CHAPTER 3

Seeking Health

Case Study: Healthwise Decision Aids—Personal Health Decision Support |

|

Elena’s Story: It Can Happen to Anyone

Less than 6 months after her father’s cancer diagnosis, Elena suddenly feels faint and passes out on the couch after the brief exertion of vacuuming the carpet in her living room. She comes to after a couple of minutes, still feeling faintness and lethargy, rapid heartbeat, and heaviness in her legs. She calls Ben and tells him about the occurrence. Her first impulse is to attribute to overwork, being out of shape, the stress of dealing with his condition, and worry about giving enough attention to her daughter.

Elena is reluctant to see a physician after just a single incident. Because nobody was at home to witness the episode, Ben encourages her to see her doctor. Elena realizes her fainting and rapid heart rate may be of concern, but because it hasn’t recurred and there was little pain, she feels she can safely “wait and see.” However, at Ben’s insistence, she calls her primary care physician, Dr. Fran Martin, a general practitioner in a family practice.

A nurse handles the call and asks Elena to describe the incident. The nurse then asks a series of specific questions: Do you have any relevant medical history? What medications are you on? Are you wheezing? Do you have an elevated heart rate? Because the family practice follows a consistent routine for patients calling in with potentially critical issues, the nurse has been trained to use an interactive checklist system following current clinical checklist practices. The checklist serves as an information model for patient intake, so that clinicians in the office are prepared for the possible conditions Elena may present. If it had been an emergency, Elena’s responses to the checklist would have triggered immediate treatment. Because it is not an emergency, the nurse asks Elena to take an appointment for 8:15 the next morning.

Concerned by the urgency of the nurse’s questions, Elena reflects on her episode. She had not thought it significant at first, but she now sees a pattern. She had stopped exercising about a year earlier, hasn’t been watching her diet, and smokes about a pack of cigarettes a week.

After spending hours reviewing information about her father’s condition, Elena is quite familiar with consumer health websites. She runs searches on her symptoms and is quickly overwhelmed by the volume and variety of health sites. Although some top hits seem reliable by virtue of being prominent “brands,” such as Mayo Clinic, WebMD, and Family Doctor, others are offbeat and amateur in appearance.

She finds dozens of links to brief articles on syncope, heart disease, and stress. There are more than 10 different diagnoses she could follow. Although her symptoms seem simple, teasing out a clear condition is impossible. Ironically, the more informed she becomes, the more complex her situation appears to be. The many aspects of her condition (if she even has a condition) are daunting. Elena grows worried and frustrated.![]()

Information First Aid

Although consumers can and will use whatever information they can find online or find easily, mere use does not mean that their problems are being solved. Health information seeking is much more complex than goal-based information seeking. Information seeking presupposes the goal of an answer, which facilitates a real-world action. Health seeking can be a long, continuous journey with an elusive goal. How do health seekers know when their goal of health has been achieved?

Consider Elena’s scenario, which appears to be a simple information-seeking case. As an individual with an emerging health need, she queries the Web in an attempt to understand her situation and determine some possible causes. At this point, the activity revolves around a consumer choice situation, as Elena has not yet been diagnosed by a doctor. Interactions with information (searches leading to websites) are incomplete and inconclusive.

Designers accounting for this “consumer” activity might consider a normal person’s limited knowledge of their situation. Recognize that participants will “not know what they don’t know” by the end of their search. A design scenario can never fully address an end-to-end situation in health, as the individual’s end state is not a predictable outcome—it is unknown and unknowable. Health is also a biological and cultural function; it is not an end result guaranteed by the service provider.

Information seeking is the first intervention most people take when considering their health options and undertaking a course of action. It defines the point at which a person acts on a motive and locates an online (or other) resource. From a user-centered design perspective, information seeking is an activity that breaks down information tasks into specific actions and guides tangible design options in interactive product design.

Do not assume that information seeking represents the core user behavior your interactive design or product is concerned with. Taking action on that information must be assumed, in most cases, to be the outcome. It is easy to overemphasize the significance of information seeking as a central activity. It seems to represent the most salient point of a consumer’s engagement with an information resource or service. If health-seeking behavior is studied only within the scope of a product or service, the risk of confirmation bias increases greatly. That is, we are likely to discover what we are looking for because we have offered users no other choice! How do we evaluate beyond the boundaries of our product scope when information seeking explains the behaviors we observe?

There is no single best UX methodology, but some approaches may fall short. For example, a strong task-oriented design approach may fail to capture and represent the activity system of which information seeking is just a part. A focus on interaction usability may optimize the website interaction and fail to discover missing or ineffective content.

The design and testing of consumer sites and services encounters risks that professional and in-house systems do not have. The primary risk may be called the “home court disadvantage.” An existing system is considered to have a public user base that can be sampled by drawing on local self-selecting participants. A confirmation bias is promoted when interaction design is evaluated with positive outcomes from small samples of nondedicated users. The generic use case may ignore the vital and urgent necessities real people have for information. Yet all the user actions hidden from observation—prior and forgotten searches, family interactions and conversations, encounters with professionals—are inaccessible to a product-focused design orientation. The real life of the health seeker comprises much that cannot be easily reduced to personas and scenarios.

This chapter identifies the stages of activity in a goal-directed journey, scenarios wherein people learn, decide, and take action. Is there a “user” in the conventional sense, as the subscriber to a service or active user of a product? When people are motivated to recover health to restore normal life, their health activities are oriented to health seeking, which describes the persona’s intent and suggests the primary context designers might consider in making product or service design decisions.

