guarantee good IT governance, and I would like to know the weighting that should be applied to each principle. Alas, it is too early to say for certain which of the principles is the most important, and whether all are required. However, we do know from applying the standard that organisations which apply all principles appear to have fewer IT problems than those which do not. From my own implementation of the standard and research, I deduce that the sixth principle appears to be the most valuable. Of all the IT disasters I have had the privilege to investigate, most were caused by human error or by lack of human understanding of the IT system in question.

I have presented on the principles many times in many countries over the last five years. Initially, I used to talk about the positive effects of applying the principles, but I have found that an audience learns more by knowing what could go wrong without the principles in place. So with an emphasis on failure rather than success, we will take a look at each of the principles:

- Principle 1 – Responsibility

Individuals and groups within the organisation understand and accept their responsibilities in respect of both supply of and demand for IT. Those with responsibility for actions also have the authority to perform those actions.

- Principle 2 – Strategy

The organisation’s business strategy takes into account the current and future capabilities of IT; the strategic plans for IT satisfy the current and ongoing needs of the organisation’s business strategy.

- Principle 3 – Acquisition

IT acquisitions are made for valid reasons, on the basis of appropriate and ongoing analysis, with clear and transparent decision making. There is appropriate balance between benefits, opportunities, costs and risks, in both the short term and the long term.

- Principle 4 – Performance

IT is fit for purpose in supporting the organisation, providing the services, levels of service and service quality required to meet current and future business requirements.

- Principle 5 – Conformance

IT complies with all mandatory legislation and regulations. Policies and practices are clearly defined, implemented and enforced.

- Principle 6 – Human Behaviour

IT policies, practices and decisions demonstrate respect for human behaviour, including the current and evolving needs of all the ‘people in the process’.

With an acknowledgement that the principles are not necessarily listed in order of importance, we start with Principle 1 – Responsibility.

Principle 1: Responsibility

![]()

Individuals and groups within the organisation understand and accept their responsibilities in respect of both supply of and demand for IT. Those with responsibility for actions also have the authority to perform those actions.

When we started planning to do some work in the area of IT governance, I was bombarded by suggestions from CIOs from different parts of the world and there was a common theme to their requests, which went something like this:

I’m a CIO of a medium-sized organisation and over the last two years I have introduced service management processes and policies, tidied up the legacy software, rationalized our vendor offerings (etc. etc.) and we now run a very efficient IT department. However, I have no control over the activities of my peers (CFO, HR manager and other non-CEO CXOs) who continue to purchase software (sold to them as business enablers) that does not fit with the IT environment as laid out in the ISSP (Information Systems Strategic Plan) that has been agreed with our board. I now need to hire additional developers/business support/servers to support the new payroll/HR/product management/ecommerce system, and I will be expected to fund this from my budget.

The CIOs were, in general, advocating a standard addressed to boards to assist with better cross-organisational decision making. There is another point here, though. It is all very well giving CIOs responsibility for organisational IT and IT systems, but if they do not have the authority to say no when necessary, then things are not going to turn out well. I have seen the fall-out from such cases as described above, where the CIO ran over budget and was then demoted to reporting through the CFO. If CIOs do not have a chance to discipline their peers, how much less likely are they to be successful saying no to their superiors?

On the other hand, though, I have witnessed a case where the CIO had all authority and no responsibility and that also turned out badly, with parts of the organisation running on systems and constrained by processes that made their jobs far harder than they should have been. There was a constant war between the IT department and the rest of the business and both sides considered each other to be unreasonable.

The moral of the story is to hire the right people (and remember you cannot add on personality with training, but you can add IT and business skills) and empower your people to do the job assigned to them. It is not just the CIO you need to be concerned about, but the entire IT team. If you inherit an existing IT team, you will have to work with what you have – you probably will not have the luxury of starting from scratch. I advise you to go through the CVs of all your staff very carefully and find out what exactly they were hired for. IT people – especially able ones – tend to drift through an organisation like sheep. One minute they are developing code and the next they are fixing the network on a full-time basis, because they were the only person around when the network went down and at least they understood the instructions for getting it back again. Find out what their skills are and try to put them in a position that best uses them.

Once you have hired the ‘right’ IT people, or you have shuffled an existing team, you need to write clear job descriptions for them so that they know exactly what their responsibilities are and who they should be engaging with internally and externally on a day-to-day basis. You need to assign them to good managers who will take care of them and stop them from straying across the organisation. For your frontline staff, you might consider sending them on some sort of service management training – ITIL or ISO/IEC 20000. Again, it is easier to hire bright technical staff and teach them telephone skills than vice versa.

![]()

One of my most able and productive support personnel was a young man who was deaf. He answered all ‘calls’ via messenger applications and he rarely got disturbed when he was rebuilding desktops, so our build quality went up considerably. The local deaf community would send in an interpreter for team and company meetings, and they were kind enough to offer the whole team deaf awareness training.

Once you have your team mobilised ready for action, you need to educate the wider organisation as to what the IT team do and how they do it. You need to set some expectations as to how and when staff might interact with the IT team. I have seen staff hide behind pillars to jump out at passing members of the IT team to ask a question, rather than go through the formal process of logging a support call. I have facilitated a client meeting where we were attempting to find out what was wrong with the client change process. One of the staff complaints was ‘we asked for a server and you gave us a server and we did not need a server’. It is a common complaint – a member of staff makes a request, and the IT team member answers the request without asking any probing questions to see if the request is reasonable. Or the staff member makes a request and the request is instantly refused because the request does not fit with the budget/strategic plan/current infrastructure. Neither situation is good. I suggest to my clients that they develop a charter between IT and the main business units to agree on which services will be delivered and how they will be delivered and, most importantly, how new services will be developed and rolled out (see Appendix B). In IT service management language, the charter provides a relationship document that includes an IT service catalogue, an issue management process and a change request procedure. I also coach IT staff to help them ask better questions, or at least to have a discussion around requirements, and to never say no to paying customers.

