CHAPTER TEN

Tax Procedures and Litigation

§ 10.1 Introduction

§ 10.2 Notice and Filing Requirements

(a) Notice to Governmental Agencies

(b) Local Insolvency Group Function

§ 10.3 Tax Determination

(a) Tax Liability

(i) S Corporations and Partnerships

(ii) Previously Determined Taxes

(b) Proof of Claim

(i) Filing Requirements

(ii) Timely Filed Proof of Claim

(iii) Amended Proof of Claim

(iv) Failure to Respond to Objection

(v) Proper Notice

(vi) Priority Taxes

(vii) Burden of Proof

(c) Tax Refund

(d) Determination of Unpaid Tax Liability

(e) Determination of Tax Aspects of a Plan

(i) Chapter 12

(ii) Other Plan Issues

(f) Effective Date

(g) Dismissal of Petition

(h) Tax Impact of Trusts Created in Chapter 11

(i) Tax Penalty in Bankruptcy Cases

(j) Effect of the Automatic Stay

(k) Tax Offset

(l) Assignment of Tax Refunds

(m) Waiver of Sovereign Immunity

(n) Offers in Compromise

(o) Impact of Settlement

§ 10.4 Bankruptcy Courts

(a) Jurisdiction

(b) Awarding Attorneys’ Fees

(c) Sole Agency Rule

(d) Tax Avoidance

§ 10.5 Minimization of Tax and Related Payments

(a) Estimated Taxes

(b) Prior-Year Taxes

(c) Pension Funding Requirements

§ 10.1 INTRODUCTION

The objective of this chapter and the next is to discuss the aspects of bankruptcy taxation that present special problems associated with the filing of tax returns and the payment and assessment of tax. This chapter contains a review of procedures for filing returns and determining taxes and the jurisdiction of the bankruptcy court.

The provisions of the Bankruptcy Code changed the tax procedures to be followed in a bankruptcy case, and some Internal Revenue Code (I.R.C.) sections were amended to conform to the provisions of the Bankruptcy Code. Additionally, the Internal Revenue Service reorganization that took place primarily in 2000 (resulting from the Internal Revenue Service Restructuring and Reform Act of 19981) also changed the tax procedures to follow in bankruptcy.

§ 10.2 NOTICE AND FILING REQUIREMENTS

(a) Notice to Governmental Agencies

Pursuant to I.R.C. section 6036, every trustee for a bankrupt estate, court-appointed receiver, assignee for the benefit of creditors, other fiduciary, and executor must give notice of qualification to the Secretary of the Treasury or a delegated representative in the manner and within the time limit required by regulations of the Secretary or delegate.

Regulations under section 301.6036-1(a)(1) provide that receivers, bankruptcy trustees, debtors in possession, and other like fiduciaries in a bankruptcy proceeding are not required to provide the appropriate district director2 with notice of appointment within 10 days of the date thereof.

Where written notice is required, it may be made on Treasury Form 56: Notice Concerning Fiduciary Relationship, and should include:

- The name and address of the person making such notice and the date of appointment or of taking possession of the assets

- The name, address, and employer identification number of the debtor or other person whose assets are controlled

In the case of a court proceeding, the following additional information may be required in a supplementary schedule:

- The name and location of the court in which the proceeding is pending

- The date on which the proceeding was instituted

- The number under which the proceeding is docketed

- The date, time, and place of any hearing, meeting of creditors, or other scheduled action with respect to the proceeding

Similar notices may be required by other governmental taxing authorities and should be filed in accordance with their prescribed procedures.

I.R.C. section 6903 requires that a fiduciary give the Treasury Department a notice of relationship (a statement that any person is acting for another in a fiduciary capacity). This notice is filed on Treasury Form 56. Once this notice has been filed, the trustee would have the right to file or amend prior years’ returns and act on behalf of the estate in other tax issues that might arise. Notice given under I.R.C. section 6036 would satisfy the requirement of I.R.C. section 6903.

If a required notice is not given as stipulated by I.R.C. section 6036, the period of limitations on the assessment of taxes is suspended from the date the proceeding is instituted to the date notice is received by the district director3 and for an additional 30 days thereafter. However, the suspension in no case shall exceed 2 years.4

(b) Local Insolvency Group Function

Chapter 11, chapter 12, business chapter 13, and chapter 7 cases with assets in the bankruptcy estate are handled by bankruptcy advisors in the IRS’s local insolvency groups. To facilitate control over the cases pending, the IRS may send a letter to the chapter 11 debtor explaining the returns to be filed, the location where tax returns should be filed, the location where notices should be sent, the procedures to be followed in making tax deposits, the restrictions a tax lien may place on the use of cash collateral, and other relevant information.

§ 10.3 TAX DETERMINATION

(a) Tax Liability

Section 505 of the Bankruptcy Code authorizes the bankruptcy court to determine the tax liability of a debtor, provided the tax issue had not been contested and adjudicated before the commencement of the bankruptcy case. Included would be any fine or penalty relating to a tax or any other addition to a tax.5 The bankruptcy court determines the tax claims allowed under section 502 of the Bankruptcy Code and the dischargeability of the tax under section 523 of the Bankruptcy Code. Section 505 of the Bankruptcy Code applies to all types of taxes, including income taxes, excise taxes, sales taxes, unemployment compensation taxes, and so on.

Section 505(c) provides:

Notwithstanding section 362 of this title, after determination by the court of a tax under this section, the governmental unit charged with responsibility for collection of such tax may assess such tax against the estate, the debtor, or a successor to the debtor, as the case may be, subject to any otherwise applicable law.

Thus, once the bankruptcy court has determined the tax liability under section 505, the IRS can assess the tax against the debtor or, if the petition is filed by an individual, against the estate. Collection would be delayed by the automatic stay. The Tenth Circuit6 held that a transferee liability under section 6901(a) is a tax liability of the estate. The National Office of the IRS issued a “policy statement” change indicating that it would issue prompt determination letters only on returns for which there is a tax liability. In Revenue Manual 4.27.5-2 and 3, the IRS takes the position that a tax return from a partnership or from an S corporation is not subject to tax and as a result the request for tax determination does not apply. The IRS also noted that the 2005 Act provides that the stay under section 362(a)(8) is revised to apply only to a tax liability for an individual for a taxable period ending before the order for relief or for a corporation for a period for which the bankruptcy court may determine the tax. Thus, the tax liability arising after the petition is filed for an individual may be determined by tax authorities other than the bankruptcy court. However, the bankruptcy court retains jurisdiction for both prepetition and postpetition taxes of a corporation. See § 4.4(f).

(i) S Corporations and Partnerships

Excerpts from the IRS response to a request for tax determination for a partnership or S corporation follow.

On (date ), you requested a prompt determination of tax liability as shown on Form 1120S under Bankruptcy Code section 505(b) for the bankruptcy estate of (S corporation name), for the period ending (YYMM). Under section 505(b) of the Bankruptcy Code, the trustee, the debtor, and any successor to the debtor are discharged from any liability for such tax upon payment of the tax shown on such return if the trustee is not notified within 60 days after such request that such return has been selected for examination. The return you submitted is not being selected for examination under this provision. However, the trustee, the debtor, and any successor to the debtor is not discharged under section 505(b) if the return is fraudulent or contains a material misrepresentation. With limited exceptions, S corporations filing Form 1120S returns do not incur any income tax liabilities. The exceptions apply to S corporations with prior C corporation history. Further, the income tax liability in such instances is limited to recapture of tax credits, tax on built in gains, and tax on excessive passive investment income under IRC sections 1371(d), 1374, and 1375, respectively. Under IRC section 1363(d), the S corporation may also be liable for the last three of four payments related to LIFO recapture included on the final C corporation tax year return. Since there is no indication from the material submitted that there is a prior C corporation history, it appears that the bankruptcy estate did not incur any income tax liability. The Form 1120S return you submitted has not been selected for examination under the prompt audit procedures of section 505(b). Accordingly, unless the return is fraudulent or contains a material misrepresentation, the trustee, the debtor, and any successor to the debtor will be discharged from any tax liability for such return under section 505(b). Please note that the decision not to select this return for examination under the prompt audit procedures does not preclude future audit of the return. However, if there is an audit of the Form 1120S submitted with the request, any income tax consequences will apply to the shareholders only.

