184

10 Flexible Firms

Nothing in the world

is as soft, as weak as water.

Nothing else can wear away

the hard, the strong,

and remain unaltered.

Soft overcomes hard,

weak overcomes strong.

Everybody knows it,

nobody uses the knowledge.

—Lao Tzu, Tao Te Ching

This chapter builds on Chapter 9 and describes how the flexible firm is beginning to emerge. I include several real-world case studies of flexible firms and a vignette that stretches current experience into the future. This chapter gives a taste of what organizations and leaders can do to deal with dilemmas in creative and useful ways.

My purpose here is to bring the idea of the flexible firm to life. This chapter is only a beginning, of course, since the flexible firm is still being created, and new models are appearing all around us.

An Open-Source Flexing Story

IBM realized that the world was changing. What had worked for the company in the past was not going to work in the future. As IBM’s hardware and software business declined, it began a dramatic transformation that has allowed it to become a different kind of company. While it still supports hardware and software businesses, it makes money off of services. It used to sell computers, but now it sells computer services. In order to go open source, you have to think with foresight and flexibility.

IBM learned that it can’t make money from each new idea right away, but it is figuring out ways to leverage its ideas later in the process. Openness fuels innovation, with the potential for direct links to new business development. Open source for IBM includes:

- Co-production of value between competitors and users

- Celebration and incorporation of user-generated innovation

- Discovery of communities of interest and efficiencies among users, producers, distributors, partners, and employees

IBM has been able to create or participate in open-source or free zones where it gives away software in order to create a higher value competitive zone where it can offer services. It is cooperative and open in hardware and software but competitive in services. Essentially, it gives things away in order to grow a level playing field on which it is confident that it will win most of the time.

IBM faces a constant dilemma of both cooperating and competing with the same companies, depending on where they are in the cycle. Instead of being commoditized selling software and hardware with smaller and smaller margins, IBM shifted to licensing or even giving away basic platform tools (or co-developing them with competitors), but creating a high-value zone where it can compete in a world of much higher margins. In recent years, IBM has become much more collaborative and cooperative with its competitors and customers—as well as much less secretive. Big Blue has become much more of a network-style organization, providing a wide range of services.

IBM has now mounted a program to create a new academic discipline in services arts and sciences, in much the same way that it did in the late 1960s and early 1970s to help create the computer science discipline. This visionary move has value for both the economy and for IBM, since the new graduates from these programs will also become a labor pool for IBM to hire from.

186

IBM is creating new ways to win in the dilemma-laden world of computer services and systems. It went from selling customers a box to helping them manage the ongoing dilemmas of computer systems operations. It still positions its services as “solutions” but is interested in living solutions—not just one-time solutions. One-time solutions do not last for long in the world of computer systems and networks, because most solutions come with a need for ongoing support. Computers do solve specific problems, but they also create much larger dilemmas that need ongoing support.

The driving force of grassroots economics that was part of the Chapter 2 forecast will fuel growth of open source, as will smart networking. The future favors open source as a strong direction of change. Empowered users want open source; they want to influence the direction of the fields in which they are playing. IBM is a dramatic example of a slow-moving company of the past that saw change coming and transformed itself into a flexible firm in an impressive fashion.

An External R & D Flexing Story

Procter & Gamble’s CEO, A. G. Lafley, has said publicly that more than half of P&G’s new-product ideas should come from outside P&G. Chief Technology Officer Gil Cloyd is advocating a “connect and develop” strategy to draw on outside resources and innovations.

When I began working with P&G in 1977, my first project was to assess how the Internet (then called the ARPANET) might be used to grow what was then called the “invisible college” of R & D scientists within P&G worldwide. P&G was then, and still is, one of the largest science-based companies in the world. In 1977, the assumption was that innovation needed to occur mostly inside the firm, with a proprietary orientation that protected new ideas and new products from competitors.

