Chapter 15

Putting It All Together: The “Dancing with the Trend” Model

One of the basic premises for model development is the concept of Occam’s Razor. Occam’s (or Ockham’s) razor is a principle attributed to the 14th-century logician and Franciscan friar William of Ockham. This is the basic premise of all scientific and theory building. The simpler of two methods is preferable. Simplest may not be best, but is a good start.

It is the only form that takes its own advice: Keep things simple. A model built on sound principles will probably survive the tumult of the markets much longer and better than an overly complex model. Complexity has a tendency to fail, and unfortunately, usually at the worst time. I always think about the complex algorithms used by Long Term Capital in 1998, when they began to fail miserably. Their complete failure and the foolish effort to tweak them almost took the New York Fed down with them. It seems that too often investors associate complexity with viability. That is just not correct.

There are three primary components to a sound model, and just like a three-legged stool, a model must be stable in all environments. They are:

- Weight of the evidence measurement of market movement.

- Rules and guidelines to show how to trade the weight of the evidence information.

- Strict discipline to follow the process with confidence.

Remove any one of those components, and like the legs on a three-legged stool, the model will tumble. The following discusses each of these components and how they fit together to produce a comfortable rules-based trend-following model. I mention comfortable because you must be comfortable with your model or you will constantly challenge it and probably abandon it if not. The only thing that really matters when judging a strategy is actual, real-time, verifiable results. Everything else is just window dressing.

Weight of the Evidence

The “Dancing with the Trend” model described herein uses a basket of technical measures to determine the overall risk levels in the market place. The model has been constructed so that each technical measure (see Chapter 13) carries a specified weight based on extensive research. These weights (percentage points) are cumulated to derive a total model point measure to build the weight of the evidence. This approach gives one the ability to protect assets in difficult market environments (low weight of the evidence totals) while also allowing one to make tactical shifts to better performing assets when the investment environment is more favorable (high weight of the evidence totals).

Each of the weight of the evidence components is assigned a weight based on their percentage contribution to the overall model, with the total of all components equal to 100. The weight of the evidence is further broken into four different levels in this example. For example, if the sum of the weights of the indicators is equal to 65, the model would be deemed to be yellow as the yellow range is from 51 to 80. These ranges and the number of ranges are determined during model development and research. Sometimes only three ranges are necessary, and, in fact, for most it is advisable. In this example, I have four ranges, with the middle two considered as transition ranges. This allows the model to absorb some market volatility without penalizing the process.

- 0–30 = Red

- 31–50 = Orange

- 51–80 = Yellow

- 81–100 = Green

An alternative range could also be used. One must decide on how close the stops are in order to determine how many levels, and in particular the middle or transitional levels are used. Like the porridge in the three bears’ story, one is going to be just right (for your model).

- 0–30 = Red

- 31–70 = Yellow

- 71–100 = Green

These levels serve the model concept as they determine what set of rules to use to buy, sell, or trade up (trade up is the act of replacing current poor relative performing holdings with better performing holdings). Asset allocation (equity exposure) values are also a function of the weight of the evidence level. There are also three additional Initial Trend Measures (ITM), which provide guidance to the buying and trading up process using the point system. These help refine the various levels using shorter term trend measures.

The weight of the evidence model uses these primary components that, when used together, help determine the most appropriate asset allocation level as measured by the model. The terminology below of “turning on” refers to the fact that the measurement is indicating a positive or upward trend. In this example, the price-based components are:

- Trend Capturing (one component)

- Price Short

- Price Medium

- Price Long

- Adaptive Trend

The next group of components fall into the category of Market Breadth measures. Market Breadth indicators allow one to look at the market internals that are not always reflected in the price action of the market. This is much like a physical examination performed by your doctor. You might be feeling fine but when the doctor runs his diagnostic tests he is getting an internal look that can potentially find a health risk that you were not aware of. That is the precise reason it is recommended you have routine physical exams. I’ll spend some time here to illustrate how such Breadth measures can be used to evaluate potential risk in the markets that is not readily apparent in the price action alone.

To use a very simplistic example, let’s focus on the Dow Jones Industrial Average Index (DJIA), which is comprised of 30 large blue-chip issues. If IBM (or another of the high priced stocks in the index) was up 15 percent on the day, but the other 29 DJIA stocks were down slightly, the DJIA could possibly still be up for the day because of the large price contribution from IBM. The price movement of the index would be showing a positive action. However, if you look at the fact that only one of the 30 was up while 29 were down a much different picture of the overall health of the market is yielded. Since DJIA is a price-weighted index, this example demonstrates how a high priced stock can influence the average. Similarly, capitalization weighted indices (S&P 500) can have cases were the top 10 percent of the components will influence the daily return of the index. Additionally, the Nasdaq 100 index, which comprises the top capitalization stocks in the Nasdaq Composite shows that the top 10 stocks of the Nasdaq 100 account for about 43 percent of the movement of the entire Nasdaq 100 index. The largest capitalization stock in the index can be up $20 for the day and the smallest capitalization stock can be down one cent for the day, but with breadth, they evenly cancel each other out. Breadth, on the other hand, shows the true internal action of an index from treating all issues equally. Therefore, Breadth measures will generally begin to decline prior to price or cap weighted indexes at market tops. Tom McClellan is fond of saying that breadth arrives at the party on time, but always leaves early.

During periods of market distribution or the long drawn-out topping process, investors will tend to move from their more illiquid higher risk holdings (usually small cap issues) into what they perceive as less risky large capitalization blue chip stocks. This serves to drive price and capitalization indices (which most are) higher, while breadth, being equally weighted, shows that most issues are declining. As the breadth measures turn off it reduces risk by tightening your sell criteria.