![]()

Years ago I was an IT manager in an organisation where the HR department decided that their services should be available 24x7x365/6. My team put together a quote for load balanced high availability systems, and it turned out that the HR manager did not have the budget or desire to pay for high availability IT systems. There followed a discussion around business requirements. The HR team were mainly concerned that, if the IT systems were unavailable such that they could not process the payroll, then they would not be compliant to New Zealand employment legislation, and non-compliance came with hefty penalties. To cut a long story short, we came up with a CD based solution that cost less than $100 NZD per year, and satisfied all parties.

Eventually you will find that your IT team will get used to asking better questions and your staff will get used to providing clearer answers. Never saying no to requests involves the requirement to come up with imaginative solutions, and often the most imaginative solutions are also the most cost efficient.

To summarise the first principle, you need to establish clearly understood responsibilities for IT such that all individuals and groups within the organisation, however IT-savvy they are, understand and accept their responsibilities for IT.

Principle 2: Strategy

![]()

The organisation’s business strategy takes into account the current and future capabilities of IT; the strategic plans for IT satisfy the current and ongoing needs of the organisation’s business strategy.

When we first started researching companies that were good at IT governance, we discovered that they appeared to be more successful than similar companies not applying good principles of IT governance. However, then we noted that the companies that were good at IT governance were good at governance in general. In the same way, I have noted that companies who are not strategic about their use of IT often do not have a clear organisational business strategy. In such cases, there are normally some meaty statements in the organisation’s annual report or statement of intent, upon which you can latch a sound IT strategy. And holding interviews with senior managers and board members around the current and ongoing organisational needs can be very revealing. Every viable, healthy organisation has some form of a plan, even if it is short term or existing only in the CEO’s head. And most business plans include an IT element, even if it is invisible to the plan’s author.

![]()

I have had a situation where I have developed an IT strategic plan to align with the vision and mission of an organisation, only to have the organisation decide to revisit the vision and mission as the IT plan was presented. In the light of my experience, I would suggest that it is worthwhile finding out how widely adopted the vision and mission are before aligning the IT plan. Not everybody will be able to quote the vision, however succinct it is, but everybody should understand the spirit and intent of the organisation.

If you are going to be spending any money, it is probably safe to assume that the organisation is going to be gearing for growth and it is also likely that the organisation will be expecting some form of financial return on investment. Few companies will have the appetite for new IT systems and services whilst they are treading water or are preparing for shut-down mode. You will not always be able to guarantee a dollar return on the initial investment – you might be upgrading systems to meet a conformance or compliance need, or you might be replacing legacy or ‘twilighted’ software. However, subsequent investment to build systems on your now supported, maintained and compliant platform should be able to deliver services that translate to dollar savings or dollar return.

IT strategic plans can be confusing, so it is not worthwhile attempting to write one plan to meet the needs of all audiences. The board need a high-level plan that gives a rough idea of the required investment and the returns that will be delivered. I suggest that you write the board plan in such a way that the line items, when presented electronically, can be used as hyperlinks to drill down to the detail required for the management team layer, and that the management tasks can be drilled down to provide detail for the operational team.

In Table 4.1 I split the high-level plan into six sections – three vertical sections representing this year, next year and the year after, and two sections horizontally –the things we intend to do (implement) this year and the things we intend to do (prepare) this year, ready to roll out next year. Often when we make an IT strategic plan, we ignore the fact that there are things we need to put in place before we can get started on implementation, and we find ourselves running six months behind before we have even started. The last bottom right-hand segment of the plan should include the planning process for the next three-year plan.

You might be asking whether a three-year plan is too short, but three years is a long time in IT, and the cost effectiveness of different service types is linked to a number of national and global economic factors. Even if your organisation has a very clear long-term plan, it might not be true that the most effective and efficient way to deliver services to, for and from the organisation remains constant across the time period.

Table 4.1 Work programme planning

In summary, the organisational business strategic plan and the IT strategic plan need to be kept aligned to ensure that the IT provision is always ready to meet developing and evolving business requirements. In keeping the plan concise and succinct, it is easy to modify it to adjust to any change in direction. The process of maintaining alignment is best managed through formal workshop sessions with key business and board representatives. These sessions should be scheduled to run regularly with an understanding that any significant change in the business should prompt an extra meeting. I have found that mature, successful organisations take these sessions very seriously – their key representatives are invited by name and are expected to attend and not to delegate responsibility. Ironically, the organisations that most need to change the delivery of their IT systems to meet their strategic goals are the organisations least likely to see the value in holding a strategic planning session with their IT advisors.

Principle 3: Acquisition

![]()

IT acquisitions are made for valid reasons, on the basis of appropriate and ongoing analysis, with clear and transparent decision making. There is appropriate balance between benefits, opportunities, costs and risks, in both the short term and the long term.

We are very fortunate in New Zealand to have a set of sensible guidelines for procurement freely available from the office of our auditor general. The guidelines are written for public entities, but they cover the full range of procurement stages and predicaments and, if followed closely, appear to lead to good and transparent procurement decisions.

