Chapter 1

The Need for Change in the Practice of Public Health

Learning Objectives

- Explain the primary mission of public health

- Define health

- Define primary prevention

- Describe population health

- Discuss the history of public health and its impact on current public health services

- Identify the characteristics of quality in the field of public health

Mission and Services of Public Health

Public health organizations, particularly government agencies, are pulled in many directions, and have had difficulty in both addressing the multiple determinants of health and providing population-centered services to improve community health outcomes. Determinants of health are the factors in the personal, social, economic, and environmental areas of life that affect the health status of individuals and populations.

The challenges facing modern-day societies require interventions and services that move beyond the traditional local public health offerings of personal health care, communicable disease control, and enforcement of environmental health laws. Public health organizations are now expected to understand and address the many factors affecting health produced by the environment, social relationships, communities, and institutions—while in the process forming multiple partnerships to improve health around the globe.

Mission of Public Health

The definition of mission of public health has undergone transformation over time. The earliest mission of public health involved the control of communicable diseases, such as cholera, smallpox, tuberculosis, and yellow fever, that inevitably led to epidemics. The most recent definition originated from the Institute of Medicine (IOM) in 2002 and is much broader. The IOM declared that the new mission of public health encompasses the organized efforts of society toward assuring conditions in which people can be healthy. Society has a dual interest in reducing communities' exposure to risk factors known to negatively affect health and in promoting healthy conditions that create and sustain health in the social and environmental spheres of everyday life.

Society's interest stems from the concept of health as a primary public good that promotes the many goals of a society, including the ability of humans to work, to enter into social relationships, and to participate in a political process. As a result of this broad interest, public health practitioners are expected to focus primarily on the health of community populations as opposed to expending their resources on the treatment of individuals for health problems that are usually addressed by physicians or hospitals providing medical services.

Population-Centered Health Services

A public health organization is expected to provide primary prevention services to a population. Primary prevention approaches to improving the health status of populations seek to inhibit the occurrence of disease and injuries by reducing exposure to risk factors that cause health problems. In other words, public health services intended to fulfill the mission of public health address the fundamental causes of disease and help foster or sustain conditions that contribute to health, with the goal of preventing undesirable health outcomes (Public Health Leadership Society, 2002). Public health's role also extends to health promotion and helping people gain control of their life and the determinants of health, creating healthier community populations.

What is a population-centered service? To answer this question, we must define the terms population and health. A population is a group of people with shared characteristics, such as location, race, ethnicity, occupation, or age. Community is a word that is often used interchangeably with the term population. Students in a school system, migrant and seasonal farmworkers, employees of the automobile industry, and county residents and visitors are all examples of populations or communities on which public health organizations may choose to focus and in which they might plan services designed to improve overall health outcomes, such as by reducing obesity or cancer rates.

A population-centered service organization seeks to improve health across multiple individuals over a period of time. Healthy People 2010 and 2020 are national initiatives to promote health and prevent disease by setting and monitoring national health objectives (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 1999a, 2009d). Proponents of these initiatives work collaboratively with partners to realize the goal of healthy people in healthy communities, a population-centered approach to improving the nation's health. Two examples of the proposed population-centered goals for Healthy People 2020 are increasing the quality and years of healthy life for individuals of all ages and eliminating health disparities among segments of the population that experience poorer health due to gender, race, ethnicity, education, income, disabilities, geographic location, or sexual orientation—the social determinants of health (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [HHS], 2011). Population-centered health services designed to increase rates of physical activity across communities are examples of public health interventions that incorporate evidence, are population-centered, and promote health. The application of evidence-based practices increases the likelihood of achieving improved community health outcomes. Evidence-based public health practice is the use of the best available scientific evidence to make informed decisions about public health services (Brownson, Fielding, and Maylahn, 2009).

Defining and Modeling Health

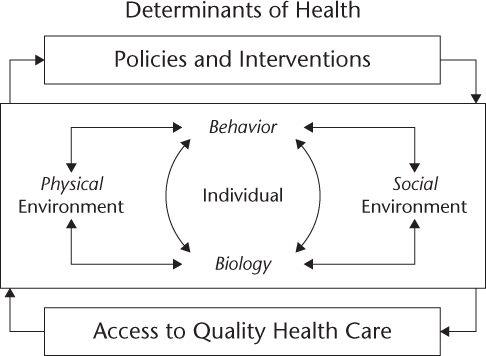

A current and popular definition of health was first presented by the World Health Organization (WHO) in its constitution in 1946, when health was defined as the state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being, and not just the absence of disease (WHO, 1947). This definition of health points to the intersecting domains of life (biological, social, political, cultural, and environmental) that work together in complex ways to produce the health of individuals who form populations. Models of health, such as the Healthy People 2010 determinants of health (see Figure 1.1), present the multiple parts of the system of health and help us understand the interrelationships among those parts. With models of health we can consider and address the various factors influencing the health of individuals and groups. Broadly understanding how communities maintain or promote health will assist us in adopting the public health interventions that are most likely to reduce or eliminate community populations' exposure to risks and improve their overall health status.

Figure 1.1 Healthy People in Healthy Communities—A Systematic Approach to Health Improvement

Source: HHS, 2010a, p. 6.