Figure 15.1 is an example from 2007 in which the price-based capitalization index moved higher (top plot of S&P 500), the breadth-based advance decline measure (bottom plot) moved lower.

FIGURE 15.1 Why Breadth Is Used

Source: Chart courtesy of MetaStock.

Here are the breadth-based measures used in this example of the weight of the evidence used in the Dance with the Trend model:

- Advance/Decline

- New Highs/New Lows

- Up Volume/Down Volume

- Breadth Combination

- Trend Capturing (2 components)

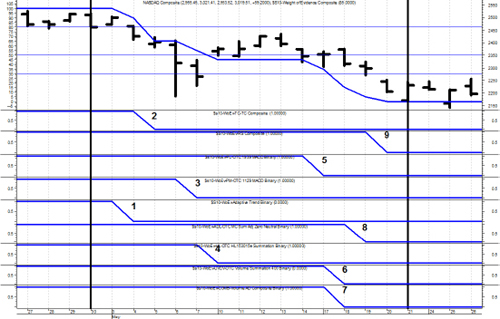

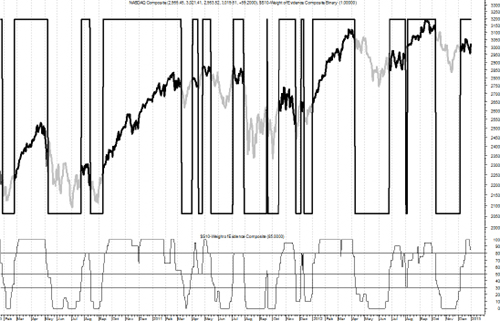

The single remaining weight of the evidence component is the relative strength measure. Recall that it is a compound measure using small cap versus large cap, growth versus value, and breadth versus price (see Figure 13.24 and Figure 13.25). Figure 15.2 shows the Nasdaq Composite in the top plot with the total weight of the evidence overlaid on it and below are all nine weight of the evidence binary indicators. You can see from the individual binaries that they turn on and off independently. As one binary comes on the total weight of the evidence in the top plot moves up based upon how many points that binary was worth.

FIGURE 15.2 Weight of the Evidence Explanation 1

Source: Chart courtesy of MetaStock.

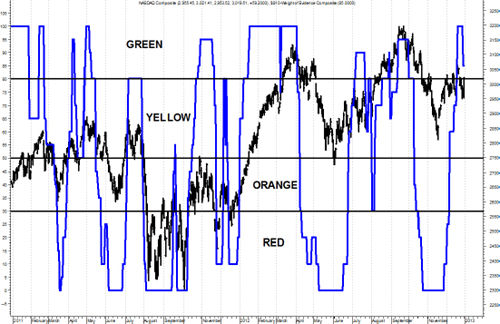

Figure 15.3 shows an example of the weight of the evidence in the top plot overlaid on the Nasdaq Composite going from 100 just after the first vertical line down to zero just before the second vertical line. The weight of the evidence component binaries are all shown below. You can see that as they turn off, the total weight of the evidence line in the top plot declines based on the percentage value of the binary that turned off. Below are the dates and names of the weight of the evidence components and when they turned off. You can see that it took from 5/4/2010 until 5/20/2010 for all of them to turn off and take the weight of the evidence from 100 to zero. However, don’t forget as the weight of the evidence transitions through the four zones the stops on each holding are tighter so a nearly defensive position was reached by 5/7/2010.

FIGURE 15.3 Weight of the Evidence Explanation 2

Source: Chart courtesy of MetaStock.

- 5/4/2010 Adaptive Trend

- 5/5/2010 Trend Capturing

- 5/7/2010 Price Medium

- 5/10/2010 High Low

- 5/17/2010 Price Long

- 5/18/2010 Up Volume Down Volume

- 5/18/2010 Breadth Combination

- 5/19/2010 Advance Decline

- 5/20/2010 Relative Strength

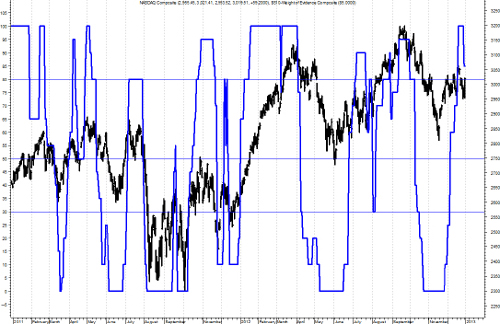

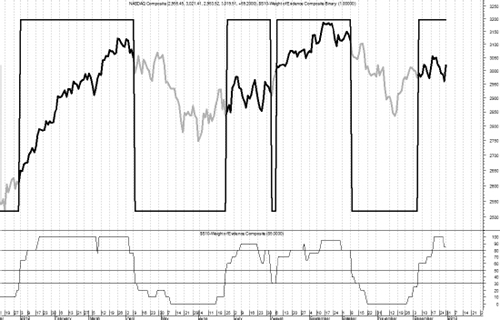

Figure 15.4 shows the total weight of the evidence with the Nasdaq Composite overlaid. When the weight of the evidence is at the top, which is 100, it means all of the components are saying the trend is up. When it is at the bottom, which is zero, it means all of the components are saying the trend is not up. The three horizontal lines are at 80, 50, and 30, which break the weight of the evidence into four sections, which are described in the next section. I think you can clearly see that when the weight of the evidence is strong (> 50), the market is generally in an uptrend.

