2

Structure: Systemic Disconnects

This chapter investigates the first level below the waterline of the “current reality iceberg.” What are the structural issues that lead us to reenact patterns of the past and not connect to what is emerging? What is the underlying blind spot that, if illuminated, could help us to see the hidden structures below the waterline?

The Blind Spot I

The current system produces results that nobody wants. Below the surface of what we call the landscape of social pathology lies a structure that supports existing patterns. For example, in an organization, a departmental structure defines the division of labor and people’s professional identities. In a modern society, the governmental, business, and nongovernmental sectors all develop their own ways of coordinating and self-organizing in a rapidly changing and highly intertwined world. A structure is a pattern of relationships. If we want to transform how our society responds to challenges, we need to understand the deeper structures that we continue to collectively reenact.

Eight Structural Disconnects

Here we lay out eight issue areas or visible symptoms of problems in the underlying structure. Table 1 lists each issue as follows. Column 1 describes the symptom broadly; column 2 explains the structural disconnect that gives rise to the issue in row 1; and column 3 spells out the limits that the whole system is hitting.

Addressing the root causes of these structural disconnects is like touching eight acupuncture points of economic and social transformation. If addressed as a set, these acupuncture points hold the possibility for evolving our institutions in ways that bridge the three divides. Let’s take a closer look at each one.

TABLE 1 Structural Disconnects and System Limits

1. The ecological disconnect. We consume resources at 1.5 times the regeneration capacity of Planet Earth because of a mismatch between the unlimited growth imperative and the finite resources of the planet. As a consequence, we are hitting the limits to growth, as the title of the Club of Rome study famously put the matter, which calls for a better way to preserve increasingly scarce resources.

2. The income and wealth disconnect. The top 1 percent of the world’s population own more than the bottom 90 percent, resulting in wealth concentration in one part of society and unmet basic needs in another. As a consequence, we are reaching dangerous levels of inequality, as we discuss in more detail below. This calls for a better realization of basic human rights through a rebalancing of the economic playing field.

3. The financial disconnect. Foreign exchange transactions of US$1.5 quadrillion (US$1,500 trillion) dwarf international trade of US$20 trillion (less than 1.4 percent of all foreign exchange transactions).1 This disconnect is manifest in the decoupling of the financial economy from the real economy. As a consequence, we are increasingly hitting the limits to speculation.

4. The technology disconnect. We respond to societal issues with quick technical fixes that address symptoms rather than with systemic solutions. As a consequence, we are hitting the limits to symptom-focused fixes—that is, limits to solutions that respond to problems with more technological gadgets rather than by addressing the problems’ root causes.2

5. The leadership disconnect. We collectively create results that nobody wants because decision-makers are increasingly disconnected from the people affected by their decisions. As a consequence, we are hitting the limits to leadership—that is, the limits to traditional top-down leadership that works through the mechanisms of institutional silos.

6. The consumerism disconnect. Greater material consumption does not lead to increased health and well-being. As a consequence, we are increasingly hitting the limits to consumerism, a problem that calls for reconnecting the economic process with the deep sources of happiness and well-being.

7. The governance disconnect. As a global community, we are unable to address the most pressing problems of our time because our coordination mechanisms are decoupled from the crisis of common goods. Markets are good for private goods, but are unable to fix the current tragedy of the commons. As a consequence, we are increasingly hitting the limits to competition. We need to redraw the boundary between cooperation and competition by introducing, for example, premarket areas of collaboration that enable innovation at the scale of the whole system.

8. The ownership disconnect. We face massive overuse of scarce resources, manifested in the decoupling of current ownership forms from the best societal use of scarce assets, such as our ecological commons. As a consequence, we are increasingly hitting the limits to traditional property rights. This calls for a possible third category of commons-based property rights that would better protect the interest of future generations and the planet.

As discussed in the introduction, these issue areas share common characteristics. Among them are that they (1) embody systemic structures that are designed not to learn; (2) are unaware of externalities; (3) facilitate money flowing the wrong way; and (4) allow special-interest groups to rig the system to the disadvantage of the whole.

These eight issues are symptoms of a disease that afflicts the collective social body. But what drives this pattern of organized irresponsibility? These symptoms are driven by structural disconnects that cause the system to hit a set of real-world limits. Each disconnect could be the topic of a book on its own—and in fact many books have been written about each one, such as Limits to Growth, which sparked a wave of global awareness in the 1970s. But that book, despite its significant impact, did not address other dimensions, such as financial bubbles, which are one of the key drivers of the unlimited growth imperative.

