CHAPTER FIVE

Corporate Reorganizations

§ 5.1 Introduction

(a) Importance of Reorganization Provisions in Bankruptcy and Insolvency Restructuring

(b) Exception to the General Rule of Taxation

(c) Overview of Section 368

§ 5.2 Elements Common to Many Reorganization Provisions

(a) Overview

(b) Business Purpose

(c) Continuity of Business Enterprise

(i) COBE Regulations for Transactions prior to October 25, 2007

(ii) COBE Regulations for Transactions after October 25, 2007

(d) Continuity of Interest

(i) Signing Date Rule

(e) Control

(f) Contingent and Escrowed Shares

(g) Tax Treatment: Operative Provisions

(h) Substance over Form and Step Transaction Doctrines

§ 5.3 Overview of Specific Tax-Free Reorganizations under Section 368

§ 5.4 Acquisitive Asset Reorganizations

(a) A Reorganization: Merger or Consolidation

(b) C Reorganization

(i) Overview

(ii) “Substantially All”

(iii) Liquidation

(iv) Distribution to Creditors

(c) Triangular Asset Acquisitions

(d) Acquisitive D Reorganization

(i) Overview

(ii) “Substantially All”

(iii) Distribution of Stock

(iv) Control

(v) Section 357(c)

(A) Current Law

(B) Prior Law

(vi) Other Issues

§ 5.5 Stock Acquisitions

(a) B Reorganization

(i) Overview

(ii) “Solely for Voting Stock”

(iii) Control

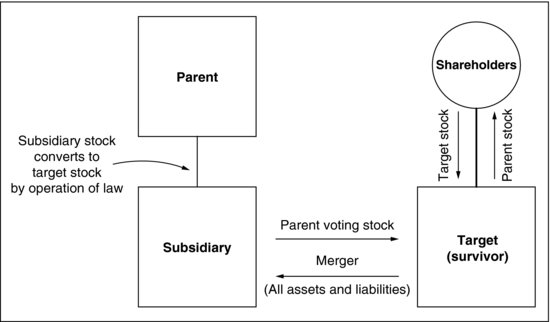

(b) Reverse Triangular Mergers

(i) Overview

(ii) Basis

(iii) “Substantially All,” “Drops,” and “Pushups”

(iv) Forward and Reverse Mergers: Other Consequences

§ 5.6 Single-Entity Reorganizations

(a) E Reorganization

(b) F Reorganization

§ 5.7 Divisive Reorganizations

(a) Overview

(b) Types of Corporate Divisions

(c) Requirements for Tax-Free Treatment of Corporate Divisions

(i) Control

(ii) Distribution of Control

(iii) Active Conduct of a Trade or Business

(iv) Five-Year History

(v) Continuity of Interest

(vi) Disqualified Distribution under I.R.C. Section 355(d)

(vii) Business Purpose

(viii) Device

(ix) I.R.C. Section 355(e)

(x) I.R.C. Section 355(f)

(d) Spin-offs and Losses

(e) Rev. Proc. 2003-48 and I.R.C. Section 355 Rulings

§ 5.8 Insolvency Reorganizations

(a) Insolvency Reorganization other than G Reorganizations

(i) Introduction

(ii) Seminal Cases: Alabama Asphaltic and Southwest Consolidated

(iii) Final Regulations: Application of the Continuity of Interest Requirement to Reorganizations of Insolvent Corporations and/or Corporations in a Title 11 or Similar Case

(A) History of the Continuity of Interest Requirement in Bankruptcy Reorganizations

(B) Creditor Continuity outside Bankruptcy

(C) Final Regulations

(D) Conclusion

(iv) Recapitalizations Coupled with Insolvency Reorganizations

(v) Norman Scott

(vi) Exchange of Net Value Requirement

(b) G Reorganization

(i) Purpose

(ii) Transfer of Assets

(iii) “Substantially All”

(iv) Triangular G Reorganization

(v) Dominance of G Reorganization

(vi) Tax Treatment

§ 5.9 Summary

§ 5.1 INTRODUCTION

(a) Importance of Reorganization Provisions in Bankruptcy and Insolvency Restructuring

As noted in § 1.1, it is not uncommon for a corporation in bankruptcy to realize taxable income during the administration of a bankruptcy proceeding. An insolvent corporation is also likely to have significant historical losses, which might, under the proper circumstances, be available to offset both current and future taxable income. Preservation of historical losses is complicated if a corporation’s debt restructuring involves transactions with other corporations. The particular limitations the Internal Revenue Code (I.R.C.) places on the use of historical losses are discussed in Chapter 6. To understand these limitations, however, it is necessary to have an understanding of the tax treatment of the various forms of corporate reorganization. That is the function of this chapter.

(b) Exception to the General Rule of Taxation

A reorganization is an exception to the general rule that, upon the exchange of property, any gain or loss realized will be recognized. The very purpose of the reorganization provisions of the I.R.C. is to except from the general rule the specific exchanges described in those provisions.1 Thus, if a transaction qualifies as a reorganization, gain or loss realized in the transaction will, in general, not be recognized at either the corporate2 or shareholder3 level. The gain or loss, however, does not disappear; rather, it is preserved in the tax basis of the property received in the reorganization, which generally will be the same as the basis of the property exchanged.4 The nature of the gain—long-term or short-term—is also preserved: The holding period of the property exchanged in the reorganization is “tacked on” to the property received.5 The rationale for the exception to the general gain/loss recognition provisions is that reorganization constitutes a mere readjustment of a continuing interest in property under modified corporate form.

(c) Overview of Section 368

I.R.C. section 368 defines the transactions that qualify as reorganizations and excludes all others. In general, I.R.C. section 368 describes three types of transactions: (1) asset acquisitions, including type A mergers, forward triangular mergers, and C, D, and G reorganizations; (2) stock acquisitions, including B reorganizations and reverse triangular mergers; and (3) single-entity reorganizations, including E and F reorganizations. Divisive reorganizations that meet the requirements of I.R.C. section 355 will be tax free and may also qualify as D or G reorganizations.

§ 5.2 ELEMENTS COMMON TO MANY REORGANIZATION PROVISIONS

(a) Overview

All the reorganization provisions require a business purpose for undertaking the transaction. Reorganizations also generally require continuity of business enterprise (COBE) and continuity of interest (COI).6 These requirements have stood the test of time in the courts. They have, however, significantly evolved through the regulatory process. The tax treatment that follows from compliance with the reorganization provisions is essentially the same for each reorganization.

Therefore, instead of considering many of the judicial and statutory provisions applicable to each reorganization separately, those precepts applicable to two or more reorganizations are discussed. Although the “solely for voting stock” and “substantially all” requirements are common to a number of reorganizations, they are covered separately with each reorganization.

(b) Business Purpose

The Treasury Regulations provide that a reorganization (1) must be undertaken for reasons that are “germane to the continuance of the business of a corporation”7 or (2) must be “required by business exigencies.”8 Thus, a transaction that meets the literal requirements of a reorganization under I.R.C. section 368 may fail to qualify due to a lack of a business purpose if it is undertaken purely for tax avoidance or if it is a “sham.” To withstand a sham transaction attack, a transaction must have a legitimate business purpose. Some commonly accepted business purposes include to achieve operating efficiencies, to penetrate new markets, or to diversify into new product lines.

