7

Leading the Institutional Inversion:

Toward Eco-System Economies

The next social revolution has to be an institutional one. A revolution that helps us to bend the beam of institutional attention all the way back to source—that is, to a place where the institutional system can see and renew itself.

Shifting the Locus of Leadership

What do you do when you are part of a system whose vital components operate in separate silos? Answer: You connect them. You shift the locus of leadership from the center to the periphery—that is, from one place to many places. You connect these places in ways that facilitate sense-making in more distributed, direct, and dialogic ways.

We witness this process of shifting the locus of leadership from one place in the center to many places on the periphery in numerous institutions today. The process is driven by globalization, the rise of the World Wide Web, and the blend of new information and communication technologies that allow for distributed and decentralized ways of organizing. We witnessed a first wave of this process when global companies and organizations started to decentralize their decision-making processes according to functions, divisions, and geography.

Today we see a second wave further shifting the locus of leadership. Decision-making is being pushed even further out, beyond the boundaries of the organization. This process is referred to by different names: extended enterprise, innovation eco-system, crowdsourcing, swarm intelligence. What is happening in organizations today is what has happened to nation-states in a globalized world before: Both became too small for the big problems and too big for the small problems.

The result is an inversion of the old model. The pyramid is flipped upside-down so that the cultivation of co-creative relationships among stakeholders is at the heart of the new eco-system model of organizing.

Institutional Inversion

Before we begin discussing different examples of institutional inversion, let us briefly review the four main logics of institutional power and organizing.

We will track the journey from 1.0 to 4.0 through the concept of inversion, which is a translation of the German Umstülpung (inverting and upending). Otto came across the concept of Umstülpung when studying the work of the German avant-garde artist Joseph Beuys in Germany. The simplest example of inversion is this: Hold a sock in one hand and with the other reach deep inside it, pulling the toe back until you have turned the whole thing inside out. The completion of that movement is inversion, or Umstülpung.

The same principle applies to transforming the field structure of an institution. Here it means inverting the geometry of power. The following four figures present a graphical depiction of that process: The source of power shifts from the top-center of the pyramid (1.0) to closer to the base (2.0), then to the periphery (3.0) and to the surrounding sphere of a system (4.0). The resulting structural journey of transformation is marked by a complete inversion.

In 1.0 structures, power is located at the top of the pyramid. The organizational structure is centralized and top down. Coordination works through hierarchy and centralized regulation or planning. The 1.0 structures work well as long as the core group at the top is really good and the organization is relatively small. Once organizations or companies begin to grow, they need to decentralize in order to move decision-making closer to markets or citizens. The resulting 2.0 structures are defined by both hierarchy and competition.

In a 2.0 structure, decentralization enables the source of power to move closer to the real work in the periphery. Coordination works through markets and competition. The focus shifts from inputs to output. The result is a functionally or divisionally differentiated structure in which decisions are made closer to markets and consumers or to communities and citizens (figure 12). The good thing about 2.0 structures is the entrepreneurial independence of all of its divisions or units. The bad thing is that no one is managing the space between the units.

FIGURE 11. Structure 1.0: pyramid. Power is centralized and resides at the top. Solid lines here indicate traditional vertical leadership structures.

FIGURE 12. Structure 2.0: decentralized. The source of power moves closer to the base.

FIGURE 13. Structure 3.0: networked. Sources of power turn relational. Dotted lines here and in the following figures indicate networked and relational leadership, rather than hierarchical structures.

Which brings us to 3.0 structures, in which the source of power moves even farther from the top and originates beyond the traditional boundaries of the organization. The result is a flattening of structures and a networked type of organizing. Coordination works through negotiation and dialogue among stakeholders and organized interest groups. Power emerges from the relationships between players across boundaries (figure 13).

The good thing about 3.0 structures is their networked connections. The bad thing is the increase in vested interests. Special-interest groups use their networked connections to benefit their ego-interests while compromising the well-being of the whole. Examples include Wall Street (making taxpayers pay for its own risk-taking), Monsanto (displacing farmers in India from their cultural property rights), big energy companies (funding pseudo-science around climate change that is designed to confuse the public), the health industry (keeping health-care costs outrageously high), labor unions (often paying little attention to the well-being of unemployed nonmembers), and environmental organizations (often paying little attention to the well-being of communities in protected areas).1

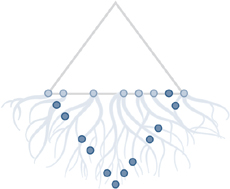

In 4.0 structures, the source of power moves to the surrounding sphere of co-creative relationships among individuals and institutions in the entire eco-system. Coordination works through shared attention to the emerging whole. In 4.0, power emerges from the presence of that whole (we-in-me) rather than the mere ego-presence of its members (I-in-me) in a given eco-system. Figure 14 shows that the flattening of the hierarchy from 1.0 to 3.0 continues below the baseline. The U-shaped territory below the baseline of the flipped pyramid represents the transformed relational space through the opening of the mind, heart, and will.

The journey from 1.0 to 4.0 is an inversion story in two respects. First, it is an inversion of the source of power from the top and center (1.0) to the base/periphery (2.0) to beyond the organizational boundaries (3.0) to the surrounding eco-system (4.0). This journey is a profound opening process of a closed pyramid (1.0) until it is completely upended and inverted (4.0).

And, second, it is an inversion that concerns the reintegration of mind and matter. In 1.0, the mind-matter split is the defining feature of the system: Leadership power originates at the top, and there is maximum distance between the top and the base of the pyramid—that is, between mind (governing, leading) and matter (frontline work). The rest of the journey reduces and transforms the distance between the top and the base of the system (the pyramid) as follows. In 2.0 structures, the vertical split is somewhat reduced through decentralizing and divisionalizing. In 3.0 structures, the vertical split is further narrowed through horizontal networked organizing at the base of the system. Networked organizing is effective at reducing the vertical distance, but is less effective at transforming habitual mindsets. The final shift, to 4.0, is a move from the base of what used to be a pyramid to a “negative space” below the former pyramid’s base—that is, to a space that allows the system to see itself in order to facilitate the shift from ego-system to eco-system awareness. Any system or community that wants to become aware of itself has to cultivate that negative space below the former base; that is, it has to cultivate the soil of the social field, the root system of the emerging new 4.0 types of organizing.

FIGURE 14. Structure 4.0: inverted pyramid. Transforming relationships from ego (I-in-me) to eco (we-in-me).

Institutional inversion can thus be described as a profound opening process that shifts the source of power from the top/center to the surrounding sphere. It can also be told as a story of overcoming the vertical mind-matter split between leadership and frontline work in a system by inverting the pyramidal structure into a U-shaped holding space that cultivates the root processes of the social field: attending, conversing, organizing, and integrating.

Leading the 4.0 Revolution across Sectors

In spite of the importance of personal and relational change, we all know that none of the change initiatives discussed in earlier chapters will make a dent in the global challenges that we face unless we succeed in transforming the key institutions that constitute our society’s systems.

The way we do this is by helping them to advance to 4.0. This requires a process of institutional inversion that replaces and supplements the old mechanisms of hierarchy and competition. The cultivation of dialogic and co-creative relationships will allow the stakeholders in each eco-system to innovate at the scale of the whole.

This chapter outlines a developmental roadmap for the institutional transformation that our generation is called to bring about. We can do it proactively, or we can leave it to our children after a long series of painful external disruptions and shocks. It’s a transformation that has been in the making for many years. The journey to 4.0 is the next stage of a process that has been continuing over several centuries, and which differs in form based on place, sector, and culture. The 4.0 revolution will look different in China, South America, and Africa than it looks in the West. It will also differ somewhat across systems of health, education, energy, and agriculture. Yet in essence our experience has been that all sectors and systems deal fundamentally with the same challenge: to develop the capacity to act from the whole.

