24

2 Institute for the Future’s Ten-Year Forecast

The future is a life seen through the lens of possibility.

—Kathi Vian, IFTF’s Ten-Year Forecast Leader

Chapter 2 draws from Institute for the Future’s ongoing forecasts of the global business environment, information technology horizons, organizational shifts, and health trends to provide a base forecast for this book, a way to hold the complexity of this decade of dilemmas in your mind.

Our forecast is a plausible and internally consistent view of future forces affecting the global environment, thinking ten years ahead. What are the external forces that will shape the next ten years, with an emphasis on dilemmas that are important for leaders to consider? Our forecast visualizes a future: the global social and technological context within which leaders, workers, and organizations will be living ten years from now.

Any map, of course, is not the territory. A map is a representation of reality, but it is not reality. In fact, nobody really knows the reality of the future; we are all running on approximations, some better than others. The next decade is likely to be characterized by extreme dilemmas and bewildering twists in logic, so forecasting is especially difficult.

25

The external future forces that will be presented in this chapter invite, and perhaps require, a sense of urgency. In order to respond to the challenges of the future, we need to reflect, tune, and design a flexible approach to leadership—which is what this book is all about.

DIRECTIONS OF CHANGE

Before discussing the Forecast Map, it is important to highlight the underlying directions of change behind the forecast. Think of these directions as historical context for the future that is to follow. The directions of change presage a forecast. In our forecasting at IFTF, we have learned that—even in highly uncertain times—you can still get a pretty good sense of the direction of change, even if the particulars are blurred. We are looking here for waves of change. Once the waves are apparent, you may try to ride them or not, but at least you can avoid getting hit by them.

The following statements indicate direction, not destination; we are moving in the direction indicated, but we may never actually get to the end point toward which we are moving.

MOVING TOWARD everyday awareness of vulnerability and risk—in both the developed and developing worlds. The often competing forces of extreme polarization and new abilities to cooperate characterize this shift. The next ten years will be extremely challenging, and they will feel that way to almost everyone. This kind of world already exists in many parts of the developing world, but the developed world will also experience a dramatic increase in anxiety and sense of risk. The day-to-day personal preparedness disciplines in hot-spot cities like Jerusalem are likely to spread across the developed world as concern over security increases.

MOVING TOWARD an hourglass population distribution where old age is the new frontier, but the kids will be heard. The developed world will experience its largest elderly populations ever, while the developing world will be driven by youth. The young “digital natives” are those children of the wealthy world who were born into and unconsciously bred for the emerging world of dilemmas and global connectivity.

26

MOVING TOWARD deep diversity that is “beyond ethnicity,”1 in the workplace and in society. Diversity is a dilemma in itself, and it presents major challenges as well as exciting opportunities for innovation. Diversity is essential to creativity.

MOVING TOWARD bottom-up everything, where people interact with the products and services they consume. New types of loosely connected teams will become the new basic organizational unit for innovation. The grassroots economy, which has deep roots, will be amplified and multiplied by new media networks, games, and hobbies. Hierarchies will be important in some cases, but they will come and go in much more fluid ways.

MOVING TOWARD continuous connectivity where network connections are always on. Online identities will become increasingly important as people learn to express themselves—and leaders learn to exert leadership— in new ways that are consistent with the new media but are still linked to the old media.

MOVING TOWARD a booming health economy in which health is an important filter for many purchasing decisions—and health risks are on everyone’s mind. Health values will be central as consumers become more health conscious while also pursuing indulgent options in this both/and world.

MOVING TOWARD mainstream business strategy that includes environmental stewardship combined with profitability—doing good while doing well. Environmental practices and sustainability strategies will become increasingly common and increasingly urgent. Science—particularly the life sciences—will become increasingly important, both as a source of risk and as a way of improving the world around us.

27

A GUIDE TO THE FORECAST MAP

The Forecast Map inside the book jacket is a matrix-style map, with five driving forces and four impact areas. The map pulls together the core elements of our Ten-Year Forecast, with an emphasis on those future forces that will affect leaders. This map makes it is possible to hold a complex array of interacting future forces in your mind all at once. Please find the Forecast Map on the inside of the book jacket and open it in front of you as you read this chapter.