It is remarkable indeed that, between 1977 and 2006, P&G has moved from an internal orientation toward innovation to one that is both internal and external — with an emphasis on outside sources of innovation. The strategy is even discussed in an article in the Harvard Business Review.1 In 1977, it would have been impossible to imagine P&G publishing its “new model for innovation” in the Harvard Business Review. Yet, in 2006, P&G’s more open strategy is completely consistent with the directions for change summarized in Chapter 2. P&G’s strategy is demonstrating flexibility. Its innovation networks are flexible, but its corporate values remain firm.

We are moving toward a much more open world. It is a both/and world where intellectual property is still important, but the intellectual property is generated and managed in different ways from the much more proprietary days of the past. Networks fuel this new world.

In 1977, the ARPANET was still oriented toward defense contractors at university and government agency research sites. Most of what went on was secretive, and some was classified. P&G wanted to learn from this experience and apply it internally at P&G.

Over the past thirty years, network structures have made it possible to create new networks for innovation, like the connect-and-develop strategy suggested by P&G. Hierarchies haven’t gone away, and they still play a useful function, but they come and go and are more flexible than before.

187

In a world of empowered consumers (the P&G mantra is “The consumer is boss”) who are also deeply networked, innovation needs to be connected to those networks—not isolated from them. Connect and develop is essentially a flexible networking strategy mounted by the world’s largest consumer products company to better link to its consumers and to outside sources of innovation.

A Geoweb Flexibility Story

As discussed in Chapter 2, the geoweb is the mixing of virtual and physical media to extend both our experience of the physical world and our access to online resources. Walt Disney World is already mixing the physical experience of the park with virtual links and is focusing attention on both the technology and the human efforts to work with the technology to provide great experiences for guests (Walt Disney World customers). Certainly technology will play a role, and many kids already come to theme parks as digital natives who are deeply at home in digital worlds. This is a story of my experience with an early geoweb innovation at Walt Disney World in Orlando:

Pal Mickey is a small Mickey Mouse stuffed animal that has a radio frequency (RF) reader in its nose and an ability to “talk” to the person who is holding him. As a guest goes around Walt Disney World, Pal Mickey gives updates on where the lines are shortest and points out local attractions that might be interesting to a guest. Pal Mickey also has jokes for the kids and a number of other verbal offerings that are only occasionally annoying for parents and almost always entertaining for kids.

When I carried one of the early Pal Mickeys at Walt Disney World in Orlando, however, mine stopped working. I brought my sick Pal Mickey to a nearby Disney stand to see if they could help. The cast member (Walt Disney World employee) told me, “No problem, I’ll give you a new Pal Mickey.” I responded that I had developed a personal relationship with this Pal Mickey and was hoping she might be able to heal him—rather than giving me a new one. The cast member was taken aback at first, but then she smiled, winked at me, and said she’d take my Pal Mickey and be right back. She went behind a curtain and returned a few minutes later with a fully operational Pal Mickey.

“We’re in luck,” she said, “I was able to find a doctor, and we were able to heal your Pal Mickey right here!”

I realized that she may have replaced my Pal Mickey behind the curtain, but I was charmed nonetheless. She had lived up to her challenge as a Disney cast member: to provide each guest with a “magical experience.” She also demonstrated that introducing virtual technology in a theme park is not an either/or choice between technology and human interaction. As a guest, I had an experience of technology with a human touch.

Pal Mickey is a small and interesting step toward a geoweb-enabled theme park, a progression that will move from episodic interactions with guests to always on within the park (if the guest chooses) and the potential for immersive interactive experiences as a guest moves around the park. In this scenario, the theme park becomes like a game board, with amplified everything in a physical and virtual reality that is only beginning to be imagined with today’s multiplayer games that combine virtual and physical worlds.

Kids are impatient and are used to working with multiple channels simultaneously. Theme parks are already stimulation rich, but the geoweb theme park could multiply and personalize the richness. A child, for example, could have one experience while the parent walking next to him has a very different experience.

Theme parks present new opportunities for all sorts of transformative entertainment. Just as massive multiplayer games are becoming the learning ground for workplace behavior in the future, geoweb theme parks could become the learning ground for creative linkages between the virtual and physical worlds. A large complex theme park will be able to offer both connected and escapist experiences—all in the same park at the same time.

