CHAPTER 36

Why IT Matters: Project Management for Information Technology

Information technology plays an ever-increasing role in the delivery of the services that we rely on in our everyday lives. Information technology surrounds us, from the technology with which we manage our households, to the technology that is used in our schools and workplaces, to the technology we use to interact with one another. Information technology is no longer confined to the business community. Management of the projects by which that technology is delivered to us is of ever increasing importance.

VISIBILITY OF IT PROJECT FAILURES

It should come as no surprise that failures of information technology (IT) projects often have a negative impact on the business organization sponsoring the project. There have been numerous reported cases where the failure of IT to deliver much needed capabilities impacted a company’s financial standing, market shares, or even worse. A search on the Internet using the term “IT Project Failure” brings up numerous articles and blog-sites identifying the costs of IT project failures and the impact those failures had on the business. Some of the projects cited in a Computerworld, September 2002 article include ERP implementations and large-scale custom development efforts.1 In 2003, CIO magazine discussed some of the challenges facing the IRS Modernization Project, an $8 billion project involving infrastructure upgrades and modifications or replacement of over 100 separate applications, and the issues confronted in AT&T’s Wireless recent upgrade.2 A more recent failure cited in business news relates to the contribution a failed IT project had on the failure of a UK bank. While the various lessons cited in these references were certainly of interest, what is even more important a lesson to learn is the potential impact these failures had on the corporations, their markets, their customers and their employees. IT matters in a technology-enabled world, and IT project management matters as well.

IT PROJECT MANAGEMENT MATTERS

As information technology becomes more pervasive in our lives (programmable dishwashers, cell phones, GPS systems, home networks, medical diagnostic and drug-delivery techniques, etc.), the need to treat the development of the products and software embedded in them as true engineering activities has increased. These products could have as much safety implications as building a bridge or constructing a house. That level of engineering requires formal project management discipline.

In addition, many corporations are feeling pressure from participation in a global economy. The need to develop products and services faster and more economically translates into a requirement for a more disciplined approach to managing their development without sacrificing time to market considerations.

What does all this mean?

For companies, it means recognizing formal project management as a discipline within their information technology departments, a discipline as crucial as database management or network security management. For the project manager, it means recognizing the need to acquire and apply additional knowledge and skills, in a more formal and disciplined manner than traditionally. And, for the project team (which includes business participants), it means understanding—and appreciating—the contributions formal project management makes to the overall project success.

FORMAL IT PROJECT MANAGEMENT

A project, by definition, has a specific beginning date and a specific end date. Thus, operations and maintenance of an IT system is not a project, although there might be maintenance projects undertaken in the fulfillment of that objective. Establishing user access and monitoring network security is also not a project, although introduction of a new security capability would be a project. It is important to realize that formal IT project management does not mean mounds and mounds of more paper, nor does it mean lots of additional project staff. What it means is recognizing there are some formal project management roles to be fulfilled and formal project management disciplines to be applied within an IT project.

FORMAL IT PROJECT MANAGEMENT ROLES

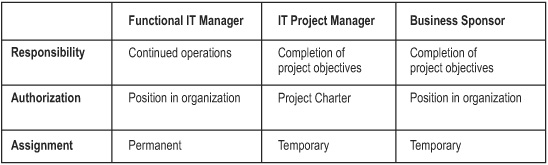

Formal IT project management begins with a clear understanding of the roles and responsibilities of the IT project manager, versus the roles and responsibilities of the project’s business sponsor, versus the roles and responsibilities of the functional IT manager. These roles and responsibilities are briefly summarized in Table 36-1.

Let’s start with an exploration of the IT Functional Manager role. Many IT organizations are structured around business areas supported, which often translates into oversight of specific applications or product lines or specific operational activity. Typical titles used for the individuals who manage these operational activities include Application Manager, Product Line Manager, and Data Center Manager. Their responsibilities often include an operational or maintenance type of function, the “Lights On” role within IT. While their daily activities are quite varied, their overall contribution to the business is the same: keep operations running, ensure the various IT capabilities are available to the business units relying on them. IT Functional Managers are often key stakeholders in IT projects, most often as providers of knowledgeable, experienced project staff, as quality control participants and as the recipients of the project’s deliverables.

