3

WORK, INNOVATION, AND RESOURCE ALLOCATION

The biggest barriers to strategic renewal are almost always top management's unexamined beliefs.

—Gary Hamel1

A manager argued that he could either increase his business unit's margins or its sales, but not both. His chief executive reminded him of the time when people lived in mud huts and faced the stark choice between light and heat: punch a hole in the side of your hut and you let the daylight in but also the cold, or block up all the openings and you stay warm but sit in darkness. The invention of glass made it possible to overcome the dilemma—to let in the light but not the cold. How then, he asked his manager, will you resolve your dilemma between no sales or no margin improvement? Where is the glass?

—Dominic Dodd and Ken Favaro2

FIGURE 3.1 Work, innovation, and resource allocation

Figure 3.1 highlights three components of a pragmatic theory of the firm—work, innovation, and resource allocation—that will be analyzed in this chapter. Much of this chapter focuses on work because innovation and resource allocation are recurrent topics in other chapters. These three components are connected to one another and deeply rooted in a firm's knowledge-building proficiency.

In Figure 3.1, the firm's purpose is the beginning point because the other components are either managerial tasks to achieve the firm's purpose or related performance results.

Keep in mind that a theory is useful if it provides new angles of thinking about important issues that yield practical insights. In addition, a useful theory brings a deeper understanding of the phenomena of interest, makes important predictions, and reveals problems and opportunities that otherwise are unnoticed. Some examples, which are covered in detail in later chapters, include how the firm's competitive life-cycle connects to the life-cycle valuation model (Chapter 4). This model uses a forward-looking discount rate derived from current market prices (similar to a bond's yield-to-maturity) instead of a backward-looking discount rate based on a widely varying forecast equity risk premium coupled to a stock's Beta. The Beta approach is often taught to finance students even though the numerical answers should not be trusted, so say leading scholars in finance and accounting (more on this in Chapter 4). And the discussion of intangibles in Chapter 5 includes a method for investors to handle the qualitative nature of how intangibles impact competitive advantage by way of a long-term forecast of the “fade” rate of economic returns. In addition, Chapter 5 makes the case that the large-scale research program in mainstream finance focused on correlating factors with excess investor returns is of limited use to managements (for sure) and, with the exception of some quantitative factor investing styles, of limited use to investors. It's far better to focus on the root cause of excess returns for stocks, which is the difference between expected versus actual firm performance, which is easily expressed in life-cycle terms as economic returns and reinvestment rates.

In the following three sections, I will explain why Lean Thinking and the Theory of Constraints generate significant gains in the productivity of work in firms. Also, a new approach, the ontological/phenomenological model, orchestrates performance improvement based on how the world occurs to people. Extensive quotes from those especially knowledgeable about these three performance-enhancing initiatives are showcased.

LEAN THINKING—“NO PROBLEM IS A PROBLEM”

After World War II, Toyota had little financial resources when Tachi Ohno began the development of the Toyota Production System for manufacturing automobiles. Lean Thinking, as illustrated in Figure 3.2, is not a theory but a systematic way of thinking in order to rely less on investments in high-capacity machines and more on human capital to continually improve how work is done, and to minimize waste. Ohno's manufacturing insights originated with his study of how Henry Ford organized work in the 1920s so that iron ore mined on a Monday could be used to produce a car that rolled out of his assembly line on Thursday.

FIGURE 3.2 Lean Thinking

Ohno focused on pulling work through a factory, avoiding the conventional push system of mass production which uses high-capacity machines resulting in large work-in-process inventories that hide many sources of waste. He put it simply:

All we are doing is looking at the time line from the moment the customer gives us an order to the point when we collect the cash. And we are reducing that time line by removing the non-value-added wastes.3

James Womack and Daniel Jones, two of the leading proponents of Lean Thinking, describe five fundamental lean principles as: “precisely specify value by specific product; identify the value stream for each product; make value flow without interruptions; let the customer pull value from the producer; and pursue perfection.”4 When management nurtures and sustains a lean culture, expect high quality and less resources consumed, that is, less capital investment, less physical space, and less employee time to deliver value to customers. In a nutshell, Lean Thinking optimizes the flow of products or services through value streams which encompass the entire production process of a product, including suppliers and distributors. Skilled lean practitioners have a worldview distinctly different from one focused on using any means necessary to deliver accounting cost reductions. This worldview applies to service firms as well as manufacturing firms.5

What is the key mechanism for analyzing problems, evaluating proposed changes, overcoming implementation obstacles, and developing employees' problem-solving skills? Lean practitioners use the A3 report (named for the designation of a standard 11 x 17 piece of paper displaying the report).6 The A3 report has been developed as a specialized language to describe the problem, focus on root causes, and outline a proposed solution, including implementation steps. A3 reports are an integral part of kaizen workshops that implement targeted improvements and gemba, that is, see for yourself in order to accurately perceive a problem in the workplace.

Lean Thinking, as practiced by preeminent firms like Toyota and Danaher, is best understood not as a set of tools (e.g., inventory reduction) but as a knowledge-building culture that continuously purges waste (including time) throughout a product's value stream. Such a culture does not rely on managers' “skill” in firefighting and workarounds to “fix” problems. Lean managers are skilled at asking the right questions. Lean employees learn by solving problems as part of a cognitive process that Toyota calls kata—a pattern of thinking and behaving, which is described by Mike Rother, a leading expert on Toyota's culture:

There is a human tendency to desire and even artificially create a sense of certainty [worldview]. It is conceivable that the point here is not that we do not see the problems in our processes, but rather that we do not want to see them because that would undermine the sense of certainty we have about how our factory is working. It would mean that some of our assumptions, some things we have worked for and are attached to, may not be true.