A few years ago we did some international research into the success of IT projects, and we discovered that the failure rate was very high. I am sure that in itself will not be a surprise to you, but there were some surprising facts that emerged.

There were a number of IT projects that failed to meet business benefits, but there were an astoundingly greater number of IT projects that were kicked off without any thought to business benefits at all. I might just possibly buy the odd pair of shoes without giving consideration to the return on investment or the benefits that I would expect to extract from them, but I would not expect to embark on a multi-million dollar IT implementation without casting my mind to the potential benefits.

Poor IT acquisitions are based on poor decisions, possibly an outdated view of how IT systems work and can add value, or a lack of ability to think with a services rather than parts mindset. Poor IT acquisitions are often made in a hurry – and often by the organisation that did not think it was worthwhile setting aside time to plan IT strategically. Poor IT acquisitions do not take into account alternative options and they are often based on choosing the cheapest solution, even if spending a few dollars more would extend the life of the solution significantly.

![]()

Here are a few tips for making good procurement decisions:

- Gain a thorough understanding of required benefits before you start.

- Have a series of informal chats with prospective vendors to help develop your understanding of what you are about to purchase.

- Look for and use good procurement guidelines to ensure a fair, open and successful experience.

- Devise a marking scheme that deters anyone trying to rig the results.

- Visit/find out about organisations that are now doing what you want to do, and see what systems they are using.

- Gain a thorough understanding of the implications of the ‘do nothing’ option.

- Check out references as early as possible in the process.

- Test your shortlisted systems with your own data and processes through a well written case study before making a decision.

- Do not exasperate your vendors by burning hour upon hour of their pre-sales time with ill-conceived questions.

- Look for systems that can be configured rather than customised to cut down on implementation and ongoing maintenance costs.

- Assess potential vendors to see how well they would work with your staff.

- Review training and roll-out options and make an organisational change management plan as early as possible.

- Make sure you meet the likely project team members before you sign a contract.

- Communicate with the wider organisation through the different procurement stages to ensure that staff know why you are making a purchase and what is expected from it.

- Go and visit vendor reference sites early on.

Time and budget are important, of course, but they are secondary factors in comparison to fit and to requirements, and having the whole organisation understand why the procurement is being made. You are unlikely to be able to modify the time element significantly and, if you do, it will result in a leap in cost and might impact the organisational culture in a negative way. As for the cost, even if the proposed solution is beyond the initial budget, you might be able to justify it through return on investment figures, or you might want to approach the implementation in stages.

Remember that purchasing cloud-based solutions necessitates a modified procurement process. It is possible that by the time the vendor has completed a proof of concept, they have just about delivered your final solution. To manage the risk of purchasing the wrong solution, and to be fair to your vendors, you might consider paying for the proof of concept phase – especially if the work done can be recycled into the final delivered solution if you decide to proceed.

And finally, ensure that IT-related acquisitions are managed well across your organisation. It is unreasonable to expect your CIO to take on support for business systems where they have had no influence on the procurement process. The ad hoc procurement of a business system or package, without reference to the IT team, can result in a security or maintenance nightmare that must be funded from the IT budget. It is also unreasonable for the CIO or architecture team to have the final word on all IT-related procurement decisions, as this can be limiting for the vendor management team who are trying to balance business needs and financial constraints. The answer is to ensure that whoever in your organisation has responsibility for vendor management is mandated to take into account the considered view of the CIO or architecture team when processing an acquisition request, irrespective of the value of the dollar spend. The roll-out of an almost free piece of software can be as disruptive as the roll-out of a replacement fully fledged payroll system if the roll-out results in the need for new support skills or raises new security risks.

In summary, make sure your acquisitions are made for valid reasons, and find out if you can recycle the systems or services they are replacing.

Principle 4: Performance

![]()

IT is fit for purpose in supporting the organisation, providing the services, levels of service and service quality required to meet current and future business requirements.

We can generally recognise when IT systems are underperforming, though it is not always obvious unless your organisation is heavily dependent on IT. We rarely recognise when our IT systems over-perform. It can be very expensive and yet it can come about very easily. We get carried away with a desire for unnecessary high availability, and purchase redundant systems or we replace desktops or laptops with high-end machines that are way beyond the user requirements. A faster processor is a great thing to have for the users doing a lot of processing or heavy number crunching, but the average office user writing emails and producing documents might not notice a great deal of difference. Often we over-procure for reasons of convenience as having everyone on the same desktop platform makes support and maintenance more straightforward. Sometimes we over-procure as a knee jerk reaction to a disaster – we run out of space on a server and as a reaction we run out and buy more space before we have even considered the root cause of our capacity issues.

From an organisational view, the best response for dealing with such problems is to find the root cause for the capacity/performance issue. You might be witnessing a dramatic increase in sales – in which case you would want to procure smartly to increase capacity and performance, and you certainly would not want to disable the service that is bringing in so much extra revenue. Alternatively, you could be under some sort of denial of service attack, whereby increasing capacity and performance will only exaggerate the problem. Even then you probably would not want to shut down the service if that meant losing all sales. You would want to smartly procure a remedy in the form of software or hardware or reconfiguration services to deal directly with the cause of the problem.

