5

Negotiation: The Open Approach to Conflict Resolution

Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter, you should be able to:

• Define negotiation and describe how it can help resolve conflicts.

• Describe the five styles of conflict resolution and identify which one you use most often.

• Explain the advantages and disadvantages of the forcing, compromising, and collaborating negotiating orientations.

• Describe the four most important elements of principled negotiation and how to put these into action.

• Describe five ways to handle angry, hostile, or inflexible disputants to get them to participate in the principled negotiation approach to conflict resolution.

INTRODUCTION

We have been discussing negotiation in the form of principled negotiation throughout this course. It is now time to pay more attention to exactly what is meant by the term and to explore this concept more fully.

NEGOTIATION

Negotiation is a way to get what you want or need from other people. Consider the following definitions of negotiation.

1. Negotiation is to confer or discuss with another person or persons with a view toward reaching agreement (Allen 1990, 794).

2. Creative negotiation is a process whereby two or more parties meet and, through artful discussion and imagination, confront a problem and arrive at an innovative solution that best meets the needs of all parties and secures their commitment to fulfilling the agreement reached (Shea 1983, 19).

3. Negotiation is a back-and-forth communication used to reach an agreement when you and the other side have some interests that are shared and others that are opposed (Fisher et al. 1991, 17).

4. Negotiation is essentially a mutual influence attempt process—it’s all about trying to influence another person or group of people to do something or give you something you want (Babcock and Laschever 2003, 141).

These four definitions suggest some fundamental facts about negotiation. First, negotiation is a process, commonly used both inside and outside of organizations. It is also a skill, and because it is a skill, not everyone is going to be proficient at it. Finally, negotiation is a useful way to solve a problem or conflict that exists between two or more parties. It is this aspect of negotiation—its use as a conflict resolution instrument—that we will examine in this chapter.

CONFLICT RESOLUTION APPROACHES

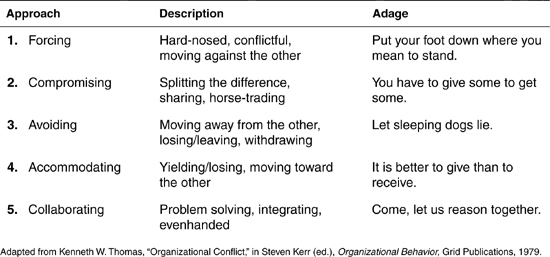

In Chapter 1, we stated that a conflict resolution approach is the method and manner in which a person attempts to eliminate or minimize a dispute between parties. As we elaborated this concept, we identified five basic approaches to conflict resolution. In order to determine your approach to conflict resolution, turn to the following Think About It exercise. Although people often adjust their approach to the circumstances with which they’re confronted, they have a tendency to use one conflict resolution approach more than the others (see Tool 1–1). A brief description of each approach is given here and in Exhibit 5–1. The numbers in this list correspond to those in Exercise 5–1.

1. Forcing occurs when one or both sides attempt to satisfy their own needs regardless of the impact on the other side.

2. Compromising exists when both sides gain and lose in order to resolve the conflict.

3. Avoiding emerges when one or both sides recognize that a conflict exists, but react by withdrawing from or postponing the conflict.

4. Accommodating occurs when one side resolves a conflict by giving in to the other side at the expense of his or her own needs.

5. Collaborating exists when an attempt is made by one or both parties to satisfy fully the needs of both parties.

To determine your approach to or style of conflict resolution, read the following five statements. Circle the number of the approach that best represents your style, even if you do not follow this approach all the time.

1. I am generally firm in pursuing my goals. I try to show others the logic of my position and its benefits. If they are equally committed to their position, I make a strong effort to get my way by stressing my points. I give in reluctantly.

2. I try to find a middle-ground solution. I am willing to give up some points if it will lead to a fair combination of gains and losses for both parties. To expedite the resolution, I generally suggest that we search for a compromise, instead of stubbornly holding on to my position.

3. I try to avoid the debilitating tensions associated with disagreements by letting others take responsibility for solving the problem. If possible, I postpone dealing with the problem until I can cool off and take time to think it over. To reduce the likelihood of conflicts, I often avoid taking controversial positions, and I try not to get uptight when others express positions different from my own.

4. I try to soothe the feelings of the other party, so the disagreement doesn’t damage our relationship. I try to diffuse the conflict by focusing on points of agreement. If the other person’s position seems very important to him or her, I will probably concede my own to maintain harmony.

