Chapter 3: Working with Scenes and GameObjects

Welcome to the third chapter of the book—here is where the hard work starts! In this chapter, we will develop some base knowledge of Unity in order to edit a project. We will see how to use several Unity Editor windows to manipulate our first scene and its objects. Also, we will learn how an object or Game Object is created and composed and how to manage complex scenes with multiple objects using Hierarchies and Prefabs. Finally, we will review how we can properly save all our work to continue working on it later.

Specifically, we will examine the following concepts in this chapter:

- Manipulating scenes

- GameObjects and components

- Object hierarchies

- Prefabs

- Saving scenes and projects

Manipulating scenes

A scene is one of the several kinds of files (also known as Assets) in our project. A scene can mean different things according to the type of project or the way a company is used to working, but the most common use case is to separate your game into whole sections, the most common ones being the following:

- Main Menu

- Level 1, Level 2, Level 3, …, Level N

- Victory Screen, Lose Screen

- Splash Screen, Loading Screen

In this section, we will cover the following concepts related to scenes:

- The purpose of a scene

- The Scene View

- Our first GameObject

- Navigating the Scene View

- Manipulating GameObjects

The purpose of a scene

The idea of separating your game into scenes is that you will process and load just the data needed for the scene; so, if you are in the Main Menu you will have only the textures, music, and objects that that particular scene needs—there's no need to have the Level 10 Boss loaded in random-access memory (RAM) if you don't need it right now. That's why loading screens exist, just to fill the time between unloading the Assets needed in one scene and loading the ones needed in another. Maybe you are thinking that open-world games such as Grand Theft Auto (GTA) don't have loading screens while you roam around in the world, but they are actually loading and unloading chunks of the world in the background as you move, and those chunks are different scenes that are designed to be connected to each other.

The difference between the Main Menu and a regular level scene are the objects (also known as GameObjects) they have. In a menu, you will find objects such as a background, music, buttons, and logos, and in a level you will have the player, enemies, platforms, health boxes, and so on. So, it is up to you and the GameObjects you put in the scene to decide what that scene means for your game.

But how can we create a scene? Let's start with the Scene View.

The Scene View

When you open a Unity project, you will see the Unity Editor. It will be composed of several windows or panels, each one helping you to change different aspects of your game. In this chapter, we will be looking at the windows that help you author scenes. The Unity Editor is shown in the following screenshot:

Figure 3.1 – Unity Editor

If you have ever programmed any kind of application before, you are probably used to having a starting function, such as Main, where you start writing code to create several objects needed for your app, and if we are talking about games, you probably create all the objects for the scene here. The problem with this approach is that in order to ensure all objects are created properly, you will need to run the program to see the results, and if something is misplaced you will need to manually change the coordinates of the object, which is a slow and painful process. Luckily, in Unity, we have the Scene View, an example of which is shown in the following screenshot:

Figure 3.2 – Scene View

This window is an implementation of the classic WYSIWYG (What You See Is What You Get) concept. Here, you can create objects and place them all over the scene, all through a scene previsualization where you can see how the scene will look when you hit Play. But before learning how to use this scene, we need to have an object in the scene, so let's create our first object.

Our first GameObject

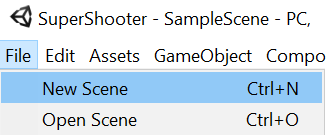

The Unity Universal Render Pipeline (URP) template comes with a construction site test scene, but let's create our own empty scene to start exploring this new concept. To do that, you can simply use the File | New Scene menu options to create an empty new scene, as illustrated in the following screenshot:

Figure 3.3 – Creating a new scene

We will learn several ways of creating GameObjects throughout the book, but now, let's start using some basic templates Unity provides us. In order to create them, we will need to open the GameObject menu at the top of the Unity window, and it will show us several template categories, such as 3D Object, 2D Object, Effects, and so on, as illustrated in the following screenshot:

Figure 3.4 – Creating a cube

Under the 3D Object category, we will see several 3D primitives such as Cube, Sphere, Cylinder, and so on, and while using them is not as exciting as using beautiful downloaded 3D models, remember that we are prototyping our level, also known as gray-boxing. This means that we will use lots of prototyping primitive shapes to model our level so that we can quickly test it and see whether our idea is good enough to start the complex work of converting it to a final version.