This book is an invitation to look at the entire set of disconnects as a whole system. What do we see when we contemplate them as a system? We see ourselves. The problem is us. It is we who burn resources beyond the capacity of our planet to regenerate them. It is we who participate in economic arrangements that replicate the income divide and the consumerism and burnout bubble that come with it. And it is we who use mostly traditional banks for our financial transactions in spite of our knowledge that these banks are a big part of the problem.

Each area is a part of the system that has lost its connection to the whole. Before we continue with our journey below the tip of the iceberg, let’s take a moment to look at three interesting data points that tell us something about the current health of our society.

The Economic Condition of Society Today

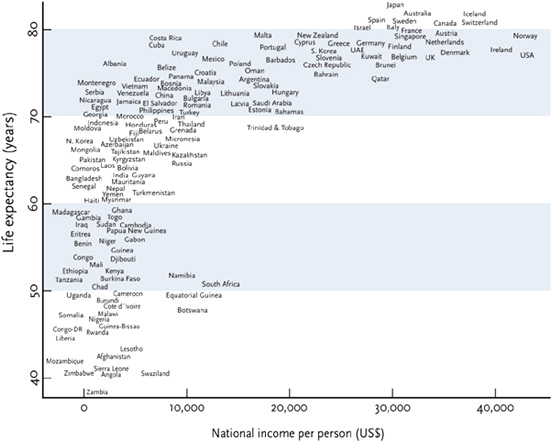

Let us first consider the link between GDP and health or well-being. The relationship between GDP and average life expectancy is often used as an indicator of the quality of health in a country. There is in fact a close link between GDP and health up to a level of US$5,000 to US$8,000 annual income per capita (see figure 6). This link weakens significantly as GDP rises above that level. In other words, an increase in material output as measured by GDP in developed countries does not translate into better health or increased life expectancy.

If a GDP increase in developed countries does little to increase the well-being of its citizens, what does improve their welfare? Surprisingly, the leverage to increase well-being seems to be connected to reducing the size of one of the above-mentioned issue bubbles: inequality.3

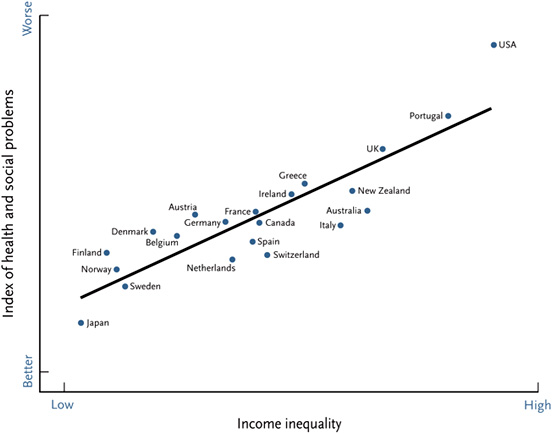

Figure 7 shows that health and social problems are more common in countries with wider income inequalities, such as the United States. On the other end of the spectrum are countries with fewer health and social problems, such as Japan, Sweden, and Norway. These countries have the lowest income inequalities among the developed countries.

These two data points raise a question: To increase the health of citizens in developed countries, would we be better off focusing on reducing the income and inequality bubble instead of focusing on improving health-care delivery?

FIGURE 6. Only in its early stages does economic growth boost life expectancy. Source: United Nations Development Program, Human Development Report (New York: Oxford University Press, 2006).

FIGURE 7. Health and social problems are closely related to inequality among rich countries. Source: Richard Wilkinson and Kate Pickett, The Spirit Level: Why Equality Is Better for Everyone (New York: Penguin, 2009), 20.

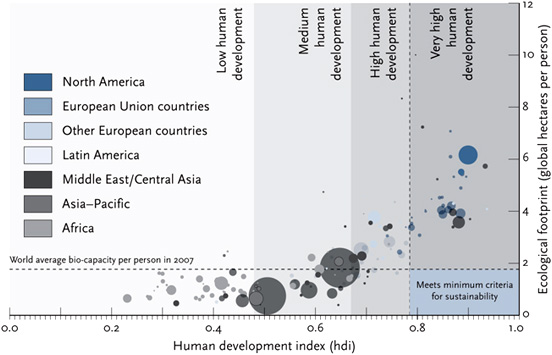

FIGURE 8. Ecological footprint versus human development index, 2008. Source: Global Footprint Network and WWF, Living Planet Report 2012 (Gland, Switzerland: WWF, 2012), 60.

