CHAPTER 6

Develop Winning Support Systems

What great service leaders know: the best uses of technology and other support systems create frontline service heroes and heroines.

What great service leaders do: they use support systems to elevate important service jobs and eliminate the worst ones.

Technology, networks, and facilities are as important to services as they are to manufacturing operations. However, for service leaders, decisions regarding the design and application of support systems comprising these elements become more complex because they often have to take into account the impact the decisions have, not just on investors but on service providers and their customers.

Too often service leaders get priorities wrong or leave out one of the important constituencies of change, most often employees. Those who have studied the problem have concluded that “it is tempting to blame poor quality on the people delivering service but frequently the real culprit is poor service system design.”1

Service leaders who design support systems that emphasize positive employee, customer, and investor experiences and value—the win-win-win philosophy of the service trifecta—can save untold amounts of operating costs while enhancing revenues. Support system design deserves the best effort from an organization’s leadership.

Technology can enhance service jobs or drain them of their content and attendant employee satisfaction. It can empower customers or leave them feeling powerless. And it can eliminate service jobs altogether, either adding to or detracting from the customer experience. By connecting employees and customers with wider networks of resources, it can foster the remote delivery of even personal services. The outcome the organization achieves depends on the degree to which technology fits within the context in which it is being applied. It also depends on those responsible for the process being aware and in agreement with an organization’s strategy and the service experience that it seeks to offer to both its customers and its employees. When implemented well, support systems can be a huge asset to service organizations; when implemented poorly, well, let’s ask Starbucks.

TECHNOLOGY AND THE STARBUCKS EXPERIENCE

The pressure on Orin Smith was undoubtedly high when he assumed the role of ceo of Starbucks (titles are not capitalized at Starbucks), the world’s best-known purveyor of coffee, in 2000.2He had had extensive experience, but he was following the company’s “father figure,” Howard Schultz, in the job. As chairman of the board, Schultz would be looking over Smith’s shoulder. The company was growing rapidly and racking up earnings that pleased Wall Street and its investors. Its share price was at an all-time high. This was a mixed blessing for Smith. It meant that expectations would be even higher for Starbucks’ growth in the future. Under Smith’s leadership, Starbucks responded by opening more stores faster, at one point five stores a day around the world.

Despite the rapidly increasing number of company stores, Starbucks’ customers experienced longer and longer waits for their lattes. This slowdown was the product of a number of incremental changes, such as the introduction of a wider range of products and types of coffee to increase sales. But in part it was because of some things that hadn’t changed, such as the quaint but outmoded slow, manually operated La Marzocco espresso machines that—while integral to the perceived artistry of the experience—slowed service. Customers loved the product but were becoming impatient with the wait time. Baristas were also experiencing increasing physical problems with the repetitive motions required to operate the machines. The Starbucks management team clearly saw that new technology was needed.

After Schultz’s retirement as ceo in 2000, his successor took the largely unnoticed step of creating an industrial engineering division. Given its new challenge, it responded by coming up with a new semiautomatic espresso machine from La Marzocco that was faster and made the job of the barista much simpler. There was only one problem with the new machine: its size. The Verismo 801, because of its capacity and internal grinding and portioning mechanism, required more space on the counter.

The technology worked just as claimed, but something was wrong. In effect, the Verismo 801s had literally and figuratively come between baristas and their customers, who were accustomed to a daily visit to Starbucks and their favorite baristas performing coffee magic. First, the new machines were faster than their predecessors, speeding up the contact between baristas and customers and allowing less time for chatting. More importantly, the machines were so large and tall that they obscured the baristas, making it all but impossible for them to carry on conversation with customers while they prepared espresso. The machines hid whatever barista magic was left in the process. All of this eroded the experience that Starbucks’ customers had come to expect. It didn’t happen overnight, but customers slowly began to find other ways to get their morning fix. It became clear that the experience was at least as important as the coffee, and Starbucks’ new system wasn’t delivering it.

In the quest for growth, Starbucks incrementally lost its distinctive ability to meet its promises to employee-partners to deliver to them interesting jobs involving satisfying customer interactions. The jobs were being dumbed down. They required less training. The equipment had taken over much of the relationship. The experience became dispiriting for both baristas and their customers. As Schultz put it, “If the barista only goes through the motions . . . then Starbucks has lost the essence of what we set out to do 40 years ago: inspire the human spirit.”3 With the new automation, something else was lost. Gone was the artistry of achieving “the perfect shot.”

By 2007 the situation had become so critical that Schultz, observing from the sidelines, could stand it no longer. He wrote a memo pointing out how and why the customer’s experience had deteriorated. Several months later, he returned to Starbucks as ceo in an effort to turn the company’s performance around. In our terms, he returned to restore the service trifecta that Starbucks had once enjoyed. We’ll return to the story later to find out what happened next.

THE SERVICE TECHNOLOGY SPECTRUM

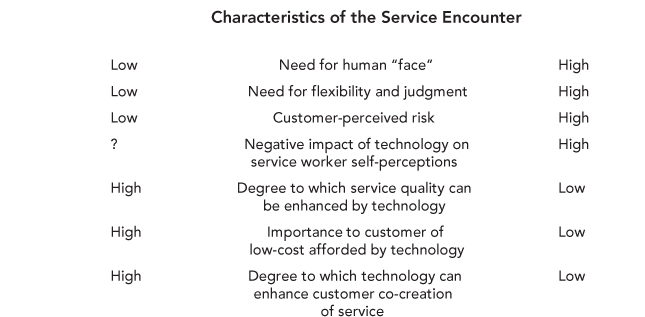

Several factors determine whether and how technology can be deployed effectively in the service encounter. These include (1) the importance of a human “face” in the service encounter, (2) the need for flexibility and judgment in the service encounter, (3) the level of anxiety and perceived risk—often mitigated by human intervention —with which a customer enters the service encounter, (4) the impact of technology on service personnel’s perceptions of the quality of their jobs, (5) the degree to which customers’ service quality perceptions can be enhanced by technology, and (6) the importance of low costs afforded by technology in customers’ perceptions of service value. A seventh and increasingly important dimension is the degree to which customers desire the opportunity to co-create services with providers, a process often facilitated by technology.