A similar form letter is contained in Internal Revenue Manual 4.27.5-2 for partnerships.

Even though the IRS no longer issues determination letters for partnerships and S corporations, it is still advisable for the debtor to request such a letter and properly document the request. For example, in In re First Securities Group of California, Inc.,7 the bankruptcy court considered the request valid over the objection of the IRS.

First Securities Group of California, an S corporation, requested the IRS to determine the tax under section 505(b) for calendar year 1996. The IRS rejected the trustee’s request for a prompt determination, stating that the provisions of section 505(b) apply only to returns for which there is a tax liability, and generally, the partnership and S corporation show no tax liability. The IRS argued that the National Office of the IRS has issued a “policy statement” change that it would issue prompt determination letters only on returns for which there is a tax liability. The trustee noted that the IRS policy statements do not have the force and effect of law and are not binding on the bankruptcy court. See In re Technical Knockout Graphics, Inc.,8 where the Bankruptcy Appellate Panel (BAP) held that the bankruptcy court was not bound to apply voluntary-involuntary dichotomy as set forth in the IRS policy statement in determining allocation of tax payments pursuant to section 505 of the Bankruptcy Code. The court reasoned that “holding to the contrary would allow IRS policy statements to limit the exercise of the bankruptcy court’s equitable jurisdiction, a result inconsistent with the history and intent of bankruptcy legislation.” However, the Ninth Circuit reversed the decision of the BAP and held that the payments are involuntary and the bankruptcy court does not have equitable jurisdiction to order otherwise.

The bankruptcy court in Securities Group of California held that the estate had no unpaid tax liability for the calendar year 1996 and that the S corporation and the trustee were discharged from any liability for unpaid federal income taxes for 1996. The court also held that

as a result of the Trustee’s February 1997 filing of a request for prompt determination pursuant to 11 U.S.C. section 505(b) of the final tax return (“Return”) filed by the First Securities Estate for calendar year ending December 31, 1996, and the IRS’s failure to notify the Trustee that the Return was subject to audit within 60 days of the prompt determination request, as well as its failure to complete an examination within 180 days of the Trustee’s request, the Internal Revenue Service shall be precluded from hereafter auditing the Return.

In one case,9 the bankruptcy court held that the Tax Court could determine the tax liability. The bankruptcy court, in reaching this decision, concluded that the Tax Court could better immunize the IRS against a potential whipsaw effect by consolidating this case with the taxpayer’s related cases. The bankruptcy court established a date on which it would hear the case if either party delayed the proceedings without good cause. Once both parties were ready for trial, the bankruptcy court indicated that it would then modify the automatic stay to permit trial.

(ii) Previously Determined Taxes

Section 505(a) of the Bankruptcy Code provides that the bankruptcy court may determine the tax liability, except in cases where the tax has been previously determined by a “judicial or administrative tribunal of competent jurisdiction” before the filing of the petition. In In re Doerge,10 the debtor contended in bankruptcy court that the three-year period for assessment following the filing of his returns for these years had expired before he filed his tax court petition challenging the government’s notices of deficiency. As a result, the debtor claimed that “the government was barred from assessing these taxes following the tax court’s decision, and the resulting tax liens, which arose by operation of law following such assessment, are void and cannot be enforced against his property in rem.” The court noted that a discharge in bankruptcy only relieves a debtor of personal liability for his obligations, as set forth in section 524(a)(2) of the Bankruptcy Code, and does not automatically invalidate liens securing such dischargeable debts. Rather, according to the court, “these liens continue beyond bankruptcy as a charge upon the debtor’s property if not disallowed or avoided.”11

The court noted that section 505(a)(2)(A) of the Bankruptcy Code and the doctrine of res judicata preclude the court from redetermining tax liabilities that were determined in the Tax Court proceeding. The court then concluded that “[s]ince the debtor cannot question the legality of these taxes based on expiration of the limitations period prior to the tax court proceeding, the debtor is likewise precluded from questioning the validity of the tax liens that arose from the government’s timely assessment following entry of the tax court decision.” Thus the court concluded, “even though the tax liabilities themselves are dischargeable in bankruptcy, the resulting tax liens are valid and enforceable against the debtor’s property in rem.”

The bankruptcy court held that it will not determine the tax liability of a chapter 7 debtor while other administrative and legal remedies—not requiring the payment of the tax—remain open.12 The taxpayer filed a chapter 7 petition and commenced an adversary proceeding against the United States asking the bankruptcy court to determine:

- Amount of his federal tax liability

- That the liability was dischargeable

- That the tax lien on his property was invalid

The court ruled that the fact that the taxpayer’s estate had no assets was irrelevant because the bankruptcy court regularly adjudicates lien claims in no-asset cases. The court held that as long as other administrative and legal remedies remained open to challenge the claim, the taxpayer was required to exhaust those remedies, as they were designed specifically to deal with the issues the taxpayer raised. The court noted that if the taxpayer could not get relief elsewhere without paying the tax, the bankruptcy court would hear his case.

The bankruptcy court has the authority to determine tax liability to be assessed against a responsible person for trust fund–type taxes.13 However, the bankruptcy court in the no-asset case abstained because determination of the taxpayer’s liability would have no effect on the administration of the bankruptcy case. The court explained that no bankruptcy issues were involved, as the taxpayer conceded that the tax debt would be nondischargeable if she were found to be liable. The court noted that a ruling would have no effect on the administration of the no-asset case and that the taxpayer could challenge her liability for the taxes administratively and in district court.

The bankruptcy court held that the debtor in a chapter 7 case lacks standing to object to creditor claims or to compel the trustee to object to a proof of claim.14

The bankruptcy court may determine the existence and amount of an alleged settlement with the IRS.15

The Eleventh Circuit held that the bankruptcy court lacked jurisdiction to determine the withholding tax liability of entities other than the debtor.16 In Brandt-Airflex, the issue dealt with whether the bankruptcy court could determine the liability of Long Island Trust for trust fund taxes Brandt did not pay.

In In re Ralph C. McAuley,17 the district court reversed the bankruptcy court, which had held that it had the jurisdiction to determine the tax liability of a husband and wife even though only the husband had filed the petition. The bankruptcy court found that the wife is an indispensable party. However, the bankruptcy court dismissed the part of the wife’s suit that sought to hold the alleged tax liability of the wife dischargeable and would not enjoin the IRS from assessing and collecting the tax. The bankruptcy court noted that the couple could amend the petition to include the wife.

The bankruptcy court relied on the bankruptcy court’s decision in the Brandt-Airflex case, which was subsequently reversed by the district court and upheld by the Second Circuit. The district court, in reversing the bankruptcy court, noted that all courts that have considered this issue recently have concluded that section 505(a) of the Bankruptcy Code does not extend the bankruptcy court’s jurisdiction to parties other than the debtor.

In Kroh v. Commissioner,18 the Tax Court held that the IRS is not barred from proceeding against the spouse for a tax liability on a previously filed joint tax return where the bankrupt spouse settled the tax liability.

The Tax Court rejected the taxpayer’s argument that the IRS’s settlement with her husband, and the subsequent assessment and collection of that amount, barred the IRS as a matter of law from litigating her tax liabilities. Citing I.R.C. section 6013(d)(3), the court noted that the tax liability of a husband and wife who file a joint return is joint and several and that common-law rules apply. The court concluded that Kroh’s position was analogous to that of the taxpayer in Dolan v. Commissioner,19 where the court held that a prior assessment against an individual does not have the effect of reducing a deficiency determined against the individual’s spouse merely because the two filed joint returns.

Kroh’s contention that the IRS was barred from litigating her tax liabilities by the doctrines of res judicata or collateral estoppel was rejected by the court. The court concluded that tax claims against Kroh and her husband were two separate causes of action and Kroh was not a party or privy of her husband in the bankruptcy court. In addition to Dolan, the court cited Tavery v. United States.20

Tax claims that are determined by a bankruptcy court in a dismissed case may not be relitigated in the Tax Court.21 In Samuel Leroy Bostian v. Commissioner,22 it was also held that the bankruptcy court determination of taxes is valid even if the case is dismissed.

