§ 11.3 TAX DISCHARGE

(a) Introduction

The extent to which a tax is discharged depends on (1) whether the debtor is an individual or a corporation, (2) the chapter under which the petition is filed, and (3) the nature and priority of the tax.

The dischargeability of tax fines and penalties and interest depends on the nature of the tax to which penalties and interest relate. If the tax is nondischargeable, interest and penalties will not be discharged.250 The converse is also true. The bankruptcy court has original, but not exclusive, jurisdiction to determine the dischargeability of tax claims.251

(b) Individual Debtors

Section 523(a) of the Bankruptcy Code provides that in a chapter 7 or chapter 11 proceeding involving an individual debt, all taxes that are entitled to priority are exempt from a discharge. Also exempt from discharge are prepetition taxes due for a period when the debtor failed to file a return, filed the return late and it was filed less than two years before the petition date, or filed a fraudulent return or willfully attempted in any manner to evade or defeat the tax due. When fraud is involved, the court may hold that the tax claim is nondischargeable.252 Any tax due that relates to failure to file a return or to other misconduct of the debtor will be considered nondischargeable if such tax qualifies for priority under Bankruptcy Code section 507. Some question exists as to whether a return filed late due to a reasonable cause would be considered nondischargeable. Section 523(a)(3) of the Bankruptcy Code provides that a claim that is not listed nor scheduled in time to permit the filing of a proof of claim will not be discharged unless the debtor had notice or actual knowledge of the case in time to file the proof of claim. A tax return filed by the IRS does not satisfy the return requirements for determining dischargeability of taxes. In Robert G. Gushue,253 in 1982, the IRS filed substitute returns on behalf of the taxpayer, for 1975 to 1978. The taxpayer contested the determination of the taxes in Tax Court and then later settled with the IRS. The taxpayer subsequently filed a bankruptcy petition. The bankruptcy court held that the tax liabilities for 1975 through 1978 were not dischargeable because Gushue failed to file returns. The court rejected the taxpayer’s argument that the substitute returns filed by the IRS were returns for the purposes of I.R.C. section 6020(a) and section 525 of the Bankruptcy Code dealing with taxes that are nondischargeable.

Section 523(a) of the Bankruptcy Code provides that a tax that has priority in a chapter 7 and 11 case may not be discharged. In In re Doerge,254 the debtor did not raise the statute of limitations defense in his tax court petition. Under Tax Court Rule 34(b)(4), the court noted “the failure to include this contention of error in his petition constituted a waiver for purposes of the tax court litigation.”255 The court noted that because the debtor did not raise this defense, it appears that he intended to waive the issue of expiration of the statute of limitations and, therefore, foreclose it from further litigation.

Based on the fact that the taxpayer failed to raise the issue of statute of limitations and that the debtor’s 1981 taxes contained a stipulation in which the debtor agreed to waive the statutory restrictions that prohibited assessment and collection of the tax deficiency until the decision had become final, the court concludes that the equitable doctrine of estoppel precludes the debtor from changing his position in this action to defeat the government’s claim of nondischargeability of the 1981 taxes. Thus the court concluded that the debtor’s 1981 tax liability was still assessable at the time of the filing of the bankruptcy petition and is thus nondischargeable as a priority tax under section 523(a)(1)(A) and section 507(a)(8)(A)(iii) of the Bankruptcy Code.

In a footnote, the court noted that in Levinson v. United States,256 the Seventh Circuit set forth certain boundaries on the applicability of judicial estoppel: The litigant’s later position must be clearly inconsistent with his earlier position, the facts at issue must be the same in both cases, and the party to be estopped must have been successful in convincing the court of his position in the earlier proceeding. The court noted that the “last requirement is not technically met in this case even though the court’s decision incorporated the debtor’s stipulation agreeing to immediate assessment, because the debtor could not have convinced the court of a position he did not raise.”

The district court held that postpetition interest accruing on a secured IRS claim for employment taxes is not exempt from discharge under Bankruptcy Code section 507(a)(8). The taxpayers commenced separate chapter 11 proceedings, and the IRS filed secured claims in each case.257

The court distinguished Carapella v. United States258 and Rev. Rul. 74-203 because the taxpayer never executed a Form 870 and did not sign the substitute returns.

(i) Failure to File Tax Returns

In order for an individual to be discharged from a tax, a tax return must have been filed, according to section 523(a)(1)(B) of the Bankruptcy Code. One of the first issues that commonly arise when the IRS files a substitute return for the taxpayer is whether a substitute return qualifies as a tax return. The 2005 Act amends section 523(a)(1)(B) by providing a definition of a tax return for purposes of dischargeability that includes a return prepared under section 6020(a) of the I.R.C. or similar nonfederal statutes and does not include a return prepared under section 6020(b) as described earlier. In Douglas W. Bergstrom v. United States,259 the Tenth Circuit held that substitute returns filed under I.R.C. section 6020(a) are not filed returns for purposes of discharge of tax requirements.

The bankruptcy court held, in John Arenson v. United States,260 that the tax claims from amended returns filed to challenge the IRS’s determination of tax liability are not tax returns for purpose of determining the dischargeability of taxes under section 523(a)(1)(B)(1) of the Bankruptcy Code. The court noted that the taxpayer’s failure to file returns precluded discharge and that the amended returns were filed only after the IRS had determined Arenson’s tax liability and for the purpose of challenging the IRS’s determination of the tax.

Tax returns filed by tax protesters are not considered tax returns for purposes of section 523(a)(1)(B) of the Bankruptcy Code. The tax is not dischargeable even though the return was filed more than two years prior to bankruptcy and the tax return was due more than three years prior to bankruptcy.261

In In re Gushue,262 the bankruptcy court ruled that a stipulated settlement executed by the debtor in Tax Court did not satisfy the requirements for a return because the debtor had been uncooperative with the IRS.

In In re Carapella,263 the court ruled that a Form 870 waiver of restrictions on assessment, executed by the debtor in cooperation with the IRS, satisfied the requirements of section 523(a)(1)(B)(i) of the Bankruptcy Code. In In re Lowrie,264 the bankruptcy court distinguished this case from most others because the taxpayer was cooperative: She signed a form containing sufficient information to calculate her tax liability, and she admitted owing the taxes.

Several courts have examined the issue of the extent to which a return filed after the taxes were assessed should be considered a “return” under section 523 of the Bankruptcy Code. Several of the recent cases are examined here.

The Sixth Circuit reversed a district court decision granting a debtor summary judgment on the dischargeability of taxes, holding that the debtor’s Forms 1040, filed after the IRS prepared substitute returns and made assessments, were not “returns” under 11 U.S.C. section 523(a)(1)(B).265 In 1990, the IRS prepared substitute returns and issued deficiency notices because the taxpayer failed to timely file his 1985 to 1988 income tax returns. After the IRS assessed taxes based on the substitute returns in 1993, the taxpayer filed income tax returns that were substantially the same as the substitute returns.

The Sixth Circuit held that a tax return filed after a deficiency assessment no longer qualifies as a “return” under section 523(a)(1)(B). The circuit court noted that in order for a document to qualify as a return: “(1) it must purport to be a return; (2) it must be executed under penalty of perjury; (3) it must contain sufficient data to allow calculation of tax; and (4) it must represent an honest and reasonable attempt to satisfy the requirements of the tax law.”266 This test was derived from two Supreme Court cases.

The Sixth Circuit concluded that a Form 1040 filed too late is not a return because it ceases to serve any tax purpose and has no effect under the I.R.C. A purported return that has no effect under the code cannot constitute an honest and reasonable attempt to satisfy the requirements of the tax law, which is the fourth requirement of Beard v. Commissioner. The Sixth Circuit concluded that if a document purporting to be a tax return serves no purpose at all under the I.R.C., such a document cannot, as a matter of law, qualify as an honest and reasonable attempt to satisfy the requirements of the tax law. Accordingly, the document was held not be a “return” for purposes of section 523(a)(1)(B) of the Bankruptcy Code.

The Sixth Circuit acknowledged that it did not address the issue of a “return” if the return showed additional tax. However, in a footnote, the Sixth Circuit stated: “We do not conclude that were Hindenlang able to show a tax purpose for filing a Form 1040 after the IRS has made an assessment, he would automatically satisfy the fourth prong of the Beard test. The government could still produce particularized evidence showing that such a late filing of a Form 1040 was neither an honest nor reasonable attempt to comply with the tax law. We save resolution of that hypothetical case for another day.”

