122

7 Sensing and Sensemaking

To have, without possessing

do without claiming,

lead without controlling:

this is mysterious power.

—Lao Tzu, Tao Te Ching

I’m particularly impressed with the power of small-group workshops to kindle creative thought. This chapter shows how to use workshops to draw out insight from foresight.

Stories and immersive experiences are very useful for leaders, but you still need to draw your own conclusions and create your own strategy if you are going to get there early and compete. Both sensing and sensemaking skills are needed. First, you sense what’s going on around you and what might be possible in the future. Then, you need to make sense of it all.

Sensing is basic to the “mysterious power” of leadership and the ability to “lead without controlling.” Do you sense accurately what’s going on around you? Are you sensitive to the right issues at the right time? Are you overly sensitive at the wrong times? Do you have good business sense? Do you have common sense? Are you sensible in your decisions? Are older workers sensitive to the wants, needs, abilities, and limitations of younger workers—and vice versa? Those who get there early are sensory wizards who are attuned to what is going on around them. Sensory skills and intuition are linked in most effective leaders.

Wayne Sensor is CEO of Alegent Health, a progressive health care provider based in Omaha, Nebraska. The first time Wayne came to Institute for the Future, I met him in our lobby and blurted out spontaneously: “Sensor! What a great name for a leader!” After trying unsuccessfully to hire him (we’d love to have someone at the Institute for the Future named Sensor), I kept thinking back to that day and to Wayne’s wonderful leadership name: Sensor.

123

Leaders sense the future, drawing out insights and acting with informed sensibility. Leaders develop their own ways to sense dilemmas, engage with them, and develop flexible responses. Leaders also teach others about sensing. For example, how might older workers mentor next-generation leaders, and vice versa? Who teaches whom, in which situations? The art of sensing is fluid, like the martial arts.

Sensing and sensemaking are basic to innovative strategy. This centrality is because innovation is about conceptualizing and bringing new things into the world, a fundamentally creative endeavor that requires sensing, sensitivity, and common sense. Innovation requires a combined familiarity with analysis and intuition. Being able to identify what’s most important or influential requires an ability to sense and make sense of both concrete information and qualitative experience. Fortunately, there is a multigenerational leadership sensibility starting to emerge in the midst of the dilemmas all around us. The mix of generations in the workplace can be a major resource if organizations can figure out how to leverage the strengths and minimize the weaknesses of each cohort. Workshops are a good way to pull together these diverse points of view.

Think of sensing as listening: listening to the world around you, listening to the signals you think are important for your organization, and listening for your inner voice of innovation. Sensing is listening for the future, hearing something that others don’t yet hear.

FORESIGHT TO INSIGHT TO ACTION WORKSHOPS

Moving from foresight to insight is an intuitive search for “Aha!” It is a search for coherence in the midst of confusion. It is a nonlinear creative process best done in a small-workshop setting. What new strategy might be created—given the external future forces that are at play?

124

For somewhat mysterious reasons, small groups are particularly good at listening for the future in creative ways to generate insights and seed innovation. In an interactive workshop setting, a group of seven to twenty-five people can be amazingly productive—if they can learn to engage constructively with one another. My ideal Foresight to Insight to Action Workshop involves about twenty smart and engaging people from varied generations and backgrounds.

When planning a Foresight to Insight to Action Workshop, you need to do some assessment of where you’d like to focus. In our work with top executives, a typical workshop will have the following emphasis: 40 percent on foresight that is provocative for this particular organization, 40 percent on possible insight provoked by the foresight, and 20 percent on possible actions. This distribution can change, however, depending on why you are using the cycle and the organizational challenges that your organization is facing.

We worked with the president of a global business, for example, who set the distribution at 20 percent foresight, 40 percent insights for their business, and 40 percent on action steps, including a very specific discussion of who would do which tasks by when. With this guidance, we sent the forecast out in advance and designed a group process that emphasized a to-do list and schedule at the end. The Foresight to Insight to Action Cycle is inspired by foresight, so it is critical that a future view be included in some way, even if it is a very pragmatic way. However, the cycle can be adapted for action-oriented situations where you just don’t have time for much foresight and have to act quickly.

