CHAPTER 4

Creating and Capitalizing on Internal Quality—“A Great Place to Work”

What great service leaders know: great service starts with the frontline employee.

What great service leaders do: they hire for attitude, train for skills.

It’s fashionable for CEOs to proclaim that, in their organizations, “people are our most important asset.” In the majority of service organizations, that is literally true. For these firms, people represent by far the largest cost—as well as the greatest opportunity—for differentiation. Employees are the heart, figuratively and literally, of the service profit chain. British historian Theodore Zeldin—who studies the history of work—commented to a reporter that, in the reporter’s words, “the world of work must be revolutionized to put people—rather than things—at the centre of all endeavours.” Zeldin continued: “I remember talking to some CEOs in London. One of them said, ‘We can no longer select people, they select us.’ If we want the best people and we want to attract them, we have to say: ‘What do you want in your job?’ “1

People are motivated by the quality of their jobs and the organizational cultures in which they work. Organizations are known among recruiters, current and prospective employees, and the general public by their “employer brands”—the internal quality of their workplaces. Mark Cuban, owner of the National Basketball Association (NBA) Dallas Mavericks provides an example:

When I bought the Dallas Mavericks in 2000, they were coming off one of the worst stretches in NBA history. . . . One of the first steps we took was to invest in the product. Sure, that means paying more for player talent than most other teams. But we made our investments count in many other ways too. We spared no expense on player facilities, even in the visiting locker room. Players notice these things. Every time another team rolls into town, every player can see what we’ve built, talk to our guys, and file that knowledge away for the future. To refine players’ skills, we also hired the biggest coaching staff in the league. That way, when a big man needs extra work in the post or a point guard needs to work on his ball handling, we’ve got specialized instructors who can take them aside and help develop their skills.2

Cuban was selling his organization to anyone who might be a “buyer”—potential players, employees, fans, and sponsors. It took 11 years, but the strategy apparently worked. Relatively modest expenditures to enhance the quality of the Mavericks’ workplace probably paid dividends in attracting better talent at a more affordable price. It enhanced the quality of entertainment provided to the fans. It raised the esteem in which the organization was held in the community. And in 2011 it paid off in an NBA championship.

Whether the organization is a professional basketball team or a coffee shop, the internal quality of the workplace determines whether an organization is a great place to work. Great places to work tend to be favored organizations with which to do business, leading to profit, growth, or whatever measure of success is appropriate. This is particularly true for a service organization, in which a relatively large proportion of the employees are customer-facing.

How do outstanding employers do it? Knowing that great service starts with frontline employees, great service leaders hire for attitude, train for skills, and make theirs an environment conducive to both. There are one or two organizations in every service industry—even those with the most mercenary reputations, such as financial services—that point the way.

THE VALUE OF WORKPLACE QUALITY AT THE VANGUARD GROUP

Repeatedly, the management of the Vanguard Group of investment funds reminds its audiences that at Vanguard “the investor comes first.” Of course, what financial services firm wouldn’t do that? But at Vanguard, the claim has teeth. The Vanguard Group’s strategy was built by founder John Bogle in 1974 on basic foundation blocks: (1) investment products featuring no-load (no sales charge) mutual funds composed of an index of a group of securities requiring little costly investment management (which has proved to deliver inferior net returns to investors more often than not), (2) efforts on every front to minimize costs that eat into long-term mutual fund returns, and (3) policies that discourage short-term trading and encourage long-term investments by loyal customers.

If the investor comes first, however, where does that leave employees, especially in an organization with a penchant for cutting costs?

Workplace Quality Yields the Right Employees

Vanguard puts the investor first by addressing the well-being of “crew members”—the term used instead of “employees” in a culture based on the values of Lord Horatio Nelson of the HMS Vanguard and British nautical fame. In addition to a comfortable, functional working environment in a suburb of Philadelphia, it also requires a set of values, policies, and practices of crew members. In particular, Bogle cites trust as a building block for the organization, as well as the need for leaders “at times of decisions” to “make contact with foundational convictions and with a sense of calling which comes from going deep within oneself.”3

As anywhere, workplace quality starts with hiring. Vanguard looks for new crew members who have a sensitivity to customer needs but also who lean to the careful and conservative side in making investment decisions, and understand and sympathize with the need for frugality. Employee buy-in to the objectives of the organization is important. The central theme at Vanguard is, according to Bogle, stewardship. From the beginning, he set out a “solid system of human and ethical values” that include “integrity, discipline, honesty, quality, ambition, loyalty, competition, creativity, innovation, cooperation, continuity, even a sense of humor—in all, the character of our company.”4

The work environment at Vanguard has fostered a high degree of loyalty among employees, which is of critical importance in an organization with a strategy focused on investor loyalty.