Section 6020(b) of the I.R.C. gives authority to the IRS to prepare a return from its own knowledge and from other information that can be obtained through testimony or otherwise if the taxpayer fails to file a return or files a false or fraudulent return. The legal memorandum concluded that taxes derived from a Substitute for Return (SFR) covered under section 6020(b) would be treated as excepted from discharge under Bankruptcy Code section 523(a)(1)(B).

In a bankruptcy case,267 the IRS issued a Notice of Deficiency and, receiving no response, prepared substitute returns for debtor. After seizures of property, debtor “voluntarily” came in and completed tax returns. In a subsequent bankruptcy proceeding, the debtor argued that his taxes were dischargeable under the “plain meaning” of Bankruptcy Code section 523(a)(1)(B)(i), since he did in fact file returns. The bankruptcy court disagreed, finding the debtor’s “plain meaning” led to an absurd result. Once an involuntary government-made assessment is final, the court said, the taxpayer’s belated filing of a return serves no revenue purpose. Therefore, under section 523(a)(1)(B)(i), the debtor forfeits his right to discharge the taxes in bankruptcy.

A bankruptcy court held that a debtor filed returns when he filed Forms 1040 after the IRS made assessments, and thus his taxes were dischargeable under 11 U.S.C. section 523(a)(1)(B).268 However, the court ruled that the taxes were nondischargeable under section 523(a)(1)(C) because the debtor had attempted to evade the taxes. The court rejected the IRS’s first argument that Forms 1040 filed after assessments are made do not constitute returns for purposes of section 523(a)(1)(B). Note the bankruptcy court decision in Hindenlang v. United States, which held that forms filed by the debtor after assessment constituted returns, based on the plain language of section 523(a)(1)(B). However, as noted earlier, the Sixth Circuit reversed both the bankruptcy court and district court’s decision in Hindenlang. That statute, the Hindenlang court concluded, creates a bright-line rule, which says that if the debtor’s return was filed less than two years prepetition, the associated taxes are nondischargeable.

Citing Germantown Trust Co. v. Commissioner,269 which established the criteria for a proper return, the bankruptcy court found that the IRS did not dispute that the taxpayer filed the returns, that the returns were executed and sworn to by the taxpayer, that they contained sufficient data to calculate his tax, and that they were not facially irregular or fraudulent. The bankruptcy court determined the position taken by the IRS (that a return could not be considered a return if filed after the tax was assessed) to be meritless, because the IRS’s position would result in the court placing a significant additional requirement on the taxpayer to avoid nondischargeability filing a return prior to assessment. The court noted that Congress chose not to place significance on the time of assessment and that section 523(a)(1)(B)(ii) of the Bankruptcy Code creates a bright-line rule which says that if the debtor’s return was filed less than two years prepetition, the associated taxes are nondischargeable.

Other courts have also dealt with the extent to which a return can be considered filed, if filed after the tax is assessed. In In re Sullivan,270 the bankruptcy court held that a debtor’s 1981 to 1984 taxes were dischargeable even though tax returns were filed after the IRS issued a deficiency notice, because the returns were filed before the IRS assessed the taxes and more than two years before the debtor filed for bankruptcy.

In In re Olson,271 the bankruptcy court held that the state tax liabilities, penalties, and interest for the years 1978 to 1981 were dischargeable because the debts were not excepted from discharge under section 523(a)(1)(B)(i) of the Bankruptcy Code. The court noted, however, that the state tax debts would have been excepted from discharge if the Olsons had been required to file amended returns for these years. Because the State of North Dakota had notified the taxpayer that amended returns were not required for 1978 to 1981, the tax claims could be discharged.

The district court held that a return must be signed before it is considered filed, reversing a decision by the bankruptcy court holding that an unsigned return was considered a return for tax discharge purposes.272 The district court noted that both the Tax Court and the federal courts of appeal have consistently held that an unsigned tax return is no return at all, because an unsigned tax return would be insufficient to support a perjury charge based on a false return. Thus, the unsigned return was not deemed filed until the IRS received the signed verification statement, which was within two years before the bankruptcy petition was filed, with the result that the tax was not discharged under the provisions of section 523(a)(1)(B)(ii) of the Bankruptcy Code. The original unsigned return was filed more than two years before the bankruptcy petition was filed.

A U.S. bankruptcy court held that a bookmaker’s taxes for wagering are nondischargeable.273 The taxpayer argued that his wagering taxes are dischargeable in bankruptcy because he was unaware that a return should be filed. As a result of this lack of knowledge, his debt should be discharged under section 523(a)(1)(C) of the Bankruptcy Code because his failure to file wagering tax returns was excusable, and not willful. The bankruptcy court concluded that although lack of knowledge would be a valid defense in a criminal proceeding, where willfulness is a necessary element of proof, it is irrelevant to the issue of dischargeability under section 523(a)(1)(B)(i) of the Bankruptcy Code. The bankruptcy court explained that because the taxpayer did not file the required tax returns, the taxes at issue were not dischargeable.

(ii) Delinquent Returns

As a general rule, an amended return is not considered a tax return. For example, in In re Arenson,274 the district court agreed with the bankruptcy court that an amended return in response to a substitute return filed by the IRS for the taxpayer is not a return for purposes of section 523(a)(1)(B)(i). The bankruptcy court relied on the Supreme Court’s decision in Badaracco v. Commissioner.275 See § 11.3(b)(iii).

Late tax returns that are filed within two years prior to the filing of a bankruptcy petition are nondischargeable according to section 523(a)(1)(B) of the Bankruptcy Code. This requirement is in addition to the three requirements set forth in section 507(a)(8)(A) of the Bankruptcy Code. Taxes due on late tax returns that were filed more than two years prior to the filing of the petition and more than three years prior to the original due date of the return, but still assessable because of the three-year statute of limitations assessment, are still not dischargeable. The court in In re Torrente276 supported the concept that sections 523(a)(1)(B)(ii) and 507(a)(8)(A)(iii) of the Bankruptcy Code work together and expand the concept of dischargeability of the tax. However, the bankruptcy court in In re Doss,277 in a very technical interpretation, held that section 507(a)(8)(A)(iii) was inapplicable because the late return was filed more than two years before the bankruptcy petition was filed. Thus, a tax that would not otherwise have been dischargeable was considered dischargeable because the taxpayer filed the federal tax return late.

In In re Smith,278 the court held that a tax related to a late return filed more than two years before the bankruptcy petition was filed was not dischargeable under section 507(a)(8)(A)(i) of the Bankruptcy Code, because the due date of the tax return was less than three years before the bankruptcy petition was filed.

In many states, the state income or franchise tax is based on the adjusted gross income reported on the federal return. If an adjustment has been made in the federal return, an amended state tax return must be filed in a relatively short time period, such as 20 days. If the state tax return is not filed, it may be considered late and thus the tax may be nondischargeable under section 523(a)(1)(B)(i) of the Bankruptcy Code. The amount that is nondischargeable may be the total amount of the tax for the year, not just the additional state tax resulting from a federal tax adjustment.

When a taxpayer’s federal tax liability is changed due to an audit, states that have an income tax require the taxpayer to report a change in federal income tax to the state. The method of making the report and the time of the report will vary among the states requiring the report. A majority of the states with an income tax require the taxpayer to file an amended return with the state and attach a copy of the revenue agent’s report. Other states allow the debtor to file an amended return, provide the state with a copy of the revenue agent’s report, or file a form to report the change resulting from the audit.

In states that require an amended return, courts have generally held that the amended return is not a return for purposes of section 523(a)(1)(B). However, a few courts have held that the amended return was a return and thus a tax that otherwise would have been discharged is no longer discharged if the bankruptcy petition was filed within two years after the amended return was filed.279

For those states that require a report—such as a special form or a copy of revenue agent’s report—the courts have generally held that the filing of these reports do not constitute a return.280 However, in In re Blutter,281 the bankruptcy court held that a report was a required return.

