CHAPTER SIX

Use of Net Operating Losses

§ 6.1 Introduction

§ 6.2 I.R.C. Section 381

(a) Introduction

(b) Qualifying Acquisitions

(i) Liquidation of Controlled Subsidiary

(ii) Reorganizations

(c) Tax Attributes

(d) Transfer of Net Operating Losses

(e) Limitations on Carryover of Net Operating Losses

§ 6.3 Restructuring under Prior I.R.C. Section 382

(a) Introduction

(b) Old I.R.C. Section 382(a)

(c) Old I.R.C. Section 382(b)

§ 6.4 Current I.R.C. Section 382

(a) Introduction

(b) Overview

(i) Section 382 Limitation

(ii) Value of the Loss Corporation

(A) Options

(iii) Long-Term Tax-Exempt Rate

(c) Allocation of Taxable Income for Midyear Ownership Changes

(d) Ownership Change

(i) Examples of Ownership Changes Involving Sales among Shareholders

(ii) Other Transactions Giving Rise to Ownership Changes

(iii) Examples of Ownership Changes Resulting from Other Transactions

(iv) Equity Structure Shift

(v) Purchases and Reorganizations Combined

(vi) Undoing a Section 382 Ownership Change

(vii) Bailout-Related Section 382 Relief

(A) Introduction

(B) Notice 2008-76: Fannie Mae/Freddie Mac

(C) Notice 2008-84: More-than-50-Percent Interest

(D) Notice 2008-83: Banks

(E) Notice 2008-100: Capital Purchase Program

(F) Notice 2009-14: Capital Purchase Program and Troubled Asset Relief Program

(G) Notice 2009-38: Treasury Acquisitions under Emergency Act Programs

(H) Notice 2010-2: Treasury Acquisitions and Dispositions under Emergency Act Programs

(I) New I.R.C. Section 382(n)

(e) Public Shareholders and the Segregation Rules

(i) Introduction

(ii) Segregation: Old Temporary Regulations

(iii) Segregation: Final Regulations

(A) Segregation Presumption—Cash Issuance Exception

(B) Small Issuance Exception

(iv) Segregation: Nuances

(v) Trading Involving Shareholders Who Are Not 5 Percent Shareholders

(vi) Options: Temporary Regulations

(vii) Options: Proposed Regulations

(viii) Options: Final Regulations

(A) Ownership Test

(B) Control Test

(C) Income Test

(D) Safe Harbors

(E) Subsequent Treatment of Options Treated as Exercised

(f) Reductions in the Section 382 Limitation

(i) Continuity of Business Enterprise

(ii) Nonbusiness Assets

(iii) Contributions to Capital

(A) Notice 2008-78

(B) Notice 2008-78 Rules

(C) Notice 2008-78 Safe Harbors

(D) Avoidance of Duplication with I.R.C. Section 382(l)(4)

(iv) Redemptions and Other Corporate Contractions

(v) Controlled Groups

(g) Special Rules

(i) Introduction

(ii) I.R.C. Section 382(l)(5)

(A) General Provisions

(B) Change of Ownership within Two Years

(C) Continuity of Business Enterprise

(iii) I.R.C. Section 382(l)(6)

(A) General Provisions

(B) Determining Value under I.R.C. Section 382(l)(6)

(C) Continuity of Business Enterprise

(iv) Comparison of I.R.C. Section 382(l)(5) and (l)(6)

(h) Built-In Gains and Losses

(i) In General

(ii) I.R.C. Section 382(h)(6)

(A) Legislative History

(B) IRS Rulings

(C) Notice 2003-65

(D) Prepaid Income

(iii) Treatment of Change Date Items

(A) Introduction

(B) Allocations on Ownership Change Date

(C) Relevant Rulings

(D) Observations

§ 6.5 I.R.C. Section 383: Carryovers Other than Net Operating Losses

(a) General Provisions

§ 6.6 I.R.C. Section 384

(a) Introduction

(b) Overview

(c) Applicable Acquisitions

(d) Built-In Gains

(e) Preacquisition Loss

§ 6.7 I.R.C. Section 269: Transactions to Evade or Avoid Tax

(a) Introduction

(i) Definition of Terms

(ii) Partial Allowance

(iii) Use of I.R.C. Section 269

(iv) Avoiding Tax by Using Operating Losses

(v) Ownership Changes in Bankruptcy

§ 6.8 Libson Shops Doctrine

(a) Overview

§ 6.9 Consolidated Return Regulations

(a) Introduction

(b) Consolidated Net Operating Loss Rules

(c) Application of I.R.C. Section 382 to Consolidated Groups

(i) Background

(ii) Overview

(d) Overlap Rule

(e) Unified Loss Rules

(i) Framework of the Unified Loss Rule

(ii) Basis Redetermination

(iii) Basis Reduction

(iv) Attribute Reduction

(v) Conclusion on Unified Loss Rule

(f) Application of I.R.C. Section 384 to Consolidated Groups

§ 6.1 INTRODUCTION

Internal Revenue Code (I.R.C.) section 172 provides for the carryback and carryover of net operating losses (NOLs). A corporation is, in most cases, allowed to carry over, for up to 20 years, NOLs sustained in a particular tax year that are not carried back to prior years.1 Beginning with tax years ending in 1976, taxpayers have been able to elect not to carry losses back.2 Prior to that time, losses had to be carried back to the three preceding tax years first; if all of the loss was not used against income in prior years, then it might be carried over.

The length of the carryback and carryover periods has varied over the years. The Taxpayer Relief Act of 1997 reduced the carryback period for NOLs from 3 years to 2 years and extended the carryover period from 15 years to 20 years.

The American Recovery and Reinvestment Tax Act of 2009 (ARRA) amended I.R.C. section 172 to allow an eligible small business (ESB) to elect to carryback NOLs incurred in tax years ending or beginning in 2008, for three, four, or five years, instead of the general two-year carryback. An ESB is generally a corporation, partnership, or sole proprietorship with average annual gross receipts of no more than $15 million for the three tax years ending with the NOL year. The same carryback period may apply to alternative minimum tax NOLs.3

Under the Worker, Homeownership, and Business Assistance Act of 2009 (WHBAA) certain taxpayers (including but not limited to ESBs) may elect to carry back an NOL generated in a tax year beginning or ending in 2008 or 2009 for a period of three, four, or five years (instead of the usual two-year carryback period). If an election is made under the WHBAA, such NOLs may not be subject to the alternative minimum tax (AMT) NOL limitations under I.R.C. section 56(d)(1)(A)(i). As described, the ARRA provides a similar election for ESBs with respect to a “2008 applicable NOL.”4

The extent to which the NOL can be preserved in bankruptcy and insolvency proceedings often depends on the manner in which the debt is restructured. The NOL is generally preserved if there is no change in ownership. The forgiveness of indebtedness generally does not affect the ability of the corporation to carry over prior NOLs.5 The loss carryover may, however, be reduced to the extent of the discharge of debt, as discussed in Chapter 2.6

Special problems may arise when the debt restructuring involves the use of another corporation. When a corporation acquires another corporation in certain tax-free asset acquisitions, I.R.C. section 381 permits the acquiring corporation to inherit and use the NOL carryovers of the acquired corporation. Both case law and other I.R.C. sections, however, may limit the use of such acquired carryovers. Even when no new corporation is involved, a number of transactions undertaken to restructure debt can change corporate ownership and trigger the application of I.R.C. provisions or judicial doctrines that limit a loss corporation’s ability to use its NOL carryovers.

The objective of this chapter is to discuss how the NOL can be preserved in an internal restructuring (generally a recapitalization under I.R.C. section 368(a)(1)(E)) or a

restructuring involving another corporation. The first part of the chapter, which briefly describes the provisions of I.R.C. section 381, is followed by a brief discussion of the provisions of I.R.C. section 382 that applied prior to the changes introduced by the Tax Reform Act of 1986. The balance of the chapter discusses the current I.R.C.: the section 382 provisions, the general limitation of section 382(b), the section 383 limitation on the use of credit carryovers, the section 384 limitation on the use of preacquisition losses to offset built-in gains, the bankruptcy exception of sections 382(l)(5) and (l)(6), and the tax avoidance provisions of section 269. The Libson Shops doctrine and the numerous special rules affecting losses in the consolidated return regulations are also discussed.

