CHAPTER 6

Leading the Relational Inversion:

From Ego to Eco

The next revolution has to be a relational one: a revolution that transforms the quality of communicative action throughout social and economic systems. To make that shift, we need to bend the beam of conversational attention back to its source. Instead of just seeing others, we need to learn how to see ourselves through the eyes of others and of the whole.

One of the biggest challenges we face in moving toward an eco-system economy is to act collectively in ways that are intentional, effective, and co-creative. Over the past several years, I (Otto) have watched executives participate in a climate change simulation game at MIT, designed and led by MIT Professor John Sterman. He splits the group into small teams, with each team representing a key country group in the ongoing United Nations–sponsored negotiations over carbon emissions. The negotiators’ agreements are fed into a simulation model using actual climate data. After the model calculates the likely climate change outcomes, the negotiators go back to the table for a second round. After three or four rounds, they are presented with what is inevitably the devastating and destabilizing impact of their collective decisions on the climate worldwide.1 Then the group reflects on what they have learned.

Three Obstacles: Denial, Cynicism, and Depression

During their postnegotiation reflection session, I noted that the participants had three habitual reactions of avoidance that prevented the consequences of their actions from sinking in deeply: (1) denial, (2) cynicism, and (3) depression.

The most common strategy for reality avoidance is denial. We keep ourselves so busy with “urgent” issues that we don’t have time to focus on the one that may in fact be the most pressing. We are simply too busy rearranging the deck chairs on the Titanic. …

The second response is cynicism. Once the outcomes of an agreement become obvious, cynicism is an easy way out. A cynical person creates distance between himself and the consequences of his actions by saying, “Hey, the world is going to hell anyway; it doesn’t really matter what I do.”

But even if these first two strategies of reality avoidance are dealt with, there still is a third one waiting: depression. Depression denies us the power to collectively shift reality to a different way of operating. Depression creates a disconnect between self and Self on the level of the will—just as cynicism creates a disconnect on the level of the heart and denial creates a disconnect on the level of the mind. And into that void slips doubt, anger, and fear. Fear inhibits us from letting go of what is familiar, even when we know it doesn’t work and is holding us back.

Conversations Create the World

Learning how to deal with these three types of reality avoidance requires self-reflection and a conversation that bends the beam of attention back onto ourselves. We call this Conversation 4.0—a conversation that allows for embracing the collective shadow, as we heard in the Berlin story of the last chapter, and for unleashing our untapped reserves of creativity, as we will discuss later in this chapter.

The main problem today is that we try to solve complex problems like climate change with traditional types of conversation, which results in predictable outcomes. The collapse of the climate talks in Copenhagen in 2011 and of the MIT climate simulation game are just two of many, many examples.

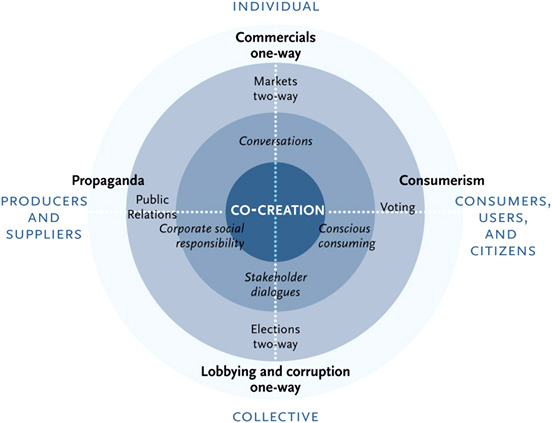

All complex modern systems—health, education, energy, sustain-ability—deal with both individual and collective entities, the latter often through government. Accordingly, figure 10, which shows how stakeholders communicate within our society’s systems, differentiates between individual and collective entities on the one hand, and suppliers and consumers on the other hand. The four levels of conversation are represented by four rings.

FIGURE 10. Four levels of stakeholder communication in economic systems.