I recommend you pick the Cube object to start with because it is a versatile shape that can represent lots of objects. So, now that we have a scene with an object to edit, the first thing we need to learn to do with the scene view is to navigate through the scene.

Navigating the Scene View

In order to manipulate a scene, we need to learn how to move through it to view the results from different perspectives. There are several ways to navigate it, so let's start with the most common one: the first-person view. This view allows you to move through the scene using first-person-shooter-like navigation, using the mouse and the WASD keys. To navigate like this, you will need to press and hold the right mouse button, and while doing so, you can move the mouse to rotate the camera and press the WASD keys to move it. You can also press Shift to move faster and press the Q and E keys to move up and down.

Another common way of moving is to click an object to select it (the selected object will have an orange outline), and then press the F key to focus it, making the Scene View camera immediately move into a position where we to look at that object more closely. After that, we can press and hold the left Alt key and the left mouse button, and start moving the mouse to "orbit" around the object and see different angles to check that every part of it is properly placed, as demonstrated in the following screenshot:

Figure 3.5 – Selecting an object

Now that we can move freely through the scene, we can start using the Scene View to manipulate GameObjects.

Manipulating GameObjects

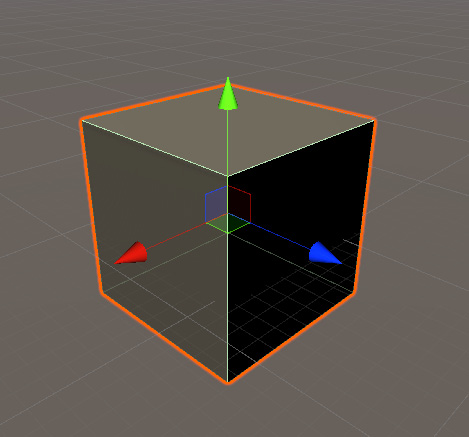

Another use of the Scene View is to manipulate the locations of objects. In order to do so, we first need to select an object, and then press the Y key on the keyboard or the sixth button to the right in the top-left corner of the Unity Editor, shown in the following screenshot:

Figure 3.6 – Changing the transformation tool

This will show what is called the Transform Gizmo over the selected object, which allows us to change the position, rotation, and scale of the object, as illustrated in the following screenshot:

Figure 3.7 – Transform Gizmo

Let's start translating the object, which is accomplished by dragging the red, green, and blue arrows inside the Gizmo´s sphere. While you do this, you will see how the object will be moving along the selected axis. An interesting concept to explore here is the meaning of the color of those arrows. If you pay attention to the top-right area of the Scene View, you will see an axis Gizmo that serves as a reminder of those colors' meaning, as illustrated in the following screenshot:

Figure 3.8 – Axis Gizmo

Computer graphics use the classic 3D Cartesian coordinate system to represent objects' locations. The red color is associated with the x axis of the object, green with the y axis, and blue with the z axis. But what does each axis mean? If you come from another 3D authoring program, this can be different, but in Unity, the z axis (blue) represents the Forward Vector, which means that the arrow is pointing along the front of the object; the x axis is the Right Vector, and the y axis represents the Up Vector. Consider that those axes are local, meaning that if you rotate the object, they will change the direction they face because the orientation of the object changes the way the object is facing. Unity can show those axes in global coordinates if necessary, but for now, let's stick with local.

In order to be sure that we are working with local coordinates, make sure Local mode is activated, as shown in the following screenshot:

Figure 3.9 – Switching between pivot and local coordinates

If you see Global instead of Local as the right button, just click it and it will change. By the way, try to keep the left button as Pivot. If it says Center, just click it to change it.

I know—we are editing a cube, so there is no clear front or right side, but when you work with real 3D models such as cars and characters, they will certainly have those sides, and they must be properly aligned with those axes. If by any chance in the future you import a car into Unity and the front of the car is pointing along the red axis (X), you will need to fix that because our future moving code will rely on that convention, but let's keep that for later.

