2

KNOWLEDGE BUILDING AND FIRM PERFORMANCE

By detaching our self-image and self-worth from our beliefs, we should be more willing to stress test those beliefs instead of habitually defending them. This means that being who we are won't be tied up in maintaining a particular view, answer, opinion, or conclusion. Rather, we can define our “being” by how we think and converse. Defining everything we know as conditional—subject to change based on new evidence—can help decouple our egos from our beliefs.

—Edward D. Hess1

To be radically open-minded you must … sincerely believe that you might not know the best possible path and recognize that your ability to deal well with “not knowing” is more important than whatever it is you do know.… Radically open-minded people know that coming up with the right questions and asking other smart people what they think is as important as having all the answers … what exists within the area of “not knowing” is so much greater and more exciting than anything any one of us knows.

—Ray Dalio2

THE KNOWLEDGE-BUILDING PATH TO IMPROVED PERFORMANCE

A major theme of this book is the paramount importance of a firm's knowledge-building proficiency in determining a firm's survival and prosperity over the long term. As such, a well-grounded understanding of what knowledge building entails is essential. The beginning point is four foundational ideas about building useful knowledge that can lead to improved performance.

First, to navigate through the world effectively in an energy efficient manner, our brains have evolved to use past experience to orchestrate perceptions and to guide actions. Our perceptions of what is “out there” are shaped by past experience. We see what our brains tell us to see.

Second, we experience the world as an objective, independent reality because this is such an efficient process for our daily lives. But perhaps it is not so efficient for dealing with highly complex problems. Experiencing the world as an independent reality is compounded by the fact that language itself promotes an independent reality, including a tendency to make conclusions about cause and effect based on initial perceptions.

Third, knowledge building is an integral part of living (and working) and the source of improved performance in achieving goals. As such, improving the process for improving firm performance—whether in product design, manufacturing, strategy, or culture—depends upon creative thinking attuned to effective knowledge building.

Fourth, a model of knowledge building should provide insights and reliable guideposts not only for the firm, but also for how business and science is conducted, and for decision-making in one's personal life.

The remainder of this chapter establishes key points about building a useful and reliable knowledge base. Long-term successes and failures in business have their origin in management's skill, or lack thereof, in adapting a business model to change—skill in evaluating their assumptions about the external environment and how best to serve customers. Moreover, investors' assumptions about a firm's future financial performance guide their buy/hold/sell decisions. So, improving the process of how management and investors form assumptions that constitute what they “know” is not really a philosophical exercise, but rather a critically important prerequisite for making better decisions.

THE KNOWLEDGE-BUILDING LOOP

It is a difficult challenge to assemble quantitative data about how a firm's knowledge-building proficiency changes over time. Oftentimes, published empirical research about firm performance uses easily obtained financial data to facilitate high-powered econometric analysis favored by top academic journals in finance and accounting. This process can silently avoid important but hard-to-quantify problems that can otherwise lead to major insights. The importance of understanding hard-to-quantify phenomena, such as knowledge-building proficiency, is encapsulated in the following insight by Adelbert Ames, Jr. and his colleagues:

Those who are wedded solely to a quantitative approach are all too frequently unwilling to tackle problems for which there are no available quantitative [data] … thus limiting themselves to research impressive only in the elaborate quantitative treatment of data.… But it is often forgotten that the value of an experiment is directly proportional to the degree to which it aids the investigator in formulating better problems.3

Ames pioneered work in visual perception illustrating how progress can be achieved by focusing on important variables whose measurement requires significant creative thinking. He initiated a paradigm shift that focused on how observers participate in the perceiving process given their assumptions based on past experience. He defined perceptions as predictions that facilitate actions which can yield desired consequences. His work is central to the knowledge-building loop described below, which will be relied upon throughout this book.

Who was this man whom the great American philosopher John Dewey and the renowned British mathematician and philosopher Alfred North Whitehead referred to as a genius? Adelbert Ames, Jr. died in 1955 after creating some of the most memorable scientific demonstrations of the 20th century as part of his research on visual perception that anticipated major findings of modern neuroscience. John Dewey remarked: “It would not be possible to overstate my judgment as to the importance of your demonstrations with respect to visual perception … they bear upon the entire scope of psychological theory and upon all practical applications of psychological knowledge.”4

The Ames Demonstrations in visual perception illustrate the importance of an observer's strongly held assumptions. His most famous demonstration, still reproduced in many contemporary psychology textbooks, is the Ames Distorted Room. When viewed through a peephole with one eye, an observer perceives a normal room. However, when a person in the room walks from one corner to the other, the observer's perception of that person's height radically changes. The room fails to meet the observer's firmly held assumptions, rooted in extensive past experience, about floors being level, windows rectangular, and that bigger is closer. The inability to purge these “faulty” (i.e., for the context of the Ames Distorted Room) assumptions—even when an observer learns about the room construction beforehand—dramatically demonstrates how one participates in the perceiving process. Interestingly, 21st-century neuroscience research supports the view that an observer's assumptions facilitate the process whereby the brain perceives the present as a means to predict the future.5 Importantly, achieving outsized future performance gains may well begin with management's deep appreciation of how employees actually perceive their world at work.