5. I attempt to get other parties to air their concerns and discuss the issues. I describe my position frankly and ask the other person to do the same. I favor a direct discussion of conflicting views as a way of forging an agreement. It is not always possible, but I try to satisfy the sides of both parties.

Adapted from David A. Whetten and Kim S. Cameron, Developing Management Skills, Addison Wesley Longman, 1984.

No single conflict resolution approach is optimal in every situation. Different circumstances call for different approaches. Generally, collaborating is considered a good approach, and forcing, particularly if used against you, is considered a bad approach.

In one major study, Kenneth W. Thomas and Louis R. Pondy asked sixty-six managers to recall a recent conflict, to state which conflict resolution approach they and the other parties used, and to describe how they behaved when resolving the conflict. Exhibit 5–2 presents the results of this research. From this exhibit, differences in perceptions can be seen. The executives tended to see themselves as “cooperative, collaborating, and willing to compromise.” However, they tended to see the other side as “uncooperative and hard-nosed.” When asked to identify specific behaviors used by both parties, they usually described their own behavior as “informing, suggesting, and reminding,” but described the other side’s behavior as “unreasonable, demanding, and refusing” (Thomas and Pondy 1977).

In their conclusions, the researchers suggested that four perceptual factors may contribute to this bias. First, each person tends to be more aware of the reasons behind his or her own behavior than the reasons behind the other person’s. Another person’s annoying and frustrating words and actions seem more arbitrary and unreasonable than one’s own words and actions. Second, each manager needs to view his or her own behavior in positive, complimentary terms, which is understandable, because most people like to view themselves in this way. Third, aggressive and forceful words and actions are more likely to be remembered than cooperative gestures because they’re threatening; they can also lead to an exaggerated impression of the other person’s aggressiveness. Fourth, each person notices his or her own forceful behavior less than the other side’s because individuals can neither see their own facial expressions nor hear their own intonations as clearly as they can see and hear others’.

![]() xhibit 5–2

xhibit 5–2

Distribution of How Sixty-Six Managers Viewed Their Own and Others’ Styles of Conflict Resolution (by Percentage)

THE CONNECTION BETWEEN NEGOTIATION AND CONFLICT RESOLUTION APPROACHES

Negotiation, the two-way communication used to reach an agreement, is one method frequently used to resolve conflict. Negotiators can adopt a forcing, compromising, avoiding, accommodating, or collaborating style as they engage in this bargaining. But as Exhibit 5–2 graphically indicates, managers are likely to use three key approaches when involved in negotiations: forcing, compromising, and collaborating. Therefore, we will concentrate on these three approaches. To illustrate these different negotiating styles more clearly, consider the following statements made by experienced negotiators:

Negotiator A advocates the forcing approach; B is a compromiser; and C is a collaborator, integrator, and problem solver. All three approaches have their advantages and disadvantages. Exhibit 5–3, in conjunction with Tool 1–1, reveals when each approach is appropriate and inappropriate.

Because negotiating is a method of resolving conflict, individuals interested in dealing effectively with conflict should develop their negotiating skills. But, first, they must understand the different negotiating approaches and the conditions under which they work best. Review Exhibit 1–1, Tool 1–1, and Exhibit 5–3 for several minutes before continuing.

As a general rule, forcing works best when time is limited and the negotiator has more power than the other side. With this style, one person tries to force his or her solution onto the other side. If the other side is also attempting to force matters, negotiations might easily lead to a stalemate. A disadvantage of this approach is that the winner sometimes creates a bitter, resentful adversary out of the loser.

Most people adopt a compromising approach. In fact, negotiation is often defined as the process of compromising in order to reach agreement. This style is considered fair because both sides win and lose some points. But a disadvantage of this approach is that it encourages both sides to take extreme positions. Because the negotiating process progresses to a middle-ground position, most negotiators start with exaggerated demands. And in their haste to reach agreement, compromise-oriented negotiators sometimes miss opportunities to resolve conflict in mutually advantageous ways.

Think about a recent negotiation that you were part of or witnessed. Which of the three negotiating styles—forcing, compromising, or collaborating—best characterizes it? Was the outcome positive or negative? Or did it have elements of both?

_____________________________________________

_____________________________________________

_____________________________________________

_____________________________________________

_____________________________________________

_____________________________________________

By collaborating, negotiators strive to reach an agreement in which both sides win. By seeking solutions that maximize gains for all, negotiators create a totally different process. Instead of creating an adversarial situation, collaborators work together to find solutions that will make both sides happy. This approach leads to excellent personal relationships between the two sides. Yet it can be very time-consuming and might encourage one side to take advantage of a presumed weakness in the negotiating approach. This is most likely to occur if one person has a strong forcing orientation.

