The effects of alprazolam on behavioural aggression

INTRODUCTION

These studies were a logical extension of those presented in Chapters 5 and 6. Increased aggressive responding on laboratory tasks has been found in normal volunteers after being given chlordiazepoxide (Salzman et al., 1974), diazepam (Gantner & Taylor, 1988; Wilkinson, 1985) and lorazepam (Chapter 6). Alprazolam is a newer triazolobenzodiazepine of high potency, its anxiolytic dose being 1.5 to 3mg/day. It also has anti-panic effects at higher doses, raising the possibility of enhanced ceiling efficacy (e.g. Ballenger et al., 1988). However, it has been reported to increase verbal hostility and behavioural dyscontrol in a proportion of patients (Rosenbaum et al., 1984), especially those with borderline personality problems (Gardner & Cowdry, 1985).

One study (Pyke & Kraus, 1988) indicated that hostility was more likely to occur in patients with panic disorder or agoraphobia with panic attacks with a secondary major depressive episode. In all these trials, hostility and aggression remitted after alprazolam treatment was stopped. Thus, it was appropriate to evaluate the effects of this benzodiazepine, first in normal volunteers, and then in patients with panic disorder taking part in a therapeutic trial.

Alcohol is often associated with aggressive behaviour. In our earlier study (Chapter 5), it resulted in an anti-anxiety and anti-hostility subjective response but in increased aggressive behaviour on the competitive reaction time task. As benzodiazepines and alcohol share many pharmacological actions and anecdotally the combination is believed to result in particularly aggressive behaviour, it seemed appropriate to evaluate alprazolam alone and in combination with alcohol (but only in normal subjects) under laboratory conditions.

NORMAL SUBJECT STUDY

Methods

Subjects

Subjects were recruited via advertisements posted on the institutional notice-board. They were paid for participating. Forty-eight healthy volunteers took part in the study, 24 females and 24 males. Their mean age was 23 ± 7 and the mean weight for males was 72 ± 12kg and for females 63 ± 12kg. They were allocated randomly to one of four groups with 6 males and 6 females in each group. There were no differences between groups with respect to weight, age, or drinking behaviour.

Procedure

The study was approved by the appropriate Ethical Committee and subjects gave written, informed consent. A double-blind, independent groups design was used to compare the four treatments: alprazolam (1mg) and alcohol (0.5g/kg); alprazolam (1mg) and placebo drink; placebo capsule and alcohol (0.5g/kg); and placebo capsule and placebo drink. Alprazolam or matching placebo capsule was given by mouth after the initial testing session. Alcohol was administered 45 minutes later as vodka, made up to 250ml with low-calorie tonic. Females received a slightly lower dose of alcohol (0.42g/kg) to achieve equivalent blood alcohol concentrations to males. The placebo drink consisted of 245ml of low-calorie tonic with 5ml vodka floated on the top and wiped around the rim of the glass. Subjects were allowed 15 minutes to consume their drink. They were instructed not to drink any alcohol for 24 hours before testing and to eat only a light breakfast before reporting to the laboratory. The subjects completed the first set of measures at 9.30 a.m. Further tests were carried out at 90, 150, and 210 minutes post-drug (45, 105, and 165 minutes post-alcohol). The competitive reaction time was run at 105 minutes post-drug (60 minutes post-drink).

Measures

Breath alcohol concentration

A Lion (Cardiff, UK) Alcolmeter AE-M2 was used to estimate breath alcohol concentrations as in Chapter 5.

Competitive reaction time task (CRT)

See Chapter 3. Amodification was that a total of only 19 trials was given and subjects were allowed to set the duration of noise administered. Heart period and skin conductance level were recorded throughout the task as set out in Chapter 3.

Subjective rating scales

The Mood Rating Scale, Anger Rating Scale, and Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory were completed at each time point (see Chapter 3). The Drinking Quesionnaire was filled in once, pre-drug, and the guess concerning alcohol once, 1 hour after the drink.

Analysis of data

A repeated measures multivariate analysis of variance was used: Each subject had four observations per variable for the ratings and three for the CRT. The between-subjects model was a two-by-two factorial design, the factors being alprazolam and alcohol. For the heart period, a within-subjects model of event and time was used and a priori contrasts were selected.