Toyota's improvement kata involves teaching people a standardized conscious “means” for sensing the gist of situations and responding scientifically. This is a different way for humans to have a sense of security, comfort, and confidence. Instead of obtaining that from an unrealistic sense of certainty about conditions, they get it from the means by which they deal with uncertainty. This channels and taps our capabilities as humans much better than our current management approach, explains a good deal of Toyota's success, and gives us a model for managing almost any human enterprise.7

In the workplace the focus is on a target condition, that is, how a process operates to produce a specified outcome. By achieving the target condition, waste is eliminated—a highly disciplined, scientific approach. The essence of kata is rigorous experimentation and learning that becomes a way of life and supports a knowledge-building culture.

Win-win relationships between management and employees rooted in knowledge building are the foundation for a highly productive culture—the truth of that assertion is evidenced by the Fremont plant story.

In 1984, General Motors reopened an idle plant in Fremont, California, which had been well known for producing low-quality cars, coupled to low employee morale, high absenteeism, and frequent strikes. Not surprisingly, the Fremont plant was GM's worst-performing plant. This plant then became a joint venture with Toyota—New United Motor Manufacturing, Inc. (NUMMI). GM wanted to learn about Toyota's lean production system and also improve manufacturing to deliver high-quality small cars. One of the Japanese managers assigned to train American production supervisors in the NUMMI plant was Susumu Uchikawa. He explained that he did not want to hear “No problem” when asked about production. “No problem is a problem! Managers' job is to see problems!”8

Toyota hired 85% of the employees who previously produced GM's lowest-rated quality cars. These employees appreciated Toyota's noted respect for people and lean principles of standardized work, training, mentoring, and problem solving without blaming anyone.9

After a year, NUMMI was GM's best-performing plant with the highest-rated quality. A firm's long-term success in delivering quality products to customers depends upon management taking concrete actions that give employees a reason to participate in sustaining a win-win relationship. As part of the NUMMI contract with the United Auto Workers union, Toyota proposed eliminating the onerous job classifications that contravened the lean problem-solving approach of employees working in teams. The union agreed and Toyota willingly specified in the contract that during hard times, management salaries would be cut first, along with other actions taken to avoid layoffs. When demand for the plant's Chevy Novas sharply declined with sales plummeting 30% below expectations, Toyota changed the models produced in the plant and brought previously outsourced work into the plant. There were no layoffs and management further cemented a win-win relationship with employees. The pragmatic theory of the firm and Lean Thinking share a belief that a firm's success is tied to the people who build the knowledge that ultimately drives the value created for customers.

Regrettably, GM's top management and board failed to build upon NUMMI's success, which speaks volumes about the need to avoid a stifling bureaucratic culture that stymies adaptation to needed change. During the 2007–2009 recession, NUMMI was abandoned and the plant was later sold to Tesla Motors.

NUMMI plainly shows the importance of respect for employees, which is an integral part of employees' continual learning, personal growth, and the satisfaction of experiencing a productive work life. Should we label this an HR (human resources) issue, a culture issue, a productivity issue, or perhaps even a moral issue? It's hard to settle on a single word. Perhaps a more useful approach is to rely on the pragmatic theory of the firm, which assumes the firm is a holistic system managed to sustain win-win relationships with all of the firm's stakeholders, especially employees.

THE THEORY OF CONSTRAINTS

Eli Goldratt's The Goal: A Process of Ongoing Improvement became a mega bestselling book. This was followed by a series of business books, videos, seminars, and a worldwide consulting organization to communicate the continual advancements of his work which was named the Theory of Constraints (TOC). It is rooted in comprehensive cause-and-effect thinking to solve problems (including overcoming obstacles to implementation) and generate substantial performance gains. TOC began as a production and scheduling management tool for manufacturing plants. This led to addressing ongoing improvements when constraints move outside of production and was applied to businesses other than manufacturing.

Due to a continual stream of notable insights that he generated over his lifetime, many labeled Goldratt a genius. He disagreed and maintained that his insights naturally flowed from a rigorous application of cause-and-effect analysis rooted in his training as a physicist. He would dissect seemingly complex business problems and avoid compromises in order to create breakthrough solutions that retrospectively seemed so simple. Goldratt typically described his approach as just commonsense. The hallmark of TOC is giving top priority to identify and fix a system's key constraint. The constraint is the roadblock, but also the maximum leverage point, to achieving big performance gains.

Figure 3.3 positions TOC in the context of the knowledge-building loop, as was done for Lean Thinking in Figure 3.2.

FIGURE 3.3 The Theory of Constraints

Early on, Goldratt criticized the spurious assumption that a resource standing idle is a “cost” reflective of waste and inefficiency. He argued that a system, such as a manufacturing plant, is optimized by a work pace that accommodates the processing speed of the key constraint. Avoiding work-in-process inventories due to overproduction resulting from keeping resources “working” at all times is not original to Goldratt. Henry Ford limited the space for work-in-process inventories in his automotive manufacturing lines. The Toyota Production System controls flow via a Kanban mechanism and skill in reducing setup times for different parts.