In the Healthy People model of the determinants of health, it is clear that health is contingent on more than individual biology or behavior. Current efforts to reform the health care system center on the issues of health care access, quality, and cost. However, physical and social environments are also important determinants of health, including the educational and income-earning potential of individuals. The policies implemented through legislation and the interventions to achieve policy goals that public health agency leaders and their staff select are also key in determining the health status of populations. Failure to enact the policies and interventions with the greatest likelihood of improving population health, evidence-based practices, can have dire consequences for communities if health outcomes decline as a result. A population-centered approach to health aims to improve health for all members of a population and reduce health disparities among segments of that group. Many experts and practitioners in public health are concerned about the lack of emphasis on population-centered policies and initiatives to promote health and reduce risks, such as laws that mandate the use of seat belts and control tobacco, and about the perpetuation of a system of personal health care services that are overly disease focused.

Intersectoral Public Health

The 2002 IOM definition of public health states that an organized effort is deemed essential for reducing risk and promoting healthy conditions in which people can experience improved quality of life. The absence of an organized societal effort to address identified risk factors that are connected to poor health is a barrier to progress on the front lines of improving the health of communities. Tobacco use, inadequate physical activity, poor diet, and excessive alcohol use cause many of the illnesses, disabilities, and early deaths attributed to chronic diseases. These are great challenges for a local public health system that is in disarray, and in which efforts to improve population health in a community or region show little signs of coordination across the various practitioners of public health. Relatively little coordination occurs across the various sectors working on public health to address the major health issues of our time—chronic and infectious diseases, tobacco use, poverty, environmental pollution, and man-made and natural disasters. Minimal integration of the delivery of personal health care, community health services, and environmental health services by a local public health agency reduces the effectiveness of that agency in preventing risk factors that contribute to common health problems, such as chronic illnesses. Recent assessments of the performance of some local public health systems revealed a number of serious deficiencies and indicated that little progress had been made over recent decades to provide the essential public health services (Brooks, R., Beitsch, L., Street P., Chukmaitov, A., 2009; Smith, T., Minyard, K., Parker, C. Valkenburg, R., and Shoemaker, J., 2007; FL DOH, 2005). Gaps continue to be found across local public health systems in the performance of the essential public health services, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC, 2008b) report that no state is completely prepared to respond to a major public health threat. A National Association of County and City Health Officer's (2010) profile study of over 80 percent of local public health agencies (LPHAs) in the USA revealed that from 2005 to 2008, immunizations were the most stable service category in LPHAs and population-based primary prevention services were the least stable service group.

The complex health problems on which public health systems are focused require interactions across the multiple sectors of society contributing to health outcomes. Public health experts and practitioners have worked together to identify the main sectors of society that have a role in promoting health—governmental public health, mass media, academia, business, communities, and health care institutions (IOM, 2002). Together these multiple players and disciplines form local public health systems, which have the potential to coordinate services and have a powerful impact on the challenging health problems in the world today.

Local public health agencies, also known as local health departments, are located in most counties or regions in the United States and are the primary government entities with the statutory responsibility for protecting and promoting populations' health. Local public health agency workers help form the backbone of a local public health system and are skilled in multiple disciplines, including epidemiology, surveillance, laboratory testing, health education, environmental health, and medicine. State public health offices or departments exist in every state in the nation. The national arm of public health is present in the Department of Health and Human Services, which houses the CDC, along with the Health Services Research Agency, the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, and the National Institutes of Health.

As mentioned already, health care providers are important partners in promoting the public's health. For decades, the Internal Revenue Service has required nonprofit hospitals to report community benefit expenditures that improve community health status and reduce the burden for individuals of diseases and injuries that increase health care costs (Barnett, 2009). Community benefit was defined in a 1983 ruling by the Internal Revenue Service as the promotion of health for “a class of persons sufficiently large so that the community as a whole benefits.” The ruling called for nonprofit hospitals to be more proactive in improving health at the community level—a population-centered approach—and legislators and policy experts are now requesting that nonprofit hospitals play a more strategic role in allocating resources for improving health in local communities (Barnett). Beginning in 2010, new Internal Revenue Service requirements for nonprofit hospitals have led to major revisions in the form used to account for tax-exempt status and charitable activities.

The Public Health Institute and a diverse group of hospitals have developed uniform standards for community benefit programming and reporting, promoting charitable activities beyond the traditional emergency room and in-hospital charitable care widely reported by tax-exempt health care organizations. The Association for Community Health Improvement, part of the Public Health Institute, is working with seventy hospitals to develop standards and guidelines for accomplishing community health improvement (Association for Community Health Improvement, 2006). The initiative is focused on three goals:

1. Reducing health disparities

2. Reducing health care costs

3. Enhancing communities' problem-solving capacity for addressing health issues

A myriad of other national and local organizations also provide public health services to promote and improve the health of populations. The American Cancer Society, the American Heart Association, the American Diabetes Association, the Public Health Foundation, the American Public Health Association, community health care providers, and local community churches and civic groups are all examples of organizations that provide some level of public health services and contribute to the mission of public health. Evidence is accumulating concerning the important contributions to the public's health that such private organizations make. However, determining these contributions' effect on public health services and outcomes requires further examination of the nature and intensity of these relationships (Mays et al., 2009).