Careful Selection of Employees and Customers Pays off: the Case of Mabel Yu

The careful selection of crew members has paid off handsomely at Vanguard. This was brought to our attention by an episode told and retold after the Great Recession of 2008.5

The story involves a recently hired investment analyst, Mabel Yu, who was assigned to examine the most credit-worthy (AAA-rated) derivative securities backed by mortgages and other debt that were being assembled by the most highly regarded investment bankers for resale to the public, pension funds, and mutual funds like Vanguard. Yu, a product of the careful Vanguard hiring process, could not assess the quality of the assets behind these derivatives and therefore couldn’t understand what was being offered. As a result, she began recommending against derivatives as investments, and suffered the condescension and ridicule of her counterparts on Wall Street, many of whom couldn’t adequately explain the nature of the securities either. Her management at Vanguard, who were hired by the same careful process, stood behind her. As a result, they passed up some hot issues and in the process endured returns lower than competing funds that were buying the offerings. That happened only until the US economy and the assets underlying many of these securities blew up in 2008, leaving Vanguard’s customers with losses much smaller than those for many of its competitors. Vanguard, both because its investors own it (through a mutual form of ownership) and because of its conservative investment practices, required no bailout. Of greater importance for crew members, Vanguard didn’t lay anyone off during one of the worst economic downturns in the past 80 years.

The overall result for investors over a longer period has been good as well. Vanguard’s index funds, designed to produce investment results that are only an average for a bundle of securities, nevertheless often rank high among their peers on net returns to investors because of the low costs charged against individual account balances. Of perhaps greater interest for us, however, are clients’ perspectives on Vanguard’s services. Even though the typical Vanguard client requires little direct contact with the company, Vanguard regularly leads the mutual fund industry in investors’ ratings of its services. The ratings are given particular validity by the fact that fully one-third of Vanguard’s investors also have funds at its nearest competitor and can compare services directly.

As we can see from the Vanguard example, great employers have a clear and often inspiring mission. Even more important, they have a culture—a set of values, behaviors, measures, and actions—that is designed to ensure that the mission and its supporting strategy are both achievable and achieved. Most importantly, great places to work are often high-trust environments; high levels of trust enable an organization to do things faster, with greater confidence, and more profitably. Vanguard’s management trusted Mabel Yu’s judgment. Mabel Yu was secure enough in her job to make difficult decisions on her own.

ALIGN MISSION, CULTURE, AND EXPECTATIONS

The process of fostering great places to work, characterized by high-trust environments, starts by aligning the organization’s mission and culture with the expectations of prospective employees. It helps if the organization has an impeccable global reputation. But global reputations don’t just happen. They are the result of a clear mission, a performance-based culture, and a well-thought-out process for shaping and addressing manager and employee expectations.

Take the Mayo Clinic, one of the world’s best-known medical institutions, for example. The Mayo Clinic is where patients from all over the world go for the treatment of complex ailments. Much of its fame is spread by former patients. Mayo patients talk. According to Mayo’s estimates, on average each former patient tells 40 other people of his or her experience. Each one is estimated to generate about five new patients. One survey found that 85 percent of the Clinic’s patients recommend that someone go there. That’s real “ownership” behavior.6

For medical practitioners and staff, employment at the Mayo Clinic is prestigious. Its mission and “business” are the topics of conversation at parties. A job there wins admiration from others and is a source of self-satisfaction for associates. Still, that doesn’t mean that recruiting new hires at the Mayo Clinic is easy. Like all organizations with a strong culture, the Mayo Clinic is not for every professional. It appeals to the team player, not the entrepreneur or aspiring star and millionaire. In a sense, everyone is a star at Mayo, but there, stars have to put their egos aside while working with others as a team.

Mayo is well known among medical practitioners, who either are enthusiastic about working there—or avoid even the idea of it. Doctors contemplating careers there know that they have to be prepared to show, by their attitude and the quality of their diagnoses and treatments, that they put the patient first, schedule their work around the patient rather than vice versa, and stand ready to share administrative duties from time to time. The clinic’s research is conducted with a similar philosophy of interdisciplinary cooperation. While the organization may not reward its researchers on a star system, it has nevertheless produced remarkable research results, including the Nobel Prize for the development of cortisone, something that may have been impossible without the contributions of a number of professionals.

The Mayo Clinic manages the fit between mission, culture (values and behaviors), and employee needs carefully. Organizations seeking to capitalize on an effective culture start by finding out what the “right” prospective employees want, then come up with a human resource strategy that meets those needs, involve existing employees in the process of making the deal (establishing mutual expectations), and live up to the expectations created.

Sensitize Managers to What Employees Want: Internal Service Quality

If trust has significant bottom-line value and results from expectations that are met, we need to know the expectations that employees have for a job. We know from the research of others that customers’ satisfaction depends on whether their expectations are met or exceeded.7 The same goes for employees.8 Great service leaders not only understand the expectations that form the basis for employee satisfaction and engagement but use that knowledge to inform management behaviors. Such an understanding can also provide the basis for altering expectations, finding a good fit between what employees want and what management can deliver.

What Employees Want. Service Management Group (SMG) periodically analyzes data on the service profit chain from the more than 20 million surveys it collects annually from employees and customers of more than 100 clients in the retail, restaurant, and service industries—a veritable treasure trove of information. Its analyses have consistently identified several aspects of management that are strongly correlated with employee engagement and loyalty, as well as outcomes such as employee satisfaction, customer loyalty, and sales.

The study by Service Management Group found that employees credit three management behaviors with having the greatest impact on their satisfaction, engagement, and loyalty:9 (1) my supervisor is involved in my development, (2) my supervisor cares about me, and (3) my work is appreciated, in that order. Next is the amount of training received on the job, followed by how well the employee’s team works together.10 This study also found that management skills and behaviors are much more important in influencing employee satisfaction than policies and procedures.

