Chapter 13

Exchange Rate Regimes in the Post–Bretton Woods Era

In This Chapter

![]() Understanding floating exchange rates

Understanding floating exchange rates

![]() Evaluating interventions into floating exchange rates

Evaluating interventions into floating exchange rates

![]() Examining different types of pegged currencies

Examining different types of pegged currencies

![]() Establishing a timeline in a currency crisis

Establishing a timeline in a currency crisis

![]() Understanding the role of the IMF in the post–Bretton Woods era

Understanding the role of the IMF in the post–Bretton Woods era

This chapter is all about the exchange rate regimes observed during the post–Bretton Woods era. It uses some of the fundamental knowledge of the exchange rate regimes established in Chapter 11. In this chapter, you look at floating or flexible exchange rate regimes as well as pegged regimes which fall between the two extremes of fixed and flexible exchange rates. Because currency crises can occur under a pegged exchange rate regime, you learn both the reasons and consequences of a currency crisis. Additionally, following the end of the Bretton Woods era, the International Monetary Fund (IMF), a Bretton Woods institution, started providing funds to countries with pegged exchange rate regimes. Therefore, this chapter provides a discussion of the IMF’s activities in the post-Bretton Woods era.

Using Floating Exchange Rates

Chapter 11 notes that a fiat currency doesn’t imply a fixed exchange rate. In fact, fiat currencies are compatible with a floating exchange rate regime, in which the value of a currency is determined in foreign exchange markets.

This section focuses on two main subjects. First, I discuss the advantages and disadvantages of the floating exchange rate regime. Second, a floating exchange rate regime doesn’t necessarily lack government or central bank interventions into exchange rates; therefore, I talk about the variety of exchange rate interventions under a floating exchange rate regime.

Advantages and disadvantages of floating exchange rates

Floating exchange rates have these main advantages:

![]() No need for international management of exchange rates: Unlike fixed exchange rates based on a metallic standard, floating exchange rates don’t require an international manager such as the International Monetary Fund to look over current account imbalances. Under the floating system, if a country has large current account deficits, its currency depreciates.

No need for international management of exchange rates: Unlike fixed exchange rates based on a metallic standard, floating exchange rates don’t require an international manager such as the International Monetary Fund to look over current account imbalances. Under the floating system, if a country has large current account deficits, its currency depreciates.

![]() No need for frequent central bank intervention: Central banks frequently must intervene in foreign exchange markets under the fixed exchange rate regime to protect the gold parity, but such is not the case under the floating regime. Here there’s no parity to uphold.

No need for frequent central bank intervention: Central banks frequently must intervene in foreign exchange markets under the fixed exchange rate regime to protect the gold parity, but such is not the case under the floating regime. Here there’s no parity to uphold.

![]() No need for elaborate capital flow restrictions: Chapter 11 emphasizes the difficulty associated with trying to keep the parity intact in a fixed exchange rate regime while portfolio flows are moving in and out of the country. In a floating exchange rate regime, the macroeconomic fundamentals of countries affect the exchange rate in international markets, which, in turn, affect portfolio flows between countries. Therefore, floating exchange rate regimes enhance market efficiency.

No need for elaborate capital flow restrictions: Chapter 11 emphasizes the difficulty associated with trying to keep the parity intact in a fixed exchange rate regime while portfolio flows are moving in and out of the country. In a floating exchange rate regime, the macroeconomic fundamentals of countries affect the exchange rate in international markets, which, in turn, affect portfolio flows between countries. Therefore, floating exchange rate regimes enhance market efficiency.

![]() Greater insulation from other countries’ economic problems: Chapter 11 shows that, under a fixed exchange rate regime, countries export their macroeconomic problems to other countries. Suppose that the inflation rate in the U.S. is rising relative to that of the Euro-zone. Under a fixed exchange rate regime, this scenario leads to an increased U.S. demand for European goods, which then increases the Euro-zone’s price level. Under a floating exchange rate system, however, countries are more insulated from other countries’ macroeconomic problems. A rising U.S. inflation instead depreciates the dollar, curbing the U.S. demand for European goods.

Greater insulation from other countries’ economic problems: Chapter 11 shows that, under a fixed exchange rate regime, countries export their macroeconomic problems to other countries. Suppose that the inflation rate in the U.S. is rising relative to that of the Euro-zone. Under a fixed exchange rate regime, this scenario leads to an increased U.S. demand for European goods, which then increases the Euro-zone’s price level. Under a floating exchange rate system, however, countries are more insulated from other countries’ macroeconomic problems. A rising U.S. inflation instead depreciates the dollar, curbing the U.S. demand for European goods.

Floating exchange rates also have disadvantages:

![]() Higher volatility: Floating exchange rates are highly volatile. Additionally, macroeconomic fundamentals can’t explain especially short-run volatility in floating exchange rates.

Higher volatility: Floating exchange rates are highly volatile. Additionally, macroeconomic fundamentals can’t explain especially short-run volatility in floating exchange rates.

![]() Use of scarce resources to predict exchange rates: Higher volatility in exchange rates increases the exchange rate risk that financial market participants face. Therefore, they allocate substantial resources to predict the changes in the exchange rate, in an effort to manage their exposure to exchange rate risk.

Use of scarce resources to predict exchange rates: Higher volatility in exchange rates increases the exchange rate risk that financial market participants face. Therefore, they allocate substantial resources to predict the changes in the exchange rate, in an effort to manage their exposure to exchange rate risk.

![]() Tendency to worsen existing problems: Floating exchange rates may aggravate existing problems in the economy. If the country is already experiencing economic problems such as higher inflation or unemployment, floating exchange rates may make the situation worse. For example, if the country suffers from higher inflation, depreciation of its currency may drive the inflation rate higher because of increased demand for its goods; however, the country’s current account may also worsen because of more expensive imports.

Tendency to worsen existing problems: Floating exchange rates may aggravate existing problems in the economy. If the country is already experiencing economic problems such as higher inflation or unemployment, floating exchange rates may make the situation worse. For example, if the country suffers from higher inflation, depreciation of its currency may drive the inflation rate higher because of increased demand for its goods; however, the country’s current account may also worsen because of more expensive imports.

Intervention into floating exchange rates

A completely floating currency exists only in textbooks. Terms like dirty float or managed float refer to exchange rate regimes in which exchange rates are largely determined in foreign exchange markets, but certain interventions into exchange rates take place.

Interventions are divided into two categories:

![]() Indirect interventions: Chapters 6 and 7 show that monetary policy and the growth performance of countries affect exchange rates. Therefore, a change in monetary policy is considered an indirect intervention. Additionally, trade barriers are a form of indirect intervention into exchange rates. Chapter 5 shows that if a country imposes a tariff on imports from another country, the import-imposing country’s currency appreciates, everything else constant.

Indirect interventions: Chapters 6 and 7 show that monetary policy and the growth performance of countries affect exchange rates. Therefore, a change in monetary policy is considered an indirect intervention. Additionally, trade barriers are a form of indirect intervention into exchange rates. Chapter 5 shows that if a country imposes a tariff on imports from another country, the import-imposing country’s currency appreciates, everything else constant.

![]() Direct interventions: These interventions imply that the central bank of a country uses its domestic currency or foreign currency reserves and engages in exchanging one currency for another. The aim may be to increase the country’s competitiveness by avoiding further appreciation of the domestic currency. For example, on September 10, 2011, the Economist reported that the Swiss National Bank (SNB) was concerned about the Swiss franc’s steady appreciation against the euro. Starting in early 2010, when the exchange rate was almost CHF1.5 per euro, the Swiss franc continued to appreciate toward CHF 1 per euro. Then the SNB stepped in and announced its determination to keep the exchange rate at CHF1.20 per euro. You can understand the SNB’s concern about strengthening the Swiss franc when you realize that the export sector of this country is vital for the economy.