Although the U.S. public health system has multiple organizations working fairly independently to achieve better health for their own constituents, there are notable examples of partners in the system working together successfully to address population health issues. For example, local, state, and national public health organizations, in partnership with the American Cancer Society, community groups, and other government agencies, successfully reduced tobacco use in California, Massachusetts, Florida, and elsewhere through policy changes, social marketing, and tobacco cessation services. Further, the number of tuberculosis cases in the United States sharply decreased by an average of 7 percent each year from 1993 to 2000, in part due to private and public partnerships among government entities; the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute; the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation; and the American Thoracic Society. Such examples demonstrate the power of an effective public health system in which public health services are coordinated across multiple organizations to improve community health outcomes.

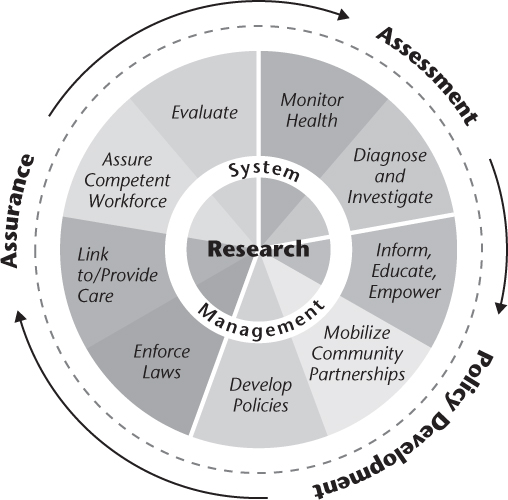

Public Health Services

Many public health leaders have accepted and promoted the 2002 IOM definition of public health as the official mission of public health; however, public health organizations, stakeholders, and community groups are still unclear about the type and scope of services public health organizations should be performing to improve the nation's health. The IOM's earlier report (1988) on local public health systems named the following core functions of public health: assessment, policy development, and assurance. The core functions were further described in terms of the ten essential public health services (see Figure 1.2). Assessment embodies the important services of monitoring health status to identify health problems, and diagnosing and investigating health problems and hazards in a community. Policy development includes informing, educating, and empowering people about health and potential actions they can take to stay healthy; mobilizing and organizing communities to identify and address health issues; and finally developing policies or procedures to support healthy communities. The function of assurance entails enforcing public health laws and regulations that protect the community's health; linking people to needed health services; making sure there is a competent workforce for the delivery of public health services; evaluating the effectiveness and quality of public health programs and activities; and conducting the necessary research to build a better, more responsive, and effective public health system.

Within the local public health agencies, the essential services are posted on walls, but public health leaders continue to openly question how they can market these core functions to their stakeholders. The underlying issue is how to implement the ten essential services when principal funding to local public health agencies is not designated for core functions that are so broad in scope. The revenues local public health agencies receive are primarily categorical, and are designed to support such separate programs as family planning, maternal and child health, immunizations, tuberculosis screening, and water safety. Improving the competencies of the public health workforce in the areas of assessment, assurance, or policy development has been hampered by funding streams designed to support more specific services, such as tuberculosis screening and treatment or maternal services.

Public Health's History and Its Impact on Current Services

A brief history of public health in the United States provides some insights into the evolution of the mission of public health and the ever-changing scope of services delivered by government public health agencies, primarily in response to the many demands from various sectors of society. This historical review can help us understand the context in which the mission of public health has been defined over the past 150 years and the lingering uncertainty about the purpose and services of public health organizations as part of the larger U.S. public health system. Understanding the historic roles and services of public health entities will provide a foundation for considering the transformations public health organizations must make to deal with old and new risk factors affecting the current health of the U.S. population.

Among the earliest pioneers in assuring conditions that would keep the public healthy was John Snow, an Englishman who linked an outbreak of cholera in London in 1854 to well water drawn from a public pump. His historic work in detecting the root causes of the disease was instrumental in controlling the spread of cholera and protected hundreds of people from the fatal disease. As one of the earliest practitioners of public health, Snow defined a role for public health in the identification and control of potentially fatal communicable diseases. Louis Pasteur's discovery of pathogenic bacteria in France in the 1860s, along with Robert Koch's work in Germany in the 1870s, led to the birth of the new science of microbiology. Further, the study of parasites and the development of immunology gave public health professionals the tools they needed to understand the spread of disease and how to prevent it using vaccines. What is more, the advent of biomedical science was particularly important to the ongoing colonization and economic development of the tropical world by Europeans: guided by the principles of microbiology, they were able to partially or completely control the insect vectors of such debilitating diseases as yellow fever and malaria.

Public health professionals today offer services that include promoting safer sources and distribution of water and foods through inspection and enforcement programs; developing and providing immunizations; and surveying and controlling dangerous infectious diseases, such as malaria, tuberculosis, syphilis, HIV/AIDS, hepatitis, influenza, and SARS. The public by and large attributes the success of disease control to the health care treatments that evolved from the biomedical sciences. The services of a public health agency to prevent diseases in the first place or identify and control emerging diseases through systems of surveillance, inspection, enforcement, and quarantine or isolation are not widely known to—or understood by—the general public. Visits to the doctor or to the local public health agency to receive care that restores an individual's health after the onset of disease or injury are more familiar to the average community resident. We have observed, however, that awareness of the role of local public health systems to prevent disease increases during times of large outbreaks or pandemics, like the 2009 H1N1 pandemic.