§ 6.2 I.R.C. SECTION 381

(a) Introduction

I.R.C. section 381 provides that, in certain types of acquisitions of assets of a corporation by another corporation, the acquiring corporation inherits some of the tax attributes of the acquired entity. NOL carryovers are one of the specified tax attributes.

(b) Qualifying Acquisitions

Only liquidations of controlled subsidiaries under I.R.C. section 332 and five types of tax-free reorganization under I.R.C. section 368(a) are subject to the tax attribute carryover rules of I.R.C. section 381(a).7

Unless some other statute provides otherwise, the NOL and other tax attributes of the acquiring corporation are not affected by the acquisition. As a general rule, if a loss is expected after a reorganization, the transaction should be structured so that the corporation with the greatest carryback potential (i.e., the corporation with the most income in prior periods for which a carryback of a subsequently generated NOL would result in the greatest refund) is the surviving corporation in the reorganization.

(i) Liquidation of Controlled Subsidiary

I.R.C. section 381(a)(1) permits the carryover of tax attributes, including NOLs, in a liquidation under I.R.C. section 332. The tax basis of the subsidiary’s assets also carries over to the parent.8 Section 332 applies to a “receipt by a corporation of property.” Thus, if the subsidiary is insolvent and its shareholders receive nothing in the liquidation, I.R.C. section 332 is not applicable because there is no receipt by a corporation of property distributed in complete liquidation of another corporation.9 I.R.C. section 332 treatment has even been denied where the preferred (but not the common) shareholders received property in the liquidation of a subsidiary.10 An insolvent subsidiary cannot be made solvent, prior to its liquidation, by having its parent cancel a debt due from the subsidiary.11 The liquidation of an insolvent subsidiary, however, entitles its parent to claim a bad debt deduction under I.R.C. section 166 and possibly a worthless stock deduction under I.R.C. section 165(g)(3).12

Three conditions must be met for a liquidation to qualify under I.R.C. section 332:

1. The parent corporation must own at least 80 percent of the total combined voting power of all classes of stock entitled to vote and at least 80 percent of the total value of all other classes of stock,13 excluding certain preferred stock.14 The 80 percent requirement can be met by an acquisition immediately before the liquidation,15 but it cannot be satisfied by a redemption before the liquidation.16 The intentional avoidance of I.R.C. section 332, in order to recognize a loss, by a sale of subsidiary stock to reduce the parent’s holdings below 80 percent is generally permitted.17

2. There must be a complete liquidation of all of the subsidiary’s assets in accordance with a plan of liquidation. I.R.C. section 332(b)(2) provides that a formal plan need not be adopted if there is a shareholders’ resolution authorizing the distribution of all the corporation’s assets in complete redemption of all stock. Thus, if there is an informal adoption of a plan of liquidation, I.R.C. section 332 may be satisfied if all property is transferred within a tax year.18

3. The plan of liquidation must provide for the transfer of all property within three years after the close of the tax year in which the first distribution is made.19 If the property is not distributed within this time frame, or if other provisions of I.R.C. section 332 subsequently prevent the distribution from qualifying, I.R.C. section 332 will not apply to any distribution.

(ii) Reorganizations

I.R.C. section 381(a)(2) requires the carryover of tax attributes, including NOLs, if property of one corporation is transferred pursuant to a plan of reorganization, solely for stock and securities in another corporation (I.R.C. section 361), provided the transfer is in connection with one of these tax-free reorganizations described in I.R.C. section 368(a)(1): A, C, D, F, or G.20 I.R.C. section 381 does not apply to B, divisive D, E, or divisive G reorganizations, nor does it apply to I.R.C. section 351 transfers.21 There is generally no carryover of attributes in these transactions.22

(c) Tax Attributes

As noted, I.R.C. section 381 provides for the carryover of tax attributes of the acquired corporation in certain tax-free reorganizations. Among the tax attributes discussed in I.R.C. section 381(c) are NOLs, earnings and profits, capital loss carryovers, investment credits, inventory and depreciation methods, and accounting methods. Because the I.R.C. lists the items that can be carried over, it might be assumed that unless an item is listed, it cannot be carried over. Legislative history, however, indicates that I.R.C. section 381 “is not intended to affect the carryover treatment of an item or tax attribute not specified in the section or the carryover treatment of items or tax attributes in corporate transactions not described in [I.R.C. section 381(a)].”23

(d) Transfer of Net Operating Losses

An inherited NOL must be used by the corporation that acquires the assets of a loss corporation. Thus, historically, if the acquired (loss) corporation in a C reorganization elected to continue some limited form of business and not liquidate, it would not use any prior NOL, because the loss would have passed to the acquiring corporation.24 This problem has been largely eviscerated for transactions occurring after 1984, however, because such transactions must generally include a liquidation of the acquired corporation in order to qualify as a C reorganization.25 Similarly, this problem should not arise in a G reorganization, because one of the G reorganization requirements is that the acquired corporation liquidate.

Treasury Regulation (Treas. Reg.) section 1.381(b)-1(b)(1) indicates that the NOL will generally pass to the acquiring corporation when the transfer is complete. The tax year of the transferor corporation will also generally end on this date. An alternate date—the date on which substantially all of the assets are transferred—may be used if the acquired corporation ceases operating except for those functions related to winding up its affairs.26 To use this alternate date, the acquired and acquiring corporations both must file written statements with the IRS.27

The NOL of the acquired corporation is carried to the first tax year of the acquiring corporation that ends after the date of the transfer. I.R.C. section 381 limits the amount of NOL that can be used in the year of transfer to the ratio of the remaining days until the end of the acquiring corporation’s tax year to 365 days. This provision is designed to prohibit the acquiring corporation from offsetting income earned prior to the acquisition against the acquired NOL. This formula must be used even though the income of the acquiring corporation may not be earned evenly throughout the year. Any NOL disallowed in the year of acquisition due to this restriction may be used in future years. The transfer of an NOL will usually result in the use of two years of the carryover period. The short tax year of the acquired corporation that ends on the date of transfer counts as one, and the tax year to which the NOL is transferred counts as another.28

An acquired NOL can generally be applied only against postacquisition income of the acquiring corporation. The acquiring corporation may, however, offset postacquisition losses against its own preacquisition income. Postacquisition operating losses of the acquiring corporation, however, generally may not be carried back against preacquisition income of the acquired corporation.29 The NOL carryback is allowed in a B and an E reorganization because there has been no movement of assets at the corporate level. A carryback is also permitted in an F reorganization, which may include an asset transfer, because this reorganization only involves a mere change of identity, form, or place of organization.

(e) Limitations on Carryover of Net Operating Losses

Although I.R.C. section 381 provides for the carryover of NOLs and other tax attributes, as noted in the introduction to this chapter, other I.R.C. sections and case law may limit carryover. Listed next is a summary of these limitations:

- Section 382 limitation. I.R.C. section 382(b) limits the amount of income that can be offset by loss carryovers each year to an amount equal to the value of the old loss corporation multiplied by the federal long-term tax-exempt rate.

- Section 383 limitation. I.R.C. section 383 limits the carryover of certain excess credits and net capital losses.

- Section 384 limitation. I.R.C. section 384 restricts a corporation from offsetting its built-in gains with preacquisition losses of another corporation.

- Bankruptcy exception. I.R.C. sections 382(l)(5) and (l)(6) contain special provisions for corporations in bankruptcy.

- Tax avoidance. I.R.C. section 269 may be used by the IRS to disallow any deduction, credit, or other allowance when the principal purpose of certain acquisitions is to avoid tax.

- Libson Shops doctrine. This doctrine prohibits the carryover of loss from the loss corporation to profits of different businesses.

- Corporate equity reduction transaction (CERT) rules. I.R.C. section 172(b)(1)(E) limits carrybacks of certain losses attributable to a CERT.

- Consolidated returns. The Treasury Regulations under I.R.C. section 1502 contain a number of restrictions on the use of NOLs.