Options for employing technology range from complete disinter-mediation, in which human input is replaced, to the use of technology in subtle and creative ways that make service providers heroes in the eyes of customers. Any of these strategies can be justified as long as they enhance results and value in the eyes of employees, customers, and investors. Inappropriate uses of technology in service delivery, however, can frustrate customers, enervate and demoralize employees, and destroy value that productivity-enhancing technologies are introduced to create. Where and how to employ technology depends on where a service fits on the service technology spectrum (figure 6-1). At one extreme is the use of technology to replace service labor altogether.

Replace Service Labor: Disintermediation

As we write this, the Massachusetts Turnpike Authority is in the process of replacing toll takers with electronic readers designed to enable it to bill turnpike users. Cameras will record each transaction and provide proof that the transaction happened in order to discourage reluctant payers. The technology will reduce toll-taking costs, speed traffic on its way, and reduce automobile pollution. It eliminates boring jobs that have little or no future, that are performed in cramped quarters and often in uncomfortable conditions, and that rarely enhance the service encounter in the eyes of drivers, whose primary need is speed. Savings are so large that employees who lose their jobs can be amply compensated and given training in the skills demanded by more interesting jobs.

Figure 6-1 A Service Technology Spectrum

Invoking our service trifecta criteria for value, we see that it is a win-win-win for employees, customers, and investors. Disinter-mediation, a la the toll-taking example, is at one end of a service technology spectrum. Here, all of the criteria calling for human intervention in the service encounter register low to nonexistent on the dashboard. Although some regular commuters on the Massachusetts Turnpike may welcome a particular face in the toll booth every morning, the perceived costs to them in higher taxes to support what appear to be unnecessary jobs are not worth it. Further, there is little need for judgment in the service, it evokes little or no fear or perceived risk, the quality of the job is not improved by the technology, and customers’ perceptions of quality are raised by the technology. The scorecard dictates disintermediation by means of technology.

Disintermediation creates strange bedfellows. For example, not far from the turnpike toll takers on the service technology spectrum are college professors who lecture with no student-professor interaction. In these professors’ classes, attendance, unless required, is often low. Instead, notes from the lectures are shared among students. While the professors’ particular skills and knowledge may be irreplaceable by technology, the fruits of those skills and knowledge can be distributed without actual face-to-face communication. In fact, by means of streaming, students can experience the classroom lectures of some of the most highly renowned instructors in the world. For this reason the lecture as a form of instruction, when delivered with a less-than-stellar effort, is a threatened species in the world of higher education.

The traditional lecture eliminates the need for judgment and flexibility, generates little or no anxiety of the kind provoked by interactive teaching, and produces economics that are improved greatly with the use of technology. This would suggest that at least this one form of teaching may be ripe for the application of technology. The fact that results to date have not been uniformly positive may be testimony to the inappropriate application and execution that have characterized many of these efforts, a subject to which we will return.

Enhance Quality and Productivity

Technology that simplifies work, enhances quality, and increases the productivity of service workers is epitomized at McDonald’s by the “four-by-four system”—a technique of cooking hamburgers, 16 at a time, with the grill set at a temperature that cooks the 16th hamburger the right amount (according to management at McDonald’s) on one side at precisely the moment it is turned by the grill operator flipping the burgers in a precise sequence. It is complemented by the “two-by-two” ketchup and mustard applicators that increase productivity by a factor of four in applying condiments.

Note where this technology falls on our service technology spectrum. Here, there is a need for judgment in the cooking process that technology improves. Because the output from the four-by-four system is the same nearly every time, a customer’s anxiety and perceived risk when purchasing a McDonald’s hamburger is low. The burger is cooked the same every time. The technology improves the quality of the job and helps enhance customers’ perceptions of both the product—just what is expected every time—and service quality, because it speeds up production. Its impact on economics is muted by the fact that a grill operator is still required, although the operator can control the rate of output under the system.

Expand Human Capability

Estate planners fall somewhere near the opposite end of the service technology spectrum from toll takers. They often form close relationships with their clients, relationships that result in highly customized service encounters and outcomes. Perceived risk is high. Therefore, trust in the investment adviser and her judgment is important. It’s something that is hard to replicate with technology.

At the same time, the better the data and the information at the disposal of the adviser, the better the service experience (if not the result). Here, technology can play an important role as a support system while complementing the skills of the service provider. Technology can allow her to evaluate many more estate planning scenarios, trust vehicles, and alternative investments according to various criteria and what-if alternatives. Technology can make the estate planner look (and feel) like a heroine in the eyes of her clients. When combined with human talent and judgment, it can help produce remarkable results.

Enhance Human Talent

Think about the kinds of teaching that require an almost constant interaction between pupil and teacher. We’re not talking about the traditional lecturer, whose job was discussed above. We’re talking, for example, about tennis coaching. While the tennis coach may employ video for review purposes and an automatic volleying machine, these uses of technology merely enhance the visual, verbal, and physical interaction required to coach tennis. Actual play as well as the trained eye of the coach are irreplaceable ingredients in the service. That’s why, like estate planning, tennis coaching will be enhanced but not replaced by technology.

None of the roles for technology described above stand alone. In any application technology may, and invariably does, play several roles at once. And whether or not a technological application makes sense always has to be determined by the win-win-win criterion. Failure to include employees, customers, or investors in the calculation of benefits has led to the downfall of many applications in the past.