Direct interventions: These interventions imply that the central bank of a country uses its domestic currency or foreign currency reserves and engages in exchanging one currency for another. The aim may be to increase the country’s competitiveness by avoiding further appreciation of the domestic currency. For example, on September 10, 2011, the Economist reported that the Swiss National Bank (SNB) was concerned about the Swiss franc’s steady appreciation against the euro. Starting in early 2010, when the exchange rate was almost CHF1.5 per euro, the Swiss franc continued to appreciate toward CHF 1 per euro. Then the SNB stepped in and announced its determination to keep the exchange rate at CHF1.20 per euro. You can understand the SNB’s concern about strengthening the Swiss franc when you realize that the export sector of this country is vital for the economy.

Direct interventions can be conducted in two ways: unsterilized and sterilized. In economics, the term sterilization is used as a countermeasure, where the countermeasure may be implemented through the changes in domestic money supply.

An unsterilized intervention implies that a central bank intervenes in the foreign exchange market by buying or selling its own currency without adjusting the domestic money supply. Continuing with the previous example of Switzerland, to prevent the Swiss franc from further appreciating, the SNB can engage in direct intervention by selling domestic currency in foreign exchange markets (Swiss francs), in exchange for foreign currency, such as the dollar or the euro. This particular intervention is called an unsterilized direct intervention if the SNB doesn’t alter Switzerland’s money supply. However, if the SNB wants to alter Switzerland’s money supply following its direct intervention into foreign exchange markets, it’s called a sterilized direct intervention.

The next example continues to be about Switzerland and provides a background analysis. It provides graphs for the previous definitions of unsterilized and sterilized direct interventions and explains how sterilization affects the domestic money market.

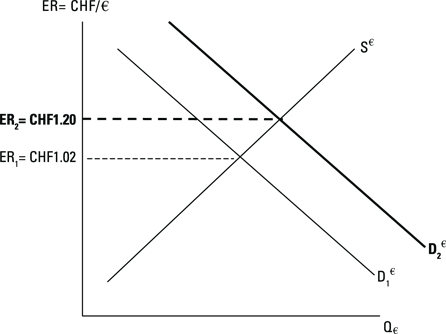

Figure 13-1 shows the market for euros. The price of the euro is measured as the number of Swiss francs necessary to buy one euro or the Swiss franc–euro exchange rate. The reason for using the euro market and the Swiss franc–euro exchange rate is that the previously mentioned Economist article reports on the Swiss franc–euro exchange rate.

Suppose that the equilibrium exchange rate of CHF 1.02 in Figure 13-1 indicates the exchange rate in late summer 2011, which made the SNB worry about Switzerland’s exports. If the SNB wants to achieve its goal of bringing the Swiss currency to the level of CHF 1.20, it needs to sell Swiss francs in exchange for euros. Because the curves in Figure 13-1 indicate the demand for and supply of euros, the actions of the SNB are shown here as an increase demand for the euro. The SNB buys euros with Swiss francs, which essentially depreciates the Swiss franc from CHF 1.02 to CHF1.20 per euro.

So far, this example implies an unsterilized intervention, which means that the SNB intervened in the foreign exchange market without taking an independent action to change the country’s money supply. Why does Switzerland’s money supply matter? The SNB pays for euros with Swiss francs, which means an increase in the number of Swiss francs in foreign exchange markets. As the Swiss franc depreciates as a result of this action, these Swiss francs in the foreign exchange market likely will return to Switzerland as payments for Swiss exports, which may be inflationary.

Figure 13-1: The Swiss National Bank sells Swiss francs.

If the SNB is concerned about an eventual increase in inflation, it can sterilize its actions in the foreign exchange market by doing the exact opposite in the domestic money market. Because the SNB increased the amount of Swiss francs in foreign exchange markets, it can decrease the country’s money supply by selling Swiss government’s bonds (also bills and notes) to financial markets in the same amount as the direct intervention.

The question is how successful direct interventions in foreign exchange markets can be. Consider the size of the foreign exchange market: It’s estimated to be up to 15 times larger than the bond market and about 50 times larger than the equity market. As of 2010, the average daily turnover was estimated to be about $4 trillion. Just compare this number to the nominal gross domestic product (GDP) of the U.S. in 2010, which was close to $15 trillion.

Therefore, direct interventions are likely to be overwhelmed by market forces. Because of the size of the foreign exchange market, a coordinated effort by a consortium of central banks may be more effective. Whether carried out by one central bank or a group of central banks, the argument for direct intervention in the foreign exchange market is that even interventions of short duration may be able to reduce the volatility in floating exchange rates.

Unilaterally Pegged Exchange Rates

Unilateral currency pegs appeared following the end of the Bretton Woods era. The difference between the pegged exchange rate regimes of pre- and post-1973 periods stems from the different types of money in these periods. As indicated in Chapter 12, the Bretton Woods system implied a variation of the metallic standard called the reserve currency standard. While the dollar as the reserve currency was pegged to gold, other currencies were pegged to the dollar, which implies a fixed exchange rate system. This kind of a system requires a multilateral agreement so that a country doesn’t change the exchange rate unilaterally. If it does, the international monetary system may be weaken or broken, which would necessitate redefining the pegs.

In the post Bretton Woods era, however, unilateral pegs started to appear. In this case, a country pegs the value of its currency to a foreign currency or a basket of foreign currencies. In the early decades following the Bretton Woods era, especially developing countries were afraid of letting their currency float. Many were engaged in expansionary monetary policies that would have depreciated their currency at a faster rate if these currencies were floating. Therefore, many developing countries recognized that currency pegs can act as a nominal anchor and signal stability when economic and political stability is in short supply. Additionally, they thought that a pegged exchange rate, pegged in a certain way, can serve these countries’ agenda regarding economic development.

There are different types of pegs among the unilateral currency pegs of the post Bretton Woods era. The most important difference between different types of pegs lies in their ability to restrict monetary policy in a country. As you will see in the discussion below, pegs can be divided between hard and soft pegs. Pegs that make it almost impossible for a country to have an autonomous or independent monetary policy are called hard pegs. Soft pegs indicate that monetary policy actions are taken at times and the peg is adjusted from time to time. Soft pegs are also called crawling pegs.

The central bank guarantees convertibility of domestic currency into the foreign currency to which it is pegged. Therefore, keeping reserves of foreign currencies or international reserves, especially of the foreign currency to which the domestic currency is pegged, becomes important.

Using hard pegs

Dollarization and currency boards are among the examples of hard pegs, which severely limit the possibility of an autonomous (independent) monetary policy in a country. Therefore, sometimes the exchange rate that stems from a hard peg is referred to as a fixed exchange rate, as in the case of a metallic standard.

In the case of dollarization, a country adopts a foreign currency to be circulated in its economy as the medium of exchange. A currency board backs the money supply or domestic currency liabilities with foreign currency or foreign currency–denominated assets to support the pegged rate. The following sections further examine these examples of hard pegs.

Dollarization

Dollarization is a general term that describes a country’s act of giving up its domestic currency and adopting another country’s currency to be used in all transactions. Despite the name, the replacing foreign currency doesn’t have to be the dollar.

Consider some historical examples for dollarization. One of the smallest European countries, Monaco, adopted the French franc in the 19th century and currently uses the euro, after France adopted the euro in 1999. Also, the U.S. dollar is the legal tender in Panama since the early 20th century.