A number of other studies have suggested other things that employees look for on a job:

1. A boss who’s fair. Employees apparently judge fairness in terms of whether or not a manager hires, recognizes, and fires the right people. This suggests that every personnel decision made by a manager is judged by a jury of those who report to her. Where such personnel decisions are left to self-managed teams, they serve as judge and jury.

2. Opportunities for personal development. Employees are interested in self-betterment. They want both access to job training and paths to positions with greater responsibility.

3. Frequent and relevant feedback. Employees increasingly prefer this type of feedback as opposed to the traditional annual review. This preference has a lot to do with the mentality of Millennials—those who have reached employment age after the year 2000—who exhibit a strong interest in personal development as opposed to immediate monetary gain. They are more confident than their predecessors that they’ll be paid adequately throughout their working lives.

4. Capable colleagues on the job. Winners like to work with winners, but they don’t like to work with losers. In fact, if managers are not sufficiently adroit at disengaging poor performers from the organization, winners will leave.

5. Latitude (within limits) to deliver results to valued customers. Latitude is of particular importance in service delivery, where unpredictable events requiring judgment and fast response are the order of the day. Employees need to know just how much latitude they have; it can be described in terms of the limits within which they appear to be comfortable in their jobs. A clear exposition of both latitude and limits is important.

6. Reasonable compensation. Employees exercise good judgment about what is reasonable. While an organization can’t stray far from what is perceived as reasonable, employees’ expectations regarding compensation are often surprisingly modest.11

One of the most extensive studies of the subject found that of the items on the list, just three caused nearly two-thirds of variation in employee satisfaction levels: (1) latitude (within limits) to deliver results to valued customers, (2) the authority given to employees to serve customers, and (3) the ability, gained in part through knowledge and skills gained on the job, to deliver results to customers.12

Why It Matters. If you recall, the Service Management Group study cited earlier found that as employee turnover increases, customer-satisfaction levels decline. Stores with the highest employee turnover are found to have the lowest overall customer-satisfaction scores. A significant relationship exists between the proportion of employees remaining on the job 12 months or more (remember, these are retail service jobs) and customer loyalty. More importantly, customer loyalty is significantly related (statistically) to 12-month comparative (year-to-year) sales increases.13

Shape and Meet Expectations: The Job Preview

For managers, understanding what employees want provides a basis for setting expectations for service jobs. Buckingham and Coffman have concluded that great managers make few promises to their employees but keep the ones they do make.14 This kind of no-surprises management is the basis for the trust that makes execution easier.15 It reduces management time and effort required in the implementation of changes in policies and practices.

Prospective employees form expectations about an organization from a variety of sources, including the organization’s reputation, the actions of its leaders, the way its employees speak about it, its advertising and public relations, and of course the quality and value of its products and services. These sources of information are largely impossible to control. Given the so-called transparency afforded by new technologies, the best assumption is that the truth about an organization’s values, beliefs, and behaviors will come out, for better or worse. An organization is advised, then, to encourage leaders to practice in a manner by which they would like to be judged.

Attracting potential employees to an organization under false pretenses, whether intentionally or not, simply doesn’t make economic sense. Often doing so only promises misalignment, poor performance, and disengagement at a later date, all of which can be costly in both economic and psychological terms. As a result, the most effective communicators of the internal brand go beyond portraying the values, beliefs, and behaviors clearly to prospective employees. They also provide job previews—descriptions of jobs in their most attractive and unattractive terms during the recruiting process. Research suggests that job previews reduce employee defections and turnover by alerting prospective employees in advance to what to expect on the job. A preview, according to one interpretation, “vaccinates” people against disappointment.16 Job previews have even been shown to be effective in improving retention after employees are hired. Job previews, according to one interpretation of this finding, inform new employees that what they are experiencing—irate customers, customer questions they can’t answer, and so forth—is normal and just part of the job, not something to be overly concerned about.17

Measure and Take Timely Action on Nonbelievers

Cultures evolve by themselves without efforts by leaders to shape them. Still, culture building is not a process best left to chance. It requires a constant attention to behaviors that adhere to or violate values. Measurement of behaviors too often is neglected, subject to management “feel,” and therefore subjective. Worse yet, these measures are often put aside when they identify managers who are nonbelievers in the culture—those not managing by the values, disruptive to the culture, and enabling counterproductive behaviors among their direct reports. This is especially true when the individual is a good producer, someone who “makes the numbers.” Corrective action, whether it involves coaching or dismissal, is not something that many managers enjoy; as a result, they tend to put it off much too long.

The most frequent complaint we hear about managers is that they fail to take timely action to deal with those in leadership positions who can’t manage by the values of the organization, regardless of their ability to meet bottom-line goals. Invariably performance improves when nonbelievers—or those simply incapable of managing by the values—are let go. Results from those remaining in the organization more than make up for those of the departed “good producer.”18 For example, Mayo Clinic gives a personnel committee responsibility for addressing problems with physicians who are not living up to the clinic’s values or not “exhibiting respectful, collegial behavior to all team members. Some physicians have been suspended without pay or terminated.”19 This is essential to preserving this organization’s culture.

