CHAPTER 4

Initiation Strategies for Managing Major Projects

The initiation of a project largely determines how successful it will be. The crucial point about the model presented in this chapter is that all the items must be considered from the outset if the chances of success are to be optimized. The project must be seen as a whole, and it must further be managed as a whole. While our focus here is on large, broad, community-based projects, the same principles apply, on a lesser scale, to other projects.

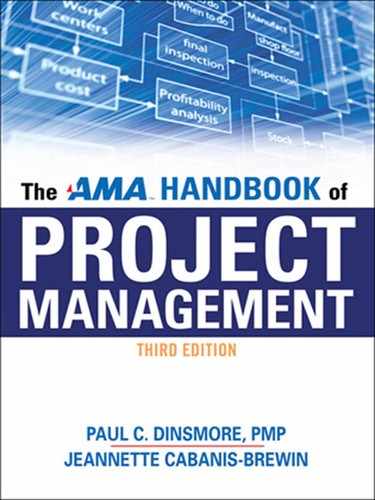

The strategic model for managing projects discussed in this chapter is shown in Figure 4-1. Its logic is essentially as follows:

• The project is in danger of encountering serious problems if its objectives, general strategy, and technology are inadequately considered or poorly developed, or if its design is not firmly managed in line with its strategic plans.

• The project’s definition both affects and is affected by changes in external factors (such as politics, community views, and economic and geophysical conditions), the availability of financing, and the project duration. Therefore, this interaction must be managed actively. (Many of these interactions operate through the forecasted performance of the product that the project delivers once completed.)

• The project’s definition; its interaction with these external, financial, and other matters; and its implementation are harder to manage and possibly damagingly prejudiced if the attitudes of the parties essential to its success are not positive and supportive.

FIGURE 4-1. STRATEGIC MODEL FOR MANAGING PROJECTS

Realization of the project as it is defined, developed, built, and tested involves:

• Deciding the appropriate project-matrix-functional orientation and balancing the involvement of the owner, as operator, and the project implementation specialists.

• Having contracts that reflect the owner’s aims and that appropriately reflect the risks involved and the ability of the parties to bear these risks.

• Establishing checks and balances between the enthusiasm and drive of the project staff and the proper conservatism of its sponsors.

• Developing team attitudes, with emphasis put on active communication and productive conflict.

• Having the right tools for project planning, control, and reporting.

Let us examine these points in more detail.

PROJECT DEFINITION

The project should be defined comprehensively from its earliest days in terms of its purpose, ownership, technology, cost, duration and phasing, financing, marketing and sales, organization, energy and raw materials supply, and transportation. If it is not defined properly “in the round” like this from the outset, key issues essential to its viability could be missed or given inadequate attention, resulting in a poor or even disastrous project later.

Objectives

The extent to which the project’s objectives are not clear, are complex, do not mesh with longer term strategies, are not communicated clearly, or are not agreed upon compromises the chances of its success. The Apollo program, which placed the first man on the moon, was technically extremely difficult, but its chances of success were helped by the clarity of its objective.

It is interesting to compare the Apollo program with a later U.S. plan for a permanent, manned space station orbiting the earth. The space station objective was superficially clear—in former President Ronald Reagan’s words, “to develop a permanently manned space station and to do it within a decade.” But the objective is in fact far from clear. What, for example, does develop really mean? Just design and construct? Surely not. And what is the station’s real mission—and hence, what is the project’s proper development strategy? Earth observation? A way station to planetary observation? Experimental purposes? A combination of these? The space station example illustrates that project, or program, objectives should match with viable long-term strategies, otherwise there will be confusion, uncertainty, changes, cost increases, and delays—as there indeed have been.

Strategy

Strategies for the attainment of the project objectives should similarly be developed in as comprehensive a manner as possible, right from the outset. This means that at the prefeasibility and feasibility stages, for example, industrial relations, contracting, communications, organization, and systems issues should all be considered, even if not elaborated on, as well as the technical, financial, schedule, and planning issues.