Foresight to Insight to Action Workshops work best when they have the following ingredients:

- A meeting owner. Having a single person designated as a “meeting owner” gives focus to the workshop, provides a sense of urgency, and makes it more likely that the results will be used in practical ways. Even having a discussion about who the meeting owner is can be useful. The content facilitator works closely with the meeting owner to plan the process flow for the Foresight to Insight to Action Workshop. The meeting owner may need to make real-time decisions during the workshop regarding next steps. Of course, ownership can change—sometimes abruptly. I was once leading a workshop with the executives of a large retailer on the edge of bankruptcy. Our workshop was on the retail store of the future, thinking ten years ahead. Halfway into the one-day workshop, the newly appointed CEO (a turnaround artist) turned up by surprise at our workshop. I called a break to meet him, and when we returned, he became the new meeting owner. At his instruction, we shifted our sights from ten years out to three months out. What was a foresight meeting became an action meeting, in the face of survival and the presence of a new leader. The foresight was provocative, but the emphasis was on action and who would do what by when. The company’s turnaround literally began in our futures workshop.

125

- A target outcome. It is relatively easy to have an exciting conversation about the future, but it is very challenging to pull the threads together and make the conversation practical for the present. Having a clear outcome, a mantra for the meeting, gives everyone focus. I did a workshop in which our outcome goal was to reduce a large number of alternatives down to five priorities for action. We worked for most of the day on this task and were nearing our goal. About an hour before the scheduled end of the workshop, one of the meeting planners suggested that we change our outcome goal and widen the number of alternatives we would accept. At this point, in front of the group, I turned to the meeting owner and told her our alternatives—so that all would see her choice. If we opened up the discussion of alternatives, we would not meet our original outcome goal by the end of the workshop. She made the call to stick with the original outcome goal and keep rolling. (Sometimes it may be best to call a break and have this conversation with the meeting owner privately, but other times it is important for the whole group to see the options and understand the choice.) The Iraq Study Group, which finished its report in late 2006, concluded with seventy-nine recommendations. As I facilitator, I think seventy-nine is way too many outcomes. Action-oriented strategic workshops need to focus their recommendations to not more than about five priorities. Seventy-nine recommendations may be a success in terms of consensus, because everyone agrees with at least some of them, but I view it as a failure in strategic convergence. As a facilitator, I’d be embarrassed to end a workshop—let alone an eight-month study group—with that many recommendations.

126

- A diverse group. Small-group conversations can be great, since people with different perspectives can stimulate one another’s thoughts and draw links that are not apparent. Expertise is important, but the definition of expert needs to be considered carefully. Outside-in views are usually important, but it is also important to have key inside players who will own the outcomes and help bring them to action. Of course, diversity can create tensions that can be both positive and negative. Basically, you need diverse people who will play well together. Generational mixes and mixes of thought styles are particularly helpful. As a content facilitator I try to study the backgrounds of all the workshop participants in advance. If I know there are people who may be difficult in the workshop (that is, not play well with others), I try to meet them in advance and get a better sense of their views and style. You want to create a mood of high conflict around ideas but maintain respectful behavior toward others. Holding this balance can be delicate, particularly in high-powered groups with individuals who are under great pressure.

- A content facilitator. It helps to have a content facilitator leading a Foresight to Insight to Action Workshop to assist participants in drawing the links between the foresights, insights, and possible actions. By content facilitator, I mean someone with both content and group process skills—and with the instincts to be able to decide when to play which card. A good content facilitator should know at least enough about the content of the forecast being used to present it in a provocative way and then facilitate a conversation to identify insights—given the foresight—and then cluster and prioritize them. The content facilitator should be friendly but firm, a kind of pace car for the conversation. He or she is the real-time weaver of ideas and of people in conversation.

- A chunk of provocative foresight. A big-picture forecast, such as the Forecast Map inside the book jacket or the text summary in Chapter 2, can be a wonderful stimulant for a Foresight to Insight to Action Workshop, but it is also important to think through the message track that you want to use to stimulate the discussion. Foresight is based on outside sensing and an integration of facts, observations, and possibilities, which should be presented in a crisp and provocative form that engages the group without overwhelming the participants. A content facilitator must become skilled at folding foresight into the conversations that occur during the workshop. The Forecast Map inside the book jacket contains a number of hot zones, which are intersections of driving forces and impact areas. The content facilitator needs to be good at telling provocative stories at these intersections, to stimulate conversation about insights and possible actions. It is best if the foresight gets folded into the conversation throughout the workshop, not just in a big chunk at the start. Artifacts and scenarios can also be used as chunks of foresight, mixed in with the conversation to keep the insights and possible actions coming.