HOW THE PROS MAINTAIN GREAT PLACES TO WORK

Cultures that foster high-trust environments provide the context for great places to work. But unless managers implement policies and practices that reinforce productive cultures on a day-to-day basis, internal quality can decline. Fortunately, we’ve had a chance to observe the best in action—and their policies and practices fit into clear patterns. The managers in each case may not reflect every behavior described here, but they invariably include most.

What we present here is a recipe, not a menu. Discipline is required in the order in which the “ingredients” are implemented.

Hire for Attitude

High-performing organizations invariably sort out prospective employees on the basis of whether they (1) are interested in the business, (2) are passionate about the mission, (3) relate to the organization’s values, and (4) are comfortable with the behaviors associated with the values, in other words, “how we do things around here.” We call that hiring for attitude. For example, at Lululemon Athletica, the manufacturer and retailer of workout clothing, those who are not passionately interested in personal fitness need not apply. According to its website, the company seeks to build “a community hub where people [can] learn and discuss the physical aspects of healthy living . . . as well as the mental aspects of living a powerful life of possibilities.”20 As if that were not definitive enough, the company “has a mission-oriented business model and expects its employees to have detailed personal and professional growth plans that are shared with other employees.”

A word of caution is appropriate here, and Lululemon’s leadership helps illustrate it. Organizations that are successful in hiring for attitude, as we’ve described it here, often foster in their members a great deal of pride in what they do. That pride can morph into arrogance, particularly toward customers. It’s the role of leadership to make sure that doesn’t happen. Unfortunately, that’s not what happened at Lululemon when Chip Wilson, the company’s founder and CEO, apologized to employees for introducing a fabric that, when stretched too tightly, became transparent, causing many customer complaints. Unfortunately, his apology was perceived as blaming customers, particularly those too large to fit comfortably in Lululemon’s apparel, for the problem. Wilson’s behavior was not surprising, given the strong emphasis on personal pride at Lululemon. However, customers who perceived his remarks as an insult ensured his early departure as CEO.21

Among those who strongly identify with a company’s business, mission, and values, some candidates can exhibit the behaviors and some can’t. A second screen is necessary for traits such as empathy, desire to work in teams, and other qualities critical to the effective delivery of outstanding service. Once issues of attitude have been resolved, other factors contribute to great places to work.

Train for Skills

Organizations know how to train for skills much more effectively than for attitudes. The training often starts with “how we do things around here.” In organizations such as Google, it doesn’t go much further than that. But other organizations may require more task-specific training. At Intuit, for example, subsequent training on the job may include the kind of education regarding both the company’s tax software and the tax codes necessary for customer-service representatives in service centers to do their jobs effectively. This is followed by extensive observation and practice taking phone calls and responding to Internet messages. This training regularly includes the engineers who designed the software, because they are expected to take customer calls periodically to obtain information about improvements in their products.

Provide Effective Support Systems

Support systems—technology, networks, facilities, information systems—can be designed that (1) help make employees winners or losers in the eyes of their customers and (2) help make employers winners or losers in the eyes of their employees. Whereas solid support systems make things easier and better for employees and customers, technology requiring frequent maintenance, airline networks with poor connections and poorly designed or laid-out facilities make work harder for employees while negatively affecting customer service. While it’s important to mention support systems here as part of creating a great place to work, we’ll have much more to say about them in chapter 6.

Provide Latitude (within Limits) to Deliver Results

Too many managers assume that the key to creating a great place to work begins with more delegation and accountability. Nothing could be further from the truth. Only after having established a high level of alignment between the organization, managers, and their employees by setting expectations, selecting the right people, training them well, and providing them with effective support systems do organizations with great workplaces begin to expand the latitude given to frontline employees to use their judgments in delivering results. The sequence is clear: align expectations, hire for attitude, train for skills, provide effective support systems, and then extend latitude for decision making on the job.

Of course, latitude without limits can lead to anarchy. Employees prefer clarity on the limits under which they work. These limits can be explicit or implicit (“how we do things around here”). For example, the Ritz-Carlton organization gives its frontline employees, including housekeepers, the latitude to commit up to $2,000 in resources to correct a customer’s concern on the spot rather than letting it fester into a bigger issue. Just the knowledge that they have the latitude conveys a sense among frontline employees that they have the support of their organization.

At Southwest Airlines the rule is “do whatever you feel comfortable doing for a Customer.” It’s up to the Southwest Employee (remember, at Southwest Airlines, Employee and Customer are always capitalized) to use judgment in deciding what is appropriate in a business in which quick thinking and action is important. This is illustrated by the following true story: A middle-aged man in a wheelchair approached a Southwest counter with a valid ticket. The agent immediately noticed, however, that the man was dressed in dirty, torn clothing and gave off a strong odor. Allowing him to board the airplane would create discomfort for other passengers; it was out of the question. Not boarding the passenger could possibly be grounds for a lawsuit. The agent had to think and act fast.

What would you do if you had no more than 10 seconds to react? What the agent did is a reflection of the care with which she was selected, trained, and given the latitude (within limits) by management to use good judgment. We’ll pick up the story later in the chapter.

