Chapter 5

Animating a Bouncing Ball

The best way to learn how to animate is to jump right in and start animating. By doing so, you’ll take a good look at the 3ds Max® animation tools so you can start editing animation and developing your timing skills.

Topics in this chapter include the following:

- Animating the ball

- Refining the animation

A classic exercise for all animators is to create a bouncing ball. It is a straightforward exercise, but there is much you can do with a bouncing ball to show character. Animating a bouncing ball is a good exercise in physics as well as cartoon movement. You’ll first create a rubber ball, and then you’ll add cartoonish movement to accentuate some principles of the animation. Aspiring animators can use this exercise for years and always find something new to learn about bouncing a ball.

In preparation, download the Bouncing Ball project from the companion web page at www.sybex.com/go/3dsmax2013essentials to your hard drive. Set your current project by choosing Application ⇒ Manage ⇒ Set Project Folder and selecting the Bouncing Ball project that you downloaded.

Animating the Ball

Your first step is to keyframe the positions of the ball. As you learned in Chapter 1, “The 3ds Max Interface,” keyframing is the process—borrowed from traditional animation—of setting positions and values at particular frames of the animation. The computer interpolates between these keyframes to fill in the other frames to complete a smooth animation.

Open the Animation_Ball_00.max scene file from the Scenes folder of the Bouncing Ball project you downloaded. If you receive a warning to Disable Gamma/LUT, click OK.

Start with the gross animation, or the overall movements. This is also called blocking. First, move the ball up and down to begin its choreography.

Follow these steps to animate the ball:

Figure 5-1: The Time slider allows you to change your position in time and scrub your animation.

Figure 5-2: The Auto Key button records your animations.

This exercise has created two keyframes, one at frame 0 for the original position the ball was in, and one at frame 10 for the new position to which you just moved the ball.

Copying Keyframes

Now you want to move the ball up to the same position in the air as it was at frame 0. Instead of trying to estimate where that was, you can just copy the keyframe at frame 0 to frame 20.

You can see the keyframes you created in the timeline; they appear as red boxes. Red keys represent Position keyframes, green keys represent Rotation, and blue keys represent Scale. When a keyframe in the timeline is selected, it turns white. Now let’s copy a keyframe:

Figure 5-3: Press Shift and move the keyframe to copy it to frame 20.

Once you copy keyframes if for any reason you want to change their parameters, you can access keyframe values in the timeline. Just right-click directly on the keyframe and a popup menu will appear. Choose from the menu what track you want to modify; you will get a type-in dialog to edit keyframe value.

Using the Track View–Curve Editor

Right now the ball is going down and then back up. To continue the animation for the length of the timeline, you could continue to copy and paste keyframes as you did earlier—but that would be very time-consuming, and you still need to do your other homework and clean your room. A better way is to loop, or cycle, through the keyframes you already have. An animation cycle is a segment of animation that is repeatable in a loop. The end state of the animation matches up to the beginning state, so there is no hiccup at the loop point.

In 3ds Max terminology, cycling animation is known as parameter curve out-of-range types. This is a fancy way to create loops and cycles with your animations and specify how your object will behave outside the range of the keys you have created. This will bring us to the Track View, which is an animator’s best friend. You will learn the underlying concepts of the Curve Editor as well as its basic interface throughout this exercise.

The Track View is a function of two animation editors, the Curve Editor and the Dope Sheet. The Curve Editor allows you to work with animation depicted as curves on a graph that sets the value of a parameter against time. The Dope Sheet displays keyframes over time on a horizontal graph, without any curves. This graphical display simplifies the process of adjusting animation timing because you can see all the keys at once in a spreadsheet-like format. The Dope Sheet is similar to traditional animation exposure sheets, or X-sheets.

You will use the Track View – Curve Editor (or just the Curve Editor for short) to loop your animation in the following steps:

Figure 5-4: The Curve Editor shows the animation curves of the ball.