Overcome the Negative Effects of Technology on Human Behavior

The introduction of even the best, most reliable technology alongside human inputs can lull workers into a false sense of security on the job. Several years ago, when an Asiana Airlines captain asked his co-pilot to land the plane with a visual approach (rather than using automatic pilot) into Los Angeles, the co-pilot froze. According to the pilot, who had to take over the controls to avoid a crash, the co-pilot told him, “I don’t need to know this. We just don’t do this.”4This incident provides evidence that the introduction of automation to the cockpits of airliners has led to laxities in training that pose safety problems of their own.

Recently, efforts to create an automated subway line in Paris by the RATP (Régie Autonome des Transports Parisiens) were made more difficult by memories of the crash of a train at the Notre-Dame-de-Lorette subway station in 2000. The cause of the accident was attributed to both a malfunction of the automatic pilot and the inattentiveness of the driver.5

When many of their tasks are put on automatic, workers relax; this can be a bad combination. Because it’s never wise to assume that technology is foolproof, the design of the service requires strategic human input combined with careful selection, training, recognition, and incentives to produce a good result.

Neutralize Opposition from Organized Labor

Even with the best of intent, organizations that introduce technology into the service process often become lightning rods for opposition from organized labor unions. Here is where win-win-win thinking and the service trifecta come in handy.

The RATP had to negotiate with eight different unions in the process of obtaining support for an effort to automate one line on its Paris subway service, a move that would eliminate 630 jobs. The subsequent reduction in payroll on Paris’s busiest subway line, with about 12,000 trains a month, generating more than $15 million in monthly revenue, gave RATP’s leadership access to several options for making sure that the lives of displaced drivers could be improved, and produced a reasonable return on investment for investors without adversely affecting customer service. According to Laurent Souvigné, deputy director of the Social Relations Unit of the RATP at the time, automation presented “a social challenge which is more important than the technological one.”6

Recognize the Importance of Individual Customer Needs and Preferences

Rarely is the role of technology in services limited to only one point on the service technology spectrum. Often, different customer needs and preferences allow technology to be brought to a given service in ways that fall at all the points on the spectrum. For example, personal trainers are multiplying in numbers at precisely the time that fitness centers are being equipped with smart exercise machines—machines that provide some of the same advice as, and more precise feedback than, a personal trainer. Some people benefit from the customized coaching, personal interaction, and moral suasion that come with working with a trainer. Others, who need these things but can afford only interaction and moral suasion, work out in fitness classes. Still others simply join a fitness center and replace what a trainer has to offer with personal discipline and technology.

Ask the Right Questions

When assessing the value of a potential technological addition to any service operation, an organization will need to take a number of things into account. Before introducing any new technology to the service setting, service leaders will want to ask the following questions:

1. What is the role of service in the overall strategy of the organization? To what degree and at what points in the service delivery process can it be performed best or enhanced by technology or by human input?

2. What effect will the technology have on the service experience for the customer? Will it, for example, require more customer input to the process? If so, will this improve the service experience enough to warrant asking customers to contribute?

3. What effect will the new technology have on the nature of work? Will it relieve workers of boring tasks? Will it free up their time for more interesting work? Will it enable workers to be more productive? Will it enable less stressful work? Will it enhance or degrade self-esteem on the part of employees? Will it enable them to deliver results to customers that were previously impossible?

4. In terms of bottom-line results, will it reduce costs? Will it enable lower prices and/or higher margins and operating profits?

In short, does the technology create a win for employees, customers, and investors alike? In introducing new espresso machines, Starbucks’ management, in the case described earlier, managed to create a loss for the baristas and their customers. As a result, the inevitable result was a loss for investors as well. It flunked the test on every important dimension other than the ability of the technology to perform as advertised.

TECHNOLOGY AND EDGE

By itself, technology is not an important source of competitive edge over the long term. It is too easily replicable. Good ideas are impossible to contain and monopolize. However, when the successful application of a technology is so complex that few competitors are inclined to implement it, technology may provide an intermediate-term competitive edge.

Take, for example, the experience of world-renowned architect Frank Gehry in implementing 3D technology in the design of large, complex buildings. These buildings have to meet stringent requirements for environmental sustainability. They require extremely detailed and clear plans, which are important for the seemingly mundane but critical approval process for building permits.

Gehry’s designs rarely feature square angles and corners. Instead, they are characterized by flowing, curving elements that defy conventional architectural thinking. They constitute Gehry’s brand and competitive edge. Prior to 3D software, these elements were time-consuming to design and difficult to communicate through traditional drawings. Worse yet, they often resulted in designs that were misinterpreted and mispriced by contractors, elements that didn’t connect with one another when constructed on the job site, and conflicts between contractor and architect. These deficiencies led to job shutdowns while the problems were worked out. This is where Building Information Modeling (BIM) comes in. Developed by IBM, it incorporates techniques that solve such problems, resulting in more cost- and time-effective projects and freeing up designers to exercise their creative abilities. Or do they? Gehry’s experience suggests that they may not.

Gehry and his team have been able to use the technology effectively. But he emphasized to a reporter that

“BIM is not something that you can ‘just buy in a box.’ Instead it is a change in the way projects are organized and in the roles, responsibilities and cultures of each party involved. Adopting a new tool will get you part of the way there, but the really big advances come from using these tools to work and think differently,” he says. One of the most significant benefits of BIM is encouraging a project team to work in a more collaborative way—by setting goals and improving coordination of activities.7

When supplemented by the right organization, policies, practices, and culture, this technology can provide a sustainable competitive edge. Alone, it provides nothing of the kind.