TABLE 36-1. TYPICAL ROLES AND RESPONSIBILITIES

Compare these responsibilities with those of the IT project manager. An IT project manager’s responsibilities are established when the project is initially conceived and are concluded when the project’s deliverables are completed, when the end state is achieved. The typical responsibilities associated with the project manager role include identifying the specific work to be performed, determining and obtaining the corporate resources (budget, people, facilities) required to achieve the project’s objectives, and then managing those resources as they are used to perform the project’s identified work. It is the project manager’s responsibility to ensure that any changes in the definition of the project’s end state are reflected in the project’s governing documents, that the Business Sponsor agrees to impacts to budgets or schedules. The project manager is also responsible for the communication of the project status to the Business Sponsor and other project stakeholders, which often include the functional IT managers.

There are organizations where an IT Functional Manager will assume the role of IT project manager on occasion, managing the enhancement of an existing application or the introduction of a new capability into the IT portfolio. It is important for the person fulfilling these two roles to be aware of the distinctions and to not allow operational considerations, such as staff availability, impede success of the project. As the project manager, the IT Functional Manager needs to ensure that the staff time required to work on the project is made available and that operations “hot items” do not prevent project progress.

The Business Sponsor role is akin to that of the homeowner in a construction project. The Sponsor is the ultimate owner of the project, representing the business users for whom the IT product or service is being provided. The Business Sponsor is responsible for making decisions regarding scope, schedule, and budget trade-offs, after listening to advice and recommendations from the experienced IT project manager.

FORMAL IT PROJECT MANAGEMENT METHODOLOGY

Before discussing methodologies and application of them within IT projects, it is necessary to define some common terms often used interchangeably. A methodology is defined as a body of methods and rules followed in a science or discipline. Christensen and Thayer cite IEEE Standard 12207.0-1996 as defining a life cycle model as “a framework containing the processes, activities, and tasks involved in the development, operation, and maintenance of a software product, spanning the life of the system from the definition of its requirements to the termination of its use.”3 A project life cycle is a collection of generally sequential project phases, the names and number of which are determined by the control needs of the organization or organizations involved in the project. Finally, a body of knowledge can be defined as the sum of knowledge within a profession. Bodies of knowledge are often used as best-practice standards.

There are a number of bodies of knowledge with which the IT project manager should be familiar. Of particular interest is the project management body of knowledge, as described in the Project Management Institute’s standards document.4 The PMBOK® Guide identifies the primary practices involved in managing any project. Now in its fourth edition, the Guide is a mature and evolving representation of the project management body of knowledge.

Project managers working within a corporation with IT projects being executed outside North America might also be practitioners of the practices called out in PRINCE2 (Projects in a Controlled Environment), a standard approach to project management developed in the late 1980s by the United Kingdom’s government. PRINCE2 divides projects into stages, with reviews and go/no go decisions specifically called out at the end of each stage. It also places an emphasis on the product via the use of a product breakdown structure.

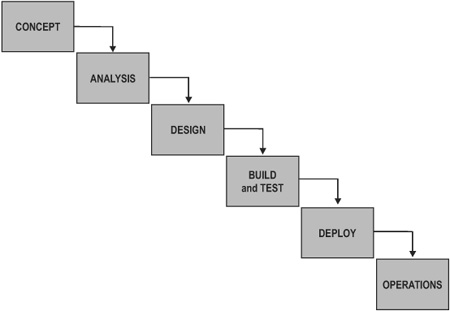

FIGURE 36-1. TYPICAL WATERFALL LIFE CYCLE METHODOLOGY

Another guide to a body of knowledge is IEEE’s Guide to the Software Engineering Body of Knowledge (SWEBOK).5 At this writing, still in the early stages of industry awareness, the SWEBOK Guide provides knowledge and insight into software engineering practices such as requirements definition and management, software quality control, and software design.

One other often cited collection of best practices with which the IT project manager should have some familiarity is the Software Engineering Institute’s Capability Maturity Model (Integrated), commonly called CMMI.6 The CMMI identifies best practices an IT organization (which could be defined as an IT project organization!) should deploy in support of successful systems development. Grouped around nine key practice areas, the CMMI associates objectives and goals with specific activities.

Many organizations have well-established systems development methodologies (SDLCs), addressing the activities required to conduct the technical work of the project. Figure 36-1 depicts a typical Waterfall Life Cycle Model. Note that the work to be performed is discussed in system development terms.

Whatever methodology is followed, a formal IT project management methodology would describe the activities and steps associated with each of five project phases: Initiate, Plan, Execute, Control, and Close. For instance, the methodology would prescribe how to develop the project charter, the content of the project charter, and who should participate in its development, review, and signoff. The methodology would contain a sample of a project charter, as well as a template for the project manager to use. Figure 36-2 depicts the processes one would typically find in a project management methodology.