In determining whether the petition was filed after the two-year period lapsed, careful consideration must be given to the exact date that action was taken. For a late return, the date of filing is based on the “physical delivery rule,” which holds that documents are deemed “filed” when “delivered and received” by the IRS.282

There is a statutory exception to the physical delivery rule under I.R.C. section 7502, referred to as the “timely mailing is timely filing” exception. I.R.C. section 7502 provides that if a return is mailed on or before its prescribed due date, the date of delivery will be deemed to be the last date of the postmark on the cover in which such return is mailed. However, in cases where the tax return is late this exception is inapplicable.283

In In re Smith, the debtor filed his bankruptcy petition on Saturday, November 23, 1993. On Thursday, November 21, 1991, the debtor executed his tax returns for 1987 to 1989 and forwarded them to the IRS on Friday, November 22, 1991, via Federal Express. The returns were stamped received by the IRS on November 25, 1991. The court concluded that as the returns were not filed until November 25, 1991, they were filed within the two-year window before the date of the filing of the petition. The taxes for those years were therefore not dischargeable.

Another factor to consider is the date that the petition is filed. If a petition is filed on a Saturday or Sunday, Monday should be considered as the date the petition is filed. Federal Rules of Bankruptcy Procedure (Fed. R. Bankr. P.) 9006 states, in relevant part:

(A) Computation. In computing any period of time prescribed or allowed by . . . any applicable statute, the day of the . . . event, . . . from which the designated period of time begins to run shall not be included. The last day of the period so computed shall be included, unless it is a Saturday, a Sunday, . . . in which event the period runs until the end of the next day which is not on the aforementioned days.

In In re Smith, bankruptcy court held that “the date which falls ‘two years before the date of the filing of the petition’ under section 523(a)(1)(B)(ii) does not represent a filing deadline which can be expanded by Fed. R. Bankr. P. 9006(A).” The Sixth Circuit in In re Butcher284 rejected a similar claim and held that under a Bankruptcy Code provision requiring action to avoid preferential or fraudulent treatment to be commenced within two years after appointment of the trustee, the two-year period begins to run as of the date of the trustee’s appointment, rather than the day after the trustee’s appointment, and expires 24 months later, irrespective of whether the last day falls on a Saturday, Sunday, or legal holiday.

The date that the return is filed is strictly enforced. For example, for untimely filed income tax returns, the filing date is the date received by the IRS.285 The district court held that a couple was not entitled to a refund because the return was received by the IRS two days late. The district court noted that for untimely filed income tax returns, the tax return is considered received on the actual date received by the IRS and not the date mailed.

While acknowledging that this decision was unfortunate, the district court noted that the Sixth Circuit is consistent in denying equitable pleas to disregard the strict timing rules of the I.R.C. and the Bankruptcy Code.286

(iii) Fraudulent Returns or Attempts to Evade or Defeat the Tax

These taxes are never dischargeable under section 523(a)(1)(B) of the Bankruptcy Code. The Supreme Court held, in Grogan v. Garner,287 that the proof for the dischargeability exception (section 523) is the ordinary “preponderance of the evidence” standard. Phelan and Bezozo note that this is

contrary to the standard of proof applied by the bankruptcy court when determining the amount of legality of any tax, or penalty relating to a tax, under section 505(a). Because of the different standards that may be applied to the IRS’s assertion of fraud in connection with a tax claim, it is possible that the bankruptcy court could find that the taxes are not fraudulent for purposes of asserting a civil tax penalty, but that the taxes are fraudulent for purposes of determining their dischargeability.288

A question arises as to the extent that the nondischargeability of the tax would apply in the case where the first return was fraudulent but the taxpayer subsequently filed a nonfraudulent tax return. In Badaracco v. Commissioner,289 the Supreme Court held that the second filing did not remove the statute of limitations that applies to fraudulent returns. It would appear that the same rule would apply to dischargeability of taxes under section 523 of the Bankruptcy Code and the taxpayer would not be discharged from the tax.

In Ronald Eugene Nye v. United States,290 the district court determined that tax liabilities associated with a fraudulent return due more than three years before the bankruptcy petition was filed were not dischargeable. The court also held that the issue of fraud was barred by the doctrine of res judicata. The IRS had determined deficiencies and fraud penalties against the taxpayer for tax years 1980 and 1981. The determination was challenged in the Tax Court and that case ended in a stipulated decision under which Nye agreed to pay the additional taxes, interest, and a 5 percent fraud penalty. Later a chapter 13 petition was filed.

The court held that the fraud penalties were dischargeable under section 523(a)(7)(B) of the Bankruptcy Code because the penalties arose from a transaction occurring prior to three years before the filing of the bankruptcy petition.

In Creigh A. Bogart v. United States,291 the bankruptcy court ruled that the failure to file estimated returns and to pay tax liability out of proceeds from the sale of a partnership interest was not fraud. The court held that the IRS failed to show by a preponderance of the evidence that Bogart willfully intended to evade the tax. The court noted that “[s]imply failing to pay a tax liability is not tantamount to fraud or an attempt to defeat or evade the tax.”

As a general rule, courts have held that taxes assessed against those that attempt to evade taxes, including tax protesters, are not dischargeable. The Fifth Circuit held that tax assessments against a couple were not dischargeable in bankruptcy because the couple had willfully evaded their tax liabilities.292 The Fifth Circuit concurred with the lower courts’ conclusions that the taxpayers’ conduct indicated fraud, and rejected all of the arguments made by the taxpayers as meritless.

In the case of Macks v. Clinton,293 the district court concluded that Kenneth Macks’s tax liability was previously determined in a Tax Court proceeding. The IRS sought to collect from Harvey Macks the unpaid tax liabilities of his brother, Kenneth Macks, based on an alleged fraudulent conveyance of Kenneth Macks’s real property to Harvey Macks.

Kenneth Macks asserted that the tax liabilities were discharged in his bankruptcy case, but the district court granted the government’s motion to amend the summary judgment to provide that Kenneth Macks owed the taxes. The district court noted that a bankruptcy discharge does not affect unpaid tax liabilities where there has been a fraudulent conveyance.

The district court ordered that judgment be entered declaring that Kenneth Macks was the owner of the real property and that Harvey Macks had no interest therein. The court then held that the IRS had valid tax liens encumbering the real property but subject to a previously recorded bank’s lien on one of the two parcels of real property.

The district court concluded that the government had proved that fraudulent conveyance had occurred because Kenneth Macks had intended to defraud the government. No consideration was ever paid for the purported property transfers.

In In re Angel,294 the bankruptcy court held that Steven M. Angel’s tax liabilities were excepted from discharge under section 523(a)(1)(C) of the Bankruptcy Code because Angel’s action went beyond a mere failure to pay. Although he owed over $200,000 in tax debts, Angel purchased several luxury motor vehicles, paid $225,000 for the construction of a home, and then filed for bankruptcy. The court noted that because Angel had a present ability to pay his taxes and instead bought items for his own enjoyment, the court would not be party to such tax-evasive actions.

In In re Smith,295 the bankruptcy court concluded that the filing of false W-4s overstating exemptions is insufficient, standing alone, to constitute a willful attempt to evade or defeat a tax liability. David Wayne Smith filed for a bankruptcy petition on April 19, 1993, and claimed that his outstanding personal income taxes were dischargeable because they were due more than three years prior to the bankruptcy filing. The government argued that Smith’s taxes were nondischargeable under section 523(a)(1)(C) of the Bankruptcy Code because he filed fraudulent returns or willfully attempted to evade tax by submitting false W-4s that resulted in underwithholdings.

In reaching the conclusion that the filing of the false W-4s was not considered fraudulent, the court noted that Smith submitted reasonably accurate and timely tax returns for each of the taxable years at issue and professed a good-faith intention to pay his tax liability. According to the district court, the bankruptcy court applied the wrong legal standard: “Willful connotes an act done with a bad purpose or with an evil motive.” The district court’s position was that “willful” in this context requires only a voluntary, conscious, and intentional violation of a known legal duty. The Bankruptcy Court therefore erroneously granted the debtor a discharge.296

In Toti v. United States,297 the Sixth Circuit determined that an attempt to evade a tax can result in the tax’s not being discharged under section 523(a)(1)(C) of the Bankruptcy Code. The Sixth Circuit held that the government needs to prove specific criminal intent in order to invoke the evasion exception to discharge.