Some of the most valuable work on the need for comprehensive planning has come from the areas of R&D and new product development. Valuable work has also been done with regard to development aid projects. The insights of Cassens, Morris, and Paul encapsulate almost everything anyone of good sense would expect regarding what it takes to produce successful development projects.2 The writings of Cooper, Manfield, and others on new product development similarly relate product implementation performance to environmental and market success.3

Technology and Design

The development of the design criteria and the technical elements of the project should be handled with the utmost care. The design standards selected affect both the difficulty of construction and the operating characteristics of the plant. Maintainability and reliability should be critical factors in determining the project’s operating characteristics. Many studies have shown that technical problems have a huge impact on the likelihood of project overrun.4 Thorough risk analysis is therefore essential. The rate of technological change in all relevant systems and subsystems should be examined; technology must be tested before being designed into production (as opposed to prototype) projects; and design changes should be kept to a minimum.

No design is ever complete; technology is always progressing. A central challenge in the effective management of projects is thus the conflict between meeting the schedule and the desire to get the technical base that fits better. The orderly progressing of the project’s sequence of review stages—the level of detail becoming progressively tighter, with strict control of technical interfaces and of proposed changes (through configuration management)—is now a core element of modern project management.

Projects as different as weapons systems, process plants, and information systems now generally employ project development methodologies that emphasize careful, discrete upgrading of technology; thorough review of cost, schedule, and performance implications; and rigorous control of subsequent proposed changes.

A major issue in project specification is how great a technological reach should be aimed for without incurring undue risks of cost overruns, schedule slippages, or inadequate technical performance. This was once the most difficult issue to get right on projects. More recently, practice has improved (though there have still been some spectacular disasters), partly because our basic technologies are not progressing into new domains at the rate they were before, but also partly because of the greater caution, care over risk assessment, use of prototypes, etc., that are now more common project practices. It is barely conceivable that we should embark on a brand new nuclear power reactor (AGR) or aerospace project (Concorde) today with the bravura that we did twenty to thirty years ago.

In setting up projects, then, care should be taken to appraise technological risk, prove new technologies, and validate the project design before freezing the design and moving into implementation.

EXTERNAL FACTORS, FINANCE, AND DURATION

Many external factors affect a project’s chances of success. Particularly important are the project’s political context, its relationship with the local community, the general economic environment, its location, and the geophysical conditions in which it is set.

Political, Environmental, and Economic Factors

Project personnel have often had difficulty recognizing and dealing with the project’s impact on the physical and community environment and, in consequence, managing the political processes that regulate the conditions under which projects are executed. Most projects raise political issues of some sort and hence require political support: moral, regulatory, and sometimes even financial. National transportation projects, R&D programs, and many energy projects, for example, operate only under the dictate of the politician. The civil nuclear power business, Third World development projects, and even build-own-operate projects require political guidance, guarantees, and encouragement.

Do nonmajor projects also need to be conscious of the political dimension? Absolutely. Even small projects live under regulatory and economic conditions directly influenced by politicians. Within the organization, too, project managers must secure political support for their projects.

Therefore, these political issues must be considered at the outset of the project. The people who and the procedures that are to work on the project must be attuned to the political issues and ready to manage them. To be successful, project managers must manage upward and outward, as well as downward and inward. The project manager should court the politicians, helping allies by providing them with the information they need to champion his or her program. Adversaries should be co-opted, not ignored. (The environmental impact assessment process, which will be described shortly, shows how substantive dialogue can help reduce potential opposition.)

Although environmentalism has been seriously impacting project implementation since the 1960s, most project personnel ignored it as a serious force at least until 1987–1988, when a number of world leaders, the World Bank, and others began to acknowledge its validity. Now, at last, most project staff members realize that they must find a way of involving the community positively in the development of their project. Ignoring the community and leaving everything to planning hearings is often to leave it too late. A “consent strategy” should be devised and implemented.4 Dialogue must begin early in the project’s development.

In a different sense, getting the support of the local community is particularly important in those projects where the community is, so to speak, the user—as, for example, in development projects and information technology. The local community may also be the potential consumer or purchaser for the project. Doing a market survey to see how viable the project economics are is thus an essential part of the project’s management.

Changes in economic circumstances affect both the cost of the project’s inputs and the economic viability of its outputs. The big difference today compared to thirty years ago is that then we assumed conditions would not vary too much in the future. Now we are much more cautious. As with technology, then, so with economics, we should be more cautious in appraising and managing our projects today.