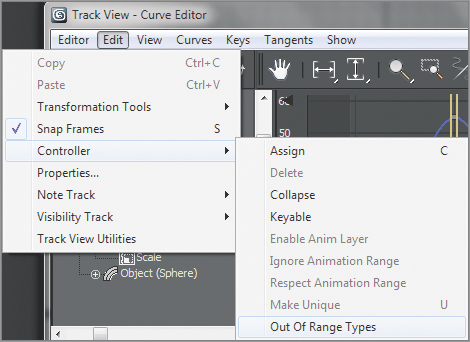

Figure 5-5: Selecting Out-of-Range Types

Figure 5-6: Choosing to loop your animation

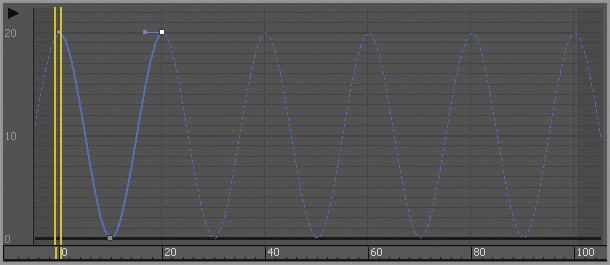

Figure 5-7: The Curve Editor now shows the looped animation curve.

Reading Animation Curves

As you can see, the Track View – Curve Editor (from here on called just the Curve Editor) gives you control over the animation in a graph setting. The Curve Editor’s graph is a representation of an object’s parameter, such as position (values shown vertically) over time (time shown horizontally). Curves allow you to visualize the interpolation of the motion. Once you are used to reading animation curves, you can judge an object’s direction, speed, acceleration, and timing at a mere glance.

Here is a quick primer on how to read a curve in the Curve Editor.

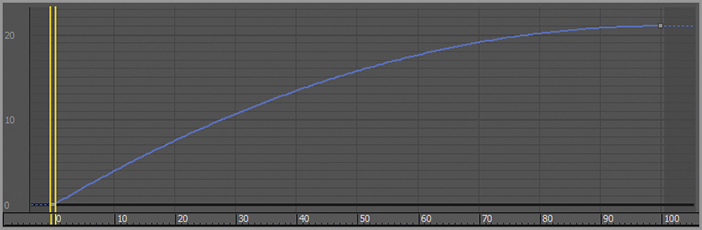

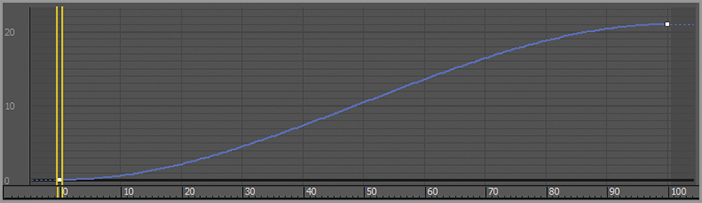

In Figure 5-8, an object’s Z Position parameter is being animated. At the beginning, the curve quickly begins to move positively (that is, to the right) on the Z-axis. The object shoots up and comes to an ease-in, where it decelerates to a stop, reaching its top height. The ease-in stop is signified by the curving beginning to flatten out at around frame 70.

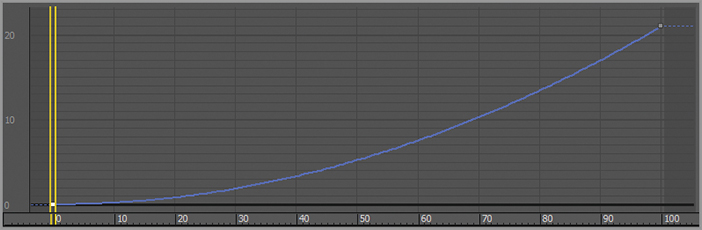

In Figure 5-9, the object slowly accelerates in an ease-out in the positive Z direction until it hits frame 100, where it suddenly stops.

Figure 5-8: The object quickly accelerates to an ease-in stop.

Figure 5-9: The object eases out to acceleration and suddenly stops at its fastest velocity.

