6

LIFE-CYCLE POSITION, ADAPTABILITY, AND ORGANIZATIONAL STRUCTURE

Founders and entrepreneurs set the tone as they form their new organizations, so leaders clearly create culture from the outset. But as these organizations mature, their cultures determine what kind of leaders they choose. They develop a very clear idea of what leadership is supposed to be in that environment, and they select people for senior jobs who match that profile. The same thing happens throughout the ranks. A young organization draws on a variety of talents to achieve success, but as it ages, it develops strong beliefs, expressed in job descriptions, about what kinds of talent are needed and then recruits only those people. Talent management in the very mature organization then becomes a subtle process of the culture just re-creating itself, of hiring only people who “fit” in both the technical culture (how tasks get done) and the social culture (how relationships work in the organization). When the outside environment, or microculture, changes, organizations arrive at a moment of truth: We need innovation, yet we can't get our people to do it!

—Edgar Schein1

If we can agree that the economic problem of society is mainly one of rapid adaptation to changes in the particular circumstances of time and place, it would seem to follow that the ultimate decisions must be left to the people who are familiar with these circumstances, who know directly of the relevant changes and of the resources immediately available to meet them. We cannot expect that this problem will be solved by first communicating all this knowledge to a central board which, after integrating all knowledge, issues its order. We must solve it by some form of decentralization.

—Friedrich Hayek2

LIFE-CYCLE GUIDEPOSTS

The firm's competitive life-cycle was introduced in Chapter 4 and illustrates significant stages throughout a firm's life. Even though competition inevitably forces economic returns toward the cost of capital, for a period of time a firm can overcome the typical fade pattern due to competition and produce increasing economic returns (e.g., as previously noted, Apple's subsequent surge in profitability after Steve Jobs returned to the company).

At any point in time, a firm or one of its business units can be positioned on the competitive life cycle. The critical management task for each specific life-cycle stage is shown in the bottom of Figure 6.1.

In the high innovation stage, top priority should be given to test the validity of those assumptions that are critical to future business success. Management should be especially careful about automatically assuming that what worked in the past will work in a much different future. In 2004, Michelin management agreed with the forecast made by the consumer research firm J. D. Powers and Associates that within six years, 80% of new cars would be sold equipped with Michelin's run-flat tires. Many years before, Michelin invented the radial tire which quickly gained wide adoption. Management assumed that their new invention of run-flat tires would follow a similar path to commercial success. But the introduction of run-flat tires resulted in a major financial loss to Michelin primarily due to ignoring the role of service centers. The owners of the service centers were not motivated to purchase the expensive equipment to repair run-flat tires and incur training expenses to gain Michelin certification—significant upfront costs with only the prospect of meaningful revenue in the distant future if run-flat tires were widely adopted.3

FIGURE 6.1 Competitive life-cycle stages and key management tasks

FOCUSED EXECUTION OF AN INNOVATIVE BUSINESS MODEL—NETFLIX

A different business outcome followed a key assumption about consumers that led to Netflix pioneering the delivery of personalized entertainment over the Internet after starting in 1997 as a DVD-rental-by-mail operation. The original DVD rental business offered higher quality compared to low resolution videotapes. Netflix cofounder and CEO, Reed Hastings, recalls when he formulated the key assumption:

I had a big late fee for Apollo 13. It was six weeks late, and I owed the video store $40. I had misplaced the cassette. It was all my fault. I didn't want to tell my wife about it. And I said to myself, “I'm going to compromise the integrity of my marriage over a late fee.”… I started thinking, “How come movie rentals don't work like a health club, where, whether you use it a lot or a little, you get the same charge?”4

Not only was this core assumption confirmed, but Netflix has continued to successfully experiment (test assumptions) with different ways to create value for customers. Netflix's DVD business attracted competition from Amazon and Walmart. With a focus on the long term, Hastings and his partner Marc Randolph early on recognized both the potential for video-on-demand to obsolete the firm's DVD business and the importance of Netflix being flexible as to technology. They positioned Netflix to decentralize entertainment via the Internet.

Blockbuster used physical stores for distribution, which eventually became an anchor making it difficult to change course to a video-on-demand business model and compete with Netflix. Blockbuster management had an opportunity in 2000 to acquire Netflix for $50 million and declined, which will probably rank as the biggest missed deal of the century. What Blockbuster management did not see was the potential for fast-learning, highly motivated entrepreneurs to create value at a huge scale through early and smart strategic moves with a sharper eye on the future than their competitors.

On their website, Netflix management sums up their current business model:

Netflix is a global Internet entertainment services network offering movies and TV series commercial-free, with unlimited viewing on any Internet-connected screen for an affordable, no-commitment monthly fee. Netflix is a focused passion brand, not a do-everything brand: Starbucks, not 7-Eleven; Southwest, not United; HBO, not Dish.

We are about the freedom of on-demand and the fun of binge viewing. We are about the flexibility of any screen at any time. We are about a personal experience that finds for each person the most pleasing titles from around the world.5

Figure 6.2 displays Netflix's life-cycle performance.

The life-cycle chart in Figure 6.2 shows CFROIs sharply declining after 2010 while asset growth rates were maintained at extraordinarily high rates (approximately 35% per year). Management purposively sacrificed short-term profitability in order to make huge investments, particularly in original programming, to secure the leadership position in online entertainment. The success of this strategy was reflected in Netflix's rapid growth in subscribers. From 2002 to 2018, Netflix's shareholders outperformed the S&P 500 approximately 100-fold (see bottom panel). In 2016, the magnitude of Netflix's growth was emphasized by Vladimir Medinsky, Russian Minister of Culture, when he asserted that Netflix was on the government payroll and the White House had figured out “how to enter every home, creep into every television, and through that television, into the head of every person on earth, with the help of Netflix.”6

As Netflix transitioned from a successful startup to an established firm in the competitive fade stage, top priority was given to expansion with new capabilities as needed. Netflix launched a new streaming video product in 2007 when existing technology was slow with poor resolution. However, the firm invested heavily to improve their streaming technology well in advance of competitors. Note that Netflix's software to evaluate subscribers' preferences can also inform management as to the type of original content movies and TV series that will likely be well received. Netflix's high reinvestment rates facilitated expansion into original content of high quality and increased its global subscriber base. The firm has excelled in knowledge building, especially in building local knowledge in countries outside the United States. Local knowledge includes insights about political, institutional, cultural, and technical issues facilitating a remarkable expansion to 190 countries in seven years.7 This suggests sustained high CFROIs in the future, which has been duly noted by investors as shown in the bottom panel of Figure 6.2. However, competition is relentless, and the preeminent original content provider, Disney, has entered the streaming service business; this may well dampen Netflix's future growth.