In the academic literature on knowledge and the firm, there is debate about the locus of knowledge and the source of value creation. That is, should the foundational unit of analysis be the individual or a collective? Most research focuses on the social dynamics of collectives (teams, multidivisional collaborators, partnerships with universities, etc.), and the resulting knowledge is attributable to the entire organization. However, I side with the minority of researchers who emphasize the individual as the foundational unit of analysis.

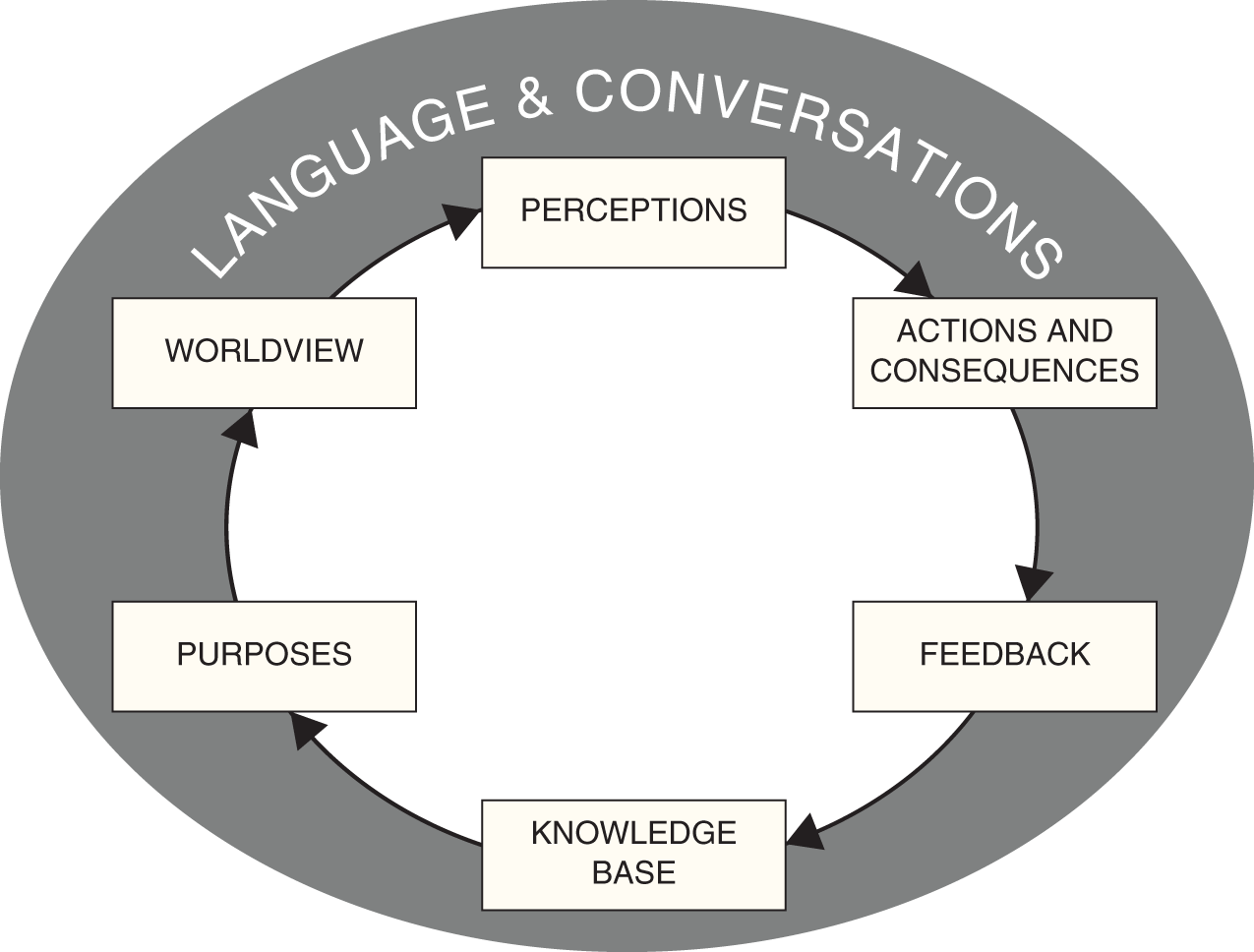

Given my choice, the first task is to construct, from the perspective of the individual, a model for building knowledge. A useful model is depicted in Figure 2.1 illustrating how we go through life by traversing a knowledge-building loop while continually learning about what actions help achieve our purposes.