TOC involves systems thinking to avoid dealing with problems in isolation which frequently occur due to a firm being organized around separate activities. A system approach focuses on achieving the goal of the system and facilitates the discovery of root causes of undesirable effects. In Goldratt's words:

The secret of being a good scientist, I believe, lies not in our brain power. We have enough. We simply need to look at reality and think logically and precisely about what we see. The key ingredient is to have the courage to face inconsistencies between what we see and deduce and the way things are done. This challenging of basic assumptions is essential to breakthroughs. Almost everyone who has worked in a plant is at least uneasy about the use of cost accounting efficiencies to control our actions. Yet few have challenged this sacred cow directly. Progress in understanding requires that we challenge basic assumptions about how the world is and why it is that way. If we can better understand our world and the principles that govern it, I suspect all our lives will be better.10 (italics added)

TOC's process of ongoing improvement consists of five steps.

- Identify the system constraint.

- Exploit the constraint through quick improvements using existing resources.

- Subordinate the nonconstraint activities to support further improvement of the key constraint.

- Elevate the constraint through actions that finally break the constraint.

- Repeat the process because after the original constraint is broken, the key constraint has moved elsewhere.

These steps represent cycles through the knowledge-building loop with preponderant focus on actions and consequences. TOC users are wary about sophisticated computer algorithms to optimize local efficiencies instead of optimizing the overall system. They focus on how the key constraint changes over time. For example, solving a major constraint in production can easily enable much higher output, thereby possibly moving the key constraint to marketing. Identifying such a shift is the purpose of the above Step 5.11

Goldratt devised the TOC Thinking Processes as a language of cause and effect (logical trees) that facilitated answers to three questions: (1) what to change, (2) what to change to, and (3) how to cause the change. The Thinking Processes helps analyze systems composed of myriad complex interactions. Importantly, the robust and comprehensive TOC logic enables hypothesis testing without the need for real-world experiments. Goldratt summarizes:

This process of speculating a cause for a given effect and then predicting another effect stemming from the same cause is usually referred to as effect-cause-effect.… Every verified, predicted effect throws additional light on the cause. Oftentimes this process results in the cause itself being regarded as an effect thus triggering the question of what is its cause. In such a way, a logical tree that explains many vastly different effects can grow from a single (or very few) basic assumptions. This technique is extremely helpful in trying to find the root cause of a problematic situation. We should strive to reveal the fundamental causes, so that a root treatment can be applied, rather than just treating the leaves—the symptoms.

Thus one of the most powerful ways of pinpointing the core problems is to start with an undesirable effect, then to speculate a plausible cause, which is then either verified or disproved by checking for the existence of another type of effect, which must stem from the same speculated cause.

By explaining the entire process of constructing the Effect-Cause-Effect logical “tree” we have a very powerful way to persuade others.12 (italics added)

TOC's extreme focus on the key constraint results in less attention (compared to Lean) to firm-wide employee learning and continuous interaction between managers at different levels. On one hand, an inefficient firm using a push production system with big buffers (e.g., inventories) is ripe for an immediate boost in performance via the introduction of TOC. On the other hand, an efficient firm with many years of experience using lean principles, and operating with a pull scheduling system, is not as susceptible to push-derived bottlenecks. Moreover, the efficient lean firm adds capacity in small, manageable increments as opposed to large capital expenditures typical of a batch manufacturing firm that can contribute to future bottlenecks.

TOC's Thinking Processes is a powerful language that enables fast and effective traversing of the knowledge-building loop. Goldratt was skilled in overcoming subtle constraints imposed by the use of common words.13 The conventional view is that strategy exists at the highest level of a firm where management and the board agree on an overall direction that can distinguish the firm from its competitors. And tactics exist at lower levels where activities are shaped consistent with achieving success for the strategy. In contrast, Goldratt first defined strategy as the answer to the question: What for? and tactics as the answer to the question: How to? Second, Goldratt concluded that strategy and tactics should exist in pairs.

This arrangement is particularly useful for analyzing innovation—a new value proposition for better serving customers or a core strategy for a startup or ongoing firm. While some scholars of entrepreneurship make sweeping generalizations for an extreme focus on a process that accepts failures as long as one fails fast, TOC advocates argue for early and deep logical analysis to scrutinize the critical assumptions involved with delivering value.

Big ideas often exploit what has already been discovered but not fully exploited. The advantages of focusing on a system's key constraint to improve performance were known before Goldratt popularized the concept. Keep in mind that advancements invariably involve knowledge building. As for TOC, the Thinking Processes are the primary means to facilitate knowledge building. Once again, we see that knowledge building and value creation are opposite sides of the same coin.

ONTOLOGICAL/PHENOMENOLOGICAL MODEL

Werner Erhard is uniquely skilled in connecting ideas in new ways that provide insights about human behavior attuned to practical needs. His work has been applied to individual, organizational, and social transformations (www.wernererhard.com) and is the foundation for a distinctly different approach to leadership keyed to performance improvement via an ontological/phenomenological model (OPM), which he and his colleagues have developed in recent years. This model is gaining worldwide attention and is packaged as course material for classroom use.14

