Lock-In

Forcing loyalty with high switching costs

The pattern

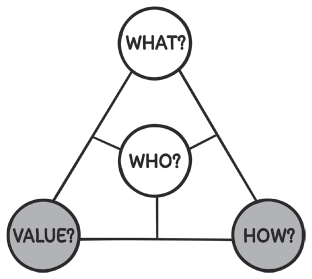

In this business model, customers are ‘locked in’ to a vendor’s world of products and services in such a way that changing to another provider would incur substantial costs or penalties. It should be noted that, in this context, the term ‘costs’ does not refer to monetary costs alone: the time needed to switch to a new option and learn how to use it may be just as relevant for some customers.

Customers can be tied down to a company through various means. They may, for instance, have to invest in new technologies such as a new operating system, or may be obliged to work with a particular insurance salesperson who has been serving them for a long time and knows them intimately (HOW?). The principal concern for the vendor is to prevent any interoperability between himself and the competition in order to keep customers dependent on the company, brand or supplier, thus actively strengthening customer loyalty and promoting future repeat purchases (VALUE?).

Due to the past purchases of the customer, future decisions and flexibility will be constrained. Although familiar with switching costs, companies generally find managing and evaluating them accurately very difficult. In order to convince customers to still purchase products, the Lock-In concept can be combined with other schemes such as the Razor and Blade model (#39).

The Lock-In pattern exhibits a number of different variations. Contracts mandating the use of a particular supplier, for example, are a fairly obvious version of the pattern (HOW?). Another, very common, form is invested assets that require specific follow-up purchases (HOW?). Such dependency is frequently established by means of technological restrictions such as compatibility or even patents. The latter may play an essential part in the Lock-In concept (HOW?). Ties can be created through the mere act of purchasing additional accessory products from a manufacturer, since customers will not be able to recoup past investments should they want to switch. Again, considerable switching costs can result from required training and classes offered by a specific provider (HOW?).

The origins

Because of the large number of its variations, it is difficult to trace the origin of the Lock-In pattern. Contracts stipulating legally binding obligations were regularly negotiated and recorded in the Roman Empire as far back as the 6th century. Other Lock-In variants such as training requirements or technical mechanisms have also presumably been around for a long time.

The complex technological advancements and increasing use of patents over the past hundred years or so have greatly favoured the rise of Lock-In business models. In the computer and software industries, in particular, this concept has gained favour through the technological developments that have emerged since the end of the 19th century.

The innovators

Gillette, the American manufacturer of safety razors and personal care products and creator of the disposable safety razor, was one of the first firms to employ a Lock-In business model successfully. Its first razors with disposable blades were sold in 1904. In line with the principle of this system, only Gillette’s disposable blades match the handles. Customers are obliged to purchase Gillette-brand blades, which carry a higher margin. Control is reinforced by a number of patents that prevent other companies from entering this market with accessory products. The disposable razor blades (consumables) generate recurring revenue with high margins and offset any losses incurred by the initial low-priced offer of the handle.

LEGO is a Danish manufacturer of a small, brick-based toy system comprising interlocking parts. LEGO adopted the Lock-In business model by designing its products and accessories to work only with other compatible components of the patented design. Since it is not possible to combine LEGO’s parts with those of its competitors, customers must purchase LEGO-compatible products, thus increasing customer retention and revenue for the company.

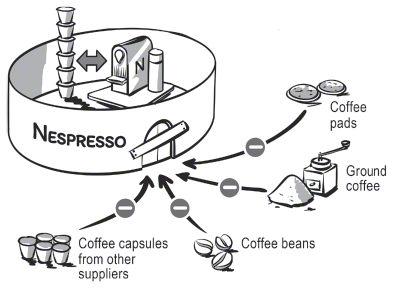

Nestlé is a past master in the implementation of the Lock-In pattern. Its Nespresso system was invented by a Nestlé employee in 1976. It consisted of a coffee machine and patented coffee capsules, which were sold separately by Nestlé. Customers were obliged to continue purchasing coffee capsules from Nestlé on account of the technological specifications of their coffee machine. Switching to another system rendered that customer’s current machine obsolete, leading to the obligation to purchase a new series. The Lock-In business model can often be usefully supported by appropriate product innovations: Nestlé found that one of the major threats to customer loyalty was if its coffee machines broke down. The critical element influencing the lifespan of Nespresso’s machines was the gaskets built into the machines themselves. Nowadays gaskets are fitted within the capsules rather than the machines, in order to lengthen the latter’s lifespan and at the same time delay customers’ decisions to update their systems – another Nespresso or a competing machine. While rather more expensive than fitting the gasket into the machine, this solution significantly extends the lifespan of the machine and consequently improves the Lock-In effect. In recent years, Nespresso has lost several legal proceedings to uphold the exclusive right to commercialise capsules compatible with Nespresso machines. Thus, several competitors have started to sell alternative coffee capsules that can also be used in Nespresso machines. Interestingly, Nespresso is still able to achieve Lock-In effects with its original capsules due to the strong brand relationship that has been built up with customers over the years. Nevertheless, in 2014 Nespresso launched a new machine with an exclusive capsule fit. Using QR codes, the machine identifies each capsule to provide optimal parametrisation of the coffee preparation process (pressure, temperature, time). This creates customer value and leads to Lock-In as a side effect.

Another company that thrives using the Lock-In pattern is Apple. Apple ties its users to the brand by implementing a common operating system on its devices and connecting them via iCloud. This not only enables users to seamlessly share media across Apple devices, but by making synchronisations to third-party systems such as Android rather inconvenient, this increases the costs of switching to non-Apple devices. Many other features, such as Apple TV’s Airplay (which allows music or videos from iPhones or iPads to be effortlessly shared over Wi-Fi), enhance customers’ incentives to stay or even expand within the Apple ecosystem.

Lock-In: Nespresso

When and how to apply Lock-In

‘Keeping existing customers is cheaper than creating new ones.’ This old marketing adage is the basis of the Lock-In pattern. You can implement Lock-In in three different ways. First, legally, by writing contracts with tough termination clauses; this is probably the most obviously off-putting Lock-In mechanism for customers, making it somewhat short-sighted. Second, technologically, by creating product- or process-based Lock-In effects, preventing customers from easily switching to different suppliers or providers; this often goes hand in hand with maintenance activities. Third, economically, by creating strong incentives that make customers think twice before changing their supplier or provider. Financial rewards for cumulative purchases made is a popular Lock-In method, but more sophisticated mechanisms can be created by combining Lock-In with patterns such as Razor and Blade (#39) or Flat Rate (#15).

In order for a Lock-In strategy to be affected successfully, a number of factors need to be borne in mind. One important aspect is the commercial shelf-life of a product, as switching costs become lower the shorter this is. Other criteria to be considered are the ability to resell a product or to offer a range of additional products. Whether it makes sense to do so is, in turn, dependent on how many suppliers are willing and able to offer such products.

Some questions to ask

- Do we have legal, technological or economic means by which to retain our customers?

- Can we successfully implement the Lock-In pattern without damaging our reputation and losing potential customers?

- What soft and indirect mechanisms can we use to lock our customers in – for example, creating additional customer value?