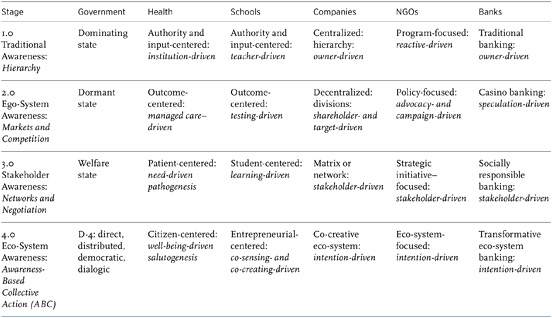

TABLE 9 Sectors of the Current Institutional Transformation

Table 9 provides an overview of this chapter: It shows how all of society’s systems have been walking on parallel paths from 1.0 to the emerging possibility of 4.0. The rest of the chapter focuses on how to move each system from ego- to eco-system awareness—that is, from organizing around special interests to organizing around common intention. The walls of the silos that have contained these systems for so long will gradually but inevitably open up as we progress on our journey toward 4.0.

GOVERNMENT AND DEMOCRACY 4.0:

DIRECT, DISTRIBUTED, DIGITAL, AND DIALOGIC

The journey to Government 4.0 is an institutional transformation from

1.0: a centralized ruler-centric system (l’état c’est moi—“the State, it’s me”); to

2.0: an abstract, differentiated machine bureaucracy (à la Max Weber); to

3.0: a networked government that pays more attention to citizens; to

4.0: a distributed, direct, dialogic system that operates by connecting to and empowering its citizens to co-shape the whole.

This journey to Government 4.0 is highly intertwined with the journey to Democracy 4.0, which moves from

1.0: one-party democracy (centralized); to

2.0: multiparty indirect (parliamentary) democracy; to

3.0: participatory indirect (parliamentary) democracy; to

4.0: participatory direct, distributed, digital, and dialogic (4-D) democracy.

The transformation to Democracy 4.0 entails shifting the source of power from the habitual actions of the center to the real needs and aspirations of the communities on the periphery—from a top-down leadership to a shared process of co-sensing and co-shaping the new.

Here are two examples that offer some glimpses of that emerging future.

Bojonegoro, East Java, Indonesia:

Shifting the Field of Democracy to 4.0

The IDEAS Indonesia program that Otto chairs at MIT is a nine-month innovation journey based on systems thinking and presencing that guides diverse groups of high-potential leaders from government, business, and NGOs through a deep immersion journey to the edges of society and self. In the second half of that program, participants develop prototype initiatives to explore the future by doing. One prototype generated in one of the recent programs addressed the issue of government corruption.

Led by Bupati Suyoto, the regent of Bojonegoro, the prototype’s goal was to reduce corruption and improve the quality of government services in the district. In a move from Government 1.0 to 2.0, in 2005 Indonesia shifted from centralized governmental decision-making to a more decentralized model that empowered the four hundred regencies in the country and their directly elected Bupatis (regents).

Bojonegoro, one of these regencies in East Java, had long been known for high levels of corruption and low service quality. But in 2011 and 2012, Bojonegoro emerged as one of the ten best regencies nationwide according to various quality assessments, and received multiple prestigious awards for low levels of corruption and high levels of service quality. What happened?

Bupati Suyoto, a 2010 graduate of the MIT IDEAS Indonesia program, came into power without any support from established interest groups. With no money and no budget for his election campaign, at first no one gave him a chance. But he did the only thing he could: He went to the villages and listened to the citizens. In a surprise victory, he removed the incumbent Bupati from his post. In 2012, he was reelected by an even wider margin, even though other candidates were backed by powerful industrial interests (the region has one of the biggest oil reservoirs in the country) and ran very expensive advertising campaigns against him. So again, what happened? How is it possible that a single person with no big-business support could run and win against powerful vested interests like the oil industry?

On his first day in office, Bupati Suyoto called for a general assembly of all government employees in his regency. Many of the senior people expected to lose their jobs because they had actively worked against him during the campaign. In his address to them, Suyoto delivered two main messages. First: Everyone would keep their jobs. He said that he didn’t want to look backward but to look forward, building a future that would be different from the past. The other message consisted of three things he didn’t want them to do: (1) Don’t take any money; (2) don’t complain about your job; and (3) don’t say, “This is not my job” or “This is not my responsibility.”

When he delivered these messages, people were surprised. They listened politely, but hardly anyone believed that he really meant what he said. According to some of the participants, probably 80 percent of them remained skeptical. After all, most public servants and politicians had had to borrow money to “buy” their current positions and hence needed bribes to repay these loans.

So how did the Bupati manage to shift the mindsets of the skeptics who surrounded him in office in spite of all these economic forces working against him? In the beginning, he made three primary moves.

First, he continued to communicate the three don’ts and embodied these principles in his own everyday behavior. For example, in his official residence, he opted to use the small guest quarters for himself and his family while offering his official guests (and sometimes his driver) the larger space. With this unusual move, he demonstrated that the State House didn’t belong to him personally; he was just there as a guest, like everyone else before him and after him.

Second, he developed a series of intense offsite leadership retreats with his core team. These retreats facilitated the letting-go of old mindsets and tuning in to new inspirations, intentions, and identities.

Third, he started to close the feedback loop between people and their government officials. How? By activating four simple mechanisms:

1. Text messaging: He gave his cell phone number to citizens and told them that they could text him at any time. Since then he has received hundreds of text messages every day. He responds to many of them personally. Many others he forwards to his directors and department heads. Everyone in his administration is expected to respond to a message from a citizen within a day or two.

2. Open door: Anyone can walk into his office at any time.

3. Town hall: Every Friday afternoon he conducts a town hall community dialogue meeting to which all citizens are invited and which all his top civil servants are required to attend. I (Otto) attended one of these meetings. First a farmer raised his issue: He had no access to fertilizers. When he sat down, the microphone went to the head of the Department of Agriculture to explain the problem and say what could be done to fix it. The department head was a bit defensive. But he also knew that next week he would be back there facing the same people and the Bupati. So he had every incentive to fix the problem within a week’s time. Next came a woman in her twenties wearing a hijab, the Muslim head scarf. She said she was an educator and needed books to support her teaching in the villages. The classes that she wanted to teach included sex education for girls, and there were no instructional materials available. She completed her request without any sign of fear or hesitation (I had to remind myself that I was watching a town hall meeting in the biggest Muslim country on earth). The Bupati responded by telling her how to find the resources she needed. He said that one of the big US oil companies had come to his office earlier that day and asked what they could do to help the community. The Bupati told the teacher to submit to him a summary of the program and also pose her request directly to the oil company. There is no doubt that she will get what she needed. Nevertheless, if she stumbles into unexpected delays from the oil company or even his own staff, she should come back to him. Everyone in the community was listening to the exchange between the young woman from the village and the Bupati—and that shared listening turned her initiative into a legitimate community project.

4. Village visits: Fourth, every single day the Bupati takes his key officials to villages where they conduct a similar dialogue on a local level.

What do these four mechanisms add up to? Listening. Listening by government officials to the everyday experiences of their citizens. Listening by different citizen groups to one another. And listening by the community to itself (dialogue).

When I saw these different types of listening closing all the feedback loops, I thought, “Boy, that’s exactly what’s missing in our democratic institutions in the West and other parts of the world today.” In the West, elected officials spend all their time listening to the lobbyists and organized interest groups who finance their election campaigns. For example, in the United States, members of Congress spend about 50 percent of their time fundraising for their next election campaign. The system works by turning lawmakers away from listening to real citizen needs. In contrast, the Bojonegoro story worked by interrupting that toxic cycle (the “three don’ts”) and then establishing four direct feedback loops. The promulgation of Law 23/2011, passed in 2011, evidenced that the four direct feedback loops can be written in stone and applied not only in Bojonegoro but also have greater implications at the national level of greater Indonesia. This is another great example of how leaders can efficiently listen to constituents. It also proves that political parties are actually manageable when the leader is independent, sound, and solid.

