Introduction

Schools are built, they are maintained, they are adapted and added to, they are demolished and they are rebuilt. Many schools will find themselves in buildings which they had no hand in designing, so they need to constantly review their estate to understand how they can get the most from it. Successful schools will be looking at every aspect of their resources to make sure they are using them to best advantage in support of their strategic goals. Their buildings are one of a school’s major resources, alongside its staff and students, and good schools will make sure that the effectiveness of the learning environment is part of that ongoing conversation.

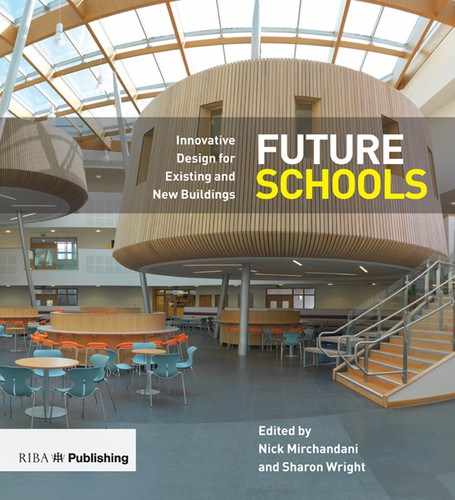

Christ’s College in Guildford (DSDHA) is a 700-place Church of England School where one front door welcomes all pupils, staff and visitors into the central atrium, creating a strong focus for the school community and embodying a vision of the school as ‘one house’ with spiritual and pastoral values.

Most schools will not be lucky enough to receive large-scale capital investment in the near future. Even those that have been rebuilt or remodelled may find that five or ten years later they need to modify their spaces to cater for changes in educational delivery. This chapter is about adapting to thrive – making the most of the spaces we have and constantly questioning and reviewing what can be done to improve them with limited resources. Whatever the circumstances, the ability to adapt and change has the potential to bring new energy and, if that energy is channelled positively, there is always something somewhere that can be improved as a result.

Most teachers and students are skilled at making do with the space and equipment that they have. It is easy to forget that the buildings we know well are flexible and can be adapted, and that making a few simple alterations to the learning environment could fundamentally improve the student and staff experience.

A building project, however large or small, can accelerate the normal pace of change. It is an opportunity to question the usual way of doing things and to take control of shaping the environment and its relationship to learning. Even if major capital works are not planned, or budgets are limited, reviewing how the building works, and what can be done to improve it, can begin a conversation with staff and students about ways of working that can be productive and empowering.

What makes change happen?

The impetus for change to the physical environment can come from many sources – some are imposed from outside and some come from within the school community. Being aware of the source of the change will assist in accommodating it and benefiting from it. Here are a few of the major sources of change and examples of their possible impact:

- Government policy: Free school meals for all, infant age children could require a new kitchen and an expanded dining area.

- Evolving learning practice: New technology in the classroom could result in a whole new style of learning experience which needs changes to the type and layout of furniture in the classroom.

- Local circumstances: A rise in pupil numbers could equate to a need for additional classrooms; competition from other schools could require improvements to the school grounds to provide unique learning opportunities and enhance the image of the school.

- Routine cycle of change: Building maintenance could be an opportunity to refresh the colour scheme and thereby the character of the interior or exterior of the school.

- Evolution of the school as an institution: Taking on pupils of a different age range or adopting a new specialism. Both of these could result in a new teaching block or an extension and the need to adapt external areas.

- New headteacher: The new head could bring a change in pedagogy such as team teaching, which requires the ability to combine a group of classrooms. Alternatively, the new head might want to change the school’s relationship with parents, which could result in upgrading the front entrance or renewing the reception area.

As well as these external drivers, schools also have the opportunity, as part of their annual strategic planning process, to regularly review their estates and identify where change is needed. Being proactive rather than waiting for change to be imposed from elsewhere can create momentum and energy, and a real sense of ownership.

Ten tips for embracing change and getting the best from it

Once a school has identified that change is necessary, what should it do to make sure it gets the best from the process? What can design teams offer their clients so that even small projects are part of a long-term process for managing change? Here are some suggestions for maximising the opportunity:

1 Have a big picture masterplan that encompasses educational changes as well as physical change.

It is unusual to have sufficient funding to completely revolutionise the entire teaching and learning environment in one sweep. It might be necessary to progress in small stages as money becomes available and holiday periods provide the opportunity to carry out construction work. An overall masterplan will set out the large-scale ambition so that smaller projects can be seen as pieces of a larger whole.

The masterplan could be commissioned from the design team as a stand-alone piece of work. They will look at the existing buildings and consider their future potential. A range of options can then be drawn up to explore what the final outcome could be and how best to get there. Some existing buildings may only need a light refresh, they could be reconfigured into a different use or they may be near the end of their useful life and not warrant significant investment. Sometimes there may be difficult decisions. For example, a relatively new part of the school may be preventing the realisation of a larger scale redesign that would bring significant benefits to pupils.

The masterplan should also include educational aspects such as the wish to offer a new subject, or a move to mixed age tutor groups.