§ 6.3 RESTRUCTURING UNDER PRIOR I.R.C. SECTION 382

(a) Introduction

Prior to the Tax Reform Act of 1986, restructuring of the debt and equity of a troubled corporation that did not involve a change in ownership generally did not affect the future use of NOLs. In selecting the nature of the restructuring, however, the debtor needed to be aware of areas where problems could develop. In particular, if the restructuring came under the provisions of I.R.C. section 382, NOL carryovers could be lost. In general, old I.R.C. section 382(a) eliminated the carryover if, through the purchase of stock, the 10 largest shareholders of the loss corporation increased their ownership by 50 percent or more within a two-year period, and the loss corporation’s old trade or business was abandoned. Old I.R.C. section 382(b) reduced the carryover if, in a tax-free reorganization, the shareholders of the old loss corporation received less than 20 percent of the stock of the reorganized corporation.

(b) Old I.R.C. Section 382(a)

Old I.R.C. section 382(a) applied only to purchases of stock from unrelated parties. Generally, stock was considered purchased if its basis in the hands of the acquirer was determined by reference to cost and if it was acquired from an unrelated party. Thus, acquisition of stock by gift, bequest, or nontaxable exchange (such as in a reorganization under I.R.C. section 368(a)(1)) was not a purchase. Exchanges of bonds, debentures, or other debts evidenced by securities for stock in internal restructuring normally qualified as a nontaxable recapitalization under old I.R.C. section 382(a) and were therefore not purchases within the meaning of the provision. Stock received in satisfaction of trade payables, however, was considered purchased stock.30

This difference in treatment (between debts evidenced by securities and other debts) gave rise to a number of cases construing the meaning of “security.” Courts generally limited the definition of securities to long-term obligations, excluding short-term notes. The line between “short-term” and “long-term” continues to be hazy, however. Some courts consider 5-year notes securities; others require maturities of at least 10 years.

The leading case in this area is a 1954 case in which the Tax Court addressed whether notes are securities for purposes of applying a 1939 code provision (old I.R.C. section 112(b)(5)) that was the predecessor of I.R.C. section 351. The court stated:

The test as to whether notes are securities is not a mechanical determination of the time period of the note. Though time is an important factor, the controlling consideration is an over-all evaluation of the nature of the debt, degree of participation and continuing interest in the business, the extent of proprietary interest compared with the similarity of the note to a cash payment, the purpose of the advances, etc. It is not necessary for the debt obligation to be the equivalent of stock since section 112(b)(6) specifically includes both “stock” and “securities.”31

Bonds payable from 3 to 10 years (averaging 6.2 years) have been classified as “securities” for recapitalization purposes by the IRS.32 Cases have defined the term “securities” to include bonds payable serially with a maximum maturity date of 7 years,33 6-year bonds,34 and 10-year promissory notes.35 A number of cases have held that debt obligations maturing in less than 5 years do not qualify as “securities.”36

Once it was determined that the restructuring involved a purchase of stock within the meaning of the statute, old I.R.C. section 382 would cause the NOL carryover to be lost unless the restructured corporation could demonstrate that it had avoided a prohibited ownership change or that it had not abandoned the loss corporation’s old trade or business. If there was a prohibited change in ownership and the trade or business test was not satisfied, then the NOL carryover was lost. A prohibited change in ownership was one in which the 10 largest shareholders of the loss corporation increased their ownership by 50 percent or more through stock purchases within the previous two taxable years. The total percent increase need not have occurred in a single transaction.

(c) Old I.R.C. Section 382(b)

As noted earlier in the chapter, I.R.C. section 381 permits a surviving corporation in certain tax-free reorganizations to inherit specified tax attributes (including NOL carryovers) of an acquired corporation. Old I.R.C. section 382(b) limited the ability of the surviving corporation to inherit NOL carryovers by reducing them if the stockholders of the loss corporation did not own at least 20 percent of the fair market value (FMV) of the outstanding stock of the reorganized corporation immediately after the reorganization.

The 20 percent ownership had to exist immediately after the reorganization and had to result from the ownership of stock in the loss corporation immediately before the reorganization. Thus, if a stockholder of the loss corporation also owned stock in the acquiring corporation prior to the acquisition, such stock was not considered owned by stockholders of the loss corporation in meeting the 20 percent requirement. Generally, a later sale of the stock did not affect the carryover, but a contractual agreement made prior to the reorganization to sell the stock acquired in the reorganization would have had a negative effect on the carryover.

The amount of reduction required by old I.R.C. section 382(b)(1) was determined by first calculating the percent of the FMV of the acquiring corporation’s outstanding stock owned by the loss corporation shareholders immediately after the reorganization. If the percent was greater than or equal to 20, no reduction was required. If the percentage was less than 20, the NOL was reduced by a percentage equal to five times the difference between the percent ownership and 20 percent. Thus, if the shareholders of a loss corporation received 12 percent of the stock of an acquiring corporation in a qualifying reorganization, 60 percent of the loss corporation’s loss survived.

§ 6.4 CURRENT I.R.C. SECTION 382

(a) Introduction

The Tax Reform Act of 1986 significantly altered I.R.C. section 382 and the manner in which companies can use NOLs. Where old I.R.C. section 382 limited the amount of the NOL that survived a change in ownership, new I.R.C. section 382 leaves the amount intact and limits instead the amount of income generated by the new entity against which the loss can be used.

(b) Overview

(i) Section 382 Limitation

The 1986 Act version of I.R.C. section 382 introduced an annual “section 382 limitation,” which is designed to minimize the effect of tax considerations on the acquisition of loss corporations. Other provisions of current I.R.C. section 382 are not necessarily consistent with the statute’s stated objectives of reducing the role of tax considerations in acquisitions and promoting certainty. For example, the rules reduce carryovers where one-third or more of the loss corporation’s assets are investment assets, and they completely eliminate carryovers where there is no continuity of business enterprise. The limitation permits loss carryovers to offset an amount of income equal to a hypothetical stream of income that would have been realized had the loss corporation sold its assets at FMV and reinvested the proceeds in high-grade tax-exempt securities. The law is considerably complicated by further conditions for loss survival, the coverage of built-in losses, special rules relating to ownership changes, and exceptions for bankrupt corporations.

The section 382 loss limitation provisions are relevant only in the event of a change in ownership of a loss corporation. Where old I.R.C. section 382 provided separate rules, depending on whether the ownership change resulted from a taxable purchase of stock or from a tax-free reorganization, new section 382 generally provides a single regime triggered by an “ownership change.” In general, an ownership change is a change of more than 50 percentage points in ownership of the value of stock of the loss corporation within a three-year period. A loss corporation is defined in I.R.C. section 382(k)(1) as a corporation entitled to use an NOL carryover, a current NOL, or a built-in loss.

The statute provides that a change in ownership can occur either as a result of an owner shift involving a 5 percent shareholder or an equity structure shift. Generally, owner shifts involve stock acquisitions and equity structure shifts involve statutory reorganizations. The two overlap, however, and, apart from effective dates, the distinction has little practical significance.

An NOL that arises before a change in ownership can be used in any period after the change, subject to the annual section 382 limitation. The ability of a loss corporation acquired by taxable purchase to preserve NOLs simply by continuing its historical business is eliminated. The myriad issues that arise in connection with determining whether a loss corporation has undergone an ownership change are discussed in § 6.4(d).

The section 382 limitation generally restricts the amount of income against which prechange NOLs can be applied in any postchange taxable year to the product of the FMV of the stock of the loss corporation37 immediately before the ownership change and the “long-term tax-exempt rate.” Any NOL limitation not used because of insufficient eligible taxable income in a given year is added to the section 382 limitation of a subsequent year.

(ii) Value of the Loss Corporation

The FMV of the loss corporation is thus one of the key factors in determining the use of NOLs. With respect to publicly traded companies, the price at which the stock is trading on an established exchange, or other applicable register, is generally presumed to be an accurate reflection of the FMV of a corporation’s stock. In support of this presumption, many cases hold that stock quotations are the best evidence of FMV.38 Nevertheless, as noted in Amerada Hess Corp. v. Commissioner,39 Moore-McCormack Lines, Inc. v. Commissioner,40 and Technical Advice Memorandum (T.A.M) 9332004,41 there are instances in which an exception to the general rule is appropriate in order to ascertain the true value of a corporation.42

In particular, as noted in Amerada, “[w]here the market exhibits such peculiarities as cast doubt upon the validity of that assumption, the market price must be either adjusted or discarded in favor of some other measuring device.”43

In support for valuing the corporation’s stock at an amount different from the stock trading price on the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE), the court said in Moore-McCormack:

While we are quick to recognize the persuasive importance of stock exchange prices in a stock valuation case, . . . nonetheless, we are convinced that we must carefully consider all of the evidence in the record which indicates the true fair market value for the 300,000 shares here involved. . . .