127

Each participant should feel slight off balance in a Foresight to Insight Workshop, never knowing when he or she might be called upon. The mood should be relaxed but charged with energy.

I recommend taking a substantial block of time for introductions, since they allow everyone to become oriented to the workshop and build trust with one another right away. I’ve also learned through doing many of these workshops that it is very important for all participants to get individual airtime early. The longer it takes for a senior person to say something in a workshop, the more likely it is that when he or she does say something, it will be dysfunctional. If you give everyone space and a voice early, the chances for great group dynamics go up substantially.

128

I don’t recommend simply going around the room and asking people to introduce themselves without any guidance. Rather, I think that a good content facilitator should move with an asymmetrical pattern and draw people out in introductions. What is the voice that each participant will be taking? The future will be asymmetrical, so why go around the room in a symmetrical way?

Introductions are not a preamble to the workshop; they are an important part of the workshop and a great opportunity for early engagement. A good content facilitator will be able to weave content from the forecast into the introductions, in dialogue with the background and interests of the participants.

The best workshops have a feeling of being at the edge, with a touch of urgency, punctuated by episodes of reflection. If there is no external source of urgency (hard to believe in these times), the content facilitator needs to create a sense of urgency. For example, I often facilitate with my colleague Susannah Kirsch, and we will sometimes switch roles every hour or so, with the timing paced by a countdown timer. Each time block has a goal of an aggressive outcome, with a handoff to the next time block. The goal is to stretch, with the countdown timer as a discipline and motivator. We strive for a sense of positive pressure to perform as a team.

When I co-lead Foresight to Insight to Action Workshops with Mark Schar, a former P&G executive and former chief marketing officer (CMO) for Intuit, I stand in the front of the room, and Mark stands at the back. I am the workshop leader, and I stay focused on foresight. Mark is a “color comments guy” who becomes the voice of insight and practical actions that are provoked by the discussion. Mark stays in tension with me throughout the workshop: the tension is between foresight and action. This front-back dynamic creates a different kind of energy in the room and keeps the participants spinning around the cycle from foresight to insight to action.

As forecasters—since nobody can fully know the future—we are always at the edge of our expertise. For workshop participants, we want people who get more comfortable as they get to the edge of their own expertise. This, of course, is not true of most people with graduate degrees— who tend to get more comfortable in the center of their expertise. We look for people who “fail gracefully” at the edge of their expertise. Said another way, we look for people who can contribute usefully to a dialogue even if they don’t know what they are talking about. And, of course, we don’t want people who pretend that they know what they are talking about when they do not.

129

How can someone contribute usefully if they don’t know what they are talking about? First and foremost, they can ask good questions— which are usually much more useful than answers when it comes to a forecast since nobody can know the answer. Second, they can use models or frameworks to explore what is known and what is not known. The content facilitator is the guide as the workshop participants navigate the uncertain space stimulated by the forecast.

Venue and mood of the room are also important. For example, we once held an exploratory innovation meeting for a group of technology and human resources executives at the Explorer’s Club in New York City, a membership club where only the world’s leading explorers can join. For another workshop of technology executives interested in innovation, we chose the luxury box of a NASCAR raceway, with meetings in the pit area about technical innovation in NASCAR racing. In another case, we held a thought leaders workshop in the press box of a new football stadium. The point is to use your venue as part of your content, to help explore an aspect of the future with which you are engaging. The venue can be an immersive learning experience in itself or at least can be interesting and provocative. You can also bring the mood to your room with artifacts that reflect the topic you are exploring. For example, with brand-building workshops we will often have posters, videos, and other brand artifacts all around the meeting room in order to get the participants in the mood to be creative around brands. The quality of your room experience will have an impact on the quality of your outcomes, for better or for worse.

In our Foresight to Insight Workshops, we often use a graphic artist to record the insights and create a group memory in graphic form. The idea is to allow the workshop participants to think creatively, without having to focus on note taking. The artist creates a collage of key phrases and evocative images while the content facilitator uses the foresight to stimulate discussion, and works with the group to hone and cluster the insights to get them to an appropriate level of specificity—given the goals of the workshop.