Now, let's use this Transform Gizmo to rotate the object using the three colored circles around it. If you click and drag, for example, the red circle, you will rotate the object along the x rotation axis. Here is another interesting tip to consider. If you want to rotate the object horizontally, based on the color-coding we previously discussed, you will probably pick the x axis—the one that is used to move horizontally—but, sadly, that's wrong.

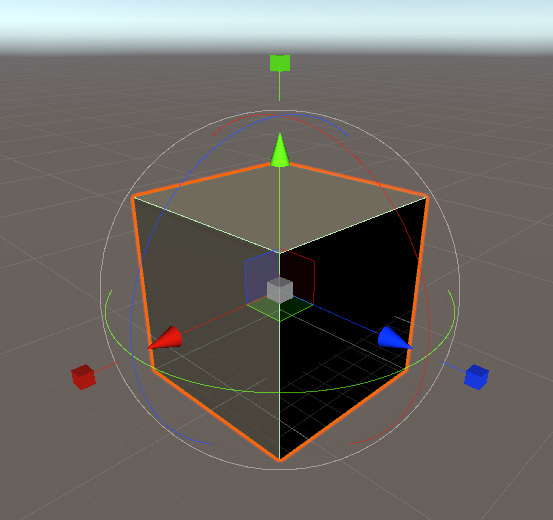

A good way to look at rotation is like the accelerator of a bike: you need to take it and roll it. If you rotate the x axis like this, you will rotate the object up and down. So, in order to rotate horizontally, you would need to use the green circle or the y axis. The process is illustrated in the following screenshot:

Figure 3.10 – Rotating an object

Finally, we have scaling, which is done through the colored cubes on the outer side of the Transform Gizmo sphere. If you click and drag those, you will see how our cube is stretched over those axes, allowing you to change the size of the object. Also, you will have a gray cube in the center of the gizmo that allows you to change the size of the object uniformly along all the axes. The process is illustrated in the following screenshot:

Figure 3.11 – Scaling an object

Remember that scaling objects is usually a bad practice in many cases. In the final versions of your scene, you will use models with the proper size and scale, and they will be designed in a modular way so that you can plug them one next to the other. If you scale them, several bad things can happen, such as textures being stretched and becoming pixelated, and modules that no longer plug properly. There are some exceptions to this rule, such as placing lots of instances of the same tree in a forest and changing its scale slightly to simulate variation, and, in the case of gray-boxing, it is perfectly fine to take cubes and change the scale to create floors, walls, ceilings, columns, and so on, because in the end, those cubes will be replaced with real 3D models.

CHALLENGE

Create a room composed of a floor, three regular walls, and a fourth wall with a hole for a door (three cubes). In the following screenshot, you can see how it should look:

Figure 3.12 – Room task finished

Now that we can edit an object's location, let's see how we can edit all its other aspects.

GameObjects and components

We talked about our project being composed of Assets, and that a Scene (a specific type of Asset) is composed of GameObjects; so, how can we create an object? Through the composition of components.

In this section, we will cover the following concepts related to components:

- Components

- Manipulating components

Components

A component is one of several pieces a Game Object can be made of; each one is in charge of different features of the object. There are several components that solve different tasks, such as playing a sound, rendering a mesh, applying physics, and so on, and even if Unity has a large number of components, we will eventually need to create custom components, sooner or later. In the following screenshot, you can see what Unity shows us when we select a Game Object:

Figure 3.13 – The Inspector panel

In the previous screenshot, we can see the Inspector panel, and if we needed to guess what it does, right now we could say it is showing all the properties of the selected object and that we can configure them to change the behavior of the object, such as the position and rotation, whether it will project shadows or not, and so on. That is true, but we are missing a key element: those properties don't belong to the object; they belong to the components of the object. We can see some titles in bold before a group of properties, such as Transform and Box Collider, and so on. Those are the components of the object.