Nobel Laureate Joseph Stiglitz argues in The Price of Inequality that even after the 2007–08 financial crisis, “the wealthiest 1 percent of households had 220 times the wealth of the typical American, almost double the ratio in 1962 or 1983.”4 Stiglitz emphasizes that inequality results from political failure and argues that inequality contributes not only to the social pathologies pointed out above, but also to economic instability in the form of a “vicious downward spiral.” The results are daunting: almost a quarter of all children in the United States live in poverty.5

The third data point connects this conversation to the ecological disconnect. Figure 8 depicts the sustainable development challenge to our current economy. This challenge is visualized through two thresholds. The first is the average available biocapacity per person. The second is the threshold of high human development. What would sustainable development look like? All countries would need to be in the sustainable development quadrant at the bottom right of the figure. The distance between most countries and that quadrant shows the magnitude of our challenge.

The Evolution of Capitalism as an Evolution of Consciousness

The disconnects discussed above, and the distance of most countries from the sustainable development quadrant in figure 8, are not the only daunting challenges that our societies face. According to the British historian Arnold Toynbee, societal progress happens as an interplay of challenge and response: Structural change happens when a society’s elite can no longer respond creatively to major social challenges, and old social formations are therefore replaced by new ones. Applying Toynbee’s framework of challenge and response to the socioeconomic development of our societal structures today, we briefly review capitalism’s evolution (see also table 2).6

SOCIETY 1.0: ORGANIZING AROUND HIERARCHY

Think of Europe at the end of the Thirty Years’ War in 1648, of Russia after the October Revolution in 1918, of China after the Chinese Civil War in 1949, or of Indonesia at about the time when Sukarno became its first president. Recent turmoil had created the felt need for stability—that is, for a strong visible hand, sometimes in the form of an iron fist—to provide security along with the vital allocation of scarce resources in line with much-needed public infrastructure investment. In that regard, we can view twentieth-century socialism in the Soviet Union not as (according to Marxist theory) a postcapitalist stage of economic development, but as a precapitalist (quasi-mercantilist) stage.7 The core characteristic of this stage of societal development is a strong central actor that holds the decision-making power of the whole. This could be an emperor, a czar, a dictator, or a party. Examples are manifold and include eighteenth-century European monarchs, as well as Stalin, Mao, Mubarak, and Sukarno, all of whom led coercive states whose appetite for lengthy democratic processes and discussions was, shall we say, limited. In a recent visit to the favelas of São Paulo, I (Otto) learned about the “pacification” strategy of the Brazilian police, who went into the favelas and drove out the drug lords. The young people in the favelas argued that the police presence was a good thing for two reasons. It reduced the level of random violence and allowed the community to get access to vital social services. So, in their eyes, the so-called 1.0 police structure was actually a step in the right direction.

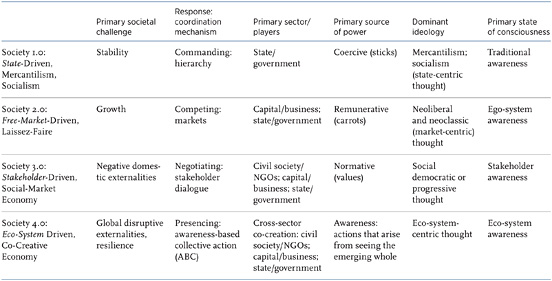

TABLE 2 The Challenge-Response Model of Economic Evolution

The positive accomplishment of a state-driven society, which we call Society 1.0, is its stability. The central power creates structure and order and calms the random violence that preceded it. The downsides of Society 1.0 are its lack of dynamism and, in most cases, its lack of nurturing individual initiative and freedom.

SOCIETY 2.0: ORGANIZING AROUND COMPETITION

Historically, the more successfully a society meets the stability challenge, the more likely it is that this stage will be followed by a shift of focus from stability to growth and greater individual initiative and freedom. This shift gives rise to markets and a dynamic entrepreneurial sector that fuels economic growth.