The most common types of conversation, represented by the outermost ring, are

1. unilateral and linear;

2. low on inclusion and transparency; and

3. organized by an intention to serve the well-being of the few.

At the center are the rarest and most precious types of conversation, which offer a major acupuncture point for future change. They are

1. multilateral and cyclical;

2. high on inclusion and transparency; and

3. organized by an intention to serve the well-being of all.

LEVEL 1: UNILATERAL, ONE-WAY DOWNLOADING, AND MANIPULATING

Level 1 stakeholder communication is unilateral, one-way downloading with the intent to manipulate, rather than to serve the well-being of, the other side. Most of what we call corporate or professional communication strategy in business and election campaigns is organized this way. Market research segments citizen and consumer communities into specific target groups that are bombarded with customized messaging and communication strategies. The flood of commercials that hits consumers and citizens every day is mind-boggling. According to a survey in 1993, the average child in the United States sees twenty thousand commercials per year. The average sixty-five-year-old in the United States has seen two million commercials.

One-way communication focuses on “selling,” on making the target buy something or vote in a particular way. But the target has no opportunity to talk back. Lobbyists and special-interest groups operate the same way. Their influence often is based on privileged access and excluding other relevant parties from the conversation.

LEVEL 2: BILATERAL, TWO-WAY DISCUSSIONS, AND EXCHANGE OF VIEWPOINTS

Level 2 stakeholder communication is a bilateral, two-way discussion with the intent to provide and receive information, and includes a response or feedback mechanism. In markets, the buyer talks back with her money. In democratic elections, the voter talks back by casting her vote. Both are excellent examples of two-way communication.

LEVEL 3: MULTILATERAL STAKEHOLDER DIALOGUE: SEEING ONESELF THROUGH THE EYES OF ANOTHER

Level 3 stakeholder communication is a multilateral conversation characterized by reflection, learning, and dialogue.2 Dialogue is a conversation in which you see yourself through the eyes of another—and in the context of the whole. The examples are manifold, from roundtables and “world cafés” to interactive social media. The conversations need a form, a process, and a holding space to operate well. Some companies, like Natura, Nike, and Unilever, have internalized level 3 communication to their benefit.

For example, Eosta, an international distributor of organic fresh fruit and vegetables in the Netherlands, and also one of the first companies to be climate-neutral and use compostable packaging, wants its customers to see the “invisible” processes behind its products. A three-digit code on each of its products leads the consumer through the Eosta website to the producer. For example, the code 565 on a mango leads to Mr. Zongo in Burkina Faso, who then responds to the consumer comments online on his wall. This mechanism is an excellent example of level 3 communication because it allows consumers to see themselves in the context of the whole value chain.

Examples of multilateral stakeholder communication also include town hall meetings in New England, where citizens discuss local issues, and UN efforts such as the Framework Conventions on Climate Change. To work well, these stakeholder communication require enabling technologies and facilitation.

In the end, all of these approaches deliver the same result: They help stakeholders in a system to see themselves in the context of the other stakeholders and the larger whole. They bend the beam of attention in ways that help these distributed communities to see themselves as part of a bigger picture.

LEVEL 4: CO-CREATIVE ECO-SYSTEM INNOVATION: BLURRING THE BOUNDARY OF EGO AND ECO

Level 4 stakeholder communication is a multilateral, collectively creative eco-system conversation that helps diverse groups of players to co-sense and co-create the future by transforming awareness from ego to eco. Examples include transformative multistakeholder processes like the World Commission on Dams and the Sustainable Food Lab, which we will describe in more detail later in the book.3 The outcomes of these processes deliver not only astonishing breakthrough results, but also a shift in mindset and consciousness from ego-system awareness to ecosystem awareness—from a mindset that values one’s own well-being to a mindset that also values the well-being of one’s partners and of the whole.