FIGURE 15.4 Weight of the Evidence Explanation 3

Source: Chart courtesy of MetaStock.

Investing with the Weight of the Evidence

When all of the indicators are “on” you have very strong uptrends occurring, and they have been confirmed by a number of weight of the evidence indicators so there is strong confirmation of the trends in place. There is a strong relative strength relationship in that there is ample speculation taking place in the markets to help drive upward price movement and investor sentiment is good. In addition, the positive price movement is being fully supported by the internal breadth measures. This is a favorable time to be invested, and this is when you want to participate in the equity markets because of the favorable opportunity of market gains.

However, when all of the indicators are off, a negative or insufficient uptrend is in place and there is no confirmation of a solid positive trend. The relative strength relationship is showing unfavorable market sentiment, which leads to less than favorable market conditions. In addition, the breadth measures are telling you that the market internals are weak. This is a time when the risk of negative price movement is at its greatest, and the time to be invested in much safer assets such as cash or cash equivalents until market conditions improve.

Transitional markets occur when the weight of the evidence is either increasing or decreasing. If the weight of the evidence is increasing one will generally begin increasing the equity allocations as evidence builds until you get to a point where most or all of the indicators are on at which time you would have generally moved to a fully invested position. When the weight of the evidence is declining, the stops that are in place on every holding in the portfolio are tightened. These stops, which act as a downside protection mechanism in the event the market price action reverses suddenly, control the sell side discipline, and if these stops are hit the positions are sold. Stopped out positions are not replaced until you once again begin to see an improvement in the market’s performance or the weight of the evidence, depending on the rules and guidelines. Therefore, as the weight of the evidence continues to decline (indicators turning off) and holdings continue to hit stop loss levels one is naturally decreasing the equity allocation until such time that you might be fully defensive. Figure 15.5 shows the Nasdaq Composite with the weight of the evidence composite overlaid and the four levels defined previously.

FIGURE 15.5 Weight of the Evidence Levels

Source: Chart courtesy of MetaStock.

Table 15.1 shows in table form what Figure 11.5 displays visually.

TABLE 15.1 Weight of the Evidence Levels Table

The technical measures are based on sound principles, solid research, and are applied with uncompromised discipline. This approach to trend following for money management provides a level of comfort to investing in the equities market that few can question.

Ranking and Selection

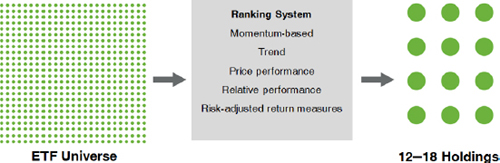

Chapter 14 presented all of the ranking measures and details on each one. Here I just bring them into the full picture of how the overall model works. From the ETF universe (currently about 1,400), using the mandatory ranking measures of Trend, Price Performance, Relative Performance, and Risk Adjusted Return Measures, a fully invested portfolio will contain anywhere from 12 to 18 holdings. Clearly this number is decided by the strategy team or the investment committee and is used here merely as an example. The Ranking Measures bring the giant universe of possible ETFs down to only the ones qualified for investment based upon their technical and risk performance. Figure 15.6 helps visualize this ranking and selection process.

FIGURE 15.6 ETF Universe Reduced by Ranking Measures

Figure 15.7 is a sample of the ranking measures that are mandatory with some of the top-rated ETFs based on the value of Trend. In this particular example you can see that many fixed income issues ranked high, plus the energy ETFs, and a few equity-based ETFs. From this I would guess the market was in a transition area going from up to down or vice versa because not many equity related ETFs are performing well.

FIGURE 15.7 Mandatory Ranking Measures

To access an online version of this figure, please visit www.wiley.com/go/morrisinvestingebook.

Figure 15.8 shows not only the mandatory ranking measures, but also the tie-breakers, all of which were covered in detail in Chapter 14. The conditional formatting allowed in spreadsheet software is invaluable for this process. If the negative numbers are displayed and easily determined it drastically speeds up and simplifies the selection process.

FIGURE 15.8 Mandatory and Tie-Breaker Ranking Measures

To access an online version of this figure, please visit www.wiley.com/go/morrisinvestingebook.

Discipline

Up to this point in the book, I have given many examples of discipline and its constant need when using an objective model. It is mentioned again here because it is a critically important component. In fact, I think discipline is the sole reason most analysts fail when using a model.

Sell Criteria

Selling of holdings is accomplished in two ways: one is when actively trading up and a holding is sold because it is being replaced by a holding that has better ranking measures, and two, when a holding hits its stop loss level.

Tweaking the Model

A model that is based on sound principles using a rational approach to measuring trends, a strong set of reasonable rules, and the discipline to follow it, (especially, when it seems it isn’t working) is the secret to a successful model process. Tweaking a model is the equivalent of creating destruction. The best models are the ones that are least sensitive to changes in their parameters.

There are times, however, when one of the measures just seems to steadily be losing its trend identification ability. I’m not saying you should never change a parameter or a model component, just don’t start tinkering with the parameters—change the component. In this case my goal is to find a replacement that only makes a positive contribution to the model’s historical performance with extremely little or no negative contribution.

Model in Action

The following charts (Figures 15.9, 15.10, 15.11, and 15.12) show the stages of the weight of the evidence model over different time periods. The binary overlaid on the Nasdaq Composite Index is a simplified process that shows an uptrend whenever the Weight of the Evidence measure is greater than 50 and a downtrend whenever it is less than 50. This method shows when the measure is essentially invested (uptrend) and when it is defensive (downtrend). The lower plot is the weight of the evidence composite.