In In the matter of East Coast Brokers & Packers (ECBP),23 the bankruptcy court held that the state statute of limitations does not bar the debtor’s objection to state tax claims. The bankruptcy court held that the bankruptcy court has the authority and jurisdiction under section 505 of the Bankruptcy Code to consider ECBP’s objection and that section 505(a)(2) does not interfere with the bankruptcy court’s authority to consider the matter, because the liability was not previously contested or adjudicated by another tribunal.

Several other courts have followed East Coast Brokers & Packers, and the other cases that allowed the hearing on the tax issues involved a determination of an unpaid tax liability, rather than a request for a refund. Some courts have been reluctant to extend the time period for a refund under section 505(a)(2)(B).24

Section 505(a)(2) provides that the court may not determine an ad valorem tax if the applicable period for contesting or redetermining the amount under any law, other than bankruptcy law, has expired. Some bankruptcy courts have redetermined the tax because the bankruptcy court may determine all claims. By not allowing the bankruptcy court to determine the ad valorem tax claim, the change allows a governmental unit to collect a tax that is greater than the amount allowed. If the tax is properly determined, the state will receive its priority payment. For example, in one case where a chapter 11 trustee was appointed, the debtor allegedly borrowed millions of dollars of debt under false pretenses. The debtor did not file business tax forms, and the taxing unit determined the tax based on values that were significantly greater than the actual values of the assets. Under this provision, because the time for redetermining the tax expired, the business tax would remain, even though all parties knew the tax was incorrectly calculated. Taxes already have a priority over all other general unsecured claim holders, and this change will allow the taxing authority to collect or retain taxes for amounts that are greater than the amount that should be allowed.

Section 505(b) provides for the clerk of each district to maintain a listing under which a federal, state, or local governmental unit responsible for collecting taxes within the district may designate an address for service of requests and describe further information concerning additional requirements for filing such requests. If a governmental unit fails to provide an address to the clerk, requests should be served at the address for filing returns or protests with the appropriate taxing authority of that governmental unit. Tax returns and other notices should be filed with the address provided by the clerk in the appropriated district.

Revenue Procedure (Rev. Proc.) 2002-2625 is to be followed in determining the priority of taxes. In In re Salvatore Barranco,26 the debtor attempted to reopen a chapter 7 case with a section 505 motion asking the bankruptcy court to allocate all of the payments to taxes for all years first and then to penalties and interest. The IRS made the allocation in accordance with Rev. Proc. 2002-26 providing that in a situation where the taxpayer does not provide specific written instructions on the application of the payments, the IRS will apply payments to tax, penalties, and interest for each successive year, beginning with the earliest year’s tax liability. The bankruptcy court cited Sotir v. United States,27 which held that if the taxpayer does not provide instruction as to how to allocate the payments, the IRS may allocate the voluntary payments in any manner it desires. The bankruptcy court dismissed the motion for determination of the tax liability because it was contrary to the procedures set forth in Rev. Proc. 2002-26.

Once the plan has been confirmed, it is generally difficult to convince the court to consider other issues, such as the determination of taxes, including the determination of whether the taxpayer is subject to a postconfirmation tax refund. When a debtor confirms a chapter 11 plan, it should begin cutting the ties with the bankruptcy process at the same time.28

A debtor was allowed to pursue his tax claim in a reopened chapter 7 case.29 In the reopened chapter 7 filing, the debtor filed an amended tax return for 1987, asserting that business debt forgiven, reported by the trustee as income, was not taxable income under I.R.C. section 108. The Third Circuit, reversing a district court, held that a chapter 7 debtor had standing to pursue his tax claim. The Third Circuit rejected the IRS’s assertion that only the bankruptcy trustee could sue for refund because the debtor had failed to schedule the tax claim explicitly as an asset of the estate and that any refund granted to the debtor was therefore erroneous and could be recovered. The Third Circuit noted that the debtor could not have scheduled the tax refund separately at the time of his bankruptcy filing, because the refund was not yet a known asset. According to the Third Circuit, the IRS could not prevail, because it took no position in the district court on the underlying validity of the refund. The court suggested that the debtor “must consider himself the fortunate beneficiary of the litigation strategy” followed by the IRS.

In In re Brulotte,30 the bankruptcy court sustained the objection made by Richard and Sandra Brulotte to the IRS’s proof of claim for $34,000. The Brulottes objected to the claim, alleging that their tax debt had been satisfied when they surrendered the equipment from their failed tavern to the IRS, which sold the property. On appeal, the Ninth Circuit BAP reversed, ruling that the testimony was inadmissible and that there was insufficient other evidence to establish that the Brulottes had satisfied their tax liability.

The Brulottes appealed to the Ninth Circuit, and the decision was again reversed. The Ninth Circuit found sufficient evidence to support the factual finding of the bankruptcy court that the Brulottes had paid off their tax debt by turning over the restaurant equipment to the IRS. The Ninth Circuit noted that the bankruptcy court was free to credit the Brulottes’ testimony, especially in light of the absence of contradicting evidence.

As a general rule, the bankruptcy court does not determine the amount or the dischargeability of a tax claim in “no-asset” cases.31 However, the failure of the bankruptcy court to rule on tax issues of no-asset cases involving individuals can place a burden on the individuals. To pursue the tax issue in the district courts or claims court, a taxpayer must pay the tax and then sue for a refund. Often the deadline for taking action in the Tax Court passes and no funds are available to make the payment; thus, the only avenue for determination of the tax is in the bankruptcy court. Because of this situation, bankruptcy courts have decided to rule on the issues in deserving cases, often over the objection of the IRS or other taxing authorities. For example, in In re Anderson,32 the court noted that “the issue simply is whether or not this Debtor owes the tax liability that has been assessed—not whether it should be litigated in another court.”33

The BAP34 held that the debtor could not use section 502(c) of the Bankruptcy Code to estimate a postpetition administrative tax claim, because that section applies only to prepetition claims. The court found that proper statutory construction requires that administrative tax liability be determined under section 505. The BAP therefore reversed the bankruptcy court’s cap on the amount of tax liability. The BAP also determined that the appeal was not moot simply because the IRS did not obtain a stay pending appeal and the receiver had distributed the assets of the bankruptcy estate.

A U.S. district court35 has denied the government’s request to prosecute its lien priority case against a healthcare finance company in district court rather than in bankruptcy court on the basis that no substantial and material consideration of nonbankruptcy law was necessary. Additionally the district court noted that bankruptcy court was familiar with the case.

(b) Proof of Claim

Section 501 of the Bankruptcy Code permits a creditor or indentured trustee to file a proof of claim and an equity holder to file a proof of interest. If the taxing authority does not file a proof of claim, the debtor, trustee, or any other party who may be liable for the taxes may file a proof of claim for the taxing authority. However, if the creditor subsequently files a proof of claim, it supersedes the one filed by another party on behalf of such creditor.

(i) Filing Requirements

Bankruptcy Rule 3002 provides that an unsecured creditor or an equity holder must file a proof of claim or interest for the claim or interest to be allowed in a chapter 7 or chapter 13 case. For the claim to be allowed under section 502 or 506(d) of the Bankruptcy Code, a secured creditor needs to file a proof of claim, unless a party in interest requests a determination and allowance or disallowance. In a chapter 7 or chapter 13 case, a proof of claim is to be filed within 90 days after the date set for the meeting of creditors under section 341(a) of the Bankruptcy Code. For cause, the court may extend this period and will then fix the time period for the filing of a proof of a claim arising from the rejection of an executory contract. The filing of the proof of claim is not mandatory in a chapter 9 or chapter 11 case, provided the claim is listed in the schedule of liabilities. However, if the claim is not scheduled or the creditor disputes the claim, a proof of claim should be filed. It is generally advisable to file a proof of claim even though the claim is scheduled (see Bankruptcy Rule 3003). A proof of claim filed will supersede any scheduling of that claim in accordance with section 521(1) of the Bankruptcy Code.