LEVERAGE POINTS

Although there are some inspiring examples of level 4 innovations, it is quite clear where the main leverage points are today for shifting the system to a better way of operating:

1. We need to get rid of the toxic layer of level 1 communication (bribery, soft money, commercials, and other forms of propaganda and manipulation that keep intoxicating the communication channels of our society today).

2. And we need to develop new spheres of level 4 co-creative stakeholder relationships, in which partners in an eco-system can come together to co-sense, prototype, and co-create the future of their eco-system.

The question is how to do it. How can we build the deep capacities that will allow us to build and scale these level 4 arenas of co-creation? Here are three stories that offer some inspiration.

Girl Scouts—Arizona Cactus Pine Council (ACPC)

The CEO of the ACPC, Tamara Woodbury, sees the Girl Scouts as a part of the larger global movement that recognizes the importance of women leaders in the transformation of intractable societal issues. Since 2005, she and Presencing Institute facilitator Beth Jandernoa and her colleague Glennifer Gillespie have been experimenting with a process called Circle of Wholeness, designed to dive deeply into the qualitative practice of wholeness and well-being in the council and in the larger Arizona community. The circle, a group of eighteen, is composed of Girl Scout staff and volunteers, as well as business, nonprofit, and civic leaders, men and women, young and old (late teens to early eighties), from a range of social and ethnic backgrounds.

In October 2012, after a day spent immersing themselves in experience and research around well-being and wholeness, the group began a round of check-in, touching base with where people were in their own learning process. Beth and Glennifer felt a tension between the group’s urge to take action and the need to slow down and listen internally to what was wanting to emerge. A breakthrough moment came when John, the former CEO of an international heavy construction equipment company, shifted the action-driven momentum. He spoke slowly of his difficulties in the early phase of becoming a philanthropist. John’s quality of speech opened the group’s listening and evoked a sense of curiosity and palpable spaciousness.

Moments later, ACPC executive Carol Ackerson began to speak. Carol is known for her capacity to conceptualize and articulate complex issues so that others can easily understand them. This time, instead of taking a rational approach, she paused and said: “I know I usually speak from my head, but this time, even though it’s not comfortable, I feel it is important for me and for all of us to slow down and listen and speak from our hearts. I feel a new sensation in my body, and the meaning I make of it is, if we can be patient and keep from jumping into action, there’s a new possibility present.”

A deep silence descended on the group. As people sat quietly together, someone said, “This is amazing. What is going on?” Glennifer answered calmly: “At the beginning of a group’s gathering, silence is often awkward. As we drop into a deeper space together, we can have that rare experience as a collective that ‘silence is golden.’ Let’s keep sitting with this and let it do its work.” Beth describes her experience, in those moments, as one in which “both I and the collective were being rearranged internally—somehow transformed.” Later Carol said, “I felt as though the presence of Juliette Gordon Low, the founder of the Girl Scouts, was in the room.”

The quality of the conversation that followed this silence was alive and fresh with ideas that the group had previously never considered. They began to explore how they might define the ACPC’s “signature” conversation (the atmosphere and process) and “signature” narrative (the content of its unique principles and practices). During that meeting they identified “creating conversations that generate the experience of love” as one of the unique future competencies of ACPC.

Shifting the Conversation on Climate Change

Martin Kalungu-Banda, co-founder of Presencing Institute Africa, shares the following story:

After the Copenhagen Climate Change Conference in December 2009, there seemed to be a feeling and perception that the world had let itself down by failing to reach the kind of international agreement and commitment that would significantly and urgently begin to tackle issues of climate change. For many people and organizations, Copenhagen also exposed a disconnect between climate change discourse and development thinking and practice.

In mid-2010, the Climate and Development Knowledge Network (CDKN) began to think about how to strengthen the nexus between climate change and development. A consortium of organizations was convened to create an event that could bring new life into the climate-development nexus. This thinking culminated in the CDKN Action Lab Event, which took place in Oxford in April 2011.