(c) Continuity of Business Enterprise

Many types of reorganization must result in a COBE. Prior to 1980, all that was necessary to satisfy COBE was that the acquiring corporation be engaged in business activity.9 In 1980, an initial set of Treasury Regulations were promulgated that required the acquiring corporation to either continue the historical trade or business of the target corporation (business continuity) or use a significant portion of the target corporation’s assets in a trade or business (asset continuity).10 A set of Treasury Regulations that altered the COBE requirements was issued in 1998.11 These COBE regulations maintained the business continuity and asset continuity concepts of the 1980 Treasury Regulations. That is, to satisfy COBE, the acquiring corporation must either continue a significant historical business of the target corporation or use a significant portion of the target corporation’s historical business assets in a business.12 Examples in the regulations indicate that one-third will be “significant” for either purpose.13 COBE is measured only with respect to the assets or activities of the target corporation and is not based on the acquiring corporation’s historical activities.14

COBE is generally not violated when the stock or assets received in the reorganization are transferred or “dropped” to a controlled corporation.15 I.R.C. section 368(a)(2)(C) only allows transfers to controlled subsidiaries following A, B, C, or G reorganizations. In Revenue Ruling (Rev. Rul.) 2002-85,16 the IRS added D reorganizations to that list.17 The IRS reached this conclusion despite the fact that the permissive language of I.R.C. section 368(a)(2)(C) does not include D reorganizations. The COBE requirement is not applicable to E and F reorganizations pursuant to final regulations issued in 2005.18 In 2007, the IRS issued final COBE regulations for transactions occurring after October 25, 2007. The final COBE regulations provide additional guidance regarding the effect of certain transfers of stock or assets on the continuing qualification of a transaction as a tax-free reorganization.19

(i) COBE Regulations for Transactions prior to October 25, 2007

The COBE regulations take this concept several steps further by permitting the acquiring corporation to transfer, or to cause other controlled corporations to transfer, the target corporation’s assets or stock to and among members of a “qualified group” without violating COBE.20 The regulations accomplish this by treating the acquiring corporation21 as holding all the businesses and assets held by the members of the “qualified group.” A qualified group is one or more chains of corporations connected through stock ownership with the acquiring corporation.22

The application of the COBE regulations must often be applied hand in hand with Treas. Reg. section 1.368-2(k), which extends I.R.C. section 368(a)(2)(C) by permitting a transfer or successive transfers following certain reorganizations, provided each transferor controls each transferee within the meaning of I.R.C. section 368(c). If the requirements of Treas. Reg. section 1.368-2(k) are satisfied, a post-reorganization distribution or other transfer will neither disqualify the otherwise tax-free reorganization nor cause it to be recharacterized.

The COBE regulations restrict drop-downs of assets or stock to the genus of property acquired in the reorganization.23 Thus, in an asset reorganization, assets can be dropped; in a stock reorganization, stock can be dropped. For this purpose, reverse triangular mergers under I.R.C. section 368(a)(2)(E) are treated as both stock and asset reorganizations, thereby permitting the subsequent drop-down of either stock or assets.24 The IRS has extended this treatment to forward triangular mergers.25

One of the major relaxations of the COBE doctrine introduced by the COBE regulations involves the use of partnerships. In general, for purposes of evaluating asset continuity, the acquiring corporation is treated as owning the assets of the partnership in accordance with the qualified group’s aggregate partner interest in the partnership.26 For purposes of evaluating business continuity, the acquiring corporation will be treated as conducting a business of the partnership if:

- One or more members of the qualified group own in the aggregate an interest in the partnership representing a significant interest (at least one-third) in that partnership business,27 or

- One or more members of the qualified group have active and substantial management functions as a partner with respect to that partnership business, and the qualified group has a requisite interest in the partnership. (Examples indicate that a 1 percent interest will not satisfy the requisite interest component and that a 20 percent interest will.)28

Once the partnership assets and partnership business are attributed to the acquiring corporation in accordance with the rules outlined above, COBE is tested under the general requirement that the acquiring corporation either continue the target corporation’s historical business or use a significant portion of the target corporation’s historical business assets in a business.

The COBE regulations caution, however, that the Step Transaction doctrine will apply in determining whether the transaction is otherwise a tax-free reorganization.29 Thus, under the pre–October 25, 2007, regulations to be discussed, a transfer of the target corporation’s stock to a partnership after a B reorganization may satisfy COBE (good news) but nevertheless fail to satisfy the more basic I.R.C. section 368(a)(1)(B) requirement of “control immediately after” (bad news), rendering the putative reorganization taxable.30 Notice the distinction between the transfer of the target corporation’s stock after a stock reorganization to a partnership (not permitted) and a transfer of the target corporation’s assets after an asset reorganization to a partnership (permitted). Implicit in the entire regulation is the fact that the transfer of assets to a partnership after an A, C, D, or G reorganization was permitted under the prior regulations, even though no such transfer is described in I.R.C. section 368(a)(2)(C) and even though under the Step Transaction doctrine, no such tolerance would be allowed. Similarly, it appears that such transfers to partnerships should be permitted in D and F reorganizations.31 As discussed next, the current regulations now permit transfers of assets or stock to partnerships.

(ii) COBE Regulations for Transactions after October 25, 2007

On October 24, 2007, the IRS issued final COBE regulations expanding the definition of a qualified group, continuing the trend of broadening the rules as to transfers of stock or assets following an otherwise tax-free reorganization when the transaction adequately preserves the link between former target shareholders and target’s business assets.32

The definition of a qualified group now contains an aggregation concept that permits qualified group members to aggregate their direct stock ownership to determine whether they own the requisite section I.R.C. section 368(c) control in the corporation (provided the issuing corporation owns directly stock meeting the control requirement in at least one other corporation). Additionally, the definition of a qualified group permits the attribution of stock owned by certain partnerships.33 Stock owned by a partnership is now treated as owned by members of the qualified group if the partnership interests owned by members of the qualified group meet the control definition in I.R.C. section 368(c).34

As a result of the final COBE regulations, a transfer or drop of (1) stock or assets of a target corporation received in a reorganization, (2) assets of a target corporation that continues to exist after a reorganization (e.g., after an I.R.C. section 368(a)(1)(B) reorganization or an I.R.C. section 368(a)(2)(E) reverse triangular merger), or (3) stock in the acquiring corporation (e.g., after an I.R.C. section 368(a)(2)(D) forward triangular merger) to a member of a qualified group will not violate the COBE or control requirements.

The final COBE regulations provide additional guidance regarding the effect of certain transfers of stock or assets on the continuing qualification of a transaction as a tax-free reorganization. Specifically, a transaction otherwise qualifying as a reorganization under I.R.C. section 368(a) will not be disqualified or recharacterized as a result of one or more subsequent transfers (or successive transfers) of assets or stock, provided the COBE requirement is satisfied and the transfer(s) qualify as a distribution or other transfer.35

To qualify as a “distribution,” the distribution must not constitute a liquidation for federal income tax purposes. More specifically, it must not include all the assets of the acquired corporation, the acquiring corporation (disregarding assets held before the reorganization), or the surviving corporation (disregarding assets of the merged corporation).36 In the case of a distribution of the acquired corporation’s stock, the distribution must be less than the amount of the stock acquired, and the distribution cannot cause the acquired corporation to cease being a member of the qualified group.37 Furthermore, indirect distributions of assets are treated in the same manner as a direct distribution of those assets.38

To qualify as an “other transfer” (a transaction that does not constitute a distribution of assets or stock, or both, of the acquired corporation, the acquiring corporation, or the surviving corporation, as the case may be), the acquired corporation, the acquiring corporation, or the surviving corporation cannot terminate its corporate existence in connection with the transfer(s).39 In addition, the transfer of stock cannot cause the acquired corporation, the acquiring corporation, or the surviving corporation to cease being a member of the qualified group.

Finally, transfers of stock of a corporation to a controlled partnership (i.e., one in which members of the qualified group own interests meeting the requirements equivalent to I.R.C. section 368(c)) adequately preserve the affiliation between the former target shareholders and the target business assets.40 As a result, a transfer of stock to a controlled partnership following a B reorganization no longer fails the I.R.C. section 368(a)(1)(B) requirement of “control immediately after.” In contrast, transfers made prior to the effective date of the final regulations (October 25, 2007) fail the I.R.C. section 368(a)(1)(B) requirement of “control immediately after,” rendering the purported reorganization taxable. On May 8, 2008, Treasury released another set of final regulations (T.D. 9396) that clarified certain aspects of the October 2007 final COBE regulations discussed earlier.

(d) Continuity of Interest

There must be a COI in a reorganization. In general, this means that a substantial part of the value of the proprietary interest in the target corporation must be preserved in the reorganization. The proprietary interest in a target corporation is preserved if it is exchanged for a proprietary interest in the acquiring corporation or a corporation that is in control of the acquiring corporation in the case of a triangular reorganization.41 Only stock ownership (either voting or nonvoting) can satisfy this test; cash, short-term notes, bonds, and options or warrants do not convey proprietary rights and will not, therefore, establish the needed COI.42 This requirement is designed to distinguish a tax-free reorganization from a taxable sale.