Expect to be a bit overwhelmed by this map when you first see it. The future is extremely complicated, but this map will help you grasp what’s going on.

Each row is a Driving Force that summarizes visually a forecast storyline as you read across. Each column is an Impact Area: People, Practices, Markets, and Places. For each storyline, I suggest below a core dilemma for leaders and organizations. To the far right of the Forecast Map, you’ll find what we call an “artifact from the future.” Artifacts from the future combine scenario-creation skills with those of design prototyping. This chapter is a text description of the visual map inside the book jacket.

Storyline 1: Personal Empowerment

The word consumer is obsolete, but there is no better word to replace it yet. The word consume means to destroy. But consumers are not just destroyers or just passive recipients of mass messages, and increasingly people resent being treated as such. Consumers are empowered people whose powers are amplified by the interactive media that they are rapidly learning how to use.

For very large organizations, this personal empowerment creates a dilemma: how can they engage constructively with the increasingly powerful individual people, and networks of people, who buy their products and services?

Beginning about ten years ago, we introduced into IFTF forecasts the concept of the new consumer to describe the upscale, educated, innovative people who created new market demand and shaped the mix of products and services. About five years ago we noticed that the new consumer was not just upscale and not just educated in the formal sense: more or less everyone was becoming part of the mix of engaged and empowered people. IFTF’s research suggests that engaged consumers are characterized by three bellwether behaviors:

- Self-agency: acting with independence, on one’s own behalf, but with close networked links to others, so that individual decisions are magnified but influenced by others.

- Self-customization: adapting and applying core products or services to their own individual needs, with the expectation that products will be customizable to their needs.

- Self-organization: organizing responses and initiatives in ways that are difficult to anticipate.

28

Engaged consumers are a force to be reckoned with. Engaged consumers can inject a brand with incredible buzz, as did the early iPod users. Apple got there early with a well-designed and compelling product that was promoted mostly by word of mouth, although Apple fueled the fire.

Engaged employees have the same kinds of power, but their power is applied to work. Indeed, many practices of work (for example, time and task management) are being brought home, but influence goes back and forth between home and work as distinctions between work and private life become blurred. An IFTF forecast for a professional services firm, for example, suggested that such work/life crossovers are causing jobs and hobbies to mix, creating “jobbies.” Engaged workers looking for self-expression bring their hobbies to work, or their work to their hobbies. Some will seek second or third careers to more fully express their jobby interests.

As I have worked with corporations, I’ve found it very useful to ask employees about personal hobbies, not just about work. In my experience, some corporate cultures tend to drive people toward exotic hobbies that more fully express their personal identity. If an engaged employee’s job does not allow for full expression, the employee will likely be attracted to hobbies that do. The ideal job is one that combines job and hobby, so that the employee will have passionate interest but the results will make useful contributions to the business. Empowered workers seek more flexibility, they want to make a difference, and they have a strong sense of the importance of their own private life.

29

People are shifting their identities from consumption to creation— including customization and do-it-yourself (DIY). People are adopting tools and organizational practices that foster both self-expression and collaboration. This shift implies a move toward more open economic exchange, with an emphasis on external innovation. A key example is the increase in open-source technology, although different places have different levels of openness. Software in Silicon Valley, for example, is obviously trending toward open source, and in London is also becoming more open source but less so than Silicon Valley.