Following in Snow's footsteps, Edwin Chadwick led a sanitary movement at the end of the nineteenth century in England that created an official role for the government in maintaining sanitary conditions, thereby protecting the public from disease. Lemuel Shattuck's Report of the Sanitary Commission extended Chadwick's ideas and proposed a system of state and local public health agencies that would contend with communicable diseases, conduct sanitary inspections of foods and water systems, collect and provide information on births and deaths, and offer services to children (Turnock, 2009).

Charles-Edward A. Winslow, a public health leader during the early twentieth century, defined public health as the “science and the art of preventing disease, prolonging life, and promoting physical health and efficiency through organized community efforts for the sanitation of the environment, the control of community infections, the education of the individual in principles of personal hygiene, the organization of medical and nursing services for the early diagnosis and preventive treatment of disease, and the development of the social machinery which will ensure to every individual in the community a standard of living adequate for the maintenance of health” (quoted in Turnock, 2009, p. 10). Winslow's definition incorporates much of what public health agencies now provide as services to their communities each day, through environmental health programs; disease identification and control; health education in clinical and community settings; and provision of medical services to prevent, diagnose, and treat primarily communicable diseases. When public health agencies become the medical homes for uninsured people, as do a number of organizations throughout the United States, they also engage in the delivery of chronic disease services that include diagnostics, prevention, and treatment. The development of a “social machinery” to ensure a health-promoting quality of life is an area in which public health practitioners require additional skills and funding. The ten essential services contain elements of the “social machinery” Winslow addresses—mobilizing communities; educating, informing, and empowering individuals and their neighborhoods; and developing policy that promotes the overall health of communities.

In the twentieth century public health services expanded to address the appalling rates of infant mortality in the United States. Local and state public health agencies developed children's programs with a focus on nutrition, health care, and school inspections to lower these mortality rates and improve the living conditions associated with social and environmental determinants of health. By the 1950s the primary services of public health agencies encompassed communicable disease control; sanitary environmental inspection and enforcement; maternal and child health services, including limited nutritional support for mothers and children; vital statistics; health education primarily associated with maternal and child health and communicable diseases; and medical care. In the United States the provision of medical care through public health agencies is confined to indigent or uninsured families (primarily women and children) and populations with certain health conditions, such as HIV/AIDS, syphilis, and tuberculosis. Many public health agencies experienced an infusion of federal primary care funds during the 1980s. They billed Medicaid along with other third-party insurers, and they successfully pursued contracts with health maintenance organizations (HMOs) contracted by state governments to manage care and costs of low-income and indigent populations covered by state Medicaid funds. Public health agencies, suffering from inadequate funding, believed that the influx of Medicaid funds would help support public health efforts and expand a safety net for uninsured families of women and children, affording them access to primary care services.

Many community residents today are familiar with the role public health agencies have played in ensuring the sanitation of the environment by inspecting restaurants and assigning sanitation scores for public review on restaurant walls. Others have dealt with their local and state public health agencies' environmental health sanitarians and engineers when installing private septic or small wastewater systems to treat and test wastewater from their homes, and have sought recommendations for systems that guarantee safe drinking water. The expansion of public health programs for women and children in the first half of the twentieth century continues today as major public health services funded by federal, state, and local revenues. Women, Infants, and Children (WIC), the federal program to provide nutritional services and food coupons to pregnant mothers and their newborns, can be found in many public health agencies in the nation. Further, many local public health agencies provide prenatal care services to indigent families to promote healthier birth outcomes. For families—primarily women and children—with little or no access to care or an inability to find a health care provider willing to accept Medicaid and lower reimbursement rates, the local public health agency has become the primary health care provider.

Gap Between Mission and Current Public Health Practice

The mission of public health of assuring conditions in which the population can be healthy is possible through a population-based primary prevention and health promotion framework. Public health services that address such conditions include community health assessments and collaborative community health improvement initiatives. In addition, national public health priorities, such as the Healthy People 2020 promotion of healthy weight for community members and reduction of health disparities, are opportunities to work locally on national initiatives to create healthy conditions. According to a national self-assessment survey of local health departments (LHDs) conducted by the National Association of County and City Health Officials (NACCHO, 2008, p. 2):

- 63 percent of LHDs had completed a community health assessment in the last three years.

- 49 percent of LHDs had participated in community health improvement planning in the last three years.

- 58 percent of LHDs supported community efforts to address health disparities.

Community health assessments examine determinants of health and health outcomes and report on the overall health status of a community. Quality community health improvement processes incorporate the assessment information into strategic plans to implement evidence-based public health services that improve identified priority health issues, such as obesity or tobacco use. Community health improvement is an effective tool for collaborating with stakeholders on a vision and plan to improve community health (IOM, 1997). The 2008 NACCHO survey demonstrates that LHDs must do more to comprehensively assess and monitor the health of the population using community health data. In addition, more work is needed by LHDs to conduct comprehensive and strategic community health improvement.