The question of how much stock of the acquiring corporation must be received by the shareholders is not entirely settled. It was previously the case that to obtain an advance ruling from the IRS, the taxpayer had to represent for COI purposes that the stock of the acquiring corporation received by the shareholders of the target corporation had a fair market value equal to or greater than 50 percent of the fair market value of the target corporation’s stock outstanding immediately prior to the transaction.43 Despite the safe harbor rule, it is generally agreed that 38 percent is sufficient.44

Treasury Regulations issued in 1998 changed the playing field with regard to this requirement.45 The most significant change resulting from the COI regulations is that a target corporation’s shareholders that receive acquiring corporation stock in a reorganization may dispose of that stock (even as part of the overall plan of reorganization and pursuant to a binding agreement) without violating the COI requirement.46 This was a liberalization of the test enunciated in prior case law, under which the shareholders of the target corporation were required to maintain stock ownership in the acquiring corporation.47 The regulations generally changed the COI focus from the retention of an equity interest to an evaluation of the consideration issued in the reorganization. In addition, the COI regulations expanded proposed regulations by generally permitting pre-reorganization dispositions of target corporation stock.48

This permissive approach to dispositions of stock in connection with reorganizations is tempered by exceptions that focus on a target shareholder’s receipt (or deemed receipt) of nonstock consideration, or “boot.” Section 356 generally addresses the receipt of boot in a reorganization. Evaluation of the extent to which boot has been received requires a determination of whether a pre-reorganization distribution or redemption should be treated as boot in the reorganization or a separate transaction. Such determinations involve many unresolved issues. In general, COI will be impaired to the extent consideration received by a target shareholder prior to a reorganization (either in a redemption of target corporation stock or in a distribution with respect to target corporation stock) is treated as boot.49 Also, COI will generally be impaired to the extent that, in connection with a reorganization, target stock is acquired for consideration other than stock of the acquiring corporation (i.e., boot in the reorganization) or to the extent the stock consideration is redeemed.50

Finally, COI will be impaired to the extent that, in connection with a reorganization, a party that is related to the acquiring corporation acquires with property other than stock of the acquiring corporation, stock of the target corporation, or stock consideration that was furnished in exchange for stock of the target corporation.51 In general, corporations in the same affiliated group as the acquiring corporation are considered related persons, and some corporations that are only related by 50 percent ownership are considered related persons.52 This related party acquisition impairment to COI will not apply in two circumstances: (1) If persons who were the direct or indirect owners of the target stock prior to the reorganization maintain a direct or indirect interest in the acquiring corporation, COI will be satisfied;53 and (2) if a reorganization occurs following a qualified stock purchase (QSP), COI will be satisfied despite the fact that 80 percent or more of the stock of a target has been purchased by a related corporation.54

The preamble to the COI regulations indicates that the IRS is continuing to study the role of the COI requirement in D reorganizations and I.R.C. section 355 transactions. Therefore, the COI regulations that were issued in 1998 did not apply to D reorganizations or to I.R.C. section 355 transactions.55 Although it is unclear, the portion of the regulation that was not modified continues to indicate that COI is not applicable to a D reorganization.56

A reorganization, then, is generally a transaction described in I.R.C. section 368, undertaken for a bona fide business purpose, that satisfies both COBE and COI.57 However, the COI requirement is not applicable to E and F reorganizations pursuant to regulations issued in 2005.58

(i) Signing Date Rule

In 2007, temporary and proposed regulations (the 2007 Regulations) were issued updating prior regulations to address when COI is measured.59 By way of background, final regulations, issued in September 2005 (the 2005 Regulations), established a signing date rule—to determine COI the consideration to be exchanged for the proprietary interests in the target corporation pursuant to a contract to effect the reorganization is valued on the last business day before the first date the contract is binding (the “signing date”). The 2007 Regulations continue to apply the signing date rule but modified the 2005 Regulations. The following discussion provides an overview of the current regulations.

The signing date rule applies when a binding contract provides for fixed consideration. A binding contract is an instrument enforceable under applicable law against the parties to the instrument. The presence of a condition outside the control of the parties (including, e.g., regulatory agency approval) does not prevent an instrument from being a binding contract. Further, the fact that insubstantial terms remain to be negotiated by the parties to the contract, or that customary conditions remain to be satisfied, does not prevent an instrument from being a binding contract.

A contract provides for fixed consideration if it provides the number of shares of each class of stock of the issuing corporation, the amount of money, and the other property (identified either by value or by specific description, if any), to be exchanged for all the proprietary interests in the target corporation or to be exchanged for each proprietary interest in the target corporation. If the fixed consideration includes other property that is identified by value, that specified value is used in determining whether continuity is satisfied. If a contract does not provide for fixed consideration, the signing date rule does not apply.

The 2007 Regulations narrowed the fixed consideration definition by excluding contracts that provide only the percentage of the stock of the target corporation that will be exchanged for stock in the issuing corporation. This had been allowed in the 2005 Regulations.

Certain transactions that allow for shareholder elections are treated as providing for fixed consideration—regardless of whether the agreement specifies the maximum amount of money or other property or the minimum amount of issuing corporation stock to be exchanged in the transaction—if such elections are based on the value of the issuing corporation’s stock on the signing date. This rule applies when the target corporation shareholders may elect to receive issuing corporation stock in exchange for their target corporation stock at an exchange rate based on the value of the issuing corporation stock on the signing date. For example, assume the issuing corporation stock has a value of $1 per share on the signing date and the agreement provides that the target corporation shareholders may exchange each share of target corporation stock for either $1 or issuing corporation stock (based on the signing date value). In this situation, the target corporation shareholders that choose to exchange their target stock for issuing stock are subject to the economic fortunes of the issuing corporation with respect to such stock as of the signing date.

The 2007 Regulations generally provide that a modification of a contract results in a new signing date, but there are exceptions to this general rule. The exceptions apply both in cases when continuity would be preserved and in cases when it would not be preserved.

The 2007 Regulations provide that, generally, a contract that otherwise qualifies as providing for fixed consideration will be treated as providing for fixed consideration even if it provides for contingent adjustments to the consideration, and regardless of whether the transaction would have satisfied COI in the absence of any contingent adjustments. However, if the terms of the contingent adjustments potentially prevent the target corporation shareholders from being subject to the economic fortunes of the issuing corporation as of the signing date, the contract will not be treated as providing for fixed consideration. Accordingly, the 2007 Regulations provide that a contract will not be treated as providing for fixed consideration if it provides for contingent adjustments to the consideration that prevent (to any extent) the target shareholders from being subject to the economic benefits and burdens of ownership of the issuing corporation as of the signing date. For example, a contract will not be treated as providing for fixed consideration if it provides for contingent adjustments in the event that the value of the stock of the issuing corporation increases or decreases after the signing date.

A customary antidilution clause will not prevent a contract from being treated as providing for fixed consideration. If the issuing corporation’s capital structure is altered and the number of shares of the issuing corporation to be issued to the target corporation shareholders is altered under a customary antidilution clause, the signing date value of the issuing corporation’s shares must be adjusted to take this alteration into account. However, the absence of such a clause will prevent a contract from being treated as providing for fixed consideration if the issuing corporation alters its capital structure between the first date there is an otherwise binding contract to effect the transaction and the effective date of the transaction in a manner that materially alters the economic arrangement of the parties to the binding contract.

There are a few other rules to note in the 2007 Regulations. The possibility that some shareholders may exercise dissenters’ rights and receive consideration other than that provided for in the binding contract will not prevent the contract from being treated as providing for fixed consideration. The fact that money may be paid in lieu of issuing fractional shares will not prevent a contract from being treated as providing for fixed consideration. For purposes of valuing stock for COI purposes, any class of stock, securities, or indebtedness that the issuing corporation issues to the target corporation shareholders pursuant to the potential reorganization and that does not exist before the first date there is a binding contract to effect the potential reorganization is deemed to have been issued on the last business day before the first date there is a binding contract to effect the potential reorganization.