Personal empowerment will be shaped by the aging baby boomers. First, the aging baby boomer generation has changed every major institution it has come into contact with, and the concept of retirement looks likely to be next on the list. I expect that the word retirement will disappear altogether and be replaced by a baby-boomer-type term like redirection, regeneration, or refirement. Second, we will see increased longevity in this generation, with a possible shift in retirement age, since government retirement benefits promises are becoming harder and harder to keep. Peter Drucker pointed out that the retirement age in the United States was established in the 1930s during a period of employment surplus, when legislators wanted to clear out room in the workforce for young workers. Meanwhile, since the1930s health care has improved greatly, and most jobs involve much less physical strain. Drucker suggested that if all the changes were taken into account, the retirement age in the United States ought to be about seventy-nine, rather than sixty-five. Such a proposal would not be popular with many people, of course, but Drucker was definitely on the right track.2

The new retirement will include new forms of empowered work and leisure, new combinations of work and hobbies. The boomers will rethink and reform the notion of careers for fifty-plus in several key ways:

- Working older: don’t expect the boomers to stop working, unless they get bored.

- More health expenses and investments in health: chronic disease meets longer life.

- Lower levels of government support: Social Security will not be enough.

- Expanding, not narrowing, horizons: the empowered boomers have a big-picture view, so they will continue to reach out and grow.

30

Meanwhile, labor shortages will create market forces around empowered workers. Most of the labor shortage will be in the knowledge industry, and many companies are exploring ways to connect virtually with educated labor pools in India and other parts of the developing world. Immigrants are likely to fill in any blue-collar shortages, although the politics of immigration will be volatile.

Employers will transition to a more peoplecentric office to promote communication, engagement, and community among its workers. The challenge is to do this for a labor force—from incoming “digital natives” to returning senior alumni—with increasingly diverse needs, expectations, and demands. Think customizable careers, personalized to the special needs of empowered workers.

Increasingly, the old rich and the young poor will bracket the global economy and fuel tensions within it. For those who can afford them, technologies will ease the process of aging.

Workforce diversity will reshape the workplace over the next decade, as the developed world deals with its largest elderly population ever and the developing world offers new pools of young knowledge workers and manufacturing power. The workforce of the future will be shaped by the differing priorities of next-generation workers.

Although most aspects of the future are unpredictable, demographic changes can be foreseen, at least at a general level. Next-generation workers often don’t fit the expectations of today’s leaders. They are not, however, a “problem” that today’s leaders will be able to “solve.” Fortunately, this dilemma of next-generation workers is likely to be more of an opportunity than a risk.

31

Young people have always been different, but the next generation of workers is really different. As this unprecedented future takes shape, an unprecedented new generation of workers is entering the workforce with skills and perspective that their elders do not share or—in some cases—even understand.

Although many high-performing baby boom leaders expect to encounter a stream of problems that they can solve—if only they work hard enough—the next generation of workers won’t have the same set of illusions. (Yes, they will have other illusions.) Younger workers are likely to be more comfortable improvising their way out of dilemmas. Many of today’s kids are already experienced VUCA world players who learned their skills in video gaming worlds that are not as different from business as some may think.

Organizations must prepare for an increasingly heterogeneous workforce in terms of age, nationality, race or ethnicity, and lifestyle. Immigration is changing the ethnic composition of the country, particularly the western and southern regions. Women are having children later in life, and the number of traditional households is declining. Many of the aged will live and work longer, with a strong sense of empowerment.

The first artifact from the future (top at the far right of the Forecast Map) shows how the digital and physical worlds will be blended and used by engaged people. Local information is projected on your eyeglasses as you walk about in a strange city. Jason Tester, who studied human-computer interaction at Stanford and attended the Interaction Design Institute Ivrea in Italy, developed this methodology at IFTF.

Storyline 2: Grassroots Economics

Economies of scale, where bigger is almost always better, are giving way to economies of organization, where you are what you can organize. To get oriented to this still-emerging economic ecology, think of it as eBay on steroids. Everyone can be a seller, and everyone can be a buyer. All organizations—even very large organizations—have the potential to take on a grassroots character. Think personal media, think personalized products and services, and think mass customization or personalization. This economic shift is much larger than eBay per se, but the eBay effect is spreading, setting a tone and breaking new ground. While personalized interfaces are still evolving, the Internet has come a long way already.

32

A grassroots economics dilemma for very large organizations: how to grow financial performance in an economic environment in which scale is a mixed blessing and you must give the feeling of being both large and small simultaneously?