Preparation for the event was led by a cross-sector group of process designers and facilitators. The intention was to create an event wherein two hundred participants from over seventy countries, covering public, private, and civil society sectors, could think and interact together in ways that could generate actionable ideas at the nexus of climate change and development. Participants’ experience and expertise were gathered using online tools. Guest speakers were identified to illuminate key aspects of the challenge. Weekly meetings were held between facilitators online over a period of four months to design and test the process for hosting and conducting the event.

The hosting environment, Oxford University, was carefully chosen for its capacity to provide the space and atmosphere required for breakthrough thinking. The best practices in human interaction and systems thinking were tapped into and brought into the design. The entire process was a mix of plenary conversations, small-group discussions, and individual moments of reflection. To maximize the creativity of the participants, various tools and techniques in creative processes, such sculpting, drawing, painting, systems games, and journaling, among others, were used.

The conference began with three days of “sensing the field,” seeking to understand and share as much as they could about the brutal facts of climate change. Next, participants went for an hour of deep reflection in the Oxford Botanic Gardens. The two questions that guided the reflection were “If I suspended all that is not essential, who would be my best future Self?” and “What is life asking me/us to do to create a different future for the world?” At the end of the reflection period, the two hundred participants returned to the plenary room. The group of two hundred somehow felt like a small group that had been seeking solutions to a common challenge together for a long time.

With unusual ease, they listened to each other’s insights arising from the hour of silence. Much of the sharing sounded like people singing from the same page of a hymnal. We had become one in seeing what was at stake, and, even if we did not say so to one another, we seemed to have glimpsed a common future through the one-hour reflection period. The experience brought a new feeling of hope after the disappointments of Copenhagen. One participant from Ghana, Winfred, said, “Copenhagen had dampened my spirit. Now I know I do not need to be a politician to make a difference. It is our turn to provide leadership to the politicians.”

Working in small groups created on the basis of interest and work/organizational focus, participants collaborated to come up with twenty-six prototypes as a way of creating the landing strips for the common future we envisioned together. Equally profound were the different collaborative relationships and networks that emerged during the four-day event.4

What is so interesting about Martin’s story is that the voices of denial, cynicism, and depression seem to have been somewhat transformed. These networks have gone on to implement some initiatives that are proving to be cutting-edge in responding to issues of climate change, as may be seen on the CDKN website, http://cdkn.org/.

One promising development that emerged from the Oxford meeting was a similar engagement in 2012 with top national leaders in Ghana, including the vice-president, cabinet ministers, members of parliament, and many others. These leaders were invited to reflect on what climate change meant to them personally. They watched a theater performance put on by local students that demonstrated the impacts of climate change, along with a documentary that showed Ghanaian citizens asking their leaders to take action. The secretary to the cabinet reflected, “All along, we have looked at climate change as an issue far from our day-to-day work. We must use the instruments of government to create a different future for our children. How could we have let this go on for so long?” To date, over four hundred additional government officials were invited to participate in a similar process, and have committed to change in their regions.5

ELIAS: Emerging Leaders Innovate across Sectors

A third story brings us to Cambridge, Massachusetts. Around 2004 we started to get frustrated. Reflecting on the bigger picture, we realized that in spite of our modest progress on this project or that one, we were not having any real impact on the three big divides. We also realized that most of our work had been focused on what went on inside individual organizations, while the biggest societal problems tended to reside in the space between institutions and individuals, among sectors, systems, and their citizens.