FIGURE 15.9 Weight of the Evidence (1996–2012)

Source: Chart courtesy of MetaStock.

FIGURE 15.10 Weight of the Evidence (2007–2012)

Source: Chart courtesy of MetaStock.

FIGURE 15.11 Weight of the Evidence (2011–2012)

Source: Chart courtesy of MetaStock.

FIGURE 15.12 Weight of the Evidence (2012)

Source: Chart courtesy of MetaStock.

Remember: All of the financial theories and all of the market fundamentals will never be any better than what the trend of the market allows.

Risk Statistics, Ratios, Stops, Whipsaws, and Miscellaneous

This is a wrap-up section that contains important information and concepts, but would have been out of place if put in one of the previous chapters. Risk statistics are generally good for two purposes: predicting the probability of future outcome and comparing two funds, managers, and so on. If you have read this far, you know I only think they are good for the latter—comparison purposes. When looking at historical returns and standard deviation, you will find that they are not constant, but dependent on the time frame being analyzed. Personally, using less than five years will produce statistics that are not significant for longer-term analysis. Risk statistics come in all sizes and shapes, but comparative risk-adjusted statistics are what we discuss here. These should always be calculated using exactly the same time frames for the two series you are analyzing. Plus it is good to do this over a number of different time frames, say 5, 7, 10, 15, and even 20 years. This section also covers whipsaws, fund expenses, stop losses, and turnover.

Sharpe Ratio

The Sharpe Ratio was created by William Sharpe in the 1960s and introduced as an alternative to the reward-to-volatility ratio. Clearly, in this case, he is assuming volatility is standard deviation.

Sharpe Ratio = (Mean − Risk Free Rate) /Standard Deviation

Here is a simple example: let’s say investment A has a return of 12 percent and a Standard Deviation of 10 percent, while investment B has a return of 18 percent and a Standard Deviation of 16 percent. Let’s assume the Risk Free Rate is 3 percent. Then Investment A has a Sharpe Ratio of 0.90 ((12 − 3)/10). Investment B has a Sharpe Ratio of 0.9375 ((18 − 3)/16). Hence Investment B is a better investment based on this risk-adjusted statistic. The purpose of this example is to show that a higher standard deviation is acceptable if accompanied by a higher return.

Sortino Ratio

Created by Frank Sortino and offered as an alternative to the Sharpe Ratio, it is simply the use of downside deviation in the denominator instead of standard deviation and instead of using the Risk Free return it uses a user-defined measure of minimal acceptable return. Downside deviation sounds reasonable, but you must be careful in its determination and assess it for the data in question. If you were to determine variability in a long period of data, the downside variation would be different than if you looked at a short term part of the data.

Sortino Ratio = (Mean − Minimal Acceptable Return) / Downside Deviation

The Minimal Acceptable Return can be set as a function relative to the Mean Return using a rolling return chart.

Correlations, Alpha, Beta, and Coefficient of Determination

These were thoroughly covered in Chapters 13 and 14.

Up and Down Capture

Personally, I think this statistic on performance is the most important of all of them. It measures the cumulative return of an investment compared to a benchmark’s cumulative return in both up and down periods of the benchmark. If the value of the Up Capture is more than 100 percent, then it means that the investment captured more than 100 percent of the move when the benchmark advances. If the number is less than 100 percent, say 80 percent, then it means the investment only captured 80 percent of the up moves as the benchmark advanced. Down Capture works the same way only focusing on the downward moves of the benchmark.

For example, we have an Up Year with the Benchmark increasing 20 percent, the Up Capture of the investment is 60 percent, then the Investment made 20 percent × 60 percent = 12 percent. Assume a down year in which the benchmark declined by 40 percent, the Investment had a Down Capture of 80 percent, then the Investment returned 40 percent × 80 percent = 32 percent.

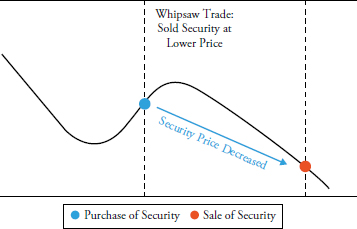

Whipsaws

Trend following has one issue that will constantly plague the investor and usually at the most least-expected time, and that is whipsaws. I have to admit, I think it just takes experience to get used to whipsaws. I hate them, but I also know that trying to adjust a model based on sound principles so that the ones in the recent past are reduced or eliminated will lead to two things: one, the performance in the past will probably be reduced, and you have probably reduced the performance going forward and probably without actually changing the overall number of whipsaws. Trying to eliminate whipsaws will often create more and at the worst time—going forward.

Up Market Whipsaw

A whipsaw can occur in both up and down markets. An up market whipsaw is when the market is trending higher, and then experiences a pullback in price such that it triggers a stop loss and a holding is sold. Shortly thereafter the market resumes its uptrend (see Figure 15.13). You follow your rules on the process of how to reinstate the equity exposure and you then purchase another asset to replace the one that was sold or you can repurchase the one that was sold as long as you are aware of wash sale rules.

FIGURE 15.13 Up Market Whipsaw

Down Market Whipsaw

A down market whipsaw occurs in a downtrend after a bottom forms, your trend measures see an uptrend developing and calls for equity exposure so you buy based on your rules. Shortly thereafter the market reverses and the downtrend resumes and the security just purchased is at its stop loss and is sold. This is the most common type of whipsaw (see Figure 15.14) because when uptrends begin the Weight of the Evidence is usually low and your trade up rules are not yet into play. When legging into a new uptrend, your goals is liquid exposure—period.