FIGURE 6.2 Netflix 2000 to 2018

Source: Based on data from Credit Suisse HOLT global database.

Netflix is a huge winner in the New Economy. We would expect such a firm to be grounded in a robust, knowledge-building, value-creating culture. On the firm's website is an extensive description of the Netflix culture which is condensed into five points.

- Encourage independent decision-making by employees.

- Share information openly, broadly, and deliberately.

- Be extraordinarily candid with each other.

- Keep only our highly effective people.

- Avoid rules.

Feedback is an especially important component of the knowledge-building loop of Figure 2.1 and is critical to the Netflix culture in terms of sharing information and being extraordinarily candid.

We believe we will learn faster and be better if we can make giving and receiving feedback less stressful and a more normal part of work life. Feedback is a continuous part of how we communicate and work with one another versus an occasional formal exercise. We build trust by being selfless in giving feedback to our colleagues even if it is uncomfortable to do so. Feedback helps us avoid sustained misunderstandings and the need for rules.8

In the competitive fade stage, a firm is generating high economic returns with significant reinvestment rates. Maintaining such stellar life-cycle performance (favorable future fade rate) requires management to seize opportunities to create significant value that may exceed the firm's current capabilities. The so-called management truisms of “stick to the knitting” and “focus on the core” are a recipe for fast fade.

Amazon has avoided the type of culture (described by Edgar Schein at the beginning of this chapter) which perpetuates particular skills/talents resulting in a firm becoming incapable of significant innovation in a world that experiences significant change. Here Jeff Bezos describes Amazon's innovation process.

Companies get skills-focused, instead of customer-needs focused. When [companies] think about extending their business into some new area, the first question is “Why should we do that—we don't have any skills in that area.” That approach puts a finite lifetime on a company, because the world changes, and what used to be cutting-edge skills have turned into something your customers may not need anymore. A much more stable strategy is to start with “What do my customers need?” Then do an inventory of the gaps in your skills. Kindle is a great example. If we set our strategy by what our skills happen to be rather than by what our customers need, we never would have done it. We had to go out and hire people who know how to build hardware devices and create a whole new competency for the company.9

INNOVATION IN THE OPERATING ROOM—INTUITIVE SURGICAL

Figure 6.3 illustrates the life-cycle performance of Intuitive Surgical. In the early years, the firm was in the high innovation startup stage proving its technology. In 2001, the FDA approved the da Vinci robotic surgical system for prostate surgeries with the goal of less invasive surgery, reduced surgical errors, and faster patient recovery times. By 2018 nearly 5,000 da Vincis were employed in operating rooms for one million surgeries per year. As shown in Figure 6.3, high economic returns and high asset growth rates have been sustained during the competitive fade stage of Intuitive Surgical's life cycle. As to expanding its capabilities, the firm has developed expertise in systems, instruments, stapling, energy, and vision while moving beyond its mainstay prostate operation to include hernia and lung procedures. Recent technological R&D has addressed augmented reality, big data analytics, and artificial intelligence.

FIGURE 6.3 Intuitive Surgical 2000 to 2018

Source: Based on data from Credit Suisse HOLT global database.

Figure 6.3 shows the firm in the startup part of the high innovation stage occurring from 2000 to 2005. During this period, large investments were made in order to develop its robotic technology. Investors began realizing the firm's potential from 2003 to 2005 when the stock sharply outperformed the S&P 500, illustrated with the rising relative wealth index in the bottom panel of Figure 6.3. The top and middle panels of this figure document that the firm did deliver exceptional life-cycle performance 2006 to 2018, which resulted in significant shareholder rewards.

Intuitive Surgical aptly exemplifies an important point made in Chapter 1 (see Figure 1.1): the benefits to society from a successful business innovation far exceed the benefits to the firm's shareholders. Although difficult to precisely quantify, a strong case can be made that the past and future benefits to patients from robotic surgery far exceed the rewards to Intuitive Surgical's shareholders.

By way of background as to the impact of CEOs who manage high-technology firms, an important study focused on “Inventor CEOs” who have a personal track record of being awarded patents.

We show that firms led by Inventor CEOs are associated with a greater volume of registered patents, more highly cited patents, higher innovation efficiency, and a greater propensity to produce ground-breaking, or disruptive innovations.… CEOs with high impact inventor experience, as well as CEOs who maintain first-hand involvement in their firm's innovation, have an incrementally positive effect on their firm's patent output and impact.… Firms exogenously switching from Inventor to non-Inventor CEOs experience a significant decline in corporate innovation … our results paint a consistent picture of the unique innovation-enhancing capabilities that CEOs with hands-on experience “doing” innovation bring to their firms.10

Here is a concrete example of one CEO's innovation-enhancing capabilities. Gary Guthart, CEO of Intuitive Surgical since 2010, has a PhD in Engineering Science from the California Institute of Technology, and there is a long list of patents owned by Intuitive Surgical with Guthart listed as one of the inventors. Since he became CEO, his managerial skill coupled to his technical expertise has contributed to the firm's enviable track record. That track record has recently attracted competitors, including Medtronic and a startup, Verb Surgical, funded by Johnson & Johnson and Alphabet (Google).

Intuitive Surgical creates value primarily through the intangible (human) capital of its employees, which differs from the Old Economy with winners achieving scale advantages through tangible capital (factories). The next section reviews how management of an Old Economy firm did not wait for Silicon Valley startups to disrupt its business.

NOTHING RUNS LIKE A DEERE

John Deere represents an especially strong brand for farmers. The company began in the mid-1800s when John Deere, a blacksmith, constructed a rugged, high-performing plow from a steel sawblade. Noted for its tractors and other farm equipment, the company also manufactures construction, forestry, industrial, and lawn care equipment. All of these products face stiff competition.

As noted earlier, strong brands have an emotional connection to customers. Deere has earned that loyalty through long-term innovation and reliability. During the Great Depression in the early 1930s, for example, Deere lent money to struggling farmers.