While there are advantages and disadvantages to each negotiating approach, we will emphasize the value of collaboration in the remainder of this chapter. Although this approach is the most difficult to learn and master, it can be the most beneficial to those trying to resolve a conflict. Whereas some negotiating approaches, such as compromising, encourage negotiators to exaggerate their initial positions, collaboration encourages all involved parties to be honest and direct, without being overly critical of one another. Think about how our discussion of negotiating styles can be incorporated into your own life experience.

THE MASOON COMPANY: A CASE STUDY

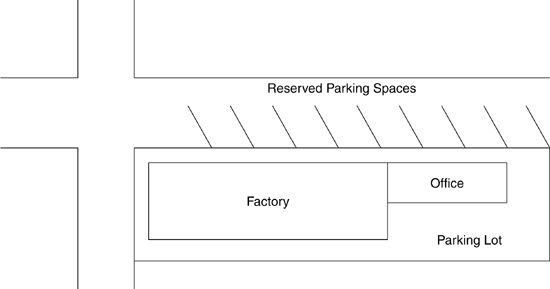

To understand how the negotiating process works, let’s examine the situation presented in Exhibit 5–4 and apply some basic principles to it. Clearly, there is a definite and potentially significant conflict brewing between the HR manager, representing the Masoon Company, and the new union president, representing the union (apparently its most militant faction). Conflict has been defined as a process that begins when one party perceives that another has negatively affected, or is about to negatively affect, something that he or she cares about. By parking in the reserved area, the new union president is negatively affecting the work goals of the HR manager. The HR manager undoubtedly wants to maintain a stable employer-employee relationship, and the new union president’s behavior has upset this relationship. But how should the HR manager deal with this conflict? Take a few minutes to respond to the questions in Exercise 5–2.

![]() xhibit 5–4

xhibit 5–4

The Case of the Reserved Parking Spaces

Masoon Company manufactures machine tools. About a year ago, it moved its facilities from the Boston area to an empty factory in a small New England town that has been experiencing high unemployment. In appreciation, the town council removed parking meters from about a dozen diagonal parking spaces in front of the plant and put up a sign that read: “Reserved for Visitors and Executives of the Masoon Company.” Certain company executives park regularly in the reserved spaces, while others (in some unspecified but carefully observed pecking order) park in the lot behind the office. Salespeople and visitors do the same when the spaces in front are occupied. Here is a diagram of the factory and office location.

The company is unionized and has enjoyed a long, harmonious relationship with its union, formerly under the leadership of a group of older employees who moved with the company to its new location. There has never been a strike. Shortly before negotiations were to begin for a new contract, however, one of the younger, locally hired employees won the union’s presidency in a hotly contested election.

The day after the election, the new union president parked his ten-year-old car in one of the reserved spaces alongside the shiny, late-model cars of company executives. Before the end of the day, a number of executives (mostly those who had never used the reserved spaces) complained to the HR manager about the union president’s “intrusion.”

The HR manager asked the new union president why he had parked his car in the area reserved for visitors and company executives. “I’m an executive,” the union leader replied.

Please take a few minutes to respond briefly to the following questions regarding the brewing conflict between the HR manager and the new union president.

1. If you were the HR manager, what, if anything, would you say to the union leader’s statement, “I’m an executive”?

_____________________________________________

_____________________________________________

_____________________________________________

2. If you were the HR manager, what actions would you take in response to the union leader’s “intrusion”?

_____________________________________________

_____________________________________________

_____________________________________________

3. If you were the HR manager, what actions would you not say and not do in response to the union leader’s “intrusion”?

_____________________________________________

_____________________________________________

_____________________________________________

If your orientation is primarily forcing, your responses to the questions in Exercise 5–2 were probably similar to the following:

1. If I were the HR manager, I’d say, “I don’t think so. You’re an employee of this company, not an executive. If you think we’re going to recognize the union president as a company executive, then you had better think again. Move your car out of that space now. That’s that.”

2. If the union president refused to move his car immediately, I’d fire him on the spot for insubordination. If he didn’t move the car after I gave him a direct order, I’d have it towed away.

3. I wouldn’t say or do anything that demonstrated weakness on my part. The new union president is testing for weakness, and the company must be firm and uncompromising. The old line “If you give them an inch, they’ll take a mile” applies here. Specifically, I wouldn’t do or say anything that recognizes the union president as a company executive who has the right to park in the reserved spaces.