In the area of cost-benefit discounting and other appraisal techniques, practice has moved forward considerably over the last few years. Externalities and longer term social factors are now recognized as important variables that can dramatically affect the attractiveness of a project. Old project appraisal techniques have been replaced with a broader set of economic and financial tools in the community context with the use of environmental impact assessment procedures.

Initially resisted by many in the project community, the great value of environmental impact assessment (EIA) is that it (1) allows consultation and dialogue among developers, the community, regulators, and others; and (2) forces time to be spent at the front end in examining options and ensuring that the project appears viable. Through these two benefits, the likelihood of community opposition and of unforeseen external shocks arising is diminished. Further, in forcing project developers to spend time planning at the front end, the EIA process emphasizes precisely the project stage that traditionally has been rushed, despite the obvious dangers. We all know that time spent in the project’s early stages is time well spent—and furthermore, that it is cost-effective time well spent—yet all too frequently this stage is rushed.

Finance

During the 1980s, there was a decisive shift from public sector funding to the private sector, under the belief that projects built under private sector funding inevitably demonstrate better financial discipline. This is true when projects are built and financed by a well-managed private sector company. But private financing alone does not necessarily lead to better projects (as the record of Third World lending shows: weak project appraisals, loan pushing, cost and schedule overruns, white elephants, etc.). What is required is funding realism. The best way to achieve this is by getting all parties to accept some risk and to undertake a thorough risk assessment. Full risk analysis of the type done for limited recourse project financing, for example, invariably leads to better set up projects and should therefore be built into the project specification process. The use of this form of funding in methods such as build-own-operate projects has had the healthy consequence of making all parties concentrate on the continuing economic health of the project by tying their actions together more tightly to that goal.

The raising of the finance required for the English Channel Tunnel is a classic illustration of how all the elements shown in Figure 4-1 interact—in this case, around the question of finance: How to raise the necessary billions of pounds required so that certain technical work could be done, planning approvals be obtained, contracts be signed, political uncertainties be removed, etc. Because the project was raising most of its funding externally, there was a significant amount of bootstrapping required. The tasks could be accomplished only if some money was already raised, and so on. Actions had to be taken by a certain time or the money would run out. Furthermore, a key parameter of the project’s viability was the likelihood of its slippage during construction. A slippage of three to six months meant not just increased financing charges, but the lost revenue of a summer season of tourist traffic. The English Channel Tunnel thus demonstrates also the significance of managing a project’s schedule and of how its timing interrelates with its other dimensions.

Duration

Determining the overall timing of the enterprise is crucial to calculating its risks and the dynamics of its implementation and management. How much time one has available for each of the basic stages of the project, together with the amount and difficulty of the work to be accomplished in those phases, influences the nature of the task to be managed.

In specifying the project, therefore, the project manager spends considerable effort ensuring that the right proportions of time are spent within the overall duration. Milestone scheduling of the project at the earliest stage is crucial. It is particularly important that none of the development stages of the project be rushed or glossed over—a fault that has caused many project catastrophes in the past. A degree of urgency should be built into the project, but too much may create instability.

It is best to avoid specifying that implementation begin before technology development and testing is complete. This is the “concurrency” situation. Concurrency of course is sometimes employed deliberately to get a project completed under exceptionally urgent conditions, but it often brings problems in redesign and reworking. If faced with this, analyze the risk rigorously, work breakdown element by work breakdown element, and milestone phase by milestone phase.

The concurrency situation should be distinguished from a similar sounding but different “fast-build” practice. (This is sometimes also known as “fast track,” but others equate fast track with concurrency. The terminology is imprecise and, hence, there is confusion—and danger—in this area.) Fast build is now being used to distinguish a different form of design and construction overlap: that where the concept, or scheme, design is completed but then the work packages are priced, scheduled, and built sequentially within the overall design parameters, with strict change (configuration) control being exercised throughout. With this fast build situation, the design is secure and the risks are much less.

The lessons learned on dealing with the challenge of managing urgent projects include:

• Do not miss any of the stages of the project.

• Use known technology and/or design replication as far as possible; avoid unnecessary innovation.

• Test technology before committing to production (prototyping). Avoid concurrency unless prepared to take the risk of failing and of having to pay for the cost of rework.

• Avoid making technical or design changes once implementation has begun. Choose design parameters broad enough to permit development and detailing without subsequent change (fast build). Exert strict change control/configuration management.

