Chapter 16: Standard Forms and Contracts

(excerpted from Managing the Design Process books by Terry Lee Stone)

CREATIVE BRIEFS ARE STRATEGIC TOOLS

Computer scientists have a saying, “Garbage in, garbage out.” It means that computers can process a lot of data output, but it will only be as good as the information that was put into the system. It’s pretty much the same in design. When creative is developed from great client input, the results can be great. If not, well, it’s a recipe for falling short of the mark. Without a well-identified and articulated set of objectives and goals that is rooted in thorough background and research information, a design can’t grow out of a solid foundation. There needs to be a summary of all the factors that can impact a design project. It is well worth the time it takes to develop it.

What’s in a Creative Brief?

In the best cases, a creative brief is created through meetings, interviews, readings, and discussions between a client and designer. It should contain background information, target audience details, information on competitors, short- and long-term goals, and specific project details. A creative brief will answer these questions:

• What is this project?

• Who is it for?

• Why are we doing it?

• What needs to be done? By whom? By when?

• Where and how will it be used?

Without making a framework for the project, the designer won’t be able to understand the parameters or context that needs to be worked within. The creative brief provides an objective strategic tool that can be agreed and acted upon. It can serve as a set of metrics by which to judge and evaluate the appropriateness of a design. At the very least, all the relevant project information is contained within a single document that can be shared as guidelines for the entire client and designer project team.

Negative Impact of No Creative Brief

Any designer who simply launches into a design assignment without a proper briefing doesn’t have all the relevant facts and opinions to do a well-informed job. They are also asking for trouble as work progresses. Approvals come with buy in; buy in is so often a result of feeling included and asked for input. Sure, the odds are that they can design something interesting and eye-appealing based on their gut instincts, but these solutions are not grounded in solid understanding, and they are more easily dismissed by both clients and target audiences.

• Develop a list of questions for a client that will provide you with the information you need to proceed with the design.

• Ask the client to identify a list of people in their organization who should participate in the briefing process.

• Do client interview session(s). Meet the selected people one on one for more candid responses. Send clients the questions in advance so that they are better prepared to respond.

• Take notes and/or record the interviews. Having two design team members on hand works better than doing it alone, because it allows the conversation to keep flowing, while still being recorded. Do remember that recording someone without their permission is inappropriate and illegal.

• Compile and analyze the interview findings. Create a summary document. Where is there consensus? Where are the overlaps and tangents?

• Write the creative brief. Include the essential items listed on pages 142–143, and format the document to be easy for both you and the client to use.

• Send the creative brief to the client for approval. Some designers do a design criteria document (see page 146) instead of sending the actual creative brief, which they share only with the design team. Whichever the document, send a summary of findings to the client first before any design begins.

• With client approval, distribute the creative brief to the design team. Some firms do this in a kick-off meeting; others just provide a document. Either way, this is the design team briefing. The creative brief works as the guiding framework and background document to inform all design development.

• Both the client and the design team members should evaluate all design solutions based upon the creative brief. Learn more about evaluating design on pages 164–165.

A creative brief is used not only at the start of a project, but throughout the entire design process. It is the one constant element that has been agreed upon and is objective enough to act as a guideline. Clients primarily use it to get organized, and to develop consensus within their own enterprises. They then use it to determine if the design actually solves the problem it was intended to. Designers use creative briefs to fact-find and understand their client, building knowledge about both perception and reality of the problem at hand. Designers often find out that what their client thinks is the problem is not the problem at all. These are the things that become revealed in the briefing.

Once the creative brief is agreed upon by both the designer and client, it is a useful tool for getting all members of the design team on board and ready to work on the project. The designers have relevant grounding to inform their thinking, the copywriter has messaging information, the production and project managers have milestones and due dates, and the account executive has met and bonded with all client stakeholders. Everyone has what they need to work, no matter what their responsibility is.