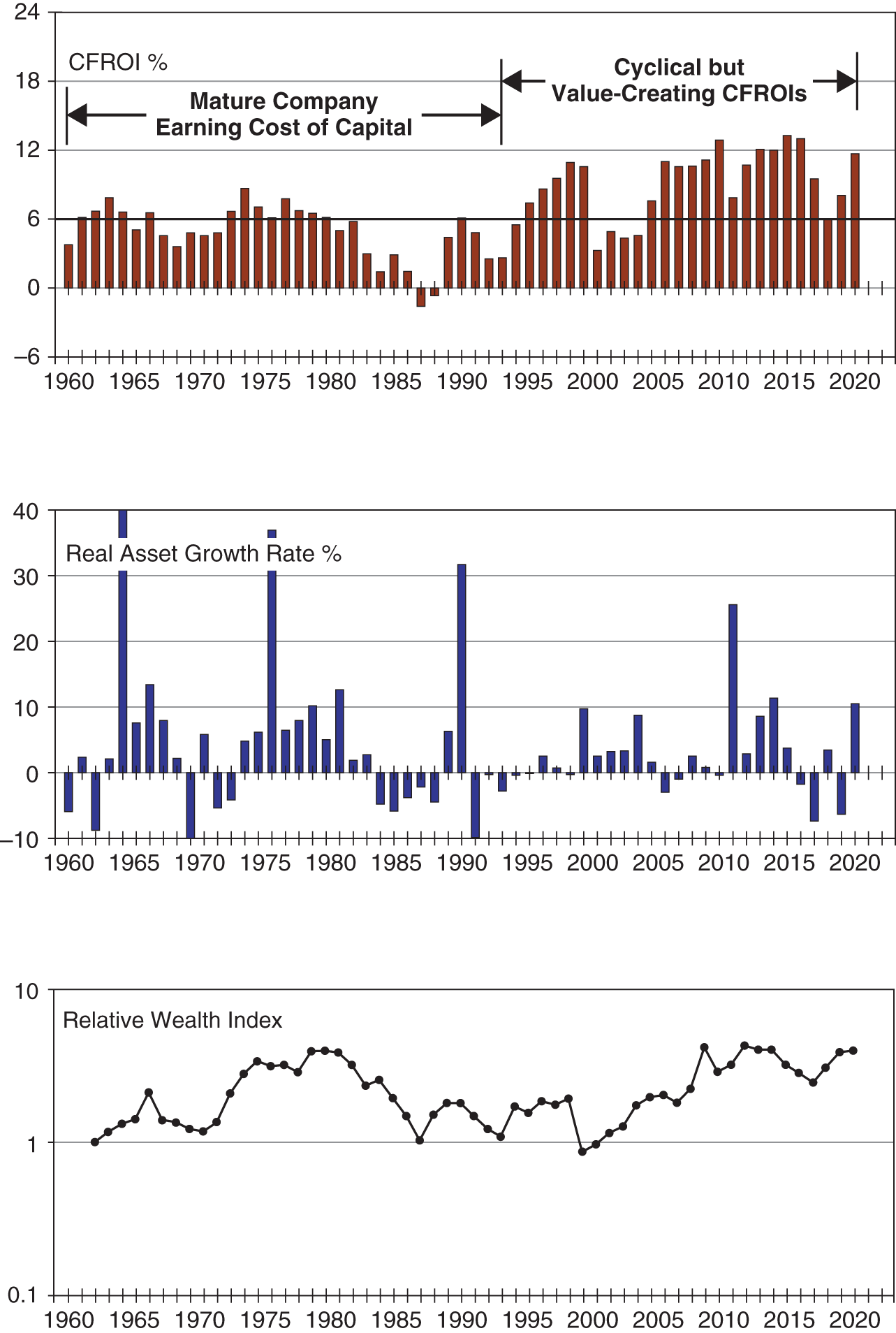

From 1960 to the early 1990s Deere was in the mature life-cycle stage earning approximately the cost of capital economic returns (dark horizontal line at 6% real in the top panel of Figure 6.4). The next 25 years displays cyclical and mostly value-creating CFROIs in excess of the cost of capital. What caused this improvement?

FIGURE 6.4 Deere 1960 to 2018

Source: Based on data from Credit Suisse HOLT global database.

Management adapted early to fundamental change: In order to better compete in a changing global environment of heightened competition, management implemented a financial discipline known as SVA (Shareholder Value Added). SVA's objective is to coordinate decision-making, especially resource allocation decisions, to deliver economic returns greater than the cost of capital. Consistent with this renewed focus on value creation and efficient innovation, Deere evolved from a product-centric business to incorporate a platform-centric capability to better compete in the digital world of the New Economy.

Deere intends to be the global leader in precision agriculture that enables farming with Deere products to be automated and more precise across the production process. The Deere platform exploits the Internet of Things (IoT) environment with sensors on their machines and probes in the soil. Software tools, data sharing, and artificial intelligence (AI) help their customers increase yield and decrease costs in all phases of farming.

In 2017, Deere acquired Blue River Technologies, which uses computer vision and machine learning in order to radically reduce the use of herbicides by spraying only where weeds are growing. Management has staked out a high-tech future.

When you say IoT, you normally think of things that fit in your pocket. The “T” for us is ten-ton tractors. Our large equipment now has … modems, with WiFi and Bluetooth, and that does two-way communication so it collects data off your farm and sends it to the cloud. It also takes instructions from Deere or from dealers or other software companies and sends it to the machine … tells the machine what to do.

Our roadmap is calling for machine learning and AI to find their way into every piece of John Deere equipment over time. What we do with our eyes can be done more accurately with a camera and a computer, with a system that retains that data and never forgets, and gets smarter with every pass of the field. This also applies to our construction and heavy equipment divisions.11

SMITH CORONA AND NCR

The key managerial task for firms in the failing business model stage is to purge a business-as-usual culture and reject an obsolete business model ill-suited to today's changing world. But this can be difficult for top management whose past successes and promotions were likely achieved because they skillfully executed the existing business model. Moreover, reliance on what has worked in the past (assumptions) is not at all easy to purge from one's knowledge base absent concrete feedback about change taking place that is likely to impair the existing business model. Successful adaptation entails major resource allocation decisions, the redirection of existing capabilities and the building of new capabilities, and at times, the acceptance of a much smaller and refocused company that can efficiently deliver value to customers at its smaller size. Let's briefly review the histories of two firms that were in the failing business model stage of their life cycle, Smith Corona and NCR. The former eventually went bankrupt while the latter was revitalized.

In the late 1800s, the Smith Premium Typewriter Company redirected its expertise in mechanical processes and manufacturing techniques for firearms to making and selling typewriters. In 1926, the firm merged with Corona Typewriter Company. The combined entity, Smith Corona, quickly gained the leading share of the typewriter market in the United States. After World War II, the firm produced a major innovation, the world's first portable electric typewriter and, by 1980, had a 50% share of the typewriter market. After being acquired by Hanson Trust in 1986 and doing an IPO in 1989, Smith Corona filed for bankruptcy just six years after its IPO.

Feedback ideally facilitates new knowledge building that is critical in directing innovation both for existing products and new products that may significantly differ from existing products. Smith Corona developed a capability in electronics but only applied this skill to enhance typewriters and word processors. With falling profits, management did initiate workforce reductions and asset sales but these funds merely continued business as usual.