Scale just isn’t what it used to be. It is still important to have scale to reach large audiences, but the scale must be personalized—or at least it must feel personalized to the end consumer. And the scale must be localized—even global brands should feel local, or at least not foreign, and their local value should be apparent. Centralized brute-force scale, where growth is driven from a central core, is giving way to decentralized scale, where growth happens organically at the edges. The “grassroots economy” is a group economy organized for cooperation and mutual gain. Groups create new kinds of economic value, some of which is outside the traditional economy. The second artifact from the future (second from the top at the far right of the Forecast Map) shows how computer parts can be recycled and reused by entrepreneurs in the slums of the developing world.

Grassroots economics is a bottom-up engine of innovation, a powerful world for brands, but a world where brands can be extremely fragile. Engaged consumers can threaten the very existence of a brand, as they did with the Kryptonite bicycle lock when a Web video demonstrated how this supposedly secure lock could be opened with a Bic pen.

Business Week calls it “the power of us.” Howard Rheingold calls it the “sharing economy.”3 New forms of social organization, enabled by connective technologies and increased mobility, will become new sources of value for organizations that know how to tap into them. Workspaces can be designed to maximize the unique role of working side by side to grow relationships and social networks.

As the traditional culture of consumption gives way to more interactive value creation, we will see increases in the technologies of cooperation and the revival of localism through bottom-up processes. Here the counterculture of the 1960s and 1970s has met the technology culture of the 1980s and 1990s, and these two transformational movements will play out on the economic scene as an intensely social, technologically supported grassroots economy comes into its own.

33

Personal media are making it possible to personalize content and experiences. For example, camera phones have created a new medium for self-expression, one that is available anytime and anywhere—by anyone. Amateur photographers now have a medium that they never had before. Web sites such as Flickr and YouTube provide sharing venues, as well as bridges to marketplaces for photos and videos. The grassroots economic driver is moving us toward marketplaces that include both professionals and amateurs, as we are already starting to see in the world of citizen journalism.

Lightweight infrastructure is making it possible to innovate in a more decentralized fashion. In energy, for example, lightweight infrastructure allows power to be decentralized. In telecommunications, cellular telephony and Internet access have made it possible to leapfrog the construction of landline physical infrastructure. Lightweight infrastructures encourage organizations to rethink the movement of goods and services. Central infrastructure will still make sense in some areas (in China, for example, both central and lightweight energy infrastructures are being used in varied settings), but lightweight infrastructures are extending dramatically the range of options for innovation.

Grassroots economics will be enhanced by the geoweb, which is the linking of the virtual with the physical. Alex Pang at IFTF has referred to this as the “end of cyberspace,” since the physical and the virtual will be linked. William Gibson coined the term cyberspace in 1984 to describe the place where we go when we are online.4 In the geoweb, cyberspace is not a separate place where we go, since our physical places are linked to the virtual. Sensors in the physical world provide location and background data to add to our experience in the physical and virtual worlds. During the SARS outbreak in Hong Kong, for example, text messaging services were available to tell subscribers when they were approaching a building where SARS cases had been reported. In the future you will be able to walk beside a river and check the pollutant levels (real-time environmental reporting) or look up the company on the riverbank and check out its credentials—using your choice of filters for the rating—as you walk. Intelligence is becoming increasingly embedded in places and things at the same time—with links to social networks.

34

The distinction between cyberspace and real space is disappearing, but the resulting electronic and physical infrastructure is fueling the growth of grassroots economies. IFTF’s 2006–2016 Ten-Year Forecast puts it this way: “This is the decade in which data, sensors, and semantic processing get imbedded in things, people, and places. This world of smart things will look less like the Jetson world, however, and more like an exquisite dance between groups of people and the spaces they occupy.”5

The Forecast Map summarizes a key historical shift, beginning with the counterculture movement of the 1960s, in which the emphasis was on social transformation. In the 1980s and 1990s the emphasis shifted to technology and network innovation, expressed through the Internet and its many economic impacts. Now the technologies have evolved into media, and the media are becoming the fertile ground for the grassroots economy.