TECHNOLOGY AND SERVICE CO-CREATION

Service co-creation can be mundane. For example, at the checkout counter of our local supermarket, many of us go to work with our grocery checker to co-create a service with the help of information technology. After we unload our selections and place them on the moving belt, items appear on a screen visible to us as they are checked, along with a running total of our purchases. Customer and checker go to work together to speed up a checkout process that is faster for both, provides more assurance to the customer (us), and yields adequate returns on the store’s investment—win-win-win.

Co-creation can also be incredibly complex, as seen in the work of architect Frank Gehry. Here, technology can help clients picture complex architectural designs with more flexibility and timeliness than ever before, involving contractors in a conversation with the architect and the builder about materials, angles, and construction challenges that could never before be addressed during a project, at least not with any speed. The results of this co-creative process are designs that could barely be conceived, let alone communicated to those responsible for building them just a few years ago. The technology makes possible for the first time a complex co-creative conversation that results in building designs never before seen in built form.

REMOTELY PERFORMED SERVICES AND THE INTERNET OF THINGS

In some service industries, even those with high levels of personal content, technology allows competitors to extend their reach. This has brought services formerly performed on a face-to-face basis into global competition with one another. This is especially true of two service industries with high information content and professional knowledge and expertise: education and medicine.

Remotely Performed Educational Services

Education delivered by means of the Internet through MOOCs (massive open online courses) represents a potentially game-changing application of technology in an industry that is to some degree in a state of denial. Even after the explosive early growth of online education, many doubters still underestimate its potential, usually citing the importance of face-to-face interaction in the educational process. Based on our personal experience, few limits apply to remote educational experiences. But quality will come at a cost. Paramount among the conditions necessary to enhance remotely performed education is the need for an occasional in-person, face-to-face meeting between an instructor and students to foster a learning relationship, which is so important to the educational process.

Periodic face-to-face contact also helps establish the norms and peer-group pressures that motivate remotely located students to complete what they’ve set out to do. Where face-to-face contact is lacking, early initiatives in which large numbers of students have enrolled with no opportunity for in-person interchange have produced high dropout rates. The courses will have to be redesigned to raise the psychological, if not economic, costs of dropping out.

Institutions of higher learning will inevitably provide official credit for MOOCs. When that happens, it will open a floodgate of users eager to obtain credit for courses taught online and by streaming techniques by some of the world’s preeminent experts on a range of topics. The next step, of course, will be the displacement of a number of classes, instructors, and even entire institutions by complete curricula offered by the Internet-based services, in an industry currently characterized by high costs, rapidly rising tuitions, too many bricks, and too much mortar.

The technology will be misused as well. In the rush to adopt it, many institutions will forego the value of combining online and classroom instruction. It will not displace all face-to-face teaching. But it will change the role that people play in the educational process at all levels, affecting a wide range of methods and jobs.

Education is no doubt one service lying in the natural path of evolution in which information technology will play an increasingly significant role vis-à-vis human inputs in the service-delivery process. Medicine is another.

Remotely Performed Medical Services

Apollo Hospitals is a hospital chain headquartered in Chennai, India. The experiences of its management illustrate both the joys and frustrations of what often seem like natural opportunities to employ technology to deliver desired results remotely.8

In 2000 the environment seemed ideal for the introduction of telemedicine at Apollo Hospitals to extend the reach of its medical expertise to rural areas of India. After all, the organization had developed a worldwide reputation for the quality of its work in several specialties, but especially in cardiac medical services. Through prudent financial management, it had been able to develop state-of-the-art facilities equipped with the latest medical technology. Its training program, initiated by founder Prathap Reddy, had produced a staff of practitioners on par with those of the cardiac care units of the world’s best hospitals, a staff current on research findings from institutions elsewhere in the world. It delivers world-class quality in the treatment of heart ailments at low cost. As a result, it has contracted with hundreds of organizations, both inside and outside India, for the long-term provision of cardiac services. Medical tourists more and more frequently come to Apollo from around the world for high-quality, low-cost treatment.

Apollo’s services were also needed in remote reaches of the state of Andhra Pradesh in which Apollo is located. Patients unable to obtain emergency advice and services, most of them quite poor, were literally dying while awaiting treatment. In response to a critical need, Apollo obtained funding to launch an experiment in telemedicine in Aaragonda, a remote village. It installed computing and communications equipment capable of facilitating the exchange of text, sounds, pictures, and videos (digital convergence) between local medical attendants and remote medical experts.

As it turned out, the technology itself—other than its initial cost and the creation of sufficient volume of use to defray the cost—was the least of the concerns of Apollo’s management. Much more formidable were the concerns of patients about the efficacy of remote diagnosis and prescription. But even this paled in comparison with the need to overcome any perceived loss of face on the part of remote practitioners who would have to admit to the need for advice, often in front of their patients. As a result, in an effort to encourage them to install and use the communications technology critical to the service, Apollo took steps to make remote practitioners feel like members of a team quite naturally delivering its services by the latest methods. It appears to be working. Today, Apollo operates more than 150 telemedicine centers in India.

Telemedicine will have application wherever medical specialties are in short supply. It will be administered from geographic centers of excellence to provide outstanding medical diagnosis and guided treatment to outlying medical service centers accessible to patients who can’t afford expensive travel and treatment. Whether it is in India or the United States, the technology will perform well. However, the problems of implementation will be the same as those encountered by Dr. Reddy in India.

The Internet of Things

At its most basic level, the Internet of Things is an emerging category that represents a broad array of products that can connect to the Internet and to each other with the objective of providing customers with smarter, more efficient, and more personalized experiences.