The core problem was a serious lack of knowledge-building proficiency that resulted in top management and the board of directors committing to new products based on a faulty assumption about the power of the Smith Corona brand. They assumed that the well-known Smith Corona brand could be advantageously used in products for home and office use that were not typewriters. Their failure to early on rigorously test this assumption led to a multitude of undifferentiated and unsuccessful products, manufactured for the most part by other firms, and carrying the Smith Corona name. Consumers were not impressed because they viewed the quality implied by the Smith Corona brand as belonging specifically to typewriters.12

In addition, management was exceedingly slow to recognize how personal computers would sharply decline in price while simultaneously making huge improvements in user functionality. More adverse change was afoot since the small stores that had deep relationships with Smith Corona were being put out of business by new super-stores such as Walmart. All the while, the firm's culture was rooted in the slow changes to typewriters that occurred over 100 years, not the seismic changes in the blink of an eye that accompanied the personal computer revolution.

With hindsight one can analyze a company's long-term history and pinpoint “causes” of a decline in profitability and even bankruptcy. Oftentimes, such an analysis suggests that the root causes were either strategic errors or slowness in developing new capabilities. However (as readers might anticipate), I believe the root cause of either exceptionally good or bad long-term performance lies in the firm's knowledge-building proficiency. The captain of the firm's knowledge-building ship is the CEO. When CEOs adapt to a changing environment at a snail's pace, maintain organizational structures ill-suited to a new world, and make strategic mistakes, this is emblematic of a flawed knowledge-building process. The fix, if it is not too late, is a new CEO highly skilled in building knowledge and bringing business experience and leadership skill that enables him or her to hit the ground running.

This may be one of those “obvious once you think about it” observations. Yet, top management positions are often assigned to those with stellar track records in decision-making within a system attuned to what worked well in the past with minimal attention to an executive's skill in orchestrating knowledge, especially feedback about the external environment. That knowledge-building skill enables a manager to excel in different contexts, much like Lou Gerstner's managerial skill (quoted in Chapter 2) that enabled him to successfully restructure IBM.

When a firm has been managed for a long time by one or more CEOs accustomed to success in a slow-changing competitive environment, expect a firm-wide culture with processes (our way of doing things) with deep roots. This is because these processes have had a long undisturbed time to grow deep roots, even though more efficient ways of doing things may be achievable.

Let us now review how NCR faced no less a difficult situation due to a failing business model.

The NCR story begins as the National Cash Register company founded by John H. Patterson in 1884. In 1911, NCR sold 95% of the world's cash registers, and later its product line expanded to include adding and accounting machines. These were complex electromechanical products designed and manufactured in one integrated facility in Dayton, Ohio. In 1938, an in-house research effort began to explore electronics. In the early 1950s, NCR added a fourth product line—digital computers—and acquired Computer Research Corporation (CRC). NCR management viewed computers as distinct from its other products and believed that computers represented an evolution not a revolution.13

Management extrapolated the past slow evolution of cash register innovations, which NCR basically controlled, to apply to computers in the future. They concluded the firm's existing organizational structure focused around electromechanical technologies was satisfactory. Product development attuned to slow-moving change remained intact, quite contrary to CRC's forward-looking founders focused on fast-paced change. Eventually, CRC's manufacturing personnel were laid off. An ill-conceived joint venture was formed with General Electric given responsibility for manufacturing computers. NCR's R&D staff remained in Dayton surrounded by a legacy of mechanical engineering. Business-as-usual reinvestment was maintained in yesterday's technologies. At the massive manufacturing facility in Dayton, thousands of mechanical parts were made, even including screws—nothing was outsourced. Manufacturing costs were excessive, and inefficient work processes proliferated, insulated by union work rules.

Retail firms, the mainstay of NCR's long-term business relationships, wanted computerized point-of-sale systems; but NCR salespeople responded by demonstrating the newest features to existing products that they asserted would maintain a wide cost advantage over any future computerized products. IBM soon gained dominance in the computer industry with the introduction of its 360 series. Meanwhile, William Anderson was running NCR's business in Japan and delivering impressive results. He was unusually skilled in learning about what customers really needed, and he even developed an electronic cash register suited to local needs.

Think for a moment about the degree of difficulty in restructuring NCR as profits plummeted in the early 1970s and 100,000 employees were entrenched in a culture of fossilized processes that guaranteed failure in the new electronics world. That task went to William Anderson, who became CEO in 1972.

In contrast to Smith Corona's failure to make a radical break from the past, Anderson literally declared martial law for NCR. Upon assuming his leadership role, he quickly taped a video to employees plainly communicating that business as usual no longer works: “Complacency and apathy—these are NCR's greatest sins. Until we see a return to profitability, something akin to martial law will be in effect in Dayton.”14

Keep in mind that Anderson survived being a POW in a Japanese prisoner camp during World War II. His biography reflects an individual with unique determination and skill in learning about change, in leading people, and in organizing resources to deliver products and services that genuinely created value for customers.15 He made his mark in Japan outside of the stifling bureaucratic culture of Dayton.

Fortunate for Anderson, NCR's board of directors fully supported the needed organizational restructuring initiated by Anderson. New product development was moved from Dayton to self-contained business units that primarily out-sourced the supply of electronic components. The sales force was organized to focus on particular types of customers complemented by field engineers to service customers. Large-scale layoffs were unavoidable. Anderson's deep knowledge of customers led him to reverse NCR's strategy of treating computers as a distinct product independent of NCR's other products. He believed that NCR had to connect its terminals to host computers manufactured by NCR thereby delivering to customers a complete system. As Anderson successfully orchestrated the transition to electronic systems, NCR's 3% CFROIs at the beginning of his tenure rose to 10% prior to NCR merging with AT&T in 1991. Sadly, the AT&T bureaucratic culture resulted in the wholesale loss of NCR's senior management, and the merger proved to be a financial disaster. NCR again became a public company in 1997.

Smith Corona's bankruptcy and NCR's successful restructuring illustrate how top management's worldview based on assumptions rooted in past experiences shape perceptions and actions taken or not taken. Particularly important is a CEO's cognitive process for perceiving the world and learning about change.