• Order long-lead items early.

• Prefabricate and/or build in as predictable an environment as possible and get the organizational factors set to support optimum productivity. Put in additional management effort to ensure the proper integration at the right time of the things that must be done to make the project a success: teamwork, schedule, conscious decision-making, etc.

Each of these areas, then—external factors, finance, and duration—is both affected by and affects the viability of project definition.

ATTITUDES

Implementation can be effective only if the proper attitudes exist on the project. Unless there is a commitment toward making the project a success, unless the motivation of everyone working on the project is high, and unless attitudes are supportive and positive, the chances of success are substantially diminished.

Commitment and support at the top are particularly important; without it the project is severely jeopardized. But while commitment is important, it must be commitment to viable ends. Great leaders can become great dictators. Therefore, if sane, sensible projects are to be initiated, they must not be insulated from criticism. Critique the project at its specification stage, therefore, and ensure that it continues to receive objective, frank reviews as it develops.

IMPLEMENTATION

Project management has been, in the past, concerned primarily with the process of implementation. This implies that developing the definition of the project is somehow not the concern of the project’s manager. This could not be further from the truth.

The key conceptual point is not only that the specification process must be actively managed, but that the specification process must consider all those factors that might prejudice its success—not just technical matters and economics, but also ecological, political, and community factors and implementation issues.

Organization

Two key organizational issues in projects are deciding the relevant project-matrix-functional orientation and the extent of owner involvement. Both of these must be considered from the earliest stages of project specification.

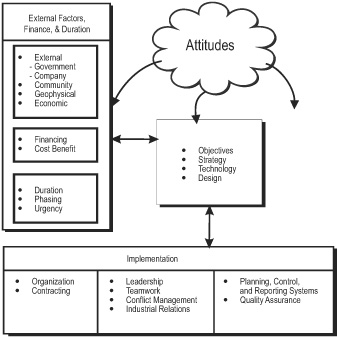

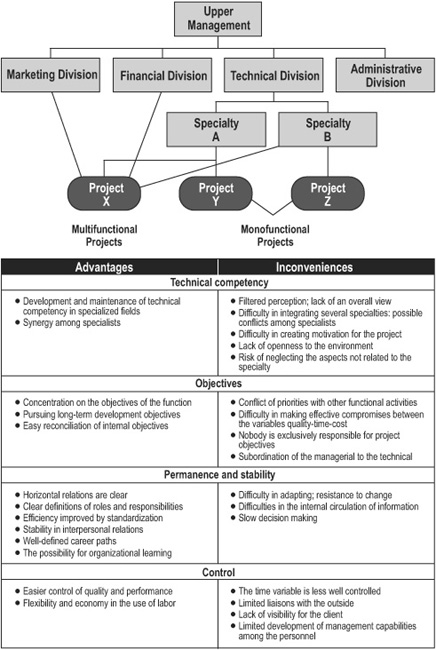

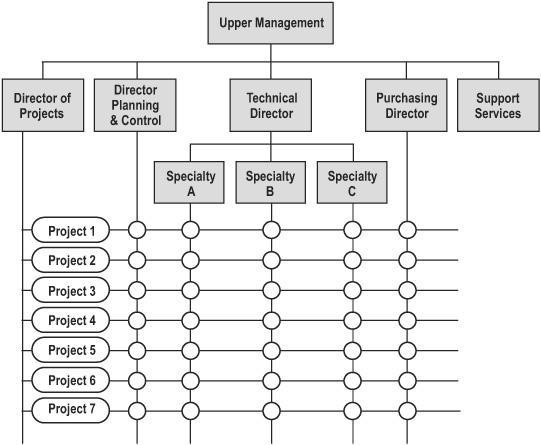

A fully “projectized” orientation is expensive in resource terms. Many projects start and finish with a functional orientation but “swing” to a matrix during implementation.5 Note too that implementing a matrix takes time and that effort must be put into developing the appropriate organizational climate. Assistance from the area of organization behavior therefore should be considered when designing and building a matrix organization. (Indeed, this is also true for other forms of project organization.) Figures 4-2 through 4-4 display the characteristics of each of these types of project organizations.