As noted, section 523(a)(1)(C) of the Bankruptcy Code provides that when the taxpayer has willfully attempted to evade his taxes, they may not be discharged. The decision in Toti suggests that, in most cases, it will be extremely difficult for taxpayers to claim there was no willful attempt on their part to evade taxes.

Robert G . Nath noted, in describing the interesting aspect of this case, that the “remarkable affirmance is of the factual finding of evasion.”298 The court noted that Toti had failed to file his obligations. Because the failure was with knowledge of the duty to file and was voluntary, conscious, and intentional, the court held that Toti had evaded his taxes and as a result could not get a discharge.

In In re Bruner,299 the Fifth Circuit, affirming both the district court and bankruptcy court decisions, held that a couple’s tax liabilities were not dischargeable in bankruptcy, because they had willfully attempted to evade or defeat their tax obligations. The Bruners filed a joint income tax return for 1980 but failed to file returns for the next eight years. In 1988, the husband, a surgeon, pleaded guilty to willfully failing to file his 1981 tax return. The district court ordered him to pay a $10,000 fine, pay his tax liabilities for 1981, and file returns for 1981 to 1988. The IRS created substitute returns for some of those years, and the Bruners filed the other returns. Based on these returns, the IRS determined a $290,000 deficiency against the couple for 1981 to 1988. The Bruners made payments on the debt between 1989 and 1993. In 1993, the Bruners filed chapter 7 bankruptcy petition and asked the bankruptcy court to determine the tax. The IRS filed a proof of claim for over $365,000. The bankruptcy court held that the Bruners’ tax liabilities for 1981, 1983, 1986, 1987, and 1988 were not dischargeable, pursuant to section 523(a)(1)(C) of the Bankruptcy Code, because the Bruners had willfully attempted to evade or defeat their taxes for those years. The district court affirmed.

The Fifth Circuit affirmed the decision of both the bankruptcy court and district, noting that the Bruners had voluntarily and intentionally violated their duty to pay taxes. The court noted that the couple had filed a 1980 tax return, indicating that they knew of their duty. Also, large cash transactions made by the Bruners and their concession that Three-L Ministries was a shell entity for hiding income and assets were indication of their intent to evade taxes.

The Fifth Circuit noted that in In re Toti, the Sixth Circuit held that section 523(a)(1)(C) “includes acts of commission and acts of omission.” The Fifth Circuit noted that the Bruners had committed both. The Fifth Circuit noted that this approach was preferable to the position taken by the Eleventh Circuit in In re Haas,300 which held that a man who had filed his tax returns but had not remitted payment was entitled to have his tax debts discharged in bankruptcy, because he was an honest debtor. The Haas court noted that the tax code imposes a heavier criminal liability on those who willfully attempt to evade their taxes than it does on those who simply fail to pay, and reasoned that section 523(a)(1)(C) of the Bankruptcy Code should follow the usage of the I.R.C. The Eleventh Circuit concluded that the debtor’s allocation of assets to liabilities other than taxes, even though the debtor is aware of the taxes due and owing, does not constitute willful evasion.

Disagreeing with the Eleventh Circuit’s position, the Fifth Circuit was not convinced that the language of the I.R.C. must be interpreted the same as that of the Bankruptcy Code. The court concluded by pointing out that the Bruners was not a case of mere nonpayment but involved much more flagrant conduct aimed at avoiding even the imposition of a tax assessment against them. A district court affirmed a bankruptcy court’s decision that held that a couple was entitled to a discharge of the tax liabilities they had failed to pay with respect to disallowed tax shelter losses. Relying on In re Haas, the district court agreed with the bankruptcy court that the evidence established only that the taxpayers failed to pay their taxes.301

Section 523(a)(1)(C) of the Bankruptcy Code provides that any tax with respect to which the debtor made a fraudulent return or willfully attempted in any manner to evade or defeat such tax is not dischargeable. Based on this section of the Code, the Tenth Circuit has held nondischargeable a tax debt for which the debtor’s only attempt to evade or defeat tax was his concealment of assets out of which the tax debt might be satisfied.302 The court relied on opinions from the Fifth and Sixth Circuits and from bankruptcy courts in other jurisdictions to construe the phrase “in any manner” in section 523(a)(1)(C) as “sufficiently broad to include willful attempts to evade taxes by concealing assets to protect them from execution or attachment.” 303

The Tenth Circuit noted that while nonpayment, by itself, does not compel a finding that the given tax debt is nondischargeable, it is relevant evidence that a court should consider in the totality of conduct to determine whether or not the debtor willfully attempted to evade or defeat taxes. Both the bankruptcy court and the district court concluded that Dalton’s tax debts were nondischargeable.

The Eleventh Circuit, reluctantly reversing the bankruptcy and district courts, has held that a debtor’s efforts to evade payment, not assessment, was not a willful attempt to evade or defeat such tax under section 523(a)(1)(C) of the Bankruptcy Code.304 The Eleventh Circuit subsequently voted for a rehearing en banc and vacated the panel’s decision.305 In a subsequent rehearing, the taxes were held not to be discharged.306

An IRS audit revealed that Leroy Charles Griffith substantially underpaid his taxes for the years 1969 to 1970, 1972 to 1976, and 1978. Less than a month after the Tax Court issued its decision, on October 10, 1988, NuWave, Inc. was incorporated, with Griffith’s long-time live-in girlfriend, Linda, as sole shareholder. On June 8, 1989, Linda and Griffith married, and Griffith signed an antenuptial agreement in which he transferred stock in two of the corporations, $390,000 in promissory notes, and other assets to NuWave, Inc. The transfers occurred the same day Griffith got married. The IRS made an assessment against Griffith on September 28, 1989. However, the assets transferred pursuant to the antenuptial agreement were insulated from being levied upon because assets held by tenants in the entirety cannot be levied upon without a judgment against both owners. Griffith no longer had any ownership interest in those assets transferred to NuWave, Inc.

The bankruptcy court determined that Griffith attempted to evade the payment of $2 million in tax debt and, as a result, the taxes were nondischargeable under section 523(a)(1)(C) of the Bankruptcy Code. After the bankruptcy court’s decision, the Eleventh Circuit decided, in In re Haas, that the taxes were dischargeable. Haas filed accurate tax returns but had not paid the taxes due; instead, he used his income to pay business and personal debts. The Eleventh Circuit concluded that Haas’s conduct did not amount to an attempt to willfully evade or defeat taxes at the assessment stage, which would have precluded a discharge. In Griffith’s case, the district court affirmed the lower court’s denial of a discharge because Griffith had engaged in a fraudulent transfer of assets to prevent the collection of his taxes. The district court distinguished Haas, stating that, unlike Haas, Griffith had engaged in dubious transfers of assets.

In Hass, upon filing for bankruptcy, the taxpayer sought discharge of the tax debts, which the government opposed on the basis of section 523(a)(1)(C). The Haas panel found that a literal reading of the statute, including the broad phrase “in any manner,” would conflict with the goals of bankruptcy—to provide an opportunity for a fresh start. The panel noted that the language (“willfully attempting in any manner to evade or defeat any tax”) in section 523(a)(1)(C) of the Bankruptcy Code is identical to the wording (“willfully attempting in any manner to evade or defeat any tax or the payment thereof”) in section 6531(2) except that “or the payment thereof” is not in the Bankruptcy Code. The panel relied on the absence of the phrase “or the payment thereof” from section 523(a)(1)(C) to conclude that the provision precludes discharge when the debtor willfully attempted to evade or defeat the tax at the assessment stage but does not preclude discharge when there has been such evasion at the payment stage. The Eleventh Circuit noted that while acknowledging that the result in Haas was correct, the Tenth Circuit in Dalton v. IRS expressly rejected the proposition (adopted in Haas) that section 523(a)(1)(C) applies only to conduct constituting evasion of the assessment of a tax and does not apply to conduct constituting evasion of the payment or collection thereof. Like In re Griffith, Dalton involved only conduct evidencing attempts to evade the payment or collection of taxes. The Griffith court noted that while relying on the broad language of section 523(a)(1)(C)—“willfully attempted in any manner to evade or defeat such tax”—and in particular on the broad phrase “in any manner,” the Dalton court held that section 523(a)(1)(C) makes a tax nondischargeable when the debtor attempted to evade a payment or collection of the tax, even though there was no evasion with respect to the assessment.307 The Dalton court also relied on the purpose of Congress to relieve only “honest” debtors from their tax debts.