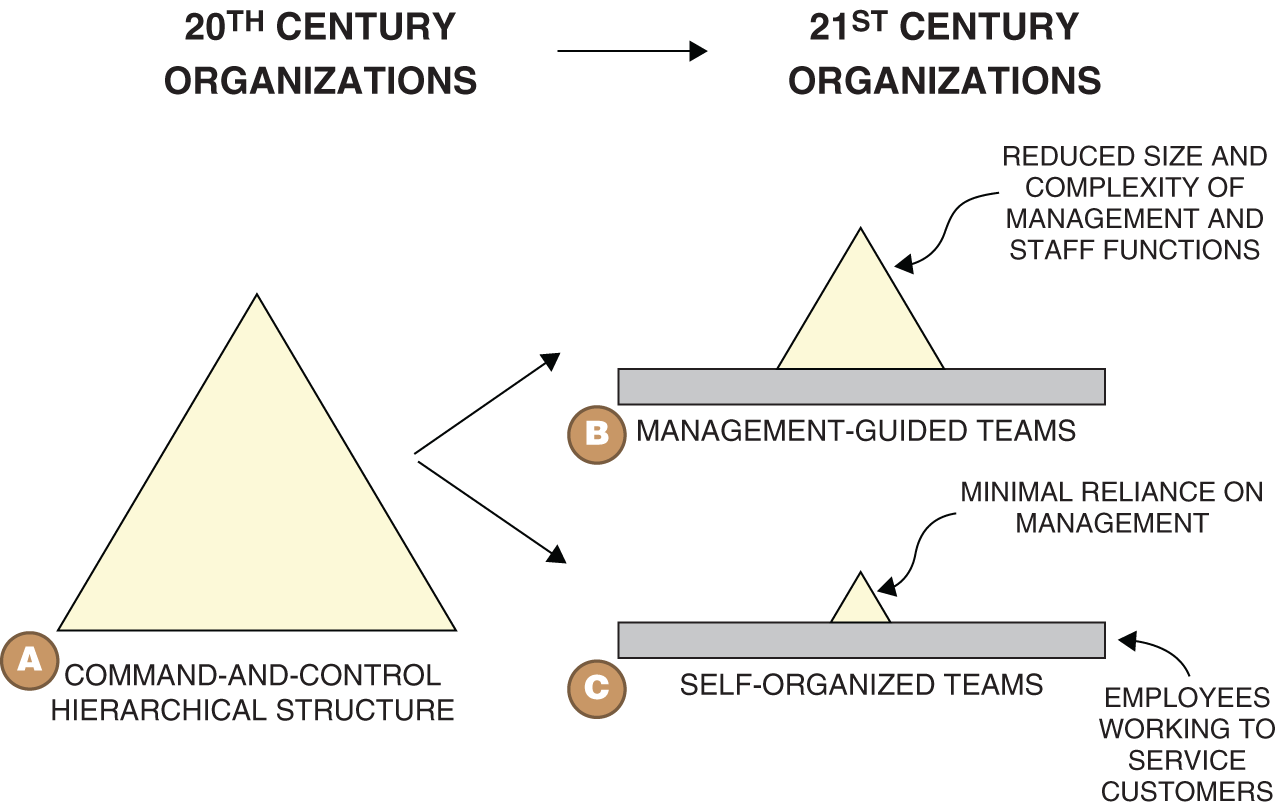

The ABCs of Organizational Structure

As firms grow large, they tend to add layers of management and silos of expertise in order to increase control of operations. This results in a proliferation of rules and regimented ways to achieve targets set by the next higher-up management level. The end result is a bureaucratic, command-and-control hierarchical structure with decisions made at the top that translate into marching orders for those at the bottom of the hierarchical pyramid. Information is limited to those who need it according to their position in the hierarchy. This structure is labeled type-A in Figure 6.5.

Many have argued that 21st-century organizations can create far more value for customers and other stakeholders by transitioning to an organizational structure that flattens the hierarchical pyramid.16 Such a structure focuses on teams comprised of individuals doing the work of efficiently serving customers. In Figure 6.5, organization type-B reflects sharply reduced layers of management (shrunken pyramid).

During his tenure as CEO of Nucor from 1965 to 1996, Ken Iverson nurtured a flattened, type-B organizational structure focused on supporting teams in the steel mills so that managers enabled an environment that frees employees to determine what they do and should do, to the benefit of themselves and the business. Recall the discussion in Chapter 3 about Toyota's preeminent lean manufacturing system focused not on managers telling employees what to do, but employees guided by mentors who are skilled in asking questions that help employees solve problems, all the while employees are improving their knowledge-building skills.

FIGURE 6.5 Three types of organizational structure for business firms

When a firm's CEO (perhaps a founder) has been at the helm for a long period, the firm's organizational structure can evolve into a shape preferred by the CEO. Key ingredients to Netflix's culture, noted earlier, include sharing information broadly, being extraordinarily candid with each other, and avoiding rules. These desirable type-B characteristics are far easier to achieve for a firm like Netflix, which has had the same CEO for its entire existence. Changing from a type-A (especially so for a large firm) to a type-B is an exceptionally difficult challenge. Why? At all levels of the firm, people have evolved a worldview of how to do things rooted in assumptions based on experiences within a command-and-control hierarchy. Not so easy to change, which is why type-B firms face difficulty with integrating managers who have spent a long time working in type-A environments.

What can we learn from type-C firms that have nearly eliminated management and transferred most or all of the control and responsibility for running the firm to those employees doing the work? Let us review some type-C firms beginning with Morning Star Company, the world's largest tomato processor.17 The company operates in an extraordinarily decentralized manner.

Chris Rufer has been the leader of Morning Star since he started the company in 1970. The company began as a trucking operation and still distributes processed tomato products with its trucks, in addition to harvesting the tomatoes. Their website describes a unique vision of self-management focused on efficiently serving customers and generating superior economic performance. Annual industrial sales are approximately $350 million and, although financial statements are not public, the firm's performance is generally acknowledged to be superior.

The Morning Star Company was built on a foundational philosophy of Self-Management. We envision an organization of self-management professionals who initiate communication and coordination of their activities with fellow colleagues, customers, suppliers and fellow industry participants, absent directives from others. For colleagues to find joy and excitement utilizing their unique talents and to weave those talents into activities which complement and strengthen fellow colleagues' activities. And for colleagues to take personal responsibility and hold themselves accountable for achieving our Mission.

To be an Olympic Gold Medal performer in the tomato products industry. To develop and implement superior systems of organizing individuals' talents and efforts to achieve demonstrably superior productivity and personal happiness. To develop and implement superior technology and production systems that significantly and demonstrably increase the effective use of resources that match customers' requirements. To provide opportunity for more harmonious and prosperous lives, bringing happiness to ourselves and to the people we serve.18

It is refreshing to read about Morning Star's blending of demonstrably superior productivity (Olympic Gold Medal performer) and personal happiness. This is the path to a sustainable firm that resonates with the four-part purpose of the firm (Chapter 1), which includes win-win relationships with employees and the need to at least earn the cost of capital over the long term; otherwise, the firm's stakeholders are guaranteed to suffer.