In this case, our object has a Transform, a Mesh Filter, a Mesh Renderer, and a Box Collider component, so let's review each one of those. Transform just has location information, such as the position, rotation, and scale of the object, and by itself it does nothing—it's just a point in our game—but as we add components to the object, that position starts to have more meaning. That's because some components will interact with Transform and other components, each one affecting the other.

An example of that would be the case of Mesh Filter and Mesh Renderer, both of those being in charge of rendering a 3D model. Mesh Renderer will render the mesh specified in the Mesh Filter in the position specified in the Transform component, so Mesh Renderer needs to get data from those other components and can't work without them. Another example would be the Box Collider. This represents the physical shape of the object, so when the physics calculates collisions between objects, it checks whether that shape is colliding with other shapes based on the position specified in the Transform.

We don't want to explore physics and rendering right now. The takeaway from this section is that a GameObject is a collection of components, each component adding a specific behavior to our object, and each one interacting with the others to accomplish the desired task. To further reinforce this, let's see how we can convert a cube into a sphere that falls using physics.

Manipulating components

The tool to edit an object's components is the Inspector. It not only allows us to change components' properties, but also lets us add and remove components. In this case, we want to convert a cube to a sphere, so we need to change several aspects of those components. We can start by changing the visual shape of the object, so we need to change the rendered model or Mesh. The component that specifies the Mesh to be rendered is the MeshFilter component. If we look at it, we can see a Mesh property that says Cube and that has a little circle with a dot to its right.

Important note

If you don't see any property such as the Mesh we just mentioned, try to click the triangle at the left of the component's name. Doing this will expand and collapse all the component's properties. This is illustrated in the following screenshot:

Figure 3.14 – Disabling a component

If we click it, the Select Mesh window will pop up, allowing us to pick several Mesh options; so, in this case, select the Sphere component. In the future, we will add more 3D models to our project so that the window will have more options. The mesh selector is shown in the following screenshot:

Figure 3.15 – Mesh selector

Okay—it looks like a sphere, but will it behave like a sphere? Let's find out. In order to do so, we can add a Rigidbody component to our sphere, which will add physics to it. In order to do so, we need to click the Add Component button at the bottom of the Inspector. It will show a Component Selector window with lots of categories, and, in this case, we need to click on the Physics category. The window will show all the Physics components, and there we can find the Rigidbody. Another option would be to type Rigidbody in the search box at the top of the window. The following screenshot illustrates how to add a component:

Figure 3.16 – Adding components

If you hit the Play button in the top-middle part of the editor, you can test your sphere physics using the Game panel. That panel will be automatically focused when you hit Play and will show you how the player will see the game. One problem that can happen here is that maybe you won't see anything, and that can happen if the game camera is not pointing to where our sphere is located. The playback controls are shown in the following screenshot:

Figure 3.17 – Playback controls

Here, you can just use the Transform Gizmo to rotate and position your camera in such a way that it looks at our sphere. While you are moving, you can check the little preview in the bottom-right part of the scene window to check out the new camera perspective. Another alternative would be to select the camera in the Hierarchy and use the shortcut Ctrl + Shift + F (or command + Shift + F on a Mac). The camera preview is shown in the following screenshot:

Figure 3.18 – Camera preview

Now, to test whether Physics collisions are executing properly, let's create a cube, scale it until it has the shape of a ramp, and put that ramp below our sphere, as follows:

Figure 3.19 – Ball and ramp objects

If you hit Play now, you will see the sphere colliding with our ramp, but in a strange way. It looks like it's bouncing, but that's not the case. If you expand the Box Collider component of our sphere, you will see that even if our object looks like a sphere, the green box gizmo is showing us that our sphere is actually a box in the Physics world, as illustrated in the following screenshot:

Figure 3.20 – Object with sphere graphic and box collider

Nowadays, video cards can handle rendering highly detailed models (with high polygon counts), but the Physics system is executed in the central processing unit (CPU) and it needs to do complex calculations in order to detect collisions. To get decent performance in our game (at least 30 frames per second (FPS)) the Physics system works using simplified collision shapes that may differ from the actual shape the player sees on the screen. That's why we have Mesh Filter and the different types of Collider components separated—one handles visual shape and the other the physics shape.