Information Is Insufficient

Elena’s scenario points out how real-world problems can show up in one’s lived experience as a jumbled mix of personal concerns—disease symptoms, emotional feelings, the wearing signs of stress, and the cognitive shifts experienced as different information sources are considered. Although information seeking may seem like a rationally guided task to a designer or professional, the felt experience of the person living with a health concern is not experienced rationally. Information-seeking tasks demand a rational mindset, at least to compose effective queries and evaluate results. Yet for health seeking, information seeking is only an aid, and one that is subjugated to the necessity of identifying health options, considering actions, and recovering health.

Health seeking invokes numerous trade-offs, options that may constantly shift depending on how sense is made of their fit to circumstance. A person with employer health benefits might explore all options available to her economic situation. An unemployed individual with no health insurance might attempt to mitigate the near-term effects of the disease process until he has coverage or can afford treatment. Someone else in the early stages of a disease might not be motivated enough to “seek” a healthcare response.

Health is always a relative condition, and there is a wide range of “normal” across the population spectrum. A health concern may be experienced as a bundled emotional mess, as a mix of worry, anger, or confusion; frustration over the lack of knowledge or choice; and the physical pain compounding this emotionality. Or it may be experienced as nothing more than a physical performance problem interfering with one’s plans. Although the emotional response of individuals may vary widely, significant cognitive and emotional overload may be experienced by anyone merely by accomplishing the first of many health-seeking actions. Any one of dozens of personal concerns and habits could tip the balance of action toward a different outcome.

Most human decisions are not as rational as we like to believe. As cognitive scientist Gary Klein has shown, decision making even under optimal conditions is nonrational and emotionally biased.1 Under the stress of health concerns, decision making may be colored significantly by known cognitive biases implicated in information seeking, especially:

• Confirmation bias (seeking and filtering information to support one’s preconceptions).

• Loss aversion (attempting to mitigate perceived losses, inferred from seeking information to learn about or confirm/eliminate severe risks).

• Anchoring (focusing attention on salient points of information rather than considering all relevant views).

• Pessimism or optimism (believing in biased outcomes that may not be probable based on prior attitude).

Individual health decisions are often made as the result of uncertainties, emotional contexts, hopes and fears, and serendipitous conversations. People are not predictable users of systems. They “muddle through,” recruiting information and other helps in ways that uniquely fit their life situations. Human beings are motivated to negotiate and bridge gaps or perceived discontinuities in their access to reality. They have many and shifting priorities, which are redefined in their making sense of a situation as it appears to them, in the context of the other issues in their lives.

Information Seeking as Self-Diagnosis

Health breakdowns are clearly experienced as “gaps” in the continuity of life and represent a motivated occasion for sensemaking. People attempt to understand the impact and options for a health condition on their own (unaided by health providers) by information seeking.

Yet diagnosis is a complex cognitive task learned through experience by consolidating memories over hundreds of cases. Except in trivial instances, health seekers are not likely to reach a correct diagnosis on their own. Even if health seekers do identify their condition correctly, they would be unable to determine the best response given the range of tests and examinations, traditional and emerging treatment options, or possible comorbidities related to other health concerns. Yet people seek information to evaluate their situation and to deal with (not minimize) uncertainty.

Searches on individual symptoms are highly unreliable, because symptoms (awareness of feelings from internal states) and signs (externally presented indications of disease) are just the outward manifestations of an internal process. People act on symptoms, but mistake them for the disease. Guesses are likely to be unproductive at best, dangerous at worst. A general design axiom might be formulated with this precautionary principle* in mind: Expect that people seeking health information will have insufficient knowledge to conclude the information is valid in their case; design accordingly.

Searches aimed at guessing a diagnostic outcome are even more unreliable because individuals cannot run simple tests and take consistent measures without training or calibration of the measures against a standard. People also have insufficient understanding to compare and trade off “differentials” to narrow down and identify the most likely condition from several alternatives that might match symptoms.

If designers know the rationale for health information seeking and recognize that traditional websites can be misleading, what are the best alternatives to consider? This chapter’s case study describes a diagnostic tool using a decision tree mode, which shows that for some conditions and situations, a thoughtful experience design can meet the demands of health seeker’s inquiry with information first aid.

Making Sense of Health Decision Making

Taking care of one’s own health is ultimately a series of decisions to take healthful actions, decisions assisted by medical guidance, trusted information resources, and personal social networks. Decision researchers still debate how people actually make decisions. Some decision theories assume individuals choose the best action according to unchanging and stable preferences and constraints. The classical, rational choice model assumes that humans are rational actors, and that they choose options consistent with anticipated economic interests. Behavioral models are grounded in empirical observations of human decision behavior, and their theories start from observations of decision behavior, revealing decision making as significantly biased and experience-based. Naturalistic models of decision behavior are developed from consistent in situ observations and analysis of the cognitive tasks being performed by the decision process. All three offer value and need to be understood to relate to the different contexts referred to as “decisions” in healthcare. But only the naturalistic model requires that we recalibrate our notion of how decisions are actually made in real life.

The classical model has been debunked at least since Herbert Simon’s explication of bounded rationality.2 Rational choice provides a formulated schema for making the “right” decision when faced with several alternatives. But the model is untenable in reality, failing to account for the cognitive and emotional biases that have a significant influence on choices and actions.

Yet the classical model has been widely implemented in corporate and organizational practices. Kepner-Tregoe and the Analytic Hierarchy Process are two well-structured decision tools that enable people to perform a factor analysis of decision components to facilitate more effective final choices.

What people actually do in practice differs significantly from these best-practice models. Humans consistently make decisions based on an emotional response, a felt understanding of a given option path. In group decisions, emotional persuasion rather than true consensus is the norm. In short, what we call “going with our gut” rules in all types of decisions—personal, business, financial, and health.