The Eleventh Circuit was bound by Haas but indicated that the decision was a candidate for the entire Eleventh Circuit or the Supreme Court to reconsider. The Eleventh Circuit concluded, “[b]ecause we are troubled by the application of the Haas holding to the facts of the instant case, because we doubt that this consequence was argued to the Haas panel, and because of the conflict in the circuits arising from the inconsistency between Haas and Dalton (and the decisions cited therein), we think that the instant case is a candidate for en banc reconsideration.” Griffith was subsequently vacated and affirmed.

The bankruptcy court held that a chapter 7 debtor’s $1 million tax liability is dischargeable, finding that his failure to file returns and pay taxes was the result of his alcoholism, not a scheme to evade taxes.308 The taxpayer was a severe alcoholic for 10 years. During that period he ignored his financial responsibilities and failed to file tax returns. In 1994, after attending Alcoholics Anonymous and becoming sober, the taxpayer pleaded guilty to criminal tax charges. The taxpayer worked with the IRS to file returns and did not destroy records, hide assets, conceal property, or accumulate wealth. After filing for bankruptcy, the taxpayer commenced an adversary proceeding to determine if his 1982 to 1992 taxes, interest, and penalties of more than $1 million were dischargeable.

The bankruptcy court held that the taxpayer’s failure to file returns and pay taxes when he had the resources to pay was not, by itself, willful or dishonest. Citing In re Haas,309 in which the Eleventh Circuit held that not “every knowing failure to pay taxes constitute[s] an evasion of taxes under section 523(a)(1)(C),” the bankruptcy court found the failures to file and pay not part of a tax evasion scheme, but rather it “was simply irresponsible as a result of his alcoholism.”

However, in the case of Fretz, the Eleventh Circuit310 reversed the bankruptcy court’s decision by holding that a bankrupt individual’s failure to file tax returns and to pay taxes is sufficient, even without any supporting affirmative conduct, to show that he willfully attempted to evade or defeat a tax within the meaning of 11 U.S.C. section 523(a)(1)(C)’s nondischarge provision.

The Seventh Circuit has affirmed the denial of a discharge for a couple’s tax debts, based on a bankruptcy court’s findings that the couple willfully attempted to evade tax payment. As part of a chapter 7 case, the couple sought to discharge tax obligations of approximately $2 million for the years 1975, 1977 to 1981, and 1987 to 1988.311

On appeal to the Seventh Circuit, the couple acknowledged that they had transferred cash, stock, and land to their children, created corporations owned by the children but controlled by the husband, paid off undue loans from other creditors while failing to pay their taxes, and lowered the husband’s salary to avoid an IRS levy. However, the couple challenged the bankruptcy court’s findings that their conduct was designed to avoid paying taxes and that they acted willfully.

The Seventh Circuit rejected the couple’s assertion that the bankruptcy court had drawn impermissible inferences from the record. The court noted that because only family members testified without contradiction that the couple’s motives were honest, their testimony was not controlling and that the bankruptcy court simply found the testimony incredible, and the family’s actions speak for themselves. Willfulness, according to the Seventh Circuit, mens rea can be inferred from conduct, and the sum total of the couple’s conduct provided ample basis for finding voluntary, conscious, and intentional attempts to avoid paying taxes.

The district court held that a prior decision by this court decided only that the taxpayers’ trust held assets as a nominee, not that the taxpayers had attempted to evade the payment of taxes.312

The government moved for summary judgment in an attempt to enforce its tax liens because the taxpayers’ 1976–1977 and 1985 tax debts that were subject to prepetition tax liens were not discharged. The government argued that under section 523(a)(1)(C) of the Bankruptcy Code, the taxes would not be discharged because the taxpayers had willfully attempted to evade those taxes. The district court held that the prior decision merely identified the owner of the property in question.

(iv) Penalties

In general, penalties that are a priority item under section 507(a)(8) of the Bankruptcy Code are not dischargeable. Those that are not priority items may be discharged in addition to being subordinated in many cases, as discussed earlier.

One unresolved issue is the extent to which a tax penalty owed on taxes that were due more than three years before the petition was filed can be discharged if the underlying tax is nondischargeable. The Tenth and Eleventh Circuits have held that the penalty is discharged and that section 507(a)(8) of the Bankruptcy Code should be read literally, to allow for the discharge of the tax.313 The Seventh Circuit held differently in Cassidy v. Commissioner.314

The Ninth Circuit also held, in McKay v. United States,315 that the penalty may be discharged even though the tax is not discharged. The tax may not be subject to discharge if it was subject to the two-year requirement under section 523(a)(1)(B)(iii), because the return was filed later or the tax was assessed within 240 days under section 507(a)(8)(A)(ii).

The problem arises because of the conflict of the provisions in subparagraphs A and B of section 523(a)(7) of the Bankruptcy Code. Subparagraph A is generally viewed as a codification of the pre-code position of the government that all noncompensatory penalties are discharged only if the related tax is discharged. However, subparagraph B was added to provide for a discharge of these penalties if they “were imposed with respect to a transaction or event that occurred before three years before the date of the filing of the petition.” The transaction or event is generally held to be the due date or the filing date of the return. Thus, a situation is created in which the tax may not be discharged but the penalty is discharged.

In Burns, the Eleventh Circuit held that any tax penalty imposed with respect to a transaction or event that occurred prior to three years before the date of the filing of a bankruptcy petition would be dischargeable under section 523(a)(7) of the Bankruptcy Code.316 The IRS, in developing a collateral agreement with the taxpayer as reported in In re William Thomas Plachter, Jr.,317 concluded that fraud penalties on taxes that were not dischargeable but were due more than three years before the petition was filed were dischargeable as a result of the debtors’ bankruptcy, in accordance with Burns.

In Ronald Eugene Nye v. United States,318 the district court determined that fraud penalties, incurred on transactions ending more than three years before the filing of the petition, were dischargeable even though the tax to which the penalties related was not dischargeable.

(v) Failure to File Proof of Claim

If the IRS has knowledge of a case and does not file a proof of claim (in the case of a chapter 11 case, the debt is not listed on the schedules), it would appear that once the bar date passes for filing a proof of claim, the IRS has no recourse to collect the tax. In In re Marshall Andrew Ryan,319 the IRS attempted to collect on a prepetition tax claim relating to an earlier chapter 13 case in which the IRS failed to timely file a proof of claim. The bankruptcy court, in a subsequent chapter 13 case by the same debtor, ruled that the prepetition taxes were discharged without payment because the IRS failed to timely file the proof of claim. The IRS also held that postpetition tax claims relating to the earlier case are not discharged because section 1305(a)(1) of the Bankruptcy Code allows the debtor to collect from the plan or directly from the debtor.

In In re Fein,320 the Fifth Circuit held that a priority tax was not discharged even though a proof of claim was not filed and the debt was not listed in the schedules filed. Bruce Fein filed a chapter 11 petition in April 1991, during a period when the IRS was auditing his returns for 1983 to 1986 and 1989. Although Fein did not list the IRS as a creditor, he did notify the IRS of his bankruptcy petition. A proof of claim was not filed by the IRS, and Fein’s plan of reorganization was confirmed in December 1991.

In 1992, the IRS issued a notice of deficiency for the years 1983 to 1985 and 1989, indicating that certain losses with respect to Fein’s participation in a tax shelter were not deductible. Fein objected on the basis that the tax liabilities had been discharged. Both the bankruptcy court and the district court held that the taxes were not discharged.

Citing In re Grynberg321 and In re Gurwitch,322 the Fifth Circuit stated that “in the case of individual debtors, Congress consciously opted to place a higher priority on revenue collection than on debtor rehabilitation or ensuring a fresh start.”

The issuance of a deficiency notice, according to the district court in In re Eddie Burrell,323 does not qualify for the filing of a proof of claim. Eddie Burrell filed a chapter 13 petition on November 18, 1985. The IRS, on December 15, 1985, sent Burrell a deficiency notice, indicating that he owed approximately $100,000 in taxes, interest, and penalties. The IRS did not file a formal proof of claim until after the deadline for filing proofs of claim.