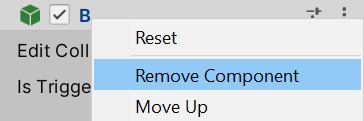

Again, the idea of this section is not to deep dive into those Unity systems, so let's just move on for now. How can we solve this? Simple: by modifying our components! In this case, BoxCollider can just represent a box shape, unlike MeshFilter, which supports any shape. So, first, we need to remove it by right-clicking the component's title and selecting the Remove Component option, as illustrated in the following screenshot:

Figure 3.21 – Removing components

Now, we can again use the Add Component menu to select a Physics component, this time selecting the Sphere Collider component. If you look at the Physics components, you will see other types of colliders that can be used to represent other shapes, but we will look at them later in Chapter 15, Physics Collisions and Health System. The Sphere Collider component can be seen in the following screenshot:

Figure 3.22 – Adding a Sphere Collider component

So, if you hit Play now, you will see that our sphere not only looks like a sphere, but also behaves as one. Remember: the main idea of this section of the book is understanding that in Unity you can create whatever object you want just by adding, removing, and modifying components, and we will be doing a lot of this throughout the book.

Now, components are not the only thing needed in order to create objects. Complex objects may be composed of several sub-objects, so let's see how that works.

Object hierarchies

Some complex objects may need to be separated in sub-objects, each one with its own components. Those sub-objects need to be somehow attached to the main object and work together to create the necessary object behavior.

In this section, we will cover the following concepts related to components:

- Parenting of objects

- Possible uses

Parenting of objects

Parenting consists of making an object the child of another, meaning that those objects will be related to each other. One type of relationship that happens is a Transform relationship, meaning that a child object will be affected by the parent's Transform. In simple terms, the child object will follow the parent, as if it is attached to it. In an example, imagine a player with a hat on their head. The hat can be a child of the player's head, making the hat follow the head while they are attached.

In order to try this, let's create a capsule that represents an enemy and a cube that represents the weapon of the enemy. Remember that in order to do, so you can use the GameObject | 3D Object | Capsule and Box options. An example capsule can be seen in the following screenshot:

Figure 3.23 – A capsule representing a human and box representing a weapon

If you move the enemy object (the capsule), the weapon (the box) will keep its position, not following our enemy. So, in order to prevent that, we can simply drag the weapon to the enemy object in the Hierarchy window, as illustrated in the following screenshot:

Figure 3.24 – Parenting the cube weapon to the capsule character

Now, if you move the enemy, you will see the gun moving, rotating, and being scaled along with it. So, basically, the gun transform also has the effects of the enemy Transform component.

Now that we have done some basic parenting, let's explore other possible uses.

Possible uses

There are some other uses of parenting aside from creating complex objects. Another common usage for it is to organize the project Hierarchy. Right now, our scene is simple, but in time it will grow, so keeping track of all the objects will become difficult. So, to prevent this, we can create empty GameObjects (in GameObject | Create Empty) to act as containers, putting objects into them just to organize our scene. Try to use this with caution, because this has a performance cost if you abuse it. Generally, having one or two levels of parenting when organizing a scene is fine, but more than that can have a performance hit. Consider that you can—and will—have deeper parenting for the creation of complex objects; the proposed limit is just for scene organization.

To keep improving on our previous example, duplicate the enemy a couple of times all around the scene, create an empty Game Object called Enemies, and drag all the enemies into it so that it will act as a container. This is illustrated in the following screenshot:

Figure 3.25 – Grouping enemies in a parent object

Another common usage of parenting is to change the pivot or center of an object. Right now, if we try to rotate our gun with the Transform Gizmo, it will rotate around its center because the creator of that cube decided to put the center there. Normally, that's okay, but let's consider the case where we need to make the weapon aim at the point where our enemy is looking. In this case, we need to rotate the weapon around the weapon handle; so, in the case of this "box" weapon, it would be the closest end to the enemy. The problem here is that we cannot change the center of an object, so one solution would be to create another "weapon" 3D model or mesh with another center, which will lead to lots of duplicated versions of the weapon if we consider other possible gameplay requirements such as a rotating weapon pickup. We can fix this easily using parenting.