One day, during a conversation about this with our friends Peter Senge and Dayna Cunningham, we finally decided to do something about it. Otto would go out and talk to some of the key organizations that we had been working with over the years. Starting in 2005, Otto met with some key stakeholders in these organizations and presented the issue as follows in order to recruit them as founding partners into our idea for ELIAS:

Okay, we don’t know what the future will bring, but we all pretty much know one thing: We are entering an age in which the leaders of the future will face a series of disruptions, breakdowns, and turbulence that will be unparalleled by anything that has happened in the past. So what matters now is how we prepare the people who will end up in key leadership positions over the next decade or two, how well they are networked across systems and sectors, how well they listen, how creative they are in turning problems into opportunities. And given that no single organization can build these critical capacities alone, are you willing to experiment? Are you willing to ask some of your best high-potential leaders for four or five weeks’ time, over twelve months, to join a global group of young leaders from government, business, and the nonprofit sector in exploring the edges of both their systems and their selves?

Very much to our surprise, with only one exception, all of them said yes.

In March 2006, twenty-seven high-potential young leaders from ELIAS partner organizations, including Oxfam, WWF, Unilever, BASF, Nissan, UNICEF, InWEnt (Brazil), and the Ministry of Finance in Indonesia, began an innovation and learning journey that followed the U process of co-sensing, co-inspiring, and co-creating. While continuing in their day jobs, they joined us in developing and learning how to use a new set of innovation tools, including deep sensing journeys, stakeholder dialogues, strategy retreats, design studios, and rapid-cycle prototyping of their ideas in order to explore the future by doing.

By the end of the journey, we saw the following results:

1. profound personal change

2. deep relational change within and beyond the group

3. prototypes that showed a variety of new approaches. Some of them were really inspiring. Others simply seemed, at the time, like valuable learning experiences for everyone.

But what no one expected is that this mini-eco-system of small seedlings, or mini-prototypes, would continue to grow over the following years into a global ecology of innovation that is nothing short of amazing. Without anyone making much noise around this, these initiatives have organically replicated themselves multiple times and now involve dozens of institutions and thousands of people who continue to co-initiate new platforms of collaboration.

Here are some examples.

ELIAS Prototypes: A Global Innovation Ecology

• Participants from South Africa, the “Sunbelt team,” wanted to explore methods for bringing solar- and wind-generated power to marginalized communities using a decentralized, democratic model of energy generation to reduce CO2 emissions and for fostering economic growth and well-being in rural communities. Today the project has changed the strategic priorities of a global NGO and resulted in the formation of a mission-based company called Just Energy that operates in South Africa and helps local communities to participate in the rapidly growing market for renewable energy.6

• In Indonesia, an ELIAS fellow from the Indonesian Ministry of Trade applied the U process to establishing new government policies for sustainable sugar production. His idea was to involve all key stakeholders in the policymaking process. The results were stunning: For the first time ever, the ministry’s policy decisions did not result in violent protests or riots by farmers or others in the value chain. Now the same approach is being applied across ministries to other commodities and to standards for sustainable production.

• Also in Indonesia, a trisector U-based leadership program was launched on the model of ELIAS (now called IDEAS), involving thirty leaders from all sectors. They are working on several prototype initiatives, one of them being the Bojonegoro case, discussed later. IDEAS Indonesia now has about one hundred graduates and started its fourth program in spring 2013.

• An ELIAS fellow from GIZ (the German Ministry of Development Cooperation) developed and launched a lab for combating climate change with emerging leaders in South Africa and Indonesia.

• Using ELIAS and IDEAS as a model, in 2012 the first Chinabased IDEAS program was launched, involving senior government officials and executives from Chinese SOEs (state-owned enterprises). The second IDEAS China program, working with some of the biggest SOEs on this planet, will be launched in 2013.

• At MIT, two ELIAS fellows teamed up to create a collaborative research venture that resulted in the founding of the MIT CoLab (Community Innovators Lab). The CoLab has since emerged as a hotspot for innovation around field-based action learning for students at the MIT Department for Urban Studies and Planning, putting Theory U and related methodologies into practice.

We have also become aware of initiatives that were inspired by ELIAS, among them the Maternal Health Initiative in Namibia and the Coral Triangle Initiative (CTI), which has produced a six-country treaty linking sustainable fishing practices with revenue-sharing and economic opportunities.7 What’s so interesting about the ELIAS network is that it continues to generate an ongoing flow of ideas and initiatives.8

So what did we learn from the ELIAS project about building presencing platforms for co-creative entrepreneurial initiatives?