In a nutshell, what we saw in Bojonegoro was a profound shift in the field of government and democracy from primarily 1.0 to what may have been 3.0, with the first elements of 4.0. That shift deepened democratic forms by making government more direct, distributed, digital, and dialogic. I felt that community’s presence when I was asked, at the end of the gathering in the town hall, to address the group. It was an intimate and grounding experience. I felt the power of community for a moment or two—a power that in most places today is shockingly underused.

Without significant strengthening of 4-D citizen connections, Western democracy could soon find itself in the same situation that an American colonel faced in 1975 when he debated a North Vietnamese colonel. “You know you never defeated us on the battlefield,” said the American colonel. The North Vietnamese colonel pondered this remark a moment. “That may be so,” he replied, “but it is also irrelevant.”2

To stay relevant to the challenges of our time, we have to advance our institutions of democracy and government to 4.0. Examples like Bojonegoro can give us some seeds of inspiration for that. Another seed of inspiration for Government 4.0 comes from Brazil.

Brazil: Transforming the Secretariat of the National Heritage

Alexandra Reschke served as Brazilian Secretary General for National Heritage (SPU) during President Lula’s term. Upon taking office, she saw that the organization was becoming obsolete, a result of disregard on the part of previous administrations. Reschke also noticed that the way people communicated within the organization was harming relationships. She saw this as a leverage point for sparking change within the organization. This strategy proved so successful that eight years later, the changes Reschke set in motion are still visible and felt. What did she do, and how?

As a woman in a very powerful position, she purposefully chose what she called “a feminine leadership style” and recommended that decision-making happen through circles of conversation. Thus began a new era at SPU.

The idea was to shift away from people not saying what they were feeling and thinking and toward a way of conversing where the conversation itself would become the field for collaboration and generative action. She put a process into place to change existing communication habits, adding moments of stillness and retreat before the circles. She immediately started preparing for the first National Strategic Management of SPU, which occurred in early 2004, bringing together all the leaders in Brasília and several of SPU’s partners for the first time in its 150 years of existence.

Over the years, SPU managed to change the very structure of the organization, from an authoritarian, pyramid model to circles of conversation. SPU went from being “obsolete” to being recognized as an outstanding public agency by 2007. It brought together different sectors of society to create an innovative and legal participatory way to ensure regularization of land for thousands of riverside communities in the Amazon.3

Reschke summarizes her journey with three lessons: (1) Dare to be different; (2) believe in people; and (3) invest in cooperation. “We moved together [as people]; as a result the institution came along.”4 For her, the learning came from the willingness of people at SPU to exercise the values of authentic conversation and empathic listening as a new way of co-shaping their collective future.

Another interesting example is the participatory budgeting model that the city of Porto Alegre, Brazil, pioneered starting in 1989. It allows its citizens to discuss, identify, and prioritize public spending projects. It has been an inspiration to many and has been replicated in more than 140 municipalities in Brazil. According to a study by the World Bank, it has led to better matching of social services with community needs. However, it has been also criticized for not sufficiently involving the most marginalized groups (people living in poverty as well as young people) and for the susceptibility of the process to hijacking by existing vested interests.5

The two regions with the most efficient governments and public services in the world are the Confucian cultural sphere in East and Southeast Asia (Singapore, Korea, Japan, China, Taiwan, and Vietnam), and Northern Europe. The Nordic countries (Denmark, Sweden, Finland, and to some degree Norway) and Singapore are at the top of the rankings for government efficiency, education, health, competiveness, and well-being. The Nordic countries faced a perfect storm in the 1990s when all their eastern markets disappeared with the collapse of the Soviet Union, and their 3.0 welfare state model faced a severe financial crisis. Nonetheless, since then, these countries and their public sectors have reemerged with a leaner, better, and more transparent model of government that focuses on empowering citizens to be entrepreneurial and inventive (for more detail, see the story about the Danish health system later in this chapter).6

HEALTH 4.0

The institutional transformation of the health-care system follows roughly the same journey from 1.0 to 4.0 that we have described in other areas. It is a journey from

1.0: input and authority-centered institutional care; to

2.0: outcome-centered managed care; to

3.0: patient-centered integrative care; to

4.0: citizen-centered holistic-integral care.

Here are two examples that shed some light on transforming a health-care system in light of the above framework.

Namibia

Our work on the health-care system in Namibia started as a partnership among the Synergos Institute, McKinsey and Company, and the Presencing Institute. In the early stages of the process, in the fall of 2010, Otto conducted a three-day workshop with the cabinet of Namibia. On the first day, the prime minister explained the core issue they were confronted with, as he saw it: “We need to reconnect our political process to the real needs of the communities. Right now our political process is largely disconnected from the real needs in the villages.”7

One of the ministers added: “Here is what our situation is like. You must understand that we have all these planning routines. We have our vision 2030. We have our five-year plan. We have our strategic plan. And we have our annual budget plans. To develop all of these plans takes a lot of time. The problem is that these plans do not talk to each other and they all do not connect to what is really going on.” All of the government leaders in the room agreed that this was a major issue they were dealing with: the disconnect between their government routines and services on the one hand and the actual needs of the village communities on the other hand.

The second disconnect they described involved the top of the pyramid. “We cannot really talk to our top civil servants,” one minister explained to me; “they do not really take us seriously. They feel they got into their job through professional qualifications, but that we, the ministers, are just political appointees. You know, just because we have political connections, not because we are competent.” Other ministers in the room nodded in agreement.

Then another minister explained a third disconnect, the pervasive silo issue that fragments the work of government agencies in many places. “The silo issue starts right here, between us,” she said and looked into the faces of her colleagues, “because we do not really talk straight with each other. It starts with us and then the same behavior gets replicated throughout our ministries.” The silo issue impedes communication between as well as inside ministries.

Our work with the Ministry of Health and Social Services confirmed the existence of these divides. We started with a joint assessment of the situation that identified weak leadership, work processes separated into silos, dysfunctional structures, no strategic planning, no proper data collection, and no clear targets, and we found that the ministry was off track to meet the UN’s Millennium Development Goals (MDGs).

After three years of collaboration, several of these problems have been successfully addressed, though many will require further work. Throughout this process, however, something very important has changed. Namibia’s leaders have begun to recognize their own role in perpetuating the problems and are taking initiative and responsibility in working on innovative solutions.

Here are a few lessons we identified from their journey of transforming the system beyond 1.0:

Co-initiation. The first phase established common ground and a shared intention among the Namibian Ministry of Health’s key players. The international partners wanted to develop cross-sector platforms of innovation and leadership. The ministry leaders, however, were more interested in getting their civil servants to work as a team. We (the international and Namibian facilitation team) therefore abandoned our original plan and started by attending to the stated needs of our partners on the ground. We realized that if you want to change others, you first need to be open to change yourself.

Co-sensing. A successful sensing journey breaks down outdated and artificial boundaries. In Namibia, we had to open health leaders’ eyes to the system as seen through the eyes of patients, nurses, and remote communities. This type of sensing journey is conducted in small groups of five to seven persons (so everyone can fit into one car or van) over multiple days.

Co-inspiring. The most important change in any transformation journey is the change of heart. That change requires deep reflection and contemplation practices along with a supportive infrastructure, including workshops, coaching, and peer coaching. These activities address both individual needs and the team or organizational culture: reconnecting to the deeper purpose, developing team spirit, prioritizing, and encouraging personal responsibility.

