Add-On

Additional charge for extras

The pattern

In the Add-On business model, while the core offering is priced competitively, numerous extras drive up the final price. In the end, customers pay more than originally anticipated, but benefit from selecting options that meet their specific needs. Airline tickets are a well-known example: customers pay a low price for a basic ticket, but the overall cost is increased by ‘add-on’ extras such as credit card fees, food and baggage charges.

The Add-On pattern generally requires a very sophisticated pricing strategy. The core product must be effectively advertised and is often offered at very low rates. Online platforms support this kind of pricing strategy since they allow customers to compare (basic) prices. Skyscanner compares cheap flights for example, while other services are available to compare the price of hotels, car rentals, vacations and more. Such hard price competition promotes a winner-takes-it-all philosophy.

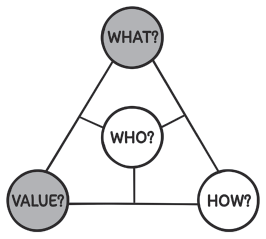

As described, customers pay a hefty premium for extra features (VALUE?), which may cover anything from additional attributes, accompanying services, product extensions or even individual customisation of the product. It’s up to customers to decide whether they want to spend additional money on add-ons or whether they will settle for the initial basic value proposition. This is where they can derive benefit from the Add-On pattern, being free to choose whether they want to customise their product according to their individual preferences or prefer to disregard superfluous extras (WHAT?). Conversely, customers may wind up paying more for the final product than they would have for similar competing products because they chose additional optional features (WHAT?).

When creating a value proposition, businesses generally need to determine which selection of product features will yield the highest marginal utility for the greatest number of customers. Starting with the core functions of the basic product, each customer can then choose his or her preferred add-ons, so as to derive an optimal level of utility from the product.

The origins

The exact origins of this pattern are hard to trace. Additional offers or modular products have existed for a long time. Particularly in the case of services, it is logical to offer special services or additional features to fully exploit a customer’s willingness to pay more. Industrialisation also allowed companies to create modular products and consequently to offer additional features and extras.

All of us have, at one point, usually in the middle of the night, been tempted by that refreshing bottle of water in our hotel minibar. The hotel, however, charges quite a premium for this added service. Beverages and snacks cost a pretty penny. Taking a leaf from the hotel book, the tourism industry has since made wide use of the Add-On pattern. Tour operators such as cruise lines undercut each other to offer the best bargain, with packages that normally include basic transportation and accommodation on board for a low price. Staterooms with a balcony, shore excursions, beverages, special events, the gym and spa are then all available to customers at a premium.

The innovators

Ryanair, founded in 1985 as a regional Irish airline, is today one of the largest low-cost airlines in Europe. Ryanair follows a clear budget airline strategy. In 2011, the company had 76.4 million passengers, making it Europe’s largest airline, surpassing even Lufthansa – the next-largest airline with 65.6 million passengers at that time. An aggressive pricing strategy and a lean cost structure ensure the company’s profitability. These approaches are directly enabled by the Add-On business model that Ryanair pursues. Ryanair offers its basic fares at very cheap rates. Many complementary extras such as on-board service, meals and beverages, travel insurance, priority boarding, additional or excess baggage are then charged separately. Moreover, many other costs are passed on to customers, which are included as an add-on in customers’ invoices. Several years ago, Ryanair’s Irish CEO, Michael O’Leary, told us in a strategy discussion, with an ironic smile: ‘There are three things important in business: costs, costs, costs. The rest you leave to the business schools’.

Add-On: how add-ons add up at Ryanair

The German automotive supplier Bosch, unable to serve the market in a comprehensive way, was forced to create a new business model for its engine production. Here’s why: a central part of each engine is the electronic control unit, which is a combination of hardware and software that has to be customised for each type of engine and car. Previously, Bosch had sold such customised hardware and software as a package to car manufacturers, who paid for it per unit produced (including a premium for hardware and software customisation). While suitable for large series of engines (to achieve economies of scale, as Bosch had to adapt the settings just once for the whole series), this procedure was not appropriate economically for smaller orders of engine series such as special sports cars manufactured in smaller quantities. To resolve this problem, Bosch founded a completely new legally separate entity, now called Bosch Engineering GmbH. When it was founded in 1999, it employed only ten people. The company builds upon standard hardware and offers customisation as a separate service, inbuilt software being customised as required to address specific customer needs. The new business model is also suitable for smaller orders, while large orders are still processed by Bosch itself. The strategic decision to establish a separate business model innovation unit turned out to be a success. By 2016, Bosch Engineering grew to over 2,000 employees and generated more than €170 million in revenues annually.

The Add-On business model is not only relevant for cost-competing industries but also for premium products. The car industry successfully applies the Add-On pattern: here, additional features and extras sometimes actually improve the contribution margin more than the production car itself. For example, when configuring a Mercedes-Benz S-Class, customers can choose from over a hundred premium options. Ranging from equipment packages to individual accessories, the price of a vehicle can easily be increased by more than 50 per cent over the price of the standard model. In line with this, electric car manufacturer Tesla offers various performance add-ons even after the car has found its way to the customer’s garage. Unlike conventional cars, Tesla models, which CEO Elon Musk refers to as ‘computers on wheels’, can receive after-market upgrades without physical intervention. This is possible due to software updates, which enable an immediate activation of new features such as autopilot or enhanced acceleration.

Another example of the Add-On business model is SAP, a German software company that provides enterprise and management software for businesses. The company offers its standard business suite at a moderate price, but in order to exploit the full potential of SAP software, clients are encouraged to purchase additional features such as Customer Relationship Management, Product Lifecycle Management and Supplier Relationship Management applications. SAP’s additional software packages greatly extend the scope of services offered to clients. Customers can purchase basic software but are also able to specify a configuration precisely addressing their needs. In this way, SAP generates revenue from the basic product and from selling extras as required by the customer.

When and how to apply Add-On

The Add-On business model is especially well suited for hard-to-segment markets, where customer preferences often diverge vastly. Simply dividing products into different levels or versions is insufficient; and no optimal value proposition can be guaranteed for a large number of customers. Thus, it has become standard in the car industry to offer optional features and extras at a premium in addition to versioning the basic product. Recent consumer-behaviour research demonstrates that this is often the case for consumer products. Customers initially decide on the basis of rational criteria, including price, but later drift into emotionally driven purchasing patterns. Once you’re hunkered down in that tight economy seat, you don’t care how much that beer and sandwich are going to cost you.

The Add-On pattern can also work well in the B2B context, when multiple decision makers are involved: investors often try to minimise their upfront investment so as to maximise their profit when they sell their property later on; the cheapest air conditioning units, elevators and security systems will do. This leaves the facility management to deal with mounting service costs down the road. Similarly, the Add-On pattern can be used by your company to help certain technologies and accessories break through to the market. Often this requires add-ons to be cross-subsidised. In order to force acceptance of expensive technologies in the automotive industry, such as driving assistance systems, and to increase the number of units sold, these features are subsidised by add-ons.

Some questions to ask

- Can we provide a basic product to which customers can be price sensitive and then add on services?

- Can we lock our customers in so that they will buy the Add-On products from us?