Five Learning Experiences

ELIAS has challenged many of our deeply held assumptions. First, we now realize that although it might well have been our most powerful and influential initiative to date, ELIAS was not born out of a clientdriven relationship. No one asked us to do it. It was born out of our deep frustration and aspiration.

Second, we learned that the framing around “problem solving” that surrounds most multistakeholder work may be limiting. The deep principle should be “Energy follows attention.” A mindset that is only about fixing a problem or closing a gap puts limits on creativity. In our case, it worked well to simply bring together young high-potential change-makers from diverse systems, sectors, and cultures, throw them into a broad set of unfiltered, raw experiences at the edges of their systems, equip them with good contemplation and reflection practices, and then let them make sense of what they saw and experienced together. Out of that, interesting new ideas were sure to emerge. With a supporting infrastructure, the result of such a process will be powerful—if the leaders have the opportunity to prototype what they believe in.

Third, we learned that individual skills and tools are usually overrated. While methods and tools have been a very important part of the ELIAS journey and the projects would not have been successful without them, it is also clear that the deep journey we were on made all the difference. Disconnected individuals became part of a co-creative network of change-makers. That journey seems to have switched on a field of inspired connections that helps people to operate from a different place, a place that is more relaxed, calm, inspired, and focused. Igniting this flame of inspired connections is the heart and essence of all education and leadership today. Everything else is secondary. In the case of ELIAS, the flame was sustained long after the program ended, and we also see it sparking outward and being reignited in many other areas. Overall it feels as if we touched a source of collectively creative power—and of karmic connections—that even today we do not fully understand.

Fourth, we learned that cross-sector platforms of innovation, leadership, and learning require a high-quality holding space. Part of that holding space is process, part of it is people, part of it is place, and part of it is purpose. But the most important ingredient is always the same: a few fully committed people who would give everything to make it work. Sometimes it’s just one or two people. But if you have four of five, you may be able to make mountains move.

Fifth, we learned to attend to the crack—an opening to a future possibility that everyone can support. All cross-sector platforms suffer the same problem: The people you need are already overcommitted in their existing institutions, which explains why in most multistakeholder platforms there is a lot of talk and little action. So the only chance of building a successful platform for cross-sector, cross-institutional innovation is to pick a topic that all of the participating individuals and their institutions value very highly.

Growing the Co-Creative Economy

ELIAS, the CDKN Action Lab Event, and the Girl Scouts—ACPC Leadership Circle have other lessons to teach as well.

First: Redraw the boundaries between cooperation and competition. Capitalism 2.0 is constructed on the logic of competition. The 3.0 economy adds government action on top of that (an example is the welfare state). Today we face challenges that are characterized by simultaneous market and government failure. These problems invite us to redraw the boundaries of competition and cooperation by introducing arenas of premarket cooperation among all sectors.

Second: The most efficient way to redraw the boundaries between competition and cooperation is to build arenas or platforms of co-creation within existing eco-systems in business and society. Eco-systems are societal systems plus their enabling social, ecological, and cultural context. Examples include education systems, health systems, food systems, energy systems, and specific business systems. The stakeholders in an eco-system share some scarce resources (the commons) that all partners have a material interest in preserving and sustaining instead of overusing.

Third: The platforms and arenas of eco-system innovation need new social technologies that help stakeholders shift their collaboration from ego-system to eco-system logic and awareness. One of these social technologies is Theory U. From a Theory U point of view, it would be key to build the following five types of innovation infrastructures:

1. Infrastructures to co-initiate. Successful multistakeholder projects are built on the same currency: the unconditional commitment from one or a few local leaders who are credible in their own communities. If the eco-system is highly fragmented, the core group that co-initiates the project must reflect the diversity of the overall eco-system.