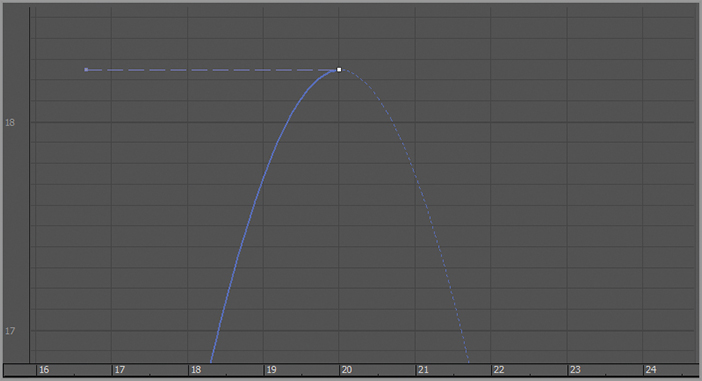

In Figure 5-10, the object eases in and travels to an ease-out where it decelerates, starting at around frame 69, to where it slowly stops, at frame 100.

Finally, in Figure 5-11, to showcase another tangent type, step interpolation makes the object jump from its Z Position in frame 20 to its new position in frame 21.

Figure 5-12 shows the Curve Editor, with its major aspects called out for your information.

Figure 5-10: Ease-out and ease-in

Figure 5-11: Step interpolation makes the object “jump” suddenly from one value to the next.

Figure 5-12: The Curve Editor

Refining the Animation

Let’s play the animation now. In the bottom right of the interface, you will see an animation player with the sideways triangle to signify Play. Select the Camera01 viewport and click the Play button. The framework of the movement is getting there. Notice how the speed of the ball is consistent. If this were a real ball, it would be dealing with gravity; the ball would speed up as it got closer to the ground and there would be “hang time” when the ball was in the air on its way up as gravity took over to pull it back down.

This means you have to edit the movement that happens between the keyframes. This is done by adjusting how the keyframes shape the curve itself, using tangents. When you select a keyframe, a handle will appear in the user interface (UI), as shown in Figure 5-13.

Figure 5-13: The keyframe’s handle

This handle adjusts the tangency of the keyframe to change the curvature of the animation curve, which in turn changes the animation. There are various types of tangents, depending on how you want to edit the motion. By default the Auto tangent is applied to all new keyframes. This is not what you want for the ball, although it is a perfect default tangent type to have.

Editing Animation Curves

Let’s edit some tangents to better suit your animation. The intent is to speed up the curve as it hits the floor and slow it down as it crests its apex. Instead of opening the Curve Editor through the menu bar, this time you are going to use the shortcut. Close the large Curve Editor dialog box, and then at the bottom-left corner of the interface, click the Open Mini Curve Editor button shown in Figure 5-14.

Figure 5-14: Click the Open Mini Curve Editor button.

The Mini Curve Editor is almost exactly the same as the one you launch through the main menu. A few tools are not included in the Mini Curve Editor toolbar, but you can find them in the menu bar of the Mini Curve Editor.

To edit the curves, follow these steps:

Figure 5-15: The effect of the new tangent type

Finessing the Animation

Although the animation has improved, the ball has a distinct lack of weight. It still seems too simple and without any character. In situations such as this, animators can go wild and try several different things as they see fit. Here is where creativity helps hone your animation skills, whether you are new to animation or have been doing it for 50 years.

Animation shows change over time. Good animation conveys the intent, the motivation for that change between the frames.

Squash and Stretch

The concept of squash and stretch has been an animation staple for as long as there has been animation. It is a way to convey the weight of an object by deforming it to react (usually in an exaggerated way) to gravity, impact, and motion.

You can give your ball a lot of flair by adding squash and stretch to give the object some personality. Follow along with these steps:

Figure 5-16: Use the Select And Squash tool to squash down the ball on impact.