According to the information technology consulting firm Gartner, nearly 26 billion devices will be on the Internet of Things by 2020. All sorts of devices will be able to collect information in all sorts of physical environments. Most relevant to service providers is the ability of the Internet of Things to be responsible for taking action after the devices’ sensing. We have seen the beginnings of intelligent shopping systems that monitor customers’ shopping habits in a store by tracking their mobile devices. This data transmission and collection could instantly translate into special offers, repair services that anticipate imminent product failures, or a portfolio of service opportunities that have yet to be imagined.

The Internet of Things represents an enormous opportunity to create new and compelling service businesses out of tired product-based enterprises. As a simple example, GE’s lighting business redefined itself from a mature product organization with few growth opportunities to a large-scale service enterprise using the embedded intelligence in its lighting and electrical monitoring devices to dramatically reduce electrical consumption in homes, offices, and government buildings.

Service leaders looking to build their Internet of Things capabilities will need to recognize the importance of a carefully designed service interface that targets the needs of specific target groups. The capacity to process enormous amounts of data from these devices represents a huge challenge to those attempting to create positive customer experiences.

DESIGNING NETWORKS: MANAGE THE COST/VALUE CURVE

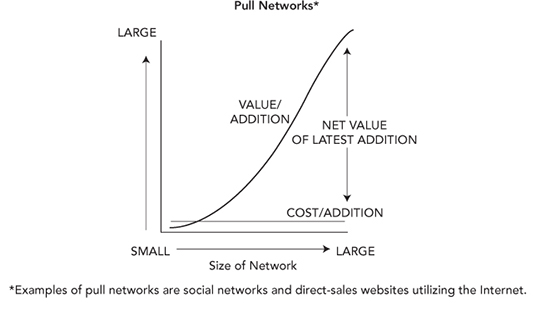

Networks represent the core of the support systems for many services, including social networks, airline route structures, and retail chain store operations. They have the property of taking on added value with the addition of each new participant, or “node.” The cost of growing a network, however, may create an economic limit on size. It’s the relationship between the value and cost of additions to a network—what we term the “cost/value curve” (figure 6-2)—that is at the heart of network management. As long as the value of incremental network size outweighs the cost, the network will be grown. Theoretically, at the point that these costs are equal, the network’s optimum size will have been reached. But enough of the theoretical world. Let’s get back to the real world.

Utilizing Pull or Push Networks

We like to think of the task of network expansion as having pull and push characteristics that influence scalability. For example, Facebook’s social network expands through the efforts of those who desire to be included. It’s a pull process driven by participant demand. Because the labor involved in expanding and maintaining the currency of the information on the network is provided by participants, the value of adding one additional member (to at least some of the existing network members) far exceeds the cost of adding that person, as shown in figure 6-2. As a result, there is no real limit on the size of the network, no point at which the cost of adding a member exceeds the general benefit, even though the benefit to each existing member may vary widely. These economics have supported the get-big-quick strategy that drives most social networking businesses.9 They have resulted in vast amounts of value being added quickly. Unfortunately, that value can be adversely affected if the network falls out of favor with participants, something we have witnessed with the rapid rise and fall of social networks that are directed to younger audiences. Contrast this with characteristics of push networks.

When John Jamotta, head of route design at Southwest Airlines, has to select the next city to be added to the airline’s network, he has to take into account not only the positive impact on the company’s revenue but also the considerable costs of establishing and operating a new station. These are costs incurred by the network’s operator in a push network, and they limit both the growth rate and the size of the network, as figure 6-2 indicates. Not only does Jamotta have to take into account costs to his company, but he also has to assess the value and costs to the airline’s Customers involved in a given design. He does so by using Southwest’s bank of data of Customer travel volumes and habits to decide how the new city will be connected to the network, especially in relation to the other cities that will be serving it directly.

Figure 6-2 Cost/Value Curves in Pull and Push Service Networks

How Much Connectivity to Provide

In Internet-based pull networks, the amount of connectivity—the degree to which various points and people in a network are connected—may be vast. Theoretically, every Facebook member is connected to every other Facebook member. But the service had to recognize that not all network members want to be connected with one another. Therefore, it had to design means (“friending”) to enable Facebook members to put limits on their personal connectivity.

The same is not necessarily true in push networks. Southwest Airlines, since its founding, has pointed out the benefits to its Customers of a point-to-point network that enables many of them to reach their destinations with a nonstop flight. As a result, it operates a network with a great deal of point-to-point connectivity. When John Jamotta adds a city to the airline’s network, he and his colleagues have to decide whether the city will be connected to just one other city through which the passenger can connect to other points on the network. Or they can do it by means of multiple connections between the new city and the existing network, something that academics term increased connectivity.

Because an airline has to populate a network with expensive terminal operations as well as even more expensive “links” (airplanes), a point-to-point network has a relatively steep cost curve unless a decision is made to limit connectivity in an effort to control costs. By contrast, the cost curve for a hub-and-spoke network is less steep, as shown in figure 6-2. It is governed by the number of hubs that are created—as well as the adverse impact on operating costs that occurs at some point in the expansion of a hub beyond a certain size.

While a hub-and-spoke network is less expensive to expand than one attempting to link all or most other points on the network to the one being added, there are offsetting costs to the passenger, who may have to negotiate several connections and plane changes to get around. This creates another kind of trade-off and a potential competitive advantage to the airline offering direct point-to-point service as opposed to service through a hub. The word potential is important here. If direct service costs more to operate than hub-and-spoke service, it either has to command higher fares or be operated at high levels of capacity usage, called the “load factor” among airlines. In the case of Southwest Airlines, its management has regularly chosen to keep fares low and bet that it will be able to attract enough passengers to achieve a high load factor on a network that is largely point-to-point. Testimony to its success in building demand to meet supply is the fact that the airline continues to be in great demand among airport authorities around the United States. They know that Southwest’s fare structure will increase traffic through their facilities by a factor of two or three.