Since knowledge building continually occurs as an integral part of living, there is no particular starting point for Figure 2.1. The idea is that these components are intimately connected in an ongoing process that shapes one's knowledge base. Consider these components as guideposts that help audit how we know what we think we know.

The knowledge base shown in Figure 2.1 contains assumptions of varying degrees of reliability. Some are genetically hardwired due to being especially reliable and critically important to survival. That is why we fondly touch dogs but avoid touching snakes. Many of the assumptions we rely on as true tend to be based on easy to understand cause-and-effect experiences, such as touching a very hot object and the resulting effect of pain.

Knowledge is the result of a dynamic process often involving interactions with people who individually are traversing the knowledge-building loop6 and gaining different experiences.7 The reliability of linear cause-and-effect analysis for nonliving things can lead to a false sense of confidence when the same logic is applied to complex systems, including human behavior.

FIGURE 2.1 The knowledge-building loop

Source: Adapted from Madden (2012).6

An important component of the knowledge-building loop is one's worldview which is a part of, and a result of, traversing the knowledge-building loop in order to achieve one's purposes. It represents ideas and beliefs through which we interpret and interact with the world. In general, a worldview that favors a scientific approach for deeper understanding of causality and nonlinear system complexities improves the knowing process and enables one to become more proficient in taking actions that produce desired consequences. A worldview that uses a systems lens to understand relationships among variables is more advantageous than a lens that treats variables as independent entities.

A critical component of the knowledge-building loop is perceptions. How we perceive our world is determined by how our brains function. In order to avoid sensory overload, we often operate on autopilot.8 Our brains have evolved to enable us to quickly (subconsciously) act without having to consciously analyze multiple actions and likely consequences. This improves brain efficiency while minimizing energy consumption.9 The brain stores past experiences to facilitate predictions via analogy to the past. The neuroscientist Chris Firth summarizes:

By hiding from us all the unconscious inferences it makes, our brain creates the illusion that we have direct contact with objects in the physical world.… What I perceive are not the crude and ambiguous cues that impinge from the outside world onto my eyes and my ears and my fingers. I perceive something much richer—a picture that combines all these crude signals with a wealth of past experience. My perception is a prediction of what ought to be out there in the world. And this prediction is constantly tested by action.10

In other words, we actively participate in our perceptions of the world.11 This tends to be ignored because it happens automatically. If you drive on the right side of the road and wait for an approaching car to pass before turning left, it is because you perceive the approaching car as too close. That perception is rooted in the assumption that bigger is closer. While especially reliable in our past experience, it is not always true, as can be demonstrated with visual illusions.12 Due to our participation in the perceiving process, we can unconsciously assign cause and effect to external variables even though our internal (unexamined) assumptions impact the analysis.13 A similar line of thinking is reflected in the work of Teppo Felin, Jan Koenderink, and Joachim I. Krueger asserting that reality is constructed and expressed and that this is highly important to research in the social sciences.

We see both perception and rationality as a function of organisms' and agents' active engagement with their environments, through the probing, expectations, questions, conjectures, and theories that humans impose on the world. The shift here is radical: from an empiricism that focuses on the senses to a form of rationalism that focuses on the nature, capacities, and intentions of the organisms or actors involved.14

Another critical component of the knowledge-building loop is feedback. This signifies how one's knowledge base changes due to what is learned about the consequences of actions. An existing assumption may be supported or replaced due to improved understanding. Also, feedback serves a vital role in building confidence based on evaluation of alternative hypotheses.

Given our reliance on past experiences to shape our worldview and perceptions, a problem or an opportunity can be perceived so that it easily translates into a self-assured, favorite idea (hypothesis) as the obvious way to proceed. Who hasn't experienced an individual relentlessly promoting their favorite idea, safeguarded from hard-nosed feedback that could provide useful criticisms and possibly a superior idea?

What is needed is humility (as noted in the quotes from Edward Hess and Ray Dalio at the beginning of this chapter) as to what we don't know while traversing the knowledge-building loop, which will open the door wider to deeper understanding. Therefore, feedback about alternative hypotheses is hugely important in gaining confidence about a particular hypothesis because it withstands tests to refute it while convincing others of the soundness of one's analysis and conclusions. The new experiences gained from striving for eye-opening feedback may refute one or more strongly held beliefs, change your worldview, lift constraints, and provide access to a world of greater possibilities.

The role of language and conversations is prominently displayed in Figure 2.1 due to its significant influence throughout the knowledge-building process. Language has a pervasive influence in camouflaging assumptions while greatly simplifying the world. Our use of language is so automatic that we rarely consider that language implicitly assigns an independent existence to “facts” and “things.” The English language uses noun-verb-noun construction that promotes linear cause-and-effect thinking based on variables being independent of one another. Improving the performance of complex systems, such as business firms, requires attention to systems thinking and relationships among variables. However, the words we use implicitly promote separation of subject versus object, organism versus environment, and so on.