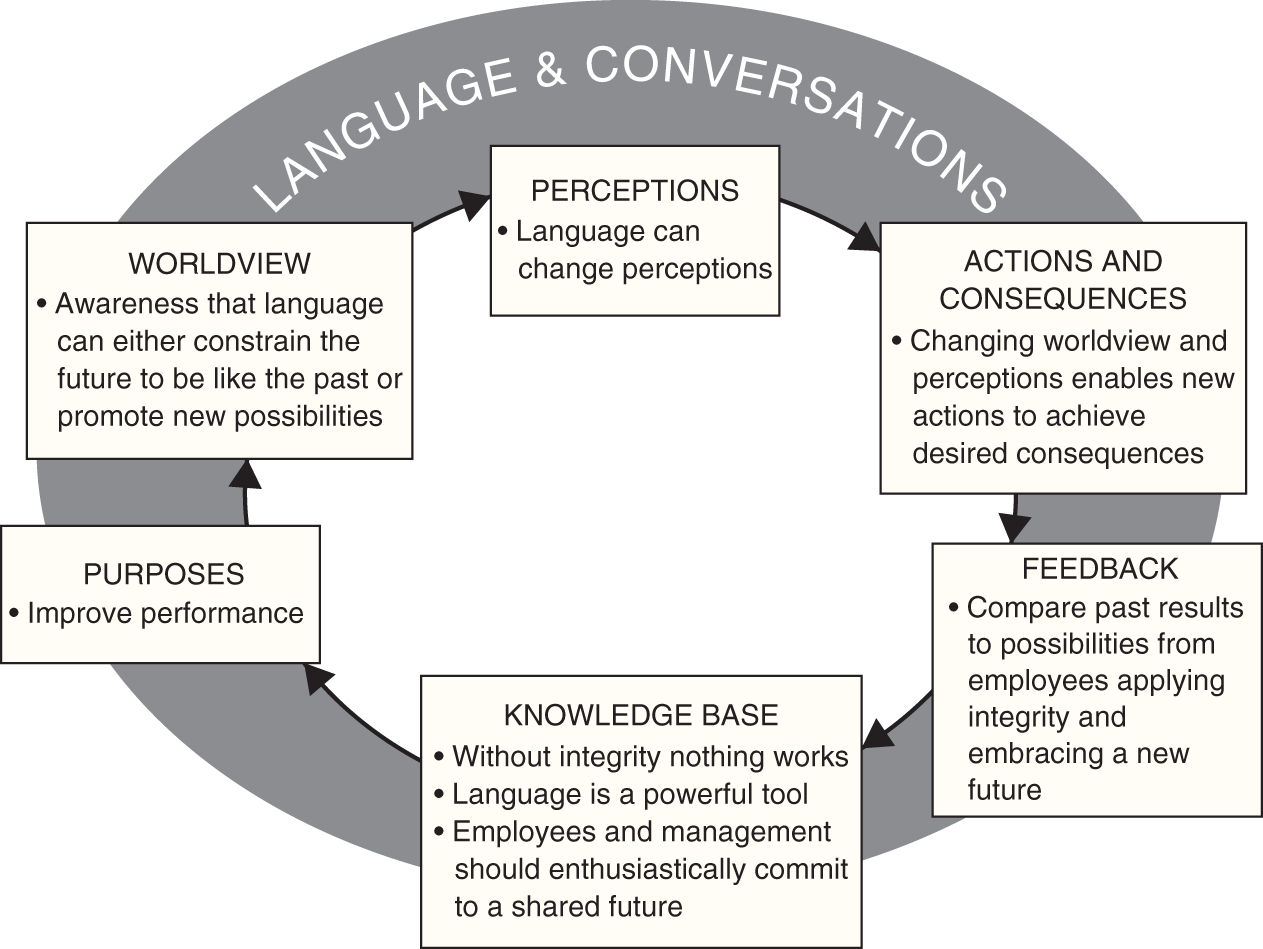

FIGURE 3.4 OPM framework

The name of this model seems to suggest that it is abstract, steeped in philosophy, and a tough challenge to comprehend. Not so. The knowledge-building loop (Figure 3.4) neatly packages the key OPM components which are summarized as follows:

Integrity, authenticity, and being committed to something bigger than oneself form the base of “the context for leadership,” a context that once mastered, leaves one actually being [ontology] a leader. It is not enough to know about or simply understand these foundational factors, but rather by following a rigorous, phenomenologically [direct experience] based methodology, students have the opportunity to create for themselves a context that leaves them actually being a leader and exercising leadership effectively as their natural self-expression.15

As shown in Figure 3.4, OPM includes the following strongly held beliefs: without integrity nothing works; language is a uniquely powerful tool; and a person's worldview about the future is not etched in stone, rather a person can see the future as a repeat of the past or a future with potential for new and rewarding experiences. OPM logic begins with performance being driven by action. And action is closely connected with how a situation occurs for an individual. This connection is viewed as the source for performance improvement. Moreover, language (including what is said and unsaid) can be used to affect how situations occur, thereby impacting performance. OPM clearly has a sharp focus on changing how individuals perceive the world, which typically is missing from management's “to do” list for achieving performance gains.

A key distinguishing feature is OPM's lack of concern for searching for cause-and-effect relationships in the work environment as typically seen in approaches to improve performance. Instead, the focus is on how employees' performance correlates with their perceptions.

Action is a correlate of the way the circumstances on which and in which a performer is performing occur (show up) for the performer.… “Occur” does not require the performer to pay any attention to, think about, understand, analyze, or interpret that which is registered.

The world we interact with (act on and by which we are acted on) is the so-called objective world. However, while most of us don't give any thought to it, in a fundamentally important sense the world we actually respond to and react to is the world as we perceive it, what we have termed the occurring world.