130

7.1 Graphic Recording Captures Insights and Group Memory(Source: Anthony Weeks, 2006)

131

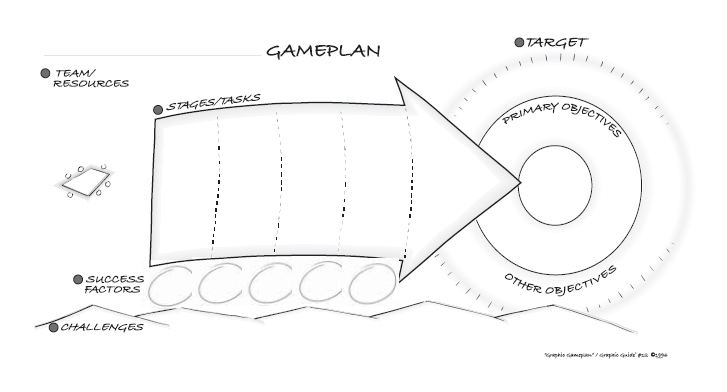

7.2 Group Game Plan by Grove Consultants International

I have worked with Anthony Weeks in many workshops, and I include an example of his work here (see Figure 7.1). Anthony created this graphic on a four-foot by eight-foot sheet of paper in real time, as the group talked. Group graphic recording is an unusual art form, and Anthony is one of the best. He is able to almost channel the conversation of the group, in a deep state of concentration, and then create a visual summary that is memorable for everyone who was there.

Once a level of specificity has been set (usually through one or two illustrative models of the types of insights that the group is seeking), then the artist can array the options in a way that they can be prioritized by the group. The graphic template in Figure 7.2 was developed by David Sibbet to help groups agree on a plan of action.1 It is most useful at the insight to action stage of a workshop.

Sometimes we use electronic polling to do the prioritizing, but usually colored dots are more effective. (When we use the dots, participants are given equal numbers of dots and are asked to “vote” by placing the dots on the graphic display.) This process of sifting, grouping, synthesizing, and evaluating is very important to sort out what is possible and to begin to think through the virtues and constraints of the various possibilities. Typically, a Foresight to Insight to Action Workshop is not focused on deep consensus or decision making. Rather, the focus is on generating possible insights and beginning to prioritize them. Full evaluation of the insights typically comes later, with a smaller leadership group.

132

The facilitator needs to keep the group focused on possible insights or action steps that are stimulated by a particular forecast. There is a temptation within many groups to argue with the forecast, rather than accepting it as one possible future and drawing out insights or actions if this particular future should occur. Fortunately, you don’t have to agree with a forecast to find it useful. It is most productive for a group to assume a particular forecast could occur (assuming it is plausible and internally consistent) and use it to stimulate insights. Then if you want to try another forecast, go back through the cycle again. This is where scenario development can come in to create a range of forecasts. Arguing with a forecast is always possible, but it is usually not very productive in providing input to strategy. It is much more valuable to go through the Foresight to Insight to Action Cycle first and then do another forecast if you question the value of the first one. Trusting the forecast usually leads to much better outcomes. Even if a forecast does not accurately predict what happens in the real world, it can still be useful to provoke insights. The ultimate criterion for a successful forecast is whether it helps people make better decisions.

A successful workshop depends on a good start, with prepared minds. Preparing your mind means asking questions like these:

- What are the current pain points for leaders and others in your organization? What pains keep your leaders awake at night? Although major change is occasionally prompted by compelling vision, change is more commonly prompted by pain. If you understand the current pains of an organization, you can figure out what kinds of foresight could be most provocative in generating pain relief. Typically, people and organizations are not motivated to change when things are going well.

- What is the intent of your leadership? If intentions are understood, then foresight becomes context around your intentions. Foresight is focused on external future forces. Intent always lives in a larger context, and foresight can help you understand—and possibly influence—that context. For Martin Luther King, the vision was the Promised Land, and his intentions focused on nonviolent direct action to get there. The intentions of leaders must be very clear, although leaders need agility to figure out on the fly how that intent can be achieved in the field.

- What is the destination of your organization? One of our clients did a ten-year vision of where the company wanted to be as a brand. The leadership team did a destination statement, refined the statement, and shared it widely as a target destination. Once the destination was clear and accepted, they used foresight to identify external future forces that either helped or hindered the steps toward their target destination. What are the waves of change that you could ride to reach that destination? What are the waves of change that could drive you off course?