Extend Latitude to Include Firing Customers

The ultimate act of increasing delegation and latitude is that of granting authority to frontline employees to fire an occasional customer for good cause. Even though it’s controversial, many outstanding service providers practice the art of firing customers. It is a way of correcting mistakes that result in the selection of customers who are rude or demeaning to employees or to other customers. It demonstrates to employees that management stands behind them. The following report of one such firing at jm Curley, a Boston restaurant, is illustrative:

When a customer recently plunked a $20 bill on a table and told his server that he would deduct a dollar from the potential tip each time something went wrong, [jm Curley] restaurant manager Patrick Maguire took the man aside and explained—in so many words—that he was treating the wait staff like dirt. Maguire packaged up the entrees and escorted the man and his date from the restaurant.22

Restaurants aren’t the only organizations that are firing customers, either. ING Direct, a provider of online banking services designed to deliver great service at low cost (acquired by Capital One), used to suggest to several thousand customers a month that they transfer their accounts elsewhere, simply because the company was not designed to meet their apparent need for frequent and extensive telephone or online service.

We can draw several conclusions from the sample of firms we’ve observed firing customers:

1. Employees immediately associate management’s actions with a good place to work.

2. These practices take place in organizations with high employee engagement and loyalty.

3. Firings are generally viewed favorably by other customers for whom the service was designed.

4. Rarely does a fired customer complain to others about his experience.

5. Most often, fired customers not only are chastened but ask to be forgiven and served again. At jm Curley’s, the restaurant cited earlier with the rude patron, the customer, when asked by the manager to leave, “became contrite, insisting on making a face-to-face apology to the server. Maguire (the manager) then reseated the couple. . . . And in the end, the patron left a 40 percent tip.”23

All of this assumes, of course, that the fine art of customer firing is practiced well. This involves

1. Establishing clearly defined processes

2. Making sure that middle managers are involved and on board

3. Advising employees that the practice is implemented only in clear and extreme cases

4. Explaining unacceptable behaviors clearly to customers

5. Accepting some responsibility for the mismatch between customers and the organization (as at ING Direct)

6. In most cases, handling the situation as quickly and quietly as possible—but with the full knowledge of affected employees

New technologies will make firing customers both easier and less discriminating. New smartphone apps, for example, don’t just enable customers to rate service providers. At Uber and Lyft, the Internet-based personal transportation services, drivers rate their passengers too.24 Passengers receiving low ratings may find that the quality of the service they receive declines; fewer drivers will be willing to respond to their calls. While this feature places more authority in the hands of drivers, it also takes control over quality out of the hands of management. Whether this form of delegation will have a positive impact on service quality remains to be seen.

Calibrate Transparency

Open, two-way channels of communication contribute to no-surprises management, as well as the trust that follows. But transparency requires a policy regarding the amount and kind of information that will regularly be shared within the organization—one befitting the culture and strategy of the organization. Will limits on sharing be determined by what top management thinks employees “need to know”? Or will employees be allowed to pick and choose from a larger information base according to what they think they need to know? Vineet Nayar, vice chairman and joint managing director of HCL Technologies, a large India-based provider of information technology services, has a definite opinion on the subject:

All HCL’s financial information is on our internal Web. We are completely open. We put all the dirty linen on the table, and we answer everyone’s questions. We inverted the pyramid of the organization and made reverse accountability a reality. . . . So my 360-degree feedback is open to 50,000 employees—the results are published on the internal Web for everybody to see. And 3,800 managers participate. . . . [Comments are] anonymous so that people are candid.25

In another venue Nayar said, “We are trying, as much as possible, to get the manager to suck up to the employee. This can be difficult for the top twenty or so managers whose ratings are posted. As one put it, ‘It was very unsettling the first time.’”26

This degree of transparency may not be appropriate for all organizations and managers, but it has proved effective as a guideline in hiring and recognizing managers, fostering employee morale, and improving employee retention in a company that finds itself in a competitive labor market. Nayar and his organization have asked and answered important questions as part of an effort to establish a high level of trust.

Organize for Team-Based Work and Teaming

Many organizations that deliver outstanding service are organized around teams—and this is no coincidence. Team-based organizations have the advantages of making the workplace seem smaller than it really is, thereby enabling large organizations to deal with issues of scale and its negative effects on culture. They support notions of self-management as team members exert peer pressure on one another to do the right thing. Teams, particularly those with diverse members, are often more creative than individuals working alone.27

Amy Edmondson has coined the word teaming to describe the phenomenon of a group of people hired for their ability to work with others—to team—who come together to achieve a specific result, then move on to their next assignment with new team members. This is typical of what happens in the delivery of many services. As Edmondson puts it, “Teaming is a verb, not a noun.”28

The effective deployment of teams—however narrowly or broadly defined—imposes certain responsibilities on management. Richard Hackman researched this and concluded that the successful deployment of teams requires that they have (1) a clear and compelling direction, (2) well-designed tasks, (3) norms that are enforced, (4) sufficient coaching in team processes, (5) a clear understanding of who belongs to the team, and (6) a team-based rewards system.29We’ll have more to say about the last item later.