FIGURE 15.14 Down Market Whipsaw

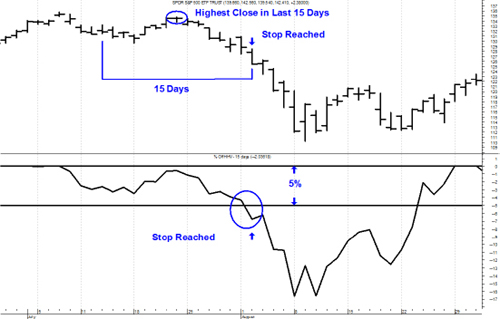

Stops and Stop Loss Protection

A stop loss is generally applied in an effort to reduce a portfolio’s exposure to the risk of downside market moves. These are determined by a number of methods, a predetermined cumulative loss is reached or on a percentage of drawdown. Stops can be justified from behavior biases such as disposition effect and loss aversion. I think it can be stated that the use of stop loss protection will almost always reduce a portfolio’s return, especially if the returns are not momentum driven. In other words, the use of stop losses in trend following is certainly better than in mean reversion strategies. Further, they provide an investor with discipline and the potential to reduce risk. Generally, though, the reality is that although many think they will improve performance, instead the real value of them is in overall risk reduction. On another note, trend following can be best served with using the reversal of trend as the stop loss technique. However, this would require some real stamina in the process as one can suffer significant losses before most trend-following methods will provide the risk reduction. Figure 15.15 shows how a moving stop loss system can work. This stop is based on a 5 percent decline in price from the highest close reached in the last 15 trading days (top oval). Therefore, that highest point reached in the past 15 days moves within the range of prices during those 15 days. In Figure 15.15 you can see the highest close was about midway back in the 15-day range, or 7 days ago to be exact. The plot at the bottom shows the percent decline from the moving 15-day highest close. Hence, once it drops below the second horizontal line at −5 percent (bottom oval) the stop is reached and the sell order is executed. Don’t waste your time creating elaborate stop loss techniques if you aren’t going to follow them. In my opinion, all stops are inviolable—period.

FIGURE 15.15 Stop Loss Example

Source: Chart courtesy of MetaStock.

This stop loss technique works well because it protects the gains from momentum investing. However, there are situations in market action that would cause this stop loss to fail, and that is during a slow nonvolatile decline. Since the stop is based on the moving past (15 days in this example), it is conceivable that the price would decline and the stop would follow it down because the decline did not exceed the stop loss percentage. Although this is rare, it is certainly possible and must be addressed. One solution is to use a stop that is measuring the trend of the holding, such as the Trend measure discussed in Chapter 14. This way, if the price was declining slowly and the percent from previous high value stop isn’t working, the trend stop will catch it before the decline in price becomes an issue.

Stop Loss Execution

This is easy! Execute it when it hits—period. Although it is easy to write this, very often managers fail to live up to this simple creed. I do not know how many times I have heard of a manager that holds a committee meeting when a stop is hit to decide whether to execute it. How truly sad! If you are going to spend time and effort in developing a stop loss process, then why would you question it when it occurs? To me, a stop loss is inviolable. Now there is an issue with stops and when they hit based on the time of day, but this can be dealt with in the rules of a good model. Here is an example of a stop loss process that considers the time of day. From rules, there is no trading during the first 30 minutes of the trading day. This has historically been referred to as amateur hour and probably not just appropriate for amateurs but professionals alike. There is often a lot of volatility just after the open as prices seek stability after watching the news and morning futures. I think it is just best to stand aside during this period. The rules also can cease all trading beyond one hour before the market closes. This period of time also has some volatility but often the time is justified for trade execution, depending on the size of the trade. In any case, the actual trading day is reduced from the market hours to help overcome the uncertainty during those periods and allow execution time.

When within the rules-based trading day (defined above), when a stop is hit, it is executed. However the execution process can also be defined with rules. For example, when a holding hits its predefined stop, an alert is sent to all involved in the trading process. This identification of a holding hitting its stop starts a 30-minute clock, which after 30 minutes, if the holding is still below its stop or goes below its stop for the remainder of the trading day, it is executed. The 30 minutes is designed to overcome the onslaught of breaking news, Internet, and constant media coverage throughout the day with the concern that occasionally the news is initially incorrect for whatever reason. Often a news story about a particular company can cause not only the company stock to decline, but the industry, the industry group, and even the sector that company is in to decline. If you were holding a technology sector ETF and Intel had a bad news blast, it could and probably would affect your technology holding. The 30-minute window from the stop being hit until it is executed allows any incorrect reporting to be corrected. Often you can see this in intra-day charts, a spike down, followed a few minutes later by a return to the previous price level. The bottom line is that you should have a process predefined on how to handle stops. It can be as simple or as complex as you feel comfortable with, but you must follow it.

Mutual Fund Expenses

If you are trying to decide on which mutual fund to buy and are looking at objectives, such as growth, conservative, or small cap, you need to know this. Most of them hug a benchmark and performance is based on how they perform relative to that benchmark. If they beat the benchmark they call it alpha, and if they don’t, they call it tracking error. Because most mutual fund managers are tied to a benchmark, expenses can become the only discernible difference among them.

You need to understand mutual fund expenses because so many times decisions on which fund to buy boils down to this factor. Expenses can cause you to forget the goal, which is to select the fund that will give you the total return you need. Below is Table 15.2, which shows three mutual funds, their total expenses, and total returns. Which mutual fund is delivering the most alpha?