As I write this, it is day four of my monthly Internet plan and I have received an email to say that I have burnt through 80 per cent of my monthly allowance of 10 GB. Eek! I am just 2 GB away from dial up speed Internet. A not-unusual IT reaction would be to go out and buy more broadband capacity, but only a few seconds of consideration tells us that this is an expensive problem and that there is probably something fundamentally wrong. First, let us consider the last six months – average use per month is 6 GB and the highest monthly figure is less than 7 GB. My provider suggests that I have evil neighbours hacking into my system. (The call centre representative did not actually use the word ‘evil’ but the tone of the comment was that used to describe rapists and murderers.) I am concerned that my provider has opted to start charging for Tivo downloads, but I am assured that this is not the case. It is just as well. (For those of you who do not know Tivo, the box monitors the kind of TV programmes that you watch and download, and thoughtfully records ‘suggestions’ that fit your viewing profile. Our Tivo box is convinced that we are Chinese, and it would gall me to think that I might be paying for a raft of downloads that I cannot even understand.) Obviously, the problem can be ‘solved’ by turning my wireless router off permanently – and I have seen this sort of drastic approach to solving IT-related problems.

So the moral of the story is that procurement should be made with business requirements in place and an understanding of normal usage, minimum usage and peak usage. For normal operations and depending on the nature of your business, you will want to deliver to the high end or the low end of your normal use. The easiest way to determine how vital high performance is to your organisation is to run a proof of concept on a low performance system.

![]()

I was told the story of a systems manager who was continually purchasing additional disk capacity to meet the needs of the ever-expanding email system. After a while, it became evident that if she continued on this course of action, the system back-ups would not be able to complete in the time allocated. Of course, the answer to this problem was to introduce policy around individual email usage and to introduce users to the process of archiving old email, but nobody wanted to inflict policy on the users. Eventually the problem came to a head. The service desk team, gravely concerned that the email system was yet again running out of space, decided to send a request to all the users, asking them to archive their email as a matter of urgency. Surprisingly, it was not the big group email that the service desk team unwittingly used to notify the users that took out the email system, and in fact it was not the email system itself that collapsed. Rather, it was when hundreds of users all attempted to archive their email that lunch time that the file system fell over and apparently took several days and a number of bright systems engineers to return it to working order.

In the case of an emergency where your performance and capacity needs change suddenly and dramatically, you will want to procure a remedy as quickly as possible, but not before ascertaining the root cause of the emergency situation. Even then, you will want to be sure that the ‘cure’ is not worse than the problem itself.

Principle 5: Conformance

![]()

IT complies with all mandatory legislation and regulations. Policies and practices are clearly defined, implemented and enforced.

Of all the principles, I feel that this should be the most straightforward to work to, but it really is not. Clear requirements laid down in legislation do not always translate into clear direction for IT, and legislation that is hard to get your head around to start with is even more difficult to get your IT systems around. Consulting a lawyer might not be as helpful as it sounds, unless you are really struggling with the interpretation of the law or your method of implementing your interpretation of your requirements involves issuing a warning rather than developing an IT system. One of my clients had a two-stage implementation of policies and practices to meet the requirements of the new copyright infringement laws in New Zealand. Stage 1 did involve a lawyer and a piece of paper, and was relatively straightforward. Stage 2 involved a radical overhaul of the systems providing wireless access to visitors, starting with the purchase, configuration and deployment of a new firewall – no small task.

Another client is getting to grips with the requirements of the New Zealand Public Records Act. The Public Records Act 2005 ‘sets a framework for recordkeeping in public offices and local authorities’. A key purpose of the act is to ‘enable the government to be held accountable by ensuring that full and accurate records of the affairs of central and local government are created and maintained; and providing for the preservation of, and public access to, records of long-term value’. Organisations required to be compliant to the act were given five years to put systems in place. Audits have started and will be carried out every five years. Each audit starts with a self-assessment. The spirit and intent of the act is excellent. With more government data released each year enabling our citizens to self-manage their lives wherever possible, it is essential that the correct versions of the correct documents are made available to the public. Putting in place good record management systems where there has not been anything previously is a lengthy and costly process, but should add to greater work efficiencies over time. From an IT point of view, setting up a record management system is reasonably straightforward. Setting up a compliant records management environment is more complex, but still reasonably straightforward. From a business point of view, though, there are a number of key decisions to be made around what is kept and where, and policy needs to be written to support the desired practice, and to ensure that the practice and policy are maintained. To me, the most difficult element is working out the best option for ‘long-term storage’. Neither CDs nor tapes last forever and disk formats evolve and change.

Achieving compliance in IT systems almost invariably involves radical changes to the accompanying business processes. It is essential that business requirements are fully understood, and that somebody in the organisation runs a sanity check against the relevant legislation to ensure that the delivered system will guarantee compliance before delivery commences.

Sometimes becoming compliant is relatively easy and the problem comes in trying to maintain compliance. Imagine that being compliant to legislation means that you need to keep a copy of every business-related email written in your organisation. That is easy enough to do as a one-off activity with everyone in the organisation involved, but the ongoing maintenance to be prepared for an unannounced audit is a headache. As an IT person, your thoughts might immediately go to the ever-increasing requirement for storage and how you can minimise the storage required. As a business person, your thoughts might go to how on earth you will separate business email from personal email.

So the summary here is that compliance can be a headache – for business and IT – but there are three things to remember. First, there will generally be help available from the group who ‘own’ the legislation, and from fellow organisations who have the same requirement to comply. Second, most compliance activities are viewed as a journey. It is essential to be closer to full compliance this year than you were last year, but it might not be essential to be fully compliant the day the relevant act is passed. And finally, look for a reliable source of information for legislation in development and keep in touch with the progress of legislation that could affect the way you deliver IT services or manage your information. Look for official advice, and help and take it.