Create the Foundation for a Self-Controlling Organization

Teams can provide the foundation for self-control by employees that enables an organization to minimize traditional managerial inputs. As chairman and CEO of Taco Bell, John Martin discovered this when he concluded that he couldn’t find or afford enough Taco Bell managers to staff his aggressive growth plans some years ago. Out of necessity as much as the desire to innovate, the company organized some of its units around self-managed work teams sharing a manager with several other units. With the proper training, such teams were able to carry out their own hiring, training, cash management, and problem solving. Invariably, they delivered better customer service ratings than units with dedicated managers.

We often think of control as the process of setting targets, measuring performance against those targets, recognizing those who meet the targets, and taking corrective action with those who don’t. This process is not one of management’s more pleasant and rewarding tasks. Just ask a manager attempting to complete an employee’s annual review. In great places to work, leaders try to do something about this.

Integrate Control with Learning and Reflection. There is a trend toward replacing annual reviews—the traditional cornerstone for performance measurement and review—with ongoing observation and coaching. It is in part a response to the demands of a new generation of leaders and employees who typically value personal development and frequent feedback regarding their work (and sometimes their personal affairs) more than money. Frequent feedback has proved to work at all levels of a service organization.

A variation on this practice is the “team huddle” prior to every shift at a Caesar’s Entertainment casino. The 10-minute meeting, on company time, returns many times the cost: employees have higher levels of problem awareness (what went wrong yesterday, what we need to do to ensure it doesn’t happen today, information about the business, and so forth), development, and satisfaction, all of which lead to better customer service and more loyal employees.

A recent study measured the economic impact of the practice of allowing employees 15 minutes at the end of each day to reflect on their work and ways of improving it.30 After testing the idea with students, these researchers replicated their study at Wipro, a large India-based business-processing outsourcing company. In the test group, Wipro set aside 15 minutes at the end of each work shift to allow employees to reflect on lessons learned that day. The test group exhibited a more than 20 percent increase in performance—even allowing for the fact that individuals in the control group were at their jobs 15 minutes more each day.

All of these practices suggest that for employees, time on the job devoted to preplanning or end-of-shift reflection may be more important than what we have traditionally thought of as work.

Staff and Organize for Self-Control. Organizational devices that foster learning and self-control have a powerful effect on the quality of the workplace. Foremost among these, as we have seen, are teams and teaming. To be successful, organizations carefully recruit people who are comfortable with getting more direction from peers than from the top. Working for Google, an organization that relies on people who are able to provide their own direction, is not for everyone. Remember also what we saw at Whole Foods Market: team-based incentives, recognition, and rewards matched with policies of transparency regarding information and teams with wide latitude to take charge of their own fate and exercise the corrective action necessary to achieve success. This team-based organization relieves management of some of its most distasteful tasks while better realizing the control function.

Emphasize Nonfinancial Measures and Balanced Scorecards

If the best predictors of future service success are nonfinancial measures such as employee and customer loyalty, engagement, and ownership, then organizations will find that it makes sense to highlight them in setting goals and measuring performance. A service organization can measure performance by a mix of financial and nonfinancial measures in a way that is both logical and effective. As we pointed out in chapter 3, the service profit chain lends itself naturally to the tracking of performance by means of employee, customer, and financial measures—a balanced scorecard.31 These measures need not be equally weighted. Employee engagement, loyalty, and productivity measures may be among the most important ones on the balanced scorecards because much of service organization performance is driven by employees.

Decide on a Low- versus High-Retention Strategy

Management of service activities offers a fertile field for implementing basic notions about why people work. Leaders can choose from an underlying rationale for two basically different human resource strategies, one involving high and one involving low employee-retention rates. Basically, they can ask whether an organization functions more effectively with fewer, better-trained, better-paid people, or the opposite. The answer depends on the importance of such things as service quality and customer loyalty in achieving an organization’s goals.

Our anecdotal, case-based research has led us to a point of view, summed up in a comment made by David Glass when he was CEO of Walmart. Our recollection of it is “Give me fewer, better-trained, better-paid people and they’ll win every time.”32 Our views on the choice are best expressed in the names we have in the past attached to the low-retention strategy (a cycle of mediocrity)33 and the high-retention strategy (a cycle of success). But let’s be clear: both can be winning strategies if they are pursued relentlessly with a logic that is internally consistent.

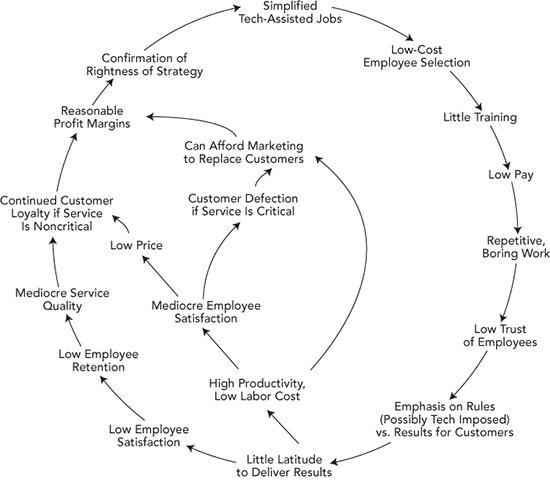

The Logic of a Low-Retention Strategy. At the core of a low-retention strategy are simplified jobs, limited attention to selecting from a pool of job applicants, little training, and relatively low pay (figure 4-1). All of these practices, when combined with reasonable productivity resulting from practices that may be a reminder of the Taylorism movement of the early twentieth century,34 can result in low prices that will appeal to certain customers. The results may be repetitive, boring jobs that have been designed to accommodate a low skill level; relatively low levels of employee satisfaction; a poor attitude in the service encounter; high turnover; and relatively poor service quality. But employees can be replaced at relatively low costs of selection and training. If the service is regarded by customers as noncritical, they may not defect. The outcomes for the organization are relatively low costs from lost business, reasonable margins, and acceptable profits. All of this can lead to the conclusion that the strategy is working.