Clearly, eliminating a country’s own money and, therefore, monetary policy is a radical step. After the domestic currency in circulation is replaced by a foreign currency, the country cannot have an autonomous monetary and exchange rate policy. Suppose that a country adopts the dollar. Because this country doesn’t have its own money and its own central bank, it has to accept the monetary policy of the U.S., conducted by the Federal Reserve Bank (the Fed). Clearly, the monetary policy–making division of the Fed, the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC), conducts its monetary policy in consideration of the economic outcomes in the U.S.; the dollarized country’s economic situation doesn’t matter to the Fed.

Therefore, the dollarized country loses its ability to address its domestic economic problems. In all countries, central banks have similar responsibilities: issuing currency, protecting the purchasing power of the currency or promoting price stability, implementing monetary policy to address business cycles (contractions and expansions), and regulating financial markets. The central bank of a dollarized country is able to regulate the country’s financial markets and promote price stability by adopting a lower-inflation country’s currency.

The dollarized country’s central bank loses something else as well. In addition to the aforementioned responsibilities, all central banks act as a lender of last resort. In times of crisis, especially financial crisis, central banks inject liquidity into financial markets. In the most recent financial crisis, the Fed acted as a lender of last resort and provided liquidity to financial markets through loans and purchasing especially mortgage-backed securities from financial markets. The European Central Bank (ECB) did the same in early 2010 by buying Greek government bonds. In these examples, both the Fed and the ECB transferred toxic assets from the balance sheets of banks and other financial firms to their own balance sheets and provided financial markets with additional liquidity. Risk premium of these financial assets (mortgage-backed securities and Greek government bonds) increased so much that, if not for the Fed or the ECB, nobody would have bought them. This situation is how central banks fulfill their function as the lender of last resort. Dollarization, however, completely eliminates the possibility that the dollarized country’s central bank can act as the lender of last resort.

You may ask what would inspire a country to dollarize. Usually countries dollarize because domestic institutions fail to keep inflation low. Following a severe banking crisis in 1999, Ecuador gave up its domestic currency, sucres, and replaced it with U.S. dollars in 2000. Ecuador was one of those countries that made too much use of the central bank’s ability to derive revenues from printing its currency, which is seignorage. Inevitably, the central bank’s ability and willingness to print money led to higher inflation rates. In the late 1990s, Ecuador’s annual inflation rate reached 96 percent. After dollarization, Ecuador’s inflation rate substantially decreased. The average inflation rate between 2003 and 2011 was about 4.4 percent. With lower inflation rates, interest rates declined as well. Whereas the average deposit rate was about 29 percent during the predollarization period, it was about 4.5 percent between 2003 and 2011.

Currency board

Currency board is another example of a hard peg. Unlike dollarization, a currency board doesn’t imply replacing the domestic currency with a foreign currency. Even though the country keeps its domestic currency in circulation, a currency board necessitates that the central bank conduct monetary policy with one objective in mind: to maintain the exchange rate with the foreign currency to which the domestic currency is pegged. What would impose discipline on the currency board’s monetary policy decisions is the fact that foreign currency reserves back domestic currency.

As in the case of dollarization, a disadvantage of having a currency board is that the central bank cannot implement monetary policy to address the country’s current economic problems. Additionally, the central bank loses its ability to act as the lender of last resort and may be able to provide temporary liquidity to the financial system during a financial crisis.

Also similar to dollarization, the main advantage of a currency board is its ability to control the inflation rate and promote price stability. Trying to keep the exchange rate at a certain level leads to discipline in monetary policies and prevents the central bank from conducting discretionary policies. Of course, if the central bank of a country can increase its reserves of the benchmark currency, it can increase the country’s monetary base.

Hong Kong is one of the most successful examples of a currency board. The Hong Kong Monetary Authority (HKMA) has maintained a fixed exchange rate of HKD7.8 to one U.S. dollar.

A not-so-successful example of a currency board arose in Argentina. Argentina introduced a currency board and pegged the peso to the U.S. dollar. However, the Argentinean currency board collapsed in 2001. Following that currency crisis, the central bank let the peso float. The appreciation in the U.S. dollar in the late 1990s was one reason for the collapse of the Argentine currency board. As the dollar appreciated, so did the peso. Considering the relevance of exports for the Argentine economy, the appreciation in the peso made the country’s exports more expensive, hurting its export performance. Still, the Argentine fiscal practices may have been more damaging to the currency board. Not only the central government, but also state governments (which have considerable autonomy in their budgets) substantially increased their spending based on loans from large U.S. banks. The central bank couldn’t monetize the debt because of the currency board and both the central and state governments kept increasing their spending. However, at one point, the lenders became wary about the size of government spending in Argentina and weren’t willing to extent more credit. The result was a severe financial and banking crisis in Argentina in 2001, which ended the currency board.

Trying soft pegs

The previous sections show that hard pegs tie the hands of the central banks. Soft pegs, on the other hand, aren’t as restrictive. There are some reasons for a country to consider a soft peg: (1) The country wants to manage its exchange rate, to promote its policy of economic development. In such a case, the country can overvalue or undervalue the domestic currency to aid its development strategy. (2) The country wants to attract incoming portfolio flows. This section discusses soft pegs that relate to development objectives. The next section deals with the kind of soft pegs that aim to attract foreign investors.

If a soft peg is used to promote a certain development policy, it’s done to either overvalue or undervalue the domestic currency. The objective itself has changed from overvaluing to undervaluing during the last decades.

I start here with overvaluing a country’s currency. Until the early 1980s, the objective of most developing countries was to industrialize, whether or not these countries had a comparative advantage in industrialization. This policy was called import substitution because the objective was to produce previously imported goods domestically. But these countries faced formidable barriers to industrialization. They had limited resources, and industrialization was expensive. They also couldn’t produce the entire final good (say, cars) domestically and were dependent on the imports of intermediate goods, energy, and so on. The import substitution strategy worked based on overvaluing domestic currencies.

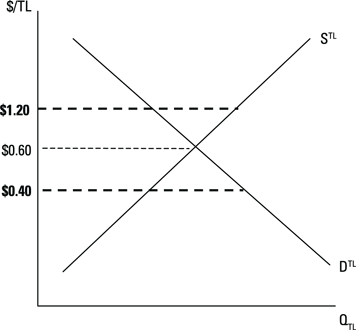

Figure 13-2: Soft peg — overvalua-tion and undervalua-tion of the Turkish lira.

In fact, countries such as Turkey maintained a variety of official exchange rates, depending on the goods they were importing. In terms of imports, overvaluation was exercised at a higher degree for goods that are strategically important for the country’s industrialization efforts.

Starting in the early 1980s, the approach to economic development changed globally from import substitution to export promotion. An undervalued currency makes the foreign price of the domestic good cheaper, which promotes the country’s export potential.

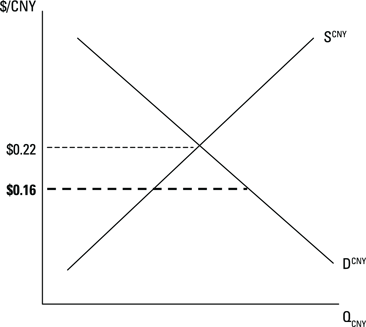

Figure 13-3: Soft peg — under-valuation of the yuan.

As in other developing countries, China followed the import substitution development strategy until the early 1980s. As Chapter 2 discusses, the dollar–yuan exchange rate was $0.58 in 1981. After changing to the export promotion strategy, the exchange rate went down to $0.12 in 1994, which was below the undervalued exchange rate of November 12, 2012, in Figure 13-3. Mainly due to criticism from developed countries, China implemented smaller revaluations in the early 2000s. This is called a crawling peg, when a country gradually devalues or revalues its currency.

The undervalued Chinese yuan, together with a lower labor cost, gave China stellar export performance, which led to large accumulations of foreign currencies (especially the dollar) by the Chinese central bank. Foreign exchange reserves of the central bank were $2 trillion in 2010.

