2

Process Improvement and Lean Six Sigma

IN A NUTSHELL

This chapter describes the need for an LSS quality focus on business processes. It introduces process improvement (PI), describing the characteristics of business processes and explaining the advantages of using a cross-functional focus. When you complete this chapter, you should be able to:

- Explain what is meant by LSS quality focus on the organization’s processes

- Explain the need for PI

- Describe the objectives of PI

- Explain the advantages of PI

- Explain what a business process is

- Explain the difference between traditional views of management and the process view

- Explain how the owner of a business process is selected

- Describe the authority and responsibilities of a business process owner

- Describe the composition and function of the Process Management Committee (PMC) and the Process Improvement Team (PIT), also known as the Six Sigma Team (SST)

INTRODUCTION

It is no secret that the 21st-century business environment is changing rapidly. The present environment is more competitive than it was in the past, with competition coming from both domestic and international global sources. In addition, there is increased emphasis on the quality of the products and services that businesses provide to their customers. Because of these changes, many businesses are discovering that the old ways of doing business no longer work so well. Many businesses have found it necessary to re-evaluate their corporate goals, procedures, and support structure. In one such corporate re-evaluation, the discovery that the support structure was not keeping pace with the changes led to the development of a management approach known as process improvement (PI). PI emphasizes both quality and excellence. It looks at the function of business management on the basis of processes rather than organizational structure.

AN LSS QUALITY FOCUS ON THE BUSINESS PROCESS

In 1978 many large manufacturers had relatively stable product lines that were offered through two or maybe three marketing channels, and usually shipped through one distribution channel. By 1994, however, manufacturers had almost tripled their number of products, offering them through seven or more marketing channels and shipping them through four to five distribution channels. Such rapid growth is not unusual in many organizations.

Due in large part to such growth, many corporations found that their sales representatives were spending far more time on administrative details and paperwork. In fact, the productive sales time of the corporation’s marketing staff had dropped from an average of 40% in 1978–1980 to only 5% in 1994! Why? What could have caused this change? Compared to similar periods in the past, the corporation’s growth rate was unprecedented. Moreover, systems and procedures that were adequate in 1978 were clearly out-of-date by 1994. More products meant more procedures, more complexity, and more internal competition for limited resources—human and other. In turn, this meant an even greater workload for an already strained support structure.

In addition, the company’s various operating units were struggling to meet their own objectives, with little or no attention to the relationship of their work product to that of any other operating unit in the business. Driven partly by the resulting problems and partly by a re-emphasis on quality, corporate management decided to act. It provided the leadership and set the tone for making the needed changes by introducing the concept of process management in the corporate-wide instruction. Figure 2.1 shows the first page of a sample corporate instruction with an LSS focus.

First page of a sample corporate instruction with a LSS quality focus.

SOME BASIC DEFINITIONS

A corporate instruction like that in Figure 2.1 is important because it demonstrates top management commitment to LSS and provides basic guidelines for implementation. This philosophy is based primarily on the following statement in the corporate instruction: “Our business operations can be characterized as a set of interrelated processes.”

LSS seeks to focus management attention on the fundamental processes that, when taken together, actually drive the organization. Figure 2.1 also introduces several important terms that are key to the LSS process improvement approach. Among these are customer, requirements, and quality.

Definition: A customer is any user of the business process’s output. Although we usually think of customers as those to whom the corporation sells a product or service, most customers of business processes actually work within the same corporation and do not actually buy the corporation’s products or services.

Definition: Requirements are the statement of customer needs and expectations that a product or service must satisfy.

Definition: Quality means conformance to customer requirements. In other words, since requirements represent the customer’s needs and expectations, a quality focus on the business process asks that every business process meet the needs of its customers.

Definition: A business process is the organization of people, equipment, energy, procedures, and material into the work activities needed to produce a specified end result (work product). It is a sequence of repeatable activities that have measurable inputs, value-added activities, and measurable outputs. Some major business processes are the same in almost all businesses and similar organizations. Some typical business processes are listed in Table 2.1. Of course, some business processes are unique to a particular business and may be industry related. For example, steelmaking obviously has some processes, such as the foundry or slag disposal, not found in other industries.

OBJECTIVES OF PROCESS IMPROVEMENT

Process improvement is a disciplined management approach. It applies prevention methodologies to implement and improve business processes in order to achieve the process management objectives of effectiveness, efficiency, and adaptability. These are three more key LSS terms introduced in Figure 2.1.