At this juncture, we see a whole set of institutional innovations, including the introduction of markets, property rights, and a banking system that provides access to capital. These changes facilitated the unprecedented explosion of economic growth and massive industrialization that we saw in Europe in the nineteenth century, and that we are seeing in China, India, and other emerging economies today. New York Times journalist and bestselling author Thomas Friedman links the rise of the emerging economies with the rise of a global virtual middle class that includes not only today’s actual middle class, but also the global community of Web and cellphone users who physically still live in poverty but who mentally already share an aspirational space with the current global middle class. Says Khalid Malik, the director of the UN’s Human Development Report Office: “This is a tectonic shift. The Industrial Revolution was a 10-million-person story. This is a couple-of-billion-person story.”8

Awareness during this stage of development—Society 2.0—can be described as an awakening ego-system awareness in which the self-interest of economic players acts as the animating or driving force. The bright side of this stage is the burst in entrepreneurial initiative. The dark side of this stage includes negative externalities such as unbounded commodification and its unintended side effects, including child labor, human trafficking, environmental destruction, and increased socioeconomic inequality.

The two main sources of power at this stage are state-based coercive legal and military power (sticks) and market-based remunerative power (carrots). The great positive accomplishments of the laissez-faire free-market 2.0 economy and society are rapid growth and dynamism; the downside is that it has no means of dealing with the negative externalities that it produces. Examples include poor working conditions, prices of farm products that fall below the threshold of sustainability, and highly volatile currency exchange rates and stock market bubbles that destroy precious production capital.9

SOCIETY 3.0: ORGANIZING AROUND INTEREST GROUPS

Measures to correct the problems of Society 2.0 include the introduction of labor rights, social security legislation, environmental protection, protectionist measures for farmers, and federal reserve banks that protect the national currency, all of which are designed to do the same thing: limit the unfettered market mechanism in areas where the negative externalities are dysfunctional and unacceptable. The resulting regulations, products of negotiated agreements among organized interest groups, serve to complement the existing market mechanism.

As society evolves, sectors become differentiated: first the public or governmental sector, then the private or entrepreneurial sector, and finally the civic or NGO sector. Each sector is differentiated by its own set of enabling institutions. Each sector also evolves its own forms of power (sticks, carrots, and norms) and expresses a different stage in the evolution of human consciousness, from traditional (1.0) and ego-system awareness (2.0) to an extended stakeholder awareness that facilitates partnerships with other key stakeholders (3.0). (See table 2.)

Stakeholder capitalism, or Society 3.0, as practiced in many countries, deals relatively well with the classical externalities through wealth redistribution, social security, environmental regulation, farm subsidies, and development aid. However, it fails to react in a timely manner to global challenges such as peak oil, climate change, resource scarcity, and changing demographics. Over time, response mechanisms such as farm subsidies or subsidies for ethanol-based biofuel become part of the problem rather than the solution.10 There are three essential limitations of Society 3.0: It is biased in favor of special-interest groups, it reacts mostly to negative externalities, and it has only a limited capacity for intentionally creating positive externalities. Table 2 summarizes these stages of societal evolution.

Moreover, global externalities such as climate change, environmental destruction, and extreme poverty are not being addressed effectively by domestic mechanisms, as the breakdown of international climate talks has put on display. Since the governance mechanisms of a 3.0 society give power to organized interest groups, they systematically disadvantage all groups that cannot organize as easily because they are too large (e.g., consumers, taxpayers, citizens) or because they do not yet have a voice (future generations).

Summing up, twenty-first-century problems cannot be addressed with the twentieth-century vocabulary of welfare-state problem solving. The challenge that most societies face is how to respond to externalities in a way that strengthens individual and communal entrepreneurship, self-reliance, and cross-sector creativity rather than subsidizing their absence.

SOCIETY 4.0: ORGANIZING AROUND THE EMERGING WHOLE

As we move to deal with the complexity of the twenty-first century’s landscape of challenges, we face some contradictory trends: (1) a further differentiation of societal subsystems that have their own ways of self-organizing; (2) a business subsystem that in many countries dominates and interferes with other sectors (government, civil society, media); and (3) a lack of effective platforms that engage all stakeholders in a focused effort to innovate at the scale of the whole system.

The most significant change at the beginning of this century has been the creation of platforms for cross-sector cooperation that enable change-makers to gather, become aware of, and understand the evolution of the whole system, and consequently to act from impulses that originate from that shared awareness.