- What is the biggest business challenge you are facing right now? How might that challenge be informed or influenced by external future forces?

- What outside forces are likely to influence you? What’s going on in the lives of the participants, outside this meeting? Beware of people, including yourself, who may bring views to a meeting that don’t belong there. Sometimes outside forces will influence a meeting, even if they have nothing to do with the content of a meeting. Foresight encourages people to step outside their normal routines, but the day-to-day pressures of life can still bleed in.

133

For a successful workshop you can also follow some of the tips and techniques that we have learned from doing Foresight to Insight to Action Workshops:

134

| Introductions for a familiar group, where most people know one another. | Routine introductions can be short, but establishing a voice for each participant is important. For example, “Tell us something that your colleagues will not know about you.” |

| Introductions for an unfamiliar group, where most people don’t know one another. | Introductions should be longer in order to engage the group. Keep the introductions personal and draw links to content when appropriate. |

| Presentations where there is a lot of complex material that is new to participants. | Allow for very brief presentations to share material, and for discussion so people can ask clarifying questions and make links to their own work situations (individual learning), or to the situation or challenge under discussion (group learning). |

| Explore possibilities or stories, leveraging the group’s experience to do so. | Use small-group work for scenario creation activities. Provide clear guidelines and in some cases an example to stimulate people’s thinking. Imaginative activities are usually most effective when people have had an opportunity to review new material before being asked to create scenarios or stories. |

| Focus on individual learning, rather than group decision making. | Provide tools such as learning journals and time to allow people to gather their thoughts. Allow time for individuals to work on their own to develop their ideas, and use smallgroup discussions and sharing to enable people to learn from one another. |

| Focus on group learning and decision making. | Use the time to go back and forth between sharing information and both large- and small-group discussion. When you break into small groups, allow time for reporting and discussion that builds on the ideas developed in the small-group setting. Small groups can leverage the diversity of expertise in the room to dig deeper into specific topics. |

| Focus on experience based learning. | Use group immersive experiences with time to debrief and share the lessons. For example, consumer home visits or shop-alongs can be used to explore new product possibilities. |

| Prioritizing insights or agreeing on action steps. | Include dot voting on ideas or strategies once they are presented and discussed, and include both smalland large-group discussion to build shared understanding and consensus. Small groups can be effective at advancing complex ideas, particularly when you have a lot of material to cover. |

| Generating new insights or possible action steps. | Divide people up in small groups to maximize creativity. Use the largegroup work to share new ideas and explore critical questions. If needed, use the large group to stimulate new discussion. |

| Going for actions, with signups regarding who will do what by when. | If participants are to be responsible for making sure the work gets done, use part of your session to sign people up for next steps. Encourage your outcome owner to have a list of people he or she believes could successfully implement any actions you agree to take. |

136

During these workshops, there will be moments of intense conversational flow and moments of silence, when the conversation stops. Silence allows time for reflection, and a good facilitator will allow the silence to happen to allow participants to use the time to think more deeply. Conversational bursts are also important, since they can provide a new zone of creativity for a group to go places that the individuals cannot. The danger of constant conversation is that some important voices may not be heard because they are overwhelmed by their more vocal colleagues. The challenge is this: how long do you hold the silence as the participants process the complexity and try to make sense out of it? When do you interrupt an active conversation to do a process check, to refocus, or to allow the quieter participants to jump in? Content facilitators or meeting owners need to sense the group and make the call.

In any workshop conversation, leaders need to sort out what’s important from what’s just new. As I mentioned before, if a topic is really important, it is probably not really new. In the age of the Internet, everybody has access to what’s new. The critical task now is to be able to sort through the newness and decide what’s really important. When is the timing likely to be right? Many important innovations take years to emerge, usually in fits and starts and after many failures. Few successful innovations are truly new at the time they happen. Most are reimagined versions of an earlier effort that failed.

USE POWERPOINT FOR PROVOCATION

Brief, provocative PowerPoint images can draw groups into a conversation. In a Foresight to Insight to Action Workshop format like the one we are discussing here, however, PowerPoint can be a detriment if it is not used well.