The idea is to create an empty GameObject and locate it where we want the new pivot of our object to be. After that, we can simply drag our weapon inside this empty GameObject, and, from now on, consider the empty object as the actual weapon. If you rotate or scale this weapon container, you will see that the weapon mesh will apply those transformations around this container, so we can say the pivot of the weapon has changed (actually, it hasn't, but our container simulates the change). The process is illustrated in the following screenshot:

Figure 3.26 – Changing the weapon pivot

Now, let's continue seeing different ways of managing GameObjects, using Prefabs this time.

Prefabs

In the previous example, we created lots of copies of our enemy around the scene, but in doing so, we have created a new problem. Let's imagine we need to change our enemy and add a Rigidbody component to it, but because we have several copies of the same object, we need to take them one by one and add the same component to all of them. Maybe later, we will need to change the mass of each enemy, so again, we need to go over each one of the enemies and make the change, and here we can start to see a pattern.

One solution could be to select all the enemies using the Ctrl key (option on a Mac) and modify all of them at once, but that solution won't be of any use if we have enemy copies in other scenes. So, here is where Prefabs come in.

In this section, we will cover the following concepts related to Prefabs:

- Creating Prefabs

- Prefab-instance relationship

- Prefab variants

Creating Prefabs

A Prefab is a Unity tool that allows us to convert custom-made objects, such as our enemy, into an Asset that defines how they can be created. We can use them to create new copies of a custom object easily, without needing to create its components and sub-objects all over again.

In order to create a Prefab, we can simply drag our custom object from the Hierarchy window to the Project window, and after doing that you will see a new Asset in your project files. The Project window is where you can navigate and explore all your project files; so, in this case, our Prefab is the first Asset we ever created. Now, you can simply drag the Prefab from the Project window into the Scene to easily create new Prefab copies, as illustrated in the following screenshot:

Figure 3.27 – Creating a Prefab

Now, we have a little problem here. If you pay attention to the Hierarchy window, you will see the original Prefab objects and all the new copies with its names in blue, while the enemies created before the Prefab will have its names in black. The blue in a name means that the object is an instance of a Prefab, meaning that the object was created based on a Prefab. We can select those blue named objects and click the Select button in the Inspector to select the original Prefab that created that object. This is illustrated in the following screenshot:

Figure 3.28 – Detecting Prefabs in the hierarchy

So, the problem here is that the previous copies of the Prefab are not instances of the original Prefab, and sadly there's no way to make them be connected to the Prefab. So, in order to make that happen, we need to simply destroy the old copies and replace them with copies created with the Prefab. At first, not having all copies as instances doesn't seem to be a problem, but it will be in the next section of this chapter, where we will explore the relationship between the Prefabs and their instances.

Prefab-instance relationship

An instance of a Prefab has a binding to the Prefab that helps to revert and apply changes easily between them. If you take a Prefab and make some modifications to it, those changes will be automatically applied to all instances across all the scenes in the project, so we can easily create a first version of the Prefab, use it all around the project, and then experiment with changes.

To practice this, let's say we want to add a Rigidbody component to the enemies so that they can fall. In order to do so, we can simply double-click the Prefab file and we will enter Prefab Edit Mode, where we can edit the Prefab isolated from the rest of the scene. Here, we can simply take the Prefab root object and add the Rigidbody component to it. After that, we can simply click on the Scenes button in the top-left part of the Scene window to get back to the scene we were editing, and now, we can see that all the Prefab instances of the enemy have a Rigidbody component, as illustrated in the following screenshot:

Figure 3.29 – Prefab Edit Mode

Now, what happens if we change a Prefab instance instead? Let's say we want one specific enemy to fly, so they won't suffer the effect of gravity. We can do that by simply selecting the specific Prefab and unchecking the Use Gravity checkbox in the Rigidbody component. After doing that, if we play the game, we will see that only that specific instance will float. That's because changes of an instance of a Prefab became an override, and we can see that clearly if you see how the Use Gravity property of that instance becomes bold in the Inspector. Let's take another object and change its Scale property to make it bigger. Again, we will see how the Scale property becomes bold, and with a little bar at its left. The Use Gravity checkbox can be seen in the following screenshot:

