CHAPTER 3

Project Management Process Groups

Project Management Knowledge in Action

One often hears the project management profession’s standard, A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK® Guide), described as consisting of nine knowledge areas. What is left out of this description is the equally important segment of the standard that describes the processes used by the project manager to apply that knowledge appropriately. These processes can be effectively arranged in logical groups for ease of consistent application. These process groups—Initiating, Planning, Executing, Monitoring and Controlling, and Closing—describe how a project manager integrates activities across the various knowledge areas as a project moves through its life cycle. So, while the knowledge areas of the standard describe what a project manager needs to know, the process groups describe what project managers must do—and in roughly what order.1

Historically, the definition of the processes that make up projects and project management was a tremendous milestone in the development of project management as a profession. Understanding the processes as described in the PMBOK® Guide is a first step in mastering project management. However, as the practice of this profession matures, our understanding of its processes also matures and evolves. This is reflected in the additions and changes made to successive editions of the standard over the years.

In the PMBOK® Guide, 2000 Edition, processes were divided into two classifications that were essentially only virtual groupings of the project management knowledge areas; these were classified as the Core and Facilitating Processes.2 This was an attempt to provide an emphasis to guide the project manager through the application of the knowledge areas to implement the appropriate ones on his/her project. However, a clear differentiation between the Core and Facilitating processes was not provided. The project manager also needed information about when and how to use the processes in those classifications. Subsequently, many inexperienced project managers used the differentiation to focus on the Core processes, while only addressing the Facilitating processes if time permitted. After all, they reasoned, they are “merely” facilitating processes, not core processes.

Therefore a key change was made in 2004 in the PMBOK® Guide, Third Edition. The artificial focus classifications of Core and Facilitating processes were removed to provide an equal emphasis on all of the processes within the knowledge areas in the PMBOK® Guide.3 To understand this, it is important to know that a process is a set of activities performed to achieve defined objectives. All processes are all equally important for every project; there are no unimportant project management processes. A project manager uses knowledge and skills to evaluate every project management process and to tailor each one as needed for each project. This tailoring is required because there has never been a “one-size-fits-all” project management approach. Every company and organization faces different constraints and requirements on every project. Therefore, tailoring must be performed to ensure that the competing demands of scope, time and cost, and quality are addressed to fulfill those demands. These demands may require a stronger focus on quality and time, while attempting to minimize cost—an interesting project management challenge.

The odds of a project being successful are much higher if a defined approach is used when planning and executing a project. The project manager will have an approach defined for the project’s specific constraints after the tailoring effort is completed. This approach must cover all processes needed to adapt capture and analyze customer interests, plan and manage any technology evolution, define product specifications, produce a plan, and manage all the activities planned to develop the required product.

PROJECT MANAGEMENT PROCESS GROUPS

The Project Management Process Groups are a logical way to categorize and implement the knowledge areas. The PMBOK® Guide, Fourth Edition, requires every process group for every project. However, the tailoring and rigor applied to implementing each process group are based on the complexity and risk for the specific project.3 The project manager uses the Process Groups to address the interactions and required trade offs among specified project requirements to achieve the project’s final product objective. These Process Groups may appear to be defined as a strict linear model. However, a skilled project manager knows that project artifacts, like the business cases, preliminary plans, or scope statements, are rarely final in their first drafts. Therefore, in most projects, the project manager must iterate through the various processes as many times as needed to define the requirements then to refine the project management plan which is used to produce a product to meet the requirements.

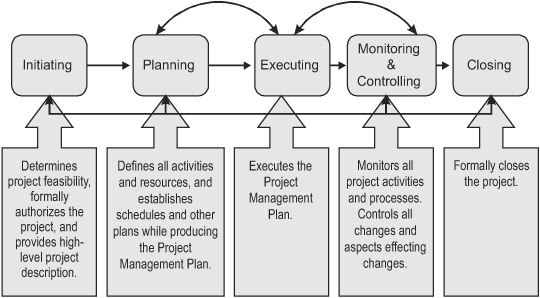

The project manager will iteratively apply the processes within the process groups to every project as shown in Figure 3-1. It illustrates how the output of one process group provides one or more inputs for another process groups, or even how an output may be the key deliverable for the overall project.

FIGURE 3-1. PROJECT MANAGEMENT PROCESS GROUPS’ INTERACTIONS

These Process Groups are tightly coupled since they are linked by their inputs and outputs. This coupling makes it clear the project manager must ensure that each process is aligned with the other processes for a successful project. The Process Groups and their interactions are very specific to the application of the project management knowledge areas when managing a project. A project manager skilled in applying these knowledge areas never confuses the process group interactions with the phases in a product life cycle and is able to apply the interactions in the Process Groups to drive a project life cycle to its successful completion.

At one time or another, every project manager has been involved with a project that was started without appropriate analysis and preparation then ended up costing the company a significant amount over its budget. A case in point, a high-level manager at a customer site may mention an idea to someone in a development company and that idea hits a spark. They take the idea and launch into production. When the finished product is completed, there is surprise all around. The customer does not remember any request for this product and the production company cannot sell it to anyone else. Now what issues are apparent in this scenario?

• It is not clear whether the idea expressed a valid need.

• It is not clear whether there were real or imagined requirements.

• It is not clear if there was an analysis of a return on investment.

• It is not clear whether there was a delivery date.

• It is not clear whether needed resources were pulled from other projects or if there was an impact to other schedules.

• It is not clear that a market need was established prior to development.