Learning happens in every space in the school. As well as the core curriculum, pupils also learn how to be friends and how to work, play and eat together. The masterplan needs to consider all of these aspects of school experience and how they could be positively affected by change.

It is important to articulate the less tangible outcomes that are desired, even if they don’t seem to be directly quantifiable. These could be a desire for calmer circulation areas so that the school day is less stressful, or an increase in staff satisfaction, or a drop in reported incidents of antisocial behaviour.

2 Break the big plan into manageable steps.

Only Superman can leap tall buildings in a single bound – ordinary people have more success in taking on a challenge one piece at a time. It is therefore advisable to break the big vision for physical and educational change into manageable steps, each with a clear brief and desired outcome.

The physical masterplan is likely to be organised into delivery phases so the construction happens one stage at a time. If educational change is also planned, it is valuable to rehearse the pedagogic or organisational change in the old buildings first. Alternatively it may be preferred to configure the new buildings so that they reflect the old teaching practices initially but can be reorganised later, allowing staff to adapt over time.

For instance, there may be a desire to increase interactivity and team spirit amongst staff. The long-term plan might be to create a staff work and social area but an interim arrangement could be to use a particular classroom for an hour after school to encourage teachers to do their preparation together rather than working alone in their department or at home.

As another example, the headteacher might want to introduce project-based learning for the whole school. It is envisaged that this will need open-plan workshop areas with enough space to brief a whole year group and side rooms for smaller group tutorials. This configuration could be set up in one part of the school for trialling and training before being implemented further.

Investing time early on to consider the options and plan how the school will manage during construction is extremely valuable. Everything will then be ready when intense engagement is needed.

3 Decide who is in charge and empower them.

There is no substitute for good leadership in ensuring the long-term success of a project. Often the headteacher will be the person who leads change but it could be a deputy head or an active governor. If the change leader is not the headteacher then they must be given clear authority for the role so that they can gain the trust of all the other parties involved and be able to deliver effectively.

It is very difficult to lead and participate in change at the same time as doing a day job and the nominated project leader will need to be released from some of their normal duties. This could require additional support being drafted in or low priority tasks being slow-tracked to free-up time.

Schools have a cohort of people who are involved in the day-to-day leadership and management of the institution including governors and academy sponsors. Managing the leaders requires deliberate effort so that they feel involved in setting direction and decision making but are confident to allow the project leader to get on with the job.

The same advice can also be given to the design team. Decide who is going to be the lead client contact and ensure that they are aware of how all aspects of the design are developing. This doesn’t mean that no other member of the team ever talks to the school. It does mean that the ambition is to create a well thought-through scheme in which all the various aspects work together to deliver an efficient solution to the client’s needs.

Even the most persuasive person can meet with some resistance – sometimes justifiably. Within discussions it will be necessary to be clear about what is negotiable and what isn’t. Strong leadership is important but be ready to adapt if unforeseen circumstances require it.

4 Create and sustain momentum.

Sometimes it can be hard to get things moving. People want to stay in their comfort zone and see no reason to do things differently. Refuseniks need to be convinced as to how change will benefit them. It might be difficult to identify an individual advantage however and the positive impact on the larger community may need to be cited as the desired outcome.

Good change is viral – once started it can take on a life of its own. This effect can be positively harnessed by creating a cadre of change agents within the school, who themselves are early adopters, and will demonstrate and explain the change to their peers. This can help to accelerate and embed the change so that it is more likely to stick.

Once a new configuration seems to be established, ongoing support will be needed to ensure that the change is permanent.

5 Plan communications.

The person with the job of leading change will need to make sure that everyone else, including all staff and governors, understands what is happening and the expected result. It is helpful if the explanation of the change can take the form of a compelling vision in which everyone can see his or her place in the brighter future.

Physical change can seem quite slow. Regular communication is important even if there isn’t much happening. If no news is forthcoming, people may invent their own which can be detrimental to the success of the project. Regular communication will also help to build up trust so that when a burst of activity occurs, such as work starting on site, the school community will be able to keep calm and carry on as required.

6 Get help with what you don’t know.

No one can be expected to know everything. The design team won’t be able to teach a class of nine year olds for a term and teachers may not be able to visualise three dimensional space from a two dimensional plan. For non-architects, drawings, models, furniture samples etc. can be very helpful in visualising the physical changes proposed and considering what their impact will be.

Visiting other projects is also very worthwhile. Imagining something different from day-to-day working experience is not easy and seeing a fully realised alternative can assist people in making that mental leap. These visits can be used as a way of engaging staff, starting a dialogue and helping the design team understand what is wanted.

For the design team, spending some time in the school during a normal day is powerfully informative. It is also important to understand the major events that happen in the school year such as exams, special study weeks that require a different timetable, or festivals.

7 Pay attention to the invisible.

Some of the most important aspects of a good learning environment can’t be seen. A room’s temperature, ventilation and acoustic qualities make an enormous difference to people’s comfort and ability to concentrate, communicate and learn. A building can be the most beautiful place imaginable but if it’s too hot, or the echoey acoustics means there is a constant din, then it can’t be considered to be a good design.