Co-creating. All deep cultural changes and institutional innovations require learning by doing. The prototyping stage in the Namibian health project generated the idea for Regional Delivery Units (RDUs). A small cross-sector group of leaders, including nurses, doctors, and the regional director, hold weekly meetings as a way of learning by doing. Their objective is to improve maternal health. Each discussion begins with a review of the week’s data and events. These meetings allow professionals of different ranks to communicate, question one another, and exchange views in a supportive and nonjudgmental environment. At one of the RDU team meetings I (Otto) attended, they discussed a situation of concern to the nurses. At one point in the discussion, a junior nurse, a young woman, turned to the most senior leader at the table (the director of the entire region), who had not participated in the discussion before. She said: “I gather from your body language that you do not agree with what is being said here.” And then it was the director’s turn to explain his reading of the situation. When I heard that junior nurse draw out the most senior person in the group, I knew that something was working—they had established a constructive communication and learning culture.

Today (in 2013) these RDU team processes are being rolled out throughout Namibia’s thirteen regions. This work is being performed by and is owned by Namibians, without any of the international partners. The RDU process helps leaders in the regions to focus on accountability for improved outcomes. The teams then drive policy implementation, coordinate service delivery, manage progress on goals, and solve problems to ensure the effectiveness of health interventions. Discovering what makes these groups effective is an ongoing process of learning by doing.

Co-evolving. “I used to think that the Permanent Secretary in Windhoek had to take final responsibility for health. But now I understand that I am the permanent secretary of my region and I have to take responsibility,” says Bertha Katjivena, regional health director of Hardap Region. She is one of twenty-five existing and emerging leaders who meet regularly in Leadership Development Forums (LDFs). Deputy Permanent Secretary Dr. Norbert Forster smiled when he recounted the progress of that team. “There was a rigidity in the way that the department worked, with different departments in silos, and there was a disconnect between the national level and the thirteen regions,” he says. “The process we went through focused on breaking down barriers through workshops and retreats. People have gotten to know each other. Through joint sense-making and visioning, we have developed a cohesive team we didn’t have before. By the end of this process, there will be a major change in organizational culture, from working in silos to working in teams.”

Overall, the Namibia process helped to get the system from 1.0 (each part contained within its own silo) to 2.0 (being more responsive to patients) and 3.0 (cross-silo collaboration in the RDUs).

Moving to 4.0, to a system driven by the goal to strengthen the sources of health of the whole community, of all citizens, is still a task for the future. Which brings us to the next stop: Denmark.

Regional Health Transformation in Denmark

In the fall of 2010, the leadership team of a large Danish university hospital came to Boston to conduct a leadership workshop. Supported by our Danish colleague Karen Ingerslev, the group conducted stakeholder interviews before arriving in Boston. Stakeholder interviews help decision-makers to see their roles through the eyes of their stakeholders. One of the main insights that the leaders took away was that their role as hospital leaders was not limited to their own hospital, but was connected to the quality of health in their entire region.

The following year the group suggested a follow-on workshop with the entire leadership team in central Denmark, including the management teams of all the smaller hospitals in the region. It was a very interesting process that allowed me (Otto) to observe a rapid transformation from ego-system awareness to eco-system awareness up close.

The stakes for these leaders were very high. Hospitals were being merged and/or closed left and right in order to reduce square footage amid stagnating budgets and increasing performance pressures from stakeholders. As Ole Thomsen, the leader of the group, put it: “The problem is we have systems that we cannot put more money into. Our challenge is how we can develop more quality with less resources.”8

Every one of them felt enormous pressure to fight on behalf of their home organization to hold on to existing positions, functions, and funding streams. How do you build trust in an environment where competitive and survival genes are hypercharged?

We started with sensing. Over several weeks the group conducted stakeholder interviews and sensing journeys. The workshop started by synthesizing their insights from the sensing activities through café conversation, modeling, and stakeholder mapping. Later we asked them to use Social Presencing Theater to enact how they saw the current system and how they saw the future that wanted to emerge. Social Presencing Theater is a method developed under the leadership of Arawana Hayashi at the Presencing Institute; it blends elements of mindfulness, theater, dance, dialogue, social sciences, and constellation work.

When they mapped out current reality—which we call Sculpture 1—they quickly formed a constellation that looked very institution-centric, with the management teams of each hospital in control at the top. Then, when we ask them to draw Sculpture 2, another constellation that represents the future of the system that they feel is wanting to emerge, the group moved the relationship between patient and care provider into the center of the health-care system. Interestingly, we noted that Sculpture 2 showed two interconnected spheres. The first sphere was related to health care and put the patient at the center; the second, adjacent sphere was related to sources of health and put the citizen (not the patient) at the center, surrounded by relationships with family, civic organizations, and community.

As they morphed from Sculpture 1 to Sculpture 2, the management teams of the hospitals saw their own role changing. In Sculpture 1, the hospital managers were between the department heads and the nurses and physicians, blocking the direct connection between health-care providers and citizens (not patients). In Sculpture 2, one part of the hospital management teams left their position and reached out to citizens, communities, and civil society, while others moved in the opposite direction in order to jointly form a holding space for the new relationship between health-care providers and patients and citizens.

In the language of table 9, we can see Sculpture 1 as an enactment of managed care (health 2.0), with the patient experience fragmented by many competing hospitals and entities. Sculpture 2 has elements of health 3.0 (integrating the various provider institutions to optimize a seamless patient journey) as well as 4.0 (reaching out to the citizen space and citizen journey and creating a holding space for the entire health eco-system).

Although this started as an exercise, what was most inspiring was that these health-care workers then put some of their ideas to work. They told their leaders: “We appreciate your leadership, but you could better use our expertise if you asked us some key questions instead of just imposing solutions on us. That way we could co-create the solution together.” After hearing that suggestion, Ole Thomsen was inspired to change the way the regional leadership team operates by conducting several regular meetings in the form of case clinics.9

The workshop ended with the group developing five prototype initiatives. In only two months they achieved some astonishing results, including taking the first steps toward replacing the financial model, based on activity and productivity targets (“the more procedures we perform, the more money we bring in”), with one that puts the health of citizens and patients first. This required a shift in mindset from ego-system (“the more for us, the better”) to eco-system awareness (“the better for patients and citizens, the better for all of us”).

When I (Otto) saw the same group present this and other prototyping results two months later, I understood a little better why the Danes, Finns, and Swedes rank so highly, as mentioned before. It’s their leadership culture. They are not afraid to challenge one another. And when challenged, they listen to one another. The leaders are willing to listen to subordinates and to conflicting stakeholders and to give credit to useful points of view. They are willing to put their egos aside for just a bit and to listen and think about what might be in the best interest of the entire region. It’s not easy. It’s hard work. But it’s possible. I saw it happen as I watched. And that may well be the most important message from Northern Europe to the rest of the world today: It’s possible. Just do it!

EDUCATION 4.0

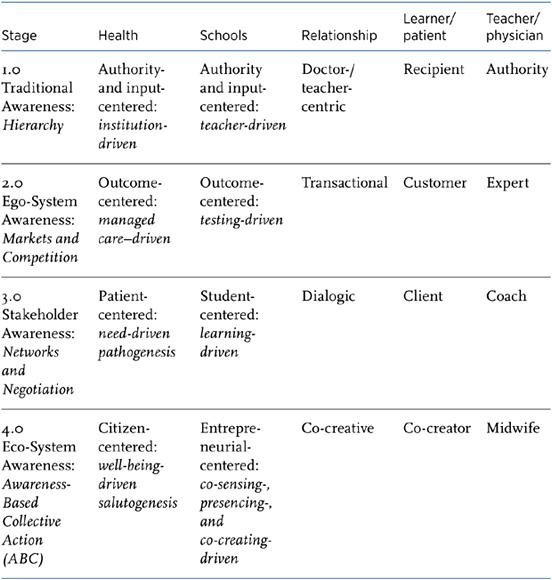

Just as the transformation of a health-care system revolves around transforming the relationship between patient and health-care provider from doctor-centric (1.0) to co-creative (4.0), the education system is likewise going through a transformation process that revolves around the relationship between learner and educator (see table 9).