As these economies of connectivity become increasingly visible, innovative businesses will build on that connectivity to create new wealth. The result: commerce will shift by sector and region, with some industries declining while others are injected with new energy.

For example, the grassroots economy allows for the growth of what Chris Anderson calls “long-tail economics.”6 At the end of the current life cycle for many products and services, there are still many people who value the fading product. In fact, the end of the life cycle of a product is sometimes extremely profitable. However, mass-market products cannot focus on niche markets. More customized products and services— and the electronic networks to distribute them—can extract great value from the long tail at the end of a product life cycle.

Networked media, using the geoweb, will make it possible to develop ad hoc infrastructures in areas like security, communications, energy, and waste management. Virtually everything can be “tagged,” which means that an item is marked in a way that can be tracked. Many physical things will have RFID (Radio Frequency Identification) tags, which contain much more information about the item than the current generation of bar codes. As things become tagged, search engines will be there to locate the items and use the information. Although manufacturers and retailers have led the development of RFID up to now, the most transformative applications are likely to be those developed by engaged consumers. Expect grassroots economy efforts to create and program tags for everything from photos and children’s art to antiques and family treasures. With equal effort, engaged consumers will devise ways to subvert and block tags created by others. The third artifact from the future (third from the top at the far right the Forecast Map) suggests how adhesive home RFID tags might be used by consumers.

35

Storyline 3: Smart Networking

We are moving toward a global fishnet of connectivity, with regional talent clusters but uneven technological infrastructure and network practices. In a fishnet of connectivity, smart networkers live at the leading edge of market trends, making distinctive and influential choices about entertainment (which are abundant), health, home, policy issues, and elections. The people who make these choices—the people who use products and services, who participate in nonprofit organizations and government groups, who vote—are not just individuals; they are networks of empowered people. Increasingly, brands are selling not just to an individual; they are selling to a social network.

A smart networking dilemma: how to engage in positive ways with these smart networks and networkers that cannot be controlled and only rarely can be influenced in straightforward ways?

Few hierarchies can match up well with a competing network, except in mature industries or stable zones where change is slow. When your customers and competitors are networks, you need to be a network too. There is a definite shift toward networks within and among large companies.

36

Swarms, or smart mobs as Howard Rheingold calls them,7 are “loosely connected, technology-amplified aggregations of people organizing around fluid topics and incentives” (although many of these aggregations will be dark mobs, or smart mobs with bad intentions). Social software, which is focused on amplifying group capabilities, will allow opportunities to create new social capital. Emergent grassroots economies are making it possible to be more responsive and adaptive on a scale that transcends today’s institutions. In the world of smart mobs and dark mobs, big companies are big targets; brands are still important, but they are increasingly vulnerable and fragile. Curiously and alarmingly, dark mobs and extreme fundamentalist groups tend to be most adept at new media use.

The testing ground for new bottom-up participation patterns will be the world of gaming, particularly the massive multiplayer online games and immersive environments. This type of entertainment is often self-generated, personal, experiential, and embodied. New skills from the world of immersive gaming, blogging, and peer-to-peer file sharing will filter into the workplace with next-generation workers.

The networked world is becoming a complex mix of virtual and physical, where place is layered with information in a new geoweb (what MIT calls the “Internet of things”). Sensors will be everywhere, acting on people’s behalf (on the good days). Connective technologies and mobility have created a host of local and distributed ways of belonging to organizations. Next-generation digital natives to this new networked world have never known life without connectivity. Today’s digital diasporas are social networks that have both “roots” and “wings,” so they can maintain deep ties and wide reach through a mix of media.

New technologies will give humans the ability to project their identity and presence online. Next-generation workers will be more comfortable in the world of online presence. Entertainment is today’s practice ground and proving ground for tomorrow’s workforce behaviors.

Networking knowledge will become important to success, for individuals and for organizations. A cohort of people with traditional networking skills and new media practices is defining a new index of networking intelligence—a networking IQ—that sets them apart from others. Networking IQ is basically the combination of traditional networking skills with the application of new media and technologies. IFTF research has identified the following six factors as being most important to networking IQ:

- Group participation: how you use networks to engage with others in effective ways.