Creative Briefs vs. Design Criteria

Sometimes, designers take the extra step of translating a creative brief provided by their clients into a design criteria. If a creative brief is a tool that provides a framework and roadmap for a design project, the design criteria is the summary of the approach and a preplan for the creative. The design criteria describes what the designer will do to solve the problem—i.e., the creative strategy.

Taking the time to develop design criteria is very important if the client is contradictory or indecisive. It gives the designers another opportunity to clarify details before they begin creative work by team members who tend to be the most highly skilled and most expensive in terms of hourly rate. It creates a sureness that designer and client are in agreement.

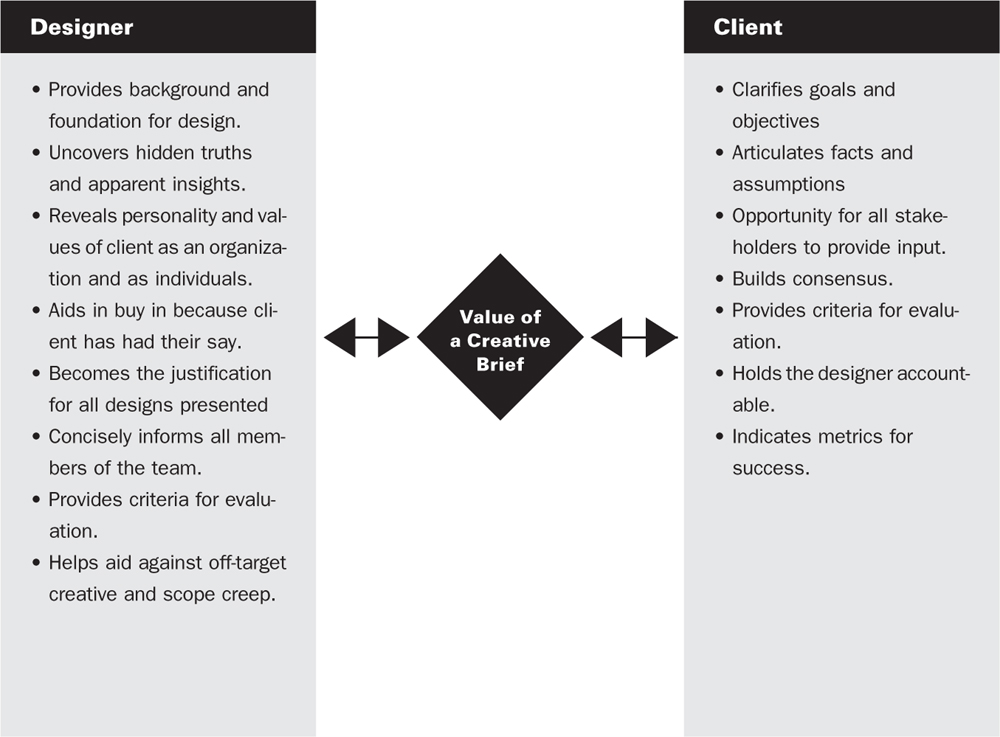

Both the client and the design team use the creative brief. Creating it helps a client crystallize the salient information, gather their thoughts, and research and identify goals and objectives. It provides an opportunity for all stakeholders to give input and have their say. It aids in client buy in of the resulting designs mostly because the client team has all provided input.

For the designer, the brief provides relevant information to alleviate guesswork. Who knows the client’s business better than the client? By gathering this information concisely in one document, the creative brief is a criteria for evaluation, outlining metrics that indicate success, and ultimately holding the designer accountable—unless of course, the designer can convince their client that the creative brief is wrong.

A lot of designers think money is a main reason they win or lose a client’s business. They are often right. Pricing work properly is a skill acquired through practice. It takes a keen instinct for what the marketplace will pay and what the design firm will need.

How the work is priced is only one factor in getting a design job from a client. Other factors from the client’s perspective include

• Relevant Experience: Has the designer worked on a similar project in the past? What does it look like? What are the results of the design?