FIGURE 36-2. TYPICAL PROJECT MANAGEMENT METHODOLOGY

Much has been written recently regarding agile IT projects, including agile project management as well as agile software development methods. The IT Project Manager should consider agile methods as another set of methods from which he can select when developing his project’s particular life cycle model. Agile techniques are not risk-free and the project manager needs to carefully consider if the risks associated with agility are justified for the project being undertaken.

The Project Manager also needs to consider his personal strengths when considering an agile project life cycle. The application of agile methods requires more leadership and less actual management. The contributions of the Project Manager in an agile project need to be those of a team leader, or facilitator. With an increased emphasis on the team (which includes the project’s customers) making decisions based on the information provided by the team, the Project Manager’s contributions are more focused on “roadblock removal,” looking ahead in the project schedule and anticipating and addressing those actions that might impede the project team’s progress.7

BEST PRACTICES

As the formal practice of project management within information technology organizations has matured over the last decade, several practices have become generally recognized as “best practices” that, when applied, can assist project teams in meeting deliverable expectations.

Establish a Formal Project Life Cycle Model

Within formal IT Project Management, one of the initial activities the IT project manager undertakes is developing his project’s specific life cycle model, drawing from both a project management methodology and a systems development methodology.

It is often observed that formal methodologies impose additional work on project teams. A well-developed methodology does not impose additional work unnecessarily. Rather, the methodology provides the IT project manager and the project team a guide by which they can conduct project activities. The project team should use the Project Management methodology and a System Development methodology as resources from which they can develop their project’s life cycle model, applying the concepts of “tailoring” and “just enough process” to ensure the project’s life cycle model meets their needs.

Let me explain further. When the IT project manager surveys the PM Methodology and the SDLC to be applied within his project life cycle model, he should consider the risk profile of the project. For instance, if the project manager is working with a close-knit, co-located project team, he might find formal weekly status reporting to the project team is not necessary, but if the project team is working together for the first time or is geographically dispersed, it might be advantageous to have a formal time each week for the team to interact with each other. Formal change control processes are indicated if the work is being performed under a fixed price contract with a business unit or external customer. The risk profile of the project will indicate how much formality is needed in the project and which project life cycle should be followed. If the project being undertaken is risky, the project manager should consider an iterative development approach, with formal scope statements and frequent schedule/budget updates, and a more rigorous approach to identifying and managing risks. A project that is viewed less risky, perhaps a repetitive maintenance project to an existing application, might not require as much rigor. A project with intense time to market considerations might warrant application of some of the agile methods.

When the project team has developed their project’s life cycle model, identifying the approach and processes they will use to manage the project’s activities, it is recommended that the Business Sponsor and any internal oversight body, such as a Quality Assurance organization, review and approve the tailoring. The project manager should be able to defend the decisions made as to the degree of formal methodology compliance he will follow on the project.

Table 36-1 shows a possible partial project life cycle model developed using a waterfall systems development methodology, in addition to a project management methodology, and expressed in terms of an activity list.

Leveraging Project Sponsors and Business Community

It is important to realize that most projects are not IT projects, but business projects being completed by the IT organization. The resourceful IT project manager will view his business sponsor as an equal partner in the project. Even those projects that are mostly technology in nature (for instance, an operating system upgrade) have a business sponsor, perhaps one of the IT Functional Managers.

Involving the Business Sponsor and user representatives in the planning of a project might seem risky and politically unsafe to the IT project manager. However, the more participatory and open the planning activities are, the fewer surprises there will be for the Business Sponsor when the project schedule or budget is presented. It has been my personal experience that often times the Business Sponsor does not appreciate the details associated with developing software or implementing a new package. Involving that Sponsor in the development of the project’s work breakdown structure, or in the Risk Identification workshop, or in the development of the project’s communications plan, provides the IT project manager with an opportunity to educate the Sponsor and to obtain the Sponsor’s buy-in on the project management deliverables. The Sponsor will understand why these additional activities are actually to his benefit.

Representatives from the user community should also be viewed as resources to be assigned to the project. They are the experts when it comes to defining the project’s business requirements. They are also the experts as to how those business requirements should be validated as implemented. User representatives should be assigned as project team resources to participate in the definition and creation of test cases, and then in the execution of those test cases. Because they defined the requirements, they will best know when the requirement is implemented correctly.

When status reports are to be delivered, or important project decisions are to be made, the Business Sponsor should be actively involved. In fact, one could argue the Sponsor is the only member of the project team empowered to make decisions regarding scope, budget, and schedule. The project manager ’s role is to make sure the Sponsor makes an informed decision.