That language is at work in how we perceive the world is important and verified, for example, by Lera Boroditsky's experiments.

I thought that languages and cultures shape the ways we think, I suspected they shaped the ways we reason and interpret information, but I didn't think languages could shape the nuts and bolts of perception—the way we see the world. That part of cognition seemed too low-level, too hard-wired, too constrained by the constants of physics and physiology to be affected by language.… I was so sure that language couldn't shape perception that I designed a set of experiments to demonstrate this.… I had set out to show that language didn't affect perception, but I found exactly the opposite. It turns out that languages meddle in very low-level aspects of perception and without our knowledge or consent shape the very nuts and bolts of how we see the world.15

Because our use of language hides critical assumptions, this presents an opportunity to analyze what is behind the words in order to see new relationships and uncover different ways of handling problems (i.e., break the constraints imposed by language). The philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein noted that “the limits of my language mean the limits of my world.”16

The analysis of language in business has important practical applications. For example, consider how often the accounting word cost is encountered in business. System thinkers question proposals to increase the efficiency of a process just because of a targeted cost reduction in one part of the system. Is there a hidden assumption in the accounting cost approach? Yes. The assumption is that system components are independent of one another, and therefore the sum of local efficiency gains for individual components should translate directly into a cumulative gain for the entire system. But system components are invariably interdependent, and gains in local efficiencies do not directly accumulate into an overall system improvement. This connects directly to the Theory of Constraints (Chapter 3), which focuses improvement on the system's key constraint in order to quickly and efficiently improve overall system performance. Otherwise, opportunities to reduce costs can be found everywhere, and the biggest leverage point (the key constraint) is not prioritized.

The knowledge-building loop helps one develop a useful toolbox to deal with today's business challenges and to gain insights about a firm's past performance. For example, Lou Gerstner became CEO of IBM in 1993, when the firm's stellar, innovative successes were only dim memories and a serious cash shortfall was putting IBM on the road to bankruptcy. The following quote from Gerstner reflects his deep understanding that the root cause of the steep decline in IBM's profits was the fundamental deterioration of IBM's knowledge-building proficiency:

When there's little competitive threat, when high profit margins and a commanding market position are assumed, then the economic and market forces that other companies have to live or die by simply don't apply. In that environment, what would you expect to happen? The company and its people lose touch with external realities, because what's happening [perceptions] in the marketplace is essentially irrelevant to the success of the company.

This hermetically sealed quality—an institutional viewpoint [worldview] that anything important started inside the company— was, I believe, the root cause of many of our problems … leading to a general disinterest in customer needs [lack of feedback], accompanied by a preoccupation with internal politics. There was a general permission to stop projects dead in their tracks, a bureaucratic infrastructure that defended turf instead of promoting collaboration, and a management class that presided rather than acted [lack of purpose]. IBM even had a language all its own.17 (italics added)

Gerstner made an important decision to revitalize the mainframe computer with CMOS technology, relentlessly communicated to employees how customer-focused teamwork was going to produce a better future, and successfully restructured IBM into a firm offering integrated solutions to customers. Throughout his tenure as CEO (1993 to 2002), he emphasized the need to “speak in plain, simple, compelling language that drives conviction and action throughout the organization.”

In this book, historical analyses are presented for a diverse group of firms. These case studies emphasize the advantages of using the knowledge-building loop to better understand fundamental causes of long-term success and failure. Seeing beyond good/bad strategies, innovative/copycat products, and management's efficiency goals, a strong case is made for the overriding, bedrock importance of a firm's knowledge-building proficiency in determining the quality of a firm's strategy, innovation, and employee spirit—and ultimately determining a firm's long-term performance. Large-scale successes and failures often result from a management worldview being either adaptive or nonadaptive. The former promotes feedback to identify obsolete assumptions, either within the firm or the industry, and related new opportunities. The latter leads to a bureaucratic culture promoting a belief that what worked well in the past must surely work well in the future.

HUMAN BEHAVIOR, CULTURE, AND FIRM PERFORMANCE

Knowledge building (learning) is an integral part of living and occurs automatically as we strive to achieve our goals. One view of behavior considers actions fundamentally as a response to a stimulus. A different view, however, is slowly gaining support, that is, living organisms have purposes and control variables that are important to them. Perceptual control theory (PCT), developed by William T. Powers, treats living organisms as being wired with a hierarchical control system intent on making our perceptions of the current state of variables we want to control match our intended state for these variables (negative feedback control). Consequently, behavior is control of perception. Whether driving a car, hiking along a trail in rough terrain, or having a conversation at work, we as human control systems automatically take actions likely to control what is important to our purposes. To understand behavior, identify a person's purposes (goals) that are especially important to him or her. The “I get it” insight is that people do not respond to stimuli; they act to oppose disturbances to their controlled variables.