• Right Attitude: Is the designer enthusiastic and eager to begin work on the project?

• Good Chemistry: Does it seem like a good fit? Does the designer “get us”? Do we like the designer as a person?

• Portfolio/Style: Is the designer’s work appealing? Does it have a discernible style that meshes with our needs? Is the designer creative enough?

• Perceived Reliability: Did the designer show up on time? Do we think we can trust the designer? (Since the client is sometimes meeting the designer for the first time, this is often subjective.)

• A Referral: Did someone we know and trust refer this designer to us? Did the designer get a good recommendation?

• Luck: Is the designer in the right place at the right time?

It is arguable which comes first—creating a schedule or creating a budget. Sometimes a client just tells the designer how much money they have for a particular project. Usually, though, the client requests a price from the designer. The designer’s compensation is an essential element in a designer–client agreement.

Pricing is what you tell the client it will cost for the project. This includes fees (your compensation) and expenses (reimbursable outside costs for items purchased for the project). Budgeting is how you appropriate and manage these fees and expenses. In this chapter, we’ll look at money in both ways.

Here are some key factors to consider when pricing a design job:

• Scope of Work

What exactly are we doing? What services are we providing? What are the deliverables? In what format?

• Resources

Who will do the work? Do we have to supplement our team with additional designers? With what skills? How much do they cost? Do we need our senior or junior designers to do the work?

How much time do we have? How much time do we need? How much time does each team member need? Do we need to juggle several projects simultaneously? How does that affect us?

• The Client

Have we worked for this client before? Are they decisive or prone to revisions? Are there layers of management that must be appeased or is there one decision maker? How available is that person?

• Collaborators

Beyond designers, who else needs to work on this project? What will they do? What will it cost? How much will be provided directly by the client?

• Quality

What are the client’s expectations? Are they willing to pay for it? Have we done something like this before? Will there be a lot of research, or can we immediately get to work?

• Expertise

Do we have it? How steep is the learning curve if we don’t? How will we know when we have a great design for this client?

• Cash Flow

What other jobs are in-house right now? How much money do we need? Design is a business, and all businesses have real financial requirements and obligations. What are ours?

The answers to these questions have cost implications. The more experienced a design manager is at answering and anticipating these tough questions and the better his or her documented records are on previous projects, the more accurate the design manager will be in pricing and budgeting projects.

Determine Your Rate

You can determine an hourly rate for design services in several ways. Many design organizations worldwide have published this kind of information as a reference. For example, in the United States, the AIGA publishes an annual wage and salary survey. You can divide the average annual salary reported in the survey by the number of billable hours in a year (1,500 hours is a good round-number average to use). This calculation gives you an hourly rate based on the organization’s member submission information. A discussion with peers and colleagues may yield a ballpark idea of what they charge per hour. However, many people shy away from this kind of conversation and often don’t tell the truth. If they trust you, and don’t directly compete with you for client business, they may reveal this information.

Calculation Based on Real Needs

Here is a formula for determining your hourly rate based on your actual costs of staying in business.

It’s not the only way to determine an hourly rate, and it doesn’t factor in the value of the work to a client’s business or a premium for your expertise; it’s merely based on actual economic needs.

Reviewing Pricing

Designers must know their hourly rate to set their fee for particular design jobs—both the breakeven hourly rate to understand the lowest fee they should charge, and the published hourly rate to allow for profit and tax obligations (see page 95). Calculating a fee using both sets of rates shows you where the job must be priced (breakeven) and what is an optimum price (published hourly rate). However, it is hard to know exactly how many hours it will take to do any design project. Therefore, any estimate based on hours is just that: an educated guess on the duration and complexity of the work. As such, pricing jobs strictly on hourly rates is not a 100 percent accurate approach.

Evaluating Your Calculations

To get a more well-rounded view of pricing, review the project total you calculated using your published hourly rate and ask yourself the following questions: Does this total reflect the value of this work to the client? Does it reflect the expertise we bring to the project?