- Referral behavior: how you use networks to link to other resources available through the network.

- Online lifestyle: how the network fits in the context of the rest of your life.

- Personal mobile computing: how you use the network as you move about.

- Locative activity: how you use the network to draw links to specific geographic locations.

- Computer connectivity: your skills in linking to computer-based resources.

37

If leaders are not skilled or at least conversant with blogs, wikis, and other networked media, it will be hard for them to lead. The fourth artifact from the future, the “Reputation Statement” artifact (fourth from the top at the far right of the Forecast Map), suggests how network IQ might be rewarded in the future.

Young people are learning to create and share knowledge in a mixed physical and virtual landscape. Where older workers still struggle with e-mail overload, young digital natives are more able to juggle multiple media, devices, and images. The explosion of social software will challenge traditional notions of focus, workflow, and productivity. Concentration skills will still be important, and perhaps the digital natives will be at a disadvantage with regard to degree of focus. However, the ability to sense context accurately through many channels will be a critical networking IQ ability.

The introduction of more virtual media is likely to increase the desire for meaningful face-to-face engagement. Paradoxically, the more time we spend communicating with others by way of machines (such as the phone, computer, or handheld), the more important face-to-face experiences become. In addition, the more time we spend working with globally distributed colleagues, the more important local connections become.

38

Storyline 4: Polarizing Extremes

Everything, and especially the proliferation of extreme views, is amplified on the Internet. No matter how strange or extreme their views are, people can find others with similar views on the Web and use the Web to organize their collective strangeness. Of course, both positive and negative social change can be organized through the Web, but somehow extreme groups seem more sophisticated at networking than the more moderate ones do. Extreme networks are not problems that can be “solved”; they are dilemmas that need to be managed. While extremist groups have new powers in this world, so do the forces of cooperation.

A dilemma of polarizing extremes: how to engage with extreme groups when you cannot please all of them, especially since they themselves do not agree?

Whether the world is becoming more extreme in its views is debatable, but certainly the extremes are amplified and more volatile. Worldwide, it appears that fundamentalist perspectives (religious, political, and social) are increasing in popularity. Not only do these groups adhere more strictly and literally to their doctrines but they may also reject the separation of sacred and secular life that has characterized much of Western culture over the past century.

Strong opinions, strongly held, will also get more mobile. Although the likelihood of large countries going to war against one another is low, the likelihood of insurgent warfare is high. Dark mobs will increasingly learn the lessons of smart mobs and, probably more so than more moderate groups, will become adept at using mobile technologies and networking mechanisms.

More people will become candidates for extreme fundamentalist views—especially if those people are hungry or hopeless. The gap between rich and poor magnifies this problem of extremes. The gap is difficult to take, especially since these differences are broadcast in everyday media to remind people on both sides of the gap. It is as if the rich rich and the poor poor live on opposite sides of the same street and look out at each other each day. Even if the rich ignore the poor, the poor are increasingly conscious of the excesses of the rich.

39

The 2006–2016 IFTF Map of the Decade points out the disturbing fact that the number of overweight people in the world is now equal to the number of underfed. Hungry and hopeless people are prime candidates for extreme groups who seek committed followers. If people are hungry and hopeless, their situation is already urgent, and the extreme groups offer at least some source of immediate aid and identity—as well as hope, no matter how unrealistic it may seem to others.

The “connected core” and “nonintegrated gap” regions of the world shown on the Forecast Map highlight the global gap between rich and poor—a gap that shadows the next decade and probably well beyond.8 For the first time in history, during the course of this decade more than half of the world’s population will live in cities. The shift will be greatest in developing countries. Megacities (cities with over 10 million people) will bring growing economic value and urban destitution in developing nations (e.g., China). Megacities will constitute a new kind of wilderness, resembling the most extreme ecologies in nature and eliciting adaptive survival strategies. At the same time, small cities with populations of less than 50,000 will be among the fastest growing in both the developing and developed worlds. There will be a growing distinction between the connected core of economically and technologically linked countries and the unintegrated regions that are less connected. Alongside this global shift in population from primarily rural to primarily urban, the unpredictable impacts of climate change are likely to inflict potentially disastrous effects in heavily populated areas.