The best technologies will become part of the landscape, part of the experience that is both reassuring to the parents and stimulating for the kids. The dilemma will be figuring out how to create magical theme park experiences that also employ virtual media as appropriate—without taking the guests or the cast members out of the park experience. How might technologies provide a great sense of safety for the parents while also providing thrills for the kids? We expect the linkages between physical and virtual to develop and become more engaging over the next decade.

190

This dilemma will be shaped by the geoweb, which will allow new possibilities to reimagine a theme park as a physical-virtual blend. Pal Mickey is just a beginning. Combine the geowebbed theme park with empowered and networked guests, and the experience could become even more magical. And theme parks may be the prototyping ground for experiences in other physical environments outside the park.

A Flexible Identity Story

In the emerging mix of physical and virtual worlds, corporations develop brands and online identities—but so do the people who work for corporations, either as full-time employees or as part of the broadening web of consultants, suppliers, alumni, and contractors that form the increasingly porous boundaries of the firm.

Most of all, leaders need to lead in both the in-person and virtual worlds. Each leader needs an online persona. The online persona is becoming increasingly important as our organizations become more distributed and leaders cannot “be there” in the traditional sense of being there in person most of the time.

An increasing number of employees—especially the twentysome-things or younger—are creating an online persona to go along with their real-world persona. What are the boundaries between a person’s “work self” and his or her “personal self”? When you Google someone, you begin to see his or her online presence, and it may or may not be consistent with the self-image that person projects in the real world—or the image that his or her employer would like to see projected.

In the online world, of course, someone can adopt alternate personalities, avatars, handles, or presences that express another aspect of their personality that they may or may not want to share with others in other worlds—such as the world of their employer. The employer’s dilemma is how to sort all of this out, not just in terms of potential problems for the company but also in terms of leadership and innovation opportunities. How does a company manage (you can’t control) work and personal identities that are associated with your brand? The personal dilemma here is a tension between a person’s virtual self (or selves) and their physical self. One does not solve this dilemma, since the worlds keep changing, as does the person and the organization(s) with whom they are working.

I offer a story from the near future, about a job interview and the personal dilemmas that are faced by this next-generation applicant for a job at a professional services firm as well as those faced by the baby boom partner who is interviewing him and trying to figure out what’s going on. Notice the multiple identities that the job candidate demonstrates, in a context that is more complicated than it seems. Notice how the partner doing the interview gets increasingly confused, since he is not comfortable with virtual identities and doesn’t know what to make of the job candidate. Still, the partner is intrigued:

The partner produced his card. “Steve Argyce, rhymes with ‘nice.’ Which I’m not,” he added. This was designed to throw the potential recruit off. “Sit down.”

The recruit, whose name was Winton Feyer, sat down and relaxed. Good. Steve approved. No reaction to his standard opening. He would be able to handle clients, who could easily turn demanding.

Winton did, however, have spiked hair and an earring. Nothing ostentatious, nothing vulgar. No spikes through the chin, no safety pins in the eyebrows. Probably that fad was over, but the iPod earphones draped around his shoulder suggested long use, in a habitual manner.

Warning flag, Steve noted. He probably spends most of his time playing Everquest or one of those other online games.

Well, he’d majored in philosophy. There was nothing wrong with that, per se.

Steve tented his fingertips and leaned forward slightly. “What philosophers do you particularly like?”

“None,” the boy answered. “Too much head-in-the-clouds, too much muddy thinking. I understand them, most of them, but I don’t really like them.”

“Really?” Steve made it sound skeptical, even critical.

“Really,” Winton stated, glancing around the room.

Steve suddenly felt self-conscious. It was such a typical hotel business center meeting room, with its neutral tones and paintings of sailboats on the wall. He quickly suppressed the feeling. He was the interviewer. “Do you play computer games?” he asked.

Winton almost smiled. “Of course. Doesn’t everyone?”