The 2007 Regulations went into effect on March 20, 2007, and apply to transactions occurring pursuant to a binding contract entered into after September 16, 2005. The 2007 Regulations provide transitional relief for certain transactions occurring pursuant to a binding contract entered into after September 16, 2005, and on or before March 20, 2007. Parties to transactions within the scope of the transitional relief may elect to apply the 2005 Regulations on a consistent basis.

(e) Control

Control is another concept that is important to the reorganization provisions. For example, an acquiring corporation must obtain “control” of the target corporation in a stock-for-stock B reorganization. In addition, where the reorganization provisions permit stock of the acquiring corporation’s parent (rather than the acquiring corporation itself) to be used to effect the reorganization, the parent must “control” the acquiring corporation. Finally, after certain reorganizations, assets may be transferred to a corporation “controlled” by the acquiring corporation. Control for all these purposes is defined as 80 percent of the voting stock and 80 percent of each class of nonvoting stock.60 Unlike the definition of control in the context of the liquidation of a subsidiary into its parent,61 or the determination of entities entitled to file consolidated returns,62 the control definition just discussed is not based on value. A corporation is permitted to file a consolidated return with a subsidiary if it owns 80 percent of the voting stock and 80 percent of the value of the stock of the subsidiary, notwithstanding its failure to own any stock of a class of nonvoting preferred.63 However, the failure to own at least 80 percent of a class of nonvoting preferred stock will preclude satisfying the definition of control for purposes of the reorganization requirements just discussed. Furthermore, the control must be direct, not through subsidiaries.64

Control tests are not always mechanically applied. In Alumax v. Commissioner,65 the Eleventh Circuit Court of Appeals rejected a perfunctory application of the I.R.C. section 1504(a)(2) test, because restrictions on the ability of directors to carry out all of their management functions diluted the effectiveness of both the directors’ vote and the shareholders’ vote.66 Although Alumax involved the taxpayers’ ability to file a consolidated return, its principles should be equally applicable to the I.R.C. section 368(c) control requirement in B and D reorganizations.

(f) Contingent and Escrowed Shares

Tax-free reorganizations generally require the issuance of stock. This requirement raises questions about the proper treatment of transactions in which stock will or may be issued after the reorganization. Generally, debt, warrants, or options, which either will or may result in future stock issuances, do not count as stock currently issued for purposes of satisfying COI.67 The IRS has, however, provided guidelines addressing the issuance of contingent shares or escrowed shares in tax-free reorganizations in Revenue Procedure (Rev. Proc.) 84-42.68 Shares that are unissued, but subject to issuance in the future, are designated “contingent shares.” The guidelines for contingent stock are generally as follows:

- All the stock will be issued within five years from the date of the reorganization.

- There is a valid business reason for not issuing all the stock immediately, such as difficulty in determining the value of one or both of the corporations involved in the transactions.

- The maximum number of shares that may be issued in the exchange is stated.

- At least 50 percent of the maximum number of shares of each class of stock that may be issued is issued in the initial transaction.

- The right to receive stock is either nonassignable by its terms or, if evidenced by negotiable certificates, then not readily marketable.

- Such right can give rise to the receipt only of additional stock of the corporation making the underlying distribution.

- Such stock issuance will not be triggered by an event the occurrence or nonoccurrence of which is within the control of shareholders.

- Such stock issuance will not be triggered by the payment of additional tax or reduction in tax paid as a result of an IRS audit.

- The method for calculating the additional stock to be issued is objective and readily ascertainable.

Rev. Proc. 84-42 provides a similar set of guidelines with respect to stock or property issued in a reorganization that is put in escrow under an agreement that directs an escrow agent to either release the stock to the acquiring corporation’s shareholders if certain conditions are satisfied or return the stock to the target corporation. The tax consequences resulting from the return of the escrowed shares will depend on the terms of the deal. If the number of shares that are returned was based on their initial negotiated value and the taxpayer had no right to substitute other property for the escrowed stock in the event of a repossession, then no gain or loss will be recognized to the beneficial owners.69 If, however, the number of shares of escrowed stock returned is based on the fair market value of the stock on the date of the return from escrow, then gain or loss will be realized to the beneficial owner in an amount equal to the difference between the fair market value and the basis of such stock at the time of the return.70

For many years, it appeared that if the Rev. Proc. 84-42 guidelines were followed, COI generally would have been satisfied.71 However, the signing date regulations should be consulted after their effective date, as discussed in § 5.2(d)(i) of this volume.

(g) Tax Treatment: Operative Provisions

The language of I.R.C. section 368 does not provide for tax-free treatment; rather, it defines the types of reorganizations that qualify for tax-free treatment if the judicial and regulatory standards (i.e., business purpose, COI, COBE) are satisfied. Other provisions of the I.R.C. (“operative provisions”) furnish the tax treatment for reorganizations. The tax consequences of a reorganization are generally as discussed next.72 The target corporation will recognize no gain or loss on the transfer of its assets to the acquiring corporation.73 Similarly, the target corporation will not recognize gain or loss on the distribution of acquiring stock or other assets (received in exchange for its assets) to its shareholders or creditors.74 The acquiring corporation will recognize no gain or loss on its receipt of the assets of the target corporation, its basis in those assets will be the same as the basis the target corporation had in the assets, and the holding period of the assets will include the period during which the target corporation held the assets.75 Similarly, the shareholders of the target corporation will recognize no gain or loss when they exchange their stock in the target corporation for stock in the acquiring corporation,76 and such stock will generally have the same basis as the surrendered stock of the target corporation. The holding period of the stock will include the time during which the shareholders held the stock of the target corporation.77

The same nonrecognition, substituted basis, and tacked holding period rules will apply to securities (generally long-term debt78) of the acquiring corporation79 received in exchange for target securities.

If a target corporation shareholder receives boot (property other than stock of the acquiring corporation or stock of the parent of the acquiring corporation in certain reorganizations), the shareholder may recognize gain or dividend income but not loss.80 In addition, if the principal amount of securities received in a reorganization exceeds the principal amount of the target securities exchanged therefor, the fair market value of the excess principal is boot.81

Preferred stock did not constitute boot until the Taxpayer Relief Act of 1997 modified various incorporation and reorganization I.R.C. provisions to treat certain preferred stock (“nonqualified preferred stock”) as boot.82 With specified exceptions, nonqualified preferred stock is stock that is limited and preferred as to dividends, does not participate in corporate growth to any significant extent, and has a feature that would cause it to be redeemed within 20 years from the date of issuance.83 In the context of a reorganization, nonqualified preferred stock received in exchange for stock (other than nonqualified preferred stock) is boot subject to gain recognition.84

The status of nonqualified preferred stock as boot is limited to gain recognition; nonqualified preferred stock is treated as stock for other purposes.

Prospective regulations may treat preferred stock as something other than stock for other purposes, such as COI and the control requirement. Until such regulations are issued, however, preferred stock will continue to be treated as stock for purposes of other provisions of the I.R.C.85

Thus, for example, in the context of an ordinary type A reorganization, if 70 percent of the consideration is nonqualified preferred stock and the remaining 30 percent is voting common stock, COI will be satisfied. In other words, the statutory amendment, by itself, does nothing to change the characterization of the preferred stock for purposes of evaluating COI. The preferred stock is disqualified only for purposes of determining the amount of boot received in the reorganization. Thus, in this example, tax-free treatment is preserved at the corporate level and at the shareholder level, except to the extent the shareholders receive boot.86

In January 1998, the IRS and the Treasury finalized regulations that treat certain corporate rights to acquire stock as securities with a zero principal amount in the context of an I.R.C. section 368 reorganization.87 These regulations provide nonrecognition treatment for a target shareholder that receives rights to acquire stock in the acquiring corporation in a transaction that otherwise qualifies as a tax-free reorganization, provided the shareholder also receives stock of the acquiring corporation.