* * * *

Of paramount importance in our rejection of the mean stock market trading price as determinative of value here is the fact that [we are valuing] a lump, a block, an integrated package or bundle of rights representing ownership of 13 percent of a large and successful corporation. We must not think in terms of 300,000 individual shares of stock at so many dollars per share, but in terms of the overall dollar value of ownership of 13 percent of Moore-McCormack Lines, Inc., with the shares of stock meaningful not as something which can be converted to cash but merely as the formal evidence of ownership of the 13 percent.44

In this case, the court noted that it was not unreasonable under the circumstances that the per-share value resulting from the purchase price exceed the weighted average stock exchange price. Moreover, Congress recognized the fact that the price at which loss corporation stock changes hands in an arm’s-length transaction would be evidence of the value of the stock, although not necessarily conclusive evidence.45

In Technical Advice Memorandum (T.A.M.) 9332004, the IRS supported the taxpayer’s contention that the stock trading price was not representative of the value of the loss corporation. Consistent with comments contained in the legislative history to I.R.C. section 382, the IRS agreed that the ownership of the stock could, in certain circumstances, give rise to a control premium. The IRS concluded that the value of the loss corporation’s stock may be “determined using evidence and methods through which it is concluded that its value was different than the amount determined” by reference to NYSE trading price. The reference to the legislative history by the IRS can be reconciled with Treas. Reg. section 1.382-2(a)(3)(i) (which provides that for purposes of determining ownership percentage, each share of outstanding stock that has the same material terms is treated as having the same value) by recognizing that in T.A.M. 9332004, the IRS and the taxpayer were determining the total value of the loss corporation’s stock as opposed to an individual shareholder’s ownership percentage.

(A) Options

Another issue is whether options and similar interests should be included in determining stock value. I.R.C. section 382(k)(6)(B) gives the Secretary the power to “prescribe such regulations as may be necessary to treat warrants, options, contracts to acquire stock, convertible debt interests, and other similar interests as stock.” The legislative history to I.R.C. section 382 provides that such regulations may treat options and similar interests as stock for purposes of determining the value of the loss corporation.46 To date, such regulations under I.R.C. section 382(k)(6)(B) have not been released. Treas. Reg. section 1.382-2T(h)(4)(vii)(C) states, however, that whether an option was deemed exercised in determining whether an ownership change occurred47 shall have no impact on the determination of the value of the old loss corporation for the computation of the limitation.

In T.A.M. 9332004, the IRS noted that to the extent warrants for a loss corporation’s stock have value, such value derives from the potential they offer their holders to own the underlying stock. For purposes of determining the section 382 limitation, the IRS concluded that it is appropriate to take into account the actual value of warrants.

Based on the rationale of this ruling, it appears that the value of in-the-money options should be included in the value of the old loss corporation in computing the section 382 limitation. Although out-of-the-money options generally do not have a value equal to the underlying shares, they may nonetheless have a speculative or other value and presumably such value should be included in the annual limitation.

In addition, value may be controversial where changes in control are occasioned by reorganizations, particularly where the purchase price consists in whole or in part of stock of a nontraded corporation.

(iii) Long-Term Tax-Exempt Rate

The long-term tax-exempt rate is the highest of the federal long-term rates determined under I.R.C. section 1274(d), as adjusted to reflect differences between rates on long-term taxable and tax-exempt obligations in effect for the month in which the ownership change date occurs or the two prior months.48 The rates are published monthly in revenue rulings. The rate for ownership changes during January 2011 was 4.1 percent.49

The long-term tax-exempt rate is the yield on a diversified pool of prime, general obligation tax-exempt bonds with remaining periods to maturity of more than nine years. This rate has been subject to some criticism, because an investor would not assume the risks associated with a business venture merely to receive a long-term tax-exempt bond rate.

EXAMPLE 6.1

Assume that all of the stock of Target Corporation is acquired for $1 million on December 31, 2001, when the long-term tax-exempt rate is 10 percent. Target has 2002 taxable income, before NOL carryovers, of $60,000. The “section 382 limitation” for 2002 is $100,000 (10 percent of $1 million). The $40,000 of unused limitation in 2002 will increase the section 382 limitation for 2003 to $140,000. ![]()

(c) Allocation of Taxable Income for Midyear Ownership Changes

In general, when an ownership change occurs midyear, the loss corporation may use NOL carryovers to shelter taxable income allocable to the prechange period without limitation.50 Taxable income (loss) may be allocated to pre- and postchange periods on a daily pro rata basis. Alternatively, a loss corporation may elect to close the books on the ownership change date and allocate income (loss) between the pre- and postchange periods based on actual financial information.

For ownership changes occurring before June 22, 1994, a closing-of-the-books election required that the loss corporation obtain a private letter ruling from the IRS.51 On June 22, 1994, however, closing-of-the-books regulations were finalized and, as a result, the election can be made without the consent of the IRS.52 These regulations provide that loss corporations may allocate regular and/or AMT income (loss) between pre- and postchange periods based on either (1) closing the books or (2) daily pro rata allocation. The irrevocable closing-of-the-books election is made on the information statement required by Treas. Reg. section 1.382-11 for the change year.53

The regulations provide rules for allocating taxable income (loss) and net capital gain (loss) to pre- and postchange periods. The taxable income (loss) is determined without regard to capital gains or losses, the section 382 limitation, certain recognized built-in gains (losses), or “abusive gains.” The net capital gain (loss) is determined in a similar fashion. The net capital gain (excluding any I.R.C. section 1212 short-term capital losses) allocated to each period is offset by recognized built-in losses of a capital nature and capital loss carryovers subject to the section 382 limitation. Any taxable loss allocated to each period is then reduced by any capital gain allocable to the same period and then by any remaining capital gain from the other period.

The preambles to the proposed and final closing-of-the-books regulations provide that taxable income or loss allocated to either the prechange or the postchange period cannot exceed the total NOL or taxable income for the change year. For example, a corporation with prechange income of $2,000 and a postchange loss of $1,000 would allocate $1,000 of income to the prechange period and $0 to the postchange period if it makes a closing-of-the-books election. A few special points are noted next.

- Recognized built-in gains (losses). Certain recognized built-in gains (losses) (see infra § 6.4(h)) are allocated separately from operating income (loss).54 Thus, to the extent a loss corporation has a net unrealized built-in gain on the ownership change date, built-in gain recognized during the postchange portion of the year is allocated entirely to the postchange period, regardless of whether operating income (loss) is allocated based on daily proration or closing the books. To the extent a loss corporation has a net unrealized built-in loss on the ownership change date, built-in loss recognized during the postchange period is allocated entirely to the postchange period.

- Abusive gain. Income or gain recognized on the disposition of assets transferred to a loss corporation to ameliorate the annual limitation must be allocated entirely to the postchange period.55

- Extraordinary items. The regulations do not contain any special allocation provisions for extraordinary items. The preamble to the regulations, however, indicates that the IRS may give further consideration to the “desirability” of rules regarding the allocation of extraordinary items to pre- and postchange periods.

EXAMPLE 6.2 Daily Proration

Consider the following facts relating to Loss Corporation:

| FMV of all stock | $10,000,000 |

| NOL carryover (1/1/02) | 4,000,000 |

| Income for 2002 | 1,000,000 |

| Long-term tax-exempt rate | 6% |

All the stock of Loss Corporation is sold on October 1, 2002. The section 382 limitation is computed as follows:

- Value ($10,000,000) × long-term tax-exempt rate (6%) = $600,000 income per year that can absorb the NOL.

- No limitation applies to that portion of the year preceding (and including) the change date.56 Thus, 275/365 × $1,000,000 = $750,000 of income that can offset the loss.

- The portion of the taxable year remaining after the change date is subject to the section 382 limitation, which is also prorated. Thus, 90/365 × $600,000 (annual limitation) = $150,000 of postchange 2002 income can also absorb the NOL carryover. This analysis assumes that no closing-of-the-books election is made.