If we are dealing with life as lived, or performance as lived (the perspective of this new paradigm of performance), seeing and treating the objective and occurring worlds from the perspective of them being two distinct and separate worlds obscures the way we actually live life and live performance.… The as-lived perspective allows access to the source of performance.16 (italics in original)

OPM lays a path for management to deliver effective leadership and achieve significant performance improvement. The key is to gain employee commitment to a future distinctly better than the past. Consequently, the envisioned future becomes the context for the present so that employee perceptions change, enabling new possibilities to emerge. However, a necessary ingredient for sustained superior performance is integrity (i.e., keeping one's word). The importance of integrity is summarized by Michael Jensen:

Integrity is important to individuals, groups, organizations, and society because it creates workability. Without integrity, the workability of any object, system, person, group or organization declines; and as workability declines, the opportunity for performance declines. Therefore, integrity is a necessary condition for maximum performance. As an added benefit, honoring one's word is also an actionable pathway to being trusted by others.17

In their book, The Three Laws of Performance, Steve Zaffron and Dave Logan emphasize that individuals function with an implicit view of the future that shapes how the world occurs to them and thereby impacts their performance. So, to rewrite their default future requires the use of language involving promises and commitments from and to the individual. As previously noted, this necessitates leadership attuned to how employees perceive the firm in general, and their work environment in particular, which highlights the need for a purpose of the firm that employees feel is a win-win partnership.

Using the knowledge-building loop as a general-purpose analytical template facilitates comparison of OPM to other improvement approaches, such as TOC. For example, TOC's Thinking Processes, with their extensive logical diagrams, focuses on cause and effect, enabling users to discover root causes of problems. This clarity as to what needs to be done (and why) can change how the world is perceived. This directly ties into a critical takeaway of OPM, that is, language is the means for employees to reset their worldviews by purging the tendency to see the future as an extrapolation of the status-quo past. TOC's persuasive logic—the language of logical trees—can replace skepticism about living a new reality with a logically sound belief that a new environment of substantial performance gains is realistically achievable.

Lean Thinking, TOC, and OPM rely on managers who fully understand the payoffs from continual knowledge building. Such a knowledge-building culture depends upon having the right people on board for key leadership positions. Ram Charan, Dominic Barton, and Dennis Carey recommend elevating human resources (HR) to the same level as finance with high-level decision-making guided by the CEO, the CFO, and the CHRO (chief human resources officer). They emphasize the importance of talent, especially for what they call the 2 percenters who create disproportionate value:

Most executives today recognize the competitive advantage of talent, yet the talent practices their organizations use are vestiges of another era. They were designed for predictable environments where lines and boxes defined how people were managed. As work and organizations become more fluid—and business strategy comes to mean sensing and seizing new opportunities in a constantly changing environment, rather than planning for several years into a predictable future—companies must deploy talent in new ways. In fact, talent must lead strategy.18

The way that key employees are compensated should ideally be linked to the creation of long-term value. Relevant to this point is a study of managers responsible for corporate R&D. No relationship was found between short-term incentives and measures of innovation. However, among firms with centralized R&D organizations, “more long-term incentives are associated with more heavily cited patents, more frequent awards, and patents of greater originality.”19

INNOVATION

Ideas about innovation range from proposals that lack empirical support but have gained shelf space in bookstores with catchy titles describing “the keys to creativity” to empirically grounded, helpful proposals such as design thinking. Businesspeople who embrace design thinking tend to mimic the practices of top-rated design firms like IDEO. Highly skilled designers are extraordinarily skeptical of initial perceptions as to what constitutes the “design problem” and apply multiple ways of observing the situation while questioning the validity of existing assumptions. A hallmark of design thinking is building prototypes of proposed design solutions. Prototypes are crude but function well to quickly generate feedback that either supports or negates a design idea. This is similar to startup firms that focus intently on quickly proving or disproving the core assumptions about their business model and learning more about their target customers.

Invariably when discussing innovation, the question arises as to how to achieve the “Aha!” moment—that novel solution or big idea that can eliminate a problem or even invent a new future. Is this basically analysis and brainstorming? Not really, as William Duggan writes:

Neuroscience has overturned that old [split brain] model of the brain. We now know that analysis and creativity are not two different functions on two different sides of the brain. In the new model—called learning and memory—analysis and creativity work together in all modes of thought. You cannot have an idea without both.

The new science of learning-and-memory reveals at last how creative ideas form in the mind. When you do something yourself or learn what someone else did, those details go into your memory. When you face a new situation, your brain breaks down the problem into pieces and then searches through your brain for memories that fit each piece. It then makes a new combination from those pieces of memory. The combination is new, but the elements are not. These three steps—break it down, search, combine—are very different from the two conventional steps of analyze and brainstorm.20

Innovation in the firm can be categorized as process insights, performance-improving insights, and scale insights.21 The previous descriptions of TOC and Lean Thinking highlight how process insights are developed and implemented. Although one specific process improvement may provide a minuscule gain to the overall productivity of a system, the continual generation of process insights can aggregate to substantial performance gains. Arranging tools on an assembly line to minimize the steps taken by employees is one example. Absent such continual improvement, a process degrades and eventually becomes a drag on the firm's competitive position.

Performance-improving insights add functionality to products, making products easier to use, and ideally distinguish them versus competitors' products. These insights typically dominate management's priority lists and sustain cash flows from the firm's existing assets.

Investing in new business ideas may lead to scale insights. These insights are breakthrough ideas that create revolutionary products and services and also new business models of exceptional effectiveness such as Amazon's Internet platform. Scale insights not only bring unique value to customers but also spawn ancillary business opportunities and large-scale growth in new, meaningful jobs. Consider job creation that evolved from the introduction of railroads, automobiles, and intermodal freight containers, each resulting from especially important scale insights involving transportation.