The Branching Metaphor of Decision Trees

A venerable decision analysis method—the decision tree—has been taught to healthcare workers for years and is gaining support for individual decisions. Nurses, physicians, and specialists learn to read and memorize “algorithms” or decision structures that visually portray decision options as a series of steps (Figure 3.1). The decision tree approach to structured decision making discussed by science writer Thomas Goetz suggests that decision trees are effective for making better everyday health decisions.3

Decision trees have two problems, however, that reduce their efficacy in health reasoning. First, they are formulated on the assumption that health decisions can be made by assigning inputs and outputs to determine a preferred course of action. Better inputs—food, exercise, lifestyle decisions—lead to better outputs, which are improved health measures and a healthier experience of life. In practice, however, these inputs are a matter of degree, not either/or binary decisions. The extent to which a given action improves health does not show directly as an output.

Second, decision trees by their design are retrospective constructions, not prospective. They are a proposed path of choice based on someone else’s past experience with a similar choice scenario. For a decision about a personal unknown situation, such as choosing between surgery and drug therapy to treat a heart condition, decision makers are faced with a quandary. They are required to enter options for each pathway on the tree’s branches of decision logic based on past data from other people’s situations.

FIGURE 3.1

Decision tree for a health problem.

The goal of decision trees is to empower health seekers to make up their own minds and to be less reliant on their physicians in personal health matters. Yet the physician will have seen and intervened in perhaps hundreds of similar cases, compared to the health seeker’s single (and highly biased) case. The emotional freight attached to each micro-decision in a tree can also bias the application of the tree. A significant role for any physician is to help guide patients to health decisions that are in their best interests. Analytical methods such as the decision tree do not enable the inexperienced health seeker to formulate a decision based on context. As the science of decision making suggests, such a practice is too rational for most individuals.

A key difference in Goetz’s application is using the tree for personalized decisions, so that the option paths are constructed for an individual’s situation. But the form of the tree in most applications is as a clinical guideline that presents a set of rules that can be universally applied. These are similar to clinical algorithms for selecting drugs and dosages, or specifying the correct diagnostic procedure. Devising decision trees as tools for guiding complex health decisions is based on the classical model, and they may fall short as a self-diagnostic tool. Instead, these structured decision support tools might be used as ways to visualize and categorize options so that eventual decisions are based on effective personal research and trade-offs.

The approach is simple, but can be misleading if health seekers attempt to self-diagnose following its steps. The tree tools may not be helpful outside of the context of a diagnosis for which the guidance applies. By the time health seekers receive a clinical diagnosis, they usually have guidance from their physician on the decisions and steps necessary for their individualized situation. A generic decision tree for a disease may present a range of options the physician has already considered and dismissed.

In addition, by the time one gathers and analyzes the information necessary to construct a decision model (or an accurate decision tree), the best path among those options would become obvious because of what was learned in the process, not because the variables were organized in tree form. Important life and health decisions are more complex than input-output relationships. Over time, people change their valuation of different options, which are not balanced evenly on a simple flow diagram. In life, valuation of personal options is tested through a dialogic process (e.g., sensemaking). People speak with others who had similar experiences and judge the same variables in personal terms. Attempts to simplify the process by reducing it to a pathway may help, but may not actually aid in a significant decision. Also, a personal decision is not a simple act performed at a given time; it takes place over a series of smaller decisions. It is a mix of actions and new options that are opened up due to actions taken.

Human beings are notoriously poor at envisioning the future and making good prospective decisions. They are driven by prevailing emotions and fail to consider trends, countervailing evidence, and exceptions. When people face a life decision, they may wish for a certain outcome (e.g., to lose weight or regain a youthful physique), but what they choose on a moment-by-moment basis may contradict the desired outcome. Health choices beneficial in the long term compete with short-term choices that have significant emotional resonance and psychological benefit (e.g., smoking or eating dessert).

Although the decision tree represents a road map of best options, it is a rational model that assumes a rational decision maker. People need more than the motivation of future prospects to maintain a commitment to a personal plan for health recovery. So although decision trees could be used to describe prospective, anticipatory decisions, they are not the best tool for the way people actually reason about the future.

Expert Decisions Are Intuitive

A physician’s experience with numerous cases leads to a decision-making style that appears intuitive. Intuition is not a magical synthesis of ideas or a leap of creative thinking. Intuition is largely based on responses to new configurations that trigger recognition of similar situations from the past. Intuition emerges as personal (tacit) knowledge and can lead to effective pattern matching in a problem-solving situation.

Professional clinical decisions often draw on intuition and demonstrate the problem-solving style of sensemaking. Sensemaking is both retrospective and prospective; it allows for trial, testing, and learning by considering possible narratives in the face of a situation.

Sensemaking (as Gary Klein defines it4) attempts to understand the causes of recent events and anticipates the outcomes that may occur at that time or in the near future. Klein presents the example of a group of anesthesia residents attempting to assess and repair the hidden source of a ventilation tube blockage in a patient simulator. Of 39 trainees, only 9 were able to solve the simulation. In all cases, these “adaptive problem solvers” jumped to an intuitive conclusion about the situation, quickly tested the hypothesis, and kept an open mind.

Sensemaking describes the style of expert problem solving in medical disciplines characterized by evidence-based decision making, although this is only now beginning to be recognized.5 Research in clinical informatics shows that residents and trainees use decision tree approaches for diagnostics and treatment decisions. Trainees do not have sufficient experience to make expert judgments, and they are required by agreement and liability to “go by the book.” Senior physicians, on the other hand, have a huge repertoire of experience to draw on, and do not need to look up decision algorithms for common diagnostics. Because the resident can manage the majority of cases using the standard algorithm, a senior doctor can help with unforeseen and complicated situations that trainees cannot and would not address. If a complex patient situation challenges an expert, would he or she even try to resolve it by using a decision tree? If the problem is not common, it is solved by an unfolding process of discovery, trial, and iteration—sensemaking and not decision making.