Accordingly, the institutional transformation of the education system is a journey from

1.0: an input- and authority-centered, teacher-driven way of organizing, to one that is

2.0: outcome-centered and testing-driven, to one that is

3.0: student-centered and learning-driven, to one that is

4.0: entrepreneurial-centered, co-creative, and presencing-driven.

Vienna: Reinventing the Educational System

One of the first times I (Otto) met the Austrian minister of education and culture, Claudia Schmied, and her ministry team, was during a half-day workshop. We were sitting at a long rectangular table. The minister and her dynamic young assistants sat opposite me at the head of the table. Next to them, on one long side, were all her department heads, people who had spent most of their careers inside the ministry; across from them, on the other long side, was a group of school innovators from Germany and Austria. As I looked at the school innovators and the department heads facing each other, it felt as if the twenty-first century were meeting the nineteenth, with the minister and her team in between. The minister was full of energy and inspiration. She came to her job from a business and organizational change background—not a typical party career. I silently wished that her good energy would never dissipate.

Fast-forward a year. I was back in Vienna, this time for a countrywide network meeting of education innovators from throughout the system. Instead of 10 grassroots innovators, there were now 250. There were fewer ministry people, but they were still visible. Somehow the whole educational system seemed to be present. During that meeting we asked everyone to reflect on three aspects of the educational system: the changing learner-teacher relationship; the school as a learning organization; and the countrywide system as a whole.

It took the local innovators only an hour or two to establish that they all agreed on 80 or 90 percent of the changes the system needed, but that none of these changes were reflected in the political discourse in the country. There was a complete disconnect between the education innovators at the school level and the national political discourse.

Fast-forward another year. This time another group of 250 change-makers met in Alpbach, Austria. Before Minister Schmied arrived, we held a first session in which we asked participants where they saw a world that was dying and where they experienced a world wanting to be born. What was dying, they said, was “the teacher who transfers knowledge, who acts as a single player. … ” What was being born was “the teacher as coach and team player.”

“What is dying is a pedagogy that revolves around techniques and recipes. What is being born is a pedagogy that revolves around sensing and actualizing the best potential in students.”

“What we need to let go of,” added others, is “thinking of school in terms of lessons or periods” and “a culture of regulation and control. What we need to develop is a new form of equal collaboration among parents, teachers, and students.”

A third cluster of statements focused on evaluation. “There are many good things in the system, but the focus on standards and outputs is killing the new; the old standards of evaluation impose their stamp on the new.”

And a fourth cluster focused on the system as a whole: “We are constantly tinkering with rebuilding the school; we are replacing a window here and another door there—but what we really need is a new foundation for the entire house.”

When I heard these comments, I realized that the minister’s efforts had not been in vain. Somehow she had managed to bring all of the players into connection with one another. The practical outcomes and accomplishments were nothing short of amazing. Against the combined resistance of the conservative establishment and the teachers’ union, the minister and her team managed to first prototype and then scale her concept of the New Middle School, one among several key initiatives that she used to bring the Austrian education system into the twenty-first century. She also focused on building individual and collective leadership capacity throughout the system.

Claudia Schmied, who travels the country on regular listening journeys, embodies a new breed of political leadership: independent, professional, self-reflective, inspired, courageous, and playful in taking on powerful vested interests in her country. To me she demonstrates that there are no limits to how big our impact can be if we connect to the deep intention of our journey.

Minister Schmied reflects on the journey of systemic change she has been witnessing and leading:

The school system in Austria still has many System 1.0 elements, including a culture of centralized regulation and control. The authorities are supposed to fix the problems. Moreover, we increasingly see elements of System 2.0, where demographic changes (fewer students) or choices by parents create competition among schools. Elements of System 3.0 are very strongly developed in the Austrian educational system, for example in the political power that the teachers’ union has over all key educational topics in the country.

But the goal should be to realize the qualities and mental models of System 4.0. If we succeed, all school partners will focus on creating a successful school; teachers will see themselves as “Zubin Mehtas,” as conductors and orchestrators of the highest creativity in their students; students will experience co-shaping the system. The foundation of System 4.0 is the common will. That means moving the relational dimension to center stage. This is what matters most. It’s about what our schools of the future will be able to perform in order to serve the individual and communal well-being.10

Reinventing an education system for the now-emerging 4.0 world requires more than improving test scores or adding some new classes to the curriculum. It requires a common will, as Claudia Schmied puts it, to renew the very foundation of the whole house, of our entire educational system. It requires an understanding that the essence of all real education is transformation, tapping our deep capacities to create and providing resources for “transformative literacy.”11

Wherever you go, people believe their educational systems are in crisis. Some systems see a crisis of performance: They want students to perform better on standardized tests (Education 2.0). Others see a crisis of process: They want to make learning more student-centered, turn teachers into coaches, and so on (Education 3.0). And a few want to provide learners with the chance to achieve their highest future potential as human beings, to have access to their best sources of creativity and entrepreneurship. They see a crisis of deep human transformation (Education 4.0).

It’s a transformative journey that today is more readily available and more called for than ever before. Nietzsche captures the essence of that journey with a few simple and beautiful lines in Thus Spake Zarathustra, where he talks about the three metamorphoses of the spirit:

Of the three metamorphoses of the spirit I tell you: how the spirit becomes a camel; and the camel, a lion; and the lion, finally, a child. …

What is difficult? asks the spirit that would bear much, and kneels down like a camel wanting to be well loaded. What is most difficult, O heroes, asks the spirit that would bear much, that I may take it upon myself and exult in my strength?

All these most difficult things the spirit that would bear much takes upon itself: like the camel that, burdened, speeds into the desert, thus the spirit speeds into its desert.

In the loneliest desert, however, the second metamorphosis occurs: here the spirit becomes a lion who would conquer his freedom and be master in his own desert. Here he seeks out his last master: he wants to fight him and his last god; for ultimate victory he wants to fight with the great dragon.

Who is the great dragon whom the spirit will no longer call lord and god? “Thou shalt” is the name of the great dragon. But the spirit of the lion says, “I will.” “Thou shalt” lies in his way, sparkling like gold, an animal covered with scales; and on every scale shines a golden “thou shalt.”

My brothers, why is there a need in the spirit for the lion? Why is not the beast of burden, which renounces and is reverent, enough?

To create new values—that even the lion cannot do; but the creation of freedom for oneself and a sacred “No” even to duty—for that, my brothers, the lion is needed. …

But say, my brothers, what can the child do that even the lion could not do? Why must the preying lion still become a child? The child is innocence and forgetting, a new beginning, a game, a self-propelled wheel, a first movement, a sacred “Yes.” For the game of creation … a sacred “Yes” is needed.12

The crisis of our educational system is that, at best, it treats our students as burden-laden camels. Missing is a deeper understanding of the human journey, needed in order to co-create learning environments that enable the learners to shift their state of operating from a burdened camel to “the praxis freedom” that is, from “Thou shalt” to “I want,” and then from the state of the lion (“freedom from”) to the state of the child, the sacred Yes (“freedom to”) that allows us to access the deepest level of creativity.

Some people say, “Oh, well, maybe this 4.0 thing, this transformation of the human spirit—maybe that’s just for the elite—the few, not the many.”