“Ah.” Steve made a note on the file. “Which one?” Not that he would know the difference. Already the candidate was losing ground.

“Well, it’s not really a computer game, but I’m into Second Life.”

“I see. Second Life. You don’t consider that a bit too much head-in-the-clouds, as you say? Muddy thinking, I believe was your term.”

“Not at all.”

“Why is that?”

“Because I have a small business there.”

“Business?”

“Yeah. I offer financial services.”

“I don’t think I understand. This is a game we’re talking about?”

“People have businesses in Second Life, and most of the online games. Some of them are very successful. They have bars, design clothes, the make things other players buy. But to build a business there you have to earn money, and it takes time to build up capital, just like in the real world. Sure, you can buy Second Life money online for real money, of course. But it seemed to me that for it to be realistic people should be able to borrow money in the game world, same as in the real one. So I started a financial services company. I started with small business loans. Did pretty well. Now I have an investment company.”

Steve was leaning forward and had to force himself to relax.

“An investment company,” he repeated. “In the game?”

“Sure. We do venture capital, leveraged buyouts, mergers and acquisitions, that sort of thing. And of course we offer accounting services. If we didn’t, I wouldn’t be here, would I?”

“I suppose not. But you said we?”

Winton shrugged. “Sure. Business got too big for one person, especially one who had to write a senior thesis on Kierkegaard, so I took on some partners and started a network.”

Steve chewed on his lower lip and read a few lines of the file while he considered how to continue. It wasn’t that the interview was out of control, not really, but it was taking some surprising turns. Should he ask about the partners, or ask about Kierkegaard? He closed the file. “How many partners do you have in your network?”

Winton smiled. “Honestly, I don’t know.”

“You don’t know how many partners you have?” Steve asked absently. He had already closed the file folder and begun planning to gracefully terminate the interview.

“No. It depends on whether you mean in the real world, or online.”

In spite of himself, Steve said, “I don’t understand.”

“Well, most people, though I’m not one of them, have more than one identity in the virtual world. They may have several avatars in there, each a different character with different interests, maybe different genders. So some of my partners may in fact be the same person in the real world. I suspect three are at least doubling. One I’m pretty sure is a triple. So if in Second Life I have fourteen partners, in the real world there are likely many fewer. By doubling like that, they make more money.”

Steve was trying to imagine one of the partners in his firm having a double or triple career. The image made him smile.

“How is that possible?”

“They can sell into the different markets, the various communities where they have a presence. Really, Mr. Argyce, I imagine at your firm two partners make a great deal more than one. Same thing, except in the real world it probably isn’t as easy.”

Steve didn’t bother to reply to this. “If your business is too much work for one person, how can the others double up, as you say?”

Winton laughed. “They just sell into the various groups where they have identities. Some people spend way more time in there than I do. And I don’t sell, I just create product and advise. Really, the business pretty much runs itself these days.”

“And you make money on this?”

Winton shrugged. “Last year about a hundred twenty thousand.”

“Game money, of course.”

“No, no, I cash in. That’s dollars.”

Steve reopened the file folder. He now wasn’t sure he would be able to make an offer the boy would accept. When he finished his thesis on Kierkegaard, of course.

In-person and online identities already mix, in ways that are difficult to sort out. The world of this story is almost here already, and some would argue that it is here for a few serious players. The mixes of real-world and virtual identities, however, are about to become much more complex—with many more creative possibilities and many more risks. The ability to flex will be mandatory, for the firm and for the players in the firm of all ages. Each leader will need to manage his or her own virtual identity, in addition to his or her real-world identity. For example, Jane McGonigal, one of the bright stars of gaming and immersive experiences, came to IFTF recently to do a seminar. I met her afterward and gave her one of my cards. In response, instead of giving me a card, she said, “Just Google ‘Jane’ and ‘games.’” Her virtual identity is so well established that she really doesn’t need business cards. Her identity is linked to gaming, so her “business card” is the search engine link between her first name and games. This association sends an important message that accurately reflects her professional identity.