These final regulations also clarify that I.R.C. section 354 (the provision that provides tax-free treatment at the shareholder level in an I.R.C. section 368 corporate reorganization) does not apply to a shareholder’s receipt of rights to acquire stock if the shareholder receives only such rights and no stock of the acquiring corporation. Thus, if a shareholder receives solely boot (and no acquiring corporation stock or acquiring parent’s stock) in a reorganization, the transaction could be treated as a redemption or potentially a liquidation.88

The IRS and Treasury also issued regulations89 to coordinate the finalization of the warrant regulations with enactment of the nonqualified preferred stock rules discussed. The regulations provide that a right to acquire nonqualified preferred stock received in exchange for stock other than nonqualified preferred stock or for a right to acquire stock other than nonqualified preferred stock will also generally not be treated as stock or a security and may therefore give rise to shareholder gain or dividend income in the context of an I.R.C. section 368 reorganization.90

(h) Substance over Form and Step Transaction Doctrines

The IRS may apply the Substance over Form and Step Transaction doctrines to disregard the separate steps of an integrated transaction and recharacterize the transaction for federal income tax purposes in order to conform the tax consequences of the transaction with its true substance. These doctrines may be applied to treat or otherwise recast what appears to be a tax-free transaction into a taxable transaction,91 or what appears to be a taxable transaction into a tax-free transaction,92 or to transform one type of tax-free transaction into a different type of tax-free transaction.93 The proper application (or nonapplication) of the Substance over Form and Step Transaction doctrines has been the focus of many cases, IRS pronouncements, and articles and a thorough discussion of this topic is beyond the scope of this treatise. Suffice it to say, the potential application of the Substance over Form or Step Transaction principles should be carefully analyzed when determining the tax consequences of any multistep transaction, as things are not always what they appear to be.

One important development in this area is Treas. Reg. section 1.368-2(k). If the requirements of this provision are satisfied, a post-reorganization distribution or other transfer of stock or assets will neither disqualify an otherwise qualifying tax-free reorganization nor cause it to be recharacterized.

§ 5.3 OVERVIEW OF SPECIFIC TAX-FREE REORGANIZATIONS UNDER SECTION 368

The remainder of this chapter briefly surveys the types of transactions that qualify as acquisitive tax-free reorganizations, focusing first on asset acquisitions, including A mergers, C reorganizations, forward triangular mergers, and D reorganizations; second on stock acquisitions, including B reorganizations and reverse triangular mergers; and third on single-entity reorganizations, including E and F reorganizations. Next, this chapter considers divisive reorganizations (I.R.C. section 355 and D/355 transactions). Finally, the chapter discusses insolvency reorganizations, including G (bankruptcy) reorganizations.

§ 5.4 ACQUISITIVE ASSET REORGANIZATIONS

(a) A Reorganization: Merger or Consolidation

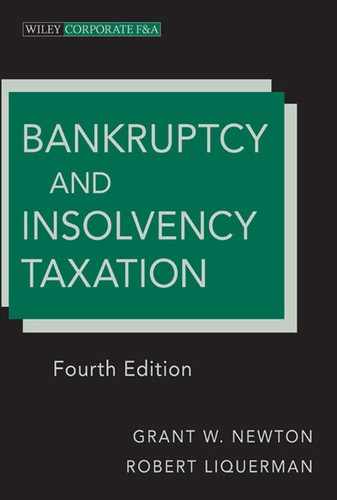

I.R.C. section 368(a)(1)(A) provides that one form of reorganization is a statutory merger or consolidation (an A reorganization). The Treasury Regulations generally require that the transaction be effected pursuant to a statute or statutes necessary to effect the merger or consolidation if certain other requirements are satisfied.94 A typical A merger is depicted in Exhibit 5.1. As described in greater detail in the ensuing subsections, the transfer of assets depicted in the exhibit could also qualify as a C reorganization, provided the Y stock is voting stock; as a D, provided the X shareholders are in control of Y after the transaction; and as a G, provided the transfer is pursuant to title 11 or a similar case.

Exhibit 5.1 Asset Acquisitions A, C, D, and G

Although they are similar, a merger and a consolidation are not the same. In a merger, the acquiring corporation is in existence prior to the transaction, and it will survive. If Corporation X and Corporation Y merge, with Corporation X as the target, upon the effective date of the merger, the separate existence of Corporation X will cease. Corporation Y will acquire all Corporation X’s assets, assume all Corporation X’s liabilities, and continue to operate the business of Corporation X (or use a significant portion of Corporation X’s assets in its own business). A consolidation, however, is a transaction in which Corporation X and Corporation Y consolidate to form a new corporation, Corporation Z. Corporation Z acquires all the assets of both Corporation X and Corporation Y, assumes their liabilities, and continues their businesses (or uses a significant portion of their assets in its business). The difference is that the “survivor” of a consolidation had no existence prior to the reorganization and is a product of the reorganization. The survivor in a consolidation has no ability to carry back post-acquisition losses to a preacquisition year; the survivor in a merger can carry back a postmerger loss to its own premerger year.95

Otherwise, the tax consequences of both transactions are the same. Because mergers are significantly more common than consolidations, the remaining discussion of I.R.C. section 368(a)(1)(A) refers to mergers.

A transaction must be more than a statutory merger to qualify as a reorganization. As discussed, it must have a bona fide business purpose and must satisfy COBE and COI. There are many mergers for cash and/or notes that qualify as statutory mergers under state law but are not considered tax-free corporate reorganizations. They merely result in a corporate- and shareholder-level tax, just as if the target corporation had sold its assets and liquidated.96 In addition, an A reorganization will not be disqualified for lack of COBE if the acquiring corporation transfers target’s assets to a subsidiary corporation or a partnership within the parameters described in § 5.2(c).

In addition, some state law mergers in which the consideration is stock (and not cash or notes) will also fail to qualify as tax-free A reorganizations. For example, the IRS has ruled that certain state law mergers that resemble corporate divisions (rather than amalgamations) cannot qualify as A reorganizations.97 Also, recent proposed and temporary regulations follow the logic of this ruling and deny A reorganization treatment to some mergers involving disregarded entities. In general, the temporary and proposed regulations provide that the merger of a disregarded entity into a corporation does not qualify as an A reorganization but that the merger of a target corporation into a disregarded entity may qualify as an A reorganization.98

(b) C Reorganization

(i) Overview

I.R.C. section 368(a)(1)(C) describes two types of asset acquisitions that may qualify as reorganizations: C reorganizations and parenthetical C reorganizations. The latter is so named because it appears as a parenthetical clause in I.R.C. section 368(a)(1)(C). Section 368(a)(1)(C) reorganizations are often referred to as “practical mergers,” because they were instituted at a time when certain state-law mergers were unavailable in some states. C reorganizations do, however, impose a number of requirements not imposed by A mergers. Foremost among these is the “solely for voting stock” test, described next.

A C reorganization is the acquisition by one corporation, solely in exchange for its voting stock, of substantially all the assets of the target corporation. The acquiring corporation may use as consideration stock of a corporation that controls it, yielding a parenthetical C reorganization. In addition, in either type of C reorganization the acquiring corporation may transfer target’s assets to a subsidiary corporation or a partnership within the parameters described in § 5.2(c).

C reorganizations share the “solely for voting stock” requirement with B reorganizations. In the latter, this requirement is strictly interpreted. In C reorganizations, however, “solely” does not mean solely. First, I.R.C. section 368(a)(1)(C) specifically provides that the assumption by the acquiring corporation of the liabilities of the target corporation will not, by itself, violate the “solely for” test. Second, I.R.C. section 368(a)(2)(B) provides that, if the acquiring corporation acquires 80 percent of the fair market value of the target corporation’s assets solely for voting stock, then nonstock consideration may be used in the exchange without disqualifying the reorganization. (This is commonly referred to as the boot relaxation rule.)

If such other consideration is used, however, then all assumed liabilities are considered to be money paid for the assets.99 Even $1 of cash invokes I.R.C. section 368(a)(2)(B), and if the sum of the cash given, other property transferred, and liabilities assumed by the acquiring corporation exceeds 20 percent of the value of the target corporation before the transaction, it will not be a valid C reorganization. Thus, in general, only corporations with very little debt can be acquired in a valid C, if the package of consideration includes property other than voting stock. As a result, the vast majority of C reorganizations are accomplished solely for voting stock and the assumption of the liabilities of the target corporation.

