25

The Business Version of Let’s Make a Deal: Is There Enough Upside to Justify All of the Risks?

REMEMBER HOW I SAID that just because you can do something, doesn’t mean that you should? Well you figure out the “should” part by evaluating both the risks and rewards of entrepreneurship. You need to look at the entire picture of how much you can make financially, and what else you are giving up, and decide if there is enough of a trade-off in terms of a big potential payday to justify all of the risks involved in trying to attain it.

Evaluating risks and rewards requires you to do a few things:

- Evaluate how much you are putting on the line in terms of your money, time, effort, and emotions. This means that in terms of money, you need to look at how much of your savings and personal wealth you are investing in your new business (or guaranteeing by using a major asset like a home to guarantee a loan).

- Assess how much you make—or could make—in a job working for someone else, including any benefits.

- Evaluate the opportunity costs of your investment. This means considering what else you could be doing with that money that is now tied up as an investment in your business. This opportunity cost could be a lost investment opportunity (such as putting that money into savings and earning interest on it) or a lost spending opportunity (forgoing a family vacation, new car, or other purchase), or even a lost opportunity to donate to your favorite charitable organization.

These monetary considerations, plus all of the hours you will be working and the stress you will endure, are your risks and issues. These risks and issues need to be evaluated versus the second part of the equation, which is evaluating how much upside potential you realistically could achieve from the business (the reward), based on your thoughtful financial model, assumptions, and level of investment.

The potential rewards of a business opportunity have to significantly outweigh the upfront and ongoing risks you are going to take and the issues you will have to endure for you to be willing to try to reap those rewards. There is no one right answer for everyone to say by how much those possible rewards needs to outweigh the risks and issues, but it needs to be substantial, and it needs to make sense for you. Graphically, you can think of an acceptable risk/reward balance, applied against your personal circumstances as:

POTENTIAL REWARDS > RISKS & ISSUES

Risks and Rewards the Game Show Way

Most investors look at this type of equation for every investment they make using financial benchmarks. For those of you not well-versed in financial terms, such as looking at return on invested capital or cash-on-cash returns, you may find this difficult to do. Therefore, I will turn to an easy proxy for explaining this financial risk and reward evaluation: game shows.

Now, I don’t know why, but I love game shows; I always have. I think I even want to be a game show host in my next life (think Bob Barker, not Vanna White). Game shows are great for demonstrating evaluation and trade-offs. Even though game show contestants don’t have to put up their own money to go on the game show, their evaluation skills are always tested, and there is always something, sometimes something substantial, on the line. No matter what is on the line, even if it is beaucoup bucks, a lot of contestants have an all-or-nothing, borderline gambling mentality. Take, for instance, the hit primetime game show Deal or No Deal.

If you are one of the five people in America who isn’t familiar with Deal or No Deal, it is basically a game of statistics and chance. The way it works is that there are twenty-six suitcases that contain prizes ranging from one measly cent up to one million dollars. There are considerably more “small” prize amounts and just a few “large” prize amounts, all of which are known to the contestants in advance. What the contestants don’t know is which suitcase holds which amount. That is the game. The contestant picks a suitcase to start that contains the prize he will retain if he keeps playing. This suitcase remains closed. Then, the contestant is required to pick other suitcases to be removed from play. As each suitcase is opened, the amount inside is revealed, letting everyone know what prize amounts remain in play (including in the contestant’s chosen suitcase). The hope is that the removed suitcases will contain low prizes, making the chance of getting a high prize much greater.

After every few eliminated amounts are revealed, the show offers the contestant an amount of money to quit the game. The amount is somewhere between the lowest prize remaining and the highest prize remaining, depending on the amounts of low and high prizes left in play. The more high amounts available, the higher the prize offered to the contestant to quit. If the contestant wants to take the offer, he says, “Deal;” if not, meaning he wants to keep playing (thinking he has a bigger amount in his chosen suitcase), then he says, “No deal.” What amazes me (and apparently the people working for the show as well, as I have heard from one of the producer’s brothers) is how many people make poor evaluation decisions. A contestant may be down to seven suitcases, six of which are all worth under $10,000 and one worth $250,000. They are offered $50,000 to quit and they keep going—no deal. They convince themselves that they aren’t risking anything since they came in with nothing. They would rather leave with five dollars and gamble for the $250,000, even though they are in fact risking $50,000 real dollars that would go home with them if they simply said, “Deal.”

If these people were playing Deal or No Deal with their own money at stake somehow, you would hope that they would take the deal more often. However, entrepreneurs often do just that; they say no deal and risk their own money on a business gamble. Whether it is due to poor evaluation skills, a gambling mentality, or something else, potential entrepreneurs poorly evaluate the risk and reward balance of a new business—if they do it at all.