EXAMPLE 6.3 Closing-of-the-Books Method

A calendar-year loss corporation, XYZ, with NOL carryovers of $25 million and a value of $60 million has an ownership change on March 31, 2005. Income from the first quarter is $15 million, while income for the remainder of the year is $1 million. The resulting applicable limitation for 2005 would be approximately $3.074 million [$60 million × 6.83% AFR (hypothetical applicable long-term tax-exempt rate) × 3/4 postchange period]. Based on a daily proration, total income of $16 million would be allocated proportionately throughout the year. Thus, XYZ may fully shelter the $4 million of income, which is allocated to the prechange period, with its prechange NOL carryovers. XYZ may, however, shelter only $3,074,000 of the $12 million of income allocated to the postchange period. If instead, XYZ elected to use the closing-of-the-books method, XYZ could fully shelter pre- and postchange income, because the $1 million of income allocated to the postchange period is less than both the limitation for 2005 and the available NOL carryovers.

See § 6.4(h)(iii) for an analysis of the treatment of items that occur on a change date. ![]()

(d) Ownership Change

Recall that the section 382 loss limitation rules do not come into play unless there has been an ownership change. Until an ownership change takes place, a loss corporation can use all of its losses without a “section 382 limitation,” and none of the numerous restrictions and limitations of I.R.C. section 382 applies. An ownership change occurs if, on a testing date, the percentage of stock of a loss corporation owned by one or more 5 percent shareholders has increased by more than 50 percentage points relative to the lowest percentage of stock of the old loss corporation owned by those 5 percent shareholders at any time during the testing period (generally, three years).57

The determination of whether an ownership change has occurred on a date on which there has been an owner shift (a “testing date”) is made by comparing the increase in value in percentage stock ownership (if any) for each 5 percent shareholder as of the close of the testing date, with the lowest percentage of stock owned by each such 5 percent shareholder during the three-year testing period. The three-year period generally does not begin before the first day of the first tax year from which there is a loss or credit carryover to the first postchange year.58 Stock owned by persons who own less than 5 percent of a loss corporation is generally treated as stock owned by one or more 5 percent shareholder(s).59

The ownership change test bears a distinct similarity to old I.R.C. section 382(a) and the definition of “purchase.” Under the prior law, a determination was made as to whether the 10 largest shareholders of the loss corporation increased their ownership interest of the loss corporation by 50 percentage points or more over the previous two taxable years. Prior law, however, had two completely different tests, depending on whether there was a taxable purchase (10 largest shareholders and 50 percent change of ownership) or a tax-free reorganization (20 percent continuity of shareholder interest). Current I.R.C. section 382(g) has one test: an ownership change by 5 percent shareholders totaling more than 50 percentage points. Although the statutory framework categorizes an ownership change as either (1) an owner shift involving 5 percent shareholders or (2) an equity structure shift (i.e., a reorganization), there is usually no distinction between the two; they are really the same test.

In certain situations, attribution rules apply for I.R.C. section 382 purposes. The aggregation of shares could allow actual shifts in ownership among family members to occur without affecting the corporation’s cumulative section 382 owner shift percentage.60

In determining whether an ownership change has occurred, the general rule is that changes in the holding of all “stock” are taken into account, except that preferred stock described in I.R.C. section 1504(a)(4) is generally disregarded.61 I.R.C. section 1504(a)(4) stock is preferred stock that is nonvoting and nonconvertible, and that does not participate in corporate growth and has a reasonable redemption or liquidation premium. Although such preferred stock is not counted as stock for purposes of determining whether there is an ownership change, it is generally included as stock for purposes of determining the value of the loss corporation.62 There are several additional exceptions to the definition of stock, each of which functions as an anti-abuse rule. More specifically, if certain conditions are met, one exception provides that an ownership interest that is otherwise treated as stock may not be treated as stock for purposes of determining whether an ownership change has occurred. Another exception provides that an ownership interest that otherwise would not be treated as stock and is not an option may be treated as stock in determining whether an ownership change has occurred and in determining the value of a loss corporation to compute the section 382 limitation.63

(i) Examples of Ownership Changes Involving Sales among Shareholders

The determination of whether an ownership change has occurred is demonstrated in Examples 6.4 through 6.7.

EXAMPLE 6.4

Drew Corporation Shareholders

In this simplified situation, where all ownership changes took place on one day (December 31, 2003), there was no statutory ownership change of the loss corporation. Shareholders B, C, F, and G increased their stock ownership by a total of 47 percentage points, but there was no change in stock ownership aggregating more than 50 percentage points. If on December 31, 2003, however, shareholder A also purchased all of D’s stock interest, there would be an ownership change for Drew Corporation. A would own 20 percent of Drew Corporation and would have increased his interest from the lowest point in the three-year period by 10 percentage points. This, coupled with the other shareholders’ 47-point increase, would result in an increase of more than 50 percentage points. ![]()

EXAMPLE 6.5

Bryce Corporation Shareholders

In 2000, Bryce was a public company. No shareholder owned 5 percent of the stock. At the end of 2003, four individuals purchased all the stock of Bryce. There was a 100 percentage point change and thus an ownership change on December 31, 2003. (A public-to-private or leveraged buyout of a public company will be an ownership change; a private company that goes public will also undergo an ownership change.) If, pursuant to a public offering of stock on January 1, 2004, individuals A, B, C, and D each decrease their holdings from 25 percent to 4 percent, there will be an 84 percentage point change. On January 1, 2004, the public is treated as one 5 percent shareholder that owns 84 percent (all less-than-5-percent shareholders are grouped together, but A, B, C, and D are treated separately because they were previously 5 percent shareholders). Because the public owned no stock as of December 31, 2003, there was an 84 percentage point increase by the public. The facts of this example would not qualify for either the cash issuance or the small issuance exceptions described in § 6.4(e)(iii). ![]()

An existing public company whose stock is widely traded and whose shareholders completely change during a three-year period does not experience an ownership change. This is because all less-than-5-percent shareholders are treated as one or more 5 percent shareholders, such that a complete change in small public shareholders will, under the statute, represent a zero percentage point change during the three-year period.

Note, however, that a group of shareholders acting pursuant to a plan may be treated as a separate entity, even though none of the shareholders individually acquires 5 percent of the loss corporation’s stock.64 For example, assume Public owns 100 percent of Loss. If Q buys newly issued stock constituting 46 percent of the outstanding stock of Loss Corporation from Loss, and five friends acting in concert each buy 1 percent of the Loss stock from Public, an ownership change will take place. (The new stock in this transaction would not qualify for either the cash issuance or the small issuance exceptions described in § 6.4(e)(iii)). This rule applies for testing dates after November 19, 1990. Because Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) regulations require disclosure of owners acting in concert, taxpayers may generally rely on the absence of such disclosures to conclude that no such separate entity exists.65

Once a shareholder is a 5 percent shareholder at any time within the testing period, he or she is a separate shareholder even though the interest held may be less than 5 percent at other relevant times within the testing period.66 Assume a loss corporation (L) has 25 separate 4 percent shareholders. Five of those shareholders sell 1 percent each of their stock to the remaining 20 shareholders (each of whom ends up owning 5 percent of L). There is a presumption that each of the 20 shareholders (who own 5 percent of L) owned no stock in L beforehand, causing a 100 percentage point shift in the ownership of L and an ownership change.67 This presumption is overcome by actual knowledge that the 20 shareholders actually owned 4 percent each in L beforehand, resulting in only a 20 percentage point owner shift.68

EXAMPLE 6.6

MVL Corporation Shareholders

At the end of 2000, there is only a 40 percentage point increase (A = 5, B = 10, and D = 25). At the end of 2001, there is a 65 percentage point increase compared to the lowest point in the period (A = 10, B = 50, D = 5) and, thus, an ownership change. At the end of 2002, it would be improper to conclude that there was another ownership change. Although there is a 55 percentage point increase in A, B, and D’s interest between January 1, 2000, and December 31, 2002 (a three-year period), I.R.C. section 382(i)(2) provides that once there is an ownership change (on December 31, 2001), the testing period for determining whether a second ownership change has occurred “shall not begin before the first day following the change date for such earlier ownership change,” which, in this example, is January 1, 2002. Thus, from January 1, 2002, to December 31, 2002, there is only a 40 percentage point change (A = 10, D = 10, E = 20). ![]()

Because an increase in stock ownership is measured by reference to the lowest percentage of stock owned by a 5 percent shareholder at any time during the testing period, if a 5 percent shareholder disposes of loss corporation stock and subsequently reacquires all or a portion of such stock during the testing period, the increase resulting from the subsequent acquisition is taken into account in determining whether an ownership change has occurred (even if the percentage ownership between the first and last day of the testing period is the same or has decreased).