Results

Breath alcohol concentration

The breath alcohol concentration peaked at an equivalent mean of 71mg/100ml (blood) at 45 minutes after both alcohol alone and the combination. It declined to 42mg/100ml at 105 minutes and 28mg/100ml at 165 minutes post-alcohol, and 35mg/100ml and 24mg/100ml after the combination. There were no significant effects of alprazolam on the breath alcohol concentration.

Guess concerning alcohol

The placebo and alcohol groups differed in their detection of alcohol but the difference between the alprazolam and alcohol groups was not significant.

Competitive reaction time task

Level set – Trial 1. There were no significant differences on Trial 1.

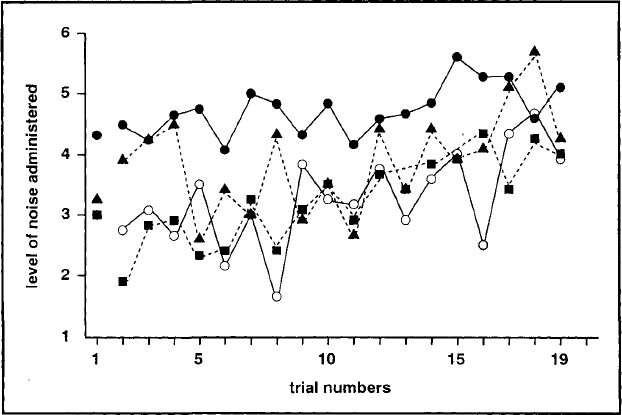

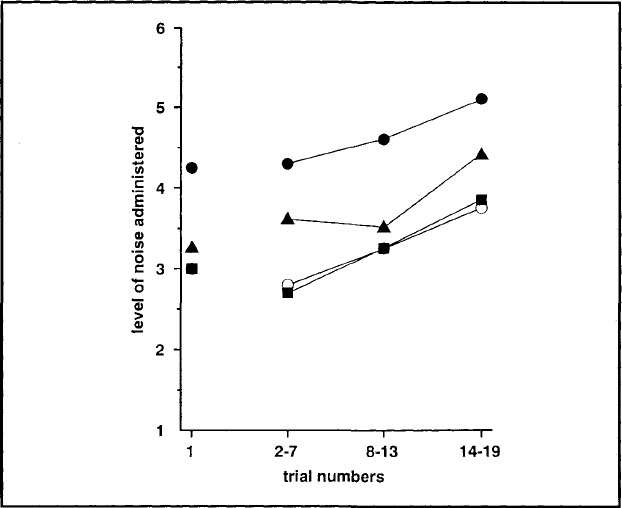

Trial blocks 1–3. The levels for each group on the 19 individual trials were plotted and there was no difference in the rate of increase between groups, i.e. the lines were parallel (see Fig. 7.1). When the trials were analysed in blocks of increasing provocation, all subjects responded to provocation by increasing the level that they set through the experiment (F2,43 = 8.77; P < 0.001 ), and this showed a linear trend. Subjects given the combination of alprazolam and alcohol set a higher level of noise for their opponent (F1,44 = 9.48; P < 0.01) throughout the task (see Fig. 7.2).

Duration of noise. Although subjects on alprazolam administered longer noises to their opponent overall, this was not significant.

Setting time. The time the subjects took to set the noise level for their opponent decreased significantly through the experiment (F2,43 = 4.31; P < 0.02) irrespective of drug administration.

FIG. 7.1. Mean levels of noise administered by subjects to their opponent on each trial of the CRT after alprazolam (![]() ), alcohol (

), alcohol (![]() ), the combination (

), the combination (![]() ), and placebo (

), and placebo (![]() ).

).

FIG. 7.2. Mean levels of noise administered by subjects to their opponent over successive blocks of trials after alprazolam (![]() ), alcohol (

), alcohol (![]() ), the combination (

), the combination (![]() ), and placebo (

), and placebo (![]() ).

).

Reaction time. There was a tendency for all subjects to become faster through the task (F2,43 = 3.14; P < 0.06). However, subjects given alcohol were generally slower (F1,44 = 8.12; P < 0.01).

Physiological measures

Skin conductance level

Alprazolam decreased baseline skin conductance level (Fl,44 = 8.76; P < 0.01). The drug also decreased the change in skin conductance level within each trial (F1,44 = 9.48; P < 0.01 ) but there were no significant changes through the experiment.