According to Bankruptcy Rule 1019(4), claims that are filed in a superseded case are deemed filed in a chapter 7 case. Thus, in a case that is converted from chapter 11 to chapter 7, it will not be necessary for the creditor to file a proof of claim in the chapter 7 case if one was filed in the chapter 11 case. However, if the debt was listed on the schedules in a chapter 11 case and a proof of claim was not filed, it will be necessary to file a proof of claim if the case is converted to chapter 7.

A district court would not allow a challenge to a proof of claim filed by the IRS solely for delinquent child support but rather held that the couple must challenge that claim in state (Nebraska) court.36

(ii) Timely Filed Proof of Claim

The general rule is that a creditor in chapter 7 or chapter 13 must file a proof of claim within 90 days after the first date set for the meeting of creditors under section 341 of the Bankruptcy Code. However, the time period of the filing of a proof of claim by a governmental unit is different. The Bankruptcy Reform Act of 1994 amended section 502(b) of the Bankruptcy Code to provide that a claim of a governmental unit, including tax claims, will be considered timely filed if it is filed before 180 days after the order for relief or such later time as the Federal Rules of Bankruptcy may provide. The Act also provides that a proof of claim not timely filed, except for the government claim mentioned above and tardy claims permitted under section 726 of the Bankruptcy Code, will not be allowed. These changes are effective for petitions filed after October 22, 1994.

The 2005 Act provides an exception to the special 180-day time period granted to the taxing authorities by providing that under chapter 13, a claim of a governmental unit for a tax with respect to a return filed under section 1308 shall be timely if the claim is filed on or before the date that is 60 days after the date on which such return was filed as required.

The 2005 Act amends section 726(a)(1) of the Bankruptcy Code to allow a tardy claim under section 507 to be entitled to a distribution provided such claim is filed the earlier of the date that is 10 days following the mailing to creditors of the summary of the trustee’s final report or before the trustee commences final distribution.

As a general rule, late-filed proof of claims may be allowed either as amendments under Fed. R. Bankr. P. 7015 or pursuant to the bankruptcy court’s exercise of equitable discretion under section 105 of the Bankruptcy Code. In In re Pettibone Corp.,37 the bankruptcy court considered the following items set forth in the Seventh Circuit38 in deciding if the claim should be allowed:

- Whether the debtors and creditors rely on the government’s earlier proofs of claim or whether they instead have reason to know that subsequent proofs of claim would follow on completion of audit

- Whether the other creditors would receive a windfall to which they are not entitled, on the merits, by the court not allowing this amendment to the IRS’s proof of claim

- Whether the IRS intentionally or negligently delays in filing the proof of claim stating the amount of taxes due

- The justification, if any, for the failure of the IRS to file for a time extension for the submission of further proofs of claim pending an audit

- Whether there are any other considerations that should be taken into account in assuring a just and equitable result

The court concluded that because the debtor had been aware of the possibility that the IRS might increase the amount of its timely filed claim because of an ongoing examination, the court increased the time period for the IRS to file its claims even though the bar date had passed.

A district court has affirmed a bankruptcy court decision disallowing the government’s proof of claim on the basis that it was not timely filed, ruling that the lower court properly declined to equitably toll the 180-day period in Bankruptcy Rule 3002(c)(1).39 Because the government had not alleged that any outside action prevented it from filing its claim or that the taxpayer or the bankruptcy court negligently misinformed it of the filing deadline, the district court noted that the government should have requested additional time to file its claim and that it cannot cry foul for its own inexcusable neglect.

In a chapter 12 case, proper notice was sent listing the creditor based on an Illinois state court judgment and notifying the creditor of the deadline for filing the proof of claim. The creditor allowed the date to pass without filing a proof of claim. Eleven months later the bankruptcy court allowed the creditor to file its late claim. The district court reversed and the Seventh Circuit affirmed the district court’s decision on the basis that the late claim was statutorily barred.40

Employment taxes were owed to the Employment Division of the Department of Human Resources of Oregon, which was notified by the bankruptcy court that a bankruptcy petition had been filed but that the debtor had not registered with the agency as required by law. After the deadline, the agency filed a proof of claim. The court indicated the fact that the creditor was not aware of the nature of the claim or that they had one was not determinative. The tax claim was subordinated because the claim was untimely filed when the creditor had notice of the bankruptcy even though it was unaware of the nature of its claim against the debtor.41

In In the matter of Eddie Burrell,42 the bankruptcy court held that a deficiency notice did not constitute a proof of claim and that a proof of claim need not be filed for the secured part of the debt. The court cited In re Simmons43 for the general rule that the filing of a proof of claim is not required by a creditor asserting a secured claim. In In re Leightner,44 the bankruptcy court held in a chapter 13 case that an unsecured claim should be disallowed when filed late. In In re Hausladen,45 the bankruptcy court held that late-filed, unsecured claims should not be disallowed, interpreting the bankruptcy rules as simply determining whether claims are timely or late, rather than whether they should be allowed or disallowed.

(iii) Amended Proof of Claim

The IRS has been allowed to file an amendment to a proof of claim even if the bar date has passed, provided the original proof of claim was timely filed in certain situations. In In re Homer R. Birchfield,46 the court allowed the IRS to file an amended proof of claim to reflect an agreement reached with the trustee.

Generally, the IRS has not been allowed to amend a proof of claim to include years that were not contained in the original proof of claim. For example, in United States v. Howard E. Owens,47 the district court upheld the bankruptcy court’s decision that would not allow a proof of claim file in a chapter 13 case for 1983 to include the amount due for 1981 even though the tax return for 1981 was filed after the bar date. The bankruptcy court cited three factors it considered: (1) the absolute nature of the policy barring late filings, (2) the failure of the IRS to ask for an extension, and (3) the equitable factors enunciated in In re Miss Glamour Coat Co., Inc.48 The court emphasized, however, that the first two factors alone were enough to justify the preclusion of the 1981 claim. However, the bankruptcy court reached a different decision in In re Roderick.49 The bankruptcy court allowed an amended claim filed after the bar date to be filed and held that the IRS was entitled to distribution as a timely filed claim, even though the proof of claim was for only one tax year and the amended proof of claims was for three years. The court held that the amended claim related back to the IRS’s timely filed claim. The bankruptcy court cited rule 15(c)(2) of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure and noted that the original claim and the amended claim all related to income taxes. The court also noted that the delay by the IRS was not undue because the bankruptcy trustee knew that the IRS had asserted a claim for taxes for the years for which a return had not been filed, and the trustee suffered no prejudice.

Additionally, the IRS may not be allowed to amend the proof of claim if it is materially greater than the amount reflected in the original proof of claim. For example, in In the matter of Emil Stavriotis,50 the Seventh Circuit would not allow the IRS to amend the proof of claim for 1981 and 1984 income taxes, which had been filed for $11,133. After completing an audit of the 1981 taxes, the IRS attempted to amend the return to over $2.4 million. The Seventh Circuit, in a divided decision, noted that the disposition of the motion to amend a proof of claim rests with the bankruptcy court and found equitable reasons to deny the amendment, including prejudice to other creditors that had no notice of the IRS’s audit and the justification for the government’s delay. However, the bankruptcy court held that the IRS’s amended proofs of claim, filed after the bar date, were not time-barred where the increase in the amount of the claims was not so dramatic as to surprise the debtor where the debtor had knowledge of the potential claim.51 However, the bankruptcy court held that the IRS may not amend, after the bar date, a proof of claim that was an unjustified estimate of the claim.52

(iv) Failure to Respond to Objection

The IRS may find that the claim has been disallowed after it fails to respond to an objection to the claim, as the bankruptcy court ruled in In re Hunt Brothers Construction, Inc.53 The taxpayer filed a chapter 11 petition, and the IRS filed a timely proof of claim and later amended it. After the amendment to the proof of claim was filed, the debtor converted the case to chapter 7 in December 1982. In July 1984, the IRS amended its claim again. In August 1987, the trustee of the chapter 7 case objected to the government’s claim and the IRS did not respond to the objection. Because the IRS did not respond to the objection, the trustee sought an order disallowing the claim on October 1, 1987. The court also ruled against the government’s objection because the trustee used a preprinted objection form rather than a motion and a disallowance order is valid even if signed by the clerk.