We cannot always design for sensemaking because the resources recruited in a problematic occasion are things like memory cues, images, and references that connect to personal gaps. Professionals will not stop and read a student-level guideline in every tough case to catch a rare exception. The exceptions are caught by decision triage. Decision triage simply enlists another knowledge resource (person or system) to mediate in the decision, especially for a complex situation, such as one in which multiple drugs could interact or diseases co-occur. It is also a designable process whereby a second health professional (nurse or physician) relies on a trusted information resource as a check on the decision practice.

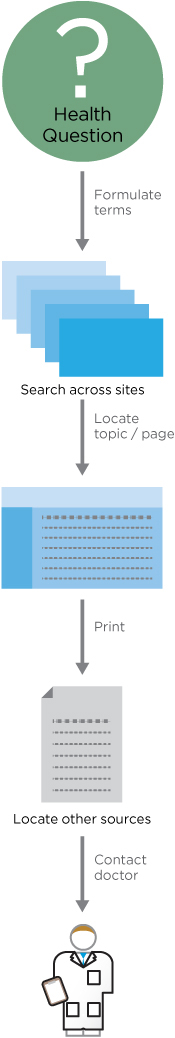

FIGURE 3.2

Health-information-seeking pathway.

Design for Consumer Health Decisions

How well can product or interaction designers understand a consumer’s health-seeking options? Designing for websites or services may be based on very limited research, small samples, and usability studies. Without experience in the healthcare domain, service and information design approaches may “underconceptualize” the problem. Designers often treat online services as equivalent in function and as though an information product that is successful in another domain (such as Mint.com for personal finances) will translate to healthcare applications. Sometimes this works if a concept is presented with good navigation and information architecture principles. But the complexity of health problems and information context suggest otherwise. People do not manage their health like they track investments, and they could not if they wanted to.

Designers creating healthcare scenarios for a service design may be tempted to envision objective, “clinical” perspectives to describe expected health-seeking behaviors. For example, a linear series of events, decisions, and actions may be traced from a person’s information seeking to a service touchpoint (Figure 3.2).

From a health seeker’s perspective, concern for a disease condition drives the journey and leads to contact at the physician’s office. The actual touchpoint is a coordinator or receptionist, triggering an exchange of information. The clinical service process may involve extensive independent preparation for a day’s appointments, allowing the physician to manage a high-volume practice and to maximize patient interaction while satisfying the necessary patient scheduling for emergent situations.

Social Construction of Healthcare Services

What is the requisite “standard of care” for designers in a consumer healthcare context?* How do we know we have helped health seekers? In specifying content and interaction, the respected design values of simplicity, clear communication, and visual and content hierarchies are necessary but insufficient. Healthcare services at every point are designed and guided with respect to health outcomes.

Health content intersects social practices, scientific validity, and current medical knowledge. Accepted practices and both core and referenced knowledge can be changed or overturned abruptly, requiring revision of related health issues in online and archived sources. A good example of currency is the US Centers for Disease Control’s website, a public resource but not (strictly speaking) a consumer context. Consider the precise language and comprehensive categories found on a given page structure (Figure 3.3).

FIGURE 3.3

A public context health information site under the highly usable URL www.cdc.gov/Lyme.

Retail healthcare is no different than retail sales. As an online service grows its user base and market value, new features are launched and evaluated for customer engagement. The content page sprouts multiple lists and navigation areas as the various features (articles, tags and indexes, related content, external resources) compete for attention. UX and design decisions get squeezed between these competing interests in the internal decision-making process for commercial or sponsored websites. For designers, creating realistic end-user scenarios and defending appropriate diversity and user-sensitive information can become political, almost adversarial actions. Although the application of user scenarios is a design process, their construction requires content knowledge, which verges into the claims of core content disciplines (e.g., medical, biological, publishing, product). Arguments to resolve the narrative, validity, and veracity of scenarios are typical among disciplines, often resulting in compromised or mediocre narratives.

Building Up the User Experience Catalog

Intense project schedules (as typical in Agile development) sometimes require the compromise of some design values on behalf of product delivery. Tradeoffs between schedule and quality are frequent in consumer-facing healthcare products; in most cases the designer loses the trade. Of course, user data is needed to win the argument, not merely Web analytics.

UX practitioners have learned to adapt user research and discount usability to support the rapid turnaround required in today’s product development cycles. The primary UX research methodologies—ethnography, interactive interview, usability testing, remote observation—now have official rapid versions documented in the literature.

Within healthcare disciplines, however, the rapid mindset is not highly valued. Rapid research can be perceived as unreliable and not evidence-based. The health sciences research tradition recognizes rigor, and requires the ability to publish findings in the public research literature. The original UX field of human factors psychology established scientific norms and experimental methods for hypothesis testing and evaluation that remain the standard in healthcare. Healthcare processes, medical devices, control and dispensing devices, and internal information systems are validated by human factors research. Designers in the human factors tradition rely on strong empirical methods, validated measures, and statistical analysis to support high-reliability and safety values in design decisions. Human factors methods are consistent with producing the types of evidence deemed valid for healthcare decisions in current institutional and scientific practice.

These are appropriate methods in the contexts of clinical research, and due to their general acceptance in medical contexts, these hard empirical methods and the presentation of statistical data have become mandated in most clinical situations, including informatics. If lives or significant investments are at stake, industrial-strength human factors experiments and validations are necessary. However, these methods are typically summative, applied after innovation and in an evaluation context, and are better for validation and hypothesis testing than for generative or conceptual design of new informatics concepts or clinical services.

In UX and service design for healthcare applications, we readily adapt standard methods from the UX toolkit. These include observational and interpretive methods, which may be untested or even untrusted in health institutions. Yet these methods may be necessary for a robust innovation strategy and can be defended in terms of their near universal applicability in information product design.