Typical Business Processes

| Accounts Receivable | Production Control |

| Backlog Management | Field Parts |

| Billing | Inventory Control |

| Service Reporting | Commissions |

| Customer Master Records | Personnel |

| Distribution | Payroll |

| Procurement | Order Processing |

| Finance/Accounting | Field Asset Management |

| Research and Development | Material Management |

| Public Relations | Traffic |

| Customer Relations | Supply Chain Mgt. |

- An effective process produces output that conforms to customer requirements (the basic definition of quality). The lack of process effectiveness is measured by the degree to which the process output does not conform to customer requirements (that is, by the output’s degree of defect). This is LSS’s first aim—to develop processes that are effective.

- An efficient process produces the required output at the lowest possible (minimum) cost. That is, the process avoids waste or loss of resources in producing the required output. Process efficiency is measured by the ratio of required output to the cost of producing that output. This cost is expressed in units of applied resources (dollars, hours, energy, etc.). This is LSS’s second aim—to increase process efficiency without loss of effectiveness.

- An adaptable process is designed to maintain effectiveness and efficiency as customer requirements and the environment change. The process is deemed adaptable when there is agreement among the suppliers, owners, and customers that the process will meet requirements throughout the strategic (3- to 5-year outlook) period. This is LSS’s third aim—to develop processes that can adapt to change without loss of effectiveness and efficiency.

CROSS-FUNCTIONAL FOCUS

Essential to the success of the process management approach is the concept of cross-functional focus, one of the few truly unique concepts of the LSS approach. Cross-functional focus is the effort to define the flow of work products according to their sequence of activities, independent of functional or operating-unit boundaries. In other words, LSS recognizes that a department or similar operating unit is normally responsible for only a part of a business process. A cross-functional focus permits you to view and manage a process as a single entity, or as the sum of its parts.

CRITICAL SUCCESS FACTORS

While not altogether unique, the concept of critical success factors also plays an important role in the LSS approach. Critical success factors are those few key areas of activity in which favorable results are absolutely necessary for the process to achieve its objectives. In other words, critical success factors are the things that must go right or the entire process will fail. For example, payroll as a process has numerous objectives and performs many activities, but certainly its primary objective is to deliver paychecks on time. If payroll fails to deliver checks on time, it has failed in its major purpose, even if all its other objectives are met. Therefore, on-time check delivery is the most critical success factor for payroll. Payroll has other critical success factors, but these are invariably less important. In implementing LSS, it is important to identify and prioritize the critical success factors of the process and then to use the LSS methodology to analyze and improve them in sequence.

NATURE OF LSS PROCESS IMPROVEMENT

In addition to the key concepts just introduced, LSS uses many accepted standards of management and professional excellence. Among these standards are:

- Management leadership

- Professionalism

- Attention to detail

- Excellence

- Basics of quality improvement

- Measurement and control

- Customer satisfaction

What is new in process management is the way LSS applies these standards to the core concepts of ownership and cross-functional focus. In the following chapters the key elements of managing a process are introduced and topics already introduced are elaborated. However, it should be noted that identifying and defining a business process almost always precedes the selection of the process owner. That is, you first identify the process, and then you identify the right person to own it. This seemingly out-of-sequence approach is taken in order to firmly establish and reinforce the key concepts of LSS before getting into how-to-do-it details.

Advantages of LSS Process Improvement

Management styles and philosophies abound within the framework of LSS. There are some similarities to such approaches as value stream management, participative management, excellence teams, and management by objectives. That is not unusual, since all of these approaches are based on the management standards mentioned earlier. However, LSS has advantages that make it both useful and relatively easy to implement:

- LSS, through its cross-functional focus, identifies true business processes. It bypasses functional and operating-unit boundaries that may have little to do with the actual process or that may obscure the view of the overall process.

- LSS, through its emphasis on critical success factors, gives early and consistent attention to the essential activities of the process. It provides a means of prioritizing so that less important activities are identified, but action on them is delayed until the more important ones have been addressed.

- LSS improves process flow by requiring the total involvement of suppliers, owners, and customers, and by assuring that they all have the same understanding of process requirements.

- LSS is more efficient than other methods in that it can be implemented process by process. It does not require simultaneous examination and analysis of all of a corporation’s processes. With management leadership and guidance, workers implement LSS within their process while continuing their regular duties.