If the objective of a soft peg is to create an advantage for a country in international trade, countries need to implement serious capital controls. In this case, if the currency isn’t freely traded and the central bank of the country unilaterally determines the exchange rate, the country should control not only international capital flows, but also its citizens’ access to foreign exchange. All developing countries that have implemented soft pegs for trade reasons have seen a lively black market arise for foreign currencies.

Attracting foreign investors with soft pegs

Unlike the examples in the previous section, the kind of soft pegs discussed in this section are implemented for other reasons than international trade. The aim here isn’t to make exports or imports less expensive. Some soft pegs are introduced to attract foreign investors to the country. In this case, the idea isn’t to attract long-term foreign direct investment (FDI), but to attract foreign portfolio investment in the country.

Portfolio investment implies investing in financial papers such as debt securities or equities. Especially developing or emerging countries are interested in attracting incoming foreign portfolio investment. These countries are in need of accumulating hard currency to finance their infrastructure investment. Among the usual sources of hard currency are export earnings and international borrowing. However, exports earnings are used to pay for imports. As to international lending, commercial bank lending to developing countries has significantly declined since the debt crisis of 1982. Therefore, some developing countries liberalized capital movements into and out of the country (capital account convertibility) in an attempt to attract foreign portfolio investment.

Although intentions were good, allowing foreign capital inflows into a developing country turned out to be risky business. During the 1990s and early 2000s, a number of currency crises arose because of the soft pegs implemented to attract foreign portfolio investment.

Currency crises may take place in different countries, but their anatomy and timeline are very similar. Following are the steps toward a currency crisis:

![]() Attempt to attract foreign portfolio investment: The government is in need of external financing and wants to make the country attractive for foreign portfolio investment.

Attempt to attract foreign portfolio investment: The government is in need of external financing and wants to make the country attractive for foreign portfolio investment.

![]() Identify the reasons for foreign investors’ reservations: The government realizes that the country will not attract portfolio investment because of the exchange rate risk. Even though this country’s (nominal) returns may be higher, investors are aware of the risk that this country’s currency will depreciate over and above the returns and the risk that they will lose money.

Identify the reasons for foreign investors’ reservations: The government realizes that the country will not attract portfolio investment because of the exchange rate risk. Even though this country’s (nominal) returns may be higher, investors are aware of the risk that this country’s currency will depreciate over and above the returns and the risk that they will lose money.

![]() Understand that the government is fiscally undisciplined and influences the central bank: One of the reasons investors expect depreciation of this currency in the future is that the government hasn’t shown any monetary and fiscal discipline in the past. Investors are concerned that the country will continue its path of expansionary macroeconomic policies. They also know that the central bank of the country isn’t independent from the fiscal authority and surrenders to the wishes of the government.

Understand that the government is fiscally undisciplined and influences the central bank: One of the reasons investors expect depreciation of this currency in the future is that the government hasn’t shown any monetary and fiscal discipline in the past. Investors are concerned that the country will continue its path of expansionary macroeconomic policies. They also know that the central bank of the country isn’t independent from the fiscal authority and surrenders to the wishes of the government.

![]() Peg the domestic currency to a hard currency: The government realizes the possibility of changing investors’ expectations without changing the country’s institutions. Why not peg the domestic currency to a hard currency such as the dollar? Suppose that this country’s currency is the krank (KR). The government announces that the pegged exchange rate is KR2 per dollar. In this case, the country uses the peg as a nominal anchor to signal stability.

Peg the domestic currency to a hard currency: The government realizes the possibility of changing investors’ expectations without changing the country’s institutions. Why not peg the domestic currency to a hard currency such as the dollar? Suppose that this country’s currency is the krank (KR). The government announces that the pegged exchange rate is KR2 per dollar. In this case, the country uses the peg as a nominal anchor to signal stability.

![]() Eliminate exchange rate risk: Announcing the pegged rate isn’t enough. The government needs to make the exchange rate risk disappear for foreign investors. Therefore, the government announces that if foreign investors invest in krank-denominated assets, then when they feel like it, they can convert their kranks into dollars at the pegged rate and leave the country. Now foreign investors have virtually no exchange rate risk and can enjoy the higher returns on krank-denominated assets.

Eliminate exchange rate risk: Announcing the pegged rate isn’t enough. The government needs to make the exchange rate risk disappear for foreign investors. Therefore, the government announces that if foreign investors invest in krank-denominated assets, then when they feel like it, they can convert their kranks into dollars at the pegged rate and leave the country. Now foreign investors have virtually no exchange rate risk and can enjoy the higher returns on krank-denominated assets.

![]() Watch to see if the peg will break: While the peg is credible, foreign investors have the best of both worlds: no exchange rate risk and higher returns on krank-denominated assets. But they are watching the country. Specifically, they are watching the country to figure out whether the current peg is credible. Note that they won’t wait until something happens to cash in their krank-denominated portfolio and get out of this country. If the peg is broken, the krank will depreciate so much that foreign investors will incur large losses, despite higher returns in this country. Therefore, foreign investors observe the country to understand whether conditions exist that will break the peg.

Watch to see if the peg will break: While the peg is credible, foreign investors have the best of both worlds: no exchange rate risk and higher returns on krank-denominated assets. But they are watching the country. Specifically, they are watching the country to figure out whether the current peg is credible. Note that they won’t wait until something happens to cash in their krank-denominated portfolio and get out of this country. If the peg is broken, the krank will depreciate so much that foreign investors will incur large losses, despite higher returns in this country. Therefore, foreign investors observe the country to understand whether conditions exist that will break the peg.

![]() Causes for the peg to break: Over the years, views on what would break the peg have changed.

Causes for the peg to break: Over the years, views on what would break the peg have changed.

• When the portfolio inflows to emerging markets were increasing starting in the late 1980s, investors were watching the fiscal and monetary policies of these countries. A credible peg indicates no expected changes in fiscal or monetary policy that will break the peg. Suppose that, while pegging the krank, the government increases its spending without raising taxes, which pressures the monetary authority to decrease its key interest rate; this situation is called monetizing the deficit. In this case, both monetary and fiscal authorities follow expansionary policies. Investors understand that the peg (KR2 per dollar) will not remain credible for long. They then expect that the peg will be broken and that the krank will substantially depreciate. When foreign investors see this, they cash in their krank-denominated assets and get dollars or other hard currencies in return. Many of the currency crises of the 1980s and early 1990s had inconsistency between the peg and the countries’ macroeconomic policies as the root cause. These kinds of crises are called first-generation currency crises.

• Some of the currency crises of the late 1990s, such as the Asian crisis of 1997–1998, belong to the group of second-generation currency crises. One after another, Thailand, Indonesia, and South Korea entered a currency crisis between August and November 1997. It wasn’t obvious that these countries were engaged in expansionary fiscal and monetary policies. The second-generation currency crises implied that foreign investors learned about emerging markets and started looking at obvious but also not-so-obvious circumstances that would break the peg. One common characteristic of the previously mentioned Asian economies was a weak financial structure that wasn’t equipped to distribute the incoming portfolio investment efficiently. For example, banks’ assets in these countries were viewed as inflated because of real estate bubbles in these countries. Investors thought that if anything went wrong in the financial systems of these countries, governments would provide large bailouts, which would break the peg. Therefore, the questionable strength of the financial system played a role in the second-generation currency crises.

![]() Pay out with hard currency: When investors sell their portfolios for hard currency, the central bank must do what it promised foreign investors when the country introduced the peg: The central bank must exchange the domestic currency for hard currency at the pegged exchange rate. Because foreign investors are now leaving the country, soon the central bank will run out of its foreign currency reserves. This event, with foreign investors cashing in their portfolios and depleting the foreign currency reserves of the central bank, is called a speculative attack on the currency.