Well, that’s not our experience, or our belief. When you invite people to moments of stillness in order to investigate their deep developmental journey—their “evolving self,” as Harvard’s Robert Kegan would put it13—you find that most people today are very open to such an inquiry. We have been very surprised how open and interested younger leaders in particular are in inquiring into deep layers of awareness and knowing. We have experienced almost no pushback when introducing these concepts, methods, and tools in our work with farmers, teachers, health workers, communities, companies, and governments across generations and cultures—even though most of them didn’t know any of these methods beforehand.

So what does all this suggest? We think it suggests that the real limitation is not “out there” in the world but in our heads, in our assumption about what might be possible. The common will that Claudia Schmied talks about to regenerate the entire foundation of our educational system has never before been more accessible and possible.

Table 10 depicts the parallels in the systemic transformation of education and health. Both systems go on a journey from an authority-centered, input-driven way of organizing (1.0) to one that is testing-centered and output-driven (2.0), then to one that is student-centered and learning-driven (3.0) and to one that is entrepreneurial, co-creative, and presencing-driven (4.0). Throughout this journey, the core axis of the system—that is, the axis between student/patient/citizen and teacher/doctor/nurse—shifted from being teacher/doctor-driven (1.0) to transactional (2.0) to dialogic (3.0) and then to co-creative (4.0). In the language of Nietzsche’s three transformations of the human spirit, we can relate the burden-carrying camel (“Thou shalt”) to the first two relationships, while the lion relates to 3.0 (“I want”) and the child or self-propelling wheel belongs to 4.0 (the sacred “Yes”).

TABLE 10 Parallels in Education and Health Systems Transformation

Beijing: Leading Learning Communities in the Chinese Government

This may sound hopelessly idealistic, and some of you may be tempted to roll your eyes as you read this. But we believe that the few emerging 4.0 examples that we report on in this book are just exemplary pieces of a much larger shift that is starting to happen around the world. That shift is essentially a shift in consciousness by leaders and change-makers.

The transformation journey of the educational system led by Minister Claudia Schmied in Austria, the transformation of the regional health-care systems in Denmark and Namibia, the transformation of corruption and government services in Bojonegoro, Indonesia, and the transformation of the Secretariat of National Heritage, a quasi-ministry of the federal government in Brazil, are all unlikely stories and examples of a larger pattern. Consider also a group of senior Chinese government officials whom Otto and Peter Senge began working with in 2012.

What touched us in working with them was the sincerity with which they participated in a six-month U process journey. It started with a workshop in China, continued for two weeks at MIT and on related learning journeys on the East and West Coasts of the United States, and then took them back to China for a weeklong retreat workshop. During the second half of the process, they worked in small teams to co-create five prototype initiatives. When they first explored their prototype initiatives through the method of Social Presencing Theater, they realized that they needed to change or evolve the role of government in the system. The old role of government was to be at the center and provide solutions that would meet the needs of the citizens. The new role of government, which these leaders learned more about in their prototyping work, started with a space of deep listening, in which they heard the concerns of the citizens and all other relevant stakeholders. In this co-creative space, stakeholders could co-generate the solutions that best met their needs.

Everyone was impressed when the Chinese officials shared their results and learning experiences. But especially moving was a three-hour circle in which they shared their personal thoughts, reflections, and takeaways at the end of their six-month journey (during which each of them continued working in their usual day jobs). Here are several quotes that Peter recorded while we sat in the closing circle:

“The changes I notice in myself, to be calmer, may be subtle, but they are profound.”

“Can I really let go?”

“Am I open?” “Is my heart open?”

“What is moving me is this group.” “Everyone is my teacher here.”

“What is moving for me is the authenticity in ourselves; the harvest [of this] is real community.”

“What moved me was the dissolution of boundaries.”

“I can feel my inner self changing. I can feel it … to think and feel from the inner self.”

“The most important lesson to me is to listen.”

“The more we learn here, the more we question ourselves.”

“This is not just learning something tangible; it is learning to change the state of ourselves.”

“As citizens of the earth, [we] can feel incapacitated [by the magnitude of the problems]. But when we are connected to our world, we feel strong.”

“I believe this will have a long-lasting impact for my country.”

“The problems that appear [in our work] are a chance for deeper thinking.”

These reflective observations have led us, and Peter, to explore with our Chinese partners how this type of work could be organically developed, localized, and scaled in the Chinese context as needed. With the possible exception of global business, there probably is no institution on this planet other than the Chinese government that could have a more significant positive impact on pioneering a sustainable economy that works for all.

COMPANIES 4.0

What does this emerging shift in context and consciousness mean for transforming and revolutionizing what many consider to be the most powerful institution on this planet: business? Many companies have gone out of business because they stopped being adaptive and relevant; and even more are at risk of going that same route. So what does the journey to a possible 4.0 enterprise look like?

Here is a nutshell version of the journey to 4.0 in business, which we illustrate with real-life examples below. It moves from, generally speaking,

1.0: owner-driven with centralized control; to

2.0: shareholder-driven and decentralized and divisionalized; to

3.0: stakeholder-driven and networked and matrixed; to

4.0: an intention-driven co-creative eco-system.

BALLE: Creating a Nationwide Movement Out of the White Dog Café

The Business Alliance for Local Living Economies (BALLE) has twenty-two thousand members and is the fastest-growing network of socially and environmentally responsible businesses in North America.14

The origins of BALLE lead us to the White Dog Café in Philadelphia, and to its founder and owner, Judy Wicks, author of the memoir Good Morning, Beautiful Business.15 Over the course of twenty-five years, Wicks pioneered a series of groundbreaking business practices, including direct partnering relationships with local farmers and sustainable and local sourcing. The White Dog Café paid all its staff a living wage, took customers on learning journeys to the farms that supplied the café’s food, and organized eco-tours to show customers where waste from the restaurant went, where municipal water in Philadelphia comes from, and where the energy they use is generated. The White Dog Café became the first business in Pennsylvania to source 100 percent of its electricity from renewable energy.16

As she adopted these practices, the White Dog Café became more prosperous and successful. But instead of resting on that success, Wicks decided to do something different. She realized that if she really cared about the well-being of her community and environment, she needed to share her business practices and help her competitors learn how to do what she was already doing. Wicks remembers the moment when she realized that Business 3.0, doing socially responsible things, just wasn’t good enough anymore: “It was a transformational moment when I realized that there is no such thing as one sustainable business, no matter how good the practices were within my company, no matter if I composted and recycled and bought from farmers and used [renewable] energy and so on, that it was a drop in the bucket. I had to go outside of my own company and start working in cooperation with others, and particularly with my competitors, to build a whole system based on those values.”17

In order to move into this 4.0 environment, Wicks established the White Dog Café Foundation, which she funded with a portion of the profits from her restaurant. The first thing she did was ask the farmer who supplied her restaurant with two organically raised pigs each week what he would need in order to be able to supply other restaurants as well. When he told her that he needed a refrigerated truck, she loaned him US$30,000 (from her own restaurant’s profits) to buy the truck so he could begin to supply all of her competitors with the same quality of pork.18 The first project of the foundation was Fair Food (www.fairfoodphilly.org), which had the original purpose of providing free consulting to White Dog’s competitors—chefs and local restaurant owners in Philadelphia—to teach them how to buy humanely raised pork and other products from local family farms and why it was important.19

Also under the umbrella of the foundation, in 2001 Wicks launched the Sustainable Business Network (SBN) of Greater Philadelphia in order to spread the business practices of the White Dog, and in that same year she partnered with others to co-found the Business Alliance for Local Living Economies (BALLE) to build a network of place-based businesses using these practices that could grow into a viable alternative to the corporate, chain-store economy.

The BALLE movement demonstrates how local businesses can succeed through increased cooperation rather than competition. The pioneers and entrepreneurs who are willing to share proprietary information about their operations, their practices, and the needs of their businesses while helping others in their sector are improving the well-being of the larger eco-system while also advancing the well-being of their own enterprise.