The control-theory version of human nature—or the nature of organisms, for that matter—can be put succinctly. Organisms control. Whatever we see them doing, at whatever level of analysis we prefer, we see them controlling, not reacting. The old metatheory says that there is a one-way path through the organism, from cause to effect. The final effect is behavior. The new one says that there is a closed loop of action that has neither a beginning nor an end. The old concept says that behavior can be expressed as a function of independent variables in the environment. The new concept says that behavior is varied by the organism in order to control its own inputs. The old concept says that environments shape organisms. The new one says that organisms shape both themselves and their environments.18

Think of all the studies in the social sciences based on a stimulus-response mindset that are straightforward to design, to run, and to publish. However, PCT's emphasis on control variables in order to understand behavior brings difficult challenges to identify and measure these variables. As such, the influence of PCT has been slowed in part due to the inertia from the huge past investment in stimulus/response journal articles and textbooks, plus the difficulty in transitioning to PCT-type studies. Nevertheless, an awareness of PCT equips one to be skeptical of much empirical research in management dealing with incentives, culture, new product design, and much more.19

The stimulus/response mindset often appears to be reliable, but inattention to control variables can lead to inaccurate predictions, especially when context changes. One revealing instance of control involved maintenance employees in a manufacturing facility.20 Their performance was measured by the time needed to repair machines. The question for management was: How do we improve performance of the maintenance crews? Management could have used a stimulus/response mindset and perhaps offered bonuses (stimulus) for achieving especially fast repair times (response). However, management analyzed the situation more deeply and concluded that performance should be measured by the length of time between machine breakdowns. This led to improving employees' worldview and therefore how they perceived problems. Instead of doing a superficial quick fix, employees' new goal was to discover and fix the root cause of a machine's breakdown in order to control the time between machine breakdowns. This relates to the ontological/phenomenological model of performance developed by Werner Erhard and his colleagues and discussed in Chapter 3. Their model focuses on language and conversations to change how the world occurs to people (perceptions) thereby opening up new possibilities for action.

Changing an adversarial relationship between management and employees is both a big problem and a big opportunity for improved performance. Steve Zaffron, CEO of the consulting firm Vanto Group, worked with a mining company in Peru that had a strong status system putting the direct descendants of the Spaniards at the top and the Indian workers at the bottom. Different color hats communicated an employee's status. The result was that the worldview of lower status employees impaired teamwork, promoted an “us versus them” culture, and constrained performance.

As part of fundamentally restructuring the firm's management system and changing how employees perceived the world, the different color hats were discarded. The same color hats for everyone became a powerful visual language that promoted teamwork.

With that one change, the future shifted. The workers began to see their future and their role within the company completely differently—performance altered dramatically. The workers were able to see themselves as an integral, vital part of the mine's future. They were able to step outside their separate roles and experience themselves as part of a team. Few forces are as powerful in elevating a company's performance as a vision shared and owned at every level. When people take on their company's vision as their own, it becomes the generative force of the organization.21

The three steps to improve performance by changing how employees perceive the world are: (1) discover what constrains employees from fully utilizing their abilities; (2) create a way to remove that constraint in order to upgrade performance in achieving the goal of the system; and (3) effectively communicate how the change will enable employees to perform better in the future and, ideally, also improve their problem-solving skills.

Whenever the topic of human behavior and firm performance is discussed, attention is drawn to a firm's culture. This book makes the case for the overwhelming importance of a firm's knowledge-building proficiency and therefore the need for a culture that nurtures and supports knowledge building. Typically, culture is defined as certain shared beliefs about how work should be done, and what is acceptable or unacceptable behavior. Referring to Figure 2.1, the following definition is more useful in general, and in particular, better fits with the pragmatic theory of the firm.

Culture is the language and conversations of management and employees that either strengthen or weaken: (1) beliefs about how work should be performed; (2) confidence in a win-win partnership between management and employees; (3) a commitment to mentoring of employees to continually improve their problem-solving skills; and (4) employee pride in what the firm stands for in the eyes of customers. A firm's culture is manifested in the worldview of those working in the firm and impacts their perceptions of both change in the external environment and opportunities to improve performance of internal operations.22

How should management orchestrate a major change in a firm's culture? The change should be grounded in knowledge building due to its obvious tie-in to improved performance. Moreover, by continuously improving their problem-solving skills and (simultaneously) their productivity, employees achieve intrinsic job satisfaction and a justified sense of earned success. However, it is reasonable to expect that an abstract conversation about a major change in how work is to be done will elicit resistance from employees.