Impact on Network “Health”

In any network, organizations must take care to ensure that new additions will not adversely affect the quality or operations of the existing network. This is especially true in a push network, such as a retail franchise chain. At McDonald’s, for example, a franchise agreement sets high standards for operation, requiring that a new franchisee work in an existing McDonald’s for a specified amount of time in addition to attending the company’s Hamburger University.

In contemplating a move to add air service to New York’s LaGuardia Airport in 2009, John Jamotta had to take into account the impact of the airport’s congestion on the rest of Southwest’s network and the poor record for on-time performance for flights into and out of the airport. Some means had to be found to shield the rest of the airline’s route network from the uncertainty introduced by serving LaGuardia. This was done by ensuring that, as often as possible, equipment was scheduled to shuttle in and out of LaGuardia from only one connecting city rather than expose other stations to the uncertainty.10

Impact on an Organization’s Culture

When it comes to company culture, organizations always run the risk of growing the network too fast. These risks are particularly high for organizations reliant on strategies based on posh networks, such as airlines. Southwest Airlines, an organization protective of its culture, has resisted requests by dozens of cities for access to its network, preferring to grow at a measured pace. In addition, in considering the LaGuardia addition, Southwest Airlines’ leadership had to ensure that it could find a supply of New Yorkers compatible with a corporate culture influenced by Southwest’s Texas roots. In this case, the decision to initiate the service was accompanied by a decision to staff the new station with a mix of New Yorkers and existing Employees from other stations.11

Effects on the Customer Experience

Regardless of the nature of network design, the most important element of design in services is the customer experience that it produces. Some Facebook customers want to be connected to as many other users as possible; some of them may have something to sell. Still others may want to be connected only with “friends” with whom they communicate frequently. They need a feature that enables them to select their friends and filter out other members of the network. The switching required to accomplish this takes place nearly instantaneously and invisibly at no cost to the user and very little cost to the network operator.

As we pointed out earlier, an equivalent process of switching in the airline travel experience is much more costly when measured in terms of the inconvenience incurred and time spent by the traveler. As a result, a hub-and-spoke airline route—one that requires passengers to transfer repeatedly from one plane to another in order to access any city on the network from any other city—will suffer in the face of competition that provides a nonstop, point-to-point alternative.

Importance of What Is Being Moved through the Network

Up to this point, we’ve assumed that our network is being designed to move messages or passengers, or somehow to serve consumers through a chain of retail stores. Instead, what if the task of the network is to move freight from one point to another? Here the concern is for total transit time and dependability. This in turn varies with the value of the cargo being moved. For example, fashion merchandise moving from the Far East to the Spain-based retailer Zara will move directly, often by air, in order to minimize transit time and potential damage. The value of such a network far exceeds the high cost. On the other hand, Mittal Steel, in transporting its output from its mills in India to its far-flung customer base, will employ the lowest-cost transport network, even if it requires making several time-consuming stops of a ship in several ports to off-load portions of a shipload of steel.

Standardization versus Customization in the Network

Walk into the Swissair terminal in Nairobi, Kenya, and you immediately think you’re back in Switzerland, given the signage, crisp uniforms, and attentive service that you experience. Regardless of the local customs and practices, that station looks and operates like any other on the Swiss airline’s network. It has to if the airline is going to project a brand that speaks to its customers with assurance that they’re going to travel safely and securely from one part of the world to another, all while experiencing Swiss hospitality.

Walk into an office of advertising agency DDB in Shanghai, however, and you might think you are entering the premises of a typical Chinese service business. Services provided, as well as policies and procedures, reflect local needs and customs, especially if the Shanghai office wants to serve local clients as well as Chinese representatives of multinational clients. In this case some core functions such as finance are standardized. But functions such as legal services and human resource management have to be decentralized and customized to fit the local laws and culture.

The issue of standardization is particularly vexing where the variance in local customer preferences is especially wide and the service organization typically has maintained a high level of standardization, often shaping customer preferences rather than catering to them. This was the case at McDonald’s, the organization that taught Americans what to expect in fast food. This was not the place to “have it your way,” as a competitor, Burger King, once advertised.

McDonald’s franchisees were the ones who convinced management that their global offerings could not be standardized completely. As a result, McDonald’s menus in Hong Kong include items such as soy green tea and dinner rice. There are core menu items like hamburgers and French fries that have to be offered under the McDonald’s franchise agreement. But McDonald’s franchisees around the world now offer menu items not found in the United States—items that reflect local preferences.12

FACILITIES DESIGN: CREATE THE SERVICESCAPE FOR THE SERVICE ENCOUNTER

The Sunday services at Willow Creek Community Church, one of the largest of the US megachurches, located in a Chicago suburb, are conducted in a large sanctuary devoid of the usual religious symbols and artifacts. Typical features of the services are soft-rock numbers performed by the church band or dramatic or humorous skits that suggest the importance of faith-based beliefs. The sermon, more like a performance, is delivered from a lectern made of a transparent material. These features are all intended to bring the speaker closer to the congregation while suggesting accessibility to the ideas being conveyed.

The services are intended for the “seekers” who may be searching for a church to join. The “seekers” may be accompanied by “believers” who also attend Wednesday evening services in the same sanctuary, but with symbols and artifacts as well as elements of a more traditional religious service. Willow Creek employs signs, symbols, and artifacts as part of a conscious strategy to create what has been termed a servicescape—a setting that both creates expectations and communicates some idea of the way in which a service will be delivered.13

Servicescapes were first cited by marketers as important ways to create an image or brand. Mary Jo Bitner then pointed out that the influence they have on employees in a service encounter is just as significant. She grouped elements of a servicescape into three categories: ambient conditions (such as temperature and sound); space and function (layout); and signs, symbols, and artifacts.14

Servicescapes serve many functions. They communicate the nature of the service, engender trust among potential customers, and facilitate the delivery of the service, whether it involves personal interaction or self-service applications.

