Hidden Revenue

Seeking alternative sources

The pattern

In the Hidden Revenue pattern, the logic that a business has to rely exclusively on the sale of products or services is abandoned. Instead, the primary source of revenue is derived from a third party, who cross-finances the attractive free or low-priced offerings made to customers (WHAT?, HOW?, VALUE?). A common application of this model is to integrate advertisements into the offering, thereby attracting customers to the advertisers who fund it (WHO?). The chief advantage of working with the Hidden Revenue pattern is that it accesses an alternative source of income that can supplement or even wholly replace the revenues generated by the conventional sale of products (WHAT?, VALUE?). Obtaining financing through advertising may also have a positive impact on the original value proposition. Generally, many customers will be willing to watch a few ads if this means that they get a better deal on your goods or services (WHAT?).

The origins

While it appears that the ancient Egyptians had already resorted to advertising, the practice of using ad sales as a main source of revenue is a more recent development. The first instances of ad-based funding can probably be traced back to the bulletins that began to be distributed early in the 17th century with the development of the printing press. These typically contained public announcements, court hearing schedules, obituaries, as well as paid private and commercial classifieds. The classifieds business was so lucrative that most bulletins were financed almost entirely by it. The modern intrusive version of these bulletins is the ad flyers we all receive through our letterboxes and on our computers today.

The innovators

Over time, a range of other exciting and innovative business models have been created based on ad-funded Hidden Revenue. JCDecaux, founded in 1964, is an excellent example. The company delivers innovative advertising systems for public ‘street furniture’, including bus shelters, self-service bicycles, electronic message boards, automatic public toilets and newspaper stands. JCDecaux works with city authorities and public transport operators to provide such ‘street furniture’ for free, or at a reduced price, in return for exclusive advertising rights. Advertisers pay JCDecaux for prime locations and transit media opportunities, while the cities benefit from the free or cheaper public services and advertising design innovations, with JCDecaux serving as intermediary between the two parties. In the case of the self-service bicycle scheme Cyclocity, further revenue is achieved from hire and subscription charges. The result is happy users of the bicycle rental service, less motor traffic in the cities and effective advertising for local businesses. The Hidden Revenue model generates annual revenues of over €2 billion for JCDecaux, making it the largest outdoor advertising corporation in the world.

Another type of innovation based on Hidden Revenue is free daily newspapers. Financed entirely through advertising, these free dailies generally achieve a very high circulation, which in turn has a positive impact on advertising rates. Media company Metro International is a pioneer in this area. Its eponymous free daily newspaper is one of the most frequently read papers in the world. The first edition of Metro was distributed in 1995 in Stockholm, and today it is distributed in more than 20 country editions, reaching some 35 million readers a week.

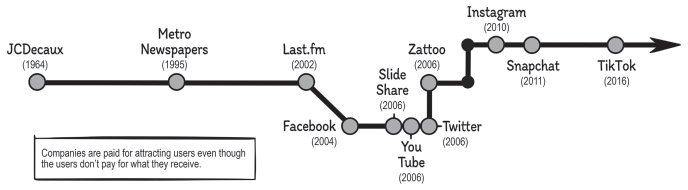

Hidden Revenue: timeline

‘Targeted advertising’ is a special version of Hidden Revenue adapted to the Internet. Ads are adjusted to specific target groups to avoid waste coverage and to communicate the advertising content efficiently. Google has very successfully implemented Hidden Revenue in this novel form. Originally founded purely as a search engine for the Internet in 1998, Google now dominates the search engine market with a number of free services including web search engines, personal calendars, email services and maps, as well as specialising in other Internet technologies such as cloud computing and software. With all this, Google has become one of the biggest brokers in the online advertising business. The company is able to maintain its register of free services by cross-financing through its Google Ads advertisement programme, which allows companies to purchase targeted advertisements that then appear on Google’s search listings depending on the search terms entered by the user. Google receives revenue on a cost-per-impression (i.e. each time an ad is displayed) or cost-per-click (each time a user clicks on an ad) basis. With this scheme, the company attracts more customers and this in turn increases advertisement revenues. Google’s business model allows it to generate billions of dollars in revenues every year and to maintain an online advertising market share of over 35 per cent. Many other businesses, in particular social media platforms such as Instagram, Snapchat and TikTok, have started to rely on targeted advertising as their main revenue streams.

When and how to apply Hidden Revenue

This pattern’s potential was systematically overvalued throughout the early years of the new economy: countless companies were valued highly but failed to generate any real revenues. Hidden Revenue is still hard to assess today. Just think of Facebook paying a staggering US $16 billion for the WhatsApp messaging service. At the same time, customers have become increasingly wary of Hidden Revenue. In Germany, where consumers are known to be especially concerned about sensitive data being misappropriated, every third WhatsApp user considered leaving the service upon hearing about the deal with Facebook. At the same time, Hidden Revenue continues to be extremely popular in advertising and customer data trading.

Some questions to ask

- Can we separate customers from revenue streams?

- Can we commercialise our assets by other means?

- Will we be able to keep our existing business relations and customers even if we tap into additional Hidden Revenue streams?