Pay out with hard currency: When investors sell their portfolios for hard currency, the central bank must do what it promised foreign investors when the country introduced the peg: The central bank must exchange the domestic currency for hard currency at the pegged exchange rate. Because foreign investors are now leaving the country, soon the central bank will run out of its foreign currency reserves. This event, with foreign investors cashing in their portfolios and depleting the foreign currency reserves of the central bank, is called a speculative attack on the currency.

![]() Allow currency to float: Now the peg is broken. The government lets the domestic currency float, which generally leads to a large depreciation. Additionally, because the country is out of foreign currency reserves, it must restore its short-run liquidity. The country goes to the IMF and receives a loan.

Allow currency to float: Now the peg is broken. The government lets the domestic currency float, which generally leads to a large depreciation. Additionally, because the country is out of foreign currency reserves, it must restore its short-run liquidity. The country goes to the IMF and receives a loan.

Often currency crises are called by the name of the country, such as the Mexican, Argentine, or Indonesian crises. But the previous discussion about the anatomy and timeline in a currency crisis implies that although currency crises occur in different countries, why and how they happen is very similar.

Dealing with Currency Crises and the IMF

The previous section on soft pegs mentions the role of the IMF in currency crises. The timeline in a currency crisis indicates that when a country’s currency is attacked and its central bank starts losing its foreign currency reserves, the country is likely to receive financial support from the IMF. In fact, in the post–Bretton Woods era, the IMF started providing financial support to developing countries with pegged exchange rates and balance of payments problems. The IMF’s involvement in developing countries, especially between the 1970s and the late 1990s, made the institution almost a permanent fixture in many developing countries’ affairs. Therefore, this section focuses on the IMF and has two objectives: to explain the role of the IMF in the post–Bretton Woods era and to examine the role of the IMF in currency crises of the post–Bretton Woods era.

Decoding the IMF’s role in the post–Bretton Woods era

The IMF was originally a Bretton Woods organization (see Chapter 12). At the Bretton Woods Conference of 1944, it was clear that the post–World War II international monetary system was going to depend on a multilateral arrangement. The earlier periods of metallic standard didn’t have the multilateral nature of the Bretton Woods era, which was thought to have led to unilateral changes in exchange rates, undermining the fixed exchange rate regime. Additionally, the international monetary system chosen for the post–World War II period was a variation of the gold standard — namely, the reserve currency standard. This system envisioned establishing the gold parity with the reserve currency, the dollar, and pegging all other currencies to the dollar.

The role of the IMF

The Bretton Woods Conference created the IMF as a multilateral organization to oversee the pressures of current account imbalances in countries whose currencies were pegged to the dollar. As discussed in Chapter 12, the IMF tried to uphold the Bretton Woods system by providing funds to current account-deficit countries. However, as early as the late 1940s, the IMF didn’t have enough funds to manage the Bretton Woods system.

Despite this fact, the IMF wasn’t abolished with the Bretton Woods system in 1971. Developed countries were adopting flexible exchange rates, and developing countries were unwilling to let their currency float. Given their mostly expansionary fiscal and monetary policies and political uncertainty, these countries expected large depreciations in their currency if they let them float. Developing countries wanted to have a nominal anchor — something stable in their sometimes highly unstable economies. Additionally, as mentioned previously, these countries wanted to manage their exchange rates to support their development strategy of import substitution. The IMF had another important reason to stick around, too. As the Bretton Woods system ended, the first oil price increase of 1973 hit all countries, especially developing countries. The IMF fit naturally in the role of the provider of additional liquidity to developing countries. Consequently, as developed countries were adopting flexible exchange rates, the age of unilateral pegs started for developing countries.

The IMF and unilateral pegs

With many developing countries deciding on unilaterally pegged exchange rates, the IMF was on familiar ground. Although using unilateral pegs is different than pegging currencies to the dollar under the reserve currency system, currency pegs need outside financing (albeit for different reasons). In the Bretton Woods system, persistent and large current account deficits initiated a loan from the IMF. In the post–Bretton Woods era, unilateral pegs periodically led to reserve depletion in countries, which necessitated a loan from the IMF.

In a unilateral peg, the country pegs its currency to a hard currency such as the dollar. For the peg to be credible, the country cannot make extensive use of monetary policy, especially expansionary monetary policy involving increases in the money supply. In many developing countries, this scenario was (and, to some extent, still is) difficult to accomplish. Most of their central banks aren’t independent from the fiscal authority, and the fiscal authority can exercise strong control over the monetary authority. Therefore, whenever the fiscal authority wants to increase its spending without increasing taxes, monetary policy is the easiest way to get these funds. Of course, an expansionary monetary policy leads to higher inflation and, at times, hyperinflation, which reduces the credibility of the peg. As previously discussed in this chapter, when the peg loses its credibility, investors expect that the peg will be broken and the currency will depreciate. To avoid future losses, holders of the domestic currency exchange the domestic currency at the pegged rate for the hard currency, such as the dollar, which leads to the depletion of the central bank’s reserves. At this point, the country can’t make payments on its debt or for its imports. Then it’s time to go to the IMF and get a loan.

Unlike the IMF’s financial assistance during the Bretton Woods era, IMF loans during the post–Bretton Woods era are associated with conditionality. The reason for attaching conditionality to the IMF support during the post–Bretton Woods era is that a unilateral peg loses its credibility for only one reason: The country was following incompatible fiscal and monetary policies under the peg. In other words, rapidly increasing public-sector spending pressures monetary policy to be expansionary, creating expectations that the peg will be broken and the currency will depreciate.

In 2009, the IMF introduced a major overhaul in its programs and conditionality. Since then, the IMF also provides financial support to countries that are experiencing a financial crisis that didn’t stem from pegged exchange rates. Consider the example of Greece, a member of the European Union and the Euro-zone. In 2010, the IMF approved a €30 billion three-year loan for Greece to help the country get out of its debt crisis. This example is one of the largest financial supports the IMF has provided to any country. Because Greece is in the Euro-zone, there is no pegged exchange rate situation here. (This is more a problem of implementing independent and expansionary fiscal policies as a member of a common currency area.) As discussed in Chapter 14, the recent cases involving Greece, Italy, Spain, Ireland, and others in the Euro-zone don’t imply exogenous crises. These countries’ financial problems didn’t come out of nowhere. The Euro-zone countries in crisis have varying degrees of expansionary fiscal policies, uncoordinated public finance schemes, and proneness to banking crises.

In a way, the IMF has remained the same since its inception: an institution that provides financial support to countries with home-brewed economic problems.

Providing stability or creating moral hazard?

Because the IMF support to countries without pegged exchange rates is still new, not much evidence indicates what this kind of support achieves. However, the IMF’s support to developing countries and the effects of its support have been widely examined. The most important effect of the IMF’s support is the provision of much-needed liquidity to a country following a currency crisis. Private international lenders would be unwilling to step in and provide funds to a country in crisis. With the help of the IMF, the crisis country with depleted foreign currency reserves can pay for its imports and make payments on its debt. Additionally, evidence indicates that IMF support decreases the spread on a country’s sovereign bonds and other debt instruments, which implies a decline in the default risk of a country.

Countries receiving financial support have widely criticized the IMF’s conditionality. In terms of its traditional lending to developing countries with pegged exchange rates, the IMF’s conditionality prescribes a reduction in public spending (reducing subsidies, freezing civil servants’ wages, and so on) and discipline in monetary policy. Even the conditionality associated with the IMF’s recent lending to European countries such as Greece has been criticized for being too intrusive. Three facts can help put this view of intrusive IMF conditionality in perspective:

![]() First, the IMF sometimes provides very large funds to troubled countries, so large that crisis countries can’t get these amounts from any other lender.