Each stage discussed above is defined by a primary challenge. Society 1.0 deals with the challenge of stability. The next challenge is growth (2.0), followed by externalities (3.0). Each challenge requires society to respond by creating a new coordination mechanism. The response to the lack of stability was the creation of a centralized set of institutions around state power. Markets were the response to the growth challenge, and NGO-led stakeholder negotiations attempted to address negative externalities. Each phase led to the rise of a new societal sector: The stability challenge created a central power or government; the growth challenge created the rise of businesses; and the attempt to address the negative externalities created different NGOs that supported stakeholder groups such as labor activists, environmentalists, and human rights activists. And again, each area has its own source of power: sticks, carrots, and norms.

Each configuration also comes with a specific set of core beliefs, which we discuss in more detail in chapter 3. Society 1.0 has an ideology of state-centric core beliefs (state planning). Society 2.0 adopts a market-centered set of core beliefs (market competition). Society 3.0 operates according to a communication- or discourse-centric set of beliefs that typically integrates both markets and government (examples: twentieth-century Keynesianism or the European-style social-market economy). The last column in table 2 anticipates an emerging stage that we refer to as Society 4.0 or, to use another placeholder term, the co-creative eco-system economy, which innovates at the scale of the whole system. In this developmental framework, each system’s players operate with a different state of awareness. The 1.0 economies operate according to the primacy of traditional awareness: complying with existing mindsets and rules. The 2.0 economies awaken to the ego-system awareness that Adam Smith famously captured when he wrote: “It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own interest. We address ourselves, not to their humanity but to their self-love, and never talk to them of our own necessities but of their advantages.”11 In 3.0 economies, this self-interest is widened and mitigated by the self-interest of other stakeholders who organize collectively to bring their interests to the table through labor unions, government, NGOs, and other entities.

In the emerging 4.0 stage of our economy, the natural self-interest of the players extends to a shared awareness of the eco-system. Eco-system awareness is an internalization of the views and concerns of other stakeholders in one’s system. It requires people to develop the capacity to perceive problems from the perspective of others. The result is decisions and outcomes that benefit the whole system, not just a part of it.

A close look at today’s economies and societies reveals an awakening of eco-system awareness in numerous arenas. For example, the movements for Slow Food, conscious consuming, fair trade, LOHAS (Lifestyles of Health and Sustainability), socially responsible investing, and collaborative consumption are all extending their reach to include the concerns of others in the economic process. They can be seen as forerunners of the 4.0 state of the economy.

One Map, Many Journeys

The previous section introduced the developmental map. But the map is not the journey or the territory. The journey differs according to the historical context for each country and civilization. A quick tour through some of the main regions of our global economy illustrates various journeys and their different territories from 1.0 to 4.0. At this point, we are looking at the evolution of society from 1.0 to its current, modern form—that is, a form that is characterized by the division of labor and the differentiation of multiple subsystems.

EUROPE

At the end of the devastating Thirty Years’ War (1618–48), Europe was ready to move to Society 1.0. In 1648 the territory that today is referred to as Germany had eighteen hundred kingdoms. Over time, territorial integration increased, and the French Revolution greatly accelerated societal innovation across Europe, giving birth to Society 2.0. Starting in the early to mid-nineteenth century, negative externalities such as poverty, exploitation of low-income workers, and child labor led to a variety of societal responses and eventually to Society 3.0. Features of Society 3.0 include social security legislation, environmental laws, and consumer protection regulations. The postwar twentieth century was, from a European point of view, a significant success story for Society 3.0.

But toward the end of the century some of those achievements began to crumble when unemployment, environmental issues, and financial bubbles created problems that European governments were unable to address with a 3.0 mindset, as the euro crisis after 2008 well demonstrates.

THE UNITED STATES

Society 2.0 was born with the American Revolution. The state-centered 1.0 version of society never had a strong home base in the United States. In fact, 1.0 institutions, seen from a US perspective, might resemble more what people did not like about Europe—what made them leave the Old World for the New World. Early Society 2.0 in America was not formed to limit an oppressive US state, but to limit the oppressive European colonial states. As a consequence, even today, mistrust of government or anything that looks like a 1.0 structure runs deep in many parts of US culture. The 2.0 version of a market economy, however, was firmly grounded at home.