These population shifts will strain existing institutions that provide both the infrastructure and social structures necessary for healthy human life. They will also threaten the old wildernesses as people attempt to escape urban congestion.

Dark innovation, innovation by extreme groups for their own advantage, will be important in the next decade, but anyone can learn from these innovations and reapply them in constructive ways. Try viewing again the 1982 movie Blade Runner, in which a young Harrison Ford plays the part of a maverick truth finder in a dark urban world of Los Angeles in the future. The most innovative scientists in Blade Runner are urban craftspeople working in the burned out core of an infrastructure that no longer functions in the way it was intended. Science continues, but the innovation is on the dark side and the forces of light are difficult to find.

40

In our world hacking is no longer just a marginal activity practiced by a few malcontents but rather a style of innovation that spawns major economic value not only in gray and black markets but also in legitimate markets. At the 2006 Maker Faire in San Mateo, California, organized by O’Reilly’s Make magazine, an entire pavilion was dedicated to people hacking Microsoft products in interesting ways. Microsoft sponsored the pavilion in what was a major shift from the company’s earlier stance that hacking was forbidden and severely punished whenever possible. Now, at least some forms of hacking are encouraged. There is a fine line between innovation and hacking. In many parts of the world, there is a fine line between innovation and theft.

Storyline 5: Health Insecurity

The baby boomers will fund and fuel what our health researchers at IFTF have come to call the “health economy.” The aging baby boomers are determined to change the aging process, just as they have changed everything else as they have matured. Many baby boomers seem to view death as an option that they are not planning to take. They are extremely concerned about their own health, and the wealthy among them are going to be the richest “retirees” in history. Technology drove the last wave of economic growth; health is likely to fuel the next. Health is the bottom line on the Forecast Map because, without health, the future becomes irrelevant. The future is only important to those who are healthy enough to enjoy it.

A health insecurity dilemma: how to grow a culture-of-health marketplace in the shadow of looming global health crises? How many will be able to afford to be healthy?

41

Many baby boomers will buy anything that will protect their health and well being and help them to stay active longer. Even if they can afford to retire, most baby boomers say they don’t want to do it—they just want to work on things they love to do.

As the boomers age, new medical technologies and treatments are making new promises (or perhaps delivering on old promises). In IFTF’s ongoing health horizons research we have studied the extremes of life enhancement and life extension in order to begin to sort out emerging patterns. Essentially, the next ten years will see new approaches to extending what the body can do in ways that have been difficult to imagine before. IFTF has identified these styles of creating an extended self:

- Identity switchers: those who strive to change their identity through mental and social disciplines.

- Medical modifiers: those who use medical or surgical methods to change their bodies in ways that they find positive.

- Body builders: those who use exercise and other disciplines to alter their physique.

- Death defiers: those who stretch the limits of what is possible and what is safe.

- Super connectors: those who use networks to amplify their sense of self and essentially develop a more connective definition of self.9

These real-life “X-Men” and “X-Women” are expanding the limits of what is possible, what is healthy, and—in some cases—what is human. They are using various approaches to extend their bodies, their minds, and their social reach. These people at the extremes help to bracket what is possible and motivate what is mainstream.

The language we use to talk about health is also changing; for example, we see the popular introduction of the term pandemic (a global or all-encompassing epidemic). The ability to isolate ourselves from global health issues is increasingly difficult because of the fluidity of international travel.

42

At IFTF, we have done expert panels on climate change since 1977. Until recently, most of the concern was at the fringes of science. Now, the mainstream of science is concerned, and most businesses are seriously considering the possibilities. We expect this concern to grow, along with the variety of responses. The gradual increase in global atmospheric temperature, which has been tracked over the past thirty years and will continue into the future, will have significant—but unpredictable— impacts.