For example, implementation of Lean Thinking, epitomized by the Toyota Production System, involves a strikingly big change in culture for employees accustomed to conventional manufacturing processes. Managers experienced in successfully transitioning to lean processes emphasize the need for initial demonstrations of productivity gains. This enables conversations focused on pragmatic feedback about how switching to lean production methods in specific parts of a firm's manufacturing processes results in quantified performance gains, especially gains that are very substantial and not possible with the status quo manufacturing methodology. This is the type of language needed to gain commitment from employees.

ELEGANT, PARSIMONIOUS, AND RELIABLE THEORIES

Living brings continual experiences in traversing the knowledge-building loop as we expand our knowledge base and, over time, through our worldview we embrace theories about how the world works that we believe to be true. Theory construction begins with a worldview that shapes observations followed by descriptions of phenomena that lead to useful classifications. The next step is to focus on ideas about cause and effect that may change under different classifications of environmental conditions. A primary task is to identify which variables are critically important to the causal process. This is essential in order to develop a theory which can potentially be elegant, parsimonious, and reliable. For example, the pragmatic theory of the firm asserts that a firm's long-term performance is primarily the result of a firm's knowledge-building proficiency versus that of its competitors.

After a theory is crafted that may offer a superior handling of cause and effect, the next step is to systematically test the theory.23 For a specified environment, when actual results significantly diverge from predictions, any outlier observations (anomalies) offer both opportunities to better understand the limits of a theory and clues for improving the theory being tested.24 In a famous article titled “Strong Inference,” John Platt argued that focusing on excluding hypotheses (theories) is the key to efficient knowledge building in any area of inquiry. Here he comments about Pasteur shifting his research efforts to biology:

Can anyone doubt that he [Pasteur] brought with him a completely different method of reasoning? Every two or three years he moved to one biological problem after another, from optical activity to the fermentation of beet sugar to the “diseases” of wine and beer, to the disease of silkworms, to the problem of “spontaneous generation,” to the anthrax disease of sheep, to rabies. In each of these fields there were experts in Europe who knew a hundred times as much as Pasteur, yet each time he solved problems in a few months that they had not been able to solve. Obviously, it was not encyclopedic knowledge that produced this success, and obviously it was not simply luck, when it was repeated over and over again; it can only have been the systematic power of a special method of exploration.… Week after week his crucial experiments build up the logical tree of exclusions.25

Of paramount importance is the specificity of a theory or hypothesis that can enable it to be falsified so that continual learning occurs. That is, theory construction is a continual journey of traversing the knowledge-building loop in order to test and improve a theory. We benefit from awareness that language often shields faulty assumptions from needed criticism. In addition, observations are not facts etched in stone but perceptions influenced by past experience that affect our assumptive worlds.

Researchers ought to be wary of prematurely fixating on a favorite theory or hypothesis that leads them (perhaps unconsciously) to produce data favoring their preference while shunning other explanations. Consider the question of why zebras have stripes.

Tim Caro, professor of wildlife biology at the University of California at Davis, and his colleagues developed a now widely accepted explanation of why zebras have stripes.26 Five hypotheses competed to explain their existence: (1) camouflage, (2) visual confusion for attacking predators, (3) temperature regulation, (4) social function, and (5) avoidance of biting flies. Support for the biting-flies hypothesis increased as empirical feedback from traversing the knowledge-building loop yielded confirming data while investigations of the other theories yielded essentially zero empirical support.

Would the biting-flies hypothesis hold beyond the African location where the original research focused on zebras? Additional research showed that in areas heavily infested with biting flies, animals evolved with bodily stripes. Checkmark for the biting-flies hypothesis. Also, it was discovered that biting flies have visual problems when confronted with stripes. Very big checkmark. Finally, why do zebras have such pronounced stripes? The researchers argued that unlike other hooved mammals living in the same environment, zebras have especially short hair making them highly susceptible to biting flies, adding another checkmark for the biting-flies hypothesis.

The knowledge-building process provides answers while simultaneously raising new questions. For example, why do biting flies encounter visual problems due to striped surfaces? And the cycle continues.27

Keep in mind that a useful theory improves behavior, that is, thoughts and actions that help achieve our purposes. A useful theory does not necessarily contain a revolutionary concept; it may simply spotlight what we have always seen but never meaningfully noticed. The theory may seem glaringly obvious once articulated. However, a powerful theory enables us to behave confidently because new actions are rooted in a more reliable understanding of cause and effect and therefore more likely to yield desired consequences.

Consider the Theory of Jobs to Be Done crafted by Professor Clayton Christensen and his colleagues at the Harvard Business School.28 It facilitates a much deeper understanding of cause and effect for customer purchase decisions compared to a conventional analysis using customer satisfaction surveys. The theory's fundamental insight is rooted in language, specifically “buy” versus “hire.” In contrast to simply using a product after you buy it, the new concept implies that you hire a product to make progress on a job that you want done. This is a new way of thinking that improves upon simply comparing a product to competing products. The theory motivates product developers to better align a product with the job customers are trying to accomplish.