Throughout the twentieth century, particularly during the Great Depression of the 1930s, negative externalities in the form of mass unemployment and poverty moved the United States toward Society 3.0. Major milestones on that journey were a series of financial bubbles that sparked the creation of the Federal Reserve System in 1913 and the New Deal, which President Franklin D. Roosevelt introduced in 1933–36 (and which included white industrial workers in the North but not black farmworkers in the South). A period of relative economic stability followed, until 1980.

In the 1980s the neoliberal Reagan-Thatcher revolution began to move the country backward from 3.0 to 2.5, so to speak, by reshaping the institutional design in favor of deregulation, privatization, and tax reduction, particularly for the rich and super-rich. The deregulation of the financial system continued through several Republican and Democratic administrations. The disastrous end of the Glass-Steagall Act in 1999 happened on the watch of Democrats (under President Clinton), not Republicans, permitting commercial banks to engage in securities activities and effectively setting the stage for the near-total collapse of the global financial system less than a decade later.

President Obama’s health care reform legislation (the Affordable Care Act) completes the 3.0-related innovations that started in the early twentieth century. For the time being, as we write this in early 2013, the country remains politically paralyzed and deeply divided between 2.0 fundamentalists (on the far Right), 3.0 believers (on the traditional Left), and people who think that neither one nor the other will do the trick and that something entirely different is needed today.

AFRICA

Research suggests that the human species originated in Africa. When the nineteenth-century colonialist Europeans and other Westerners imposed a ruthless regime of exploiting the soil and the people of Africa, millions of slaves were sold to the Americas and elsewhere. Thus, the introduction of the modern state came with an iron (and malevolent) fist. The governments that were put in place by European colonial powers first and foremost served those powers’ interests.

The Arab revolution of 2011 that was ignited in Tunisia and Egypt is directed against the last strongholds of those cynical and corrupt 1.0 regimes that have continued to exist in North Africa, where Western powers have repeatedly turned a blind eye to civil rights violations in exchange for cheap oil.

Throughout the late twentieth century, the World Bank (among others) facilitated a push toward Economy 2.0 institutional innovations. The so-called Washington consensus called for market-oriented changes (deregulation, privatization, less government, and less government spending) that guided World Bank policies from 1979 to 2009. As various countries within Africa now move from 1.0 and 2.0 to 3.0 on a variety of paths, questions remain: how to help fragile states whose core societal functions and institutions have been deeply disrupted? How can a 4.0 approach that incorporates all stakeholders and all sectors strengthen the resilience and innovation capacity of the whole system?

JAPAN

When European powers colonized Asia, only two or three countries escaped that fate. Japan was one of them, Thailand and Bhutan the others. Having imported Buddhism, Confucianism, and elements of Chinese culture in the first centuries A.D., Japan developed its own version of Society 1.0 over many centuries, notably through the Tokugawa shogunate. The forced opening of Japan by Commodore Perry in 1854, followed by the Meiji Revolution in 1868, brought to Japan a second major wave of foreign culture and technology, this time from the West. It set the country on a path toward Society 2.0 and 3.0. Losing the Pacific War reimposed core elements of Society 2.0, though many cultural elements of Society 3.0 remained (e.g., keiretsus—informal sets of interrelated companies).

CHINA

With five thousand-plus years of history, China is one of the world’s oldest civilizations and home to more than 1.3 billion people. It was among the most advanced societies and economies for much of its history, but missed the Industrial Revolution in the nineteenth century and saw its decline accelerate through invasions by colonial powers from Europe. After a period of civil war in the first part of the twentieth century, China moved into the 1.0 stage under the leadership of Mao (1949), and thirty years later into stages 2.0 and 3.0 under the leadership of Deng Xiaoping and his successors.

In the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries, stages 1.0 to 3.0 tend to blend together as a single economic system (“many countries, one system”). In contrast, in China there are highly developed market economies in one part of the country and largely traditional state-led economies in other parts of the country, making China a new type of model that can best be described as “one country, many systems.” China’s success story of the past thirty years has no parallel anywhere in the world—not in the industrialization of the United Kingdom or the United States, not after the Meiji Revolution in Japan, and not in the German Wirtschaftswunder after World War II.