Failure to attend a hearing may also result in an objection being sustained and the claim not being allowed.54

(v) Proper Notice

Bankruptcy Rules 9014 and 7004(b) provide that the U.S. Attorney for the district in which the action is brought and the U.S. Attorney General must be notified. On appeal, the district court ruled that, because the creditors’ committee failed to properly notify the U.S. Attorneys, the tax claims must be considered on their merits. The bankruptcy court’s disallowance of the claims was reversed.

In a similar case,55 the trustee notified the IRS (and the agent who had filed an amended proof of claim) of the trustee’s objection to the amendment. The bankruptcy court held a hearing, and after the IRS failed to argue on the merits of the trustee’s objections, the court disallowed the amended claim. On appeal, the district court reversed the bankruptcy court’s order striking the government’s amended claim, on the ground that there was no justifiable excuse for improper service on the U.S. Attorney General.

In In re Allan Ray Johnson,56 the taxpayer failed to provide notice to the IRS and the Colorado Department of Revenue to allow both agencies timely filing of their respective claims and objection to, or participation in, the bankruptcy proceedings and confirmation of the plan. The court drew its conclusion from the deficiencies described in the case, such as the debtor’s failure to mail the amended plan, motion to confirm the (amended) plan, and notice of hearing to the Colorado Department of Revenue or to the IRS at a specific and appropriate IRS office address (preferably to the attention of a designated department, or an authorized person’s attention) or in accordance with local court requirements. Section 505(b) is modified by the 2005 Act to provide for the clerk of each district to maintain a listing under which a federal, state, or local governmental unit responsible for collecting taxes within the district may designate an address for service of requests and describe further information concerning additional requirements for filing such requests. If a governmental unit fails to provide an address to the clerk, requests should be served at the address for filing returns or protests with the appropriate taxing authority of that governmental unit.

Bankruptcy Rule 2002(J) provides the following regarding notices in bankruptcy cases to the IRS:

Copies of notices required to be mailed to all creditors under this rule shall be mailed (1) in a chapter 11 reorganization case, to the Securities and Exchange Commission at any place the Commission designates, if the Commission has filed either a notice of appearance in the case or a written request to receive notices; (2) in a commodity broker case, to the Commodity Futures Trading Commission at Washington, D.C.; (3) in a chapter 11 case, to the Internal Revenue Service at its address set out in the register maintained under Rule 5003(e) for the district in which the case is pending; (4) if the papers in the case disclose a debt to the United States other than for taxes, to the United States attorney for the district in which the case is pending and to the department, agency, or instrumentality of the United States through which the debtor became indebted; or (5) if the filed papers disclose a stock interest of the United States, to the Secretary of the Treasury at Washington, D.C.

Bankruptcy Rule 5003(e) provides:

(e) Register of mailing addresses of federal and state governmental units and certain taxing authorities.

The United States or the state or territory in which the court is located may file a statement designating its mailing address. The United States, state, territory, or local governmental unit responsible for collecting taxes within the district in which the case is pending may also file a statement designating an address for service of requests under § 505(b) of the Code, and the designation shall describe where further information concerning additional requirements for filing such requests may be found. The clerk shall keep, in the form and manner as the Director of the Administrative Office of the United States Courts may prescribe, a register that includes the mailing addresses designated under the first sentence of this subdivision, and a separate register of the addresses designated for the service of requests under § 505(b) of the Code. The clerk is not required to include in any single register more than one mailing address for each department, agency, or instrumentality of the United States or the state or territory. If more than one address for a department, agency, or instrumentality is included in the register, the clerk shall also include information that would enable a user of the register to determine the circumstances when each address is applicable, and mailing notice to only one applicable address is sufficient to provide effective notice. The clerk shall update the register annually, effective January 2 of each year. The mailing address in the register is conclusively presumed to be a proper address for the governmental unit, but the failure to use that mailing address does not invalidate any notice that is otherwise effective under applicable law.

Effective January 2, 2011, the IRS established two national addresses for the receipt of most insolvency mail, one for trustee remittances and another for administrative mail. Chapter 7 and chapter 13 payments are to be sent to Insolvency Remittance, Post Office Box 7317, Philadelphia, PA 19101-7317. Administrative mail, such as court documents, forms, general correspondence, and most other bankruptcy-related communications, should be sent to Centralized Insolvency Operation, Post Office Box 7346, Philadelphia, PA 19101-7346. Overnight Mail should be sent to IRS, 2970 Market Street, Philadelphia, PA 19104.

These addresses were published in Internal Revenue Manual 5.9,11 Insolvency Mail Processing. As noted in Bankruptcy Rule 5003(e), the IRS is to update the register annually. Practitioners should check with the manual at the beginning of each year to see if changes have been made in the address for notices.

The Ninth Circuit BAP held, in In re Williams,57 that an order reducing a claim of the IRS resulting from an objection by the taxpayer may be amended or altered if the notice to the IRS was improper. The BAP held that the taxpayers provided the wrong notice of objection and that they failed to properly serve the notice and motion as required by the federal government. The BAP noted that the proper notice was 30 days pursuant to Bankruptcy Rule 3007, not the 10-day notice given by the Williamses under the local court rules.

The Fifth Circuit held that the confirmation of a plan does not substitute for a section 505 motion any more than it substitutes for an objection to a proof of claim.58 The circuit court noted that the debtor failed to invoke the bankruptcy court’s power to determine a tax debt, and the listing of the tax in his schedules, disclosure statement, and plan did not invoke that power.

The lesson from these cases is that proper notices must be served before the courts may adjust claims of taxing units.

The Tenth Circuit held, in Donald W. Fairchild v. Commissioner,59 that the taxpayer could not unilaterally withdraw his objection to a proof of claim and thereby dismiss the contested matter. The taxpayer attempted to withdraw his objection the day before the bankruptcy court was to hold a hearing on the innocent spouse issue.

In In re Bisch,60 the Ninth Circuit BAP held that there is no requirement in the I.R.C. or the Bankruptcy Code that the IRS file a proof of claim for a secured tax lien. The court also concluded that the IRS did not waive its secured status by failing to file a proof of claim. The BAP pointed out that failure to file a proof of claim may mean that a creditor does not receive a distribution from the debtor’s estate; however, the property is still liable for satisfaction of the debt. Citing In re Junes,61 the court explained that, where a debtor fails to provide for an IRS lien in a chapter 13 case, the tax lien survives the bankruptcy process unaffected.

As noted, section 505(b) is modified by the 2005 Act to provide for the clerk of each district to maintain a listing under which a federal, state, or local governmental unit responsible for collecting taxes within the district may designate an address for service of requests and describe further information concerning additional requirements for filing such requests. If a governmental unit fails to provide an address to the clerk, requests should be served at the address for filing returns or protests with the appropriate taxing authority of that governmental unit.

Taxing authorities need to be notified of bankruptcy filings. This provision should be helpful especially for state and local taxes, where there is considerable uncertainty as to where to file the notice.

(vi) Priority Taxes

In In re Pacific Atlantic Trading Co.,62 the Ninth Circuit held that the IRS’s priority claim, for which a proof of claim was filed over one year late, was allowed under the Bankruptcy Code and thus the IRS retained its right to first distribution, regardless of when it filed the proof of claim. The circuit court noted that 11 U.S.C. section 726(a)(l) does not distinguish between timely and late priority claims and, therefore, the IRS’s failure to comply with the time limits established in Bankruptcy Rule 3002(c) did not affect the tax claim’s entitlement to first-priority distribution. The Ninth Circuit noted that Rule 3002(c) simply divides claims into two categories, (1) timely and (2) late, but does not disallow a late claim. In April 1994, the Second Circuit, in In re Vecchio,63 also ruled that the bar date for claims provided in Bankruptcy Rule 3002 is void as to priority claims in a chapter 7 case, because 11 U.S.C. section 726(a)(1) does not distinguish between timely and untimely filed priority claims.