Principle 6: Human behaviour

![]()

IT policies, practices and decisions demonstrate respect for human behaviour, including the current and evolving needs of all the ‘people in the process’.

Before we jump into the implications of this principle, let us first consider who the people in the process could be, because, as IT has become more utilised across and more engrained in the business, the number of people involved in the process has greatly expanded. In fact, I would be surprised if there was anybody in your organisation who did not have some form of contact with IT. And then there are all the people who read your website, use your web services – competitors, customers, friends, family, colleagues – people from all over the world who connect with you in some way through your IT systems.

Second, let us look at the word respect. This principle is not just about technology – keeping systems running, providing services – it is also about the way you treat your users and ensuring that IT policies and practices support your aim to treat the consumers of your IT systems with the highest esteem.

Imagine that you are a new member of staff in your organisation and that you have only ever really used computers for checking email and browsing the Internet. How good is the induction for using your IT systems? Is it obvious what can be used, and why and when? How good are you at matching systems and people? Does your induction course cover physical set up (desk height, chair, requirement for special keyboards and so on) to prevent operational overuse problems? Do you have ongoing provision for regular eye tests for staff who continually sit in front of screens? What are your policies for using company computers for personal tasks? How good is the training for your corporate systems that are used by everybody – time sheeting, leave application and so on? How well do your internal systems support disabled people? How do you protect the personal details of your staff from access by other members of staff? How do you prevent your IT systems from being used for stalking or bullying?

And what do you count as acceptable use of your IT systems? Are you content for your staff members to check their bank accounts whilst at work? Read the newspapers online? Sit and watch online auctions? Place a bet on a horse? Download music or movies? Read friend updates on Facebook? Tweet the progress of the latest project? Do you allow your staff to connect to your network at work or at home using non-company devices? Microsoft® Windows 8® has a ‘Kid’s mode’, possibly setting an expectation that the children of your employees will want to play with their parents work devices. Are your staff allowed to connect their personal devices to the company network and, if so, how are you controlling the security of your organisational data on their devices?

How your IT policy sets out rules for using your IT systems will depend very much on what business you are in. If reading the local newspaper every day is part of the job, then you will not be blacklisting the local newspaper site. If you are a long way from the nearest bank, allowing your staff to make transactions from their desk will be a bonus for them and might save them from disappearing for long lunch breaks. Do you have a clear user policy for your IT systems? Is there a clear and common understanding of what could happen if somebody was found breaking the policy? Do you have systems in place for collecting evidence for serious policy breaches? If one of your staff members was collecting unsavoury images or illegal copies of DVDs on their hard drive, would you have the forensic skills in-house to deal effectively with the issue?

It is my experience that most organisations only start to consider these types of policy and practice when a serious problem occurs. I have seen examples where the tools used for policing were totally inappropriate and where the organisation’s ‘police’ themselves were the main culprit. Approximately 80 per cent of organisational fraud is committed by staff members within the organisation. If you are going to protect your organisation and the staff who work within it, you are going to have to consider some preventive measures. As mentioned previously, there is ISO work underway in this area to create guidance under the title of digital forensics governance.

Now imagine you are a customer of your organisation wanting to purchase services through your B2B or B2C sites. Are the sites intuitive? Are they easy to navigate? Can they easily be used by disabled people? Is the site colour-blind friendly? Do you make unreasonable demands on your customers? If your customers are forced to register before they can use your services, have you reviewed the quality of the data that you are collecting? Do you measure the number of returning customers versus one-off customers?

And how about the end customers who use your products that have an IT component? What policies and practices do you have in place to protect them and to ensure a quality interaction? Can you guarantee that your deployed software is fit for purpose?

In summary, this principle requires a lot of work across your entire business, involving anybody and everybody who has or will have an interaction with your IT services and systems. It looks like a gigantic piece of work and it is, but look at the huge benefits of having engaged staff using tools that are neither frustrating nor confounding, returning enthusiastic customers and a bank of data that you can rely on to make business decisions and predictions.

GUIDANCE

The third and final section of the standard provides an example for each of the six principles of how the principle could be implemented. This section breaks implementation activity into three categories – evaluate, direct and monitor – which are the three principal activities of the board. This section is not an implementation guide, but it does provide a taster as to how the standard could be implemented.

When we first started work on developing an international version of the Australian national IT governance standard (AS 8015), we were under pressure to replace the evaluate direct monitor (EDM) tasks with the more familiar and widely adopted PDCA (plan, do, check, act) cycle. After much debate, we concluded that it was not only appropriate but also very useful to have a different cycle and to use different terminology for the activities of the board or governing body of an organisation that would set it apart from the PDCA management cycle and the activities of the management team. Mapping the EDM activities to the PDCA cycle, it becomes very obvious how and where board activities interact with management activities, and it highlights the grey areas of confusion where, in practice, individual board and management team members can get very protective and defensive over what they see as ‘their turf’.

Figure 4.1 Governance framework diagram from ISO/IEC 38502

Evaluate

The standard encourages directors to evaluate continually the current and future use of IT, whilst taking account of the current and future needs of the business. It all sounds very easy in theory, but many boards have been burnt trying to evaluate IT. It can go wrong in two ways – either the information is very difficult to extract or the board are overwhelmed with unnecessary detail and it is a huge mission to work through pages of meaningless reports to work out what is going on. Communication is a two-way street, and for directors to be able to successfully evaluate IT, managers need to be able to successfully provide the relevant and required information (see Appendix A).