Many studies about Morning Star conclude that its colleagues (employees) are exceptionally motivated, productive, and enjoy their work environment.19 Notable is an absence of managers so that colleagues interact in order to negotiate and agree on goals and responsibilities. No job titles and no promotions. Compensation is peer-based. An especially important component in the firm's self-management system is its Colleague Letter of Understanding (CLOU). The author of a CLOU negotiates with other colleagues most impacted by that person's work on personal goals and performance metrics. Colleagues work as part of business units with their own profit and loss statements, which can require negotiated customer-supplier agreements. Colleagues make decisions on ordering equipment or whatever they feel is needed to fulfill their CLOUs. Large expenditures require agreement with a wide number of colleagues.

This system of self-management works for Morning Star. Most remarkable is how bureaucracy has been essentially eliminated and colleagues work in a way that is productive, builds teamwork, is beneficial to customers, and is fulfilling (sense of genuine accomplishment). Since promotions and related job titles are eliminated, colleagues advance by way of adding responsibilities and peer recognition. Information is widely shared—no information silos like those in conventional type-A pyramid organizations. Performance of units and individuals is regularly reviewed by colleagues. Conflict resolution is achieved through mediating colleagues and is critical in maintaining a balance between freedom and responsibility. Striving to build up one's reputational capital (and also one's peer-determined compensation) is a hand-in-glove fit with teamwork, which is a hallmark of Morning Star's self-management system.

One criticism of Morning Star is that the firm's type-C structure may not handle radical innovation well. This situation has not impacted Morning Star due to the stability of the tomato processing industry with its reduced concern for product obsolescence and reliance on incremental improvements for processing tomatoes. The previously mentioned Ken Iverson, while CEO of Nucor, not only orchestrated a lean type-B organization but was the key person responsible for a bet-the-firm technology decision to invest in an untested (at scale) innovation—mini-mills that use electric arc furnaces to melt scrap steel. Would a type-C steel company, in circumstances similar to Nucor, make such a bet-the-firm decision? In a similar vein, would Intel have been better served by a type-C organization instead of having Andy Grove calling the shots to abandon manufacturing dynamic memory (its primary source of revenue) and switch to manufacturing microprocessors?

In contrast to Morning Star, Valve is a type-C firm in a fast-paced, volatile industry. In 1996, Gabe Newell and Mike Harrington started Valve as a traditional game company with a core competency in writing software code. Today, the firm has characteristics of an entertainment/software/platform company. Valve is populated by innovative employees who work in a decidedly flat organization with almost nonexistent management control. Employees are self-directed in that they select projects to work on that potentially will make good use of their skills and create genuine value for customers. The firm stresses knowledge building and especially experiments involving predictions and comparisons to forecasted results, thereby evaluating assumptions. Over the years, Valve created many popular games. In 2008, the firm released Steam, which is a platform of tools and services for game developers and publishers which quickly grew to 20 million users and over 500 games. Peer-driven performance reviews are used to better connect compensation to value created. Extreme importance is accorded to hiring the right people. As its Handbook for New Employees states:

Across the board, we value highly collaborative people. That means people who are skilled in all the things that are integral to high-bandwidth collaboration—people who can deconstruct problems on the fly, and talk to others as they do so, simultaneously being inventive, iterative, creative, talkative, and reactive. These things actually matter far more than deep domain-specific knowledge or highly developed skills in narrow areas. This is why we'll often pass on candidates who, narrowly defined, are the “best” in their chosen discipline.

We value “T-shaped” people. That is, people who are both generalists (highly skilled at a broad set of valuable things—the top of the T) and also experts (among the best in their field within a narrow discipline—the vertical leg of the T).

Valve's self-reported financial data show sales per employee and profit per employee greater than either Google or Facebook. Why? Valve hires exceptionally talented people able to effectively collaborate within an organizational structure designed to aggregate individual knowledge so that diversity-based, crowd-sourced, and highly effective decisions emerge. Simply put, employees evaluate projects by voting with their feet as to joining or not.20

One view of Valve's hyper-flat structure is that it is ideally suited to the creativity of highly skilled, innovative people and the collaborative culture that is so carefully nurtured. However, should not one be skeptical of such a type-C structure imposed on, say a global manufacturing firm with tens of thousands of employees making products like refrigerators and stoves, not computer games? It so happens that such a type-C firm exists. The corporate history of the Haier Group is a remarkable story.

ORGANIZATIONAL EXPERIMENTATION AT THE HAIER GROUP

In 1984, Zhang Ruimin became CEO of a small, near-bankrupt Chinese manufacturer of low-quality refrigerators. Ruimin is an example of a knowledge builder who relies on experimentation and feedback to orchestrate innovation not only for product design but also for the firm's organizational structure. Today, Haier Group is a multinational consumer electronics and home appliance firm that earns economic returns well in excess of the cost of capital and holds the leading global share of whitegoods (refrigerators, ovens, etc.). Figure 6.6 displays Haier's life-cycle track record from 2000 to 2018.

The Haier story can be viewed as a study of instilling dynamism in a country one company at a time. From a value-dissipating firm of 800 employees in 1984, the firm, at the beginning of 2019, had over 87,000 employees who efficiently deliver value to customers with a relentless focus on innovation.

FIGURE 6.6 Haier Group 2000 to 2018

Source: Based on data from Credit Suisse HOLT global database.

From 2000 to 2006, as seen in Figure 6.6, CFROIs declined below the long-term, inflation-adjusted (real), benchmark cost of capital of 6%, and Haier's stock underperformed the Shanghai Stock Exchange Composite Index as illustrated in the bottom panel. The improved financial performance since 2006 exceeded investor expectations, and the stock outperformed due to a sharp rise in CFROIs coupled to significant asset growth, including the 2016 acquisition of General Electric's appliance division for $5.4 billion.

Zhang Ruimin is an unusual CEO in that he views Haier's organizational structure as evolving in tandem with a continual knowledge-building process keyed to delivering high value to customers. In an interview he noted: “One of the biggest differences is our ability to remake and overhaul ourselves. Many companies' ways of thinking and operating have ossified and become hard to change, especially their organizational structures.”21

The Haier revitalization journey from the failing business model life-cycle stage began with Ruimin, shortly after becoming CEO, getting employees' attention as to the abysmal level of manufacturing quality. A total of 76 refrigerators with significant defects were destroyed with a sledge hammer by Ruimin and other employees even though each refrigerator was worth an employee's salary for two years. The dismal morale of employees and the decrepit condition of the Qingdao General Refrigerator Factory was evident in Ruimin's first rule: do not pee on the factory floor. Early on, he understood the key ideas of Lean Thinking and spoke of production flowing like a river with minimal inventories.22 So, the revitalization began with upgrading the firm's manufacturing processes. From 1984 to 1991, Ruimin managed a command-and-control hierarchical structure to dramatically improve quality, build a brand name that represented quality to consumers, and gain the dominant share of the Chinese market for refrigerators.