The crucial issues with regard to the extent of owner involvement are the extent that the owner (1) does not have the resources, or (2) does not have the skills, outlook, or experience, but (3) has legal or moral responsibility for assuring implementation of satisfactory standards. The first constraint is the most common. In building and civil engineering, for example, because of the nature of the demand, the owner rarely, if ever, has sufficient resources in-house to accomplish the project. Outside resources—principally designers, contractors, and suppliers—have to be contracted in. The owner focuses more on running the business.

Yet some degree of owner involvement is generally necessary. For if no project management expertise is maintained in-house, then active, directive decision-making of the kind that projects generally require is not available. On the other hand, if operators who are not really in the implementation business get too heavily involved in it, then there is a danger that the owner’s staff may tinker with and refine design and construction decisions at the expense of effective project implementation. The solution to this dilemma is not easy to determine. There is no standard answer. What is right will be right for a given mix of project characteristics, organizations, and personalities.

The key point, ultimately, is for owner-operators to concentrate on predetermined milestone review points—the markers in the project’s development at which one wants the project to have satisfactorily reached a certain stage—and to schedule these properly and review the project comprehensively as it passes across each of them. Milestone scheduling by owners is in fact now much more accepted as appropriate rather than the more detailed scheduling of the past.

Contract Strategy

The degree of owner involvement is related to the contractual strategy being developed. It is now generally recognized that the type of contract—essentially either cost reimbursable or incentive (including fixed price)—should relate to the degree of risk the contractor is expected to bear. If the project scope is not yet clear, it is better not to use an incentive or fixed-price-type contract: The contract can be converted to this form later. Contracts should be motivational: Top management support and positive attitudes should be encouraged.

The parties to a contract should put as much effort as possible, as early as possible, into identifying their joint objectives. While competitive bidding is healthy and to be encouraged, adequate time and information must be provided to make the bid as effective as possible. Spend time, too, ensuring that the bases upon which the bid is to be evaluated are the best: Price alone is often inadequate.

People Issues

Projects demand extraordinary effort from those working on them, often for a comparatively modest financial reward—and with the ultimate prospect of working oneself out of a job! Frequently, significant institutional resistance must be overcome in order for the many factors here being listed to be done right. This puts enormous demands on the personal qualities of all those working on the project, from senior management to the professional team(s) to the work force.

The roles of project manager, leader, champion, and sponsor should be distinguished. Each is needed throughout the project, but the initial stages particularly require the latter three. Beware of unchecked champions and leaders, of the hype and overoptimism that too often surround projects in their early stages. The sponsor must be responsible for providing the objective check on the feasibility of the project. (For more on these roles, see Chapter 13A on stakeholder management.)

FIGURE 4-2. CHARACTERISTICS OF THE FUNCTIONAL STRUCTURE

The functional structure is a widespread organizational form. It is characterized by a hierarchical, “chain-of-command” power structure and specialization into functional “silos.” Adapted from Brain Hobbs and Pierre Menard, “Organizational Choices for Project Management,” AMA Handbook of Project Management, First Edition, AMACOM 1993: pp 85 and 88.

INCONVENIENCES |

|

Clear identification of overall project responsibility |

Duplication of effort and resources |

Good systems integration |

Limited development and accumulation of know-how |

More direct contact amongdifferent disciplines |

Employment instability |

Clear communications channels with client and other outside stakeholders |

|

Clear priorities |

|

Effective trade-offs among cost, schedule, and quality |

May tend to sacrifice technical quality for the more visible variables of schedule and cost |

Client-oriented |

|

Results-oriented |

|

FIGURE 4-3. CHARACTERISTICS OF THE FULLY PROJECTIZED STRUCTURE

The fully projectized structure makes projects independent from the rest of the organization, gives the project manager full authority over resources, and facilitates the development of multidisciplinary technical terms. Adapted from Brian Hobbs and Pierre Menard, “Organizational Choices for Project Management,” AMA Handbook of Project Management, First Edition, AMACOM 1993: p 90.

We should recognize the importance of team working, of handling positively the conflicts that inevitably arise, and of good communications. Consideration should be given to formal start-up sessions at the beginning of a team’s work (mixing planning with team building). The composition of the team should be looked at from a social angle as well as from the technical: People play social roles on teams and these must vary as the project evolves.