The district court has affirmed the bankruptcy court’s holding that the IRS’s deficiency notice did not reflect “an intent to hold the debtor liable and make demand for payment,” which are crucial factors in detecting the filing of an informal claim. The court noted that a deficiency notice merely notifies the taxpayer of the amount of the tax deficiency and of its right to a redetermination of the amount of the tax.

Even if a proof of claim is filed and the IRS forgets to make a phone call, the claim may be disallowed. In In re William P. Whitney,324 William Whitney, who had previously filed a bankruptcy petition, filed a motion for the court to determine the tax liability based on an IRS proof of claim. The date for a pretrial conference was continued six times. At the request of the IRS, the matter was continued a final time. The pretrial conference was to be via a conference call that the IRS was to initiate, but it failed to make the call. The court disallowed the government’s proof of claim and ordered that it be stricken from the files, noting that the IRS failed to give an adequate reason for not making the conference call.

In the case of a secured lien, the Ninth Circuit BAP held that there is no requirement that the IRS file a proof of claim to protect a secured tax lien.325

For additional discussion of the proof of claims and the importance of filing, see § 10.3(b).

(vi) Impact of Discharge

To obtain proper discharge of a tax, the determination of dischargeability must be made by the court. For the judge to rule on the dischargeability of a tax claim, a dischargeability complaint is filed by the debtor or taxing authority. It would appear that, if neither the debtor nor the taxing authority brings a dischargeability action in the bankruptcy court, the dischargeability of the tax will be decided by nonbankruptcy courts.

Taxes that are commonly discharged include:

- Income tax where filed timely with a due date more than three years prior to the petition date

- Non–trust fund portion of payroll tax returns and all unemployment taxes (with a due date three years prior to the petition date)

- Audit deficiencies assessed over 240 days before the petition, where original returns were filed timely and tax is due more than three years prior to the petition date326

The court held, in In re Andrew Ferrara,327 that, under section 523(a)(7)(B) of the Bankruptcy Code, tax penalties imposed within three years of the filing of a bankruptcy petition are not dischargeable under chapter 7.

Ferrara, a partner in JSA Builders, filed a chapter 7 bankruptcy petition in April 1984. Under Ohio law, Ferrara was liable for the debts of JSA. In July 1984, he was discharged of all debts except taxes, fines, and penalties as provided in section 523 of the Bankruptcy Code. Ferrara had not filed partnership returns for JSA. The IRS assessed penalties against JSA for failure to file timely partnership tax returns. Ferrara argued that he was not liable for the penalties and asked the court to discharge his tax debts. The government claimed that the tax penalties were not dischargeable, because they were incurred within three years of the filing of Ferrara’s bankruptcy petition. See § 11.3(b)(iv).

Taxes that are incurred and not paid by a trustee of an estate of an individual that filed a chapter 7 or chapter 11 petition because of a lack of free assets are not dischargeable and, it appears, are also not transferable back to the individual (see § 4.3(h)). A personal tax that has been discharged only frees the individual from the discharge and does not free any other party that is also responsible for the same debt.328 Thus, if only one spouse files a bankruptcy petition and is discharged of all debts, the IRS could collect from the other spouse if they previously filed joint tax returns. A tax lien on property that is exempt from the bankruptcy estate follows the property and is not discharged by the bankruptcy proceeding.

After the tax has been discharged, the taxpayer should request the IRS to abate the tax and release tax liens, if any. This request is made in a letter specifying the type of tax, period of tax, and taxpayer’s ID number. Included with the letter should be a copy of the discharge and a copy of schedules A-1 and B-4 of the bankruptcy petition. The letter should be sent to the Special Procedures Function in the appropriate district.

Depending on the financial condition of the debtor, the prospects for future income, and other factors, the tax authority may agree to a compromise. Under these conditions, the amount of tax due is generally greater than the ability of the debtor to pay. As part of the compromise, or separately, the IRS may also agree to develop a plan where tax payments are made in installments. Form 433D, Installment Agreement, is used to formalize the payment plan. The most current version of the form may be located at www.irs.gov/pub/irs-pdf/f433d.pdf. This form may be used for agreements reached with the IRS in out-of-court settlements or for the payment of taxes under a plan where, because of events subsequent to confirmation of the plan, the taxpayer is unable to make full payments. An installment payment plan may be entered into while a bankruptcy case is pending, but it will not go into effect until the bankruptcy is dismissed. A compromise and/or an installment agreement may deal with both withholding taxes and other taxes due, such as the employer’s share of Social Security taxes and withheld income taxes.

(vii) Chapter 13

Taxes with priority are not exempt from a discharge under chapter 13; section 1322 of the Bankruptcy Code provides that a plan must allow for the payment of all claims with priority under Bankruptcy Code section 507. Those taxes under section 523 that were not priority taxes for late returns, fraudulent returns, or a failure to file a return were dischargeable before the effective date of the 2005 Act. These taxes are not, however, dischargeable in chapter 7. Section 1328(a)(2) of the Bankruptcy Code was amended by expanding the dischargeability of taxes to cover those taxes that are nondischargeable in chapter 7. Thus, tax discharge for fraudulent and unfiled tax returns under this change is now the equivalent to those in chapter 7. In general, it can be argued that there should be no difference between the dischargeability of taxes under chapter 7 and chapter 13. Chapter 13 facilitates the workout of tax claims and is consistent with other provisions of the 2005 Act that require taxpayers to pay some of their claims over the plan period. Taxing authorities collect substantial taxes because chapter 13 requires that all priority taxes be paid during the plan period, and it places on the tax rolls individuals who have not paid taxes in several years. With this change, the incentive to file chapter 13 has been reduced significantly, and it is expected that most chapter 13 petitions will be filed by those who are not eligible for chapter 7 because the debtor has income above the median income.

However, in chapter 7, prior-year tax returns are often not filed and limited amounts, if any, of the taxes are paid during the collection period. In the final analysis, taxing authorities may receive a very small percentage of the taxes due and probably less than would have been received in chapter 13. Prior law provided that the section 523 taxes were not dischargeable if payments provided for in the plan were not made and the chapter 13 debtor received a hardship discharge.

The 2005 Act amended section 1325 of the Bankruptcy Code to provide that one of the requirements for plan confirmation is the filing of income tax returns required under a new section 1308 of the Bankruptcy Code. Section 1307 of the Bankruptcy Code is amended to provide that upon the failure of the debtor to file the returns required under section 1308, on request of a party in interest or the U.S. trustee and after notice and a hearing, the court shall dismiss or convert the chapter 13 case to chapter 7, whichever is in the best interest of the estate.

Section 502(b)(9) as amended provides that an objection to the confirmation of a plan is considered to be timely if it is filed within 60 days after the debtors’ tax returns were filed under section 1308. Additionally, Congress directed the Advisory Committee on Bankruptcy Rules of the Judicial Conference to propose rules that provide for an opportunity for governmental units to object to the confirmation of a plan, on or before 60 days after the debtor files all tax returns required under sections 1308 and 1325(a)(7) of the Bankruptcy Code. The proposed rules were to provide that no objection can be filed in reference to a tax return required to be filed under section 1308, until such return has been filed as required.

Section 1308 provides that no later than the day before the date on which the meeting of the creditors is first scheduled to be held under section 341(a), if the debtor was required to file a tax return under applicable nonbankruptcy law, the debtor must file with appropriate tax authorities all tax returns for all taxable periods ending during the four-year period ending on the date of the filing of the petition. If the tax returns have not been filed by the date on which the meeting of creditors is first scheduled to be held under section 341(a), the trustee may hold open that meeting for a reasonable period of time to allow the debtor an additional period of 120 days to file the return that is past due as of the petition date. For returns that are not past due, the time period is the later of the 120 days or the date on which the return is last due under the last automatic extension the debtor is entitled under nonbankruptcy law.

If the debtor demonstrates by preponderance of the evidence that the failure to file a return is attributable to circumstances beyond the control of the debtor, the court may extend the filing period established by the trustee under this subsection for 30 days for delinquent returns and for a period not to extend beyond the applicable extended due date for a return that was not past due as of the filing date. For purpose of section 1308, the term “return” includes a return prepared pursuant to subsection (a) or (b) of section 6020 of the Internal Revenue Code of 1986, or a similar state or local law, or a written stipulation to a judgment or a final order entered by a nonbankruptcy tribunal.