Natura: Shifting the Field of Business

Natura is a multibillion-dollar Brazil-based skin care and cosmetics company that has been a leading innovator in sustainable development in Brazil and Latin America. When the company sources raw materials from Brazil’s forests, Natura makes sure extraction happens in an environmentally and socially sustainable way and that the activity does not disrupt local cultural traditions. The company has also created profit-sharing arrangements that make sure some of the surplus is reinvested in the sustainability and cultural resilience of the Amazon communities who work at the very beginning or origin of Natura’s value chain. These profit-sharing arrangements with communities in the Natura eco-system are operated through self-governed community foundations in the communities themselves. Natura also invests in education and capacity building throughout its eco-system of partners and stimulates their partners to also work with other companies, so communities do not become economically dependent solely on Natura.20

In the 1970s and 1980s, Natura developed a direct sales model that empowered community members. Today its products are sold through 1.5 million micro-entrepreneurs and beauty consultants who resell Natura products in their own communities.

Just as the BALLE movement can be traced back to kitchen conversations in the White Dog Café, the origin of Natura can be traced to inspired conversations in a tiny generative space many years back. In 1969, then twenty-six-year-old Luiz Seabra stood in front of his studio in São Paulo, handing out white roses to women passing by on the street. Then he walked them, white roses in hand, from the street into the studio to engage them in conversation and provide a free consultation on the new skin-care and cosmetic products that he just had prototyped. “I fell in love,” remembers Luiz, “with relationship and beauty.”

And he has been in love ever since. I (Otto) met Luiz in November 2011 in São Paulo. Luiz is now in his late sixties, but his youthful, joyful energy still radiates from his whole being. Relaxed and dressed in jeans in the office building that he shares with his two Natura co-founders, he remembers how it all began.

“When I was twelve years old, I observed my sister using skin care. I had a strong feeling in my heart that one day I would create these products.” Fourteen years later he was passing out white roses, inviting women into an inspirational relational space that enchanted them with a different kind of connection to their bodies, to their beauty, to one another, and to themselves.

“The white rose,” explains Luiz, “is a symbol of what we would like to offer. What is your gift? What is our gift? Like the caterpillar that morphs into a butterfly, the gift that we bring into this world also morphs and changes.” It needs, says Luiz, loving attention to find “its own path to beauty, the path to a butterfly.” That loving attention, according to Luiz, is the essence of Natura. “It’s about a conversation and relationship where we are touched by presence and beauty.”

Listening to Luiz, I felt the presence of a worldview that values beauty and truth equally. That really struck me. It’s what I like about Nietzsche. Most people today don’t understand that beauty is primary to truth. They don’t see that the essence of mathematics is beauty, that the essence of science is beauty. To find that essence, you have to follow math and science all the way to their source. Luiz is that guy: He went straight to the source. As a twelve-year-old, he began listening to his sister from an open-heart connection.

But how did Luiz apply this deep level of attention and listening to the task of building a US$4.5 billion company with 1.5 million resellers and touching the lives of more than 100 million consumers on any given day? You do that, replies Luiz, by not only focusing on managing numbers or managing others, but by “facing yourself” with an open mind and an open heart—in other words, by bending the beam of observation back onto yourself. The problem in many organizations today, says Luiz, is fear. And “the only antidote to fear is love.” When we judge others, we create an atmosphere of coldness that opens the space for fear. Transforming that atmosphere of fear requires us “to connect with our sources of presence, our open heart.”

Listening to Luiz is a joyful experience because he clearly enjoys the moment. He is very visibly still enchanted by the world; he is still in love with relationships and beauty. It’s rare for a man (or anyone else) to so powerfully embody the presence of the open heart.

So, I wonder, how did he get here? What process brought him to this state?

“I am very shy,” he responds. Really? “But I am enchanted with the world.” That was quite visible. But how did he get here?

“I too had too much noise in my head,” recounts Luiz. “So it was essential to find a silence within myself.” He first found that silence by experiencing a shift of mind and heart while reading a philosophical text as a sixteen-year-old. In that text Plotinus suggested that “the One is in the Whole, the Whole is in the One.” It dawned on Luiz then that this deeper level of reality that Plotinus referred to requires a deeper level of thought—a thinking that is powered by the intelligence of the heart. This moment of insight opened up a whole new world for him. It was an intellectual and also a spiritual experience that allowed him “to find a silence within myself.” Connecting to that place was like “finding a new life inside myself, a new birth.”

Ever since, he has tried to operate from that connection to essence in that quiet place. Many of the normal management tools, like managing by the numbers or managing by market share, are just a perpetuation of noise. “The use of these traditional management instruments makes us less intelligent.” Good point, I thought when writing this down—it means that normal business schools are dumbing us down. So why would you pay for that?

“It’s time to listen to our silence; to share it, we need a kind of massage.” And in order to cultivate this inner silence, “we must have filters against excessive banality.” That will help us to “transform fear into love.”

Later that morning, I met his business partner, Guilherme Leal, another co-founder of Natura. After merging his own company with Natura in 1979, Guilherme helped build Natura into the largest direct-sales cosmetics company in Brazil. What struck me most was seeing how these two men interacted with each other. Often very successful and high-net-worth people tend to go it alone. Instead these two men seemed to have a relationship that was delicate, respectful, caring, appreciative. None of these words really get to the essence. If I had to choose a single word, maybe it would be selfless. They seemed to genuinely enjoy their differences and to support each other in them.

For all of the company’s success, today it faces a new set of opportunities and challenges. Like all companies, Natura faces disruptive challenges in business and society. Additionally, the founders are playing a less active role in its everyday leadership. One current challenge, therefore, is how to keep the essence of Natura alive in this new context. Another challenge is to reinvent the direct selling strategy in the age of Web 2.0 business models. How can Natura become a platform that allows the entire eco-system of suppliers and consumers to co-sense and co-create to their highest future potential?

“Natura is a collective phenomenon,” says Marcelo Cardoso, senior vice-president for sustainability and organizational development, “and today we are [on] the threshold of a new evolution cycle.” The new evolutionary cycle that Natura and the whole business community face concerns the emerging 4.0 co-creative eco-system economy. The heart of the future eco-system-based company is no longer a particular product offering; instead it is a cultivated web of “multiple connections and relationships that we have with each other as partners, producers, users, owners, shareholders, and community. The radical vision we try to bring about puts the sacred relationship to our partners and customers into the very core of the company.”

Marcelo suggests that three main principles characterize the 4.0 way of organizing. The first one concerns the need to influence by attraction rather than control. The second concerns tolerance for uncertainty. And the third concerns removing the 2.0 system of bonuses. “We found that in Silicon Valley no one is using bonuses linked to individual targets,” Marcelo says. “In the future we will replace our individual target and bonus system with five goals for the entire company that tell the story of the company. In the future we will have more fixed and less variable compensation.”

This shift in Natura’s compensation system is backed by a lot of scientific evidence that suggests that individualized remuneration is doing more harm than good to the performance of companies, except in cases of very simple and mechanical routine operations with little creativity involved.21 In essence, Marcelo sees the current transformation of Natura in terms of outside-in and inside-out. Outside-in means making the cultivation of relationships the center part of the future company. Inside-out means to let go of control, to let go of individualized targets and bonuses, and to come up with more intrinsic and co-creative mechanisms of motivating, direction setting, and innovating, often done jointly with the eco-system partners. Is that an easy process? It’s not, and Marcelo will be the first to point out that he sees himself and Natura at just the beginning of that journey.

Food Lab: Shifting the Field of Food

BALLE and Natura are great examples of partially mission-driven enterprises that are moving in the direction of 4.0. But what about more traditional companies? What will it take for them to make the shift to 4.0?