First, the IMF sometimes provides very large funds to troubled countries, so large that crisis countries can’t get these amounts from any other lender.

![]() Second, interest rates associated with these funds are much lower than the market rate, meaning that they are much lower than the interest rate that a commercial bank would charge.

Second, interest rates associated with these funds are much lower than the market rate, meaning that they are much lower than the interest rate that a commercial bank would charge.

![]() Third, most of the time, the problems forcing a country to go to the IMF are home-brewed or preventable problems.

Third, most of the time, the problems forcing a country to go to the IMF are home-brewed or preventable problems.

Therefore, when putting these three facts together, conditionality serves as the shadow price of IMF programs because their nominal price (the interest rate on IMF loans) is so low.

Even though the IMF’s conditionality made sense, the institution introduced a new approach to its programs and conditionality in 2009, possibly because it grew tired of criticism. In its own words, the IMF modernized its conditionality to reduce the stigma associated with its lending. Here’s what it did:

![]() First, the IMF wants conditions attached to IMF loans to reflect program countries’ strength in policies and fundamentals. This point reflects a change from ex-post to ex-ante conditionality. Before 2009, the IMF considered the crisis situation of a country and formulated its conditionality after the fact (ex-post). Now, especially when providing the short-term liquidity facility (SLF) to countries currently in a temporary crisis but otherwise with strong fundamentals, the Fund doesn’t engage in ex-post monitoring of these countries.

First, the IMF wants conditions attached to IMF loans to reflect program countries’ strength in policies and fundamentals. This point reflects a change from ex-post to ex-ante conditionality. Before 2009, the IMF considered the crisis situation of a country and formulated its conditionality after the fact (ex-post). Now, especially when providing the short-term liquidity facility (SLF) to countries currently in a temporary crisis but otherwise with strong fundamentals, the Fund doesn’t engage in ex-post monitoring of these countries.

![]() Second, the IMF wants stronger ownership of IMF programs by program countries. Program countries’ government should be able to defend the conditions attached to IMF loans to their constituents and work diligently to fulfill them.

Second, the IMF wants stronger ownership of IMF programs by program countries. Program countries’ government should be able to defend the conditions attached to IMF loans to their constituents and work diligently to fulfill them.

![]() Third, the IMF wants to be mindful of the effects of its conditions on the most vulnerable segments of the population in program countries.

Third, the IMF wants to be mindful of the effects of its conditions on the most vulnerable segments of the population in program countries.

Additionally, the IMF increased member countries’ access to quotas. As discussed in Chapter 12, the Bretton Woods system provided the IMF with its own funds through a quota system. It worked just like a membership subscription. The same setup continued after the end of the Bretton Woods era. Of course, now the IMF has 188 member countries, and each member country is assigned a quota based on the country’s relative size in the world economy. In addition to the member country’s voting power, quota affects its access to the IMF’s financial support. The overhaul in 2009 doubled the access limits to 200 percent of quota on an annual basis and to a 600 percent of quota cumulative limit. Exceptions include Greece, where the IMF’s support amounted to more than 3,200 percent of this country’s quota.

Reducing the nominal vigor of conditionality and substantially increasing member countries’ access to financial support may increase the criticism of the IMF, which focuses on moral hazard. The term moral hazard means creating an environment in which people or countries can make wrong decisions without paying the price for these decisions (or paying a much smaller price than they otherwise would).

One of the signs of moral hazard associated with IMF programs is the recidivism observed in these programs. In this context, recidivism means the recurrence of the economic problem that requires the country to seek the IMF’s assistance. In the post–Bretton Woods era, most developing countries with pegged exchange rates have received multiple IMF programs. This fact has been interpreted as a sign of the ineffective nature of the IMF programs. The view implies that, despite conditionality, IMF programs cannot prevent future domestic macroeconomic policies that lead to a reserve loss. It means that the total cost of IMF support (conditionality plus interest rate) may not be higher than the benefit of what countries think they are receiving by implementing policies that are incompatible with their peg. Now that, since 2009, the IMF has enlarged its support to developed countries without a peg but with a financial crisis, it can create a different kind of recidivism.

The counterfactual argument is used against the criticism of the IMF. In this context, the counterfactual indicates the outcome in the absence of the IMF’s support. The IMF and its supporters maintain that the economic outcome would have been much worse without the IMF’s support. It means that, despite possible moral hazard, funds provided by the IMF prevent currency or financial crises from getting larger and more harmful. However, measuring the counterfactual and proving that the IMF’s support actually averts a much larger crisis is difficult, if not impossible.

Additionally, whether it’s a problem with pegged exchange rates in a developing country or a financial crisis in a developed country, the policy combinations leading to these crises are well known. If these policy combinations are avoided, to a large extent, receiving financial support from the IMF can be avoided as well.

Mirror, Mirror: Deciding Which International Monetary System Is Better

Until now, this chapter and the previous two chapters have examined various types of exchange rate regimes. Professional and laymen alike have an opinion about what kind of an international monetary system the world should have. Therefore, this section compares alternative international monetary systems by highlighting their advantages and disadvantages.

Nostalgic about the Bretton Woods system? The case for fixed exchange rates

A metallic standard system such as the gold standard or the reserve currency standard has the following advantages:

![]() Price stability: This advantage has been viewed as one of the virtues of the metallic standard. Price stability implies that changes in prices are small, gradual, and expected. One of the most important factors that can affect price stability is monetary policy. As discussed in Chapters 11 and 12, conducting monetary policy under a metallic standard isn’t possible. Most of the time, the concern is that the central bank inflates the economy through expansionary monetary policies or, in extreme cases, by printing money. In a metallic standard, no such fear exists because, if a country implements especially expansionary monetary policies, the metallic standard is no longer viable and must be abandoned. Therefore, price stability is embedded in the metallic standard. This system avoids hyperinflation as well. In contrast, a central bank can print fiat currency at a high rate and generate hyperinflation. There are examples of high inflation rates where central banks had to introduce incredibly large banknotes. For example, in 1923, Germany introduced a banknote for 20 billion German marks, which could buy 20 pounds of bread, 20 glasses of beer, or a little more than half a pound of meat. Similarly, in 1993, Yugoslavia introduced a banknote for 500 billion dinars.

Price stability: This advantage has been viewed as one of the virtues of the metallic standard. Price stability implies that changes in prices are small, gradual, and expected. One of the most important factors that can affect price stability is monetary policy. As discussed in Chapters 11 and 12, conducting monetary policy under a metallic standard isn’t possible. Most of the time, the concern is that the central bank inflates the economy through expansionary monetary policies or, in extreme cases, by printing money. In a metallic standard, no such fear exists because, if a country implements especially expansionary monetary policies, the metallic standard is no longer viable and must be abandoned. Therefore, price stability is embedded in the metallic standard. This system avoids hyperinflation as well. In contrast, a central bank can print fiat currency at a high rate and generate hyperinflation. There are examples of high inflation rates where central banks had to introduce incredibly large banknotes. For example, in 1923, Germany introduced a banknote for 20 billion German marks, which could buy 20 pounds of bread, 20 glasses of beer, or a little more than half a pound of meat. Similarly, in 1993, Yugoslavia introduced a banknote for 500 billion dinars.

![]() Economic stability and prosperity: A metallic standard can diminish the short-run fluctuations in a country’s output, which are also called business cycles. The reason for decreasing volatility in output may lie in price stability. Price stability, or the absence of large and unexpected changes in the average price level, may work as a signal to producers for how much to produce. Therefore, when price stability exists, fewer busts and booms and more economic prosperity may result.

Economic stability and prosperity: A metallic standard can diminish the short-run fluctuations in a country’s output, which are also called business cycles. The reason for decreasing volatility in output may lie in price stability. Price stability, or the absence of large and unexpected changes in the average price level, may work as a signal to producers for how much to produce. Therefore, when price stability exists, fewer busts and booms and more economic prosperity may result.