Yet, like everyone else, the Chinese today face massive challenges, including environmental issues, rising inequality, rising expectations from its emerging middle class, slowing growth, and increasingly disruptive and depressed global business environments. In its twelfth Five-Year Plan (2011–15), China focuses both on economic growth and on innovations to make progress on its path toward a harmonious society. While the Western media focus on China’s environmental issues and civil rights violations, Chinese industry has emerged as a leader in core technologies for renewable energy. What would a stage 4.0 Chinese economy and society look like? How can China prototype and scale an eco-system economy that has the capacity to navigate and innovate at the scale of the whole?

INDONESIA

With 17,000 islands, Indonesia is the world’s largest archipelagic state and home to 240 million people, making it the fourth most populous country and the third most populous democracy. It is also home to the world’s largest Muslim population. The nation is blessed with vast natural resources—it is the region with the second highest biodiversity on the planet. Located between China and India, Indonesia has always been a crossroads of international trade. Along with trade came the cultural influences of Hinduism and Buddhism (starting in the seventh century B.C.E.), Islam (starting in the thirteenth century), and Europe, with three and a half centuries of colonization by the Dutch (starting in the sixteenth century). The highly diverse Indonesian people united across all their divisions in a fight for independence from the Dutch and the Japanese, leading to a unified country and independent state in 1945–49.

During the era of founding president Sukarno, from 1945 to 1967, the country was run by an authoritarian, centralized government. During the following Suharto era, from 1968 to 1998, the country moved from an authoritarian 1.0 system to a 2.0 structure that blended authoritarian government with the market and foreign direct investment. After the revolution in 1998, the country moved into the 3.0 stage of its economic development, featuring its first direct presidential election (2004), the decentralization of government (2005), and the rise of civil society participation in multisector dialogue on the complex issues of economic, political, and social development. Indonesia is a founding member of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) and has been one of the fastest-growing G20 members since the economic crisis in 2008.

INDIA

India’s ancient history dates back to the Indus Valley civilization in South Asia around 2500–1900 B.C.E. Different kingdoms and sultanates stabilized the country from the Middle Ages until the eighteenth century, when European outposts began to create their own economic dominance. They brought technology and infrastructure into the country and began an alliance with the Indian elite class. The result was a shift in India’s economy. It no longer exported goods, but raw materials. India was a British colony from 1858 until the end of World War II. After its independence, when Gandhi’s notion of self-reliance was an important economic concept, India’s economic system stayed closed to external economies or economic partners. In the late 1980s, India held only 0.5 percent of the global market. This changed after a financial crisis in 1989–91. The IMF pushed for a liberalization of India’s economy and opened the door for international investors. As a result, the Indian economy exploded with a growth rate between 7 and 9 percent. The result of this development was a dual economy with a 2.0 economy dominated by large corporations that took over the role of the government and created an infrastructure in the areas where they needed it. And it left a 1.0 economy without an infrastructure outside of these corporate-regulated areas. As current growth rates start to slow down, the next steps will have to deal with the larger eco-system conditions. Current levels of corruption and the growing tensions in the overall system create new challenges for which 1.0, 2.0, and even 3.0 economies can offer no satisfying answers.

BRAZIL

With more than 200 million inhabitants, Brazil is the world’s fifth most populous country. Recognized as having the greatest biodiversity on the planet, Brazil has an economy that has grown swiftly in the twenty-first century, and it has pioneered conditional cash transfer programs that have lifted millions of people out of poverty. After three centuries of Portuguese colonial rule, Brazil declared its independence in 1822, abolished slavery in 1888, and became a presidential republic in 1889. For much of the twentieth century, until 1985, it was shaped by authoritarian military regimes that guided the country through various more or less 1.0 (state-centric) stages of economic development. With Fernando Henrique Cardoso as minister of finance (1992–94) and then as president (1994–2002), the country created a solid 2.0 economic foundation, which President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva was able to leverage while taking the economy to 3.0—that is, to a social-market economy that creates growth by putting money into the hands of the most marginalized citizens (through conditional cash transfers). Today, under President Dilma Rousseff, Brazil is facing heightened expectations, slower growth, and a new set of infrastructure challenges that will require the country to go beyond “more of the same.”