The Sustainable Food Lab is pioneering solutions in this domain. The Food Lab is a forum for leaders across the system to address the most pressing and significant problems of food and agriculture.

In the summer of 2002, Hal Hamilton, Don Seville, Adam Kahane, and Peter Senge met over breakfast at a global leadership conference. They started exploring the possibility that the polarized debates over agricultural sustainability might benefit from the application of Theory U. The conversation later expanded to include leaders from Unilever and the Kellogg Foundation, who described their ongoing investments in sustainable agriculture projects and their desire to influence the mainstream. They noted, however, a sense that neither the Kellogg Foundation nor Unilever was powerful enough to do this alone.

In the year and a half that followed, Hal, Adam, and their colleagues interviewed dozens of system leaders in the United States, Europe, and Brazil. From these interviews, individuals were invited to join the Food Lab. Incorporating advice and experience from many interviews and meetings, the Sustainable Food Lab was launched with the purpose of making mainstream food systems more sustainable.

The lab brings together leaders from more than sixty businesses, governments, farm groups, and NGOs with this explicit focus. Although a sustainable food system is at the heart of its work, the group realizes that perspectives on what it means to be sustainable differ substantially among the institutions, businesses, and organizations represented in the lab. One of the challenges for the lab team is to use these differing perspectives and priorities as a catalyst for shared learning and significant innovations in the system.22

We asked Hal, now the co-director of the Food Lab, what he has learned from recreating infrastructures that help organizations to collaborate and innovate their way to 4.0. “What we have learned,” Hal says,

is that to move a whole eco-system of food suppliers toward sustainability takes a new type of leadership support structure. We have found three particular leadership or learning infrastructures to be effective. The first one we call learning journeys. We take diverse groups of stakeholders to the interesting spots and edges of their system and give them a deep immersion experience for a day or two. That has always been so successful, regenerative, and in part even transformative.

Second, we have found that it is mission-critical to engage our members in concrete prototyping projects on innovation issues that link well with the strategic agenda of these organizations. If these projects are just of personal interest but not institutionally relevant, then these initiatives can’t be sustained and can’t go to scale.

And last, we found that there is a deeper personal or human dimension at work in all of this. I am not sure how to name this. But it has to do with the fact that we have created a deeper web of human relationships that crosses all these institutional boundaries. This different web of human relationships is not just about feeling better and having more energy. It is essentially about having a different relationship to our own journey, to the journey of your community, and to the journey of our planet. So it’s a field that allows you to reconnect with your essence.

In addition to these three learning experiences articulated by Hal, there is a fourth one that he didn’t mention: Get the right people with a 4.0 mindset into the core group of such an enterprise. The people must embody the essence of the initiative with everything they do—like all of the change-makers whose stories we’ve told in these pages: Jon, Suyoto, Alexandra, Claudia, Judy, Michelle, Luiz, Guilherme, Marcelo, Hal …

Summing Up

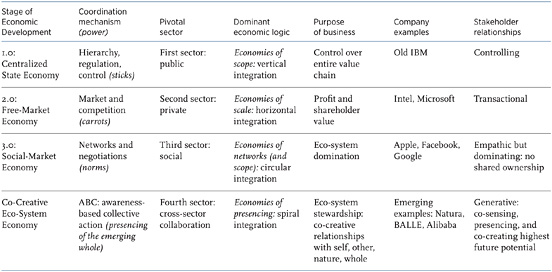

Table 11 outlines how the evolution of the corporation is embedded in the evolutionary stages of economic development and its underlying logic. The purpose of the 1.0 company is control over the entire value chain. The logic revolves around economies of scope; the focus is on vertical integration (for example, the old IBM). The purpose of the 2.0 company is profit. The logic revolves around economies of scale, and the focus is on horizontal integration (for example, Intel and Microsoft). The purpose of the 3.0 company is eco-system domination. The logic revolves around network economies. Examples are Apple, Facebook, and Google. The purpose of the 4.0 company is eco-system stewardship. The logic revolves around economies of presencing—that is, around sensing and actualizing emerging futures. Emerging examples of this category include BALLE, Natura, and the Chinese e-commerce giant Alibaba. The difference between 3.0 and 4.0 companies is intention: 3.0 companies are driven to dominate their eco-system, while 4.0 companies try to serve the well-being and shared ownership of all. The 3.0 and 4.0 corporations are a new breed of hybrid companies that have two main characteristics: They function as a business, and they are inspired and energized by a social mission (in 4.0 companies, the mission is more strongly embodied). This is not just a marginal feature of the business community. Think about what inspired visionary founders like Steve Jobs at Apple; Eileen at Eileen Fisher Inc.; Luiz, Guilherme, and Pedro at Natura; Judy and Michelle at BALLE; and Hal at the Sustainable Food Lab. These ventures are exemplars of an emerging “new essence” of what it means to run a successful enterprise. In this emerging business paradigm, success is defined not only by profit, but also by its relevance to the larger eco-system and its practical contributions toward bridging the ecological, social, and spiritual divides. Interestingly, some of these hybrid, social-mission-driven companies increasingly look and feel like some of the more innovative NGOs.

TABLE 11 Stages of Economic Logic and Corporate Development

NGOS 4.0

With the collapse of the Berlin Wall and the end of the Cold War, a transition to a new era began that has seen the rise of an emerging new superpower: global civil society.

Since the late 1980s, millions of NGOs and CSOs (civil society organizations) have emerged on all continents. This movement, in the words of Paul Hawken, is the largest the planet has ever seen.23 The NGO and civil society sector is the most recent arrival on the global stage. With the founding of the United Nations after World War II, governments went global, and with the surge of globalization, particularly after 1989, business went global in successive waves. In a nutshell, here is how civil society expresses itself through this new class of institutions and its developmental journey:

1.0: NGOs: alleviating actors, donor-dependent

2.0: NGOs: policy advocates, donor-dependent

3.0: NGOs: multistakeholder or social mission enterprises, partly self-funding

4.0: NGOs: eco-system innovation enterprises, partly or fully self-funding

WWF

The World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF; formerly the World Wildlife Fund) is an international NGO whose purpose is the conservation of our environment.24 With over 5 million supporters, WWF is working in more than 100 countries worldwide and is the world’s largest independent conservation organization. Its mission is to halt and reverse environmental destruction.

During my (Otto’s) first visit to the US headquarters of WWF, COO Marcia Marsh explained the evolution of the organization’s work. She said:

First we were all about conserving the environment. Then we realized that in order to do that, we needed to include the communities that were living in these areas. We cannot do it without them. Then we realized that even that is not enough. We realized that the real forces that destroy our habitats and commons have little to do with the local communities and a lot to do with the forces of global markets. So we realized that in order to protect the environment, we had to work both with local communities and with global markets—that is, with global companies as well as with conscious consumer groups that would help to shift the corporate sourcing practices toward sustainability.

The three stages that Marsh described track the evolution of WWF from 1.0 (environmental protection only) to 2.0 (including the communities) to 3.0 (including the markets). In terms of challenges, that means that the closer you get to the current edge of the work, “the more you deal with complex, system-wide multistakeholder issues that no individual sector, let alone institution, can change alone.” Says Marsh: “That is why we need multi-stakeholder initiatives to make it happen.”

One example of the new type of multi-stakeholder work is the Coral Triangle Initiative (CTI). The Coral Triangle in Southeast Asia is unrivaled among the world’s ocean environments for its biological significance and its beauty, and it is prized even more for its economic value to the 125 million people in the region, which includes six countries: Indonesia, the Philippines, Malaysia, Papua New Guinea, the Solomon Islands, and Timor-Leste. In May 2009, the leaders of these six countries committed to the ten-year Coral Triangle Initiative Regional Plan of Action, one of the most comprehensive, specific, and time-bound plans ever put in place for ocean conservation.