As I said, you may not understand return on investment calculations, but everyone understands Let’s Make a Deal (which, by the way, is one of my all-time favorite game shows). Let’s Make a Deal gives you something, and then you decide whether it is good enough for you or if you want to trade it for something else. That something else could be better or worse than what you already have, so you have to decide if you want to make the trade.

Now, if you were given one dollar to trade for what’s behind one of two curtains and were told that one curtain was worth nothing and one was worth $1,000, would you make the trade? Most of us would. One dollar isn’t a lot to risk for the chance at $1,000, even if the downside is zero. Now, what if you were given $990 and asked to make the same trade—one curtain is zero, the other is $1,000? I hope that none of you would make that trade. You would be risking $990 for a chance to improve your situation by a mere ten dollars, a 1 percent increase. For each one of us, there is a different combination of amounts at risk and potential upside we would be willing to take the risk for, but for everyone, the risk needs to make sense. Certainly, in this case, a 1 percent upside doesn’t make sense when the alternative is losing everything.

Imagine that in the previous examples, the amount you are trading stands for the amount you are investing of your own money in a new business. The two curtains represent the extreme possibilities for your business. You could fail, and it could be worth zero, or you could get the curtain with the big prize. Does the trade make sense? Before you answer that, you have to also factor in your current salary, your time, your opportunity costs, and all of the qualitative risks and rewards, among other things.

Let’s play the game with more concrete numbers. Let’s say that you are making $50,000 a year (plus benefits) at your current job and you have a gadget company that you can start with $60,000 of your own money. You need to evaluate whether you should make a deal. Should you trade your job and the investment for what is behind curtain number two—starting your own business? You don’t always get full information on Let’s Make a Deal, but let’s throw in some additional details. Let’s say curtain number two is a gadget business that sells $300,000 worth of gadgets from each year. Do you trade?

Well I hope you ask Monty Hall for additional information here. Let’s further evaluate the choices. If you are employed, you make $50,000, and you get some benefits on top of that. Now, the $300,000-a-year gadget company may sound exciting because there is that big number there. But remember, that is sales, not profits, meaning that is not what you take home at the end of the day.

To find out what is leftover for you to put in your pocket, you have to take away from sales the cost of making the goods. Then, you have to take away the expenses of sales, marketing and administration, rent, employee salaries, advertising, professional fees, insurance, office supplies, shipping, postage, telephone and fax expenses, website expenses, and interest on any debt the business has incurred, as well as all other expenses, before you know what you are going to make.

The profit a business makes varies by how successful the business is, as well as the industry (e.g., commodity businesses have lower margins—the gross profit for each item after subtracting the direct cost of the product from the sales price of the product, expressed as a percent of the sales price—on average than a similarly branded business and service businesses sometimes have higher margins than product-oriented businesses). However, if you are doing well in this particular business based on the profits of competitors, you would be happy to have a business that has pre-tax profits in the range of 10 percent of sales (we look at pre-tax profits so that you can do an apples-to-apples comparison to your pre-tax salary of $50,000). Ten percent, by the way, is the level of profits that many professional private equity investors consider as a minimum gauge of a healthy mature products business. So, using the 10 percent proxy, that would mean that for a $300,000-in-sales gadget business, the amount available for you to take home is $30,000 (please note that these numbers are just for illustration; many businesses won’t get to $300,000 in sales the first year—if ever—and many businesses aren’t even profitable the first year). This profit ignores (only for this example, do not ignore this in reality!) that you may need to reinvest some of that money to make the business grow next year and the timing of cash flow. It also ignores (again, just for this example) that your perks and benefits from your old job, as with most “benefits” when owning your own business, now come directly out of your pocket.

The 10 percent is a proxy, a litmus test, or “sanity check” if you will, but it provides a good guideline for starting your evaluation. You won’t have perfect information when you start a business, but you still need to sanity check your assumptions to see if they are in the realm of reality.

So, before even considering how the other, non-financial parts of the evaluation (such as the headaches and extra hours) come into play, you are taking a 40 percent (plus benefits) decrease in salary. And this is when you are selling $300,000 worth of gadgets, which is not a number to sneeze at and may not happen the first year. Sure, you say that the business may grow well past that over time and that you may also build equity in the business that you can one day sell at a multiple of several times pre-tax profits. That may be true, so you should evaluate your future business projections versus your current salary, plus any raises you would likely get over the same period of time you project that you will own the business. Even better, look at it over one-, five-, ten- and twenty-year time periods. Don’t forget to take into account the initial $60,000 it cost you to start the business and the loss of using that money for other investments (or for other purposes). You should add in the value of the missed benefits, plus deduct any money that you need to put back into the business (from your pocket) to evaluate the financial trade-off.