Can we get more money for this job based on who the client is? In other words, is this client a small regional startup company or a well-funded multinational corporation? Little businesses typically have little budget, and big businesses should have a big budget. What have we charged for similar projects in the past? How is this project the same or different from those? Is that reflected in this price calculation?

What do we think our competitors would charge for this project? Why do we think that? Can we discuss our calculation with anyone?

(Talking about pricing design with a colleague or two is fine. Note, however, that in most countries, banding together as a profession and determining an industrywide price is illegal. It’s a form of collusion called price-fixing. This is why design organizations as a group rarely discuss in public or publish pricing information.)

Is there any published information on pricing for this type of work? For example, the Graphic Artist Guild’s Pricing and Ethical Guidelines publishes rate information. The organization polls its members, has them price certain kinds of projects, and then publishes that information. It can legally do this in the United States because it is a trade union, and it operates under different laws than nonprofit design (arts) organizations.

Does this price calculation seem high or low based on your gut instinct? How should it be adjusted?

Two design firms can have the same published hourly rate and calculate two different project fees using that rate. For example, one design firm may work slower or have more people involved; this means it estimates more hours into a project and it charges more. Only by keeping very good records, especially time sheets, on all projects and then comparing estimates to actual costs can designers price their work accurately over time.

A trusted client may be candid and tell the designer what competitors would charge on a particular job, particularly if the designer lost the job to a competitor. It’s important to learn why a design firm lost out on an opportunity, but remember that it isn’t always a question of money.

Another useful strategy is to develop relationships with other designers that can include discussions of money.

Remember that big fees don’t necessarily mean big profits. It all comes down to how the project is run. How long did the designer work on the project to earn that fee? Maybe we spent very little time on the project, but the work was tremendously valuable to the client’s business. These things are unique to every design project. It is why most designers are always wondering whether they charged enough on a job and whether they could have made more money.

Clients and Money

Not all designers are driven by money. Scores of designers are much more interested in the artistic than the financial aspects of design. However, all designers need money to survive.

Reframing financial negotiations with clients means designers must be fully engaged in an active conversation with the client. They need to be confident about their ability to use design to meet their client’s business goals; believe in the value of their work; and be willing to ask for fair compensation. Money often coincides with issues of self-worth, so you must believe in yourself and your abilities as a designer before negotiating fees in order to achieve the best outcome financially and creatively.

Tips for Dealing with Clients About Money

• Be clear. What exactly does the price include?

• Define payment terms. When do you expect to be paid? Upon completion? Within thirty days?

• Stick to the fee. If you must raise the fee, explain the increase in a change order.

• State the number of revisions and stick to them. Note any exceptions or additions in a change order.

• Keep good records. Provide time sheets and expense receipts as a backup to your billing if the client requests it.

• Integrate the schedule with regular cost reviews. Review these frequently, and communicate any problems or issues. Alert the client. Make sure you capture all time (e.g., telephone consultation, travel time, etc.).

• Don’t surprise the client. To get paid quickly, make your invoices match your estimates exactly.

• Keep fees consistent. Base fees on a rate the client understands. No fire sales, no discounts, no arbitrary changes in pricing structure.

• Get it in writing. Have anything related to money signed by the client, for legal reasons and to prompt a detailed conversation about money before any work gets underway.

• Get all related client paperwork and financial information. Get a purchase order number if it’s required. Include a vendor number on your invoices if you were assigned one. Introduce yourself to the contact person in accounts payable.

• Stay in communication. Do this throughout the process, with the client contact and the accounting department, if necessary

• Consider incentives. This can be a discount for prompt or fast payment of invoices, or a late fee as a penalty for slow-paying clients.

Questions for Negotiating

Sometimes, a client can’t afford your fee. The question is: what is actually happening? Investigate further:

• Will they ever be able to afford it or is it a temporary problem?

• Do they want to work with you?