These responses are consistent with a forcing orientation. A forcing negotiator takes firm positions, communicates these positions to the other side in an unequivocal manner, and takes whatever actions are necessary to win the negotiating contest. This type of negotiator has to win everything at the expense of the other party, who’s not permitted to win anything. But if the other side also has a forcing orientation and the power to back it up, the negotiations could evolve into a drawn-out and mutually destructive conflict. For example, let’s say the new union president responded to the HR manager’s threats and demands by saying, “Go ahead and fire me! I’m not moving that car! But get ready for a wildcat strike. This union’s not going to sit on its hands if you fire me. If you want a fight, you’re going to get one. And it will be a lot bigger than you think!” By countering in this way, the union president has escalated the conflict to a much higher and more damaging level. Both sides have taken firm positions and by doing so have moved closer to a major conflict between management and labor.

But let’s assume you have a compromising approach. The following responses to the three questions demonstrate that orientation:

1. If I were the HR manager, I’d say, “Hey, I know you’re the union president. I was planning to get together with you soon to find out how we see the world. But those parking spaces out front are reserved for the top guys. Heck, I don’t even park in them. If you want, I could reserve a space for you in the parking lot close to the door. That way you get the recognition and I keep the top people around here happy. What do you say?”

2. I wouldn’t take any direct or rash actions, such as towing the union president’s car away. I’d try to work out some deal with him and keep things low-key and out of view of both the top brass and the employees. There’s no point in blowing this episode way out of proportion.

3. I wouldn’t make any threats or respond angrily. But I wouldn’t give away the ship, either. I’d also be careful not to say or do anything that would give the union president the idea that he has a right to park in the reserved spaces.

These reactions are consistent with a compromising stance. A negotiator who compromises is always searching for common ground, an agreement both sides can accept, even if reluctantly. This style assumes that both sides need partial victories in order to eliminate the conflict. In our case, the compromise was quite simple: The union president gets a reserved parking space but not one of the highly visible spaces in front of the factory. If the union president accepts this arrangement, the potentially destructive conflict will be resolved.

Of course, the union president could complicate matters by demanding more concessions. He could say, “That’s not a bad idea. A reserved space for me near the parking lot entrance to the plant. Good deal. But I also want reserved spaces for my union officers, the grievance committee, and my shop stewards. Let’s see. That’s twenty reserved spaces. If you give them to me—right in front of the parking space door—I’ll be happy. And then I’ll keep away from the parking spots out front.”

This response creates a real problem for the HR manager. Although the new union president is willing to compromise, he’s raised the stakes. So the HR manager’s proposed solution to the problem becomes only one proposal in what could become an extended series of proposals and counterproposals. If the HR manager can give only one reserved space to the union, she’s in a difficult position. She has no room for maneuvering because her first proposal is her final one. Clearly, this might cause the negotiations to break down into a protracted conflict.

Finally, let’s assume you prefer collaboration to the other two approaches. You would have answered the three questions in the following way:

1. I wouldn’t respond to the union president with anything that would set him off. He’s obviously trying to show off and get me angry. The last thing I’d do would be to give him what he wants. Instead, I’d thank him for the information and invite him back to my office. There I would explain the dilemma he had put me and the company in; then I would say, “Tim, how would you propose that I deal with this dilemma?”

2. Again, I wouldn’t act hastily—like demanding he move his car or having it towed away. The new union president is probably just testing me and the company. Anyway, there’s a good chance he’d stop parking there if we ignored it. He’s acting a little bit like a child; he wants attention, and if I refuse to give it to him, he might give up. If this didn’t work, I would ask him to lunch to discuss the problem—giving him every opportunity to tell his side of the story.

3. I wouldn’t say or do anything to escalate this minor annoyance into a fullblown crisis. The issue is too small to make a big deal over it. On the other hand, I wouldn’t give him my permission or blessing to park in the reserved spaces. That would be going too far. Basically, I would ignore him for a while and hope that this particular issue just went away. But if it didn’t, I’d have an honest, direct conversation with him and find out what he really wants. I suspect the parking issue is just the tip of the iceberg.

These responses illustrate the collaborating approach. A collaborating style condones neither emotional outbursts nor personal attacks. What these responses suggest is that this negotiator thinks the problem might go away by itself in a short while, but if it doesn’t, then it would be time to do some creative problem solving with the union president.