EXAMPLE 6.7

On June 1, 2002, M sold 35 percent of Booth Corporation stock to N and on August 1, 2002, M purchased O’s 20 percent stock interest.

An ownership change takes place on August 1, 2002. Even though M’s interest has decreased from 40 percent to 25 percent on the testing date (August 1, 2002), M’s interest is 20 percentage points greater than its lowest percentage of stock owned during the three-year testing period. This, coupled with N’s increase of 35 percentage points during the three-year period, results in a 55 percentage point increase and an ownership change.

This is the rule even though there would be no ownership change if the two sales were reversed in time. Thus, if M purchased O’s 20 percent interest on June 1, 2002, and M sold 35 percent to N on August 1, 2002, there would be no ownership change. On the testing date (August 1, 2002), M has not increased his interest in T Corporation from any point within the three-year period. M’s increase of 20 percentage points from February 1, 2001, to June 1, 2002, is immaterial to the August 1, 2002, testing date. Therefore, only N’s increase of 35 percentage points occurred on the August 1, 2002, testing date.

Even if M first sold a 35 percent stock interest to N and then purchased 20 percent from O (as in the original facts), there would still not be an ownership change if the sale and purchase took place on the same day.69 ![]()

One I.R.C. section 382 issue that has lurked in the shadows for many years is now receiving significant attention. This issue is how to deal with fluctuations in the relative value of different classes of stock when computing an ownership change. This phenomenon of an ownership change resulting from fluctuations in value may be illustrated as follows:

Assume that a corporation, on formation, issues 100 shares of common stock to individual A at a price of $10 per share (for a total of $1000) and 5 shares of voting preferred stock to individual B at $20 per share (for a total of $100).

One year later A sells 10 shares of common stock to individual C for $5 when the price of the common stock has declined from $20 per share to 50 cents per share. This sale results in a testing date. Individual B continues to own the preferred stock, and such stock retains its value of $20 per share. If fluctuations in value are not removed from the computation of percentage increase in interest by the shareholders, the corporation will have an ownership change, even though only 10 percent of the common stock is transferred and the voting preferred stock continues to be held by the same shareholder. This is because B’s interest has increased from a low of approximately 9 percent of the value of the corporation at the beginning of the testing period (on formation the voting preferred was worth $100 of a total $1100 of equity value) to approximately 67 percent of the equity value of the corporation on the testing date (preferred stock is now worth $100 of a total of $150 of total equity).

The IRS provided guidance regarding this issue in Notice 2010-50.70 The notice provides two basic methodologies for addressing fluctuations in value. The first is the full value methodology. The notice describes this approach including this illustrative example:

Under a Full Value Methodology, the determination of the percentage of stock owned by any person is made on the basis of the relative fair market value of the stock owned by such person to the total fair market value of the outstanding stock of the corporation. Thus, changes in percentage ownership as a result of fluctuations in value are taken into account if a testing date occurs, regardless of whether a particular shareholder actively participates or is otherwise party to the transaction that causes the testing date to occur; essentially, all shares are “marked to market” on each testing date.

Example: Upon formation, corporation X issues $20 of convertible preferred stock to A and issues two shares of common stock to B for $80, such that A and B own 20 percent and 80 percent, respectively, of X. The fortunes of X deteriorate, and, two years later, when the common stock has a value of $2.50 per share and the preferred stock has a value of $20, B sells one share of common stock to C. At the time of B’s sale to C, X is a loss corporation. On that testing date, A will be treated as increasing its proportionate interest from 20 percent to 80 percent ($20/$25) under the Full Value Methodology as a result of the upward fluctuation in value of the preferred stock relative to the common stock.

The second methodology is the hold constant principle (HCP). The notice describes the HCP including this illustrative example:

Broadly stated, under the Hold Constant Principle, the value of a share, relative to the value of all other stock of the corporation, is established on the date that share is acquired by a particular shareholder. On subsequent testing dates, the percentage interest represented by that share (the “tested share”) is then determined by factoring out fluctuations in the relative values of the loss corporation’s share classes that have occurred since the acquisition date of the tested share. Thus, as applied, the HCP is individualized for each acquisition of stock by each shareholder. Moreover, the ownership interest represented by a tested share is adjusted for the dilutive effects of subsequent issuances and the accretive effects of subsequent redemptions following the tested share’s acquisition date.

Example: Upon formation, corporation X issues $20 of convertible preferred stock to A and issues two shares of common stock to B for $80, such that A and B own 20 percent and 80 percent respectively, of X. The fortunes of X deteriorate, and, two years later, when the common stock has a value of $2.50 per share and the preferred stock has a value of $20, B sells one share of common stock to C. At the time of B’s sale to C, X is a loss corporation. On that testing date, although A actually owns 80% of the value of X, A will be treated as owning 20% of the value of X for purposes of § 382 (g), under the Hold Constant Principle.

The notice further provides that there are alternative methodologies for implementing the HCP. One approach—HCP1—recalculates the HCP percentage represented by a tested share to factor out changes in its relative value since the share’s acquisition date.71 Generally, this is accomplished by calculating the percentage interest represented by a tested share on a testing date, beginning with the value of the tested share on the testing date, and then making adjustments based on the changes in relative value of the tested share to the value of all the stock of the loss corporation that have occurred since the tested share’s acquisition date. Another approach (HCP2) for implementing the HCP tracks the percentage interest represented by a tested share from the date of acquisition forward, adjusting for subsequent dispositions and for the subsequent issuance or redemption of other stock. Under this approach, the increase in percentage ownership represented by the acquisition of a tested share during the testing period is established on the date the tested share is acquired. This increase is reduced (but not below zero) for subsequent dispositions of shares by the owner. The notice provides that taxpayers may use any methodology that is a reasonable application of either a full value methodology or the HCP in determining when an ownership change has occurred. The IRS has issued private rulings in this area (many before the issuance of Notice 2010-50), most of which to date appear to have used an HCP1 approach.72

The notice requires that a taxpayer generally must employ a single methodology consistently to all testing dates in a “consistency period.” With respect to a particular testing date (the “current testing date”), the consistency period includes all prior testing dates, beginning with the latest of (1) the first date on which the taxpayer had more than one class of stock; (2) the first day following an ownership change; or (3) the date six years before the current testing date. The notice also addresses other issues that arise due to the fluctuation in value issue.

(ii) Other Transactions Giving Rise to Ownership Changes

Transactions other than sales among shareholders can also result in ownership changes. These include redemptions (including I.R.C. section 303 redemptions to pay death taxes), public offerings, split-offs, I.R.C. section 351 incorporations, recapitalizations, reorganizations, and stock becoming worthless. This is a significant broadening of the transactions covered, compared with the prior-law definition of a “purchase.” Only changes in stock ownership resulting from gift, death, divorce, or separation,73 pro rata dividends and pro rata spin-offs, by the very nature of the distribution, do not result in an ownership change.