Still, the consequences of this strategy may also be a low-quality service encounter, a high rate of customer turnover, a high level of customer dissatisfaction, substantial effort devoted to replacing departing customers, and a lack of continuity in customer relationships. These are costs that are frequently ignored in economic analyses of low-retention strategies. In the wake of the adoption of the Affordable Health Care Act in the United States, for example, many employers are opting for a larger proportion of jobs with less than 30 hours per week of work—the point at which health benefits have to be provided. This will inevitably lead to a higher rate of turnover among customer-facing employees. In some cases, this low-retention strategy will lead to unintended, adverse results.

Figure 4-1 The Logic of a Low-Retention Strategy in Services

Source: Adapted from Figure 1, “The Cycle of Failure,” in Leonard A. Schlesinger and James L. Heskett, “Breaking the Cycle of Failure in Services,” Sloan Management Review, Spring 1991, pp. 17–28, at p. 18.

The Logic of a High-Retention Strategy. The second of these strategies, one that we originally thought of as “the cycle of success,” is designed for relatively complex jobs requiring employee judgment (figure 4-2). This strategy entails careful employee selection, extensive training, and above-market pay, all of which can lead to relatively high labor-associated cost. It requires the delegation of a great deal of latitude to the employee to deliver results to customers, a factor that is thought to lead to relatively high service quality and high loyalty among customers who regard the service as critical. It leads to fewer costly defections of customers. It may influence customers to help with the marketing effort to new customers by providing referrals, thus reducing marketing costs. Other customers, who do not regard the high quality of service worth paying for, may depart. They are not replaced, again avoiding unnecessary costs of marketing.

Figure 4-2 The Logic of a High-Retention Strategy in Services

Source: Leonard A. Schlesinger and James L. Heskett, “Breaking the Cycle of Failure in Services,” Sloan Management Review, Spring 1991, pp. 17–28, at p. 19.

High costs of selection, training, and wages for employees may be offset by high levels of employee loyalty, which are also critical to the delivery of high-quality service.

All of this results in the retention of targeted customers (as well as the loss of those not targeted), reasonable margins, and confirmation of the rightness of the strategy. Note that the primary objective here is a high retention rate. It is seen as an element in a purposeful strategy to retain customers and the profit they bring.

One result of this strategy is reasonably high productivity delivered by loyal employees to offset high wage rates. When it works, it results in lower overall labor cost/sales ratios. On other occasions it may require premium prices to defray higher costs while maintaining profit margins.

Case Example: Costco versus Sam’s Club. The irony of David Glass’s comment when he was at Walmart is that his organization has not followed the high-retention strategy while one of its competitors, Costco, has. At Costco, the starting wage at the time we write this is about 40 percent above the national minimum wage. Average wages are nearly three times the minimum wage. In commenting on the policy and advocating an even higher national minimum wage, CEO Craig Jelinek said,

At Costco, we know that paying employees good wages makes good sense for business. We pay [high starting wages] . . . and we are still able to keep our overhead costs low. An important reason for the success of Costco’s business model is the attraction and retention of great employees. Instead of minimizing wages, we know it’s a lot more profitable in the long term to minimize employee turnover and maximize employee productivity, commitment and loyalty.35

An analysis several years ago of the Costco strategy compared with that of Walmart-owned Sam’s Club, a direct Costco competitor, supports Jelinek’s argument.36 Its author, Wayne Cascio, attempted to cost out the turnover of employees for the two chains. He concluded that added costs of recruitment, training, and lost productivity from a low-retention strategy far outweighed the costs of paying higher salaries under a high-retention strategy. He found that even though Costco paid its employees about 70 percent more than Sam’s Club did and spent nearly twice as much for health insurance, its higher employee retention rate and higher productivity enabled it to earn nearly twice as much per employee. His productivity and profit comparisons for Costco and Sam’s Club are shown in table 4-1.

Table 4-1 Cost and Productivity Comparisons, Costco and Sam’s Club, 2005

Sources: Adapted from data presented in Wayne F. Cascio, “The High Cost of Low Wages,” Harvard Business Review 84, no. 12 (December 2006), pp. 23–33.

* Source: Brad Stone, “How Cheap Is Craig Jelinek?” Bloomberg Businessweek, June 10–16, 2013.