A 1999 regulation also addresses the “solely for voting stock” requirement in a C reorganization.100 That regulation generally provides that an acquiring corporation’s preexisting ownership of a portion of the shares of a target corporation will not, in and of itself, prevent the solely-for-voting-stock requirement of a C reorganization from being satisfied. This regulation reverses the IRS’s long-standing position (which was confirmed by the Tax Court in Bausch & Lomb Optical Co. v. Commissioner101) that an acquiring corporation’s acquisition of the assets of a partially controlled subsidiary does not qualify as a C reorganization.102

(ii) “Substantially All”

A C reorganization requires the acquisition of “substantially all” of the properties (or assets) of the target corporation. Few concepts have proven as difficult to define. The IRS provides a safe harbor rule that “substantially all” means at least 90 percent of the fair market value of the net assets and at least 70 percent of the fair market value of the gross assets of the target corporation.103 Courts, however, have accepted significantly less than this amount in satisfaction of the requirement. In Smothers v. United States,104 for example, a transfer of approximately 15 percent of the corporation’s net assets qualified.

The safe harbor test makes no distinction between operating assets and investments. Although the question is far from settled, the focus of the inquiry seems to be on operating assets.105 Dispositions of assets by the target prior to the reorganization may be considered in determining whether substantially all of the target assets have been acquired. Payments of reorganization expenses, payments to dissenting shareholders, redemptions, and partial liquidations are among the transactions that result in a diminution of the target assets and may thus have an impact on the substantially all test.106 The substantially all test is quantitative, not qualitative. Thus, the substitution of one group of assets for other assets will not affect this test, although it could have an impact on the COBE requirement.107

(iii) Liquidation

Prior to 1984, there was no requirement in a C reorganization that the target corporation dissolve following the transfer.108 Since 1984, the target corporation must distribute all of the stock, securities, and other property received in the reorganization, as well as its other properties.109 The Commissioner is permitted to waive this requirement.110 One possible condition to this waiver is that the target corporation and its shareholders treat any retained assets as having been distributed and recontributed to the capital of a new corporation.111 The waiver is likely to be sought if the target corporation possesses a valuable charter or other attributes inhering to the corporate shell, which would be lost upon dissolution.

A 1989 Revenue Procedure112 provides that the IRS will issue C reorganization rulings notwithstanding the target corporation’s failure to satisfy this dissolution requirement, if the following representations are made:

- The target will retain only its charter and those assets necessary to satisfy state law minimum capital requirements.

- Substantially all the assets will be transferred after taking into consideration the value of the retained assets.

- The purpose of the transaction is to isolate the target’s charter for resale to an unrelated purchaser.

- As soon as practical, but in no event later than 12 months after substantially all the assets are transferred, the target’s stock will be sold.

If relief is provided under Rev. Proc. 89-50, for tax purposes, the charter and retained capital will be treated as distributed and then reincorporated into a new target corporation. This revenue procedure also applies to acquisitive D reorganizations, which also must satisfy a dissolution requirement.113

(iv) Distribution to Creditors

As a result of the Tax Reform Act of 1986, a target corporation will have satisfied the liquidation requirement even if the shareholders receive none of the acquiring corporation’s stock in the reorganization.114 Distributions to creditors may be sufficient to comply with the liquidation standard and satisfy COI. For this reason, a C reorganization, in certain circumstances (e.g., when the corporation is not under title 11) may be an alternative to the G reorganization for an insolvent corporation. A fuller discussion of insolvency reorganizations outside of bankruptcy is provided in § 5.8(a).

(c) Triangular Asset Acquisitions

Triangular reorganizations, as the name implies, involve three corporations: a parent corporation, a subsidiary corporation controlled by the parent corporation, and a target corporation whose stock or assets are acquired in the reorganization.

The I.R.C. specifically provides for four types of triangular reorganizations, two that involve statutory mergers (the forward triangular merger, described in I.R.C. section 368(a)(2)(D), and the reverse triangular merger, described in I.R.C. section 368(a)(2)(E)), and two others (the parenthetical B and the parenthetical C) that do not. In each of these transactions, a corporation (the subsidiary) acquires the stock or assets of the target corporation (target) in exchange for stock of a corporation in control of the acquiring corporation (parent). Thus, the parent, subsidiary, and target form the three sides of the triangle. Triangular asset reorganizations are discussed here, and triangular stock acquisitions are discussed in § 5.5(b).

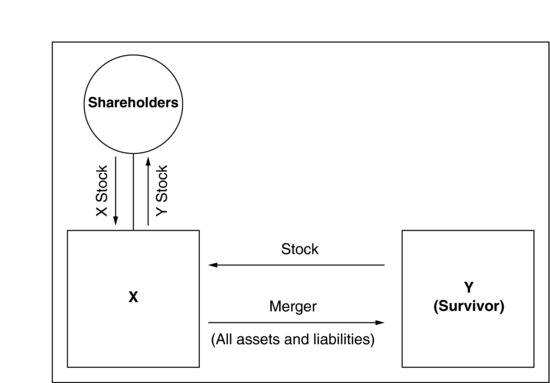

Exhibit 5.2 shows the form of a triangular asset acquisition under I.R.C. section 368(a)(2)(D) or section 368(a)(1)(C) (parenthetical clause). Provided the parent’s stock is voting stock, this transaction qualifies as a parenthetical C as well.115 Again, although there is no requirement in a C that the assets move via a merger, there is no prohibition either.

Exhibit 5.2 Forward Triangular Merger and Parenthetical C

In a forward triangular merger, the subsidiary can be a newly formed corporation established merely to effectuate the transaction or an existing corporation with substantial business assets. As a practical matter, about 90 percent of all forward triangular acquisitions involve newly established subsidiaries.

In a forward triangular merger, the target corporation is merged into the subsidiary with the subsidiary surviving. Unlike a straight A reorganization, the subsidiary must acquire substantially all of the assets of the target.116 However, no stock of the subsidiary may be issued in the transaction.117 Rather, stock of the parent, which must be in control of the subsidiary, is issued to the target in the exchange. Although only stock of the parent may be issued, it is permissible to use nonstock consideration (i.e., cash, parent debt, subsidiary debt, etc.) or to have either the parent or the subsidiary, or both, assume the liabilities of the target.118

Special basis rules apply to triangular reorganizations. In a forward triangular merger or triangular C reorganization, the parent corporation’s basis in its subsidiary stock is adjusted as if (1) parent acquired the target corporation assets that were acquired by the subsidiary (and parent assumed any liabilities which subsidiary assumed) directly from target in a transaction in which parent’s basis in target’s assets was determined under I.R.C. section 362, and then as if (2) parent transferred those assets (and liabilities) to subsidiary in a transaction in which parent’s basis in the subsidiary stock was determined under I.R.C. section 358.119 This is commonly referred to as the “over-the-top model.”

EXAMPLE 5.1

Facts: T has assets with a basis of $60 and a fair market value of $100 and no liabilities. P forms S with $10 (which S retains) and T merges into S in exchange for $100 worth of P stock.

Analysis: The merger qualifies as a forward triangular reorganization under I.R.C. section 368(a)(2)(A). P’s $10 of basis in the T stock is adjusted as if P acquired the T assets directly from T in the reorganization. Under I.R.C. section 362, T would have a $60 basis in the T assets. P is then treated as if it transferred the T assets to S. P’s $10 basis would be increased by $60 to $70 pursuant to I.R.C. section 358. ![]()

As with an A reorganization, a forward triangular merger is not disqualified if the acquiring corporation (subsidiary) transfers target’s assets to a corporation controlled by subsidiary.120 This concept has been expanded to include multiple drops and transfers to partnerships within the parameters described in § 5.2(c), above. Further, the subsidiary stock may be transferred by parent to another subsidiary controlled by parent following the forward triangular merger.121

(d) Acquisitive D Reorganization

(i) Overview

I.R.C. section 368(a)(1)(D) provides that a reorganization includes a transfer by a corporation of all or part of its assets to another corporation if, immediately after the transfer, the transferor corporation or one or more of its shareholders (or a combination thereof) are in control of the transferee corporation; but only if the stock of the transferee corporation is distributed pursuant to I.R.C. section 354, 355, or 356. (See Exhibit 5.1 for an example of a D reorganization.) Because the focus of the reorganization provisions here is on acquisitive transactions, the I.R.C. section 355 ramifications of a divisive D reorganization (spin-off, split-off, and split-up) are discussed separately in § 5.7.