Heart period

There were no differences between groups on pre-treatment heart rate. The heart period was lengthened in all subjects 90 minutes post-administration, irrespective of group allocation.

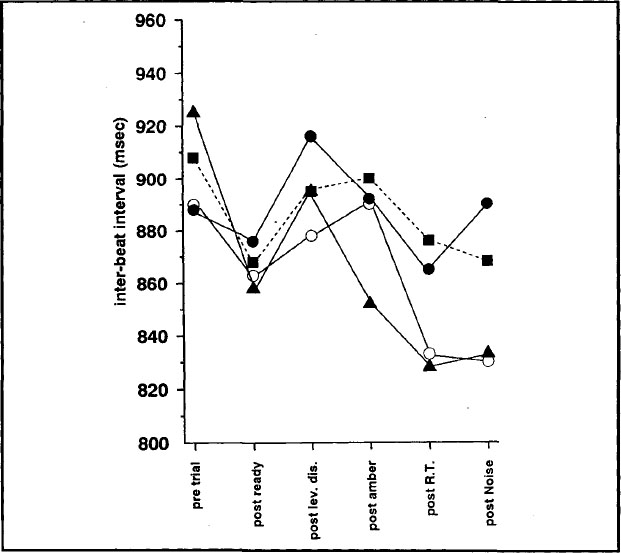

Trial 1 (nonprovocation). The heart period shortened from immediately before the start of the trial to the later points: from the mid-trial points to after the noise and from after the warning signal for RT to after RT itself, but it lengthened from after the subjects had set the noise to be delivered to their opponent to after the display of noise they themselves were to receive. Alcohol showed a significant difference on pre-trial versus the rest of the trial. Subjects who had consumed alcohol showed less change (see Fig. 7.3). When the Trial 1 heart period was adjusted for pre-drug readings, the pre-treatment heart period was found to affect the mean level (F1,43 = 8.87; P < 0.01) but not the pattern of scores.

FIG. 7.3. Mean heart period (IBI) adjusted for individual pre-treatment recordings pre-trial and after events within trial for Trial 1 of the CRT after alprazolam (![]() ), alcohol (

), alcohol (![]() ), the combination (

), the combination (![]() ), and placebo (

), and placebo (![]() ).

).

Trial blocks 1–3 (increasing provocation). Although there was a linear trend for the heart period to shorten through the experiment in all groups, this was only significant for alcohol. Alcohol shortened the heart period over trial blocks (F2,43 = 3.72; P < 0.04). There were significant differences between points measured within the trial but no change in this pattern over time. Four of the six a priori contrasts showed a significant overall effect. There was a trend for subjects who had consumed alcohol to show less change from pre-trial values to the rest of the trial (F1,44 = 3.14; P < 0.09) but this was less pronounced than on Trial 1. When the heart period was adjusted for pre-treatment readings, it was found that although the pre-treatment reading accurately predicted later readings (F1,43 = 15.26; P < 0.001), there was no change in the pattern.

Subjective rating scales

Drinking questionnaire

There were no differences between groups with respect to drinking behaviour.

Mood rating scale

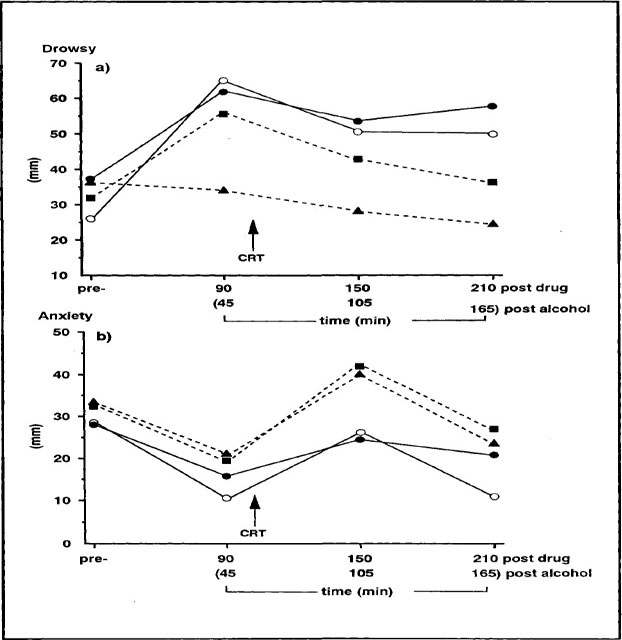

Factor 1: alertness. Subjects on all active treatments became drowsier (see Fig. 7.4a). This was significant after alprazolam (F3,42 = 7.4; P < 0.001) and there was a significant drug × alcohol interaction (F3,42 = 5.5; P < 0.01).