The requirement for the debtor to file these tax returns was proposed by the Tax Advisory Committee appointed by the NBRC because it was believed that this provision would help reestablish the chapter 13 debtor as a “taxpayer” and would determine the priority tax that must be paid for a debtor to qualify for the chapter 13 super discharge. Additionally, allowing the super discharge to continue would most likely result in the taxing authorities collecting more taxes now, and in the future, than would be collected with the filing of a chapter 7 petition. With the repeal of the chapter 13 tax discharge provisions, tax professionals generally will not recommend that clients file chapter 13. As a result, this provision will not have the impact that was intended.

A bankruptcy judge, in In re Alyce M. Sampson,329 held that a plan in a chapter 13 case that provided nothing for unsecured creditors, including the IRS, resulted in all debts included in the plan being discharged, including the tax claims. In In re Irving C. Newcomb, Jr.,330 the court held that first-quarter tax liability for withholding and FICA taxes was dischargeable because a proof of claim was not filed. The IRS had filed a proof of claim for the second and third quarters, and the judge did allow the IRS to file an amended proof of claim, ruling that a new claim was not asserted but that the proof of claim was filed to correct a defect in the claim originally filed.

Once a chapter 13 plan has been completed, the IRS should not attempt to collect prepetition taxes, according to the bankruptcy court in In re Mary Germaine.331

The IRS seized Mary Germaine’s 1989 and 1990 income tax refunds and sent notice of intent to levy for prepetition taxes, after Germaine had filed a chapter 13 petition and completed her plan of reorganization in March 1990. Germaine filed a motion directing the IRS (1) to permanently abate collection of 1981 Federal Unemployment Tax Act (FUTA) taxes she allegedly owed, to bar the IRS from auditing her prepetition taxes, and (2) to return her 1990 income tax refund. This case was settled by an agreement that the IRS would abate the collection of the 1981 FUTA taxes, return the 1990 refund, and treat all taxes that accrued prior to the date of the chapter 13 petition as paid in full or discharged.

Germaine also moved for attorney’s fees and costs. The bankruptcy court found that it had jurisdiction to hear the claim for attorney’s fees because the claim arose out of the same transaction as the IRS’s claim against Germaine. The court also held that because she had exhausted her administrative remedies and the government’s position was not substantially justified, she was entitled to $2,000 in attorney’s fees.

On appeal, the Ninth Circuit BAP affirmed the award for damages against the IRS.332 The BAP, in affirming the bankruptcy court decision, held that Bankruptcy Code section 106(a) did not apply to waive the IRS’s sovereign immunity as to Germaine’s claim for damages because the cause of action against the IRS belonged to the debtor, rather than to the estate, and because the IRS’s claim was not against the bankruptcy estate.

In Henry Robert Grewe,333 the bankruptcy court allowed damages in a chapter 7 case where the taxes were discharged.

Section 1328(b) of the Bankruptcy Code provides for an early discharge of debts that were scheduled for payment in the plan if the debtor is, under certain conditions, unable to make these payments. The provisions of Bankruptcy Code section 523(a) are fully applicable to this subsequent discharge, which means that taxes with priority are exempt from discharge, as are taxes resulting from the misconduct of the debtor.

On appeal, the Fourth Circuit determined that the Grewes were not entitled to recover attorney’s fees because they failed to exhaust their administrative remedies before filing suit in the bankruptcy court.334

In In re Nelson,335 Terry Nelson filed for chapter 13 bankruptcy, and his plan of reorganization stated that the IRS priority tax claims were to be paid nothing. The IRS received notice of the bankruptcy and the motion for confirmation of the plan but did not object to the plan before the bankruptcy court confirmed it. The plan was confirmed before the time for filing claims had expired. The IRS filed a timely tax claim. However, the district court affirmed the decision of the bankruptcy court that disallowed the claim of the IRS. The district court noted that the government admitted that the IRS chose not to respond after receiving adequate notice of confirmation of the proposed plan. This lack of response constituted tacit approval. The court also added that the IRS was not prejudiced by the procedure but that dismissal of the bankruptcy case after it had been fully administered would have been highly prejudicial to the debtor and all the other creditors.

A couple’s motion to reconsider the dismissal of their chapter 13 case was denied because their continued failure to file tax returns—despite being given ample opportunity to do so—indicated their lack of good faith.336

A tax with respect to which the debtor made a fraudulent return or willfully attempted to evade or defeat such tax is dischargeable under the general chapter 13 discharge provision of section 1328(a) of the Bankruptcy Code.337 The taxpayers filed a chapter 13 petition in January 1991, and subsequently their chapter 13 plan, which provided for full payment of all unsecured priority claims, was confirmed, but neither the original nor the amended plan schedules provided for payment of the IRS’s allowed claim for 1986 tax due on unreported income earned through embezzlement. The taxpayers argued that the IRS’s unsecured claim was for tax due more than three years before the petition, and as a result no priority is granted tax debts arising from a fraudulent return. The IRS, however, based its claim to priority status on the six-year exception of I.R.C. section 6501(e)(1)(A) to the general three-year assessment period for omissions of income greater than 25 percent of the income reported.

The bankruptcy court held that tax liabilities were not entitled to unsecured priority claim treatment and were dischargeable in a chapter 13 case, even though the debtors’ return, filed less than six years before their bankruptcy filing, fraudulently contained a substantial omission of income. The bankruptcy court, quoting section 523(a)(1)(C) of the Bankruptcy Code, held that a tax with respect to which the debtor made a fraudulent return or willfully attempted to evade or defeat such tax is dischargeable under the general chapter 13 discharge provision of section 1328(a) of the Bankruptcy Code. The court noted that the result would be different in a chapter 7, 11, or 12 individual case, in which the liability would not be discharged and as a result the taxing authority could pursue a debtor after the bankruptcy case. The court found no ambiguity in Congress’s intent to afford dischargeability under chapter 13. Thus, based on the plain language of section 507(a)(8)(A)(iii) of the Bankruptcy Code, which excepts from priority status tax of a kind specified in section 523(a)(1)(C), the bankruptcy court ruled that sections 507(a)(8)(A)(iii) and 523(a)(1)(C) of the Bankruptcy Code dictate that a tax resulting from fraud is not entitled to priority status, even though the tax might otherwise be assessable under the six-year statute of limitations for substantial omissions.

The Fourth Circuit, in a one-paragraph per curiam opinion, upheld the dismissal of a chapter 13 bankruptcy case, because the individual debtor failed to provide for full payment of a federal tax claim that was allowed in his chapter 13 plan.338

In In re Hairopoulos,339 the debtor provided in the chapter 13 plan that all priority taxes were to be paid, but because the debtor did not file a proof of claim on a timely basis in this no-asset case, the tax was not allowed. The district court concluded that the tax debts were not provided for in the chapter 13 plan because the IRS had not received notice of the case in time to file a timely claim. On appeal, the Eighth Circuit held that a claim cannot be considered to have been provided for if a creditor does not receive proper notice of the proceedings. The court noted that the constitutional component of notice is based on recognition that creditors have a right to adequate notice and the opportunity to participate in a meaningful way in the course of bankruptcy proceedings. The appeals court concluded that the no-asset notice given to the IRS was insufficient to satisfy due process and fundamental fairness. The court disagreed with the debtor that the IRS had a duty to seek leave to file a late proof of claim, because such a requirement would undermine “the very rationale for granting parties the right to participate in bankruptcy proceedings.”

(viii) Chapter 11 Cases Filed by Individuals

If an individual debtor filing is determined to be abusive, the chapter 7 petition will be dismissed unless the debtor converts it to chapter 11 or 13. To provide at least some similarities between chapters 11 and 13, the code modified chapter 11 to make the proceedings for individuals similar to those in chapter 13. For tax purposes, this change has created several problems because a separate bankruptcy estate is created when an individual files a chapter 11 petition but not a chapter 13 petition. It is expected that the IRS will issue some guidelines or modify the I.R.C. to handle these tax problems. The major changes to chapter 11 are described next.