All projects involve conflict: Cost, schedule, and technical performance are in conflict. However, conflict can be used positively as a source of creativity. Conflict is managed in this way on the best projects. On some projects it is ignored or brushed over. At best, a creative tension is then lost; at worst, it becomes destructive.

Every effort should be made to plan for improved productivity and industrial relations. The last twenty years have seen considerable improvements in industrial relations, although much remains to be done. Productivity improvements still represent an area of major management attention. Total quality management (TQM), with its emphasis on determining real needs and of improving performance “continuously,” has perhaps been one of the most potent concepts in this regard.6

FIGURE 4-4. THE MATRIX STRUCTURE

The matrix structure seeks to combine the advantages of the functional and the projectized organization, while avoiding their disadvantages. Project and functional components are administratively independent, but interdependent in the execution of projects. Adapted from Brian Hobbs and Pierre Menard, “Organization Choices for Project Management,” AMA Handbook of Project Management, First Edition AMACOM 1993: p 91.

Planning and Control

Plans should be prepared by those technically responsible for them and integrated by the planning and control group. Planning initially should be at a broad systems level with detail being provided only where essential and in general on a rolling wave basis. Similarly for cost: Estimates should be prepared by work breakdown element, detail being provided as appropriate. Cost should be related to finance and be assembled into forecast out-turn cost, related both to the forecast actual construction price and to the actual product sales price.

Implementation of systems and procedures should be planned carefully so that all those working on the project understand them properly. Start-up meetings should develop the systems procedures in outline and begin substantive planning while simultaneously building the project team.

STRATEGIC ISSUES FOR ENTERPRISES WORKING ON PROJECTS

The model presented in Figure 4-1 is of course a high-level one; it is bound to be as its essence is its comprehensiveness. Note, therefore, that as one gets into any particular subsystem, the level of detail increases. The two subsystems where models have more commonly been developed in detail are financing and implementation; that is, the areas traditionally discussed as project management.

For the management of projects, then, a strategic model can be said to exist. But what are the chances of anyone ever implementing it? The key is in changing perceptions; and the keys to effecting that are management and education.

The difficulty with project management is that it can encompass such a broad scope of services in different situations. The project manager for an equipment supply contractor on a power station, say, has a more narrowly defined task than the utility’s overall project manager. The project manager for the specification, procurement, and installation of a major telecommunications system has a much broader scope than the project manager of a software development program. Yet all involve the elements of Figure 4-1 in some way.

The two strategic questions for enterprises working in project-related industries are to determine:

1. The level and scope of services that one’s clients and customers need and are able to buy.

2. Whether one has the organizational capability to supply this level and scope of services.

There is little doubt that the most powerful set of ideas relevant to the first question—the level of services—is that of total quality. The TQM concept forces one to analyze what services one’s clients want. (And there may be several different sets of clients in the production chain ranging from one’s boss or bosses to, most obviously, the people who are using the services, whether as customers or as colleagues.) This approach to analyzing the effectiveness of one’s services is directly relevant to determining not just the extent to which the factors identified in Figure 4-1 are needed, but also the extent to which they need to be organized and delivered in an integrated fashion.

As long ago as 1959, the Harvard Business Review identified integration as the key project management function.7 The question is, however, what needs to be integrated? By fundamentally addressing the client’s real needs and the extent to which these are being satisfactorily met, a project manager may see, for example, that on this project the supply of finance, or the ability to provide better value for money, or to build faster, or to provide greater technical reliability, are issues that need better integration within the scope of project services to be provided.

As the level and scope of services become clearer, the second key strategic question arises: that of the organization’s ability to deliver. Here, the principal difficulty is that our educational institutions are so far producing people with either a severely limited capability to envision or manage the broad array of issues outlined in Figure 4-1. For projects to be managed successfully, a wide range of factors may need integrating. Few people have any training across such a broad array, particularly in a project context. Yet there are signs that times are changing, and it is surely very much in the interests of all who work in project-related industries to support such change. The inclusion of Integration Management as a knowledge area in PMI’s body of knowledge—an addition that was made since the first edition of this Handbook was published—is one sign of the trend toward greater emphasis on the integrative function of the project manager.