(ii) “Substantially All”

In a D reorganization, the target corporation must transfer substantially all of its assets to the acquiring corporation.122 The same rules (including rulings and case law) that define “substantially all” for purposes of a C reorganization define substantially all for purposes of a D reorganization. Most of the cases in this area involve efforts by the government to establish a D reorganization when the taxpayer is seeking to avoid reorganization treatment and obtain the more favorable treatment afforded liquidations under pre-1986 tax law.

The transfer of the assets from target to acquiring corporation will meet the substantially all definition even if that transfer is small, indirect, or convoluted.123

(iii) Distribution of Stock

To qualify as an acquisitive D reorganization, the stock of the acquiring corporation received by the target corporation in exchange for its assets must be distributed to the shareholders of the target corporation in a transaction qualifying under I.R.C. section 354 or 356. I.R.C. section 354(b)(1)(A) provides that the acquiring corporation must acquire “substantially all” of the assets of the target corporation, and I.R.C. section 354(b)(1)(B) provides that the target corporation must dissolve and distribute its remaining properties to its shareholders. Failing either of the above, the transfer of assets will not qualify as a D reorganization, because I.R.C. section 354 will not apply. I.R.C. section 356 applies only when, in exchange for its assets, the target corporation receives property other than stock or securities of the acquiring corporation. As provided in I.R.C. section 356(a)(1)(A), I.R.C. section 356 will apply only if, but for the receipt of the other property, I.R.C. section 354 would have applied. Again, it will be necessary to comply with the requirement to transfer substantially all of the assets and to dissolve the target corporation.

Prior to 2006, there was a long-standing question as to whether and in what circumstances the distribution requirement under I.R.C. sections 368(a)(1)(D) and 354(b)(1)(B) could be deemed satisfied in the absence of an actual issuance of stock or securities (e.g., if there are common shareholder interests that would render the distribution of stock a “meaningless gesture”).124 In December 2006, the Treasury Department released temporary and proposed regulations, which provided that there could be a deemed issuance of stock in certain situations.125 These regulations were finalized with certain modifications and clarifications in December 2009.126 The final Treasury Regulations provide that a transaction that otherwise qualifies as an acquisitive D reorganization will be treated as satisfying the requirement that the transferor distribute stock or securities, even if there is no actual issuance of stock or securities, if the same person or persons own, directly or indirectly, all of the stock of the transferor (i.e., target) and transferee (i.e., acquiring) corporations in identical proportions.127 To the extent no consideration is received or the value of the consideration received in the transaction is less than the fair market value of the target corporation’s assets, the acquiring corporation will be deemed to issue stock with a value equal to the difference in value between the corporation’s assets and the consideration actually received in the transaction.128 To the extent the value of the consideration received in the transaction is equal to the fair market value of the target corporation’s assets, the acquiring corporation will be deemed to issue a nominal share of its stock along with the boot.129

Thus, if parent corporation owns all of the stock of both the target corporation and acquiring corporation and target (1) sells all of its assets to acquiring for cash and then (2) liquidates, distributing the cash to its shareholder, the I.R.C. section 354 distribution requirement will be deemed to be satisfied and the transaction will be treated as a D reorganization. The import of this is that the nonstock consideration (i.e., boot) that is distributed to the shareholder may be treated as a boot dividend.130

The IRS has historically taken the position that an actual liquidating distribution of assets by a corporation (X) followed by a transfer (reincorporation) of its assets by the shareholders to another commonly owned corporation (Y) may similarly be recast and treated as a D reorganization of X into Y. However, if X merges upstream into its parent corporation, there is long-standing precedent that the form of the transaction should be respected and the transaction should be treated as an upstream A reorganization of X into parent corporation followed by an I.R.C. section 368(a)(2)(C) transfer of assets by parent corporation to Y.131 The IRS has shown signs of extending this practice to transactions that are not accomplished by means of an upstream merger.132

(iv) Control

In an acquisitive D reorganization, the transferor corporation or its shareholders must be in control of the acquiring corporation. Solely for this purpose, control means 50 percent of the vote or value. Attribution rules are also used to determine control. Thus, if X corporation (wholly owned by P corporation) transfers substantially all its assets to Y corporation (wholly owned by Q corporation), the transaction will qualify as a D reorganization if P is owned by individual M and Q is owned by M’s father.133

(v) Section 357(c)

(A) Current Law

Many A reorganizations, as well as reorganizations that would otherwise qualify as C reorganizations, are also D reorganizations. Before 2004, this overlap could result in the imposition of tax if care was not taken in structuring the transaction. In an overlap between an A and a D reorganization, tax was imposed if the liabilities of the target corporation assumed by the acquiring corporation exceeded the basis of the assets transferred. The tax was imposed by I.R.C. section 357(c). This section does not apply to A reorganizations, but it did apply to all D reorganizations. The IRS had determined that, in certain overlap situations, I.R.C. section 357(c) would apply.134

The American Jobs Creation Act of 2004 changed this rule for acquisitive D reorganizations. In general, acquisitive D reorganizations are no longer subject to I.R.C. section 357(c).135 I.R.C. section 357(c) still applies to I.R.C. section 351 transactions, divisive D reorganizations, and I.R.C. section 355 distributions pursuant to a plan of reorganization within the meaning of I.R.C. section 368(a)(1)(D). However, it was unclear whether a D reorganization that overlaps with an I.R.C. section 351 transaction remained subject to I.R.C. section 357(c) because the transaction is treated as an I.R.C. section 351 transaction.

In Rev. Rul. 2007-8,136 the IRS ruled that I.R.C. section 357(c)(1) no longer applies to acquisitive asset reorganizations (A, C, D, or G reorganizations) that also qualify as section 351 exchanges, in light of changes made under the American Jobs Creation Act of 2004.

(B) Prior Law

Prior to the statutory amendments discussed above, I.R.C. section 357(c) required the transferor of the property in an I.R.C. section 351 exchange137 or in a D reorganization to recognize gain to the extent that the “assumed” liabilities plus the liabilities to which the transferred property was “subject,” exceeded the transferor’s basis in the transferred property. Following the transfer, the basis of the property in the hands of the controlled corporation would equal the transferor’s basis in such property, increased by the amount of gain recognized by the transferor, including I.R.C. section 357(c) gain.

The IRS had won several cases that held that the I.R.C. section 357(c) “subject to” language could result in the recognition of gain even if there was no economic gain.138 When taxpayers began to use these otherwise adverse precedents as a sword, Congress got worried. For example, I.R.C. section 357(c) gain could ostensibly be used by a foreign transferor that was not subject to United States tax to achieve for a domestic transferor corporation basis in assets in excess of their value.

Congress therefore amended I.R.C. sections 357(c), 357(d), and 362(d) to eliminate the reference to “liabilities to which property is subject” and to provide a framework for how to deal with liabilities.139 In doing so, the distinction between the assumption of a liability and the acquisition of an asset subject to a liability was generally eliminated. Under the amendment, a recourse liability (or any portion thereof) is treated as having been assumed if, as determined on the basis of all facts and circumstances, the transferee has agreed to, and is expected to satisfy the liability or portion thereof (whether or not the transferor has been relieved of the liability). Thus, where more than one person agrees to satisfy a liability or portion thereof, only one would be expected to satisfy such liability or portion thereof. A nonrecourse liability (or any portion thereof) is treated as having been assumed by the transferee of any asset that is subject to the liability. This amount is reduced, however, if an owner of other assets subject to the same nonrecourse liability agrees with the transferee to, and is expected to, satisfy the liability. This exception applies only to the extent of the fair market value of the other assets that secure the liabilities.140 In determining whether any person has agreed to and is expected to satisfy a liability, all facts and circumstances are to be considered.141

In addition, the basis of the transferred property may generally not be increased due to I.R.C. section 357(c) gain in excess of the fair market value of the property. If gain is recognized to the transferor as the result of an assumption by a corporation of a nonrecourse liability that also is secured by any assets not transferred to the corporation, and if no person is subject to federal income tax on such gain, then for purposes of determining the basis of assets transferred, the amount of gain treated as recognized as a result of the assumption is determined as if the liability assumed by the transferee equaled the transferee’s ratable portion of the liability, based on the relative fair market values of all assets subject to the nonrecourse liability.142

The Treasury Department has been granted authority to prescribe regulations to carry out the purposes of the provision. Although these amendments were enacted in 1999, 2000, and 2002, the provision is effective for transfers on or after October 19, 1998.