The first stage then of ‘evaluation’ is to work out the desired outcome from a board perspective. The board needs sufficient information to answer the following questions:

- Does the current IT strategic plan align with the mission and vision of the organisation?

- Do the IT supply arrangements meet the requirements of the organisation?

- Are we confident that our procurement strategy and ongoing activities meet our requirements to balance benefits, opportunities, costs and risks for the short term through to the long term?

- Are we confident that we have the right people in the right roles managing our IT and information assets?

- Are our IT systems and services compliant and enabling our staff to be compliant with legislation, regulation and our internal policies?

- Do our IT policies, practices and decisions continue to demonstrate respect for all the people who have interaction with our IT systems and services – internally and externally?

And finally the catch-all question:

- What are the key IT-related organisational risks that we should be concerned with?

If you are a board member reading this, you might be asking why you cannot delegate responsibility for answering these questions to your CIO. As a board member writing this, I can assure you that you will be privy to information that the CIO will not have visibility of. For example, you have a clear idea of the key economic, political and social trends and influences that are affecting and will affect the business in the next few years. You will also have a clear idea of where the business is heading in the next one, three and five-year time periods. You need to know that you can maintain competitive advantage, protect developing and developed IP and sustain your market differentiators, and all of these have IT components or associated IT activities. Your organisation might be planning partnerships, mergers or acquisitions, or just planning to share back office services with another organisation – and any of these would have implications for IT delivery and IT service provision. And, finally, you will be privy to financial information – actual and forecast figures – that will influence your view on procurement and supply.

If you are a manager or CIO reading this, you might be perplexed as to what you should be providing to your board in the way of information and reports to enable them to make accurate evaluations. You do not want to provide too little or too much information and you want to provide it in an easily readable format without dumbing it down. Also, you probably see what happens today and what could happen tomorrow as two very different scenarios, so you will want to present the current situation with a ‘heads-up’ on the future. From the paragraph above, you can see that you might not have a clear and accurate view of the long-term future of the organisation, so you can only report against the published plans, but that will be sufficient for the board.

Before any reports change hands, develop a template that covers all the bases for the information required and sets an expectation for the level of detail required. Test out different formats and presentation methods. The board of one of my clients does absolutely everything in Microsoft PowerPoint® and it works very well for them. Dashboards with the ability to drill down into increasingly more detailed information have been very popular.

Speaking as a board member, I am a big fan of the cascading balanced score-card approach (see Appendix A), where different score cards are set up for each level of the organisation, but each lower layer feeds into the level above and the score cards can be read from the bottom up or from the top down. This approach is great for diagnosis when things do not go to forecast. The board wants to know that everything is fine and dandy, without having to wade through pages of reports. However, if there is something that gives cause for concern, they are going to want to dig deeper to see what is happening. The beauty of the cascading score-card approach is that information collected from the operational team can be summarised as part of the management reporting information, and this can then be summarised for the board. Now, if a member of the board wants to reverse the process, they can dig down to the raw data that informed the high-level report that they are looking at.

One of the faults with current governance and management practice is that it is fuelled by the notion that the higher up you are in an organisation, the less you need to know about operational detail. And yet, when we look at some of the recent security failures of European organisations, the source of the errors has been at the coal-face in the operational detail.

One of my colleagues likens the art of governance to steering a ship. I do not need to know absolutely everything about the ship to steer it, but there are some useful indicators that will help me make my decision as to where to steer it. As a board member, I am looking for patterns and anomalies. In the case of the ship, I check that I have enough fuel to reach my destination. If on day two of my voyage, I have used considerably more fuel than I would have expected, I am going to want to know more information than the dashboard view of the fuel gauge can provide. I am going to want to know whether I have a leaky fuel tank or a faulty gauge, and I am going to want to know the information pretty quickly.

Cascading balanced score cards give the board the tools to dig into information as and when they want, without waiting for the next board meeting.

Let us suppose that the cost of producing one of the products has gone up this month and there has been some arm-waving about increasing fuel prices. If the board member is only two clicks away from operational costs on an online report, he/she can find out instantly what is actually going on, without calling a meeting or waiting for management to hold an enquiry.

If you constantly tune your cascading score cards, you will refine the information collection and restrict the indicators to ones that provide reliable and useful knowledge.

My ‘perfect board report’ is less than one page long, and shows a high-level summary position of everything I am interested in (see Appendix A). It provides a status report addressing all six of the governance principles, shows an ISO 31000 compliant pie chart distribution of risk before and after planned mitigation with one sentence on each of the highest risks, a budget summary and, lastly, presents recommendations for board sign-off.

Providing reports to enable the board to evaluate how the organisation is faring against the six principles will depend largely on the size and nature of the organisation. There is an interesting jurisdictional aspect to consider when addressing the evaluation of your conformance requirements and the human behaviour elements. Conformance should be straightforward and easily trackable, but the human behaviour elements need considerable thought if your services are available globally. What might be considered respectable for users in your country might be an insult to users in other parts of the world.