DETERMINING PROCESS OWNERSHIP

As previously described, the nature of business processes is how they often cross organizational boundaries. It is important to describe process ownership, show how the process owner is selected, and describe the responsibilities and authority of the process owner. LSS stresses a cross-functional focus instead of the traditional hierarchy-of-management approach. LSS requires a process owner with authority to cross functional or operating-unit boundaries in order to ensure the overall success of the process.

Because the role of the process owner is at the heart of LSS, it is extremely important that top management understand and accept the principles presented in this chapter. Without the active support of top management, the process owner cannot function properly, and thus LSS will fail.

Selection of a process owner follows the identification and definition of the process, which is covered later. The purpose in discussing process ownership first is to give a broad portrayal of the environment over which the owner must have authority and responsibility. This, in turn, will provide an understanding of process improvement that is far more comprehensive than any simple definition of the term.

The Nature of Business Processes

By definition, LSS emphasizes the management of organizational processes, not business operating units (departments, divisions, etc.). Although a set of activities that comprise a process may exist entirely within one operating unit, a process more commonly crosses operating-unit boundaries. In LSS, a process is always defined independently of operating units.

Management’s Traditional Focus

The traditional management of a business process has been portrayed in the form of an organization (pyramid) chart. This “chain of command” management hierarchy has worked very well for many corporations over the years. So why does LSS seem to question this traditional approach? Actually, the traditional approach is not being questioned so much as it is being redirected. Process ownership is intended not as a replacement of the traditional organizational structure, but as a complement to it, a complement with a specific goal. The goal is to address the fact that the traditional structure often fosters a somewhat narrow approach to managing the whole business.

Typically, a manager’s objectives are developed around those of some operating unit of the business in which he or she is working at the moment. This emphasis on operating-unit objectives may create competition rather than cooperation within the business as a whole as managers vie for the resources to accomplish those objectives. With rare exceptions, these managers are responsible for only a small portion of the larger processes that, collectively, define a particular business in its entirety. Examples of these major business processes are shown in Table 2.1. In addition, the recognition and rewards system is almost always tied directly to the degree of success achieved in the pursuit of those operational objectives. So there is no particular motivation for managers to tie their personal goals to the larger—and more important—process goals. LSS seeks to address these common deficiencies through the concept of process ownership.

Cross-Functional Focus

In one large manufacturing corporation an internal review of its special/custom features (S/CF) process disclosed some serious control weaknesses and identified the lack of ownership as the major contributing cause. (S/CFs are devices that can be either plant or field installed to modify other equipment for some specialized task.) The S/CF process was a multimillion-dollar business in its own right and touched almost every other department in the corporation—order entry, manufacturing, inventory control, distribution, billing, service, and so on. Yet the review found that the process had no central owner—no one person who was responsible for the process from initial order to final disposition, no one who provided overall direction and a cohesive strategy for this cross-functional process.

Because business processes such as S/CF cross operating-unit lines, the management of these processes cannot be left entirely to the managers of the various departments within the process. With no one in overall charge of the S/CF process, the disruption caused by lost orders, incorrect shipping, and wrong billings is difficult to eliminate. Each manager can pass the buck, saying someone else is responsible. No one manager has the authority to solve process-wide problems.

Owner’s cross-functional perspective of the S/CF process.

If no one person is in charge of the S/CF process flow shown in Figure 2.2, the success of the process depends on the four managers of the four departments, for whom S/CF may be only a minor task in their departments. However, if one person is in charge, he or she can view the process with a cross-functional focus, emphasizing the process rather than the departments. The figure shows an owner’s cross-functional perspective of the S/CF process.

PROCESS OWNERSHIP

As shown above, process management requires an understanding of the fundamental importance of cross-functional focus. Clearly, there is a need to have someone in charge of the entire process—a process owner. While this chapter deals primarily with ownership of the major processes and sub-processes of a business, the concept of ownership applies at every level of the business. For example, the purchasing process can be broken down into various levels of components, such as competitive bidding and the verification of goods and services received. The components of a process are examined further in Section 2.

Because business processes often cross functional or operating-unit boundaries, it is generally true that no one manager is responsible for the entire process. LSS addresses this point through another unique concept— process ownership.