** Source: Annual reports of Costco and Walmart.

Although both organizations are notoriously frugal in the ways they operate, they have distinctly different strategies when it comes to the workforce. Costco, while not embracing the union movement, has not discouraged employees from joining it—about 15 percent have. Sam’s Club, on the other hand, has avoided unionization. Although Costco has had to weather criticism from investors that the company pays its employees too much, both Costco and Sam’s Club are successful. This fact, combined with the herculean task of converting from one strategy to the other, explains why the two organizations pursued separate ways.37

Relationships to Success or Failure. Equating our low-retention and high-retention strategies to success or failure would be a mistake. Each appeals to the needs and psyches of a different group of potential employees. Some may be motivated by self-realization and some by money, regardless of the management process by which it is earned. Both groups, if matched properly to organizations that serve their primary needs, can produce good results for customers, investors, and themselves.

Foster Heroic Service Capability: Back to Mabel Yu

Our discussion of performance feedback and recognition would not be complete without a parting look at the way in which Vanguard Group recognized Mabel Yu’s remarkable work in guiding its investors away from complex investments that turned out to be unsafe. During the years that her conservative recommendations resulted in returns to investors lower than those enjoyed by Vanguard’s competitors, Yu said, “Management didn’t give me any trouble. I got only average reviews those years, but there was no big problem.”38

As a result of her determination to help Vanguard avoid problems that befell almost every other financial organization investing in derivatives, Mabel Yu became something of a media star, cited in print media and interviewed on national radio. At Vanguard, she received a typically muted recognition by an organization that doesn’t support a star system for talent and generally downplays individual performance. But she did get invited to lunch by founder John Bogle. As you might guess, the lunch took place in the “crew member galley.” Bogle picked up the bill, but Yu is said to have ordered “a salad and a drink, following the Vanguard $5 lunch coupon celebration tradition.” As she put it, “He is very frugal, so I wanted to do things his way.”39

The message of this story is clear. An organization’s values and behaviors may evolve from all parts of the organization, but their communication and preservation start at the top. The clarity with which they are communicated and the consistency with which they are practiced go a long way toward creating a workplace capable of attracting the best talent and allowing that talent to make sometimes courageous decisions. This brings us back to the Southwest Airlines agent facing a ticketed passenger in a wheelchair badly in need of a shower and some presentable clothing.

Foster Heroic Service Capability: The Airline Example

The first thing the Southwest Airlines agent said was, “I will get you on your flight [an assurance that quickly diffused the customer’s anxiety], but I would like you to cooperate with me.” She asked him to cooperate by accompanying another employee to the employees’ lounge for a quick shower and change of clothes donated by other employees. The man agreed, boarded his flight on time, and filed no complaint about discriminatory treatment.

The first words out of the mouth of this employee saved what could have been a disastrous service encounter. What happened here is testimony to the value for employees, customers, and investors of a high-retention strategy. Imagine what would have happened if the agent had been recruited haphazardly, had not been selected for a passion for the business as well as good judgment and had been given little training about what to do in hard-to-script circumstances. Worse yet, what would have happened if the agent had not been led to understand that she had the latitude to do what she felt necessary under the circumstances without checking with her supervisor. You can’t make these stories up. They happen all the time on the front lines of a service organization that hires for attitude, then trains for skills.

WILL HIGH-RETENTION STRATEGIES FOR SERVICE GAIN MORE FAVOR IN THE FUTURE?

As we look ahead, a question confronting us is whether or not we will see trends in the use of low-retention and high-retention strategies for service delivery. Our biases are evident, or we wouldn’t emphasize stories about the remarkable use of good judgment by frontline service employees who are carefully selected and trained, fully supported by management, and given the latitude (within limits) to act quickly when confronted with unusual situations.

To some observers the future for high-retention strategies appears bleak. One study of managers from a number of countries found that about one-fourth planned to leave their organizations in the coming year. In the United States, where the problem appears to be most severe, only 14 percent of companies responded that retention was not an issue. This was a proportion lower than in Asia and roughly half that of Europe.40 As economies continue to recover from the depths of the Great Recession of 2008, alternatives for employment will expand. Better information about job opportunities and better technology for accessing it are available than ever before. The supply of talent will not outpace the demand. All of these factors will make retention a greater and greater challenge.

This prospect may have prompted Walmart’s leadership to take at least modest steps toward a high-retention strategy as we finished this book. Walmart announced early in 2015 that it would raise both minimum and average wages paid to its employees. What is more significant is Walmart’s announcement that it will be providing more-regular work schedules, offering more opportunities for advancement, and focusing on recruiting and retaining “better talent so it can improve its business . . . (with) better-run stores, more satisfied customers and an increase in sales and profits.”41 Given Walmart’s size and influence in ranks of retailers, its action has called attention to at least the possibility of a high-retention strategy.

What this means is that for those organizations seeking to achieve service breakthroughs by means of high-retention personnel strategies and willing to apply the effort to do it, the opportunities for differentiation will only increase as fewer organizations find themselves up to the task.

By now it should be clear that great places to work have many moving parts. Some of those parts have to be put in place in a careful sequence. And all are dependent on the most important element of all, the quality of an organization’s leaders. Together, these moving parts are designed to make work easier and more enjoyable, to the extent possible freeing up frontline service providers to become heroes and heroines in the eyes of their customers.

Great places to work and their employees are central to delivering value to customers. When led by leaders with effective policies and practices and aided by supporting technology and systems that provide competitive edge to an organization, they can deliver world-class service. In the next two chapters, we turn to these elements of the service delivery process.