With all new reporting schemas, the best approach is always to start large and modify or cut away the bits that prove not to be useful or informative. By all means operate a regular reporting schedule, but set an expectation that you will want to receive additional reports when particular circumstances arise or specific events trigger an urgent need for information. If you can give your IT team the ‘heads-up’ on the sorts of reports you might want to see as a result of particular events, they can set up triggers in advance. As a board it is worth listing the types of events (including unexpected successes as well as disasters) that would trigger the need for urgent reports, and passing on the list to the IT management team before such an event occurs. The purpose of evaluating your IT systems and services is to ensure that the organisation is fit to handle all and any challenges, good and bad, that come its way.

Direct

The standard describes boards directing the preparation and implementation of plans and policies.

Directors should assign responsibility for, and direct preparation and implementation of plans and policies. Plans should set the direction for investments in IT projects and IT operations. Policies should establish sound behaviour in the use of IT.

(ISO/IEC 38500 2008)

This is directing in the spirit of Star Trek – ‘make it so’. It is not about getting involved in the writing of plans and policies, but neither is it about delegating authority for determining appropriate plans and policies to your IT management team. If you are unable to determine what a suitable set of plans and policies might look like for your organisation, get assistance in the form of a facilitated session for your board from a respected IT/business guru. By the time you realise that your plans and policies are lacking in some way, it might be too late for you or your organisation. Also, do not just try and copy over the plans and policies from another organisation. Even if they run a similar business, they are unlikely to have a similar organisational culture. And if perchance they do tick both of those boxes and you copy their plans and policies, where is your competitive advantage?

First, before you can consider directing activities here, you need to know what the outcome should be. You would be ill-advised to order your management team to ‘make it so’ if you do not know what having ‘it so’ looks like. You do not arrive at a train station and idly jump on the first train that comes along because you need to catch a train. And so it is with plans and policies – you will get on better if you understand the destination and have an idea of how quickly you want to arrive there before you can embark on the journey.

Second, boards are encouraged in the standard to direct and oversee the transition of projects from development into production.

Directors should ensure that the transition of projects to operational status is properly planned and managed, taking into account impacts on business and operational practices as well as existing IT systems and infrastructure.

(ISO/IEC 38500 2008)

This might on the face of it sound like an operational task for a board to perform. However, I know many organisations that have lost money through poor transition of IT systems or the introduction of new IT-enabled systems and services. It is perfectly reasonable to delegate the physical switchover of systems or services to an accomplished IT team, but the IT team cannot be expected to be aware of, or responsible for, the full organisational impact of the change. It is far, far easier to direct and own this activity from the outset and before the change than to clear up any fall-out after the transition has completed. If the operational risk of having systems and services unavailable is not sufficient motivation, there’s the financial risk of losing money from services that cannot be delivered fully or invoiced, and the reputational risk of being seen to run unreliable or faulty systems and services.

Third, boards are advised to direct or encourage the development of a good governance culture within their organisation.

Directors should encourage a culture of good governance of IT in their organisation by requiring managers to provide timely information, to comply with direction and to conform with the six principles of good governance.

(ISO/IEC 38500 2008)

I have observed organisations where the board members are consistently late to meetings and, when they arrive, they check their phones and start responding to emails. They are continually running behind, and they are never fully present anywhere, because they are trying to catch up on the outcomes of the last meeting they attended. The senior managers in the organisation exhibit the same behaviour and so it flows on down the organisation. I use this as an example, not of bad behaviour, but of how the behaviour of the leaders of an organisation will be modelled by the next level down and so on, until the behaviour is adopted throughout the organisation and becomes part of the organisational culture. If, as board members, you are going to develop and direct a culture of good governance, you must first model it. The old adage, ‘don’t do as I do, do as I say’ just does not work when it comes to developing good basic organisational behavioural patterns.

Yet, just modelling good governance alone will not guarantee adoption. You will need to set some very clear expectations for your managers around reporting, completing what they have been tasked to do in the way that they have been tasked to do it, and in adhering to the six principles of the standard. Depending on your organisational culture, you might want to utilise some visual aids or ‘aides memoire’ in the form of calendar reminders, posters and so on, or you might want to assign and reward the organisational champions who embrace good governance principles.

And, finally, the standard exalts boards to intervene, if necessary, where situations require an escalated response.

If necessary, directors should direct the submission of proposals for approval to address identified needs.

(ISO/IEC 38500 2008)

As a board member you might observe a cross-organisational issue or an urgent issue that might not fit within the responsibility of any one particular senior manager. Do not confuse ‘directing the submission of proposals’ with ‘submitting proposals’; and take special care not to confuse ‘if necessary’ with ‘as a general rule’, and all will be well.

Monitor

The third board member activity promoted by the standard is ‘monitoring’. Interestingly, I have met many boards who carry out two of the three activities, but not many who carry out all three. The activity that gets dropped tends to be either evaluating or monitoring. Boards that evaluate and direct but do not monitor set an expectation that performance does not matter and outcomes are not important. Boards that direct and monitor but do not evaluate can set staff on edge or put them in a permanent state of confusion – they are possibly being marked on something where they have no idea what they are expected to do.