In In re Chavis,64 the IRS received notice when John and Betty Chavis filed their chapter 13 petition in May 1991. The IRS filed a proof of claim for 1989 and 1990, and the bankruptcy court confirmed the couple’s chapter 13 plan three days later, setting September 24, 1991, as the last day for creditors to file timely proofs of claim. Prior to this date, the IRS filed an “amendment” to its original proof of claim for a priority unsecured tax claim that included the previously filed amounts for 1989 and 1990, as well as listing liabilities for 1988 and 1991, for which the IRS sought priority unsecured status. The bankruptcy court disallowed the IRS’s 1988 tax liability claim, concluding that Bankruptcy Rule 3002(c) establishes a bar date for filing certain proofs of claim in chapter 13 cases. The bankruptcy court concluded that the IRS’s amended claim was filed after the bar date and was thus untimely filed because it was not an amendment to the proof of claim filed earlier but rather a new claim. The district court affirmed on appeal.

The Sixth Circuit affirmed, holding that the lower courts properly disallowed the IRS’s late filed claim. The Sixth Circuit reached this decision in conflict with the decisions of the Second Circuit in In re Vecchio and the Ninth Circuit in In re Pacific Atlantic Trading Co. Both of these courts allowed tardy claims in chapter 7 cases. The Sixth Circuit noted that these cases were decided on the rationale that conflicts between the Bankruptcy Code and the Bankruptcy Rules must be decided in favor of the Code. The Bankruptcy Code does not disallow tardy claims. The Sixth Circuit concluded that the Bankruptcy Code and Rules could be harmonized, noting that compliance with the timeliness requirement of Bankruptcy Rule 3002 is a prerequisite to the allowance of a proper claim under Bankruptcy Code section 502.

In disallowing the late filing of the proof of claim, the Sixth Circuit pointed to fundamental differences between chapter 7 and chapter 13 bankruptcies that limit the decisions in Vecchio and Pacific Atlantic Trading to chapter 7–type cases. The Sixth Circuit noted that chapter 13 serves as a flexible vehicle for the repayment of allowed claims and that all unsecured creditors seeking payment under a chapter 13 plan must file their claims on a timely basis so that the efficacy of the plan may be determined in light of the debtor’s assets, debts, and foreseeable earnings.

The Eleventh Circuit held that an untimely IRS claim for taxes under section 507(a)(8) of the Bankruptcy Code in a chapter 7 case should be paid as a priority claim under section 726(a)(1) of the Bankruptcy Code.65 The petition was filed prior to the effective date of the 1994 amendments to the Bankruptcy Code. The court followed the reasoning of In re Pacific Atlantic Trading Co. and In re Vecchio, and distinguished cases decided under chapter 13.

The Fifth Circuit held that a late-filed IRS proof of claim was allowed in a couple’s chapter 13 case but was not entitled to first-tier status with the timely filed proof of claim.66 The district court had previously held that the claim was disallowed. The Fifth Circuit affirmed the district court’s refusal to allow the IRS’s late, amended proof of claim to relate back to the filing of the initial proof of claim.

The Fifth Circuit noted that Bankruptcy Rule 3002(a), establishing the bar date, must be viewed as providing a dividing line between timely and tardy claims, rather than a flat ban on the allowance of late-filed claims. The Fifth Circuit disagreed with the Second Circuit in In re Vecchio, where the Second Circuit viewed “the categorization of late-filed priority claims among other tardily filed allowed unsecured claims as leading to an absurd result.”

A divided Ninth Circuit held that in a chapter 13 proceeding, a proof of claim filed by the IRS after the bar date set under Bankruptcy Rule 3002(c) was properly disallowed.67 The petition was filed prior to the effective date of the Bankruptcy Reform Act of 1994.

The taxpayers filed a joint chapter 13 petition in July 1991, scheduling as priority unsecured debts approximately $25,000 in income and payroll taxes. Their plan, confirmed in October 1991, provided for full payment of these priority claims. The bankruptcy court set December 31, 1991, as a bar date for filing timely proofs of claim. The IRS timely filed a proof of claim in December 1991 for $11,746 for personal income tax. An amended return was filed in April 1992 listing income taxes of $31,000, and in November a second amended claim was filed that for the first time asserted a claim for unpaid payroll taxes. The bankruptcy court allowed the income tax portion of the November 1992 amended claim but disallowed the amendment relating to payroll taxes. The court disallowed the payroll tax claim because it was of a character different from those set forth in the original proof of claim and thus was untimely filed pursuant to Rule 3002(c). The Ninth Circuit Bankruptcy Appellate Panel affirmed.

The Ninth Circuit ruled that the timeliness issue was controlled not by amended section 502(b)(9) of the Bankruptcy Code, as added by the Bankruptcy Reform Act of 1994, but by the rules and authorities governing cases filed before October 23, 1994, specifically, Bankruptcy Rule 3002(c).

The court noted that timeliness is of the essence in claims filed in chapter 13 reorganization and that this case was governed by the strict time requirements on filing claims set forth in In re Tomlan,68 where the Ninth Circuit had held that the law is clear—the bankruptcy court has no discretion to allow a late-filed proof of claim in a chapter 13 case. In reference to In re Pacific Atlantic Trading Co., which might suggest a different rule, the Ninth Circuit concluded that Pacific Atlantic applied only in chapter 7 proceedings.

In describing the difference in the impact between a chapter 7 and 11 case, the Ninth Circuit noted that it is not a matter of allowance or disallowance of claims, because a claim disallowed as a result of late filing can be specially allowed in chapter 7 proceedings prior to distribution of the estate property to the debtor. However, in a chapter 13 case, the court concluded that a chapter 13 debtor retains the assets of the estate in exchange for an agreement to make periodic payments to the creditors that must equal or exceed the amount that the creditors would receive under chapter 7. The debtor thus has an interest only in whatever is ultimately left over, after all claims have been paid. The Ninth Circuit then noted that if late-filed claims are not barred in chapter 13 actions, it would not be possible to determine with finality whether a chapter 13 plan satisfies this standard.

There still remains considerable uncertainty as to the tax impact resulting from a tardy-filed proof of claim, including those in a chapter 11 case. For petitions filed after October 22, 1994, the Bankruptcy Reform Act of 1994 may have helped clarify the issue, dealing with the conflict between the rules and the Bankruptcy Code. Section 502(b) of the Bankruptcy Code was amended to provide that a claim of a governmental unit, including tax claims, will be considered timely if filed before 180 days after the order for relief or such later time as the Federal Rules of Bankruptcy may provide. Section 502 was also amended to provide that a proof of claim not timely filed will not be allowed, except for the governmental claim mentioned above and tardy claims permitted under section 726 of the Bankruptcy Code. The change did not deal with the issue of how to distinguish a tardy proof of claim from an amended proof of claim. The Bankruptcy Reform Act did not address the issue as to the extent to which section 726 of the Bankruptcy Code applies to chapter 11 cases.

However, in In re Larry Merritt Co.,69 the bankruptcy court held that the claim for unpaid prepetition payroll taxes was not entitled to priority because the IRS had received adequate notice and failed to file a timely proof of claim. The IRS filed its proof of claim five months after the bar date. The district court affirmed, citing In re Century Boat Co.,70 where the Sixth Circuit upheld the statutory policy of orderly distribution and settlement of estates as provided for in section 726(a) of the Bankruptcy Code. The district court held that a priority creditor’s untimely claim should be subordinated under 11 U.S.C. section 726(a)(3) if the creditor had notice of the claims bar date and failed to comply with the timing requirements.71

(vii) Burden of Proof

The general bankruptcy rule is that the burden of proof for a claim against a debtor lies with the creditor. Although it may be the responsibility of the debtor to object to a claim and place the issue before the bankruptcy court, the burden of persuasion is on the creditor seeking to enforce the claim.72 The general tax rule is that the burden of proof is upon the taxpayer. Tax Court Rule 142(a) provides that “[t]he burden of proof shall be upon the petitioner, except as otherwise provided by statute or determined by the Court; and except that, in respect of any new matter, increases in deficiency, and affirmative defenses, pleaded in the answer, it shall be upon respondent.” An example of a statutory exception is for fraud, where I.R.C. section 7454 transfers the burden of proof to the IRS by providing that the IRS must prove fraud by clear and convincing evidence.