PRINCIPLED NEGOTIATION

Recall Gordon F. Shea’s definition of negotiation in the beginning of this chapter: “Creative negotiation is a process whereby two or more parties meet and, through artful discussion and imagination, confront a problem and arrive at an innovative solution that best meets the needs of all parties and secures their commitment to fulfilling the agreement reached.” This definition clearly captures the essence of the collaborating approach toward conflict resolution.

As introduced in Chapter 1, Roger Fisher, William Ury, and Bruce Patton also recommend that negotiators use the collaborating approach. Instead of creative negotiation, however, Fisher, Ury, and Patton refer to their ideal orientation as negotiation on merits, or principled negotiation. Fisher, Ury, and Patton give this description of principled negotiation:

[It is] neither hard nor soft, but rather both hard and soft. The method of principled negotiation developed at the Harvard Negotiation Project is to decide issues on their merits rather than through a haggling process focused on what each side says it will and won’t do. It suggests that you look for mutual gains wherever possible, and that where your interests conflict, you should insist that the result be based on some fair standards independent of the will of either side. The method of principled negotiation is hard on the merits, soft on the people. It employs no tricks and no posturing. Principled negotiation shows you how to obtain what you are entitled to and still be decent. It enables you to be fair while protecting you against those who would take advantage of your fairness (Fisher et al. 1991, xii).

Let us examine in further detail four of the seven major tenets of principled negotiation that we presented in Chapter 1—the four that Fisher, Ury, and Patton emphasize the most (Fisher et al. 1991, 10–11):

1. People: Separate the people from the problem.

2. Interests: Focus on interests, not on positions.

3. Options: Generate a variety of possibilities before deciding what to do.

4. Criteria: Insist that the result be based on some objective standard.

People

According to Fisher, Ury, and Patton, negotiators frequently confuse the people on the other side of the problem with the problem itself. But those people are generally not the problem. Usually, the problem is rooted in the lack of agreement between the two sides.

We’ve already touched upon this issue in earlier chapters. We’ve mentioned, for example, that structural conflict can develop into strong interpersonal conflict as the participants become more emotionally involved in the struggle. Negotiators using the collaborating approach try to keep a tight rein on their emotions and not lose control of them. Of course, this is much easier said than done. Conflicts can be volatile—anger can come easily. Nevertheless, the best negotiators control their responses no matter how heated the negotiations become.

How can you, as a negotiator, remain emotionally calm, particularly if the other side is doing everything in its power to provoke you? Continuing with our case analysis, consider these remarks by our collaborating HR manager as she deals with the parking controversy:

Sure, I can feel myself getting angry at times. Some people do all they can to knock you off balance, to make you mad. But I’ve learned a couple of tricks. Whenever I get too personally involved, I don’t say very much. I become quiet. I even lower my voice and slow my speech. I also try to ask more questions and make fewer remarks. That way I keep my cool and stop myself from saying something I might regret. It’s hard to do, but sometimes it’s the only way I can stay calm.

The HR manager has developed a few techniques to help herself remain emotionally detached. She speaks less, talks slower, lowers her voice, and asks more questions. In this way, she can pull herself away from the emotional quagmire the other negotiator is pushing her toward. She knows that losing emotional control will harm the negotiations and intensify the conflict. Thus, she avoids contributing to an escalation of the conflict.

But suppose the other side is really trying to get you mad and the techniques used by the HR manager don’t work? How would a collaborating negotiator proceed then? Let’s assume the HR manager and the new union president are having a private discussion in the HR manager’s office. Consider this exchange:

UNION PRESIDENT: |

Jean, you know what’s wrong with this company, but you’re just too scared of the big guys to admit it. The head honcho doesn’t care about the workers. He’s got to have all the reserved parking places for himself and his clique. If you’d open your eyes, you’d admit that I’m right. What are you? A lackey and a coward!? |

HR MANAGER: |

Tim, I’ve listened to your speeches and given you every courtesy. I’ve been attentive and polite. But I have to draw the line someplace. I don’t like words like head honcho, lackey, and coward. Those are fighting words and you know it. How would you like it if I called you and your union members idiots or parasites? |

UNION PRESIDENT: |

Well, I wouldn’t like it. I’d probably walk out of here. |

HR MANAGER: |

That’s what I would do, too. But let’s keep this discussion at a high level and refrain from trying to get each other mad. How about it? |

UNION PRESIDENT: |

All right. You’ve got a point. Let’s get back to the real problems I’m having with Masoon Company. |

HR MANAGER: |

Good idea, Tim. |

Notice that the HR manager did not just ignore the loaded words used by the union president. She voiced her displeasure, but she did it in a calm, even manner. By asking the union president how he and his members would respond to name-calling, the HR manager made him understand how his statements affected the negotiating process. This lesson was accepted by the union president, and the negotiations continued at a less personal level.