• Can the scope to reduce deliverables be narrowed?

• Can they provide you with referrals?

• Will you get a great portfolio piece?

• Will you gain recognition, credibility, or some other benefit besides money?

• Is it worth taking the job?

Sometimes, you may wish to negotiate pricing. Naturally, it needs to be in your best interest to do so. Here are some questions to ask:

• Can we have longer to work on the project, perhaps fitting this job in between other work?

• Will the project challenge us creatively and open new doors?

• Can we do research and learn new skills that are marketable to other clients by doing this job?

• Will we have a chance to work with some exciting new collaborators in brand new ways?

These factors may be interesting enough to you to make it worth dropping your prices to get the job.

Talking Revisions

Communicating with clients about revisions is a huge part of managing client expectations regarding money. The best strategy is to be clear in the designer–client agreement about how many revisions are included. That way, the client understands the meaning of revision and round of revisions, and when they will start receiving additional charges because of those changes.

For more information, see page 40–41.

Even with this clearly spelled out, many designers are unsure how to corral their client and alert them that they have exceeded the planned scope and revision allotment, for fear of losing the client. If the client has agreed to the terms in the designer–client agreement, it is okay to bill them. Just let them know what is happening in a professional manner.

Too often, designers are afraid to ask for additional compensation for additional work.

This makes it harder for the industry to be treated fairly in this aspect of the business. When you practice without fair compensation, including receiving additional fees for additional work, you are hurting not only yourself, but all designers everywhere.

Designer Fault

Some designers hesitate to charge for revisions because they feel they caused the revisions. This may be true. An evaluation will reveal the cause(s) of a revision in a design project. If it is poor performance on the designer’s part, the designer should not charge it to the client.

Ballpark Estimate:

This is an initial rough estimate based on high-level client objectives, with a large margin for uncertainty. The deliverables, scope of work, and corresponding resource requirements may not be clear yet, so out of necessity, the estimate must allow for these things. Typically, a price range, rather than a fixed fee is stated.

Budgetary Estimate:

This is a more accurate view of project-related costs based on a much clearer scope of work. It is contingent on a fairly accurate view of the work to be done, which still may be in a state of flux. As such, conditions and parameters should be stated—for example, “This estimate is based on available information, and will be reviewed based on approved design concept.”

This is a time-consuming and detailed estimate created once the full scope of work, final deliverables, and detailed work flow are known. A full work breakdown structure (see page 66) is completed, the project is scheduled, and the team is assembled before the estimate is prepared.

Eight Payment Strategies

Designers can be compensated for their work by way of a variety of payment methods. Clients and designers should negotiate a payment strategy that meets both of their needs. Here are some interesting options:

1. Fixed Fee

Agree to a total fee for the project. Invoice 50 percent before work begins and 50 percent upon completion. Bill expenses at the end of the project. This is a good strategy for smaller projects with clear deliverables.

2. Progress Payment

A project is broken down into sequential phases of work, with the fees and, possibly, expenses invoiced at the completion of each phase. Related to this is dividing an agreed-upon project fee into monthly installments. These progress payments are based on the calendar, and not the work completed, as is the case with the phased approach.

3. Modular

Divide a large project into smaller modules of work and bill them as separate jobs. This works well for related but not sequential work. For example, design a company’s corporate identity in January, and then do the website in June.

4. Retainer

In this ongoing designer–client relationship, the designer agrees to a fixed fee, typically invoiced monthly, for a specific amount of work. This strategy is good for ongoing publications or clearly defined repetitive tasks—for example, developing a new top page for a website every week.

5. Hourly

In this open-ended agreement, the client pays the designer a fixed hourly rate for every hour worked on a project. Good recordkeeping is essential here. Some clients ask for a not-to-exceed ceiling on hours prior to commencement of work to stay within a certain budget.

6. Deferred

The designer and client negotiate a fee, but payment is deferred until a mutually agreed-upon date. This is somewhat risky for the designer, but good for a client with a startup business. Perhaps the fee negotiated is slightly higher than normal to offset the risk.