The second evidence of an increasing maturity of project management formation is the growing number of advanced project management educational programs, particularly at the postgraduate level. Postgraduate education is important because a considerable level of technical, organizational, and business integration is being required at senior levels on most of the more advanced projects and programs. Without a well-rounded educational background, as well as real frontline practical experience, there must be some doubt as to our ability to furnish managers capable of meeting the project management demands being made by today’s projects.

CONCLUSION

A fundamental task facing any senior manager on a major program or project is to work out how the various factors identified in Figure 4-1 should best be allocated and integrated on his or her project. For managers and educators, a major challenge facing the project management profession is to ensure that we have people with the intellectual breadth and the experience to tackle issues of the diversity and subtlety of those so often posed by today’s projects. Every encouragement should be given to the professional societies and the schools and other organizations around the world to develop an appropriate, well-rounded professional formation for the management of projects.

REFERENCES

1 A. O. Hirschman. Development Projects Observed. Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution, 1967.

2 R. Cassens, and Associates. Does Aid Work? Oxford, England: Clarendon Press, 1986; J. Moris. Managing Induced Rural Development. Bloomington, Ind.: International Development Institute, 1981; S. Paul. Managing Development Programs: The Lessons of Success. Boulder, Colo.: Westview Press, 1982.

3 N. R. Baker, S. G. Green, and A. S. Bean. “Why R&D Projects Succeed or Fail.” Research Management (November-December 1986), pp. 29–34; R. Balachandra and J.A. Raelin. “When to Kill That R&D Project.” Research Management (July-August 1984), pp. 30–33; R. G. Cooper. “New Product Success in Industrial Firms.” Industrial Marketing Management 11 (1982), pp. 215–223; A. Gerstenfeld. “A Study of Successful Projects, Unsuccessful Projects and Projects in Progress in West Germany.” IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management (August 1976), pp. 116–123; E. Manfield, and S. Wagner. “Organizational and Strategic Factors Associated With Probabilities of Success and Industrial R&D.” Journal of Business 48, No. 2 (April 1975); R. Whipp, and P. Clark. Innovation and the Auto Industry, London, England: Francis, 1986. See also F. P. Brooks. The Mythical Man-Month. Reading, Mass.: Addison-Wesley, 1982; T. E. Harvey. “Concurrency Today in Acquisition Management.” Defense Systems Management Review 3, No. 1 (Winter 1980), pp. 14–18; O. P. Karhbanda, and E. A. Stalworthy. How to Learn From Project Disasters. London, England: Gower, 1983; Learning From Experience: A Report on the Arrangements for Managing Major Projects in the Procurement Executive. London, England: Ministry of Defense, 1987; E. W. Merrow. Understanding the Outcomes of Mega Projects: Quantitive Analysis of Very Large Civilian Projects. Santa Monica, Calif.: Rand Corporation, March 1988.

4 B. Bowonder. “Project Siting and Environmental Impact Assessment in Developing Countries.” Project Appraisal 2, No. 1 (March 1987), pp. 1–72; N. Lichfield. “Environmental Impact Assessment in Project Appraisal in Britain.” Project Appraisal 3, No. 3 (September 1988), pp. 125–180; J. Stringer. Planning and Inquiry Process. MPA Technical Paper No. 6, Templeton College, Oxford, September 1988.

5 P. W. G. Morris. “Managing Project Interfaces—Key Points for Project Success.” In D. I. Cleveland and W. R. King, eds., Project Management Handbook. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1988; C. E. Reis de Carvalho, and P. W. G. Morris. “Project Matrix Organizations, or How to Do the Matrix Swing.” 1979 Proceedings of the Project Management Institute, Los Angeles. Drexel Hill, Penn.: 1979.

6 W. E. Deming. Out of Crisis. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press 1989; M. Imai. Kaizen. New York: Kaizan Institute/Random House, 1986; J. M. Juran, and F. M. Gryna. Juran’s Quality Control Handbook. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1988.

7 P. O. Gaddis. “The Project Manager.” Harvard Business Review (May–June 1959), pp. 89–97.

8 “Project Managers and Their Teams: Selection, Education, Careers.” Proceedings of the 14th International Experts Seminar, INTERNET, March 15–17, 1990, Zurich, Switzerland. See particularly the papers by R. Archibald and A. Harpham; E. Gabriel; and R. Pharro and P. W. G. Morris.