Design Communicates the Nature of the Service

Servicescapes “speak” to a potential restaurant customer, suggesting the kind of dining experience she might have (white tablecloth or more casual, silver or plastic tableware, soft or bright lighting, oil paintings or travel photos on the wall). They communicate a great deal about the philosophy of the service, for example, whether or not the restaurant’s kitchen is visible to the diner. They include the cleanliness of the restaurant and attitudes of its employees, which convey a lot about the quality of its management. These are all signals that our diner seeks on her first visit to the restaurant. They provide what marketers have referred to as important cues about what to expect and, in fact, whether the restaurant is for her or not.15Servicescapes also influence employee perspectives on such things as the quality of the restaurant as a place to work, the amount of prestige that will be associated with the job, housekeeping standards, and the quality of the restaurant’s management. Research has suggested that these in turn influence employees’ satisfaction, motivation, and productivity on the job.16

Design Engenders Trust among Potential Customers

Trust in a service encounter is especially important when a customer perceives risk, has little information about what to expect, is a first-time user of the service, and is unable to obtain recommendations from a trusted source. It helps explain why a website such as Yelp.com, on which reviews are posted of encounters with all kinds of service providers, generates so much traffic. When customer uncertainty is high, the servicescape—in combination with such things as service-provider behaviors, customer-assurance procedures, and policies regarding such things as service guarantees—can engender needed trust.

Recently, one of us (Heskett) had to find a dentist in a community unfamiliar to him. Not knowing whom to ask, the next best thing was to get the name of the nearest dentist from Delta Dental, the insurance provider. Knowing that the treatment would probably involve that most dreaded of all procedures, a root canal, the first visit to the dentist raised some apprehension. Visual cues would be important. And the visual cues were not encouraging. The waiting room was well-worn and somewhat dreary. The equipment visible from the waiting room appeared not to be the latest. And supplies looked as though they had been stashed in an unorganized fashion in a small break room. The cues didn’t foster the trust that is so important when customers enter service encounters with high levels of perceived risk. As it turned out, the service quality was quite adequate. But the patient hasn’t returned for additional treatment.

Design Facilitates the Delivery of a Service

Servicescapes may spell the difference between the success and failure of self-serve services, where layout, signage, and instructions are critical if a customer is to successfully negotiate the servicescape and complete a transaction. Websites are servicescapes that many of us visit with increasing frequency. Their design can spell the difference between a successful transaction or a frustrated customer.

Where the service is interpersonal, any number of features may make it easier for a service worker to provide heroic service. For example, at Caesar’s Palace, several features have been built in to its high-stakes slot machines to ensure that the company’s policy of providing differentiated service to its highest-value customers is implemented. At the time that a customer swipes his Total Rewards card to begin play, the machine lights a color signaling the customer’s value to employees on the floor of the casino. Because slot machine players typically do not like to have to surrender their machines to get food or beverages, they are able to summon service to the slot machine, all paid for by means of preauthorized charges to a credit or debit card, saving the player the trouble of digging through his pockets while the machine waits. In this case, the servicescape enables Caesar’s employees to deliver differentiated levels of service to its customers, thereby reinforcing the value of Total Rewards program loyalty in their minds.

Of course, servicescapes often have to be redesigned to support the introduction of new technologies. Technology, network, and servicescape design and use can make or break a service depending on the degree to which they are consistent with one another and with the nature of the service strategy they are intended to support.

BACK TO STARBUCKS: TECHNOLOGY GONE AWRY

To pick up from where we left off, after hearing quite enough from Starbucks’s partners (employees) about how they were losing touch with customers, Schultz composed and sent a confidential e-mail to the company’s ceo and his team outlining his concerns. It was titled “The Commoditization of the Starbucks Experience”—and it was leaked by one of its recipients to the world, creating a firestorm of comment from financial analysts, investors, and partners. Financial performance of the company was still good, but Schultz was frustrated by things he saw going on in its stores. His fellow board members, with concerns about the impact of gathering storm clouds in the global economy, asked him to return as ceo at the beginning of 2008.

By the time Howard Schultz had resumed the job of ceo, a new espresso machine, the Mastrena, was in the final stages of design at Thermoplan, its Swiss manufacturer. He approved the rollout of the Mastrena but asked that it be “more artfully designed” to contribute to the Starbucks in-store customer (and barista) experience. One goal was to reduce the height of the machine on the counter to restore eye contact between barista and customer—so critical to the Starbucks service encounter. If that could be done, losses for employees, customers, and investors could be converted to wins, using our criteria for judging support systems. Schultz’s description of the result tells us a lot about the subtleties of design, his passion for the nature of the business and ideas that contribute to the coffee experience, and the complexities of fitting technology into a service strategy:

With its dusted copper and shiny metal skin and ergonomic design, the Mastrena is truly elegant. On top, a clear chalice holds fresh espresso beans waiting to be ground. Inside, every component had been engineered with Starbucks’ beans in mind. The Mastrena also, to my great joy, sits four inches lower on our counters, so baristas and customers can visually and verbally connect. By perfecting the coffee’s grind size and pour time, a barista can proudly “own” every shot.17

Schultz’s description borders on poetry. No wonder we’re still willing to pay a premium price for a Starbucks experience that incidentally includes coffee. It illustrates the subtle differences in employing technology in the delivery of experiences—the importance of visual aesthetics, communication, and employee ownership of the process for both customer and service provider—as opposed to just products and services.