The Supreme Court73 affirmed a Seventh Circuit case holding that the burden of proof on the tax claim in bankruptcy remained on the petitioner, the trustee of the debtor’s estate. The Supreme Court held that the bankruptcy did not alter the burden imposed by the substantive law and that the bankruptcy estate’s obligation to respondent was established by the state’s tax code. The Court noted that the Bankruptcy Code had no provision for altering the burden on a tax claim, and its silence said no change was intended.

Prior to the Supreme Court decision, there was a conflict among circuits as to who has the burden of proof. The Ninth Circuit held that taxing authorities, like other bankruptcy claimants, bear the ultimate burden of proving their claims. The Ninth Circuit noted that under California law, outside the bankruptcy context, a taxpayer bears the ultimate burden of demonstrating his entitlement to a deduction. Adopting the reasoning of the Fifth and Tenth Circuits,74 the Ninth Circuit held that because tax claims already receive a statutory priority over other creditors’ claims, relieving the Franchise Tax Board of its burden of proof would be granting to the Franchise Tax Board a double benefit not authorized by statute. Quoting In re Wilhelm,75 the Ninth Circuit noted that policy goals of the bankruptcy system are put at risk when one class of creditors is given the benefit of a favorable presumption that has its origins outside bankruptcy law.

The Third, Fourth, and Seventh Circuits76 had applied the general tax rule that places the burden of proof on the taxpayer rather than the tax authority, including the IRS.

Generally, the Eighth Circuit assignment of the burden of proof has varied. However, as noted later, the Eighth Circuit has tended to agree with the courts holding that the general tax rule applies.77

(c) Tax Refund

Section 505(a)(2) of the Bankruptcy Code provides that, before the bankruptcy court can determine the right of the estate to a tax refund, the trustee must file a claim for the refund and either receive a determination from the IRS or allow 120 days to pass after the claim is filed. If the 120-day period expires and the IRS has not made a determination, the bankruptcy court can then determine the right of the estate to a tax refund. Under prior law, the bankruptcy court did not have the right to hear suits for tax refunds. It was necessary for the trustee or debtor to file suit in a district court or the court of claims.78

The Eighth Circuit, reversing the decision of the BAP, held that under section 505(a), the bankruptcy court had jurisdiction to determine the tax liability beyond the years stated in the proof of claim when the liability involved deductions resulting from repayment of embezzled funds.79

The bankruptcy court held that a bankruptcy trustee can recover a debtor’s tax refund under the authority of section 542 of the Bankruptcy Code, even though the trustee had not timely filed a refund claim under section 6511.80 The court ruled that it was not equitably tolling the I.R.C. limitations period in violation of United States v. Brockamp.81

The court acknowledged that a bankruptcy trustee must generally file a refund claim but said that that rule does not apply here due to the specific facts of this case. When the government, the debtor, and the trustee agree on the amount of an overpayment, the court concluded that the claim has been liquidated and the debtor’s interest in the liquidated amount becomes property of the bankruptcy estate. The trustee has no need to commence the refund process under the I.R.C. because the Bankruptcy Code compels the turnover under 11 U.S.C. section 542. Under these facts, the I.R.C. claims process is superseded by bankruptcy law, and thus section 6511 does not apply.

The bankruptcy court82 held that the debtor may not dismiss a case to receive a tax refund. The taxpayer filed a bankruptcy petition and subsequently moved to have it dismissed when he learned that he was entitled to receive a tax refund. The court noted that although individuals have an absolute right to file a bankruptcy petition, they have no absolute right to dismiss it. Generally, most courts allow an individual to move to dismiss his or her case only when cause exists. The court examined whether dismissal would cause the creditors prejudice and found that, although the taxpayer promised to use the tax refunds to pay his creditors, he had no plan to honor his commitment, noting that the taxpayer could spend the refunds and then refile his bankruptcy petition, thus avoiding his creditors. The bankruptcy court refused to dismiss the filing because the taxpayer failed to meet his burden of showing that his creditors would not be prejudiced by the dismissal of his petition.

(d) Determination of Unpaid Tax Liability

The Bankruptcy Code contains a very important provision that requires a governmental unit to determine the tax liability or be prohibited from making assessments of any amount other than that shown on the return. Section 505(b) of the Bankruptcy Code provides that a debtor, or trustee if appointed, may request a determination of any unpaid liability of an estate for any tax incurred during the administration of the case. The request is made by submitting a return for such a tax and a request for determination to the governmental unit charged with responsibility for collection or determination of the tax. Unless such return is fraudulent or contains a material misrepresentation, the trustee, the debtor, and any successor to the debtor are discharged from any liability other than the amount shown on the return. Before the bankruptcy court can determine the tax, a request must be made for the taxing unit to determine the tax.

Section 505(b) is modified by the 2005 Act to provide for the clerk of each district to maintain a listing under which a federal, state, or local governmental unit responsible for collecting taxes within the district may designate an address for service of requests and describe further information concerning additional requirements for filing such requests. If a governmental unit fails to provide an address to the clerk, requests should be served at the address for filing returns or protests with the appropriate taxing authority of that governmental unit. Tax returns and other notices should be filed with the address provided by the clerk in the appropriate district.

The taxpayer is not required to use all administrative remedies before the bankruptcy court can determine the amount of the tax. In In re Piper Aircraft Corp.,83 the bankruptcy court held that the bankruptcy court could determine the amount of the debtor’s tax, even though the debtor did not comply with state administrative procedures. Other bankruptcy courts have also given the bankruptcy court authority to determine the tax without pursuing all available remedies first.84 However, one bankruptcy court subsequently limited the Ledgemere decision to unpaid taxes owed by the debtor and would not extend it to refund claims that had not been previously adjudicated.85

If the return filed has been selected for examination, the taxing unit must notify the debtor of the examination within 60 days after the request for tax determination is made. The taxing unit has 180 days after the request is made to complete the examination. For cause, additional time may be granted by the bankruptcy court. An extension would be expected to be granted for a reasonable time period to allow the taxing unit to complete the audit.

If the taxing unit does not notify the taxpayer within 60 days of the request that an examination will be conducted or if the taxing authority does not complete the examination within the prescribed time, the taxing unit will be prohibited from taking any action to file a claim for any amount other than the amount specified on the return. In In re T. Horace Estes,86 the IRS determined that the trustee had miscalculated the tax due on returns for fiscal years 1984 through 1986 that were filed in October 1986 but did not timely notify the trustee. The court ruled that neither the trustee nor the debtors are personally liable for any taxes, penalties, or interest attributable to the errors made by the trustee, because he had complied with all of the requirements of section 505(b) of the Bankruptcy Code.

In In the matter of Harry Fondiller,87 the district court held in a chapter 7 case that if a claim is timely filed, even though it is not filed within the 60 days after the request was made for the determination of the tax, the claim will be allowed against the estate. The court made a clear distinction between a claim against an estate and a claim against the individual. The court ruled that the estate and the successor to the debtor are two separate entities and are not the same. The court reached this conclusion because section 505(c) of the Bankruptcy Code specifically uses the term “estate” as distinct from a successor to the debtor. Thus, although the IRS may not have a basis to assess the tax against the individual, it can collect the tax from the estate.