Management and the board should continually invest for the future even if such investments are incompatible with, or at times even compete with, the firm's existing assets. Therefore, innovation involves an organizational structure consistent with knowledge building and insightful feedback. This is not a new concept but merely a commonsense conclusion consistent with the long-term track records of highly successful firms.

As the Old Economy, focused on physical assets and local manufacturing, is replaced by the New Economy with globalization, intangible assets, and Internet-based businesses, many people are left behind, looking for new jobs. So, how does innovation impact jobs created and lost? One answer is that entrepreneurs start firms and create jobs in parallel with the commercial success of their ideas. Meanwhile, mismanaged firms lacking a viable innovation culture continually focus on cutting costs as a means to improve profitability, and failing/bankrupt firms fire their employees. It follows that economic policy should eliminate regulations that constrain entrepreneurs from starting new businesses since startups are such a fertile ground for breakthrough ideas.

RESOURCE ALLOCATION

As firms grow larger and more mature (earning approximately cost-of-capital economic returns or perhaps lower), management tends to focus exclusively on near-term cash flows and maintaining or improving their competitive position and market share. This translates into improving the performance of existing products. In this environment, opportunities for new products or services can be analyzed and easily rejected if they require capabilities not currently available. Worse, management with a worldview focused in the extreme on improving existing products can become so insulated that they are unable to perceive emerging opportunities, which never even get to the analysis stage. For example, on the road to bankruptcy, Eastman Kodak produced a significant inventory of patents emblematic of their R&D proficiency. However, alongside this technical skill for innovation, management created a bureaucratic culture that assumed business-as-usual would produce success in the future. For example, management repeatedly forecasted that its cameras and film would maintain a wide leadership over digital photography. One forecast for the year 2020 was that the photography market would be 30% digital and 70% traditional film where Kodak was dominant.22 Management with a worldview rooted in never-questioned assumptions will surely fail to get useful feedback about a changing environment and will lose the opportunity to adapt early to a new world.

Innovation is about adapting to, and sometimes leading, change which involves the smart allocation of resources. Some existing business units of a firm may have degrading prospects due to competitors with significant comparative advantage or declining long-term customer demand. Business-as-usual investments in these business units should be avoided. Easy to say. Yet the history of large firms that have failed illustrates a sustained business-as-usual mindset toward investments similar to Eastman Kodak.

At times, concern with market valuation is mislabeled as short-termism that lacks concern for nonshareholder stakeholders. But this can miss the fundamental point that long-term value creation benefits from management's use of the following economic criterion for making decisions: cash outlays need to earn a return-on-investment (ROI) that at least equals the cost of capital consumed. A more refined version of this criterion used in financial analysis is that outlays must have an expected positive net present value (NPV). Application of this criterion is often difficult, but in principle it is the right path to make best use of society's scarce resources.

Put differently, what should be management's decision process for the following types of proposed outlays: (1) decrease product prices; (2) increase all employees' salaries; and (3) hire the unemployed who live in the vicinity of a firm's production facility? Each proposed outlay benefits a stakeholder of the firm—customers, employees, and the local community. A stand-alone criterion of stakeholder benefit clearly does not work because the answer is always yes. Management needs the NPV criterion as a guidepost in order to deliver sustainable, long-term, economically sound benefits to the firm's stakeholders.23

A holistic system (Figure 3.1) promotes analysis of interrelationships of a firm's key components. How work is organized, for example, can impact resource allocation via acquisitions, which in turn impacts firm valuation. Art Byrne, former CEO of the Wiremold Company, a classic lean success story, noted that inventory is “sleeping money” that can be used to “free up a lot of cash that is currently being wasted … that can be reinvested in new products, new equipment, or acquisitions that will help expand our market share.” He emphasized that the typical reason for big inventories in a manufacturing plant is due to lengthy setup times for switching a workstation to manufacturing a different part. That lengthy setup times are an unfortunate reality is a spurious assumption according to skilled lean practitioners. For example, Wiremold employees reduced setup times for injection molding machines from 2.5 hours to 2 minutes and a rolling mill from 14 hours to 6 minutes. These extraordinary improvements in setup times mirror Toyota-style manufacturing efficiency.

Order-of-magnitude reductions in setup times was a necessary step in achieving and sustaining large inventory reductions that funded Wiremold's acquisitions. Note that expertise in lean manufacturing, which is rooted in knowledge building, was the critical ingredient in doing more with less and improving the economic returns in Wiremold's core business. Moreover, this skill in manufacturing was then extended to inefficiently managed firms which were acquired. The result was a value-creation acquisition strategy grounded in Wiremold's knowledge-building proficiency. This ties into a prediction of the pragmatic theory of the firm: in today's economy, acquisitions that exploit or extend a firm's knowledge-building proficiency tend to create greater long-term shareholder value versus acquisitions based on a cost reduction/synergy rationale.

Our lead times went from 4–6 weeks to 1–2 days. We were growing and gaining market share. We freed up over half our floor space and used the cash from the inventory reduction to purchase 21 companies over the course of about 9 years.… We increased operating income by 13.4x and enterprise value by just under 2,500% over these same 9 years.