The designer agrees to be paid a certain fee, typically lower than his or her standard practice, but in addition receives profit participation in the client’s business. This ties design effectiveness to sales and business results and is another good strategy for startup clients or new products the designer is intricately involved in creating.

8. Trade

The designer is paid in-kind with client services or products instead of with money. Such barter agreements work if a clear value for the designer’s work is established. Make sure the design is traded for the wholesale (not retail) value of the client’s service or product.

Rights and Compensation

One thing designers must consider in terms of money and design is ownership of the work being created. Who owns what, and how the work may or may not be used, is a negotiating point that also has financial implications. This concept is tied to the designer’s intellectual property rights and the client’s right to use the work they commissioned the designer to create.

Intellectual property

Intellectual property (a legal reference to the creations of the mind: inventions, literary and artistic works, etc.) is debated by lawyers worldwide. In the United States and Canada, for example, all creative work is owned by its creator until the creator transfers ownership in writing to someone else. This is the cornerstone of copyright protection (legal protection that gives the creator of an original work exclusive rights to use that work within a certain period). Other countries may take different views and have different laws, so designers must understand what is true and legal in the country in which they practice design.

There are some complex rights and usage agreements that can affect a graphic designer. For example, in the United States many clients require designers to work under a work-for-hire contract, which is a written (not verbal) legal agreement between the designer and client stating that the client owns all work developed by the designer under the contract. In essence, it legally makes the client the creator of the work and affords them all the related rights of a creator. This isn’t a bad thing, but it means the client is now undisputedly the owner of the work. As such, a designer might want additional compensation.

It is important that the designer and client know who owns the work and how it may be used. For example, when a client owns outright an illustration that a designer developed for a pamphlet, the client can use that image in any future advertisement or on their web page, without paying the designer anything additional. Therefore, a designer would want to charge more for this kind of complete transfer of rights and ownership. Alternatively, it could be a negotiating point: Charge a lower fee, but the client has restricted usage rights for the work.

Compensation and the notion of intellectual property is a good topic for a designer to discuss with an attorney. You can also seek information from various design organizations, and share this information with your peers. Know your rights, know your client’s needs, and know the laws at the intersection of these two things.

Factors to consider when thinking about the material worth of usage rights and your corresponding fee for a design include

• The value placed on similar work (perhaps even for other clients)

• The category or media in which the work will be used

• The geographic location or area of distribution for the work

• How the client will use the work (for what purpose)

• How long the work will be used

• How many items will be produced that incorporate the work

Licensing Options

Most of the work graphic designers do will be commissioned by a client for a mutually agreed upon sum or fixed project fee. However, some designers license their work to clients instead. Licensing means allowing or granting use of an original work for varied compensation based on the license. Usually, licensing takes one of these two forms in design:

Use-based Licensing

The designer’s compensation is based on how the work is used.

• This often occurs for images such as illustration and photography.

• It’s frequently negotiated for publications, print or digital.

• Additional uses, or changes in use, require additional agreements and compensation to the designer.

• Payment by the licensee (client) is typically made to the licensor (designer) before the work is used.

The designer’s compensation is a royalty or a percentage of the money received from the net sales of a product that incorporates the designer’s work.

• This often occurs for merchandise for sale.

• It’s frequently negotiated by product designers.

• Compensation is tied to sales and the public’s acceptance of the product.

• The licensee (client) must allow the licensor (designer) to review accounting/product sales records.

• Payments typically are made quarterly, but can be negotiated otherwise.

• An advance on royalties is a payment the licensee (client) makes to the licensor (designer) upfront that is then deducted from the royalties to be paid in the future.

Even if you do not choose to be paid under a licensing agreement, your subcontractors may prefer to be paid this way. For example, it is common for an illustrator to allow his or her work to be utilized through a use-based licensing agreement.