The Process Owner

The process owner is the manager within the process who has responsibility and authority for the overall process results. The process owner assumes these duties in addition to his or her ongoing functional or operating-unit duties, and is supported by a PMC, described below. The process owner is responsible for the entire process, but does not replace managers of departments containing one or more process components. Each component continues to exist within its own function or operating unit and continues to be managed by the managers of that function or operating unit.

Normally, the term process owner is used in connection with major business processes, either corporate-wide (for example, the general manager of a plant owns the process of manufacturing a particular product). On a practical level, however, an executive is often somewhat removed from the day-to-day operation of the process. Consequently, it has been found useful to implement a two-tier approach, in which the executive (vice president of finance) is referred to as the focus owner, and a subordinate, but still high-level, manager (for example, the controller) is referred to as the functional owner. In general, the functional owner has all the authority and responsibility of the focus owner except for the ultimate responsibility for the success of the process.

The Process Management Committee

Headed by the focus owner, the PMC is a group of managers who collectively share the responsibilities related to the committee’s mission. The committee has the following characteristics:

- All process activities are represented.

- The senior/top manager of the parent function for each activity is a member.

- The members are peer level, to the degree possible.

In practice, an owner should never be a lower-level manager than other members of the committee. When differences of opinion arise, a lower-level owner would have difficulty exercising his or her authority.

The mission of the PMC is to:

- Steer and direct the process toward quality objectives

- Support and commit the assignment of resources

- Ensure that requirements and measurements are established

- Resolve conflicts over objectives, priorities, and resources

The PMC mission can be expanded to accommodate unique process conditions. Issues related to the PMC mission are raised by the functional owner when, as often happens, he or she has been unable to resolve the issue with the Process Quality Team, discussed below. It is important for the credibility and effectiveness of the functional owner that issues raised to the focus owner and PMC be addressed and resolved promptly.

The Process Quality Team

Headed by the functional owner, the Process Improvement Team (PIT) is made up of lower-level managers. Preferably, they are peers of the functional owner and work for members of the PMC. The members of the PIT are the designated implementers of process management actions, which are to:

- Establish the basics of process quality management

- Conduct ongoing activities to ensure process effectiveness, efficiency, and adaptability

The functional owner and the PIT may be unable to resolve some issue, such as resource allocation, expense reductions, or process change. In that case, the issue should be brought to the focus owner for resolution through the PMC.

SELECTION, RESPONSIBILITIES, AND AUTHORITY OF THE PROCESS OWNER

The rest of this chapter covers process owner selection, responsibilities, and authority. It concentrates on the role of the focus owner, but adds perspective on the PMC and the functional owner as well. But first, it is important to remember that all three elements—selection, responsibilities, and authority—are needed. A process owner, with detailed and specific responsibilities (which will be described shortly), cannot function without commensurate authority. Just as important, all of the concerned parties within the process must be made aware of both the owner’s role and their own. And once ownership is established, in all its elements, the owner must get ongoing and visible support from both executive and peer managers.

Selection of the Process Owner

As mentioned earlier, process ownership is not intended to override the existing management structure. The process owner is defined, in part, as a manager within the process. The process owner continues in his or her current position, and simply takes on additional duties as head of the overall process. The other managers within the process become members of the PMC. Top management normally appoints the process owner. The question of which manager to choose as the process owner can often be answered by applying two words: most and best. That is, which manager in the process has the most resources invested, does the most work, feels the most pain when things go wrong, gets the most benefit/gain/credit when things go right? Which manager has the best chance of affecting or influencing positive change—perhaps because he or she is in the best position to do so?

For the most part, answers to these questions should clearly identify the best candidate for the ownership role. At the very least, the answers should narrow the field, in which case, the concept of critical success factors comes into play once again. That is, of the remaining candidates, which one currently manages the activities most critical to the success of the overall process? In addition, the process owner should be acknowledged as having the personal and professional qualities necessary for the job and a track record to accompany them. He or she should be comfortable dealing at high levels, be able to create and execute a plan, be a skilled negotiator successful at gaining consensus, and be a team player.