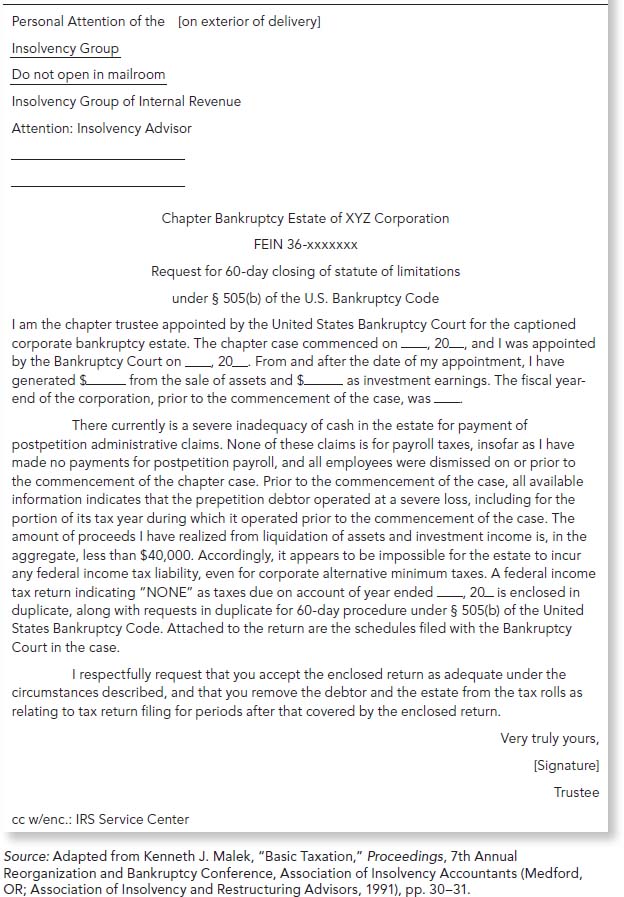

To correct the problem where courts have held that the IRS may assess additional taxes against the estate (but not against the trustee or debtor), section 715 of the 2005 Act amends section 505(b) of the Bankruptcy Code to clarify that the estate is also protected if the government does not make a determination of tax liabilities or request extension of time to audit, then the estate’s liability for unpaid taxes is discharged. In situations where there are no assets in the estate and records are in such a condition that it would involve substantial cost to determine the information to file a tax return, the trustee for the debtor may request that the IRS remove the debtor from the tax rolls. The request may take the form shown in Exhibit 10.1.

On May 30, 2006, the IRS issued Revenue Procedure (Rev. Proc.) 2006-24,88 setting forth steps for a bankruptcy trustee or debtor in possession to follow in obtaining prompt determination by the IRS of any unpaid tax liability of the estate incurred during the administration of the case. During the administration of a bankruptcy estate, the trustee is responsible for filing returns for the estate, and the estate must pay any taxes due. Under Bankruptcy Code section 505(b)(2), the trustee may request determination of the estate’s unpaid liability for taxes incurred during administration of the case by filing a return and request for prompt determination. The Bankruptcy Abuse Protection and Consumer Protection Act of 2005 provides that for cases commenced under the Bankruptcy Code on or after October 17, 2005, the estate, trustee, debtor, and any successor to the debtor will be discharged from any tax liability shown on a return submitted in accordance with Rev. Proc. 2006-24, section 2.01, by payment of the tax:

1. Shown on the return unless (a) within 60 days after the request, the IRS notifies the trustee that the return has been selected for examination, and (b) within 180 days after the request (or additional time as permitted by the court), the IRS completes the examination and notifies the trustee of any tax due;

2. As finally determined by the bankruptcy court; OR

3. As finally determined by the IRS.

The trustee must file the signed written request with the IRS’s Centralized Insolvency Operation together with an exact copy of the return according to detailed procedural guidelines set forth in Rev. Proc. 2006-24.

EXHIBIT 10.1 Notice of Lack of Funds and Request for Removal from Tax Rolls Sample

Rev. Proc. 2006-24 provides that:

To request a prompt determination of any unpaid tax liability of the estate, the trustee must file a signed written request, in duplicate, with the Centralized Insolvency Operation,[89] Post Office Box 7346, Philadelphia, PA 19101-7346 (marked, “Request for Prompt Determination”). To be effective, the request must be filed with an exact copy of the return (or returns) for a completed taxable period filed by the trustee with the Service and must contain the following information:

(1) A statement indicating that it is a request for prompt determination of tax liability and specifying the return type and tax period for each return for which the request is being filed;

(2) The name and location of the office where the return was filed;

(3) The name of the debtor;

(4) The debtor’s Social Security number, taxpayer identification number (TIN) and/or entity identification number (EIN);

(5) The type of bankruptcy estate;

(6) The bankruptcy case number; and

(7) The court where the bankruptcy is pending.

Once the information, referred to as a request package, is received by the Centralized Insolvency Operation, the request must be assigned to a field insolvency office. (Practice indicates that the request package is sent to an insolvency group manager in the appropriate field office and assigned to an “insolvency advisor” in the group.)

A copy of the return(s) submitted in the request package must be an exact copy of a valid return. Rev. Proc. 2006-24 provides that a request will be considered incomplete and returned to the trustee if it is filed with a copy of a document that does not qualify as a valid return. A document that does not qualify as a valid return includes a return form filed by the trustee with the jurat stricken, deleted, or modified. A return must be signed under penalties of perjury to qualify as a return. See Rev. Rul. 2005-59, 2005-37 I.R.B. 505 (Sept. 12, 2005).

Rev. Proc. 2006-24 provides that if the request is incomplete, all of the documents received will be returned to the trustee by the field insolvency office assigned the request with an explanation identifying the missing item(s) and asking that the request be refiled once corrected. An incomplete request includes one submitted with a copy of a return form, the original of which does not qualify as a valid return. Once corrected, the request must be filed with the IRS at the field insolvency address specified in the correspondence returning the incomplete request. In the case of an incomplete request submitted with a copy of an invalid return document, the trustee must file a valid original return with the appropriate IRS office and submit a copy of that return with the corrected request when the request is refiled.

It is important for the taxpayer to realize that the 60-day period for notifying the trustee whether the return filed by the trustee is being selected for examination or is being accepted as filed does not begin to run until a complete request package is received by the IRS. If a request package is returned by the field insolvency office, the request package must be returned to the field insolvency office specified by the IRS in the correspondence included with the return of the incomplete request package with the additional information requested.

In requesting the determination of a tax ending after the petition date for an individual, where a 1040 is attached to an estate return, a note stating “Do Not Open in Mailroom” should be included on the envelope.

A discharge of any additional liability will be granted on payment of the tax stipulated in the return if:

- The taxing unit accepts the return as filed by not notifying the debtor that the return will be examined.

- The taxing unit conducts an examination and determines that additional taxes are due, and the debtor accepts the taxing unit’s examination results and pays the additional tax.

- The taxing unit conducts an examination and determines that additional taxes are due; the bankruptcy court determines, after proper notice and hearing, that the additional taxes are proper; and the debtor pays the additional taxes due.

- The taxing unit does not complete the examination and notify the debtor of an additional tax due within 180 days, including extensions granted by the bankruptcy court, after the request was filed.90

A discharge will not be granted if the tax return submitted is fraudulent or contains a material misrepresentation.91

After the taxpayer in George Louis Carapella v. United States92 was discharged from bankruptcy, the government contended that the taxpayer remained liable for the taxes because fraudulent returns were filed and attempts were made to evade tax liability for three years. The court agreed with the IRS, which claimed that the tax liability falls within the exception to discharge under 11 U.S.C. section 523(a)(1). In La Difference Restaurant, Inc.,93 the court held that the IRS was enjoined from seeking to collect taxes, penalties, and interest allegedly owed by the debtor on the ground of equitable estoppel. This deficiency, which the IRS was unable to collect, related to the difference between the original proof of claim and the amount based on an agreement the debtor had made with the IRS and had then used in developing a plan that was subsequently confirmed. This ruling was made by the court even though a clause in the plan provided that, if additional taxes have not been claimed prior to confirmation and are determined to be due, they will be paid immediately.

If a taxpayer petitions the court to determine a tax liability under section 505 of the Bankruptcy Code, it is important that the IRS be properly served. Rule 7004(b)(4) of the Federal Rules of Bankruptcy Procedure provides that, in the case of an adversary proceeding, a copy of the summons and complaint must be sent to the U.S. Attorney for the district in which the action is brought and to the U.S. Attorney General at Washington, DC. In any action attacking the validity of an order of an officer or agency of the United States not made a party, a copy of the summons and complaint must also be mailed to the officer or agency.

In In re Johnny Ray Warren,94 the bankruptcy court ordered the taxpayer’s case reopened because the court had lacked personal jurisdiction over the government at the time it had entered a previous order. Warren filed for bankruptcy and petitioned the court to have his tax liability determined. Notice was served on the IRS Special Procedures Staff95 and on the U.S. Attorney in Dallas. Notice was not served on the Attorney General of the United States, as required by Bankruptcy Rule 7004(b)(4). The bankruptcy court entered default judgment and held Warren not liable for the penalty under I.R.C. section 6672.