Howard Schultz distanced himself just far enough from the business to become more objective about what he saw happening. What he saw was that Starbucks stores were losing their distinct “flavor.” Their servicescape was sending the wrong cues. For example, the smell of ground coffee was being displaced by the smell of cheese from the newly introduced breakfast sandwiches. Many new products were being sold. The point-of-sale equipment was outmoded.

Refocusing Starbucks required the company to drop products, restore the in-store coffee ambience, close every store for several hours so partners could be retrained, and bring back technology that reconnected baristas with their customers. As a result, nearly 20,000 of the old machines were replaced with new Mastrena machines, helping to bring back the art of the barista while restoring relationships critical to the service experience. Partner loyalty, so critical to the quality of interactions with customers, increased almost immediately. And with it, customer loyalty and profits increased as well. The company was well on its way to regaining the in-store experience that had distinguished it for so many years.

LOOKING AHEAD

Technology, network, and facility design are rapidly changing the face of services in ways that enable us to glimpse the future. The directions this work is taking make it relatively easy to predict several phenomena: anticipatory service, remotely performed services, services based on machine-to-machine (M2M) communication and the so-called Internet of Things, the deployment of robotics, and the integrated design of servicescapes around the needs of employees and customers alike.

Anticipatory Service

Organizations like GE Medical, Otis Elevator, and manufacturers of heavy-duty trucks have employed technology for many years to predict and anticipate the need for servicing their products. Sensors on an elevator provide the continuing measures that enable engineers to monitor wear and other functions in ways that make it possible for Otis’s service teams to provide maintenance on a timely basis before owners have to order it. Technology increasingly will allow a growing number of organizations to anticipate the need for service for products that to a greater and greater extent are simply computers capable of communicating their own service needs to technicians waiting to take their calls.

Remotely Performed Service

It is becoming increasingly clear that any service involving primarily the transmission of information and knowledge will, sooner or later, be performed to some degree on a remote basis. This will have a profound effect on the quality experienced by users as well as competition among service providers. Access to advice or instruction from the “best in the world” will quickly raise the standards of those being served remotely. Furthermore, it will set in motion a process by which increased competition will raise the standard even higher, putting a number of service providers at a distinct competitive disadvantage and even putting them out of work and out of business. Mediocre hospitals and educational institutions of higher learning are already feeling the pressure that will grow in other service industries as well.

Service Based on the Internet of Things and M2M Communication

In recent years so-called big-data systems have been sweeping up raw data (not information) from a variety of machines, computers, mobile devices, and other sources in ways that allow the application of advanced analytic methods that yield information about how humans behave and things work. These methods can automatically trigger actions that provide competitive edge. With increasing frequency, they involve machines and devices speaking to one another (M2M). Jahangir Mohammed, founder of Jasper Technologies, says that “when things are connected, they become a service.” His firm has produced software that “allows companies to manage and monetize those services.” For example, the software will enable stolen Nissan automobiles to send out location signals directly to law enforcement agencies. Or it will turn General Motors’ automobiles into remotely controlled Wi-Fi hotspots by linking its technology with that of AT&T to enable passengers to do whatever they now do on their computers or mobile devices, but in their automobiles.

The possibilities for services delivered through the Internet of Things are vast. In a few years, these services will become so numerous that we will take them for granted. They will enhance productivity in ways that will be credited both to service providers and manufacturers.

Deployment of Robotics

Some people have speculated about the use of robots to deliver services. It will increase, but it will be confined largely to those services not involving face-to-face contact with customers, such as warehouse order processing. The adoption of robots faces several challenges. The first, of course, is a customer’s unwillingness to interact with a robot for anything but a simple transaction, such as withdrawing money from a bank account, an application that has had nearly universal success. A more complex set of challenges involves interaction on the job, especially where robots are employed alongside humans in a team-like setting to deliver services requiring both the efficiencies of robotics and the judgment of humans. According to one analysis, “robot researchers are confronting some fascinating questions that are much less about tasks that robots can perform than what social and interpersonal capabilities they might need to persuade their human colleagues to accept them.”18

Although their use may be slow to develop, robots nevertheless will increasingly be used in services such as medical surgery and security. In such cases, they will increase productivity with an attendant loss of some service jobs.

Integrated Servicescape Design

In the future services will be designed with a greater emphasis on the customer experience rather than on marketing, operational, or financial satisfaction. In a sense, services increasingly will be designed from the inside out, starting with the customer. The concept of the servicescape will become more and more important in this process. Practitioners will consider how technology, networks, and facilities design intersect to enable service providers to deliver the desired customer experience. Integrated design will increasingly become the name of the game here.

THE ULTIMATE TEST

We can’t emphasize strongly enough that an overarching criterion in the design and implementation of any kind of support system is whether it produces a win for employees, customers, and investors. If the answer for any of these parties to a service is no, it may well be a signal that redesign is in order, no matter how large the benefit to one of the parties or the sum of the benefits to all three.

Support systems are changing at warp speed, driven primarily by changes in technology. As this occurs, wide generational differences, as usual, will be seen in the ability of managers to appreciate and envision the potential of the future. These differences explain why change is being led by young entrepreneurs rather than more senior managers in large, established organizations. The operational question for the future of the large service firm is not how it can be made more entrepreneurial. It is rather how to transport new ideas generated outside the box of the large organization into the service of the mass of customers served by the service giants. Will this be done primarily by acquisition or by a process in which the giants will be displaced by the upstarts?

Up to now, much of our discussion has assumed that services are delivered to customers. The question has been “What can we do for customers?” Going forward, the question increasingly will be “What can we do with customers?” and even “What can customers do for us?” As it turns out, they are often willing to do plenty, as we will see when we turn next to the ways in which service organizations are tapping in to the extraordinary value of customers as owners rather than just people and organizations to be targeted.