The heating, lighting and ventilation will also make a significant contribution to the cost of running a school long term so it’s very important that they work harmoniously and efficiently. The electricity used for lighting is often the largest item on a school’s energy bill.

Describing these aspects of the design as invisible is rather misleading. The strategy for thermal comfort, lighting and acoustics will have a big impact on other parts of the design such as the size and type of windows, floor to ceiling height and the depth of classrooms.

For instance, if a space that was a staff room is to be used for teaching, then the acoustics will probably need to be softened with the addition of more absorptive surfaces such as curtains, carpets or sound absorbing panels to the walls. These can make a huge difference to the usability of a space.

The long-term masterplan for a school might show the teaching spaces arranged in different configurations as the years go by. The heating and ventilation design will need to be able to adapt to these changes which may be straightforward if they are known from the start but much more difficult if they are unplanned. Also, if it is known that in the future a particular building is to be extended, then it is possible to build spare capacity into heating, cooling and ventilation systems from the outset. It is typically much more difficult or expensive to add these later.

8 Think long term.

Even once the initial masterplan is realised, the evolution will still continue. The decisions that will be made during a building project will affect the school for many years. It is impossible to know how education will be organised in the future but it is possible to design a building that is reasonably adaptable and can easily be extended or reconfigured. This means designing the structure, windows and building services so that internal walls could be placed in different positions. It can also mean taking care over the location of stairs, lifts and service shafts so that if the building needs to be extended, they won’t be in the way, eg if stairs are placed at the very end of a block then it may be difficult to extend in that direction.

The easiest way to make a space flexible is to build it slightly bigger than its basic use requires, although this may require manipulation of area and funding allowances. It doesn’t mean that every classroom has to be huge however – not every space can or should be a learning barn – it just needs to be big enough that the tables and chairs can be arranged in several ways and perhaps leave some open space for demonstrations.

Some shared rooms in a school are designated as multifunctional spaces. Special care needs to be taken with these because there is a risk that they do many things but none of them well. Multifunction spaces work best if the types of activity taking place there are similar, eg a room that is used for both art and science might work well because both require space and water. A room used for art and music might be less successful.

For school communities that have been used to operating out of relatively decrepit premises with poor environmental conditions, new buildings are likely to mean a complete change in the management and maintenance regime. This will be particularly true if the buildings were procured under a public-private partnership arrangement. The new buildings are likely to have more sophisticated controls for their environmental systems and different finishes may require a change in the cleaning regime.

9 Keep an open mind.

Working with other people will always bring unexpected perspectives and ideas.

The pressure on school places means that all kinds of buildings are being considered as locations for learning. This approach is encouraged by central government, which has tried to remove as many of the barriers to using existing buildings for schools as possible. It may be that radical solutions are considered as part of the project, for example, using parts of the school site or buildings that staff never imagined could be suitable for educational purposes. Or there may be discussions about new ways of delivering the curriculum, such as changes to the organisation of the school day, or making use of off-site facilities for PE.

10 Know when to stop.

The day-to-day flicker of change can make it seem that nothing is permanent and everything is in constant flux. It can appear that no decision is final and there will always be a chance for one more iteration of the design. However, building projects require some definite decisions at certain points.

Once these points have been reached and a part or all of the design has been fixed, it is very costly in terms of time, money and people’s patience if the client subsequently changes their mind.

Changing requirements mid-design is expensive; changing requirements during construction is extremely problematic and can lead to legal challenge. Avoid these situations by making sure you know exactly what’s happening and why.

Also, a school will know how much change it can deal with at any point. It may be that additional disruption is unmanageable if the school is under pressure to raise standards quickly. Adding more stress at particular times of the year, such as around SATS or GCSE exams, is also undesirable.

Conclusion

Change can be difficult, especially if it’s imposed from outside. Even when you think you’ve got there, staying changed can be difficult too. It is fine to admit that it is challenging, but can be damaging to the morale of staff, pupils and the design team if there is unrelenting negativity. Even if the change is being imposed from outside, try to look for the positives in the situation.

And just when you think you’re about to get a grip, something happens and the cycle starts again. That something could be an unexpected discovery on site, such as asbestos or poor ground conditions, which was not budgeted for and will mean that money will have to be found by cutting other aspects of the work. Or there could be a change in central policy that affects the design or funding of the project.

If this happens, all you can do is return to the beginning of this list of tips. What was the overall goal in the first place? Can the current project still move you towards that ambition, albeit in a different way or not as far? Can you achieve the educational changes, even if the physical changes are going to be scaled back? How will this new circumstance be communicated to everyone who needs to know?

If change is an inevitable part of school life, an explicit culture of continuous improvement can harness that ongoing evolution to positive effect. If staff and students are encouraged to reflect on their current practice and try out new approaches, this helps foster an understanding of how the physical environment influences and works in partnership with the school’s ethos, organisation and curriculum delivery. At that point the learning environment – however old or new it is – becomes an important strand in the school’s strategic planning, constantly being scrutinised and reviewed to ensure all users get the very best from it.