DESIGN BEST PRACTICES

• A newly acquired illness or injury is a novel experience (in most cases). Expect all health seekers to be uncertain in their knowledge, options, and decisions.

• Health seekers may only rarely interact with your product, so rapid comprehension is vital.

• Do not presume people know what they are looking for in a healthcare situation. There are design trade-offs between providing a clear pathway to an answer or multiple options (which can be confusing).

• Design information to help health seekers meet well-defined information needs. Describe these need states with task-oriented labels that relate to the needs and possible decision outcomes.

• Clearly indicate the end result of your service or process so that people know when value satisfaction has been acquired.

• In activity design, help people make health decisions by indicating steps or status in a series or timeline, provide references to related information, and when possible, link to a variety of cases illustrating a range of options a health seeker may want to know about.

Case Study: Healthwise Decision Aids—Personal Health Decision Support

Healthwise is a US-based nonprofit organization specializing in complete information solutions for healthcare, which the company refers to as “information therapy.” Healthwise provides decision aids and custom content to hospitals, health management companies, and health websites. It also serves clinicians—nurses, doctors, and health coaches in a variety of settings—who can adapt content provided by Healthwise to “prescribe” this information to a patient or health plan member. Healthwise specializes in providing current, scientific, evidence-based information to the point of user need, using innovative channels and interactive formats.

Healthwise has been in business for more than 30 years, but their focus on improving the user experience of information products is much more recent. In just 5 years, a 15-person UX team has grown to include interaction, visual, and production designers with a range of specialized skills (usability, information architecture, medical illustration, and multimedia art and production). Healthwise interaction designers recently partnered with Indi Young, author of Mental Models 6 and co-founder of Adaptive Path, to establish a mental model methodology in the organization. Healthwise works closely with leading decision support researchers from both the International Patient Decision Aid Standards (IPDAS) group and Ottawa Hospital Research Institute to help ensure IPDAS decision aid standards are met. The Healthwise UX team reports that their methods for understanding users include continual user testing, user interviews, observational field studies, and focus groups. They have developed analysis methods based on card sorting and mental models for representing and mapping decision patterns for interactive aids. Unlike many other information providers, Healthwise maintains an in-house clinical advisory team, and staff work closely with behavioral health psychologists and doctors to review and advise on clinical content and prototypes.

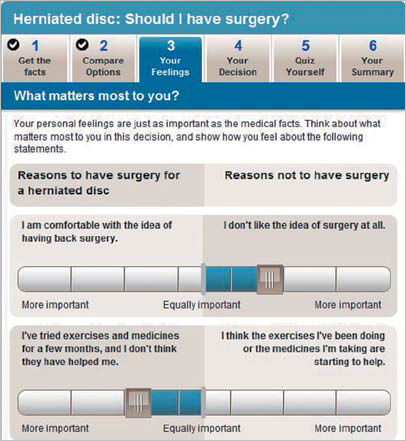

Healthwise Decision Point

The Decision Point resource is an embedded decision aid created for a wide range of conditions. The example in Figure 3.4 shows an individual’s decision steps to proceed with surgery when faced with a herniated disc and its attendant daily pain.

Becky Reed, UX interaction design manager at Healthwise, described the evolution of the Decision Point tool:

The previous version of this [tool] was a hypertext system that was very much in a physician’s mental model. It looks very much like you would see in a nursing protocol book that over the years would be filled with lots of supporting information. We redesigned these with the goal of being able to assess symptoms, and there are two different users conducting this: one user on a health portal trying to figure out what they should do about their symptoms and the other a nurse in a call center talking to a patient.7

FIGURE 3.4

The Healthwise Decision Point decision aid.

Healthwise designed the consumer and clinician tools in parallel because, according to the designers, they have the same clinical logic behind them. The consumer information model was adjusted slightly to emphasize the simpler language and steps. Reed discovered early in usability testing that consumers often misperceive symptoms. For example, people often assume that a tightening in the arm requires an emergency visit. Reed wanted to make sure sufficient education went along with the tool to help consumers interpret the severity of their symptoms correctly: “The intent was to make this tool action-oriented so that the person knows the next step [he or she] should take to better control . . . or resolve the situation.”8

Although the underlying content is essentially the same, the clinical version employs rapid interaction design for nurses and triage coordinators, who can use the tool during a phone call to assess and guide patients. Clinicians use these decisions aids not for informative purposes, but rather as active guides, checklists, and language support, so that they have specific language at their disposal without having to translate for each patient in phone calls. “From a clinician’s point of view, the symptom topic tool allows nurses to use it as a support tool so that they are able to give consistent recommendations. Nurses are highly trained users, so they would be using this tool to make sure they are delivering consistent care,” Reed explained.9

For a related project, the Symptom Triage tool (Figure 3.5), the Healthwise UX team conducted contextual inquiry interviews with floor nurses at clinical sites, and also interviewed representative nurses who worked in call centers and were using competitive products or traditional paper-based nursing protocols for triaging clinical situations. A significant period of user research led to prototypes and revisions, then evaluations of the tool on client websites. Reed continued,

We noticed that [nurses] had a good sense of the types of questions that should come up, but the order of which is often debated. It was important they proactively get a sense of what was coming up in the triage. And then, finally, we knew that nurses are working against the clock, with time being a huge issue. Call time, wait time in discovery, and system time, like scrolling and waiting for windows to start, were completely unacceptable because they contribute to call time and increased cognitive load for nurses. So we addressed these issues with this model. With progressive disclosure, they are able to see the questions that are coming, so they have reassurance that the question they were thinking of has already been afforded in the design.10

FIGURE 3.5

The Healthwise Symptom Triage decision flow.

To strengthen their method and approach, Healthwise staff are returning to the user sites to gather outcomes data and perform additional task analysis to inform design of related applications in overall symptom triage.