For acquisitions this focus on increasing inventory turns was a home run. Not only did we free up the cash to do the acquisitions in the first place but most of them were only turning inventory about 3x.… We knew we would be able to get those turns up to 6x by the end of the first year and to about 10x by the end of the third year. Combined with the rest of our lean implementation we were able, for the most part, to get all of our purchase price back in cash by the end of the third year and then those companies were contributing cash towards the next new product or the next acquisition.24

Because their workplace is organized by value streams and oftentimes a cellular layout so that products (or services) flow in response to the pull of customer orders, lean employees are better able to see the entirety of a product or service, to identify waste, and to receive more useful feedback about the actions and consequences of their work activities (learning). Lean employees have an opportunistic worldview—problems are welcomed as illustrated in Figure 3.2. This performance-enhancing worldview was transferred to employees of firms that Wiremold acquired.

The long-term performance of Wiremold illustrates how a firm can be managed as a holistic system of interrelated activities. The firm's expertise in Lean Thinking led to value-creating acquisitions as a critical component of its resource allocation strategy. This way of thinking sharply differs from short-termism that views financial performance as something to be engineered by cutting costs and doing whatever it takes to hit short-term accounting targets—absent any meaningful mindset about building long-term value and respect for employees who ultimately determine performance.

The above example shows how substantial performance gains for a firm are mutually beneficial to customers, shareholders, employees who are continuously increasing their human capital (problem-solving skills), and society in general. Understanding the histories of firms like Wiremold illustrates how analysis of the microeconomics of a firm provides a bottom-up understanding of macroeconomics as discussed in Chapter 1.

THE KEY CONSTRAINT IN SUSTAINING A KNOWLEDGE-BUILDING CULTURE

Let us focus on one of society's most important aims: large-scale economic benefits. As previously noted, the three complementary managerial approaches reviewed in this chapter are fundamentally concerned with improving performance via fast and effective traversing of the knowledge-building loop. This suggests that a scale insight—consistent with boosting dynamism as recommended by Edmund Phelps—would be to figure out how to remove the key constraint that blocks firms from effectively implementing a knowledge-building culture in the spirit of top-performing lean firms. Recall the previous quote from Mike Rother about how the Toyota Production System enhances employee ability to deal with uncertainty “channels and taps our capabilities as humans much better than our current management approach.” The key constraint is that too many firms use a management approach that does not embrace purpose, respect for people, and continuous experimentation and learning at all levels of the firm to the extent needed to sustain a knowledge-building culture and a highly productive and fulfilling way of life for the firm's employees.

What are the essential tasks involved in breaking this key constraint? Some possibilities can be gleaned from the history of the Danaher Corporation, generally acknowledged as America's preeminent lean firm. The Danaher story is another concrete example of how microeconomics focused on firm performance connects to macroeconomics.

The fundamental value-creation driver for Danaher is its knowledge-building proficiency with emphasis on experimentation and learning. The label “Lean” can be misleading when it is used to represent lean tools (e.g., kaizen) giving the impression that implementation of lean tools is enough to achieve sustained high performance. Danaher labels its managerial approach the Danaher Business System (DBS) whose purpose is to improve innovation, quality, delivery, and cost to the firm's customers (i.e., value creation). DBS is Danaher's version of the Toyota Production System.

Steven and Mitchell Rales were experienced financial dealmakers when they began in the early 1980s to build Danaher into a preeminent high-performance firm. One of their early acquisitions was Jake Brake, which was the first American firm to implement Lean Thinking. Based on the performance gains at Jake Brake, the Rales brothers insisted that everyone commit to DBS as a way of life at Danaher extending from top management to the factory floor, including all of the firm's activities, not just manufacturing.

All of Danaher's top managers are exceptionally skilled in lean know-how and regularly teach classes to employees. This contrasts with the many situations where lean is not sustained in firms due to a lack of involvement with top management. Furthermore, Danaher's operating companies use extensive real-time data metrics for both process variables and financial variables in order to provide continuous hard-nosed, factual feedback to improve performance.

As to hiring outside managers, care is taken to avoid people with “bad habits,” that is, those “skilled” in achieving results in ways inconsistent with DBS and sustainable business processes but typical of many current management cultures. Danaher acquires firms that have solid long-term prospects but typically lack operational efficiency in ways that the implementation of DBS can greatly improve. Danaher takes pride in being a learning machine, and that extends to insights gained from acquired firms that are then transferred to other Danaher operating companies. In 2016, Danaher reorganized into two separate businesses—Fortive Corporation for industrial businesses and Danaher Corporation for science and technology businesses.

What prevents CEOs from following Danaher's lead for delivering sustained high performance? Let's begin with the notion that context matters. Typically, CEOs are in their leadership positions because of their past success in working in firms with hierarchical, command-and-control organizational structures. They demonstrated skill by taking charge and producing results that fit the command-and-control structure. Instead of systematic experimentation for dealing with the future, the typical environment was to lay out a plan and then do whatever is needed to meet or exceed the planned accounting targets for that part of the system for which they had responsibility. Moreover, if their educational background includes an MBA, their business school experiences have likely further emphasized specialized, quantitative planning and control.

These experiences differ markedly from work experiences within an organizational structure rooted in a knowledge-building culture that relies less on authoritative control and more on lower-level employees taking responsibility to solve problems and continually improve processes. Such a culture encourages experimentation and feedback that can reveal root causes of problems and obsolete assumptions at all levels of the organization while encouraging system thinking to cut across activities and optimize overall system efficiency.