Figure 3.30 – Use Gravity being highlighted as an override

The overrides have precedence over the Prefab, so if we change the scale of the original Prefab, the one that has a scale override won't change, keeping its own version of the scale, as illustrated in the following screenshot:

Figure 3.31 – One Prefab instance with an scale override

We can easily locate all overrides of an instance using the Overrides dropdown in the Inspector, locating all the changes our object has. It not only allows us to see all the overrides, but also reverts any override we don't want and applies the ones we want. Let's say we regretted the lack of gravity of that specific Prefab—no problem! We can just locate the override and revert it. The process is illustrated in the following screenshot:

Figure 3.32 – Reverting a single override

Also, let's imagine that we really liked the new scale of that instance, so we want all instances to have that scale—great! We can simply hit the Apply button, select the specific change, and all instances will have that scale (except the ones with an override), as illustrated in the following screenshot:

Figure 3.33 – The Apply button

Also, we have the Revert All and Apply All buttons, but use them with caution, because you can easily revert and apply changes that you are not aware of.

So, as you can see, Prefab is a really useful Unity tool to keep track of all similar objects and apply changes to all of them, and also have specific instances with few variations. Talking about variations, there are other cases where you will want to have several instances of a Prefab with the same set of variations—as an example, flying enemies and grounded enemies—but if you think about that, we will have the same problem we had when we didn't use Prefabs, so we need to manually update those varied versions one by one.

Here, we have two options: one is to create a brand new Prefab just to have another version with that variation. This leads to the problem that if we want all types of enemies to suffer changes, we need to manually apply the changes to each possible Prefab. The second option is to create a Prefab variant. Let's review the latter.

Prefab variants

A Prefab variant is the act of creating a new Prefab but based on an existing one, so the new one inherits the features of the base Prefab. This means that our new Prefab can have differences with the base one, but the features that they have in common are still connected.

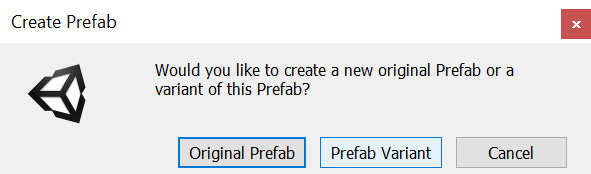

To illustrate this, let's create a variation of the enemy Prefab that can fly: the flying enemy Prefab. In order to do that, we can select an existing enemy Prefab instance in the Hierarchy window, name it Flying Enemy, and drag it again to the Project window, and this time we will see a prompt, asking which kind of Prefab we want to create. This time, we need to choose Prefab Variant, as illustrated in the following screenshot:

Figure 3.34 – Creating Prefab variants

Now, we can enter the Prefab Edit Mode of the variant by double-clicking it, and then add a cube as the jet pack of our enemy, and also uncheck the Use Gravity property for the enemy. If we get back to the Scene, we will see the variant instance being changed, and the base enemies aren't changed. You can see this in the following screenshot:

Figure 3.35 – Prefab variant instance

Now, imagine you want to add a hat to all our types of enemies. We can simply enter the Prefab Edit Mode of the base enemy Prefab by double-clicking it, and add a cube as a hat. Now, we will see that change applied to all the enemies, because remember: the Flying Enemy Prefab is a variant of the base enemy Prefab, meaning that it will inherit all the changes of that one.

We have created lots of content so far, but if our PC turns off for some reason, we will certainly lose it all, so let's see how we can save our progress.

Saving scenes and projects

As in any other program, we need to save our progress. The difference here is that we don't have just one giant file with all the project Assets, but several files for each Asset.