The latest direction of Healthwise UX design involves engaging users in interactive dialogue. The Ix Conversation multimedia product uses a virtual coaching methodology to help people understand health conditions. Through branching logic questions, Ix Conversation helps people find the best answers and next steps. In turn, health seekers/consumers are encouraged to seek better targeted or appropriate care from their physicians.

The development of a more personalized approach to health content with a focus on user experience and better design requires significant organizational investment. Julie Cabinaw, Healthwise’s former director of user experience, described the critical role of organizational support and investment in design research in enhancing their competitive advantage through usable and engaging services:

Good design is so critical to user engagement and usage. We can create the best content in the world, but if users can’t or won’t use it or read it, we have not fulfilled our mission to help people make better health decisions. We consider our investment in design extremely strategic for Healthwise.11

LESSONS LEARNED

• Healthcare information can be leveraged into multiple products, serve several constituencies, and increase the opportunities for revenue and brand recognition.

• Insightful product research requires a holistic outlook to identify possible opportunities that would be missed by following a project plan to the letter.

• Get out and play! Early stage field research, on-site and with truly representative people, leads to insights or iterations that guide design, messaging, product plans, or strategy.

• Small-sample interviews and observations can be conducted to acquire “early warning signals” to identify emerging or overlooked needs for public and consumer uses.

• Rapid research and task-oriented usability evaluation may not be sufficient for product teams to identify and develop the right response for needs discovered through cycles of research and iterative refinement.

Methods: Empathic and Values Design

Empathic design research methods are selected for understanding the everyday life contexts of people. Though based on user-centered design traditions, empathic design inquires further into lived experience, with the aim of understanding the authentic perspective of people.

Service and product designers research the experience of individual health and information seeking from a mediated distance, often at best through field research or recruited interviews. In the consumer context (typically Web and interactive digital design), interpretive methods from UX research have currency in gaining user understanding. Perhaps because lives are not at stake in website design, a commitment to business and design performance outweighs validity or scientific values. Partly because hybrid, mixed methods are now used frequently, design research has become more applied and informal.

Complexity Demands Interpretive Research

Several years ago, strongly interpretive, empathic, and even ethnographic methods were considered too “soft” for business decision making. In clinical and professional contexts, empirical methods (measured observations in controlled settings) are well respected. A commitment to evidence-based practice is often expected in institutional research, requiring adherence to a medical definition of evidence as verifiable objective observations in a controlled setting. Though we might argue the validity of human and social forms of evidence, the healthcare environment expects careful sampling, control for variation, structured data collection, and quantitative if not statistical analysis of data.

Medical, nursing, and administrative practices and procedures converge at the point of patient care, and these perspectives may conflict on many issues. When empirical, evidence-based approaches are fully adopted in institutional culture and reasoning, complementary perspectives are screened out, and the patient’s perspective is filtered out as well. Empirical studies that measure the outputs (such as outcomes, length of stay, and satisfaction) ignore multiple and unknown input variables (such as prehistory, unique conditions, and cultural or individual differences). Although necessary for high-confidence decisions affecting populations, such as randomized clinical drug trials, empirical and experimental studies are not intended or useful for design and interaction decisions. Narrowly scoped, isolated variables in such studies cannot reveal the emerging patterns at the heart of the complex situations across the spectrum of personal and institutional care.

However, in the consumer context we have more freedom of research design. We can first recognize that people’s experiences and meaning as consumers in healthcare, in personal health, and in caregiver relationships are forms of personal knowledge. Experience has direct meaning for individuals, and in empathic design research we can elicit and represent meaning veridically—as true to their experience.

Interpretive UX methods are tools for engaging design research participants in creative, subjective expression of their understanding. These methods are biased toward eliciting individual experience, the projection of creative ideas, or subjective narrative expression to better understand and empathize with the varieties of human experience or to formulate creative ideas in early innovation.

Focus groups and in-depth interviews are not typically interpretive. Group interpretive methods are often generative, not directly eliciting individual expression but deriving it from creative artifacts. Design-led workshops are conducted to co-create images and artifacts in a semistructured setting, allowing for individual expression while engaging participants in a novel group exercise. Co-creative techniques for consumer-oriented research include:

• Facilitated group processes for eliciting ideas and generating proposals.

• Storytelling and narrative techniques.

• Embodied methods for acting out scenarios with low-fidelity mockups or concepts.

• Individual projective techniques (such as collaging or sketch imagery) for subjective expression.

In the early stages of design, identifying the right problem context calls for patience and tolerance for ambiguity. It is called a “fuzzy situation” for a reason—the initial situation is perceived as complex, and problems may be described by stakeholders in terms of deficiency rather than opportunity.

When we are not immediately sure of the best solution or intervention, UX methods are more readily employed and more effective than experimental methods that require a hypothesis and statistical sampling. Dealing with complexity calls for us to carry out multiple observations and iterations, not experiments with premature hypotheses and unknowable constraints. Rather than avoiding human complexity, interpretive research helps identify the scope, boundaries, people, practices, barriers, and opportunities in the situation. They are meant to help understanding, not prediction and control.

Intuition and Insight

An insight is a penetrating observation about a situation. In design research, an insight is an actionable interpretation; it reveals understanding and relates an observation to a design decision. The right observation in context can make the difference between a great user experience and a poor showing in the marketplace.

Insights are claims drawn from the analysis of research data. They may appear intuitive, but are selections of salient observations associated and framed by other relationships in the study. Although intuition can help frame the construction of insights, intuition is not a magical synthesis of ideas or a leap of creative thinking,

Rather than a mysterious personal capability, intuition draws from a person’s largely tacit repertoire of experience and patterns from which to match a current situation. It is the result of experience and reflection on experience in a given domain. In other words, people with healthcare, patient, and industry experience are likely to have better “intuitions” about health seekers than designers without experience in the domain. But designers might have better intuitions about the practical approaches that might be formulated to design and present the solution.