Primary Care and Primary Prevention in Local Public Health

Researchers find it very challenging to analyze the performance of local public health systems and their governmental arm, local public health agencies, given the complexity of the implementation of public health programs. There is also an absence of clarity in regard to what types of government activities constitute public health services (Sensenig, 2007). An emerging body of evidence points to the wide variation in the availability and quality of public health services across many communities (Mays et al., 2006). Researchers in Georgia, for example, found that public health services were not aligned with the essential services and core functions of public health, after examining an extensive body of literature on the practice of public health and conducting a case study on the core business of public health in the state of Georgia (Smith et al., 2007).

A growing number of public health experts have expressed concern about the focus on primary care services and treatment of medical conditions by local public health agencies. A recent study on the Florida Department of Health found that local public health agency expenditures on clinical services exceeded substantially the expenditures attributed to the provision of the core functions and essential services included in the mission of public health (Brooks, Beitsch, Street, and Chukmaitov, 2009). Since the 1950s, the public has considered the provision of medical services to indigent or low-income community residents to be a primary function of the local public health agency. At the same time, the public has only a limited understanding of the role of a local public health agency in the delivery of primary prevention services to promote population health. We can understand the basis for this public perception if we consider the programs that have received consistent funding from federal and state governments for more than fifty years: maternal and child health, screening for and treatment of sexually transmitted diseases, family planning, immunizations, and tuberculosis screening. A number of public health programs have a clinical and community focus; but the emphasis, both in the financing and staffing, is primarily clinical or medical. As discussed earlier, across the United States over the past twenty years, local public health agencies have sought new sources of funding by billing Medicaid, Medicare, and third-party insurers—further indication of the growth of medical services in the practice of public health. Evidence of similar efforts on the part of local public health agencies to secure funds for the provision of preventive health services can be found in pockets around the nation, but these attempts have not resulted in revenues and expenditures equal to those for medical services. Explanations for the disparate funding include the emphasis on medical care in the United States as well as the absence of leadership in public health agencies to advocate and secure necessary funding for the appropriate levels of public health services. Total funding for health care services and medical research dwarfs the funding for federal public health programs. Gaps in the provision of the ten essential public health services and the lack of primary prevention and health promotion activities in LPHAs are not surprising when we realize the large disparity in funding between medical and public health services.

Preparedness

Following the 2001 terrorist attacks in New York City, public health agencies received substantial increases in preparedness revenues, thereby improving their capacity to prepare for bioterrorist or chemical attacks as well as natural disasters. Beginning in 2008, however, funding for local public health agencies' preparedness programs have been declining, and their ability to respond effectively to a natural or man-made disaster, such as climate change, is doubtful. The U.S. General Accounting Office concluded in 2004 that “no State is fully prepared to respond to a major public health threat” (quoted in Kinner and Pelligrini, 2009, p. 1780). The CDC (2008b) recently came to the same conclusion.

Public health agencies in parts of the nation have been preparing and responding to natural disasters, including hurricanes, fires, and flooding, for at least two decades. The Florida Department of Health was commended for its 2004 responses to five major hurricanes that ripped across the peninsula. However, public health's lack of preparedness was front-page news in 2005 when Hurricane Katrina flooded New Orleans and devastated hundreds of communities along the coastal areas of Louisiana and Mississippi, killing over 1,800 people. This disaster clearly revealed that most aspects of the response, including the local public health system's actions, were inadequate, disorganized, and insensitive to the dangerous risk factors that people living in poverty, primarily African Americans, were facing. In New Orleans, thousands were stranded after the evacuation order. The risks from the heat, floodwaters, and other elements, combined with existing social disparities in health, contributed to an exacerbation of chronic health conditions and distrust of government agencies. More health risks evolved when thousands of people, evacuated from their homes, were exposed to dangerous chemicals in the trailers used to house the homeless, in which the indoor air tested positive for formaldehyde.

As we count the achievements in public health during the twentieth century, among them vaccinations, enhanced motor vehicle safety, control of infectious diseases, safer workplaces, safer food supply, family planning, and more, we must also assess the ways in which local public health systems and public health agencies can operate at levels of quality to achieve the mission of public health—ensuring the conditions in which people can live healthy and happy lives.

Future Public Health Services

People living in many countries throughout the world are healthier today than they were a century ago. Public health initiatives during the past one hundred years have been instrumental in improving living conditions in communities through cleaner water, food, and air; the use of sewage systems to safely handle wastewater; better nutrition; immunizations; and expanded education concerning the behaviors and risk factors that contribute to poorer health and preventable injuries. Public health practitioners now find themselves and their organizations faced with complex and seemingly insurmountable health problems, such as obesity and the effects of global climate change. Obesity, for example, will require new capacities and skills to reverse the increasing rates of early-onset diabetes and cardiovascular disease in young adults. In the meantime, what some believe is the failure of the U.S. public health system to prevent the obesity epidemic is actually an opportunity to learn from experience and begin applying public health practices with the greatest likelihood of improving health outcomes and reducing exposure to risks. By providing primary prevention services and attending to the social, environmental, and behavioral aspects of health, public health practitioners play an important role in reducing the occurrence of diseases and promoting healthy living conditions.

Joseph Juran, a twentieth-century quality management and improvement scholar and author of several books on quality, is well known for the axiom that every system is perfectly designed to achieve exactly the results it gets (cited in Berwick, James, and Coye, 2003). The phrase is powerful for leaders seeking improvement in public health, as it states the obvious fact that to attain a new level of performance, there must be a new system. A redesign of local public health systems would signal an intention to refocus on the mission of reducing risk through primary prevention strategies—in other words, directing the resources of the U.S. public health system on mitigating events that create risk and thereby reducing our exposure to those risks. What would be the characteristics of redesigned local public health systems, and what role would local public health agencies play in this system redesign?