![]() Fixed exchange rates: A metallic standard leads to fixed exchange rates (see Chapters 11 and 12). In a gold standard, each country determines the gold parity of its currency, which fixes the exchange rates between countries. In a reserve currency system, the reserve currency has a gold parity, and all other currencies are pegged to the reserve currency, which also leads to fixed exchange rates. Fixed exchange rates enable the following:

Fixed exchange rates: A metallic standard leads to fixed exchange rates (see Chapters 11 and 12). In a gold standard, each country determines the gold parity of its currency, which fixes the exchange rates between countries. In a reserve currency system, the reserve currency has a gold parity, and all other currencies are pegged to the reserve currency, which also leads to fixed exchange rates. Fixed exchange rates enable the following:

• The reduction of uncertainty in international trade and portfolio flows: Exchange rate risk is a barrier to international business. Under the fixed exchange rate regime, nobody has to use scarce resources to guess the next period’s exchange rate.

• An automatic balance of payment adjustment mechanism to maintain internal and external balance: This mechanism, also called the price–specie–flow mechanism, takes care of imbalances between countries’ current account and price levels. If a country runs a current account surplus and accumulates specie, prices increase, making this country’s goods more expensive to foreigners. This situation reduces the current account surplus in the home country and the current account deficit in the foreign country. In the case of a current account deficit, the country is losing specie. Prices decline, making this country’s goods less expensive to foreigners and reducing the current account deficit.

• A symmetrical adjustment of monetary policies under a gold standard: If the home country’s central bank increases the money supply, it puts downward pressure on the home country’s interest rates. This situation makes other countries’ assets more attractive to investors. Because central banks are obligated to trade their currencies for gold at fixed rates, investors sell the home country’s currency, buy gold, and sell gold to other central banks so that they can get other currencies to make use of countries’ higher interest rates. The home country lost gold reserves, and the other countries now have larger gold reserves. Because gold reserves are part of the money supply, the money supply is declining in the home country and increasing in other countries. This situation increases interest rates in the home country and decreases them in foreign countries.

However, fixed exchange rates have disadvantages as well. Before presenting these disadvantages, we can question some of the advantages of fixed exchange rates:

![]() Questionable price stability: A metallic standard is considered to promote price stability. However, some studies indicate that the gold standard era experienced large fluctuations in the average price level. These fluctuations appear to have been caused by the changes in the relative price of gold with respect to the price of goods and services. For example, suppose that the gold parity indicates $35 for an ounce of gold, and the price of a typical basket is twice as much ($70). This situation implies a price level of $70 per output basket. If a major gold discovery occurs, the price of the output basket would increase, say, to $85. At the same time, the relative price of gold in terms of output would decline. It was 0.5 ($35 ÷ $70) before the discovery of new gold; it would be 0.41 ($35 ÷ $85) now. If no change takes place in the gold parity of $35 for an ounce of gold, the price level increases from $70 to $85, creating an inflation rate of 21 percent.

Questionable price stability: A metallic standard is considered to promote price stability. However, some studies indicate that the gold standard era experienced large fluctuations in the average price level. These fluctuations appear to have been caused by the changes in the relative price of gold with respect to the price of goods and services. For example, suppose that the gold parity indicates $35 for an ounce of gold, and the price of a typical basket is twice as much ($70). This situation implies a price level of $70 per output basket. If a major gold discovery occurs, the price of the output basket would increase, say, to $85. At the same time, the relative price of gold in terms of output would decline. It was 0.5 ($35 ÷ $70) before the discovery of new gold; it would be 0.41 ($35 ÷ $85) now. If no change takes place in the gold parity of $35 for an ounce of gold, the price level increases from $70 to $85, creating an inflation rate of 21 percent.

![]() Questionable economic stability and prosperity: As mentioned previously, because price stability leads to economic stability and, therefore, prosperity, the usual assumption is that the metallic standard years are associated with higher growth and lower volatility in growth. One of the disastrous economic slowdowns in recent history, the Great Depression, happened under the gold standard. Additionally, as discussed in Chapter 11, competitively contractionary monetary policies were implemented during the gold standard starting in the 18th century, which led to lower output growth and higher unemployment.

Questionable economic stability and prosperity: As mentioned previously, because price stability leads to economic stability and, therefore, prosperity, the usual assumption is that the metallic standard years are associated with higher growth and lower volatility in growth. One of the disastrous economic slowdowns in recent history, the Great Depression, happened under the gold standard. Additionally, as discussed in Chapter 11, competitively contractionary monetary policies were implemented during the gold standard starting in the 18th century, which led to lower output growth and higher unemployment.

![]() Questionable price–specie–flow mechanism: The price–specie–flow mechanism didn’t work as well in theory under a gold standard. But it really doesn’t work in a reserve currency standard. If the price–specie–flow mechanism had functioned, all countries’ current accounts would be balanced. However, as discussed in Chapter 12, during the Bretton Woods era, some countries had persistent current account surpluses, and others had current account deficits. Theoretically, surplus countries were to lend to deficit countries. This scheme doesn’t work when countries with persistently large current account deficits also have problems repaying their loans.

Questionable price–specie–flow mechanism: The price–specie–flow mechanism didn’t work as well in theory under a gold standard. But it really doesn’t work in a reserve currency standard. If the price–specie–flow mechanism had functioned, all countries’ current accounts would be balanced. However, as discussed in Chapter 12, during the Bretton Woods era, some countries had persistent current account surpluses, and others had current account deficits. Theoretically, surplus countries were to lend to deficit countries. This scheme doesn’t work when countries with persistently large current account deficits also have problems repaying their loans.

Additional disadvantages of the metallic standard follow:

![]() Imports of other countries’ unemployment and inflation rates: Because countries can’t implement autonomous monetary policies under a metallic standard, they many import their trade partner’s inflation and unemployment rates. For example, if the inflation rate is increasing in a country, at the given exchange rate, its consumers may increase their demand for foreign goods, thus increasing the prices in other countries. Similarly, if a country experiences lower output growth and higher unemployment, at the given exchange rate, it buys less from other countries, which may have an adverse effect on other countries’ output and employment.

Imports of other countries’ unemployment and inflation rates: Because countries can’t implement autonomous monetary policies under a metallic standard, they many import their trade partner’s inflation and unemployment rates. For example, if the inflation rate is increasing in a country, at the given exchange rate, its consumers may increase their demand for foreign goods, thus increasing the prices in other countries. Similarly, if a country experiences lower output growth and higher unemployment, at the given exchange rate, it buys less from other countries, which may have an adverse effect on other countries’ output and employment.

![]() Increase in precious metal reserves: Under a metallic standard, such as the gold standard, central banks need to hold an adequate amount of gold reserves to maintain their currency’s gold parity and have some additional gold to intervene in their exchange rates. However, central banks cannot increase their gold reserves as their economies grow. One possibility for increasing gold reserves is discovering new gold mines. If gold production isn’t increasing, central banks compete for gold. They sell their domestic assets to buy gold, decreasing their money supply and possibly adversely affecting output and employment.

Increase in precious metal reserves: Under a metallic standard, such as the gold standard, central banks need to hold an adequate amount of gold reserves to maintain their currency’s gold parity and have some additional gold to intervene in their exchange rates. However, central banks cannot increase their gold reserves as their economies grow. One possibility for increasing gold reserves is discovering new gold mines. If gold production isn’t increasing, central banks compete for gold. They sell their domestic assets to buy gold, decreasing their money supply and possibly adversely affecting output and employment.