Powerful insights are also produced from iterative working theory. Simple theories, or working hypotheses for understanding, are categories with a guiding proposition that direct observations toward meaningful features. A working theory is not a hunch (although hunches may help). It is an explicit proposal that can be applied by others to test their own observations.

For example, a working theory for field testing a clinical information concept was that mobile applications would find limited adoption in hospital settings for in-depth clinical decision support. Even though most hospital-based clinicians have mobile devices or smartphones by now, their use in clinical settings has been limited by the legibility of text, images, and tabular information. With the prevalence of desktop computers in hospitals, doctors and nurses recognize that the shorter amount of time spent reviewing information on a larger screen outweighs the benefits of handheld convenience. The insight drawn from the data was not just that this claim was supported (in more than 90% of the observations), but that some types of content (images and figures, rather than long text passages) would be used on mobile devices if they were specifically designed for the point-of-care context. Although not a universal finding across applications, the realization allowed product managers to adjust their innovation strategy to focus on current adoption trends and not to overextend resources to accommodate a very small (and nonpaying) market position in mobile technology.

Empathic Design Research

Empathic design comprises a point of view and a methodology, a collection of interpretive methods applicable to human-centered design and research. Empathy is consistent with the innovation theory of designing products from knowledge gained by deeply understanding consumer behavior and aspirations. Harvard’s Dorothy Leonard first gave shape to this innovation theory in an influential Harvard Business Review article, which promoted highly qualitative, open-ended empathic research for understanding real customers and their concerns.12 Empathic design was proposed as first-person research to discover real behaviors in the field, as opposed to hypothesizing through questions in survey research. Empathic design helps designers create a common understanding of the person for which an innovation is planned. Empathic research ranges from first-person methods (e.g., simulating the user or donning impairments to experience aging or weight factors) to participatory design, inclusive design, and ethnography.

Empathic methods seek to understand an individual’s authentic experience in a real-world context, so that design options for enhancing experience or resolving difficulties might be located and attempted. A study by Froukje Sleeswijk Visser of Holland’s Delft University of Technology reviewed the psychology of empathy and described four phases of engagement with participants:

- Discovery: establishing initial encounters with participants, usually targeting a specific user segment, and selecting situations to engage with curiosity

- Immersion: expanding knowledge of and appreciation for a person’s situation and life by participating, hanging around, and absorbing information without judgment

- Connection: making an emotional connection by relating to one’s own experiences, forming associations with situations in the participant’s life, and understanding both feelings and meanings

- Detachment: detaching, reflecting on insights, and applying them to ideation13

Of these four phases, the most crucial to learning and meaningful ideation is immersion, wherein the designer takes significant time to “wander around in and be surprised by various aspects of the user’s world.”14 The immersion period enables the designer or researcher to identify with the everyday life and objects, the tempo and pressures, and the conversations and language of the person being shadowed. Sleeswijk Visser is correct in noting that the opportunity to “hang out” is usually given insufficient emphasis in design projects with tight schedules and budgets.

The Role of Personas

Personas present concise snapshots of representative users or constituents in a design project. Typically, personas are drawn up to match the characteristics sought in the primary participants in a research sampling frame. In consumer projects, user profiles are often generalized to different customer types and are frequently exemplars associated with market segments defined by a business team. In informatics research, personas might be defined for specific professional roles and contexts that determine different levels of expertise, information need, content, or usage patterns.

In a consumer context, an online product or service may be public and fully accessible to all. A full range of health seekers for which a service is being designed may be impossible to characterize, and attempts to project preferred “example user personas” may institutionalize certain expectations. De facto personas (and scenarios) might overemphasize the role of health seekers as users.

Personas are ubiquitous artifacts in the business applications of UX research, and are often presented in flattened, stereotypical ways when invented from representations that have no basis in field research. Ethnographer Steve Portigal advocates for the use of stories instead of stereotyped personas. He makes the case that reliance on personas can create a false intimacy and pretense of user knowledge, preventing the organization from really looking at its customers and considering the reality of their behavior:

Any process based in falsehood takes you away from being genuine. If this is the best way we have to keep the organization focused on a “real” customer, then we have larger organizational problems that need to be addressed. With personas, we’re going down the wrong path. Rather than create distancing caricatures, tell stories. Don’t deny the need to do in-person research with real people. Look for ways to represent what you’ve learned in a way that maintains the messiness of actual human beings. And understand that no tool, no method, and no shortcut, can substitute for real, in-person interactions. People are too wonderfully complicated to be reduced to plastic toys.15

In the best cases, personas are prepared as an outcome of ethnographic research as a tool for presenting and describing salient characteristics of people and their behaviors and interests relevant to a product. However, especially in online consumer healthcare services, access to real patients can be difficult due to privacy issues and the expense of recruiting even small samples for field research. Design teams therefore often make up semi-realistic personas that are adopted as proxies for user research. When proxy personas are adopted by a product team, their limitations may be overlooked and the personas may travel beyond the original utility of standing in for real customer research.

Personas are given context and depth when supported by descriptive stories or narratives, which can be created to follow one of several formats:

• Narrative scenarios involving the personas (similar to Elena’s scenario in this book).

• Rich picture scenarios that illustrate the persona’s relationship to functions in use cases.

• Story narratives that bring the persona to life by presenting an authentic narrative based on real interview data, making the persona an indisputably real person.

Stories based on observed experiences present the most compelling warrants for design decisions because they portray vivid emotions and details that help people remember the salient issues in the research.