Multiple conceptual guidelines or standards are available to direct the comprehensive redesign of the U.S. public health system. The CDC launched the National Public Health Performance Standards Program in 1998, and released the first assessment instruments in 2002 to assess local public health systems; state public health systems; and local boards of health, the governing bodies for many local public health systems in the United States (CDC, 2008c). The CDC designed the local public health system performance standards instruments to assess the performance of the ten essential services. The local public health system assessment was specifically developed to include the local public health agency, as well as other intersectoral partners in the community working on public health issues and contributing to the mission of public health. The latest reports from the CDC show that twenty-one states have completed the state public health assessment, ten states are actively using the local public health system instrument, and five states are using the local instrument at a moderate level (CDC, 2008c). Very little research is available on the impact of the use of these performance standards instruments on the implementation of local public health programs, or on whether conditions that promote the health of populations have improved. Because LPHAs are unable to account for either their work or their funding in terms of the ten essential services, the use of standards based on the ten essential services framework may not be feasible for LPHAs.

Ethical Practice of Public Health

The Principles of the Ethical Practice of Public Health (Public Health Leadership Society, 2002) makes explicit the ideals of the local public health institutions that serve communities and, if enforced, promotes accountability of those institutions to perform according to the principles outlined in this Public Health Code of Ethics (see Exhibit 1.1). The Code asserts the primary prevention mission of public health by explicitly stating that public health should address the “fundamental causes of disease and requirements for health.” The Code emphasizes that the health of individuals is connected to their community life, and maintains that community health is to be achieved in a manner that respects individual rights, advocates for the empowerment of community members who are disenfranchised, and informs communities using the available and pertinent information they need to make decisions related to policy and program choices. Many working in public health are familiar with the Public Health Code of Ethics; however, its effect on public health system or agency performance has been minimal.

Exhibit 1.1: Principles of the Ethical Practice of Public Health

1. Public health should address principally the fundamental causes of disease and requirements for health, aiming to prevent adverse health outcomes.

2. Public health should achieve community health in a way that respects the rights of individuals in the community.

3. Public health policies, programs, and priorities should be developed and evaluated through processes that assure an opportunity for input from community members.

4. Public health should advocate and work for the empowerment of disenfranchised community members, aiming to ensure that the basic resources and conditions necessary for health are accessible to all.

5. Public health should seek the information needed to implement effective policies and programs that protect and promote health.

6. Public health institutions should provide communities with the information they have that is needed for decisions on policies or programs and should obtain the community's consent for their implementation.

7. Public health institutions should act in a timely manner on the information they have within the resources and the mandate given to them by the public.

8. Public health programs and policies should incorporate a variety of approaches that anticipate and respect diverse values, beliefs, and cultures in the community.

9. Public health programs and policies should be implemented in a manner that most enhances the physical and social environment.

10. Public health institutions should protect the confidentiality of information that can bring harm to an individual or community if made public. Exceptions must be justified on the basis of the high likelihood of significant harm to the individual or others.

11. Public health institutions should ensure the professional competence of their employees.

12. Public health institutions and their employees should engage in collaborations and affiliations in ways that build the public's trust and the institution's effectiveness.

© 2002 Public Health Leadership Society, p. 4.

Definition of a Functional Local Public Health Agency

In 2005 a diverse group of public health practitioners and national public health organizations developed the “Operational Definition of a Functional Local Public Health Agency” (Lenihan, Welter, Chang, and Gorenflo, 2007). This attempt to clearly articulate the standards of achievement for the government entity of a local public health system—the local public health agency or local health department—was an offshoot of the CDC's National Public Health Performance Standards Program. Local public health officials wanted a set of standards that applied directly to their organization, considering the scope of the ten essential public health services to be quite broad and applicable to the wider array of community groups contributing to the mission of public health.

The operational definition is hailed by some as the next step in a chain of events over a twenty-year period to clearly define a shared understanding of what community members can expect from their local public health agency—no matter where they live (Lenihan et al., 2007). The definition is also based on the ten essential services and includes forty-five standards to help local public health practitioners define themselves in common terms and identify concrete areas for improvement of community health status. So far, little has been reported about local public health agencies' use of the operational definition. This initiative to drive changes in the practice of public health by LPHAs may experience the same relatively low level of use as the national performance standards, given the ten essential services framework on which the operational definition was based.

Accreditation

In 2007 the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation provided support for the establishment of the Public Health Accreditation Board (PHAB). PHAB works closely with national public health associations—the National Association of County and City Health Officials, the Association of State and Territorial Health Officials, and the National Association of Local Boards of Health—in the quest to accredit public health agencies. PHAB is a voluntary public health accreditation program, launched with the mission of advancing the quality and performance of local public health agencies. Beta testing of the state and local accreditation standards commenced in late 2009, with a planned implementation of a voluntary accreditation process in 2011. These standards were generated, in part, through a review of the “Operational Definition of a Functional Local Public Health Agency” and the CDC's National Public Health Performance Standards Program. The initial set of PHAB standards assesses the administrative capacity and governance of an agency, and the agency's ability to perform the ten essential services. Capacity, process, and outcome are all measured as part of the accreditation process. The Public Health Accreditation Board will award a local public health agency with accreditation based on its self-assessment using the standards instrument, a site visit report from the accreditation board, the agency's response to the site visit report, and the testimony of accreditation board staff (Public Health Accreditation Board, 2010).