First, the use of PowerPoint in a workshop room requires that you arrange the room so that it faces the projection screen. This arrangement takes the focus off the group and puts it on the PowerPoint slides. Having a PowerPoint screen involves a major tradeoff in small-group dynamics: people tend to look at the screen instead of looking at one another. The process of drawing out insights stimulated by foresight requires the participants to engage with one another as a group.

137

Presentations should be used for provocation only and should not look too finished. Consider this story from my experience:

In the 1980s, I helped to organize an industry workshop in Hakone, Japan. We brought together several hundred leaders from around the world, all of whom were major players in an emerging marketplace. The purpose was to share foresight about the emerging industry and draw out insights about how the various companies could collaborate to encourage growth in the field.

Apple Computer was the host, and the company had advanced presentation capabilities. At the time of this workshop, most of the participants were used to seeing 35 mm slides for formal presentations and overheads for less formal ones.

At the conference in Hakone, we did parallel workshop sessions with the participants on into the night, drawing on the many resources that were present to create a draft plan regarding how to grow this emerging market quickly. Those of us organizing and facilitating the conference met together to synthesize the workshop findings and get them ready to share with the large group the next morning.

At about 4 a.m., we shared the synthesized results—which were very impressive—with the top Apple executive who was present. He loved the conclusions and agreed to present them to the large group the next morning. Then came a serious mistake.

We debated how to share the draft conclusions. We had a good artist present, and one idea was to do a graphic summary of the evening’s work and display it for the group. The hand-drawn feel, we thought, would be engaging for the audience as they considered the small-group insights and started to move toward possible action steps.

The Apple executive, however, was anxious to show off Apple’s new capabilities to do high-quality presentations quickly. He made the call that we would present the workshop insights in a presentation format that would demonstrate Apple’s presentation and artistic capabilities. Everyone would be amazed that Apple had done such a high-quality job so quickly, he thought.

Well, he was right that everyone was amazed. It was a beautiful presentation, and the Apple software and hardware performed with precision. The presentation was so amazing that many of the participants concluded immediately (though incorrectly) that Apple had prepared this presentation in advance.

Essentially, the presentation looked too good and too finished. Rather than drawing the conference participants into a conversation that reflected the small-group insights and beginning a synthesis process, the presentation planted seeds of distrust regarding Apple’s intent.

We worked through these reactions and eventually made good progress going forward from the conference, but I took away a major lesson: any presentations, especially to a group engaged in a foresight-to-insight discussion, should not appear too finished. Presentations should be good enough to reflect the quality of early provocative thought, but not so finished looking that people feel they are being sold something. The presentation medium communicates something that is just as important as the content.

Imagine a world in which your PowerPoint library is organized like the playlists on your iPod. The basic unit of organization is not the linear presentation but the knowledge nuggets that are embodied in a particular image or video and captured in a PowerPoint slide. With a PowerPoint playlist, a workshop organizer can call up images spontaneously during a Foresight to Insight to Action Workshop, to provoke thought. We need to get beyond thinking of PowerPoint as a linear medium to replicate what we used to do. PowerPoint is designed as a linear medium, unfortunately, but there is great potential for it to evolve into a medium as flexible as an iPod, one that encourages users to think of their knowledge in terms of key ideas that can be rearranged as needed.

I compare PowerPoint use to drinking wine. Drinking wine in moderation is great; it is even healthy for you. If you overuse wine, however, you become an alcoholic. Similarly, if you use PowerPoint intelligently in moderation, it can be healthy for your meetings. It is not that PowerPoint is bad per se but rather that, like wine, it can be so easily abused. Many people in organizations behave as if they are addicted to Power- Point, yet—like many alcoholics—they don’t realize their addiction. The ease of PowerPoint slide creation subtly encourages sloppiness in thought that makes it harder to draw out insight.

139

The best PowerPoint presentation that I’ve ever seen is the one the Al Gore gives to discuss global warming, the presentation that is at the core of the movie Inconvenient Truth. Gore uses PowerPoint in a dramatic and yet human way to help audiences visualize complex data in support of a specific conclusion. This presentation by Al Gore may be the world’s best PowerPoint presentation, but it is intended for large groups—not small-group workshops. A few of those images, however, could be used very effectively to provoke a foresight to insight to action conversation.

In this chapter we’ve seen how sensing and sensemaking are needed to bring together foresight and insight in a workshop setting. Chapter 8, about the transition from insight to action, provides specific examples of how foresight has provoked insight that led to inspired strategy.