2. Infrastructures for co-sensing. The simplest and most effective mechanism for changing our mindset from ego-system to eco-system awareness is to take people on sensing journeys to the edges of the system, where they can see it from other perspectives, particularly that of the most marginalized members. Shadowing practices and stakeholder interviews are other activities that help participants learn to see the system from the viewpoints of multiple stakeholders and from the perspective of the whole.9 Effective co-sensing infrastructures are the ones we lack most.

3. Infrastructures to co-inspire. Another increasingly powerful leverage point in the area of distributed leadership concerns the use of mindfulness and presencing practices that help decision-makers to connect to their deep sources of knowing, both individually and collectively.

4. Infrastructures for prototyping, or exploring the future by doing. Prototyping is a process. You stop worrying about what you don’t know and start acting on what you do know. A successful prototyping process requires a dedicated core group that is aligned around the same intention; a network of supportive stakeholders and users; a concrete “0.8 prototype” (one that is incomplete but elicits feedback from partners throughout the system); a firm resolve by the core group to push forward while integrating feedback from stakeholders; and review sessions that look at all the prototypes, conclude what has been learned, take out what isn’t working, and strengthen what is working.

5. Infrastructures for co-evolving. Micro- and frontline prototype initiatives are seeds that leaders can plant and support in selected parts of the system. Growing, sustaining, scaling, and evolving these initiatives in the context of the larger system require cross-functional, cross-level, and cross-institutional leadership learning and hands-on innovation initiatives. In order to provide this support, the team at the top also requires a helping infrastructure to progress on their own leadership journey from ego- to eco-system awareness.

Conclusion and Practices

Working with the U process has taught us that breaking through patterns of downloading and connecting individuals to their Self (with a capital S) is essential for an open process of co-creation. Taking a diverse group of stakeholders through a U journey bends the beam of conversation across the following stages of conversation:

Level 1: conforming, or projecting and confirming your existing judgments onto others;

Level 2: confronting, or surfacing the differences that stakeholders hold as they view the issue from very different angles;

Level 3: connecting, or holding these different views simultaneously, thereby bending the beam of attention back onto the observing self—helping a system to see itself (dialogue);

Level 4: co-creative flow, or bending the beam of attention back onto the sources of creativity and self—helping a system to connect to its emerging future Self.

TOOL: STAKEHOLDER INTERVIEWS

At the end of the earlier chapters, we offered you journaling questions as tools to explore the relevance of the chapters’ content to your own work and life. At the end of this chapter, we suggest a different tool: stakeholder interviews. The purpose of a stakeholder interview is to develop the capacity to see your work from the perspective of your most important stakeholders. It’s an example of the sensing tools that we emphasized so much in this chapter. Find the complete tool description online on www.presencing.com/tools/u-browser.

If you cannot go online, here is a short summary: Identify three to five really important stakeholders in your life and/or work. Invite each of them to a conversation in which you pose the following seven questions (modify the questions as needed for your particular situation):

1. What are you seeking to accomplish in your work, and what is my contribution to that work?

2. Can you give me an example of a time when my contribution has been helpful to you?

3. Which criteria do you use to gauge whether or not my contribution to your work has been successful?

4. Which two things, if changed in my arena of influence or responsibility within the next three to four months, would create the most value for you?

5. Which issues have made it difficult for us to work together effectively in the past?

6. What best possible future would you like to see in regard to our collaboration going forward?

7. What might be a first practical next step that will move us onto that path of desired future possibility?

CIRCLE CONVERSATION

1. Invite each person to share some key insights from the stakeholder interviews.

2. Reflect on some emerging themes.

3. Invite those who want to share a story of when they experienced of a shift in the social field, like the one in Berlin or the one that Beth Jandernoa shared in this chapter. Share a story of a time when you saw a social field shift from one state to another—what changes did you notice in the field in how people interact? What changes did you notice in yourself?