Internal Contracts

When managing internal IT projects for one of my former employers, I often negotiated contracts with my internal customers. What did this mean? It meant the project charter and associated project plan (including schedule, budget, deliverable definitions, and responsibility matrix) was a document that we both agreed to and signed. This then became a contract upon which our performances would be evaluated. I committed to delivering on schedule and within the prescribed budget; the customer agreed to actively participate in requirements management and testing activities, and to managing scope. Any change to the content of the project plan was treated as a contractual change, resulting in a new contract.

Waterfall Development Methodology |

|

|

|

INITIATING PHASE |

CONCEPT DEVELOPMENT |

Perform Project Management |

Feasibility Assessment |

Project Administration |

Review and Document known requirements |

Change Control |

Assess system architectures ability to support needs |

Team Meetings |

Identify probable risk areas |

Quality Assurance |

|

Cost Control |

Scope Definition |

Schedule Control |

Document In and Out of scope conditions |

Risk Control |

Create first level functional prioritization matrix |

Status Reporting |

Document critical success factors |

Establish System Request |

Scope Review |

Enter System Request |

Develop Presentation |

Develop Project Charter |

Schedule Review |

Develop Goals and Objectives |

Present Findings |

Develop Business Case |

Business Case Development |

Develop Cost Benefit |

Apply ROM estimates to functional priorities |

Secure Sign-off |

Determine risk weighting factors |

Establish Project Planning Schedule |

Develop probable cost model |

Develop Project Planning Schedule |

|

Select Project Team |

|

Perform skills analysis |

|

Select team members |

|

Communicate Project Charter |

|

Goals and Objectives |

|

Business Case |

|

Obtain Project Approval |

|

Approval |

|

|

|

PLANNING PHASE |

REQUIREMENTS ANALYSIS |

|

|

Establish Project Plan |

Hold Team Kickoff Session |

Develop Project Plan |

|

Develop Scope Statement |

Requirements Gathering |

Develop Team Assignments |

Gather documentation |

Develop Communication Plan |

Perform necessary interviews |

Develop Change Control Plan |

Establish requirements prioritization matrix |

Prepare Project Plan Document |

|

|

Requirements sessions |

|

Review Critical Success Factors |

|

Review Risk Factors |

|

Validate Requirements Matrix |

Establish Project Schedule |

Prioritize Requirements |

Develop WBS |

Validate Cost estimates per functionality |

Develop Estimates |

Develop Use Case Scenarios |

Develop Critical Path |

Develop performance requirements |

Produce Project Schedule |

|

Resource Schedule by Role/Skill set |

Package Evaluation |

Resource Schedule by Name |

Perform industry search |

|

Validate package functionality against requirements |

|

|

Schedule & Resource Validation |

Perform Gap Analysis & costing |

Validate Resources (per increment if necessary) |

Develop trade-off matrix |

Validate Schedule (per increment if necessary) |

Vendor recommendation |

Obtain Vendor Information |

Visual Specification Development |

Develop RFI |

Develop story board |

Issue RFI |

Design screen mock-ups |

Acquire Vendor(s) |

Review content against requirements |

Develop RFP |

Develop functional flow |

Develop Contract and SOW |

Finalize graphical presentation |

Negotiation |

Perform team review and validation |

|

|

|

Requirements Review |

|

Develop Presentation |

|

Schedule Review |

|

Present Findings |

|

Make team recommendation |

TABLE 36-1. SAMPLE PARTIAL PROJECT LIFE CYCLE MODEL

IT Project Management Office

The use of an IT Project Management Office has become an industry best practice.8 The IT Project Management Office is often implemented in one of two models: A “Center of Excellence” or a “Shared Services.”

In a “Center of Excellence” model, the IT Project Management Office serves as the keeper of the methodologies and all related activities, including methodology training and mentoring, as the quality assurance mechanism, and as the ultimate source on all matters related to IT Project Management best practices. Note that in this model, the IT PMO also oversees all IT methodologies and standards, not just those pertaining to project management. The PMO staff would oversee the systems development methodologies, the configuration management and quality control standards and the use of any supporting tools such as scheduling and estimating tools. In this model, project managers do not report to the PMO.

In a “Shared Services” model, the IT PMO provides the above activities in addition to being the functional provider of project managers to projects within the IT organization.

A third function often played by an IT PMO is that of “project portfolio manager.” Staff within the IT PMO obtains project status data from project managers and administers periodic project reviews. They facilitate reviews of the IT Project Portfolio, assisting in determining which projects require additional management attention and which projects should be initiated or cancelled.