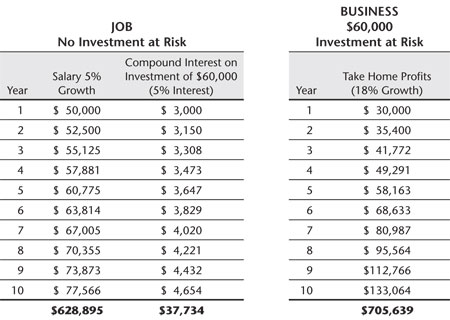

If we look at the chart below and assume that with a starting salary of $50,000 and a 5 percent raise every year, after ten years, you would have earned (pre-tax) almost $629,000. Would you trade that for the chance that the gadget business, which after growing a generous 18 percent per year, might earn you almost $706,000, knowing that the other curtain could contain less than that, even zero? What if you took into account the extra $60,000 in start-up costs that it takes to make that trade? Now, what if you take into account that instead of putting that $60,000 into your business, you could put it into another investment that earns a conservative 5 percent a year on average? After ten years, that interests compounds to earn you another $38,000! If you take that into account, the no-risk scenario earns you both your pay and the interest on your savings, which together is almost $667,000.

If you include your initial $60,000 investment, that brings you to having more than $726,000 at stake, which means that you are risking more than your projected upside from investing in the business. You wouldn’t make that trade based solely on the financial risks and rewards. But a lot of people do, because they never go through this math exercise at the onset.

Salary (with raises) of $628,895 + investment of $60,000 + interest of $37,734 =$726,629 Business after ten years with 18 percent annual profit increase = $705,639

You can see that this evaluation is particular to your circumstances and the opportunity. If you had less salary at risk, a lower investment to make, and a bigger potential opportunity, it may be a better trade for you. Plus, if you can sell the business at the end of the day, that creates additional upside for the rewards side of your equation.

While your projections show a snapshot of the business and can never account for every factor or scenario, they are a good starting point for evaluating if your risk and reward trade-off makes sense. If the numbers don’t work, then you shouldn’t make the trade. No supposed freedom of ownership is worth it if you aren’t making profits.

Given the risks of starting a business and all of the ancillary headaches associated with it, the potential amount you can make from owning your own business should greatly outweigh the amount you can earn from your current job or a similar one. I can’t tell you exactly how much it should outweigh it—that is up to you, but make sure you are comfortable with the reward benefits that you are taking the risk for.

Another way to sanity check yourself is to understand how much you are making per hour. Let’s go back to the $300,000-in-sales gadget company that gives a pre-tax profit of $30,000. That business is going to require a lot of time and effort to get off the ground. There are fifty-two weeks in a year, and let’s outrageously assume that you can actually take two weeks off for vacation (pipe dream!), so you have fifty work weeks a year. While it isn’t uncommon for entrepreneurs to work seven days a week, let’s say you decide to put in long hours during the week to have some free time on the weekends (yeah, right) and so you work five days a week instead. That is five days each week times fifty work weeks, or 250 work days per year.

To be able to take off the weekends, run the business, do the extra paperwork, etc., you are putting in twelve hours a day at work—7 A.M. to 7 P.M. This is probably conservative (fourteen-hour days are more likely), but just for illustrative purposes let’s assume that it is accurate. Twelve hours each day times 250 work days is 3,000 work hours per year.

That year, you take 3,000 work hours to make $30,000 profit (less any money you may need to reinvest in growing the business) from your business with $300,000 in sales. That means, for all of your risk, headaches, and hard work, plus the $60,000 that you have invested of your own money, you are getting paid ten bucks per hour.

And that doesn’t even begin to take into account the opportunity costs of the business. The money you invest in the business can’t earn interest. The time you spend working on the business isn’t spent doing fun things; you may have to forgo vacations, your kids’ baseball games, family events, favorite television programs, or a hobby to be able to earn ten bucks an hour. Does that seem worth it to you? Does risking $60,000 of your hard-earned money that you invested to get the business going, the sleepless nights, the paperwork, managing employees, and working twelve-hour days seem worth the opportunity (because it is not a given that you will achieve your projections) to earn ten dollars per hour? Again, I can’t answer that for you, but likely, you never thought of it that way.

The point is that you need to evaluate what success is and what it requires. You need to understand what you are trading and if it is a fair trade-off. You need to use the hard numbers as a benchmark and then factor in all of the other intangibles before you decide deal or no deal.