Factor 2: contentment. Subjects on alcohol became significantly more contented after administration and less contented after the task (F3,42 = 3.3; P < 0.05).

Factor 3: calmness. All subjects became less anxious post-administration and more anxious post-task (F3,42 = 14.0; P < 0.001) (see Fig. 7.4b).

Anger rating scale

All items on this scale showed a similar pattern. Subjects became less aggressive post-treatment and more aggressive post-task (F3,42 = 12.01; P < 0.001) with recovery at 3.5 hours post-drug (see Fig. 7.5). There was a cubic trend.

Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory.

There was no difference between treatment groups on the STAI-Trait (mean = 39). All subjects became less anxious post-administration and more anxious post-task on the STAI-State (F3,42 = 7.6; P < 0.001). There was a tendency for subjects on alprazolam to show a different pattern, in that the drug blunted the anxiogenic effect of the task (F3,42 = 2.59; P < 0.06) but anxiety rebounded later in the day.

FIG. 7.4. Mean scores on (a) Factor 1 and (b) Factor 3 of the mood rating scale pre-treatment, and at 3 testing points post-treatment after alprazolam (![]() ), alcohol (

), alcohol (![]() ), the combination (

), the combination (![]() ), and placebo (

), and placebo (![]() ).

).

FIG. 7.5. Mean scores of all subjects are shown on the mean scale score of the anger rating scale.

PATIENTS WITH PANIC DISORDER

Method

Subjects

The patients were from a treatment study of panic disorder with marked phobic avoidance described by Marks and his colleagues (1993). The 82 London patients in that study were allocated randomly to one of four treatment conditions: alprazolam and behavioural exposure, alprazolam and relaxation, placebo and exposure, placebo and relaxation.

Drugs and procedure

Only those patients who were still in the study at 8 weeks and who were prepared to come to the study site were eligible. Twenty-three patients were tested: 13 patients (5 males and 8 females with a mean age of 40.8) allocated to treatment with alprazolam and 10 patients (1 male and 9 females with a mean age of 38.5) given placebo. The data for 1 subject were lost due to equipment failure and another subject (on placebo) refused to continue after 9 trials. Complete data were therefore only available for 21 subjects (12 on alprazolam and 9 on placebo).

The study was approved by the appropriate Ethics Committee and subjects gave informed consent. Matching alprazolam (1mg) or placebo tablets were initiated under double-blind conditions at week 0 with 1 a day, rising to a maximum of 10 a day. The mean dose taken by those on alprazolam was 4.7mg/day (range 0.5–8). Patients given placebo took an average of 8.2 tablets a day (range 5–10). There were no significant differences between groups pre-treatment on a range of clinical measures, e.g. Hamilton Rating Scale of Anxiety (Hamilton, 1959), Hamilton Rating Scale of Depression (Hamilton, 1960), Beck Depression Inventory (Beck, Ward, Mendelson, Mock, & Erlbaugh, 1961), and number of major panic attacks. Subjects completed the self-ratings at entry to the study (pre-treatment) and before and after competing in the competitive reaction time task after 8 weeks of treatment.

Measures

Competitive reaction time task

See Chapter 3. Again, 19 trials were given, the task being conducted oniy once, after 8 weeks of treatment. No physiological measures were recorded.

Subjective rating scales

Self ratings

The mood rating scale, anger rating scale and Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory were completed (see Chapter 3).

Analysis of data

All groups were compared at baseline to assess between group differences on those ratings. Repeated measures MANOVA between subjects, drugs, psychological treatment, and time was used to analyse the ratings. However, as no effects were shown for psychological treatment, a further analysis was run on drugs and time. Contrast analysis was used to examine planned orthogonal contrasts pre-post-drug and pre-post-task. Analysis of variance between drugs was used to analyse trials 1–19 and the 3 blocks of trials of the CRT.