Power of Internet Collaboration

One of the side benefits from the emergence of technology into our everyday lives is the availability of technology as a tool for IT projects to leverage. The power of the Internet and online collaboration tools and web-based repositories means that project teams (including user representatives) no longer need to sit in the same conference room to review a presentation. They can participate in a virtual project room, where they all have access to the project documentation being reviewed. Certain technologies support real-time editing of the documents. Other products support team brainstorming and decision-making. This ability to function as a team while physically dispersed means an IT project manager potentially has a greater resource pool upon which to draw.

CHALLENGES FOR THE IT PROJECT MANAGER

What challenges exist today and in the near future for the IT project manager?

Staying Abreast with Technology

One of the most obvious challenges is the ability to stay abreast with the technology. The onslaught of wireless and gaming technologies and the integration of these into business solutions, in addition to the legacy mainframe and client server technologies, is changing the way we think of information technology. The effective use of information technology is indeed a strategic market differentiator for many businesses. A prime example is the rollout of RFID within the Wal-Mart business community.9

The management of the projects associated with this particular endeavor can mean tremendous profits to some companies. So while the affected project managers do not need to personally be RFID experts, they do need to be sure they are comfortable with the plans and schedules they are operating under, and that any risks of schedule slippage are communicated in a timely manner to their business sponsors.

Increased Emphasis on Security and Privacy

Another current technology issue is the increased emphasis on security and information privacy. In particular industries, notably healthcare and financial services, this issue is of real concern to the IT project manager. There are legal requirements that limit how one uses “live data” to create “test data” and how much data can be displayed to a particular user. The IT project manager needs to be aware of these requirements in order to ensure that the product he delivers to his user community is in compliance, just as the general contractor in a construction project needs to ensure compliance to building and safety codes.

Should the IT project manager be involved in a project introducing wireless technologies into an organization, he needs to be sure that the activities associated with protecting the data being transmitted over that technology have been considered and are suitably addressed.

Outsourcing

One other trend that continues to haunt the IT project manager is the increasing pressure to expedite project delivery through leverage of third party service providers—either in the form of software to be integrated into a solution or in the form of contract labor. This business trend can result in the IT project manager being the manager of multiple services contracts, with associated service level agreements, where the actual information technology development work is performed by a third-party. This means that an IT project manager needs to be up to speed on reading and interpreting contracts and enforcing their terms, as opposed to managing a project team. Many IT project managers will lack the business law training required to feel totally comfortable in this role. If you are a “technology-focused” project manager, with a degree in Computer Sciences, enroll in a Contractual Law course to obtain a basic understanding of contract management.

OUTLOOK FOR THE FUTURE

By now, you will have an appreciation of the pervasiveness of information technology and the need for increased discipline in the management of those technology projects. The future will indeed include further personal accountability for the IT project manager. Just as society holds the General Contractor accountable for safety and code compliance in his construction projects, so will society hold the IT project manager accountable for safety and information privacy. There will be an increased emphasis on licensure, oversight boards, and specialized certifications in order to manage certain types of projects.

That said, the field of IT Project Management will indeed become a profession, through the efforts of organizations such as Project Management Institute (PMI), Association for Computing Machines (ACM), Software Engineering Institute (SEI) at Carnegie-Mellon University, and IEEE’s Computer Society, to name just a few. The forward-thinking IT project manager will stay abreast with the developments within these organizations in order to be better positioned as a “professional IT project manager.”

REFERENCES

1 The Best and the Worst, Computerworld, September 30, 2003.

2 Elana Veron, For the IRS, “There is No EZ Fix,” CIO, April 1, 2004; Christopher Koch, “Five Lessons from AT&T’s Wireless Project Failure,” CIO, April 15, 2004.

3 The Project Manager’s Guide to Software Engineering’s Best Practices, Mark J. Christensen and Richard H. Thayer, IEEE Computer Society, Los Alamitos, CA, 2001

4 Project Management Institute, A Guide to Project Management Body of Knowledge, Fourth Edition, PMI: Newtown Square, PA: 2008.

5 IEEE Computer Society, Guide to the Software Engineering Body of Knowledge, IEEE Computer Society, Los Alamitos, CA, 2001. 10. Further information on the SWEBOK and the associated certification program can be found at www.swebok.org.

6 Further information on the CMMI model can be found at www.sei.cmu.edu/cmmi/cmmi.html.

7 Karen R. J. White, Agile Project Management: A Mandate for the 21st Century, Center for Business Practices, 2008.

8 Richard Pastore and Lorraine Cosgrove Ware, The Best Best Practices, CIO, May 1, 2004.

9 Carol Sliwa and Bob Brewin, RFID Tests Wal-Mart Suppliers, Computerworld, April 5, 2004.