The Initiating Process Group is required to answer these types of questions and to formally begin project activities.4 The project manager uses the initiating processes to start the project by gather and analyzing customer interests and then addressing any issues or risks and project specifics. The project manager must iterate through the needed initiation activities to identify the service or product requiring the project’s effort. The organization must take a critical look at the feasibility and technical capability of creating the product or service as the requirements become more refined. After the appropriate analysis, a Project Charter is produced that addresses at a minimum the following information:

• It provides formal authorization for the project.

• It provides a high-level description of the product or service that will be created.

• It defines the initial project requirements, constraints, and assumptions. The constraints and assumptions typically provide the initial set of negotiating points for the project plan.

• It designates the project manager and defines the project manager’s authority level.

• It specifies any hard delivery dates if those dates required by the contract.

• It provides an initial view of stakeholder expectations.

• It must also provide an indication of the project budget.

The project manager works with the customer to capture the customer’s interests and analyze them to develop the initial scope statement. Typically content detail varies depending on the product’s complexity and/or the application area. This document provides a very high-level project definition and should define project the boundaries and project success criteria. It should also address project characteristics, constraints, and assumptions.

The documents developed during this series of processes are provided as input to the planning effort. Unfortunately, some project managers learn a hard lesson about the importance of a defined project plan. A plan is not just a way to focus on tasks; it is a tool to focus efforts and accomplish what is required by the due date. The plan is used to keep the project on track—a project manager knows where the project is in relation to the plan and can also determine the next steps especially is discovery is needed. A lesson learned is attempting to run a project without a plan is like trying to travel to a destination via an unknown route using a map, while having no current location and no indication of a direction to take. Therefore, a map is a useless tool in this instance.

Additional confusion is introduced when some project managers confuse the Gantt chart—which is defined by commercial tools as a “project plan”—with an actual project management plan as defined in the PMBOK® Guide, Fourth Edition.5 A real project management plan provides needed information about:

• Which knowledge area processes are needed and how each was tailored for this particular project, especially how rigorously each of those processes will be implemented on the project.

• How the project team will be built from the resources across the organization or will be brought in through contract, hiring of full-time employees, or outsourcing.

• Which quality standards will be applied to the project, and the degree of quality control that will be needed for the project to be successful.

• How risks will be identified and mitigated.

• Which method will be used for communicating with all of the stakeholders to facilitate the timing of their participation to facilitate addressing open issues and pending decisions.

• Which configuration management requirements will be implemented and how they will be performed on this project.

• A list of schedule activities, including major deliverables and their associated milestone dates.

• The budget for the project based on the projected costs.

• How the project management plan will be executed to accomplish the project objectives, including the required project phases, any reviews, and the documented results from those phases or reviews.

Planning activities are the central activities the project manager continues throughout the project. They are iteratively revisited at multiple points within the project. Every aspect of the project is impacted by the project management plan or conversely impacts the plan. It provides input to the executing processes, to the monitoring and controlling processes, and to the closing processes. If a problem occurs, the planning activities can even provide input back to the initiating activities, which can cause a project to be rescoped and have a new delivery date authorized. The project manager integrates and iterates the executing processes until the work planned in the project management plan has produced the required deliverables. The project manager uses the project management plan and manages the project resources to actually perform the work planned in the project management plan to produce the project deliverables. During execution, the project manager will also develop and manage the project team and facilitate quality assurance. The project manager also ensures that approved change requests are implemented by the project team. This effort ensures that the product and project artifacts are modified per the approved changes. The project manager communicates status information so the stakeholders will know the project status, started or finished activities, or the late activities. Key outputs from executing the project management plan are the deliverables for the next phase and even the final deliverables to the customer.

The project manager uses monitoring and controlling processes to observe all aspects of the project. These processes help the project manager proactively know whether or not there are potential problems so corrective action can be started before a crisis results. Monitoring project execution is important, because a majority of the project’s resources are expended during this phase. Monitoring includes collecting data, assessing the data, measuring performance, and assessing measurements. This information is used to show trends and is communicated to show performance against the project management plan.

Configuration management is an essential aspect of establishing project control. Therefore, configuration management is required across the entire organization, including procedures that ensure that versions are controlled and only approved changes are implemented. The project implements aspects of change control necessary to continuously manage changes to project deliverables. Some organizations implement a Change Control Board to formally address change approval issues to ensure the project baseline is maintained by only allowing approved changes into the documentation or product.

The project manager must integrate his or her monitoring and controlling activities to provide feedback to the executing process. Some information will be feedback to the planning process. However, if there is a high-impact change to the project scope or overall plan, then there will also be input to the initiating processes.

The closing processes require the project manager to develop all procedures required to formally close a project or a phase.6 This group of processes covers the transfer of the completed product to the final customer and project information to the appropriate organization within the company. The procedure will also cover the closure and transfer of an aborted project and any reasons the project was terminated prior to completion.

The process groups described above represent the standard processes defined by the PMBOK® Guide, Fourth Edition, required for every project.7 These processes indicate when and where to integrate the many knowledge areas to produce a useful Project Management Plan. Those processes, when executed, will produce the result defined by the project’s scope. Chapters 7 through 15 of this Handbook, and their supplementary readings, describe specific details for applying each knowledge area.

REFERENCES

1 Project Management Institute, A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge, Third Edition, Project Management Institute, 2004: p. 30.

2 Project Management Institute, A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge, PMBOK® Guide, 2000 Edition, Project Management Institute, 2000: p. 29.

3 Project Management Institute, A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge, Fourth Edition, Project Management Institute, 2008: p. 31.

4 Ibid., p. 34.

5 Ibid., p 36.

6 Ibid., p. 54.

7 Ibid., p 31.