So obvious you may say. But this big idea can forcefully impact the actions of innovators in order to achieve their desired consequences. For example, the design of new features of a product (or service) can lead to incremental advantages versus competitors' products and modest growth in sales. However, configuring a product to help customers make significant progress on needed jobs can lead to especially large growth in sales.

The popular QuickBooks accounting software, developed by the financial software firm Intuit, offers an insightful example of the usefulness of the Theory of Jobs to Be Done. QuickBooks initially generated remarkable sales growth even though it sold at a substantial premium. The competing software packages provided an ostensibly huge advantage in terms of comprehensive functionality versus the slimmed-down QuickBooks. Note that the Intuit product clearly enabled customers to excel in the job they wanted done, which did not involve more detailed accounting reports, or getting involved with accounting details. The customer's choice was to hire someone to handle the accounting chores or buy software that helped complete the needed business tasks while avoiding entanglements in accounting complexities. And, for them, QuickBooks was a compelling means to get the job done.

Rather than a narrow mindset focused on existing products, managers would benefit from a Jobs-to-Be-Done mindset that can lead to deep insights about the jobs customers hire their products to do. A significant benefit is new knowledge about jobs to be done that orchestrates redesigned product offerings for both existing and new customers.

There are two significant advantages for decision-making that follow from using the knowledge-building loop of Figure 2.1 with attention to the evaluation of alternative hypotheses. First, one can reach a recommendation that others find compelling due to the process used and the likelihood of a successful outcome if implemented. Second, the analysis can introduce an alternative hypothesis missing from the current majority view; even though this alternative is not accepted, it leads to more open-minded inquiry with the potential to discover genuine insights leading to a significantly improved decision.29

The next chapter analyzes the interrelationships among a firm's knowledge-building proficiency, work, innovation, and resource allocation.

NOTES

- 1 Edward D. Hess, 2014, Learn or Die: Using Science to Build a Leading-Edge Learning Organization. New York: Columbia University Press, p. 75.

- 2 Ray Dalio, 2017, Principles. New York: Simon & Schuster, p. 188.

- 3 Hadley Cantril, Adelbert Ames, Jr., Albert H. Hastorf, and William H. Ittelson, 1949, “Psychology and Scientific Research,” Science 110, Nos. 2862, 2863, 2864: 461–464, 491–497, 517–522.

- 4 Hadley Cantril, ed., 1960, The Morning Notes of Adelbert Ames, Jr. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

- 5 Jakob Hohwy, 2013, The Predictive Mind. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- 6 Bartley J. Madden, 2012, “Management's Worldview: Four Critical Points about Reality, Language, and Knowledge Building to Improve Organization Performance,” Journal of Organizational Computing and Electronic Commerce 22(4): 334–346.

- 7 Even a scientist working alone on a problem still connects to the ideas of other scientists. See William Duggan, 2003, The Art of What Works: How Success Really Happens. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- 8 Michael S. Gazzaniga, 2018, The Consciousness Instinct: Unraveling the Mystery of How the Brain Makes the Mind. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

- 9 David Eagleman, 2011, Incognito: The Secret Lives of the Brain. New York: Pantheon Books.

- 10 Chris Frith, 2007, Making Up the Mind: How the Brain Creates Our Mental World. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, pp. 17 and 132.

- 11 John Dewey's later work in philosophy stressed how individuals participate in creating their realities; see Rollo Handy and E. C. Harwood, 1973, Useful Procedures of Inquiry. Great Barrington, MA: Behavioral Research Council and Franklin P. Kilpatrick, ed., 1961, Explorations in Transactional Psychology. New York: New York University Press. Ames noted that his visual demonstrations enabled people to experience his innovative concepts, which in his opinion could not be adequately communicated with words alone.

- 12 Richard L. Gregory, 2009, Seeing through Illusions. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- 13 For an insightful argument that our perceptions are shaped by natural selection to promote survival, not reveal truth, see Donald Hoffman, 2019, The Case against Reality: Why Evolution Hid the Truth from Our Eyes. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. In particular note the discussion in Chapter 3 of an exchange of letters between the author and Francis Crick.

- 14 Teppo Felin, Jan Koenderink, and Joachim I. Krueger, 2016, “Rationality, Perception, and the All-Seeing Eye,” Psychonomic Bulletin and Review published online December 7, 2016.

- 15 Lera Boroditsky, 2009, “Operational Perceptual Freedom.” In Ed. John Brockman, What Have You Changed Your Mind About? New York: Harper Perennial, pp. 342–343.

- 16 Ludwig Wittgenstein, 1922, Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus. Trans. C. K. Ogden. New York: Harcourt, Brace & Co., www.gutenberg.org/files/5740/5740-pdf.pdf.

- 17 Louis V. Gerstner, 2002, Who Says Elephants Can't Dance?: Inside IBM's Historic Turnaround. New York: Harper Business, pp. 117 and 189.