Many in the field of public health are optimistic about the role of accreditation in bringing about needed changes to the practice of LPHAs. In this era of economic downturns, some experts in public health contend that accountability of LPHAs through an accreditation process will potentially bestow financial advantages for these agencies as they compete for shrinking resources with other government entities (Betisch and Corzo, 2009). Other public health professionals question the assertion that accreditation can lead to accountability and improved population health when the basis of accreditation centers on an agency's ability to perform core functions that are not clearly linked to health outcomes (Wholey, White, and Kader, 2009, p. 1546): “Currently most measures are process measures…. [Q]uality improvement efforts should demonstrate not only process improvement, but should also be linked to public health goals and overall improvements in population health outcomes.” Little evidence exists to support a causal link between accreditation and population health outcomes, calling into question the push to spend limited public health resources on periodic accreditation programs. Helping public health agencies understand and implement population health services based on evidence through education programs and technical assistance is another area of weakness in the system that could be strengthened. Such efforts compete for limited public health resources. Clearly, the jury is still out on whether an accredited health department does better in improving health in the community it serves (Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, 2010).

Quality Characteristics of a Well-Functioning Local Public Health System

Local public health agencies and local public health systems are struggling to realize the mission of public health. New levels of performance are possible only through an extraordinary system-level redesign, achieving the goal of an idealized system that reaches new levels of improvement (Moen, 2002).

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services in 2008 led an initiative to redefine quality in the practice of public health. This group of experts and experienced public health practitioners defined quality in public health practice to be “the degree to which policies, programs, services, and research for the population increase desired health outcomes and conditions in which the population can be healthy” (HHS, 2008). The group defined a set of quality characteristics of a well-performing local public health system, which are presented in Exhibit 1.2.

Exhibit 1.2: Quality Characteristics to Guide Public Health Practice

- Population-centered—protecting and promoting healthy conditions and the health for the entire population

- Equitable—working to achieve health equity

- Proactive—formulating policies and sustainable practices in a timely manner, while mobilizing rapidly to address new and emerging threats and vulnerabilities

- Health promoting—ensuring policies and strategies that advance safe practices by providers and the population and increase the probability of positive health behaviors and outcomes

- Risk-reducing—diminishing adverse environmental and social events by implementing policies and strategies to reduce the probability of preventable injuries and illness or other negative outcomes

- Vigilant—intensifying practices and enacting policies to support enhancements to surveillance activities (e.g., technology, standardization, systems thinking/modeling)

- Transparent—ensuring openness in the delivery of services and practices with particular emphasis on valid, reliable, accessible, timely, and meaningful data that is readily available to stakeholders, including the public

- Effective—justifying investments by utilizing evidence, science, and best practices to achieve optimal results in areas of greatest need

- Efficient—understanding costs and benefits of public health interventions and to facilitate the optimal utilization of resources to achieve desired outcomes

Source: HHS, 2008.

As we have already stated, ensuring conditions in which people can be healthy is the primary mission of public health. The overwhelming prevalence of preventable chronic diseases is in part a reflection on the choice organizations practicing public health have made to adopt a predominantly disease-focused approach, avoiding the less familiar areas of the social, policy, and environmental determinants of health. A quality public health organization, or any group with a public health focus, must be

- Population-centered

- Working on inequities that are attributed to a population's demographics, such as those pertaining to race or gender

- Promoting health and reducing exposure to risk factors that are known to cause disease or injury

- Delivering services or developing policies that are based on evidence or the best available knowledge in the field

The Guide to Community Preventive Services is a resource created by a task force of experts selected by the CDC that presents evidence-based recommendations and findings for public health services (Community Guide Branch, n.d.). The Community Guide is based on scientific reviews of studies that have demonstrated what does and does not work in reducing exposure to risk factors known to cause disease or injury, promoting protective factors that contribute to health, and improving health outcomes. Although the Community Guide is far from complete, it presents a good starting place for finding evidence-based, population-centered interventions to address such health issues as obesity, physical activity, tobacco use, nutrition, adolescent health, asthma, HIV/AIDS, motor vehicles, and more. For example, community-wide campaigns to increase physical activity are interventions that are recommended (Community Guide Branch).

Public health agencies conducting evaluation research in connection with current and future interventions are operating effectively and can make significant contributions to the growing body of evidence found in the Community Guide (Community Guide Branch, n.d.) and similar publications. Ongoing efforts by public health agencies to evaluate population-centered services will add momentum to the establishment of more evidence-based public health interventions that are aligned with the mission of public health. Conducting evaluation research and reporting on findings are characteristics of an efficiently functioning local public health system and local public health agency. Accountability and transparency must also define the local public health systems and agencies of the future. A quality local public health system measures and reports on performance to determine if strategies undertaken in the interest of community health actually led to improvement. Only by studying the effects of interventions to reduce risk and promote health in a variety of settings and across multiple public health organizations can we continue to build the public health evidence base and spread the knowledge of what works to improve population health.