TABLE 15.2 Mutual Fund Expenses

Fund C clearly delivered the most alpha. If Fund C generated the same total return as the other two with a higher expense, then Fund C manager produces the most alpha of the three funds. However, if you are a momentum buyer like me, the above does not come into play. The concern about expense ratios comes into play when often that is the only delineation among managers who all follow the same objective.

Turnover and Taxes

Turnover refers to the percentage of an investment vehicle’s holdings that have been “turned over” or replaced with other holdings in a given year. Most unconstrained tactical models generally yield a high turnover.

- The turnover is based totally on market action.

- Low volatility trends will not have high turnover.

- Short whipsaw-like moves will have high turnover.

- Rarely are there any long-term gains or losses.

- Predominately there are short-term gains and losses.

A good model will not compromise its investment process with tax considerations. Plus there is no risk of getting a long-term gain that you did not participate in. This is a phenomenon most never realize can happen until it happens and then it is too late. Most mutual funds that follow an objective will hold issues for really long periods of time, upward of many years. If you purchase shares of an open-end mutual fund, and shortly thereafter the fund manager decides to sell one of their long-term holdings, you will realize the full long-term capital gains tax, and you never participated in the actual gains.

Remember: Taxes are the consequence of successful investing.

Watching a Tactical Strategy over the Short Term

Most tactical unconstrained strategies are long term. Following them daily is insane. Following them even quarterly is misleading. Many tactical unconstrained strategies do not have a benchmark. This is critical to understand and convey. Almost the entire world of money managers is tied to benchmarking and rebalancing. Many tactical unconstrained strategies do neither. Often, because of one’s investment model, it will be out of sync with the market, which is why comparing it to a benchmark like the S&P 500 on an improper basis (short term) is frustrating. You must realize that expecting it to track the daily, weekly, or even monthly direction of a benchmark is admitting that you do not understand this process.

Benchmarking

Many funds/strategies are tied to a benchmark. In fact, I think most are tied to a benchmark. The goal of these managers is to try to beat the benchmark. Some do and some don’t; yet when the number beating or failing to beat the benchmark is usually not worthy of comment, especially over time. I like to say that benchmarking is what you try to do when you have no idea what to do. The World of Finance is wrapped up in relative performance and comparison. Relative performance is a widely used investment tool, but often causes horrible investment decisions. If a client is told his or her account is up 15 percent, they are happy; until you tell them the market was up 20 percent. This often causes a client to search for a new fund or advisor who claims to beat the market. We all know that no one can legally make that promise but carefully worded marketing material can easily give the reader a subliminal message that makes them believe it can be done.

The cycle of performance chasing is the beginning of a vicious process of moving money from what is perceived to be a better performing fund or strategy. Sadly, these moves usually happen at the point in time when they should add to their current account instead of sell it. In the case of tactical unconstrained management, which is what the Dancing with the Trend strategy is, trying to select a benchmark to measure performance is losing sight of the strategy’s goals and the client’s investment horizon. The only benchmark that should matter is the strategy return required to meet your goals. Most will find that in their later years a strategy that meanders to the upside with minimal downside action will be their most comfortable ride. Benchmarking in the investing world is common, often used in sales and marketing, rarely of any true value to an investor who is not interested in a strategy that does not attempt to beat a benchmark. It is, however, human nature to try to measure and compares things; sadly that trait can cause poor results. In brief, benchmarking leads to chasing performance that generally leads to poorer performance.

Full Cycle Analysis

If you would like an investment plan more oriented to your life span rather than your attention span, you probably would be better served with a tactical approach to the markets. The markets are not tied to the calendar, yet the world of finance is. Performance measures should be appropriate for the strategy, which means that tactical unconstrained should be measured over the full cycle of the market, whether it be top to top, or trough to trough. As an example, in Figure 15.16, a full cycle can be from A to C or from B to D.

FIGURE 15.16 Full Cycle Analysis

Source: Chart courtesy of MetaStock.

Actual Results from a Rules-Based Trend-Following Strategy—Dancing with the Trend

I am guilty of overkill with the multitude of charts and tables in the remainder of this chapter; however, I have a reason for it. First of all, the Dance with the Trend strategy does not have a benchmark. No benchmark exists for trend following that uses stops and treats cash as an asset class. Personally, I don’t think there ever will be. Secondly, many people look at a wide variety of performance data and risk statistics and it seems logical to me to provide as many different “looks” as I can. Hopefully, I included one you are familiar with and can use. This section shows you the results from the Dance with the Trend strategy, a rules-based strategy that uses a weight of the evidence approach to trend following, rules and guidelines, and strict discipline. The Dance with the Trend strategy began on December 31, 1996, with data through December 31, 2012. It has real results from a 17-year record of real money management; no back-tested results and no hypothetical results.

Dance with the Trend Performance and Risk Comparison

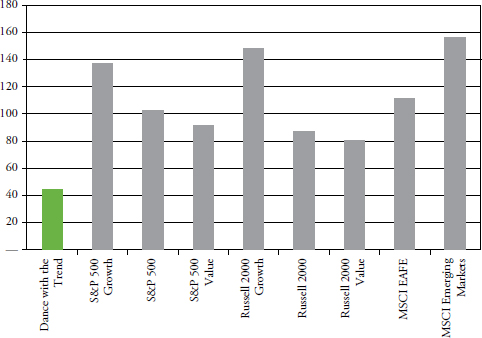

The Dance with the Trend strategy is compared to S&P 500 Growth, S&P 500, S&P 500 Value, Russell 2000 Growth, Russell 2000, Russell 2000 Value, MSCI EAFE, and MSCI Emerging Markets. These categories cover large cap, small cap, and international.