The hierarchical command-and-control organizational structure has deep roots and is difficult to change. Of the firms that attempt to transition and sustain Lean Thinking across all their key activities, a reasonable estimate is that 4% to 7% have succeeded in the past.25 However, the ongoing debate about capitalism discussed in Chapter 7 will draw attention to key elements of the firm's purpose: vision, survive and prosper, win-win partnerships, and taking care of future generations. This reexamination of the role of the firm in society will likely accelerate a transition to a holistic purpose-based view of the firm which also involves a transition away from the conventional hierarchical command-and-control structure. A holistic purpose-based view of the firm improves upon the maximizing-shareholder-value purpose so prevalent in mainstream finance. The next chapter focuses on a key component of the pragmatic theory of the firm—the life-cycle framework for connecting a firm's long-term financial performance to its market valuation.

NOTES

- 1 Gary Hamel, 2012, What Matters Now: How to Win in a World of Relentless Change, Ferocious Competition, and Unstoppable Innovation. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- 2 Dominic Dodd and Ken Favaro, 2007, The Three Tensions: Winning the Struggle to Perform without Compromise. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- 3 Taiichi Ohno, 1998, Toyota Production System: Beyond Large-Scale Production, New York: Productivity Press, p. ix.

- 4 James P. Womack and Daniel T. Jones, 2003, Lean Thinking: Banish Waste and Create Wealth in Your Corporation, 2nd ed., New York: Free Press, p. 10.

- 5 For an insightful description of the learning and leadership involved with transforming a medical practice into a lean organization, see Sami Bahri, 2009, Follow the Learner: The Role of a Leader in Creating a Lean Culture. Cambridge, MA: The Lean Enterprise Institute.

- 6 John Shook, 2008, Managing to Learn: Using the A3 Management Process to Solve Problems, Gain Agreement, and Lead. Cambridge, MA: Lean Enterprise Institute.

- 7 Mike Rother, 2010, Toyota Kata: Managing People for Improvement, Adaptiveness, and Superior Results. New York: McGraw Hill, pp. 101 and 165.

- 8 John Shook, 2010, “How to Change a Culture: Lessons from NUMMI,” MIT Sloan Management Review 51(2): 63–68.

- 9 John P. Kotter and Dan S. Cohen, 2002, The Heart of Change. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Business Review Press, p. 2, notes: “Changing behavior is less a matter of giving people analysis to influence their thoughts than helping them to see a truth to influence their feelings.”

- 10 From the Introduction to the first edition of Eliyahu M. Goldratt, 1984, The Goal: A Process of Ongoing Improvement. Great Barrington, MA: North River Press.

- 11 James F. Cox III and John Schleier, Jr., eds., 2010, Theory of Constraints Handbook. New York: McGraw Hill.

- 12 Eliyahu M. Goldratt, 1990, What Is This Thing Called Theory of Constraints and How Should It Be Implemented? Great Barrington, MA: North River Press, pp. 32–33.

- 13 For examples in business of the role of language in masking obsolete assumptions, see Bartley J. Madden, 2014, Reconstructing Your Worldview: The Four Core Beliefs You Need to Solve Complex Business Problems. Naperville, IL: LearningWhatWorks.

- 14 Werner Erhard, Michael C. Jensen, Steve Zaffron, and Jeri Echeverria, 2017, “Course Materials for: Being a Leader and the Effective Exercise of Leadership: An Ontological/Phenomenological Model,” SSRN abstract=1263835.

- 15 Scott Snook, Nitin Nohria, and Rakesh Khurana, 2012, The Handbook for Teaching Leadership: Knowing, Doing, and Being. Los Angeles: Sage Publications, p. xxiv.

- 16 This quote is from pages 49 and 52 of a comprehensive presentation of the OPM framework, Werner Erhard and Michael C. Jensen, 2010, “A New Paradigm of Individual, Group, and Organizational Performance.” SSRN Working Paper, abstract=1437027.

- 17 Michael C. Jensen, 2009, “Integrity: Without It Nothing Works,” Rotman: The Magazine of the Rotman School of Management, Fall: 16–20.

- 18 Ram Charon, Dominic Barton, and Dennis Carey, 2018, Talent Wins: The New Playbook for Putting People First. Boston, MA: Harvard Business Review Press.

- 19 Josh Lerner and Julie Wulf, 2007, “Innovation and Incentives: Evidence from Corporate R&D,” Review of Economic and Statistics 89(4): 634–644.

- 20 William Duggan, 2013, Creative Strategy: A Guide for Innovation. NY: Columbia University Press; see pp. 98–100 for a useful critique of design thinking. Also, see Eric R. Kandel, 2007, In Search of Memory: The Emergence of a New Science of Mind. New York: W. W. Norton and Company. In 2000, Eric Kandel was awarded the Nobel Prize for his research on the physiological basis of memory storage in neurons. The insightful neuroscience research done by Jeff Hawkins provides theoretical support for the learning and memory model; see Michael S. Gazzaniga, 2008, Human: The Science behind What Makes Us Unique. New York: HarperCollins, pp. 362–371.

- 21 Clayton M. Christenson, “A Capitalist's Dilemma, Whoever Wins on Tuesday,” op-ed., November 3, 2012, New York Times.

- 22 Paul Snyder, 2016, Is This Something George Eastman Would Have Done? The Decline and Fall of Eastman Kodak Company. Self-published, CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform.

- 23 Michael Jensen, 2002, “Value Maximization, Stakeholder Theory, and the Corporate Objective Function,” Business Ethics Quarterly 12(2): 235–256.

- 24 Art Bryne, “Ask Art: Why Does Boosting Inventory Turns Matter So Much?” September 13, 2018, The Lean Post.

- 25 Art Bryne, 2007, The Lean Turnaround Action Guide: How to Implement Lean, Create Value, and Grow Your People. New York: McGraw Hill Education, p. 3.