- 18 William T. Powers, 1992, Living Control Systems II: Selected Papers of William T. Powers. Gravel Switch, KY: The Control Systems Group, pp. 256–257.

- 19 See Chapter 5 in Bartley J. Madden, 2014, Reconstructing Your Worldview: The Four Core Beliefs You Need to Solve Complex Business Problems. Naperville, IL: LearningWhatWorks. Warren Mansell and Timothy Carey, 2009. “A Century of Psychology and Psychotherapy: Is an Understanding of ‘Control’ the Missing Link between Theory, Research, and Practice?” Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, and Practice 82(3): 337–353. Richard S. Marken, 2009, “You Say You Had a Revolution: Methodological Foundations of Closed-Loop Psychology,” Review of General Psychology 13(2): 137–145. If you thought the design of robots could benefit from a PCT perspective, you would be right. For example, Henry H. Yin, “Restoring Purpose in Behavior.” In Gianlucs Baldassarre and Marco Mirolli, eds., 2013, Computational and Robotic Models of the Hierarchical Organization of Behavior. New York: Springer. The International Association for Perceptual Control Theory has a comprehensive website, www.IAPCT.org.

- 20 Debra Smith, 2000, The Measurement Nightmare: How the Theory of Constraints Can Resolve Conflicting Strategies, Policies, and Measures. New York: St. Lucie Press, p. 4.

- 21 Steve Zaffron, 2012, “Breakthrough Leadership: From Ideas to Impact.” https://stevezaffron.com/breakthrough-leadership-from-ideas-to-impact/.

- 22 See Sameer B. Srivastava and Amir Goldberg, 2017, “Language as a Window into Culture,” California Management Review 60(1): 56–69. Eccles and Nohria state: “The way people talk about the world has everything to do with the way the world is ultimately understood and acted in,” Robert G. Eccles and Nitin Nohria, 1992, Beyond the Hype: Rediscovering the Essence of Management. Boston: Harvard Business School Press, p. 29.

- 23 In his famous essay, “The Methodology of Positive Economics,” Milton Friedman asserted that a model or theory should be judged solely on the accuracy of its predictions and not on the realism of its assumptions. That this can easily facilitate elegant mathematical models that are of little practical value, or worse, uncritically accepted by policy-makers is an argument I made in Bartley J. Madden, 1991, “A Transactional Approach to Economic Research,” Journal of Socio-Economics 20(1): 57–71. In personal correspondence, www.LearningWhatWorks.com/news.htm, Friedman replied, “I have no criticism of it [my argument] and it has no criticism of me.” I interpret this to mean that in his own work he has addressed the issue of practical usefulness regardless of others who use the methodology of positive economics to produce elegant mathematical models built upon unrealistic assumptions that have little practical value. For a further critique of unrealistic assumptions, see Paul Pfleiderer, 2020, “Chameleon Models: The Misuse of Theoretical Research in Financial Economics.” Economica 87(345): 81–107. Available at SSRN.com/abstract=2414731.

- 24 Christensen, Clayton M. and Michael E. Raynor. 2003., “Why Hard-nosed Executives Should Care about Management Theory,” Harvard Business Review 81(9): 67–74.

- 25 Platt, John R., “Strong Inference,” Science, October 16, 1964, 146: 347–353. In this article, Platt emphasized the design of crucial experiments capable of excluding hypotheses (clear proof that an assumption is wrong) based on experimental results. Also see Douglas S. Fudge, 2014, “Fifty Years of J. R. Platt's Strong Inference,” Journal of Experimental Biology 217: 1202–1204, in which the author writes that multiple hypotheses are needed “because of our tendency to become attached to our ideas, which can lead to science becoming an irrational argument among scientists, rather than a rational competition among ideas … [Platt's vision] is one grounded in a firm belief in a knowable reality, and one in which good explanations rise out of the ashes of those shown to be false.”

- 26 Caro, Tim, Amanda Izzo, Robert C. Reiner Jr., Hannah Walker, and Theodore Stankowich, “The Function of Zebra Stripes,” Nature Communications 5 (April 2014), article number 3535, and Caro, Tim, 2016, Zebra Stripes. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- 27 Further research showed that flies were not affected while approaching zebras, but the zebra stripes interfered with a controlled landing by the flies. Tim Caro et al., 2019, “Benefits of Zebra Stripes: Behaviour of Tabanid Flies around Zebras and Horses,” February 20 PLOS ONE.

- 28 Christensen, Clayton M., Taddy Hall, Karen Dillon, and David S. Duncan, 2016, Competing against Luck: The Story of Innovation and Customer Choice. New York: Harper Business.

- 29 Charlan Nemeth, 2018, In Defense of Troublemakers: The Power of Dissent in Life and Business. New York: Basic Books.