Responsibilities of the Process Owner

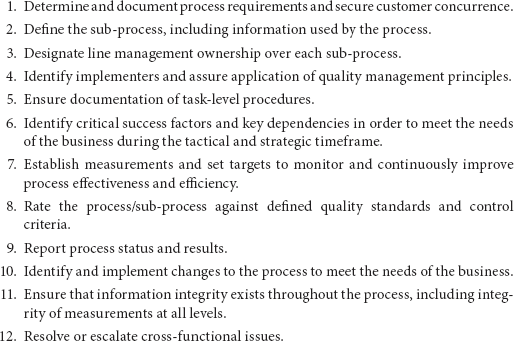

In general, the process owner is responsible for making sure that the process is effective, efficient, and adaptable, and as discussed in later chapters, for getting it certified. More specifically, Figure 2.3 lists the 12 responsibilities of a process owner, above and beyond that person’s normal job responsibilities.

It is also important for the process owner to create an environment in which defect prevention is the most highly regarded “quality” attribute. In many enterprises it is all too common to find that the most visible rewards go to the “troubleshooters” or “problem fixers.” Those individuals who consistently strive for defect-free results often go unrecognized and unrewarded.

Ownership responsibilities.

Authority of the Process Owner

Given the key elements of ownership selection, it is obvious that the process owner already has a great deal of inherent authority within the process. That is, if a manager meets all or most of the selection criteria, he or she is probably already in a fairly authoritative position in the process. Nevertheless, the issue of authority cannot be taken for granted. The process owner must have the right combination of peer and top management support to get the job done. Top management provides the greatest contribution by validating the owner’s authority through various forms of direct and indirect concurrence and support, including the following six areas:

- Approving resource allocation

- Financing the process

- Providing recognition for the owner

- Running interference

- Cutting the red tape

- Backing the focus owner or functional owner when issues have to be escalated

It is not enough for the process owner to have the necessary authority, however. All concerned parties within the process must clearly understand the authority being vested in the process owner. The process owner can first be told of his or her responsibilities and authority through a performance plan or job description. The next step is a formal announcement or, at the very least, an announcement to all managers throughout the process. If necessary, or if considered helpful, the PMC can create a written agreement defining and clarifying the various relationships. However it is done, there must be clear communication to all concerned parties regarding who has been selected, what authority is being vested in that manager, and what that manager’s responsibilities are. And top management must continue to support the process owner by doing whatever necessary to show that the owner’s authority is real. Only with this sort of strong, continuing support from senior management can LSS work.

PROCESS DEFINITION AND THE PROCESS MODEL

Once the focus owners of major business processes are identified, the existing managers within the process would begin to define and model the lower-level processes and sub-processes. This is accompanied by meeting in logical work groups from within the major process. For example, within the major process of finance, logical groups may include accounting managers for the lower-level accounting process and payroll managers for the lower-level payroll process.

A process model is a detailed representation of the process as it currently exists. When preparing the model, it is important to avoid the temptation to describe the process as it should be, or as one would like it to be. The model may be written, graphic, or mathematical. The model can take several forms, but the preferable, recommended form is a process flowchart, described in Section 2. Whatever form is used, the model must contain supporting textual documentation, such as a manual or a set of job descriptions.

The definition of a business process must clearly identify the following:

- The boundaries of the process and all of its components

- All of the suppliers and customers of the process and the inputs and outputs for each

- The requirements for the process suppliers and from the process customers

- The measurements and controls used to insure conformance to requirements

The model and supporting documentation are used as the base tools for analyzing how the process can be simplified, improved, or changed.

Definition of Process Mission and Scope

The first thing to be done, once ownership has been established, is to define the mission, or purpose, of the process, and to identify the process scope. But defining the mission and identifying the scope are not as easy as they sound. The mission of a process is its purpose—what the process is in existence to do. The mission clearly identifies exactly what the process does, from beginning to end, especially for someone not working within the process; the mission also describes how the process helps to attain the corporate goals.

The mission statement does not have to be lengthy or elaborate. It should be concise and to the point. Figure 2.4 shows a mission statement for a procurement process.

The scope of a business process is defined by identifying where the process begins and ends. These are the boundaries of the process. By identifying the boundaries, you identify the scope, just as boundaries tell you how much land a piece of property covers. There may be disagreements over the exact scope of a process. Such a disagreement might occur, for example, over whether a particular activity is the last activity of one process or the first activity of the next process. In settling disagreements about the scope of a process, it helps to identify the process whose mission is most clearly related to the activity in question. It may also require the help of some of the customers and suppliers of the process. Most importantly, you should concentrate on how the activity in question affects, or is affected by, the critical success factors of the process. As you remember, critical success factors are those few, key areas of activity that must succeed in order for the entire process to achieve its goals.