Figure 5-17: The final curves

Setting the Timing

Well, you squashed and stretched the ball, but it still doesn’t look right. That is because the ball should not squash before it hits the ground. It needs to return to 100 percent scale and stay there for a few frames. Immediately before the ball hits the ground, it can squash into the ground plane to heighten the sense of impact. The following steps are easier to perform in the regular Curve Editor rather than in the Mini Curve Editor. So close the Mini Curve Editor by clicking the Close button on the left side of its toolbar.

Open the Curve Editor to fix the timing, and follow these steps as if they were law:

Figure 5-18: Enter a value of 100.

Once you play back the animation, the ball will begin to look a lot more like a nice cartoonish one, with a little character. Experiment by changing some of the scale amounts to have the ball squash a little more or less, or stretch it more or less to see how that affects the animation. See if it adds a different personality to the ball. If you can master a bouncing ball and evoke all sorts of emotions from your audience, you will be a great animator indeed.

Moving the Ball Forward

You can load the Animation_Ball_01.max scene file from the Bouncing Ball project on your hard drive (or from the companion web page) to catch up to this point or to check your work.

Now that you have worked out the bounce, it’s time to add movement to the ball so that it moves across the screen as it bounces. Layering animation in this fashion, where you settle on one movement before moving on to another, is common. That’s not to say you won’t need to go back and forth and make adjustments through the whole process, but it’s generally nicer to work out one layer of the animation before adding another. The following steps will show you how:

Figure 5-19: The X Position of the ball does not look right.

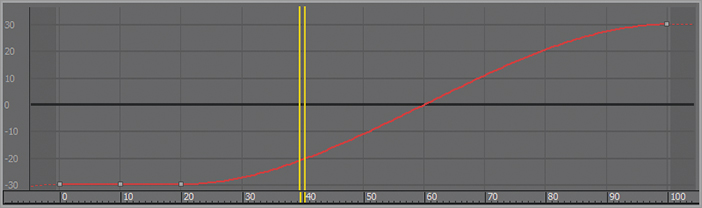

Figure 5-20 shows the proper curve.

Figure 5-20: The X Position curve for the ball’s movement now has no ease-out or ease-in.

Adding a Roll

You need to add some rotation, but there are several problems with this. One, you moved the pivot point to the bottom of the ball in the very first step of the exercise. You did that so the squashing would work correctly—that is, it would be at the point of contact with the ground. If you were to rotate the ball with the pivot at the bottom, it would look like Figure 5-21.

Figure 5-21: The ball will not rotate properly because the pivot is at the bottom.

Using the XForm Modifier

You need a pivot point at the center of the ball, but you can’t just move the existing pivot from the bottom to the middle—it would throw off all the squash and stretch animation. Unfortunately, an object can have only one pivot point. To solve the issue, you are going to use a modifier called XForm. This modifier has many uses. You’re going to use it to add another pivot to the ball in the following steps:

Now to be clear, this isn’t a pivot point. This is the center point on the XForm modifier. If you go to the modifier stack and click on the sphere, the pivot point will still be at the bottom.

The XForm modifier allows the ball to rotate without its squashing and stretching getting in the way of the rotation. By separating the rotation animation for the ball’s roll into the modifier, the animation on the Sphere object is preserved.

Animating the XForm Modifier

To add the ball’s roll to the XForm modifier, follow along with these steps:

The ball should be a rubbery cartoon ball at this point in the animation. Just for practice, let’s say you need to go back and edit the keyframes because you rotated in the wrong direction and the ball’s rotation is going backward. Fixing this issue requires you to go back into the Curve Editor as follows.

Figure 5-22: The XForm’s gizmo selected in the Controller window with the rotation of the ball set to Linear Tangents

Close the Curve Editor and play the animation. Play the bounce ball.avi movie file located in the RenderOutput folder of the Bouncing Ball project to see a render of the animation. You can also load the Animation_Ball_02.max scene file from the Bouncing Ball project to check your work.

- Bounce the ball on the floor and then off a wall. Try bouncing the ball off a table, onto a chair, and then onto the floor.

- Animate three different types of balls bouncing next to one another, such as a bowling ball, a ping pong ball, and a tennis ball. Examples may be found at www.sybex.com/go/3dsmax2013essentials.