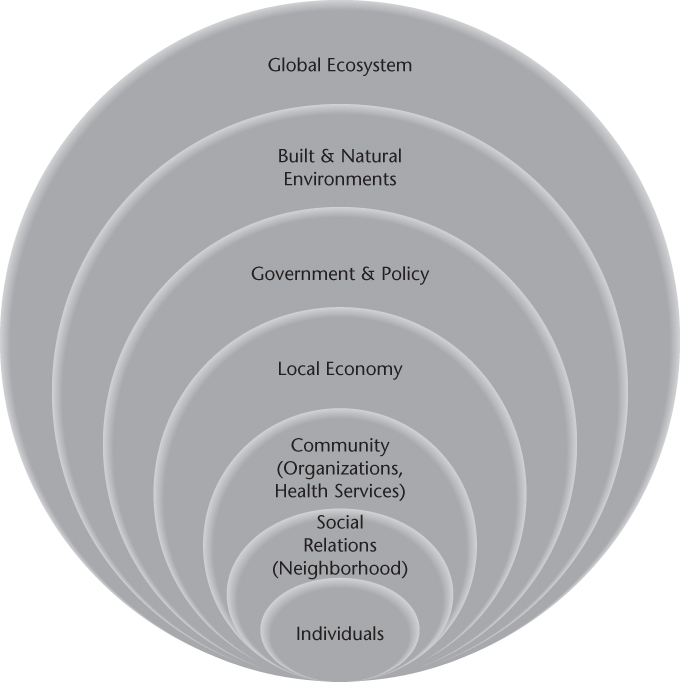

Ecological Model to Improve the Quality of Public Health Services

Along with expanding our view of quality within the practice of public health, we must also concern ourselves with the shifts in our ecosystem, such as climate change, that are predicted to have devastating effects on populations worldwide. Newer models of health are emerging that incorporate ecosystems and the natural and built environments. Behind these newer models is the belief that sustainable use of finite resources is a major determinant of health (Griffiths, 2006). Reintegrating ecosystems within the models of health draws attention to the importance of ecosystems in connection with human well-being, health promotion, and disease prevention. Figure 1.3 presents an alternate ecological model of health, including domains similar to the determinants of health and well-being presented in Figure 1.1 and the additional domains of the global ecosystem and the built and natural environments.

Figure 1.3 Ecological Model of Health

The effects of the built environment and man-made pollution on the natural environment present new challenges that add to the burden of existing and unaddressed health problems facing the United States. The practice of public health must continue to evolve beyond the current state of personal health care, communicable disease control, and enforcement of environmental health laws. The field of public health must expand the delivery of population-centered health services and apply an ecological, population-centered focus when dealing with complex problems. Using an ecological, population-based approach to improving community health requires us to consider simultaneous changes in multiple dimensions of the ecological model of health shown in Figure 1.3. Healthier communities are possible when policies are enacted that reduce exposure to harmful risk factors, for example, increasing sales tax on tobacco purchases or requiring restaurants and school cafeterias to reduce unhealthy and nonnutritious ingredients in meals. Public health partnerships to reduce crime and discrimination and promote neighborhood recreational sites for social interaction and physical activity suggest further examples of public health services that address multiple components of the ecological model of health and possess the quality characteristics of being evidence-based and population-centered. Unhealthy choices, adverse environments, and increased exposure to risk factors that harm health work together to create unhealthy communities and perpetuate racial and socioeconomic inequities. Population health deteriorates when communities must live with contaminated water, air pollution, or food deserts in which the absence of grocers or fresh food markets seriously limits the quality of foods residents can purchase. The mission of public health to promote conditions in which people can be healthy is achievable when practitioners of public health work in all dimensions of the ecological model of health in partnership with others that have a stake in assuring healthy communities. Local public health agencies must redesign themselves to focus more on evidence-based, ecological, population-centered services and less on the clinical aspects of care in order to achieve community health improvement goals.

The current practice of public health in the United States remains in disarray, operating in a nonintegrated manner, and with a wide variation in the availability and quality of essential public health services. Multiple organizations contribute to the mission of public health; however, the primary focus continues to be detecting and controlling diseases, ignoring the wider determinants associated with the social and physical environments that improve or inhibit health. The public health organization of the future will help determine the health of a population by operating within and across the many organizations forming a local public health system, integrating the practice of public health into each domain of that system. At the same time, the intersectoral public health practitioner will promote and implement evidence-based, population-centered public health services with roots in the current ecological model of health, incorporating ecosystems and the natural and built environments. Increasing the capacity to perform public health services that are clearly linked to the mission of public health and to the quality characteristics is achievable by engaging multiple community partners, including health care organizations, with community health improvement goals and securing adequate resources to rebuild our U.S. public health agencies and system.

Community benefit

Core functions

Determinants of health

Evidence-based public health practice

Health

Local public health agency (LPHA)

Local public health system

Mission of public health

Population

Population-centered

Primary prevention

1. What types of services do public health organizations provide?

2. Explain why the provision of primary prevention services is critical to improving population health.

3. Describe the gap between the mission of public health and current public health practice.

4. What are the advantages of an intersectoral approach to addressing public health issues?