Two commonly controlled corporations that would otherwise have had an I.R.C. section 357(c) gain due to the overlap of the A and D reorganization provisions could easily avoid the problem by merging, or otherwise transferring their assets, in the opposite direction. For example, assume that P owns 60 percent of the stock of X and 100 percent of the stock of Y. X is otherwise solvent, but the liabilities of X exceed the basis of its assets. A transfer by X to Y of substantially all assets for stock of Y (representing 20 percent of the outstanding Y stock) will qualify as a reorganization but will cause X to recognize under I.R.C. section 357(c) a gain equal to the difference between the liabilities assumed over the basis of the assets. However, a merger of Y into X, in which Y transfers substantially all of its assets to X, will be tax free and will not result in an I.R.C. section 357(c) gain. The gain can be recognized only by a corporation that has excess liabilities and that transfers its assets.

It should also be noted that I.R.C. section 357(c) generally does not apply to transfers between members of a consolidated group, and did not apply even before its repeal with respect to acquisitive D reorganizations.143 This exception will not apply, however, to a transaction if the transferor or transferee becomes a nonmember as part of the same plan or arrangement.144

(vi) Other Issues

In addition to the I.R.C. section 357(c) tax problem, if the transaction in question is an overlap between a C and a D reorganization, then the target corporation may not be free to remain in existence, even on the limited basis permitted by the Tax Reform Act of 1984. The reason for this is that I.R.C. section 368(a)(2)(A) provides that if a transaction is described in I.R.C. sections 368(a)(1)(C) and (a)(1)(D), then it will be treated only as a D reorganization.145 As stated, in order to qualify as a D reorganization, the target corporation must dissolve. Failure to do so may cause the transaction to be treated as a fully taxable sale of assets. Notwithstanding this rule, the IRS has permitted insurance companies in D reorganizations to separate charters from operating assets in a manner similar to that permitted in C reorganizations.146

A final matter with respect to D reorganizations involves an issue concerning D reorganizations and I.R.C. section 368(a)(2)(C). As described, I.R.C. section 368(a)(2)(C) allows post-reorganization transfers to controlled corporations after an A, B, or C reorganization. As discussed in § 5.2(c), recent regulations have extended such transfers to corporations that are members of qualified groups and, in certain instances, to partnerships. I.R.C. section 368(a)(2)(C) does not include D reorganizations in the list of reorganizations that permit post-acquisition drops. In Rev. Rul. 2002-85,147 the IRS concluded that an acquiring corporation’s transfer of a target corporation’s assets to a subsidiary controlled by the acquiring corporation will not prevent a transaction from qualifying as a D reorganization.148

§ 5.5 STOCK ACQUISITIONS

In general, an acquiring corporation can acquire the stock (as opposed to the assets) of a target corporation in one of two ways: a B reorganization or an I.R.C. section 368(a)(1)(A)/(a)(2)(E) reverse triangular merger. The distinguishing feature of these two types of tax-free reorganizations is that in each, the target corporation survives.

(a) B Reorganization

(i) Overview

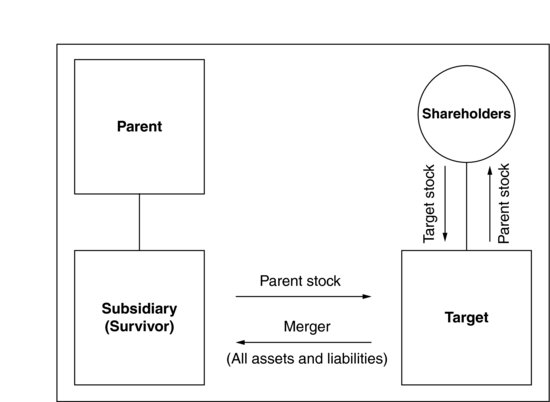

As with C reorganizations, discussed earlier, I.R.C. section 368(a)(1)(B) describes two types of stock acquisitions that may qualify as reorganizations: B reorganizations and parenthetical B reorganizations. The latter is so named because it appears as a parenthetical clause in I.R.C. section 368(a)(1)(B).149 Exhibit 5.3 presents diagrams of these two transactions. In a B reorganization, the acquiring corporation exchanges shares of its own voting stock for the stock of the corporation it wishes to acquire. In a parenthetical B reorganization, the acquiring corporation exchanges stock of a corporation that controls it (i.e., its parent) for the stock of the corporation it wishes to acquire.150 In either type of transaction, the consideration given to the target corporation’s shareholders must consist solely of voting stock and the acquiring corporation must be “in control” of the target corporation after the transaction. In addition, in either type of B reorganization, the stock of the target may be subsequently transferred by the acquiring corporation to a subsidiary or partnership within the parameters discussed in § 5.2(c).

Exhibit 5.3 Stock Acquisition B (top) and Parenthetical Stock Acquisition—Parenthetical B (bottom)

(ii) “Solely for Voting Stock”

The major issue in either type of B reorganization is whether the acquisition was accomplished “solely for voting stock.” In the context of a B reorganization, the “solely” requirement is strictly construed. The only exception is that cash may be paid for fractional share interests.151 The IRS has determined that warrants, options, or stock that is restricted from voting for five years will not satisfy the “solely for voting stock” requirement.152 Stock is considered voting stock, however, if it is restricted from voting because it is held by a subsidiary.153 Nonvoting stock that is convertible into voting stock is not considered voting stock until it is converted.154 Stock that gives its owner the right to participate in management through the election of corporate directors will generally satisfy the test.155 The “solely for voting stock” requirement is not violated if the target shareholders receive cash or other property (1) from the target corporation as a dividend or in redemption of stock prior to and as part of a B reorganization,156 or (2) from the acquiring corporation in exchange for a nonshareholder interest (i.e., a debenture, an employment agreement, a leasehold, or real property).157

In a B reorganization, the acquiring corporation cannot acquire “control” (i.e., I.R.C. section 368(c) control—80 percent vote and 80 percent each class of nonvoting stock) solely for voting stock of the target corporation and then acquire the remainder for cash or other consideration. The IRS has unequivocally denied reorganization status to such a transaction,158 and the courts have agreed.159 Moreover, the acquiring corporation cannot do indirectly through a subsidiary what it could not do directly. Thus, if P corporation acquires 90 percent of the stock of target corporation (T) solely for P voting stock, and S (a wholly owned subsidiary of P) acquires the balance of the T stock for cash, P’s acquisition cannot qualify as a B reorganization.160

The “solely for voting stock” requirement can also be violated in a number of subtle ways. The assumption of a shareholder liability161 (even pursuant to a merger concurrent with the B reorganization162), the complete liquidation of a wholly owned subsidiary corporation that holds target corporation stock needed to obtain control,163 and unreasonable payments to a shareholder-employee for compensation or a covenant-not-to-compete will all violate the solely for voting stock requirement.

An improvident purchase of target stock for cash in a prior period may preclude a later B reorganization. If the first step (cash purchase) is integrated with the later stock-for-stock exchange, the “solely for voting stock” requirement will be violated. If, however, the first step (cash purchase) is “old and cold,” then the later exchange should qualify as a B reorganization. Thus, a cash purchase by X corporation of 40 percent of T corporation four years ago would not preclude a B reorganization today, if X corporation acquires the remaining 60 percent solely for X’s voting stock. However, if the prior cash purchase was four months ago, the later 60 percent acquisition would probably not be a valid B. Prior cash purchases can, however, be “purged” by selling the cash-purchased stock in the open market and reacquiring it in exchange for voting stock.164

(iii) Control