![]() Potential influence of precious metal producers: Whatever precious metal is in the metallic standard, producers of this metal may have an influence on the macroeconomic conditions in countries with the metallic standard. In terms of gold production, South Africa, China, and the Russian Federation occupy first, third, and seventh places. In terms of gold reserves, South Africa, the Russian Federation, and Australia take the first three places.

Potential influence of precious metal producers: Whatever precious metal is in the metallic standard, producers of this metal may have an influence on the macroeconomic conditions in countries with the metallic standard. In terms of gold production, South Africa, China, and the Russian Federation occupy first, third, and seventh places. In terms of gold reserves, South Africa, the Russian Federation, and Australia take the first three places.

Don’t like fixed things? The case for flexible exchange rates

As mentioned in Chapters 11 and 12, during wars and other military conflicts, the gold standard was abandoned. During these times, fiat currency and, consequently, flexible exchange rates ruled. Therefore, the post–Bretton Woods era starting in 1973 with its fiat currency and flexible exchange rates is no stranger to the international monetary system. The only difference is that, although the fiat currency/flexible exchange rate combination was implemented as a transition policy during wars under a metallic standard, this combination became the norm after 1973.

A perception problem crops up with the gold standard. Because the gold standard is associated with fixed exchange rates and renders monetary policy ineffective, the gold standard means stability. However, as indicated in Chapters 11 and 12, history has seen no continuous gold standard period. The impossibility of conducting independent monetary policy under a metallic standard prompted countries to go off the standard during wars, independence wars, revolutions, and similar events.

The flexible exchange rate system has these advantages:

![]() Flexible exchange rates as automatic stabilizers: The necessity of maintaining internal and external balance under a metallic standard is based on the fact that a metallic standard leads to a fixed exchange rate regime. If the relative price of currencies is fixed and a country’s output, employment, and current account performance and other relevant economic variables change, the exchange rate cannot change. This fact causes friction in the entire economic system. However, if exchange rates are allowed to change, they change in the appropriate direction, given the nature of changes in the variables affecting the exchange rates. As mentioned in Chapters 5–7, the monetary policy and growth performance of a country affect exchange rates. For example, when foreigners’ demand for a country’s exports declines, output also decline and the country’s currency depreciates. This situation helps improve the country’s export performance because depreciation makes the country’s goods cheaper to foreigners. If the same initial shock happened under the fixed exchange rate regime (decline in the demand for the country’s exports), then because the exchange rate can’t change, the country must reduce the money supply, which further decreases the output.

Flexible exchange rates as automatic stabilizers: The necessity of maintaining internal and external balance under a metallic standard is based on the fact that a metallic standard leads to a fixed exchange rate regime. If the relative price of currencies is fixed and a country’s output, employment, and current account performance and other relevant economic variables change, the exchange rate cannot change. This fact causes friction in the entire economic system. However, if exchange rates are allowed to change, they change in the appropriate direction, given the nature of changes in the variables affecting the exchange rates. As mentioned in Chapters 5–7, the monetary policy and growth performance of a country affect exchange rates. For example, when foreigners’ demand for a country’s exports declines, output also decline and the country’s currency depreciates. This situation helps improve the country’s export performance because depreciation makes the country’s goods cheaper to foreigners. If the same initial shock happened under the fixed exchange rate regime (decline in the demand for the country’s exports), then because the exchange rate can’t change, the country must reduce the money supply, which further decreases the output.

![]() Monetary policy autonomy: Under the flexible exchange rate regime, countries can implement autonomous monetary policies to address problems with inflation and output. Because monetary policies affect inflation rates, countries can decide on their long-run inflation rate and don’t have to import their trade partners’ inflation rate, as is the case under a fixed exchange rate. A larger divergence among inflation rates has occurred during the post–Bretton Woods era. Clearly, the extent of monetary policy in either direction (expansionary or contractionary) affects the exchange rate under the flexible exchange rate system. An increase (decrease) in the money supply leads to the depreciation (appreciation) of a currency.

Monetary policy autonomy: Under the flexible exchange rate regime, countries can implement autonomous monetary policies to address problems with inflation and output. Because monetary policies affect inflation rates, countries can decide on their long-run inflation rate and don’t have to import their trade partners’ inflation rate, as is the case under a fixed exchange rate. A larger divergence among inflation rates has occurred during the post–Bretton Woods era. Clearly, the extent of monetary policy in either direction (expansionary or contractionary) affects the exchange rate under the flexible exchange rate system. An increase (decrease) in the money supply leads to the depreciation (appreciation) of a currency.

The main disadvantages of the flexible exchange rate system follow:

![]() Exchange rate risk: The main disadvantage of flexible exchange rates is their volatility. In the post–Bretton Woods era, one of the characteristics of flexible exchange rate is their excess volatility. The changes in exchange rates are more frequent and larger than the underlying fundamentals imply.

Exchange rate risk: The main disadvantage of flexible exchange rates is their volatility. In the post–Bretton Woods era, one of the characteristics of flexible exchange rate is their excess volatility. The changes in exchange rates are more frequent and larger than the underlying fundamentals imply.

![]() Potential for too much use of expansionary monetary policy: The downside of being able to conduct autonomous monetary policies is the ability to create higher inflation rates. Under a flexible exchange rate regime, expansionary or contractionary monetary policies can address recessionary or inflationary pressures, respectively. Especially when expansionary monetary policies are frequently used, higher rates of inflation follow.

Potential for too much use of expansionary monetary policy: The downside of being able to conduct autonomous monetary policies is the ability to create higher inflation rates. Under a flexible exchange rate regime, expansionary or contractionary monetary policies can address recessionary or inflationary pressures, respectively. Especially when expansionary monetary policies are frequently used, higher rates of inflation follow.

![]() Questionable stabilizing effects: Previously, automatic stabilizing was mentioned as an advantage of the flexible exchange rate system. Exchange rates change in the appropriate direction when the country’s inflation rate, output, and current account balance change. Especially in terms of current account imbalances, exchange rates determined in the foreign exchange markets are supposed to change to prevent the occurrence of persistent and large current account deficits and surpluses. However, some countries have deficits (such as the U.S., Spain, Portugal, and Greece), and some countries have a surplus (such as Germany and China). Moreover, the data indicate long swings in major exchange rates, which are called misalignments. Therefore, it seems that flexible exchange rates do not change frequently enough to eliminate current account imbalances. An adverse effect of these misalignments is that they give deficit countries the motivation to impose trade restrictions.

Questionable stabilizing effects: Previously, automatic stabilizing was mentioned as an advantage of the flexible exchange rate system. Exchange rates change in the appropriate direction when the country’s inflation rate, output, and current account balance change. Especially in terms of current account imbalances, exchange rates determined in the foreign exchange markets are supposed to change to prevent the occurrence of persistent and large current account deficits and surpluses. However, some countries have deficits (such as the U.S., Spain, Portugal, and Greece), and some countries have a surplus (such as Germany and China). Moreover, the data indicate long swings in major exchange rates, which are called misalignments. Therefore, it seems that flexible exchange rates do not change frequently enough to eliminate current account imbalances. An adverse effect of these misalignments is that they give deficit countries the motivation to impose trade restrictions.

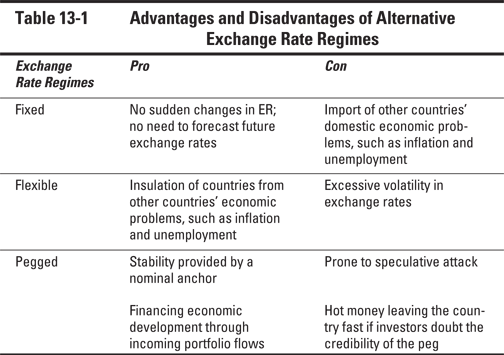

Intermediate regimes and overview of alternative exchange rate regimes