Your Business as a Portfolio Investment

One other part of evaluating the risk and reward balance is taking into account diversification. We have all been told that it is important to diversify your investments. You don’t want to have all of your eggs in one basket (sorry for the overused phrase again, but it is really the best one). This is why many stock market investors choose to invest in mutual funds versus picking individual stocks. If you have diversity, one bad investment isn’t going to ruin you financially. It will hopefully be balanced out across your entire fund or portfolio; the really bad will be averaged with the really good and the mediocre, to give you a fair, combined investment return.

When you are starting your business, you are also investing in it. If all of your money is in your business, you will not have the opportunity to diversify with other investments. So, if your business doesn’t do well, all of your eggs will be in a basket that is broken.

It is important for an entrepreneur to show his commitment and have a significant stake in his business. This is a safeguard to ensure that the entrepreneur does everything he can to make the business successful. However, if you are putting every last dime into the business, your eggs will be all in that basket. If I were in that situation, I would want that basket to be bulletproof with fifteen inches of premium padding and a bodyguard to make sure that something didn’t happen to every single one of my eggs.

Evaluating your risks and rewards by doing the entrepreneurial math is one of the most important things you must do before you commit to the entrepreneurial path. This involves looking at the hard numbers and evaluating both quantitatively, as well as qualitatively, what you would give up versus what you may gain. Then, imagine yourself standing in front of two curtains representing the upside and downside possibilities of your new business (to make it more interesting, imagine Monty Hall there with you wearing a plaid jacket from 1962). You are holding the amount of money you will be risking to start the business, including your start-up costs and existing salary. Then, think about the other trade-offs you will have to make. Look at the two curtains before you again. Will you make that deal? Only do it if it is really worth it.

EXERCISE 17

TARGET FOCUS—RISK/REWARD:

Assessing Risk and Rewards from the Numbers

This exercise is comprised of three different evaluations.

A. The financial “deal” evaluation:

- Write down the value of the salary and benefits you would be giving up to start your business. Be sure to include raises and bonuses for each year over the next ten years. If you are unemployed, make an assumption on your next job using reasonable expectations for when you might get the job and the potential salary.

- Next, write down how much money you will personally invest to start and run your new business.

- For any money you plan to invest, write down what other investments you could alternatively invest that money into. What is a reasonable rate of return you can expect to make on that money? If you don’t have a good benchmark, you can look at a range of scenarios (from losing 10 percent to making nothing to gaining 10 percent).

- For any money you plan to invest, write down what will happen if you lose part or all of that investment.

- If you need to take out a loan, write down how much the loan is for and the amount of interest you will be required to pay on that loan.

- Write down what you need to put up in collateral for that investment.

- For any collateral you will need, write down what would happen if you lose that collateral.

- Write down how much you reasonably believe your business will make over the next ten years. Like in number three, look at normal, bad, and good scenarios based on varying the assumptions behind your business.

Now, evaluate if you should you “make the deal” based on the financial merits of the risk and reward trade-off. Do you trade your salary, benefits, investment, and/or collateral for the possibility of making what you may be able to make, purely based on the financial return?

You can first look at the value of item one plus item three above over that ten-year period and compare it to item number eight, taking into account any interest you will have to pay in item five. Is the return big enough to justify the risk? What if you take into account the collateral you have to put up (items six and seven)? Is there a financial merit to the trade-off? If so, how substantial is it? Remember, you probably won’t want to trade $49,000 a year for the chance to make $50,000 a year. If you aren’t 100 percent comfortable with numbers, enlist someone to help you with your evaluation—it is that important!

B. The hourly evaluation:

- Write down how many days a week and hours per day that you think is realistic to achieve your financial model. Find out how many hours per year you will be working. Note: you should interview other entrepreneurs in similar situations for some honest feedback, and take into account all aspects of the business, from marketing to paperwork to customer support to operations (performing the service you provide or making the goods you sell).

- Take the amounts you expect your business to make each year in good, bad, and normal scenarios (from step A8 of this exercise above) and divide each one by the number of hours you will work that year from B1 above. This is your per-hour wage under the different scenarios.

Assess the per-hour wage. Is this a wage that you feel good about and you feel is a good reflection of the value of your time? If not, the reward of your business may not be substantial enough to justify the risk.

C. The prudent investor evaluation:

- Ask yourself if you are “betting the farm” on your business.

- Is the level of investment that you will be making wise, given your financial situation?

- Would you consider making a similar financial investment in any other potential investment?

- Do you have other investments?

- Will you remain diversified from an investment standpoint, or will all of your money be tied up in the business?

- Would you advise a friend or family member (that you like) to take on the same level of financial risk that you will be taking on by starting a business if the roles were reversed?

If you answered yes to items C1 or the second part of C5, or no to the other items, you are not making a prudent financial decision and should reconsider starting a business at a time when your circumstances have changed, so that your Entrepreneur Equation is not out of whack.