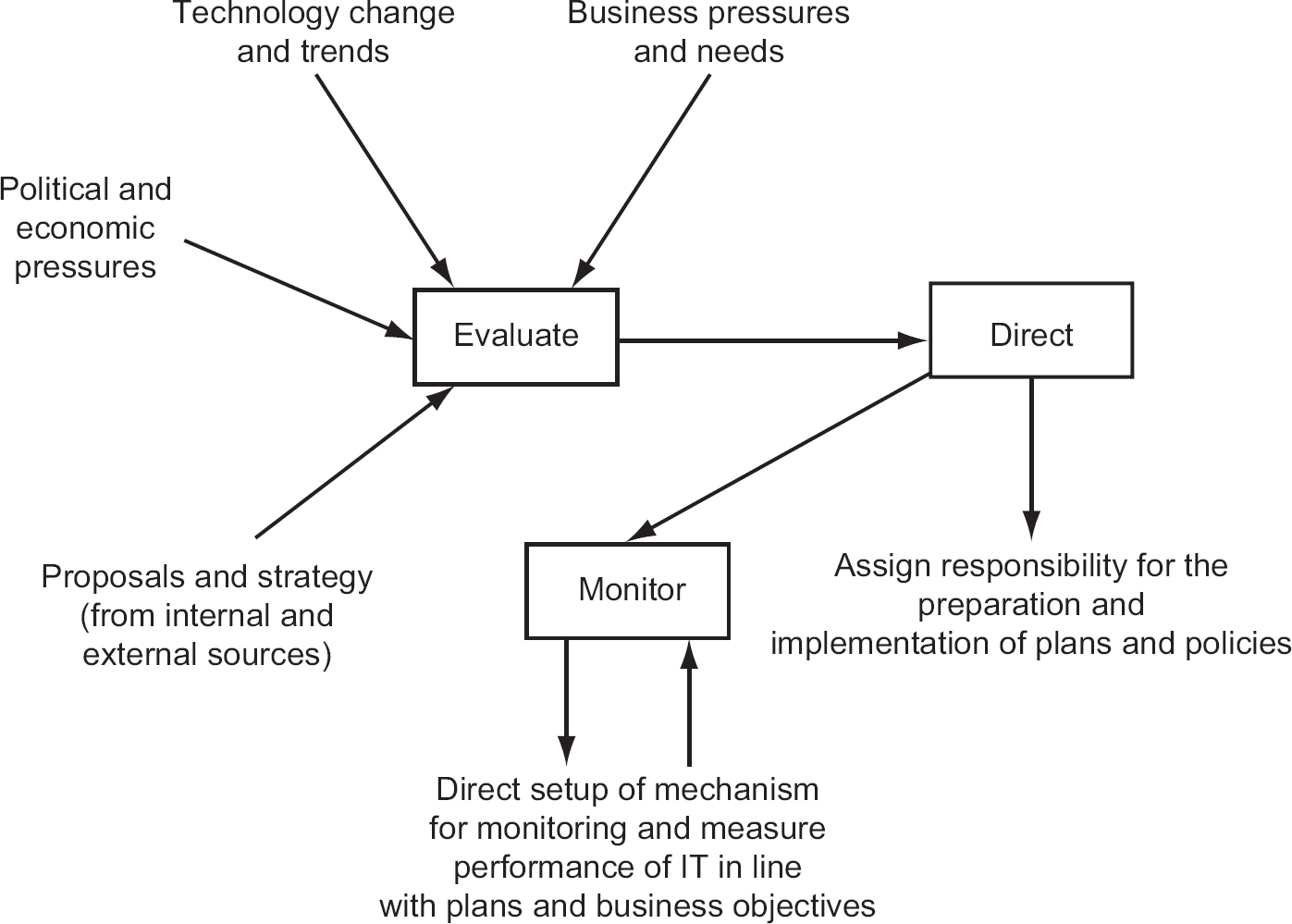

The diagram on Figure 4.2 shows how the governance activities of evaluate, direct and monitor work together.

If you think of the evaluate-direct-monitor model as three parts of a cycle rather than as three independent activities, it becomes clear that, having evaluated what needs to be done, the board can direct activities to meet requirements and to deliver in the short and long term. Then, having set everything in place, the board can monitor outputs and outcomes to check that the organisation meets internal and external obligations for performance and compliance, that all associated and related activities are in line with the stated strategy and that they demonstrate respect for all the people involved along the way.

Directors should monitor, through appropriate measurement systems, the performance of IT. They should reassure themselves that performance is in accordance with plans, particularly with regard to business objectives. Directors should also make sure that IT conforms with external obligations (regulatory, legislation, common law, contractual) and internal work practices.

Note: Responsibility for specific aspects of IT may be delegated to managers within the organisation. However, accountability for the effective, efficient and acceptable use and delivery of IT by an organisation remains with the directors and cannot be delegated.

(ISO/IEC 38500 2008)

Figure 4.2 Evaluate-direct-monitor activities

It is obvious that the board must be responsible for the legal compliance aspects of IT provision and delivery, and board members should be aware that non-compliance could result in a jail sentence. The standard also makes it very clear that monitoring the effective, efficient and acceptable use and delivery of IT by an organisation cannot be delegated. Ineffective, inefficient IT systems can cause organisations to go out of business. Unacceptable use and poor delivery of IT can result in reputation loss that sticks forever.

For the senior IT managers, ‘being monitored’ by the board should be seen as an opportunity to demonstrate wise investment and not be seen as a threat to delivery or innovation. Once the EDM activities are well understood and working efficiently, there should be a clear communication path between the board and the IT senior managers, ensuring that money spent on IT systems and services is invested with discernment and prudence, delivers expected benefits and maintains a compliant and user-friendly working environment.

Guidance through evaluate-direct-monitor activities

The standard usefully concludes with a section demonstrating how the lifecycle activities can be applied to each principle. The activities provide the basis for practice documents aligned with each of the six principles, though they are far from exhaustive. Given that these practices will need to be made organisation-specific, the aim is to provide some working samples that can be expanded upon.