RUSSIA

In 1917, two revolutions ended the reign of the Russian czar and marked the beginning of the Russian Civil War. In 1921, at the end of this civil war, the Russian economy and living conditions were devastated. In 1922 the Russian Communist Party established the Soviet Union and a centralized economic system, a 1.0 economy. Collective agricultural production and restricted production of consumer goods were primary features of this centralization. In 1929, Stalin introduced the so-called Five-Year Plans that became the central planning tool for communist countries. The Soviet Union quickly increased its industrial production in the years prior to World War II and then again in the 1960s under Brezhnev, when it also became one of the world’s largest exporters of natural gas and oil. But the 1965 “economic reform” that aimed at introducing entrepreneurial management ideas reflected the limitation of the centralized 1.0 economy.

The war in Afghanistan, economic problems, and then the political changes that led to the revolutions in Eastern Europe ended the Soviet Union. In 1990, Mikhail Gorbachev introduced perestroika and glasnost, which marked the transition from a centralized 1.0 to a 2.0 society. After his removal from power and with guidance from Harvard advisers, this transition took full effect in the form of “shock therapy.”

The result was nothing short of catastrophic, with a rapid increase in poverty and even worse living conditions. At the same time, a small group of well-connected individuals managed to seize ownership of formerly state-owned enterprises. The poor and the less privileged suffered under a system with little regulation. These negative externalities of the 2.0 market economy were accompanied by several political and economic crises, including hyperinflation and the financial crisis of 1998. A year later, the new president, Vladimir Putin, brought back some of the centralized power structure, better balancing the dynamics of 1.0 and 2.0. Fueled by high energy prices, Russia has seen much higher and more consistent growth rates since that time.

The often harsh criticism in the Western media of Russia usually misses two points. One, it took the West an awfully long time to move from 1.0 (during the Thirty Years’ War) to 2.0 (with the Industrial Revolution). Why not give Russia at least a few years to sort these things out? And, two, in a world of ever-increasing resource scarcity, Russia is sitting on a gold mine of resources. As time goes on, the value of these resources will rise and turn Russia into a sought-after partner of both the EU and the emerging East Asian economic zone.

Globalization 1.0, 2.0, 3.0—and 4.0?

What this mini-tour demonstrates is that every country and world region takes its own developmental path. Still, the pathways of social and economic evolution across cultures do have some commonalities. We can track them as an evolution from low to high complexity, or, in terms of consciousness, from traditional and ego-system awareness to ecosystem awareness.

Yet there are also recent examples of countries that have moved backward, from 3.0 structures toward 2.0. The neoliberal Thatcher-Reagan revolution, for example, spurred many countries to scale back their domestic 3.0 accomplishments, such as social security, in order to be “competitive” in the global 2.0 competition and global capital markets.

So what is going on? One way to read the current flow of events is that waves of globalization replicate on an international level the same stages that we saw previously in individual countries:

a journey from globalization 1.0 (the United Nations system, founded in 1945 after World War II) to

2.0 (globalization of markets and capital markets, particularly after the end of the Cold War system and the collapse of the Berlin Wall in 1989), to

3.0 (globalization of civil society, particularly after the World Trade Organization–related “battle of Seattle” in 1999), and perhaps to

4.0, an emerging future state of global cross-sector co-creation for protecting the commons

Conclusion and Practices

This chapter investigated the first dimension of our blind spot: structural disconnects. As a set, these systemic disconnects could spur the next wave of institutional renewal, just as a hundred years ago the crisis of the 2.0 laissez-faire market economy catalyzed a whole new wave of institutional innovations that today we associate with the 3.0 social-market economy.

JOURNALING QUESTIONS

Take a journal (or blank piece of paper) and reflect on how the systemic disconnects show up in your world by writing your responses to the questions below.

1. Where does your food come from?

2. What roles does material consumption play in your life?

3. What makes you happy?

4. What is your relationship to money?

5. Given the four stages of economic development discussed in this chapter, how do you see the past, present, and future of your own community and country?

CIRCLE CONVERSATION

Form a circle of five to seven individuals and discuss the organizational or professional context that each person brings to the circle. Ask the following questions (or some variation):

1. Introduce your own organization by relating one or two formative experiences that shaped its culture as it is today.

2. Where does your organization experience a world that is ending/dying, and where does it experience a world that is beginning/wanting to be born?

3. What do you consider to be the root causes of the problems that you face in your institutional and professional work today?

4. What do you personally feel is going to happen in and to your organization over the next ten to twenty years?

5. What would you like to do right now in order to make a difference for your organization going forward?