Figure 15.17 shows the number of instances of drawdowns greater than 10 percent. The Dance with the Trend strategy had only two instances. All others had at least six.

FIGURE 15.17 Drawdowns Greater than 10 Percent

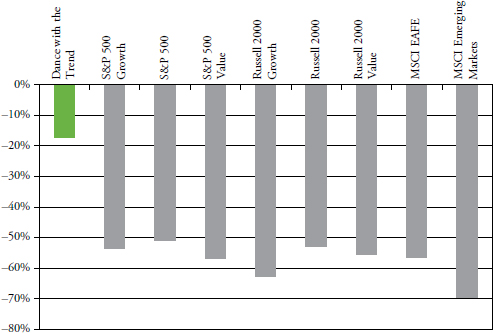

Figure 15.18 shows the number of instances of drawdowns greater than 20 percent, which is also considered a bear market. The Dance with the Trend strategy had no drawdowns greater than 20 percent. Let me say that again. The Dance with the Trend strategy had no drawdowns greater than 20 percent.

FIGURE 15.18 Drawdowns Greater than 20 Percent

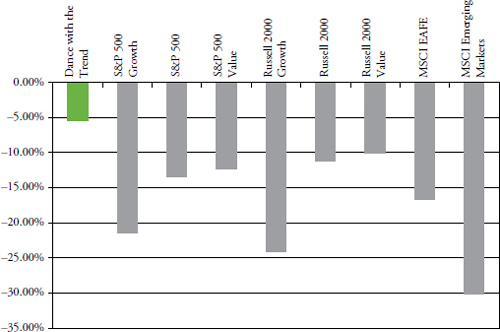

Figure 15.19 shows the total number of months spent in a drawdown of greater than 10 percent. The Dance with the Trend strategy had 42 months spent in a state of drawdown of greater than 10 percent, while others could be measured in decades.

FIGURE 15.19 Number of Months with Drawdowns Greater than 10 Percent

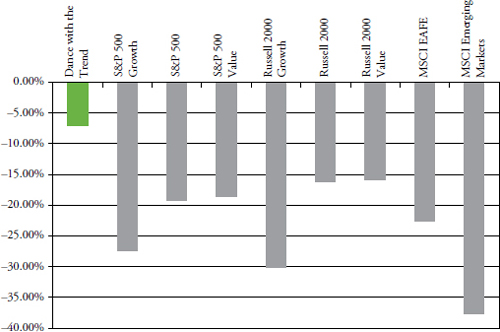

Figure 15.20 shows the number of months in Bear Market territory. The Dance with the Trend strategy had zero months in a bear status. Zero!

FIGURE 15.20 Number of Months with Drawdowns Greater than 20 Percent

Figure 15.21 shows the maximum drawdowns. The Dance with the Trend strategy had a maximum drawdown of −17 percent. Remember there were two giant bear markets during this period, each with drawdowns near −50 percent.

FIGURE 15.21 Maximum Drawdown

Figure 15.22 shows the average drawdowns. The average drawdown of the Dance with the Trend strategy was −5.1 percent.

FIGURE 15.22 Average Drawdown

Figure 15.23 shows the Ulcer Index, which is a measure of risk. The Dance with the Trend strategy had an Ulcer Index of only −7 percent.

FIGURE 15.23 Ulcer Index

Dance with the Trend over a Full Market Cycle

Any strategy that is a trend follower that treats cash as an asset class and moves to cash during bad periods in the market does not have a benchmark. The only way to correctly measure performance for a strategy such as the Dance with the Trend strategy is over the full market cycle. The next three tables include the ubiquitous 60/40 strategy for comparison along with the also ubiquitous S&P 500 Index. When one does not have a benchmark, at least something needs to be used. You can recall my comments on “The 60/40 Myth” in Chapter 3.

The following tables use many statistical and risk measures; their definitions are scattered throughout the book, but all are reproduced here for convenience.

- Return—This is the annualized return, which is also the geometric mean of the returns.

- Cumulative Return—This is the compound return of the series from the beginning date.

- Standard Deviation—A measure of the average deviation of the returns from their mean (same as sigma).

- Downside Risk—Also known as the semi-standard deviation as the sum is restricted to those returns that are less than the mean. Author note: Be careful here and be aware of the amount of data being analyzed. An inadequate amount of data would make this value unreliable.

- Beta versus Market—This is the sensitivity of the series compared to that of a benchmark. A beta of one means the return series and the benchmark are similar.

- Alpha versus Market—This is the mean of the excess returns of the series over beta times the benchmark. Author note: This is horribly overused in modern finance and very difficult to distinguish from returns derived from beta.

- Sharpe Ratio—The annualized excess returns of the series divided by the annualized standard deviation.

- Best Period Return—The maximum of the returns in the period of data analyzed.

- Worst Period Return—The minimum of the returns in the period of the data analyzed.

- Up Capture versus Market—This measures how well the series did in capturing the up periods of the benchmark.

- Down Capture versus Market—This measures how well the series did in capturing the down periods of the benchmark.

- Maximum Drawdown—The maximum compounded loss the series incurred during any period of measurement.

- R-Squared versus Market—Shows how closely related to the benchmark the series is based on the variance of returns. This is also known as the goodness of fit.

- Correlation versus Market—This measures how closely related the variance of the series is to the benchmark.

Table 15.3 shows the performance data for the first full bear/bull cycle in this century. When a risk statistic is compared to the market; that market is the S&P 500 Index.