Climate change is likely to have implications for global health. The human herd is not in a healthy state. We may well see declines in health indicators such as longevity and fertility drop and obesity and chronic disease grow.

There are many impediments to health today, in both the developed and developing worlds. Recent IFTF forecasts have highlighted these impediments in particular:

- Uninsurance: who will pay?

- Workforce shortages: particularly of doctors but also of other health care professionals, with big regional variations.

- Administrative waste: health care institutions have never been known for efficiency, but the problems are now highlighted and the solutions are not apparent.

- Medical error: even in the developed world, hospitals make mistakes.

- Lack of incentives for healthy behavior: threats of lawsuits play a role here, but so do other economic structures that make it hard to provide incentives for healthy behavior.

- Unhealthy behavior: even when it is clear what to do to be healthy, many people don’t do it.

- Increasing challenge of connection between health providers and consumers.

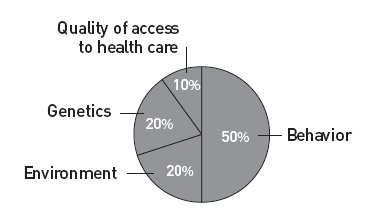

In research that IFTF did with the CDC, we concluded that the determinants of health status break down roughly as shown in Figure 2.1. The surprising and hopeful finding here is that whether you are healthy or not depends largely (50 percent) on your behavior— especially on factors like weight, fitness, smoking, and alcohol consumption. The degree of access to health care is the smallest contributor as a determinant, yet funding for health and health care in the United States is almost the inverse of these proportions. As a society, we continue to invest far more in disease response than we do in behavior change.

43

2.1 Determinants of Health Status

Nutrition plays a big role in health, yet nutritious eating is not easy, even in the so-called developed world. As science gets smarter about controlling interactions at the molecular level, engaged people are becoming more aware of their own body chemistry and are intervening in it to achieve health goals. As consumers get savvier about nutrition and food chemistry, they will likely use drugs (or food) to influence their physical health, and also their moods, personalities, and cognitive abilities. Expect engaged consumers to monitor their own body chemistry with increasing precision but varied levels of expertise. The fifth artifact from the future (bottom at the far right of the Forecast Map) suggests a possible “body hacking” movement as such consumers become more adventuresome.

Health concerns and environmental concerns are likely to be linked. The first Earth Day was in 1970, almost forty years ago. Now, finally, environmental concerns are coming to be viewed as mandatory for long-term success, not just as something that is nice to do. Global warming, climate change, destruction of resources, biodiversity, disruptions of sustainable food supplies, pandemics, and a host of other factors have driven this gradual shift—which is likely to hit an inflection point of concern within the next few years.

This is one of those forecasts, however, where forecasters have to be careful to distinguish between what they think will happen and what they want to happen. My biggest mistake as a forecaster was failing to anticipate the emergence of sport-utility vehicles (SUVs). Like many others, I experienced the oil crisis of the 1970s, and it seemed obvious to me that smaller cars would dominate the auto scene in the United States. What happened, of course, was something quite different. SUVs were and are a crazed concept from a societal and environmental point of view, but they made perfect sense to individual consumers who wanted a sense of security and control in an uncertain world where gas was still cheap.

Next-generation workers are sensitive to environmental concerns. All generations will be increasingly concerned about their own health, about healthy work environments, and about healthy lifestyles. Health will be defined broadly, to include beauty, nutrition, fitness, lifestyle, and even building supplies, for healthy environments at work and at home. Concern about global pandemics, bioterrorism, and chronic disease is likely to grow. Health and environmental concerns will become increasingly linked in the minds of many people, particularly since the next decade will see dramatic concern about fossil fuels, water, and global warming.

This forecast provides a base for the rest of the book, the foresight that will be used to provoke insight and action. What can we as leaders learn about leading effectively in this kind of future?

Leaders can use foresight of the kind discussed in this chapter to stimulate insights about what individuals and organizations might do. Again, you don’t have to agree with a forecast to find it useful.