The foresight in this vignette suggests that we are moving toward an increasingly anytime, anyplace world, where work gets done at many places and at many times. In an anytime, anyplace world, flexibility is a good thing for workers and for the firm, but there are downside risks. If it is possible to work anyplace, anytime, some people will try to do it, and some managers will try to require it. Leadership in the mixed-media world will be different from leadership in a physical office alone. Immersive environments, as suggested in the vignette, are the training ground for the leadership style of the future.

195

Social Venture Flexing

The Social Venture Network (SVN) was started in 1987 by a handful of visionary leaders seeking to promote socially responsible and sustainable businesses. The network champions the “triple bottom line” of business — people, planet, and profit. Member companies are committed to doing good while doing well, or as the SVN puts it, “value healthy communities and the human spirit as well as high returns.”2 Recognizing the importance of information access, especially in an environment of experimentation and innovation, the SVN connects different enterprises and creates a community of collaboration. Member companies strive to influence public policy for the common good, make markets beneficial and economies ethical, and ensure that their values inform their actions.

For example, consider how the Social Venture Network addressed the dilemma of youth in prisons:

Imprisoned youth face a sea of difficulty—frequent abuse, little support, and sparse if any rehabilitation services. Eighty percent transition to the adult prison system. A group of SVN members, all approaching this issue from different angles, created a series of better alternatives.

By rallying activist parents, developing a documentary, and lobbying in the California legislature, SVN helped bring about a one-third drop in the state’s youth prison population.

The prison dilemma has no absolute solutions, but progress is possible. The reality is that youth commit crimes, and prison funding is low. Most people don’t want to face the reality of prisons, much less youth prisons. Media has been saturated with stories of prisoner abuse; these stories can both raise awareness and desensitize people to the facts.

Mobilizing parental support (a section of the population clearly interested in the prison situation) and an organization focused on human rights documentaries (to confront the public and policy makers with the facts), members of SVN mounted a comprehensive multidisciplinary approach to the dilemma of youth incarceration. They navigated between the various factors to target the core issue: the unnecessarily negative experience of incarcerated youth and their lack of support.

196

The Social Venture Network understands that networks of people bound by common values and connected through technology are vital in this VUCA world. Members are applying the practices of venture capital to the higher principles of social change.

Principles for Flexibility

Leaders have a special role in creating islands of stability and coherence that workers will expect in workplaces—both physical and virtual. The new flexibility clearly involves space, tools, and protocols for working.

At Institute for the Future, we created our own core principles in the mid-1990s, stimulated by the work of Dee Hock, who believes that principles-based organizations have much more flexibility to be able to respond creatively to uncertainty.3 If you have strong principles and strong people, you don’t need many rules. Rules are more rigid and brittle than principles. Of course, it takes a long time to develop a consensus and belief around core principles. Once the principles are established, however, they can grow into a sustainable core. I offer these principles not because they will be right for every organization but to share a real example of principles that are specific enough to guide behavior yet are open-ended enough to allow for flexibility and individual creativity. These are operational principles that guide the work of IFTF as we interact with one another and with the outside world:

- Get There Early: We pursue research topics early, before others move in. We focus three to five years into the future, as far as ten years when we can, and as far as twenty years or more in the future occasionally. We work just beyond the normal thought horizons of our best clients. Getting there early means acceptance of high uncertainty. Getting there early also means we meet our project deadlines, we keep our promises, and we start and end meetings on time.

- Pursue Public Good: IFTF is an independent nonprofit research group, and we have a responsibility to our clients, since we depend financially on organizations that value our research. We are professional bystanders, honest brokers between the known and the unknown, the imagined and the unimagined.

- Courageous Opinions, Humbly Expressed: Diversity of perspectives is mandatory if we are going to understand multiple futures and distinguish between what is new and what is important. We use many methods to explore the future. We seek provocative forecasts and strong points of view, but ones that are expressed with humility, respect for others, and thoughtful reflection on alternative views.