Storytelling Personas

Stories (all stories) embody a particular shortcoming that personas overcome—stories are nontransferable in their original richness as a performed narrative. Ethnographers are trained (and often talented) storytellers. They become steeped in interview and contextual data so that their stories are embodied artifacts and part of an overall compelling narrative. This unfair advantage of the ethnographic researcher is not conferred to the product team receiving the stories. When the team tells the same story to management, much may be lost in the translation because team members will not have been immersed in the collection of the field data and will not be trained in the expression of story narratives. Organizational recipients of the research products are better able to work with a set of succinct capsule profiles (i.e., personas) that reflect a composite of salient characteristics of customers (based on real people where possible).

A central problem in human factors psychology is that of identifying and representing a valid range of behavioral and physical (anthropometric) characteristics in the target population. Human factors shows us that designing for the “average person” actually designs for nobody. In healthcare situations, the range of consumers (and patients) is considered extremely diverse. Designing for the average user is not only futile, but impossible. Ranges of characteristics based on relevant distinctions can be used to articulate user profiles. If presenting a range of ages, they can be marked by life stage rather than chronological age or decade. If documenting a range of patients based on type of disease, their touchpoints with the clinical care system (initial presentation, diagnosis, admission, treatment) might be the defining order.

Values Design and Research

A values framework affords insight into essential needs and drivers that motivate emotional and felt responses from people. Psychologist Abraham Maslow’s hierarchy of needs provides a guideline to mapping meanings to observations (Figure 3.6). Maslow’s well-known framework offers a hierarchical formation of values, where underlying physiological concerns (e.g., health) must be resolved before basic safety and social needs can be fulfilled, all in the pursuit of betterment or self-actualization.16

FIGURE 3.6

Maslow’s hierarchy of needs.

Farther Reaches of Empathy

Critics have often missed the essential role of the Maslow hierarchy.* The model describes the normative development of healthy personality, a road map of values for the formation of a strong center to guide life decisions. Whether it is “true” or not is irrelevant. A working theory must first be useful. In an interpretive research context, if the framework is defined and supported by precedent, and if the content it elicits builds understanding and provides insight, it shows sufficient strength for the purpose.

Value-based empathic insights provide a scale to identify a point of intervention for a human concern, starting with the level of needs most important to a participant and the research purpose. Maslow’s hierarchy allows us to identify a position and trajectory from fundamental personal care to self-transcendent values. Though the pyramid form suggests a structural perspective that ends with self-development, a healthy person may be actively meeting needs at any or all levels, as well as seeking self-actualization, at any time throughout life.

Basic health needs are met at the base, but healthcare experience research should explore health seeking at all levels. The hierarchy levels are also “units of analysis,” and clinical research typically focuses inquiry and analysis on solving a problem defined within a scope at one level. Table 3.1 lists empathic design methods that can be selected at each level to inquire into and understand the human needs of a situation. Mapping methods to needs to human values enables the design team to formulate a clear rationale and create a robust case for their research approach.

Any of these methods appropriate for the purpose might be chosen and used in concert with other techniques. The design context—service, website, interior/environment—determines the frame for inquiry and the staging of a series of engagements in the field or online. Any method will be integrated within a design process of iterations, prototypes, and critiques, usually contributing to another phase. An example of a process for redesigning a visiting home health service might include the following:

• Customer profiles and segmentation: Initial sampling frames and categories of clients are used to characterize the primary groups of clients in the service area. Initial (nongrounded) personas and scenarios are created.

• Home audits: Physical audits using checklists and observations are conducted to characterize the living situations and unique needs and requirements in the customer segments.

• Customer understanding: Interviews for physiological and safety needs are conducted using observation frames, checklists, and photographs to characterize the range of people and their needs by segment.

• Service system mapping: To determine the most appropriate new service functions and to maintain the best of existing service processes, initial specifications of service processes are generated as a series of interactions with clients, with differing stakeholders and services by class of service, location, or segment.

• Health experience understanding: To characterize the aspirations and health needs for a range of clients and the service interactions, in-depth interviews are conducted, and observational and empathic methods (such as ethnography and diary studies) are used to understand current and evolving behaviors, trends, and aspirations.

TABLE 3.1 RESEARCH METHODS BY NEED/VALUE

Human need |

Values inquiry |

Empathic design research methods |

1. Physiological |

How and where do participants live? |

Interviews |

2. Safety and security |

What are the probable safety hazards? |

Observations |

3. Social belonging |

What groups and communities are people engaged in? |

Scenarios, storyboarding |

4. Self-esteem |

How do people experience their sense of total health? |

Sensemaking interviews |

5. Self-actualization |

How do people frame and express their highest ideals? |

Generative design research |

A selection of methods can be chosen to research empathically at each level. Questions (and related research methods, such as interview and observation) are chosen for the situation, not from a template. Needs and values are chosen for the insight they contribute in design.

Empathic research requires access to people matching the profiles in a population sample’s range. In consumer health products, a team is often limited in its ability to reach authentic participants. We often have to make do with reasonable estimates of experience.

TIPS ON TECHNIQUES

• Access to real patients is rare. Academic researchers and clinicians require ethics board approvals to conduct even informal research with patients. Researchers rely on proxies for real patients as needed, who can be recruited for nonclinical design research and product evaluations.

• If collecting multiple forms of data in a research interview, establish safety and comfort with the participant. Ask permission (and use informed consent and releases when appropriate) if taking photographs or video. Some people may prefer that only manual notes are taken if discussing personally sensitive issues.

• Find additional time to observe and hang around the locations where interviews are scheduled. Additional and unexpected insights emerge from making connections between the interview content and observations in the field.

• Empathic research can be presented in formal or creative artifacts. Before conducting empathic research, identify the expected outcomes or artifacts to communicate the findings to the team. A client may have expectations for traditional personas in document form, whereas a design studio may prefer to co-create new presentations from photographs, interview snippets, sketches, and symbolic maps.