(A) Property Acquired Postpetition Including Earnings

I.R.C. section 1115 is modified by the following provision:

(a) In a case in which the debtor is an individual, property of the estate includes, in addition to the property specified in section 541—

(1) All property of the kind specified in section 541 that the debtor acquires after the commencement of the case but before the case is closed, dismissed, or converted to a case under chapter 7, 12, or 13, whichever occurs first; and

(2) Earnings from services performed by the debtor after the commencement of the case but before the case is closed, dismissed, or converted to a case under chapter 7, 12, or 13, whichever occurs first.

(b) Except as provided in section 1104 or a confirmed plan or order confirming a plan, the debtor shall remain in possession of all property of the estate.

Thus, all property and earnings of the individual debtor become property of the estate. In chapter 13, debtors continue to file their own tax returns, and no separate estate is created; the opposite is true in chapter 11, where there is a separate estate. From a tax perspective, the problems created by this difference are significant. The employee will continue to receive a W-2 form reporting earnings for personal services, yet the earnings are property of the estate. Considerable uncertainty now exists as to how to account for the income earned by individual debtors and will continue until some form of explanation is received from the IRS. One option is to report the income on the tax return filed by the estate, if in fact the earnings go to the estate, as specified by I.R.C. section 1155. Individual debtors would report on their tax return any funds that the estate disbursed to them for living and other related expenses. The disbursement of these funds by the estate should be based on an order issued by the bankruptcy court. Most likely these disbursements would be reported by the estate on Form 1099 and deducted by the estate as an administrative expense. Under this option, it would appear that the estate would be entitled to the tax benefit associated with the withholdings, and the debtor would be responsible for any taxes that are due on the disbursements received from the estate. In this case, the court would need to allow the tax payments as a necessary administrative expense in determining the amount to be used for living expenses.

Another option is to have individual debtors report these earnings on their individual income tax returns. Any payments to the estate would then be allowed as a deduction for adjusted gross income. Alternatively, a better option may be for the estate to not report the receipts as income because the estate is simply receiving property from the debtor that is not subject to a tax. Such payments could be considered payments of debt and thus would not be subject to a deduction.

Sam Young, quoting W. Robert Pope, noted that the only way to determine necessary expenditures, which for a business are normally documented, is to obtain approval from the bankruptcy court.340

To avoid some of these issues, the I.R.C. might be modified to provide that a separate estate is not created for chapter 11, but additional problems would be created.

The IRS’s solution to the problem, which might be a temporary one, is described in Notice 2006-83. Under section 1115 of the Bankruptcy Code, the IRS noted that earnings from a chapter 11 debtor’s postpetition services, including self-employment income, are property of the estate and includible in the income of the estate rather than of the debtor. I.R.C. section 1398(e)(1). However, neither section 1115 of the Bankruptcy Code nor section 1398 of the I.R.C. addresses the application of the self-employment tax to the earnings from the individual debtor’s continuing services. Because the debtor continues to derive gross income from the performance of services as a self-employed individual after the commencement of the bankruptcy case, the debtor must continue to report on Schedule SE of the debtor’s individual income tax return the self-employment income earned postpetition, which includes attributable deductions, and must pay the resulting self-employment tax.

Notice 2600-83 notes that as a result of the enactment of section 1115, postpetition wages earned by a debtor are generally treated for income tax purposes as gross income of the estate rather than of the debtor. However, reporting and withholding obligations by a debtor’s employer have not changed; section 1115 has no effect on the application of FICA or FUTA, or on Federal Income Tax Withholding. With respect to wages of a chapter 11 debtor in a case commenced on or after October 17, 2005, an employer should continue to report wages and withholdings on a Form W-2 issued to the debtor’s name and Social Security number.

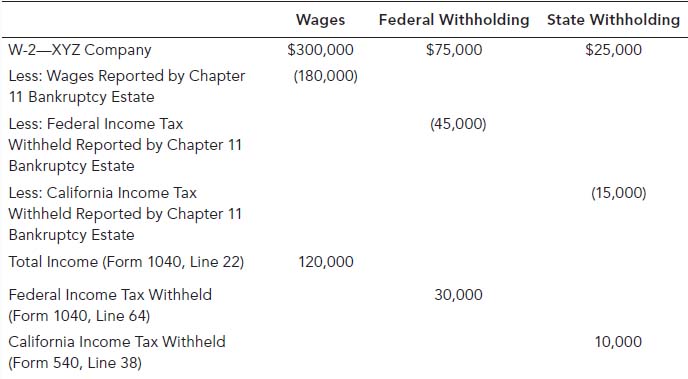

When an employer issues a Form W-2 to a chapter 11 debtor reporting all of the debtor’s wages, salary, or other compensation for a calendar year, and a portion of the wages, salary, and other compensation represents earnings from postpetition services included in the estate’s gross income under section 1398(e)(1), an allocation of the amounts reported on the Form W-2 must be made. The debtor in possession or trustee, if appointed, must reasonably allocate between the debtor and the estate the wages, salary, or other compensation and the income tax withheld. The allocations must be in accordance with all applicable rules. The debtor or trustee may use a simple percentage method, if reasonable, for allocating income and tax withheld between the debtor and the estate. In all cases, the same method must be used for both income and withholdings.

In some cases, filers of information returns may report to the debtor gross income, gross proceeds, or other reportable payments that should have been reported to the bankruptcy estate using Forms 1099-INT, 1099-DIV, 1099-MISC, Schedule K-1, or other information returns. In these cases, the debtor in possession or trustee must allocate the reported income in a reasonable manner so that any income and tax withheld attributable to the postpetition period is reported on the estate return, and any income and tax withheld attributable to the prepetition period is reported on the debtor’s return. Allocations must be made in accordance with all applicable rules.

To report the allocations between debtor and estate returns, the debtor must attach a statement to his or her individual income tax return indicating a chapter 11 case was filed, showing the amounts of income and withholdings allocated between the debtor and the estate, and describing the method used for allocation. The filing date, bankruptcy court in which the case is pending, court case number, and bankruptcy estate’s Employer Identification Number (EIN) should also be included. The debtor in possession and trustee must attach a similar statement to the income tax return of the estate.

Exhibit 11.1 is an example of information that might be presented for an allocation.

Exhibit 11.1 Allocation between Debtor and Estate

This section of Notice 2006-83 deals with the allocation of the prepetition wages and income with income received after the petition was filed. In many cases, another issue must be addressed after the petition is filed. If the court allows a part of the income to be used by the debtor for various purposes, including a living allowance, the question not directly answered by the notice is how income is allocated between the estate and the individual debtor. Informally, the IRS has indicated that the same policy described in section 06 of Notice 2006-83 may be followed.

Pope noted that under a literal interpretation of Bankruptcy Code section 1115, “all of the bankrupt’s income belongs to the estate, which is at odds with the traditional practice of allowing the bankrupt taxpayer some income for necessary expenses.”341

Even with all of the problems described with Bankruptcy Code section 1115, the use of chapter 11 by individuals is still more desirable than an out-of-court settlement with the IRS using offers in compromise.

(B) Future Earnings in Plan

A new paragraph is added to I.R.C. section 1123(a) making it mandatory for an individual to provide future income earned by the individual as part of the funding of a plan. Section 1123(a)(8) as modified provides:

(8) in a case in which the debtor is an individual, provide for the payment to creditors under the plan of all or such portion of earnings from personal services performed by the debtor after the commencement of the case or other future income of the debtor as is necessary for the execution of the plan.

(C) Plan Confirmation

A new paragraph is added to I.R.C. section 1129(a) requiring the debtor to include in the plan at least a five-year minimum contribution of disposable income as defined in I.R.C. section 1325(b) (see § 1. 2(h)) when an unsecured creditor objects.

(15) In a case in which the debtor is an individual and in which the holder of an allowed unsecured claim objects to the confirmation of the plan—

(A) the value, as of the effective date of the plan, of the property to be distributed under the plan on account of such claim is not less than the amount of such claim; or

(B) the value of the property to be distributed under the plan is not less than the projected disposable income of the debtor (as defined in section 1325(b)(2)) to be received during the 5-year period beginning on the date that the first payment is due under the plan, or during the period for which the plan provides payments, whichever is longer.

(D) Domestic Support Obligations