He saw opportunity in acquiring firms that were inefficiently managed but delivered quality products. From 1991 to 1998, Haier acquired many such firms. During this time period, Ruimin shifted from a command-and-control hierarchy to a decentralized organizational structure that transferred power to individual business units. From 1998 to 2005, Haier entered the most competitive international markets believing that his employees had the necessary skills to successfully compete. He also further evolved the organizational structure to operate with “zero distance” from customers., that is, eliminate any bureaucracy that impedes value creation. In terms of Figure 6.5, Haier was becoming a type-C organization with self-managed teams responsible for generating profits and allocating resources. This is a remarkable large-scale experiment in radically reducing layers of managerial control.

Zhang Ruimin further transitioned Haier in 2012 to a platform-based enterprise so that local employees can provide extensive customization and make customers lifetime users of Haier products and services. Ruimin's “rendanheyi” organizational structure replaces middle management with thousands of self-governing microenterprises. He explains:

In 2005, with the Internet economy in mind, we began making innovations in our business model that would help us adapt. We called our new model rendanheyi. Ren refers to the employees, dan means user value, and heyi indicates unity and an awareness of the whole system. The term rendanheyi suggests that employees can realize their own value during the process of creating value for users. This new model was intended to foster co-creation and win-win solutions for employees and customers.23

For the first few years, our performance didn't really pick up.… Some of our shareholders expressed concerns.… In our shareholders' meetings we explained that this is the model that we believe will lead to success, especially in this changing world where we were entering the Internet era.… Our performance started picking up in 2016. Our stock price doubled that year. In 2017, our stock price doubled again. This pick-up in performance was no coincidence. It was the accumulated effect of many years of working in the micro-enterprise model.24

Haier's strategy of mass customization and zero distance to customers is evident in its water purifiers which eliminate pollutants specific to each of 220,000 Chinese communities. Project teams closest to customers decide on resource allocations, and they have the freedom to obtain resources either inside or outside the firm. In addition, Haier's innovative, fast-paced culture has a reputation for nurturing, rewarding, and retaining high-performing employees. This management of talent may well be the key to the firm's success with its radical decentralization. Here is a perceptive assessment of Haier's culture that supports the foundational value of knowledge building: “Rather than pursuing scalable efficiency, Haier is experimenting with a corporate culture that can drive scalable learning.”25

Keep in mind that Ruimin's unique skill in decision-making and leadership was essential for Haier's transition to a type-C organization. Moreover, it is doubtful that the adoption in 2012 of the platform business model would have emerged solely from self-organized teams, absent his leadership. A strong case can be made that, for large, complex type-C firms, continued success requires a strong leader who promotes autonomy for teams/micro-enterprises while still orchestrating major strategic decisions as circumstances warrant.

Haier's organizational structure promotes efficiency at the micro (firm) level similar to the efficiencies realized by a free-market economy at the macro level. It is an understatement to say that this organizational evolution for a large multinational firm is uniquely important to building knowledge that could be applied to thousands of other firms.

Recall from Chapter 1 that the starting point of the firm's four-part purpose is a vision that is both inspiring and motivating. In that regard, Zhang Ruimin commented about his vision for Haier's Internet-based platform:

Today, we offer our resources to society, providing a Haier branded business platform to makers. This means that those innovators who are full of entrepreneurial passion, can develop new products within the Haier platform.

More than 100 small companies have been bred and hatched on Haier's cloud platform. They have left Haier to form stand-alone entrepreneurial enterprises. There are also social entrepreneurs making use of the Haier Internet platform to create businesses.… The makers on the Haier platform are both the entrepreneurs and the builders of our platform.… Haier strives to be a home and a community for great makers.26

To sum up: Haier is a compelling experiment in progress to learn about transitioning from a type-A organizational structure to a type-C. What else might we learn about innovation in China? That is addressed in the next section.

VALUE CREATORS DRIVE DYNAMISM IN CHINA

Entrepreneur is an entrenched word in our everyday language referring to one who innovates, usually by starting a new company. At a deeper level, entrepreneurs focus on a problem and develop or adapt a solution that potentially can create value for customers. The beginning point is knowledge building that results in value creation. Entrepreneurs over the age of 40 are five times more likely to succeed compared to entrepreneurs under 30. Those who studied engineering do better than those who studied business. Most entrepreneurs develop their ideas while working at large firms.27

Suppose the large firm green-lighted the innovative idea, and the person promoting the idea was given responsibility to build a team, develop the product, and execute a marketing plan. Would that person wearing a corporate hat be less of an entrepreneur? The key point is that value creator may be a more useful term for those, in general, who deliver significant benefits to customers by solving problems that may or may not require the startup of a new firm. The common thread is value creation. In my experience with students, they all want to be value creators while far fewer aspire to be an entrepreneur. Isn't value creator an accurate description of Zhang Ruimin at every stage of building Haier into a large multinational firm and a showcase of Chinese innovation?

China's economic resurgence has been fueled by manufacturing and investment enabling hundreds of millions of people to escape poverty. Dynamism is flourishing in China and reflected in jobs that bring discovery, opportunities to solve problems and to build new skills, and rewards that exceed monetary compensation. There is a tremendous growth of startup businesses and a steady rise in pioneering companies that have become global leaders, for example, Alibaba in e-commerce and retail, the Internet and AI technology company Baidu, the gaming and social media company Tencent, Lenovo, the dominant manufacturer of personal computers plus other electronic products, and Huawei, the world's largest patent filer, with global leadership in telecommunications and consumer electronics.

The rapid pace of innovation by Chinese companies is a radical departure from the days when China was viewed as a copycat economy. Today, there is a unique confluence of conditions that are highly supportive of business innovation.28

- Tremendous geographical diversity and range of consumer needs

- Regulatory environment that favors Chinese companies

- Expanding middle class with rising consumer demands

- Markets where good enough products give companies a toe-hold followed by rapid experimentation and improvement

- Heightened competitive environment equips survivors for continual fast-paced innovation and global expansion

- Return of highly educated and skilled Chinese who want to work for Chinese companies

- Culture that promotes networking and joint ventures, coupled to substantial R&D investment

- Availability of venture capital

- Centralized leadership structure for fast decision-making

The last bullet point regarding centralized leadership is particularly important and connects back to the earlier discussion of organizational structure. Mark Greeven, George Yip, and Wei Wei have extensively studied how Chinese companies innovate and they note:

Decision making in most Chinese companies is centralized with a strong leader.… Because many Chinese companies are young and lack bureaucratic management structures, they tend to be less formal and listen more to decisive bosses.