Results

Competitive reaction time task

Level set – Trial 1. There were no significant differences on Trial 1.

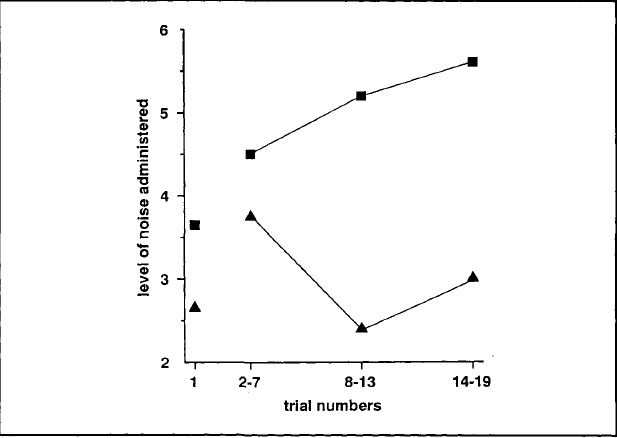

Trial blocks 1–3. There was a significant difference between groups over trials 2–19 (F1,19 = 12.57; P < 0.01) (see Fig. 7.6). When the trial blocks were examined, the groups did not differ on trials 2–7 but the alprazolam group did set significantly higher volumes of noise for their opponent on trials 8–13 (F1,19 = 14.37; P < 0.01) and trials 14–19 (F1,19 = 12.34; P < 0.01) (see Fig. 7.7).

Setting time. The alprazolam group tended to take longer to set the volume of noise for their opponent on the first trial (F1,19 = 4.16; P < 0.06) but both groups accelerated through the task (F1,19 = 9.16; P < 0.01) and there was no difference between them over trials 2–19.

FIG. 7.6. Mean levels of noise administered by subjects to their oponent on each trial of the CRT after alprazolam (![]() ) or placebo (

) or placebo (![]() ).

).

FIG. 7.7. Mean levels of noise administered by patients on alprazolam (![]() ) or placebo (

) or placebo (![]() ) to their opponent over successive blocks of trials.

) to their opponent over successive blocks of trials.

Reaction time

There was no difference between groups on reaction time on Trial 1 or on the rest of the task.

Subjective rating scales

Mood rating scale

There were no significant differences between groups pre-trial.

Factor 1: alertness. There was a significant between-times effect (pre-post-task) on the lethargic–energetic scale (F2,19 = 4.37; P < 0.03). All subjects became more energetic after the task, irrespective of drug (F1,20 = 9.15; P < 0.01). There was a significant drug × times interaction on mentally slow–quick-witted (F2,19 = 8.34; P < 0.01). Subjects on alprazolam rated themselves as more mentally slow after 8 weeks' treatment with the drug compared to those on placebo (F1,20 = 13.58; P < 0.01). There were no significant effects on the overall factor score.

Factor 2: contentment. There were significant between-times effects on contented-discontented (F1,20 = 4.16; P < 0.04) and troubled-tranquil (F2,19 = 8.68; P < 0.01). All subjects rated themselves as more contented (F1,20 = 5.35; P < 0.04) and more tranquil (F1,20 = 7.82; P < 0.02) after 8 weeks' treatment with either alprazolam or placebo. The factor score showed a tendency in the same direction (F2,19 = 2.75; P < 0.09).

Factor 3: calmness. Comparing data at entry with that at 8 weeks, there was a significant times effect on tense–relaxed (F2,19 = 8.6; P < 0.01). Subjects rated themselves as more relaxed after both alprazolam and placebo (F1,20 = 15.7; P < 0.001). The factor score also showed a significant times effect (F2,19 = 5.26; P < 0.02) in the same direction.

Anger rating scale

Two scales showed a significant difference between groups before trial. The group who were allocated to alprazolam rated themselves as more sociable (F1,20 = 5.7; P < 0.03) and more friendly (F1,20 = 6.18; P < 0.03) than the placebo group. An analysis of covariance, adjusting for pre-values, was therefore run on these two scales. There were no times effects or interactions but there was an overall drug effect on friendly-hostile (F1,19 = 17.25; P < 0.001), which was significant on the covariance analysis. There was no such effect on sociable–unsociable. Two other scales showed an overall drug effect. Subjects rated themselves as more tolerant (F1,20 = 5.01; P < 0.04) and pleased (F1,20 = 9.23; P < 0.01) on alprazolam compared to placebo. Subjects on alprazolam also tended to rate themselves as less aggressive on the mean of all 13 scales but this failed to reach significance (F1,20 = 3.77; P < 0.07). There were no differences between groups after the task.

Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory

Subjects only completed these scales at week 8, so there were no pre-treatment scores. There were no significant differences between groups after 8 weeks' treatment. The alprazolam group scored 52.5 ± 11.3 on the STAI-Trait and 43.6 ± 10.8 on the STAI-State, and the corresponding scores for the placebo group were 47.1 ± 11.7 and 46.9 ± 12.2.

DISCUSSION

None of the normal subjects were abstainers and all claimed to drink within the recommended limits. Alprazolam did not affect the breath alcohol concentrations but it did raise the amount of self-rated intoxication. It also increased ratings of sedation but these were not potentiated by the combined treatment. Anxiety was blunted by the alprazolam but hostility after the task was unaffected. Anxiety increased again 3.5 hours after the drug as its effects wore off but this may have been a harbinger of rebound. Discontent was noted only in subjects who had consumed alcohol, perhaps as the intoxication wore off.

The general pattern of effects was consistent throughout the competitive task as the level of provocation increased. All subjects decreased the time taken to choose a level of noise for their opponent and decreased the time taken to respond in an attempt to win the competition, although subjects who had consumed alcohol were generally slower. All subjects also set increased levels of noise for their opponent as the level that they themselves received increased, and the rate of increase in the four groups was similar. Subjects given either alcohol or alprazolam alone set no higher levels of noise for their opponent than subjects on placebo. Indeed, the levels set by these three groups on individual trials often overlapped, but the levels set by the group who had received both alprazolam and alcohol were higher than all other groups on 17 of the 19 trials.

The physiological effects during the task followed a similar pattern as in our other studies but the effects of the treatments differed. Increasing provocation tended to increase cardiac activity but only after alcohol. This drug is known to quicken the heart. In our study, alcohol reduced the change from pre- to within-trial periods. Subjects after alcohol therefore showed a stress-response dampening (SRD) effect, both with and without alprazolam. The effects of benzodiazepines on heart-rate are generally inconsistent (Hoehn-Saric & McLeod, 1986) but they have been shown to lower skin conductance (Albus et al., 1986). Alprazolam decreased both the SC resting level and the within-trial change and thus exerted a SRD action. However, neither alprazolam nor alcohol alone increased the level of noise set by the subjects for their opponent. Only the combination had this effect. The combination group who showed most behavioural aggression also revealed an SRD effect on both cardiac and electrodermal activity and showed decreased anxiety. It may be that a treatment that decreases physiological and subjective responses to stress facilitates an aggressive response to provocation. It has been suggested that alcohol-induced anxiety reduction is accompanied by a decrease in aggressive restraints (Horton, 1943).

A moderate dose of alcohol was used to represent what a person being prescribed a benzodiazepine might cautiously consume at a social event, but in fact subjects consuming alcohol alone did not respond more aggressively than those on placebo. Comparing the results with our previous experiments, the alcohol group actually responded more aggressively than a group previously administered 0.25g/kg of alcohol (Chapter 5) but the placebo group was more aggressive. In previous experiments, the placebo groups have been more comparable, averaging a noise level of less than 3 over 3 trial blocks, but in this experiment they started off at over 3 and increased to over 4. It is not known why the current placebo group should be more aggressive, but nevertheless the combination increased aggression more than would have been predicted by the summation of the two individual treatments. This result confirms that the behavioural aggression reported after the combination of alcohol and alprazolam (Terrell, 1988) can be modelled in healthy volunteers in the laboratory.