- Give Generously, Ask Respectfully: We work as teams, and we need one another. We need to be direct with one another and express our opinions honestly, not through back channels. We value silence, listening, and reflective abilities as much as we value speed.

- Work Less, Learn More: We each design our own training and educational programs so we can growth within IFTF. As an organization, we enable, encourage, and require such continuous personal growth. Since we encourage long-term continuity in staff, we must facilitate serial “careers” for everyone while they continue working at IFTF. We foster an intense work environment, but one that is family-friendly and respectful of the spiritual sides of life.

- Honor Essential Processes: We are committed to a few simple core business practices at IFTF, which, if they are unanimously followed, allow great freedom for individual researchers and project teams. We minimize administrative and management procedures.

198

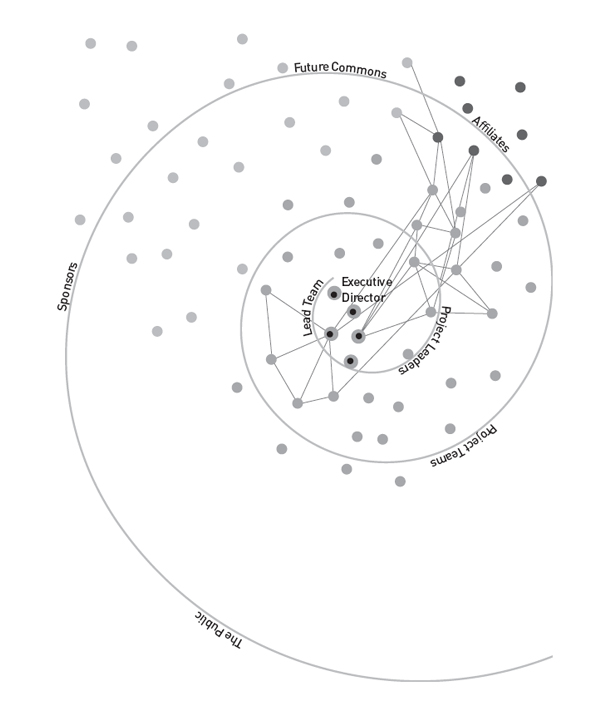

10.1 IFTF’s Organization Chart: Organic and Circular

It is the responsibility of all leaders at IFTF to make sure that these principles are put into practice in research and administrative work and that all new staff members understand them, both in concept and in practice. The principles are reviewed periodically to make sure that they continue to represent the best wisdom of the group and that there is a common understanding of them, but the principles don’t change often.

199

It is the responsibility of the executive director to ensure that the basic principles continue to express the best wisdom about how IFTF aspires to operate and that the principles form the basis of performance reviews at all levels in the organization. If any staff member consistently violates the principles, it is the responsibility of the executive director to correct the problem or terminate that person’s connection to IFTF’s network.

Since the structure of IFTF is a network, not just a hierarchy, we wanted to have a different kind of organization chart. (See Figure 10.1.) I expect many new models will take the place of traditional organization charts that are arranged in hierarchical fashion. Again, I doubt that the IFTF model will apply to your organization, but I hope it stimulates thought about alternatives to the traditional organization chart.

This structure is intentionally organic and circular, ringing out in a network structure from a core group in the center. We are an independent nonprofit, so we need a public orientation while being independent from our sponsors. In our case, the core group of full-time people is about thirty, the next ring out (what we call “the Affiliates”) is up to about a hundred less-than-full-time people, and the “Future Commons” is up to about a thousand fellow travelers around the world. Hierarchies come and go at IFTF, usually in the context of projects. In a sense, the highest-ranking person at IFTF is the project leader, and many of the teams are formed on an ad hoc basis. This organizational model gives a basis for making decisions about where work gets done.

The examples in this chapter provide an early hint of what is possible as firms learn how to stretch their own abilities to flex. The next ten years will be critical, with a whole new range of options for flexible work as the geoweb unfolds and as our networking skills improve. The vision of being flexibly firm is possible, and in many cases it will be required.