It may be possible to structure the stock of an entity to prevent an ownership change from occurring. For example, the IRS has ruled that if a company’s stock certificates are labeled with a legend restricting the transfer of the certificate if such transfer would cause an ownership change, such an arrangement is sufficient to preclude an ownership change. The mechanics of the restriction would prohibit any transfer with the potential to cause an ownership change, including a return of the shares represented by the certificates to non-5-percent shareholders, a return of the purchase price to the purported acquirer, and a return of all vestiges of ownership (e.g., dividends) to the selling shareholder.74

(iii) Examples of Ownership Changes Resulting from Other Transactions

EXAMPLE 6.8

Public Offering Missy Corporation Shareholders

On June 15, 2000, A sells 300 shares to B. There is no ownership change, because B’s interest has increased by only 30 percentage points. On June 15, 2001, C, D, and E each buy 100 newly issued Missy shares from Missy. The latter issuance of shares, coupled with the prior sale, still yields only a 47 percentage point increase in stock ownership. When A has 200 shares redeemed on December 15, 2001, there is a 55 percentage point increase and an ownership change. The issuance would not qualify for either the cash issuance or the small issuance exceptions described in § 6.4(e)(iii). ![]()

EXAMPLE 6.9 Split-Off

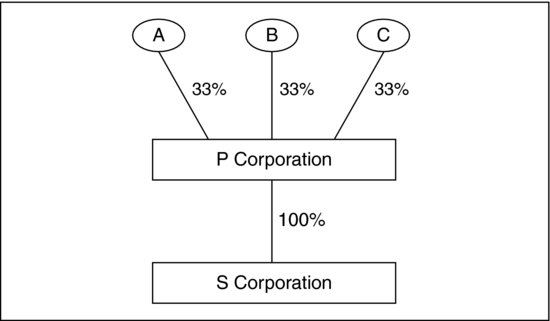

A pro rata dividend or spin-off of loss corporation S to individuals A, B, and C results in a zero percentage point change. (See Exhibit 6.1.) A, B, and C own one-third of S both before and after the transaction. If loss corporation S is distributed to C in complete redemption (under I.R.C. section 302(b)(3)) of C’s interest in P, or if P splits off S to C under I.R.C. section 355 in complete surrender of C’s interest in P, there is an increase of 67 percentage points and an ownership change. C’s interest increased from a 33 percent indirect interest in S to a 100 percent direct interest in S. If, in the same redemption or split-off above, P is the loss corporation, there is no ownership change. Both A and B would have increased their interest in P from 33 percent to 50 percent for only a combined 34 percentage point interest. ![]()

Exhibit 6.1 Corporate Spin-Off Resulting in Zero Percentage Point Change

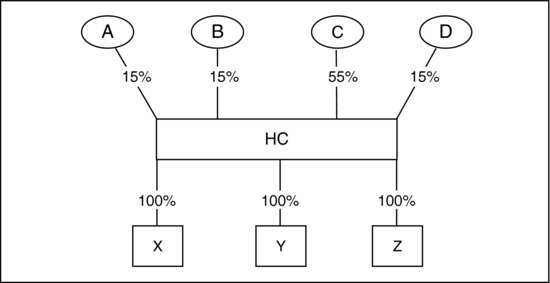

EXAMPLE 6.10 I.R.C. Section 351 Transfer

Even the mere formation of a holding company can be an ownership change.

Assume individual A owns 100 percent of the stock of X Corporation, individual B owns 100 percent of the stock of Y Corporation, and individual C owns 100 percent of the stock of Z Corporation. All corporations have NOL carryovers. A, B, and C each transfer 100 percent of the stock of their respective corporations to a new holding company (HC), and investor D transfers cash to the HC. After the transaction, the corporate structure is as shown in Exhibit 6.2.

With respect to both X and Y, there has been an ownership change. C and D own 55 percent and 15 percent, respectively, of corporations X and Y after the creation of the holding company. The introduction of new 5 percent shareholders creates an 85 percentage point increase in the shares of X and Y. There is no ownership change, however, as to Z Corporation, because A, B, and D each own 15 percent afterward (zero beforehand) for a total increase of 45 percentage points. ![]()

EXAMPLE 6.11 Recapitalization

Nonvoting, nonconvertible, nonparticipating, preferred stock with a reasonable redemption and liquidation premium is disregarded as stock in determining whether there has been a more than 50 percentage point increase.75 Thus, a stock-for-stock as well as a debt-for-stock recapitalization can result in an ownership change.

Assume Loss Corporation is owned by individual A (75 percent) and individual B (25 percent). If A exchanges his common stock for an issuance of nonvoting preferred stock (under I.R.C. section 1504(a)(4)), B will be deemed to own all of Loss Corporation after the recapitalization. A’s preferred stock interest is disregarded. Similarly, if C, D, and E (creditors of Loss Corporation) surrender their claims for more than 50 percent of Loss Corporation stock, there will be an ownership change. ![]()

Exhibit 6.2 Corporate Structure after Transfer to a Holding Company

EXAMPLE 6.12 Worthlessness

Under prior law, if stock held by a taxpayer became worthless during the tax year, a loss deduction was allowed. Even if a worthless stock deduction had been claimed by a parent corporation with respect to stock of a nonconsolidated subsidiary, the NOL carryovers of the subsidiary survived and could be used to offset future income of the subsidiary.76

Current I.R.C. section 382(g)(4)(D) provides that a more-than-50-percent shareholder who treats stock as having become worthless is treated as a new shareholder on the first day of the succeeding taxable year. Thus, an ownership change results and the NOL carryovers are subject to the section 382 limitation.77 ![]()

(iv) Equity Structure Shift

An equity structure shift is a reorganization other than a mere change in form (F reorganization) or a divisive reorganization (generally, a spin-off under I.R.C. section 355).78 An equity structure shift that results in an increase of more than 50 percentage points in the stock ownership of a loss corporation is an ownership change.79 The identity of the loss corporation as the transferor or acquiring corporation is irrelevant. Thus, if X Corporation (a loss corporation) merges into Y Corporation (also a loss corporation) in exchange for 60 percent of the stock of Y, there is an equity structure shift. Because the preexisting shareholders of Y own only 40 percent of Y after the merger, there is no ownership change for X, but there is an ownership change for Y. The result would be the same if Y merged into X and the Y shareholders received 40 percent of X. As previously discussed, only changes by shareholders owning 5 percent or more are counted. Although the less-than-5-percent shareholders are aggregated and treated as one shareholder, the less-than-5-percent shareholders of the transferor and acquiring corporation are segregated and treated as separate 5 percent shareholders. For this reason, the relative FMVs of the transferor and acquiring corporation may determine whether an equity structure shift is an ownership change and to which corporation (i.e., the acquiring corporation or the target corporation assuming both the acquiring and target corporations are loss corporations).80

(v) Purchases and Reorganizations Combined

A purchase and an equity structure shift can be combined within the testing period to cause an ownership change.

EXAMPLE 6.13

Loss Corporation (L) has been owned by individual B for 10 years. Individual C purchased 20 percent of L from B on August 1, 2000. On February 1 5, 2002, L merged into P Corporation and in the merger the L shareholders received 55 percent of P.

The equity structure shift on February 15, 2002, caused an ownership change. Even though the “former” shareholders of L (as of February 15, 2002) maintained a 55 percent interest in P, B did not retain more than 50 percent of P. C is not considered a former shareholder of L, because C acquired her interest within the three-year testing period. After the merger, the composition of the P shareholders is:

| Shareholder | Percentage in P |

| B | 44% |

| C | 11 |

| Historical P shareholders | 45 |

| 100% |

Because C, along with the historical P shareholders, will own more than 50 percentage points (56) following the merger, there is an ownership change with respect to L.

The result would not be different if the merger had preceded the purchase (i.e., if the merger took place on August 1, 2000, and C’s purchase occurred on February 15, 2002). The August 1, 2000, equity structure shift (merger) would not have resulted in an ownership change, because the historical P shareholders would only own 45 percent of P, the surviving corporation. C’s purchase of 11 percent of P from B would be an ownership change, however, because, within the testing period, the historical P shareholders (45 percent) and B (20 percent) increased their percentage interest in L’s losses by more than 50 percentage points. ![]()

(vi) Undoing a Section 382 Ownership Change

The IRS ruled that when a bankruptcy court treated a purchase of stock void ab initio, the purchaser would not be treated as having acquired ownership of the stock for purposes of section 382, as long as the court’s order remained in effect and was not set aside by a higher court. It is interesting to note that the court had ordered the purchaser of the stock to sell it, with the proceeds payable to the purchaser up to its net costs and the remainder, if any, payable to a section 501(c)(3) charity.81

(vii) Bailout-Related Section 382 Relief82

(A) Introduction

The IRS issued a series of notices in the I.R.C. section 382 area in late 2008 and early 2009 to address the economic and financial crisis. Discussing the notices (as well as related legislative developments) chronologically allows the reader to track the evolution of this guidance in the context of its historical background. Most of the bailout-related I.R.C. section 382 guidance is related to determining if and when a testing date would occur after a government purchase of stock in a loss corporation. These stock purchases provided necessary capital and in essence bailed out certain troubled corporations. If there is no testing date, then there can be no I.R.C. section 382 ownership change. If there is no I.R.C. section 382 ownership change, I.R.C. section 382 will not limit the utilization of prechange losses. The IRS also issued two other I.R.C. section 382 notices in this time frame. One notice addressed the treatment for losses on loans or bad debts to banks (also described together with its statutory repeal below), and the other addressed the treatment of capital contributions and is discussed in more detail in that portion of this chapter.