TABLE 15.3 Peak-to-Peak (April 2000–October 2007) Analysis

To access an online version of this table, please visit www.wiley.com/go/morrisinvestingebook.

Table 15.4 shows the Dance with the Trend strategy during the bull/bear cycle.

TABLE 15.4 Trough-to-Trough (October 2002–February 2009) Analysis

To access an online version of this table, please visit www.wiley.com/go/morrisinvestingebook.

Table 15.5 shows the Dance with the Trend strategy since its conception.

TABLE 15.5 Since Inception Analysis: January 1996–December 2012 (Full History)

To access an online version of this table, please visit www.wiley.com/go/morrisinvestingebook.

Dance with the Trend with Other Asset Classes

The following tables show various risk statistics for the Dance with the Trend strategy compared to a wide variety of other asset classes. If a strategy such as the Dance with the Trend strategy does not have a benchmark, then this is a more valid method of comparing performance measures. Table 15.6 shows all of the risk statistics used in the previous tables with the addition of R-squared and Correlation.

TABLE 15.6 Risk/Return Table January 1996–December 2012: Summary Statistics

To access an online version of this table, please visit www.wiley.com/go/morrisinvestingebook.

Dance with the Trend Return Analysis

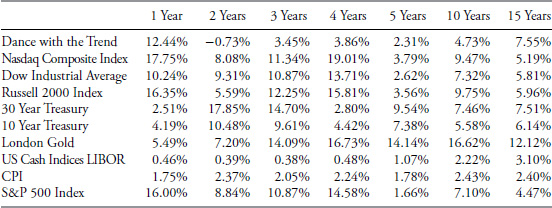

Table 15.7 shows the various asset classes’ performance over various time periods from 1 to 15 years.

TABLE 15.7 Return Analysis January 1996–December 2012 (Not Annualized If Less Than 1 Year)

Dance with the Trend Upside Downside Analysis

Table 15.8 shows statistics for various periods relative to up and down markets as determined by the S&P 500 Index.

TABLE 15.8 Upside/Downside Table January 1996–December 2012 (Single Computation)

To access an online version of this table, please visit www.wiley.com/go/morrisinvestingebook.

Dance with the Trend Comparison with Style/Asset Classes

Table 15.9 shows the performance of the Dance with the Trend strategy against a host of various asset classes.

TABLE 15.9 Asset Performance Comparison from 12/31/1995 to 12/31/2012

To access an online version of this table, please visit www.wiley.com/go/morrisinvestingebook.

Dance with the Trend Performance Comparison

Figure 15.24 shows the various asset classes from 1/1/1996 until 12/31/2012. The dotted line (Dance with the Trend) offers a fairly smooth ride. As one ages, this comfortable ride becomes more and more important. It is an investment ride that is easy to stick with over the years. Another wonderful advantage is it means that one could pull out almost all of their money at any time, independent upon market action. Think about that!

FIGURE 15.24 Asset Classes from 1/1/1996 until 12/31/2012

To access an online version of this figure, please visit www.wiley.com/go/morrisinvestingebook.

Mean Shifting

The Dance with the Trend model measures the trend of the market, then utilizes rules to scale into the trend, and maintains risk containment measures (stop loss) both absolute and relative, and when an uptrend is not identified, a cash position of up to 100 percent is utilized. There are two distribution concepts at play with this type of model. First the use of stop loss measures will reduce the downside variance and shift the return distribution mean to the right. Secondly, the baggage of trend following, known as whipsaws (see earlier in this chapter), will reduce the upside variance and shift the return distribution mean to the left. The benefit is that the mean shift to the right is much greater than the mean shift to the left, yielding a net shift to the right. (See Figure 15.25.)

FIGURE 15.25 Distribution of Returns for Dance with the Trend versus S&P 500

Table 15.10 shows monthly return distributions for the Dance with the Trend strategy from 1996 to 2012, compared to the S&P 500. You can see that the average (mean) of returns for the Dance with the Trend strategy for this 17-year period was 0.65 percent versus 0.52 percent for the S&P 500, and with lower variability as denoted by St. Dev. (standard deviation/sigma). The more significant point is the minimum (Min) value for the strategy is only −5.84 percent versus the S&P 500 at −16.94 percent.

| Dance w/Trend | S&P 500 | |

|---|---|---|

| Mean | 0.65% | 0.52% |

| Std. Dev. | 3.46% | 4.62% |

| Min | −5.84% | −16.94% |

| Max | 28.31% | 10.77% |

TABLE 15.10 Statistics from 1996–2012 Comparing Dance with the Trend to S&P 500

The top plot in Figure 15.25 is the monthly return distribution for the Dance with the Trend strategy from 1996 to 2012. The vertical axis shows the number of events that occurred at the various return levels. The shaded area is the 12-month moving average of those returns so that you can more closely relate to where the bulk of returns occurred. The second plot is the monthly return distribution of the S&P 500 over the exact same time period, also with the 12-month moving average shown. Notice the lack of negative returns (left side) on the top plot of the strategy compared to the S&P 500 in the lower plot. This ability to avoid downside returns provides a right shift (more positive) in the mean of all values. In the top plot there are two return values that have been truncated (two long lines that reach the top of the plot) in order to keep the values in the vertical axis the same as those in the lower plot. There values are 33 and 29. I think it is clear that the Dance with the Trend strategy offers higher returns in addition to much fewer returns in the negative (left) realm.

That was a lot of performance comparisons. Hopefully, you were able to grasp the message that a rules-based trend-following strategy that uses stops and treats cash as an asset class is much better than many, if not most of the investment strategies being hyped by managers who only try to follow a benchmark.