The organizational structures of Chinese innovators tend to be either flat or flexible.… Xiaomi [type-B firm that is a leader in smart hardware and electronics] … with eight thousand employees has only three organizational layers.… According to traditional management theory, it is not possible to manage in such a flat but large organization, but Xiaomi succeeded. The seven cofounders direct one layer of directors, who in turn manage the engineers and salesforce directly.29

The takeaway from this brief discussion of Chinese innovation is that other countries, loaded with type-A firms, had best consider shedding bureaucratic layers in order to compete with China's rising innovation powerhouse firms. A related takeaway is that changing a firm's organizational structure involves performance measurement and effective language, which was reviewed in Chapter 5.

NOTES

- 1 Edgar Schein in a conversation between Edgar H. Schein and Peter A. Schein, 2019, “A New Era for Culture, Change, and Leadership,” MIT Sloan Management Review Summer 60(4): 52–58.

- 2 F. A. Hayek, 1945, “The Use of Knowledge in Society,” American Economic Review 35(4): 519–530.

- 3 Ron Adner, 2012, The Wide Lens: What Successful Innovators See That Others Miss. New York: Penguin Group, pp. 17–23.

- 4 Matthew Honan, “Photo Essay: Unlikely Places Where Wired Pioneers Had Their Eureka! Moments,” Wired Magazine, March 24, 2008.

- 5 https://www.netflixinvestor.com/ir-overview/long-term-view/default.aspx accessed on 19 July 2019.

- 6 Tom Parfitt, June 24, 2016, “Netflix Is Just a CIA Plot, says Kremlin,” The Times.

- 7 Louis Brennan, 2018, “How Netflix Expanded to 190 Countries in 7 Years,” October 12, https://hbr.org/2018/how-netflix-expanded-to-190-countries-in-7-years.

- 8 https://jobs.netflix.com/culture accessed July 19, 2019.

- 9 Interview, April 16, 2008, “Bezos on Innovation,” Bloomberg Businessweek.

- 10 Emdad Islam and Jason Zein, forthcoming, “Inventor CEOs,” Journal of Financial Economics.

- 11 Interview with John Stone, SVP of John Deere's Intelligent Solutions Group, Scott Ferguson, March 12, 2018, “John Deere Bets the Farm on AI, IoT,” Light Reading.

- 12 Erwin Danneels, 2010, “Trying to Become a Different Type of Company: Dynamic Capability at Smith Corona,” Strategic Management Journal 32(1): 1–31.

- 13 Richard S. Rosenbloom, 2000, “Leadership, Capabilities, and Technological Change: The Transformation of NCR in the Electronic Era,” Strategic Management Journal 21: 1083–1103.

- 14 Linda Grant Martin, 1975, “What Happened at NCR after the Boss Declared Martial Law?” Fortune, September: 100–104.

- 15 William S. Anderson, 1991, Corporate Crisis: NCR and the Computer Revolution. Dayton, OH: Landfall Press.

- 16 Frederic Laloux, 2014, Reinventing Organizations: A Guide to Creating Organizations Inspired by the Next Stage of Human Consciousness. Brussels, Belgium: Nelson Parker. Also see a report published in 2017 by Gallup, State of the Global Workplace, which highlights findings from Gallup's ongoing study of workplaces in more than 140 countries.

- 17 Sharda S. Nandram, 2015, Organizational Innovation by Integrating Simplification: Learning from Buurtzorg Nederland. Basel, Switzerland: Springer. This book is a comprehensive analysis of Buurtzorg Nederland, a type-C firm that has significantly improved health care for patients served. In the Foreword to the book, the firm's founder Jos de Bok wrote the following:

In 2006 Buurtzorg Nederland was established. Some friends with a big ambition wanted to change the Dutch homecare into community care. Many patients were troubled by the fragmented way care was delivered and many nurses were frustrated because they couldn't perform the way they wanted to. We chose an organizational model which focuses on meaningful relationships and no hierarchy. We wanted to use IT in a way that it served the nurses. We wanted to work with people who could be proud of what they achieve: day in day out! We wanted to show that it's much more effective and sustainable to work this way and yes: we wanted to change the world (a little bit).

- 18 Website www.morningstarco.com, accessed July 26,2019.

- 19 Gary Hamel. 2011, “First, Let's Fire All the Managers,” Harvard Business Review, December, pp. 48–60.

- 20 Teppo Felin and Thomas C. Powell, 2016, “Designing Organizations for Dynamic Capabilities,” California Management Review 58(4): 78–96.

- 21 Art Kleiner, 2014, “The Thought Leader Interview: Zhang Ruimin,” Strategy + Business Winter 77: 96–102.

- 22 Jeannie J. Yi and Shawn X. Ye, 2003, The Haier Way: The Making of a Chinese Business Leader and a Global Brand. Dumont, NJ: Homa & Sekey Books.

- 23 Zhang Ruimin, 2018,. “Why Haier Is Reorganizing Itself Around the Internet of Things,” Strategy + Business, Summer 91.

- 24 Knowledge@Wharton, “For Haier's Zhang Ruimin, Success Means Creating the Future,” April 20, 2018, http://knowledge.wharton.upenn.edu/article/haiers-zhang-ruimin-success-means-creating-the-future/

- 25 Bill Fischer, Umberto Lago, and Fang Liu, 2013, Reinventing Giants: How Chinese Global Competitor Haier has Changed the Way Big Companies Transform. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, p. 220.

- 26 Hu Yong and Hao Yazhou, 2017, Haier Purpose: The Real Story of China's First Global Super-Company. Oxford: Thinkers 50.

- 27 Carl J. Schramm, 2018, Burn the Business Plan: What Great Entrepreneurs Really Do. New York: Simon & Schuster.

- 28 Xiaolan Fu, 2015, China's Path to Innovation. Oxford: Cambridge University Press. See also Yu Zhou, William Lazonick, and Yifei Sun, 2016, China as an Innovation Nation. Oxford: Oxford University Press; and George S. Yip and Bruce McKern, 2016, China's Next Strategic Advantage: From Imitation to Innovation. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- 29 Mark J. Greeven, George S. Yip, and Wei Wei, 2019, Pioneers, Hidden Champions, Changemakers, and Underdogs. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, pp. 125-126.