Mission statement: Procurement process.

To define the scope of a process, then, all parties must agree on the answers to four questions:

- Where does the process start?

- What does the process include?

- What does the process not include?

- Where does the process end?

The question of what a process does not include should be addressed even if there appears to be complete agreement on what it does include. Often, when discussing what the process includes, people make assumptions. (For example, if the process includes X, it must include Y and cannot include Z.) Only by agreeing on what the process does not include can you be sure that you have avoided making any such assumptions.

Even in well-established processes, there often is disagreement on answers to these four questions. Moreover, the questions deal only with a broad overview of the scope. The task of a process definition gets more complex later on as you detail all of the activities and tasks that go on within the process. That is another reason for beginning the definition of mission and scope by focusing on critical success factors. The mission and scope should both be written by the owner and the team. Neither has to be elaborate.

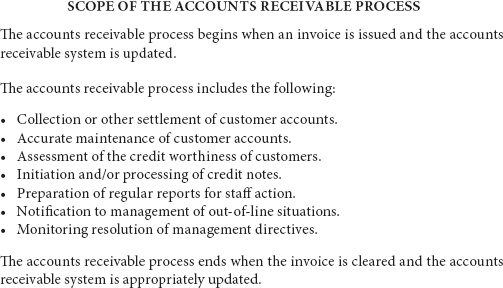

Figure 2.5 shows the scope of the accounts receivable process, as written by an accounts receivable group. Figure 2.6 shows the mission and scope of the procurement process, as written by a procurement group. These figures give a clear picture of the broad components of each process.

Scope statement: Accounts receivable process.

Mission and scope statement: Procurement process.

SUMMARY

This chapter has given you a general introduction to LSS and its connection to process improvement. Process improvement has been the focus of quality initiatives since the 1970s. Initially the focus was on manufacturing processes, but as the service industry became a major driver of the nation’s revenue stream and the overhead costs in any production organization exceeded the direct labor costs, emphasis shifted to business process improvement. In the 1980s organizations like IBM, Hewlett-Packard, Boeing, and AT&T developed programs to make step function improvements in their business processes, resulting in decreasing costs of the business processes as much as 90%, while decreasing cycle time from months to days or even hours. Methodologies like benchmarking, business process improvement, process redesign, and process re-engineering became the tools of the trade for the process improvement engineer during the 1990s. This focus on process improvement was driven by the realization that most of the major processes within an organization run across functions, and that optimizing the efficiency and effectiveness of an individual function’s part of these processes often resulted in sub-optimizing the process as a whole.

The designers of the LSS methodology recognized early in the cycle the importance of focusing upon process improvement and, as a result, incorporated the best parts of the methodologies that were so effectively used in the 1980s and 1990s. Throughout this chapter we pointed out how LSS has built upon the business process improvement techniques used in the 1980s and 1990s, modifying them to meet the high-tech, rapid changing environments facing organizations in the 21st century.

EXERCISE

- What does the term business process mean?

- If an effective process is one that conforms to customer requirements, what is an efficient process?

- What is an adaptable process?

- What is cross-functional focus?

- If your corporation has official goals, what are they? If not, what do you think they might be?

- List five or six of the business processes that exist in your corporation.

- List what you believe are the three or four critical success factors of your corporation.

- If your corporation has a formal quality policy statement, list the three most important elements of that policy (from your point of view).

- What is the difference between functional owner and focus owner?

- What is the role of the Process Quality Team (PQT)?

- What bearing do critical success factors have on the selection of a process owner?

- What is the relationship between process ownership and cross-functional focus?

- What is the mission of the Process Management Committee (PMC)?

- What are the cross-functional aspects of the process that your job is part of?

- Who is the owner of the process that your job is part of? What is his or her title?

- Why is it important for top management to accept and support the LSS concepts of process ownership and cross-functional focus?

- What is the most common form of process modeling used in your corporation?

- What is most often used as supporting material for that process model?

- What is the difference between process mission and process scope?

- What are the four questions necessary to answer to fully identify the process scope?

- Using the scope statement in Figure 2.5 as a guide, write a mission statement for the accounts receivable process.

- Select a top priority business process activity in which you are directly involved. Write a mission statement for and define the scope of that activity.