The underlying idea behind most of the bailout-related notices discussed below (with the exception of Notice 2008-83) appears to be that the U.S. government, which became a shareholder in certain loss corporations, would not engage in NOL trafficking, the practice I.R.C. section 382 is designed to prevent. Thus, during uncertain economic times, Treasury clarified I.R.C. section 382 for situations when the U.S. government or one of its agencies becomes a shareholder in a loss corporation.

The notices rely either explicitly or implicitly on authority provided to Treasury by I.R.C. section 382(m) to generally prescribe regulations to carry out the purposes of I.R.C. section 382. In addition, the notices related to the Emergency Economic Stabilization Act of 2008 (the Emergency Act), described below, rely on the authority granted to Treasury by section 101(c)(5) of the Emergency Act to issue regulations and other guidance as may be necessary or appropriate to carry out the purposes of Emergency Act.

(B) Notice 2008-76: Fannie Mae/Freddie Mac

At first, Treasury addressed a very small subset of loss corporations. Notice 2008-76, issued September 7, 2008, addressed certain acquisitions by the U.S. government pursuant to the Housing and Economic Recovery Act of 2008 (the Housing Act). The Housing Act allowed the U.S. government to invest in the Federal National Mortgage Association (Fannie Mae), the Federal Home Loan Mortgage Corporation (Freddie Mac), and the Federal Home Loan Bank system.

The notice announced that the IRS and Treasury would issue regulations to address how I.R.C. section 382 would apply to Housing Act acquisitions. The regulations would preclude any date on or after the date on which the United States (or any agency or instrumentality thereof) acquires either stock83 or an option to acquire stock in the loss corporation from being an I.R.C. section 382 “testing date.” The wording of the notice indicates that after the government’s buy-ins, there would be no I.R.C. section 382 testing dates (even after the government is no longer a shareholder in these loss corporations) unless and until there is further guidance.

The regulations would generally apply on or after September 7, 2008. Notice 2008-76 is sometimes referred to as the Fannie Mae/Freddie Mac Notice.

(C) Notice 2008-84: More-than-50-Percent Interest

The U.S. government did not stop its bailout assistance with the Housing Act. It next moved on to investing in other loss corporations, furthering the need for more I.R.C. section 382 guidance.

Notice 2008-84, issued September 26, 2008, addressed certain acquisitions by the U.S. government that were not covered by Notice 2008-76. These acquisitions resulted in the government becoming a direct or indirect owner of a more-than-50-percent interest in a loss corporation.84 The notice announced that Treasury and the IRS would issue regulations defining the term “testing date” to exclude any date as of the close of which the United States directly or indirectly owns a more-than-50-percent interest in the loss corporation, notwithstanding any other provision of the I.R.C. or the regulations. Thus, the loss corporation would only have to start tracking its I.R.C. section 382 position on any date as of the close of which the United States does not directly or indirectly own a more-than-50-percent interest in the loss corporation. The regulations would generally apply for any tax year ending on or after September 26, 2008.

(D) Notice 2008-83: Banks

This next notice created significant controversy and was eventually legislatively overturned, generally prospectively.

(1) The Notice

Notice 2008-83, issued October 1, 2008, provided guidance to banks on the treatment of losses on loans or bad debts. Unlike the first two notices, this guidance applied with or without government involvement triggering an ownership change.

As background, in addition to limiting NOLs, I.R.C. section 382 can limit certain deductions that were “built in” at the time of the ownership change. Generally, if a corporation is in a net unrealized built-in loss position at the time of the change (i.e., the FMV of its assets is less than the tax basis with certain other adjustments), then such losses/deductions, when recognized within a certain time frame, could also be subject to the I.R.C. section 382 limitation.85

The notice stated that for purposes of I.R.C. section 382(h), any deduction properly allowed after an ownership change to a bank with respect to losses on loans or bad debts (including any deduction for a reasonable addition to a reserve for bad debts) would not be treated as a built-in loss or deduction that is attributable to periods before the change date. Thus, although the banks would still need to include such losses into the net unrealized built-in loss calculations, the losses triggered after an ownership change would not constitute recognized built-in losses (and thus would not be subjected to an I.R.C. section 382 limitation). The notice applied to corporations that were banks (as defined in I.R.C. section 581) both immediately before and after the ownership change date. The banks were allowed to rely on the treatment set forth in the notice “unless and until there is additional guidance” (i.e., the notice appeared to apply both prospectively and retrospectively).

The notice drew the ire of Congress. Senator Chuck Grassley, ranking minority member of the Senate Finance Committee, requested an investigation into the issuance of the notice.86

(2) Repeal of Notice 2008-83

The ARRA repealed Notice 2008-83, generally prospectively, reasoning that Treasury was not authorized under section 382(m) to provide exemptions or special rules that are restricted to particular industries or classes of taxpayer. However, the ARRA left Notice 2008-83 in effect for any ownership change occurring on or before January 16, 2009. In addition, the notice is in effect for changes occurring after January 16, 2009, if such changes are (1) pursuant to a written binding contract entered into on or before January 16, 2009, or (2) pursuant to a written agreement entered into on or before that date and the agreement was described on or before that date in a public announcement or in a filing with the SEC required by reason of the ownership change.

(E) Notice 2008-100: Capital Purchase Program

The next step the U.S. government took in addressing the financial crisis was the Emergency Economic Stabilization Act of 2008 (the Emergency Act). Notice 2008-100, issued October 15, 2008, discussed how I.R.C. section 382 would apply to loss corporations whose instruments were acquired by Treasury under the Emergency Act’s Capital Purchase Program (CPP). The CPP authorized Treasury to acquire preferred stock and warrants from qualifying financial institutions.

Notice 2008-100 was later amplified and superseded by Notice 2009-14, which was in turn amplified and superseded by Notice 2009-38. Further, Notice 2009-38 was amplified and superseded by Notice 2010-2. Notice 2010-2 is discussed in detail below. Accordingly, we will not discuss Notice 2008-100, Notice 2009-14, or Notice 2009-38 in detail.

(F) Notice 2009-14: Capital Purchase Program and Troubled Asset Relief Program

Notice 2009-14, issued January 30, 2009, announced that Treasury and the IRS would issue regulations implementing certain rules described in the notice. Notice 2009-14 covers five programs established under the Emergency Act (compared to Notice 2008-100, which covered only the CPP in general):

1. Capital Purchase Program for publicly traded issuers (Public CPP)

2. Capital Purchase Program for private issuers (Private CPP)

3. Capital Purchase Program for S corporations (S Corp CPP)

4. Targeted Investment Program (TARP TIP)

5. Automotive Industry Financing Program (TARP Auto)

Notice 2009-14 amplified and superseded Notice 2008-100 in addressing issues raised by the U.S. government’s investment pursuant to the Emergency Act. However, as noted, Notice 2009-14 was itself amplified and superseded by Notice 2009-38, which in turn was amplified and superseded by Notice 2010-2.

(G) Notice 2009-38: Treasury Acquisitions under Emergency Act Programs

Following the issuance of Notice 2009-14, Treasury added several other programs pursuant to its authority under the Emergency Act. This, plus the need for additional guidance on existing Emergency Act programs, apparently led Treasury to issue another I.R.C. section 382 notice. Notice 2009-38, issued April 13, 2009, provides additional guidance regarding the application of I.R.C. section 382 to corporations whose instruments are acquired by Treasury pursuant to the Emergency Act.

Notice 2009-38 expands the number of programs covered by Notice 2009-14 from five to eight. The three added programs are:

1. Asset Guarantee Program

2. Systemically Significant Failing Institutions Program

3. Capital Assistance Program for publicly traded issuers (TARP CAP)

Notice 2009-38 was amplified and superseded by Notice 2010-2.

(H) Notice 2010-2: Treasury Acquisitions and Dispositions under Emergency Act Programs

Notice 2010-2, released December 16, 2009, amplified and superseded Notice 2009-38. The primary goal of issuing one more notice appears to be to address the treatment of the disposition of shares held by Treasury via a public offering. Otherwise, most of the rules originally outlined in Notice 2009-38 stayed the same.