In this section, we will cover the following concepts related to saving:

- Saving our changes

- Project structure

Saving our changes

Let's start saving our progress by saving the scene, which is pretty straightforward. We can simply go to File | Save Scene or press Ctrl + S (command + S on a Mac). The first time we save our scene, a window will just ask us where we want to save our file, and you can save it wherever you want inside the Assets folder of our project, but never outside that folder. That will generate a new Asset in the Project window: a scene file, as illustrated in the following screenshot:

Figure 3.36 – Scene files

We can create a folder to save our scene in that dialog, or, if you already saved the scene, you can create a folder using the Create | Folder option in the Project window and drag the created scene to that folder. Now, if you create another Scene with the File | New Scene menu option, you can get back to the previous scene just by double-clicking the Asset in the Project window.

This only saved the Scene, but any change in Prefabs and another kind of Assets are not saved with that option. Instead, if you want to save every change on the Assets except Scenes, you can use the File | Save Project option. It can be a little bit confusing, but if you want to save all your changes, you need to both save the scenes and the project, as saving just the project won't save the changes on Scenes. Sometimes, the best way to be sure everything is saved is just by closing Unity, which is recommended when you try to move your project between computers or folders. Let's talk about that in the next section.

Project structure

Now that we have saved all our changes, we are ready to move the project between computers or to another folder (if you someday need to). You can close Unity to make sure everything is saved and just copy the entire project folder. If you don't remember where you saved your project, you can just right-click the Assets folder in the Project window and select Show in Explorer (Reveal in Finder on a Mac), as illustrated in the following screenshot:

Figure 3.37 – Locating the project folder

Let's take the opportunity, now that we are in the project folder, to explore a little bit. We will find several folders and files in a full project, but not all the files are necessary to copy in order to move the project elsewhere. The most important folders are Assets, ProjectSettings, and Packages. These folders can be seen in the following screenshot:

Figure 3.38 – Project folder structure

Assets is where all our scenes, Prefabs, and other Asset files will live, so that folder and all its content is indispensable, including those metafiles automatically created per Asset. The ProjectSettings folder contains several configurations of different Unity systems we will fiddle with later in this book, but even if we didn't change any settings, it's always a good idea to bring that folder with us. Packages are a Unity feature that allows you to install official and custom Unity packages or plugins that extend the engine capabilities, this being a new different version of what the .unitypackage files used to be, but let's discuss that later. So far, it's important to note that that folder will have settings about which packages our project is using, so remember to also bring that one with you.

No other folders/files are necessary because some are them are temporary and others can be regenerated, such as Library, where all the converted versions of our Assets will live. By converted, we mean externally generated files, such as 3D models, images, sounds, and so on. Unity needs to convert those files to a Unity-compatible format. The original will live in Assets and the converted ones in Library so that they can be easily regenerated if necessary. Later, in Chapter 5, Importing and Integrating Assets, we will discuss integrating externally generated content.

Now, let's imagine you have compressed those three folders, copied them to a flash drive, and then decompressed the folders into another computer. How can we open the project again? As you can see, a project doesn't have a project file or anything like that—it's just a bunch of folders. In order to open a project, the easiest way would be to find a scene file in the Assets folder and double-click it so that Unity will open the project in that scene. Another option would be to use the Add button in Unity Hub and find the project folder (the one that contains the Assets folder). So, we will add that project to the list of our computer projects, and later, we can just click the name in that list to open it. The following screenshot illustrates this:

Figure 3.39 – Reopening a project

Now, we have all the base Unity knowledge we need in order to start diving into how to use the different Unity systems so that we can start creating a real game! Let's do that in the next chapter!

Summary

In this chapter, we saw a quick introduction of essential Unity concepts. We reviewed all the Unity windows and how we can use all of them to edit a full scene, from navigating it and creating premade objects, to manipulating them to create our own types of objects using GameObjects and Components. We also discussed how to use the Hierarchy window to parent GameObjects to create complex object hierarchies, as well as creating Prefabs to reutilize and manipulate large amounts of the same type of objects. Finally, we discussed how we can save our progress and move the project, reviewing the structure of it and which folders are the essential ones.

In the next chapter, we will learn about the different tools that we will use to create the first prototype of our game's level.