The second alprazolam study accords with previous clinical reports of increased hostility and aggression after taking this drug. Although patients given alprazolam were more aggressive behaviourally throughout the task, this was not significant on the pre-provocation trial, i.e. before they knew what level of noise their opponent would set for them, or when they received only low volumes of noise if they lost the competition. In fact, the two groups increased in parallel at this point. However, when the noise intensified, the patients taking alprazolam continued to increase the level they set, whereas those on placebo decreased the level. The patients taking alprazolam were thus much more likely to respond to provocation. This was similar to the pattern of effects after a single 2mg dose of lorazepam (Chapter 6). Unfortunately a gender bias occurred in the random allocation of subjects to alprazolam or placebo in this study. There was only one male in the placebo group but five in the alprazolam group. In previous studies on benzodiazepines and aggression no sex differences have been found (see Chapter 6; Taylor & Chermack, 1993). However, we decided to examine the data more closely for two reasons. First, healthy male subjects behave more aggressively in response to provocation than female subjects after alcohol (Chapter 5) and second, as more women present with anxiety disorders, they are also more likely to be prescribed drugs like alprazolam. We analysed the data for the 16 females separately, but the results closely resembled the original analysis. Again, no difference was found on the first seven trials but the patients on alprazolam set significantly higher levels of noise for their opponent on both later blocks (P < 0.05). This is based on a rather small number of subjects but shows that the full result was not an artefact due to gender.

Interestingly, the behavioural aggression shown in this study was not accompanied by subjective ratings of increased anger or hostility. In contrast, the group taking alprazolam tended to note less aggression, rating themselves as more tolerant, friendly, and pleased. This kind of dissociation between behaviour and feelings has been noted before after consuming alcohol (Chapter 5) and is likely to reflect a lack of insight. Most case reports detailing extreme aggressive behaviour after the consumption of benzodiazepines describe accompanying anger. However, studies that report specifically on extreme rage or physical assaults tend to underestimate the number of patients who may display a general increase in aggressiveness or irritability without recognising any emotional changes or link to medication (Dietch & Jennings, 1988). Such patients may maintain that the drug calms them down. The present study used a parallel groups design. Recently case reports have accrued of anger attacks as a component of untreated panic disorder (Fava et al., 1990) and of major depressive disorder (Fava et al., 1993). Therefore, the patients allocated to alprazolam might be more likely to display aggression, irrespective of drug treatment. This seems unlikely as the patients were matched pre-treatment on a number of clinical indices. Dosage is a crucial element in our findings. The mean dose of 4.7mg was the same as that used by Gardner and Cowdry (1985). Early reports of rage attacks were often related to high doses, and problems with triazolam have been blamed on exceeding the clinically recommended dose (Drug and Therapeutics Bulletin, 1991). Plasma concentrations of alprazolam have been found to relate not only to treatment response but also to the emergence of adverse reactions (Lesser et al., 1992) and it is possible that increased hostility and aggression occur above a certain threshold. However, Lesser et al. (1992) found considerable between-patient variability, indicating that some individuals may be more likely to display such behaviour at doses within the recommended therapeutic range. Increasing the dose may therefore just augment the number of people susceptible to such effects.

SUMMARY

Forty-eight moderate social drinkers were assigned to one of four treatments: alprazolam (1mg) and alcohol (0.5g/kg); alprazolam (1mg) and placebo drink; placebo capsule and alcohol (0.5g/kg); and placebo capsule and placebo drink. Breath alcohol concentrations and ratings of mood and intoxication were completed at 90, 150 and 210 minutes post-drug (45, 105, and 165 minutes post-alcohol). Subjects competed in a competitive reaction time task at 105 minutes post-drug (60 minutes post-alcohol) during which psychophysiological measures were simultaneously monitored. Active treatments increased sedation and intoxication and the task increased feelings of hostility and anxiety in all subjects. Aggressive responding increased in all groups in response to provocation, but some stress response dampening was shown after both alcohol and alprazolam on the psychophysiological measures and after alprazolam on subjective ratings of anxiety. The combination of alprazolam and alcohol increased behavioral aggression more than would have been predicted from the sum of the single effects, confirming clinical reports of behavioural dyscontrol.

Twenty-three patients with a diagnosis of panic disorder with agoraphobia were randomly assigned to 8 weeks' treatment with alprazolam or placebo. They filled in self-ratings before and after treatment and competed on a competitive reaction time task, designed to measure behavioural aggression, after 8 weeks' treatment. Patients taking both alprazolam and placebo rated decreased anxiety after 8 weeks' treatment but those on alprazolam also tended to report less hostility On the behavioural task patients on alprazolam behaved more aggressively in response to provocation. This is the first study to confirm clinical reports of benzodiazepine-induced dyscontrol on an objective laboratory measure.