Separating the people from the problem is necessary in order to remain emotionally detached during the negotiating process. This is how collaborating negotiators stay calm. They refuse to be drawn into an angry exchange of insults, even if the other side instigates it. Instead, they will do everything they can to elevate the negotiations to a courteous, civilized plane. In this way, the negotiations continue to focus on the issues, not on the people discussing them.

As discussed in this chapter, managers who are good at conflict resolution do not confuse the people involved in a dispute with the issue that is being disputed. These managers are hard on the merits of the argument each side presents, but soft on those doing the presenting. However, it is not easy to control one’s emotions when dealing with people who are quick to raise their voices, quick to use abusive language, quick to become emotional or angry. Tool 5–1 lays out guidelines for you to follow when dealing with difficult people such as Tim, the union president.

Conflict Resolution Tool Box

Conflict Resolution Tool Box

Tool 5–1 Keeping Your Poise When Negotiating with Difficult People

Conflict resolution expert William Ury has developed a solid set of guidelines for dealing with difficult people (such as Tim, the new union president, in this chapter’s case study). These guidelines have grown out of years of studying the problem and years of being in the trenches as a negotiator. Ury advises that when you are met with hostility:

1. Don’t react emotionally! Rather, try

a. Saying nothing for a period, while letting your opponent vent his or her emotions.

b. Taking a time-out (“We’ve been talking for some time now. Before continuing, let me suggest a quick coffee break.” Or “That’s a good question. Let me find out and get back to you right away.”) It helps to have some ready-made excuses.

c. Maintaining an awareness of your “hot buttons.” That is, if you know certain things bother you and your opponent hits on one of these, you can deflect your natural (angry) response because you were already prepared for the possibility that this button might be pushed.

2. Step to their side. By empathizing—putting yourself in your opponent’s shoes—you can diffuse a lot of their hostility. Some actions that will help you do this include

a. Listening actively (see Tool 4–6), hearing your opponent out.

b. Acknowledging their point; every human being has a deep need for recognition. You may be reluctant to do this if you disagree strongly with what has been said. However, by satisfying this need, you create a climate for agreement.

c. Acknowledging your opponent’s feelings, and if he or she sees you as the cause of his or her anger, be quick to say “I’m sorry.” Your apology need not be an act of shouldering the lion’s share of blame. Even if your opponent is primarily responsible for the mess you are in, consider apologizing for your share. Your bold gesture can set in motion a process of reconciliation in which he or she apologizes for his or her share. In short, until you diffuse his or her emotions, your reasonable arguments will fall on deaf ears.

d. Agreeing wherever you can. “The key word in agreement is yes. Yes is a magic word, a powerful tool for disarming your opponent. Look for occasions when you can say yes to the other side without making a concession. “Yes, you have a point there.” “Yes, I agree with you.” Say yes as often as possible. In this vein, substitute the word yes for the hackles-raising word but.

e. Acknowledging the authority and competence of your adversary. Be quick to say something like “I thought your presentation at the meeting was first-rate.”

Adapted from William Ury, Getting Past No: Negotiating with Difficult People, Bantam 1991, pp. 31, 40–43, 51.

Interests

Fisher, Ury, and Patton recommend that negotiators concentrate on interests, not on positions. What is the difference between the two? A position is something you request or demand; an interest is what caused you to request or demand. Fisher, Ury, and Patton offer the following example to illustrate the difference between an interest and a position:

Consider the story of two men quarreling in a library. One wants the window open and the other wants it closed. They bicker back and forth about how much to leave it open: a crack, halfway, three-quarters of the way. No solution satisfies them both.

Enter the librarian. She asks one why he wants the window open: “To get some fresh air.” She asks the other why he wants it closed: “To avoid the draft.” After thinking a minute, she opens wide a window in the next room, bringing in fresh air without a draft.

This story is typical of many negotiations. Since the parties’ problem appears to be a conflict of positions, they naturally tend to think and talk about position—and in the process often reach an impasse. The librarian could not have invented the solution she did if she had focused only on the two men’s stated positions of wanting the window open or closed. Instead, she looked to their underlying interests of fresh air and no draft. This difference between positions and interests is crucial. (Fisher et al. 1991, 40)

Returning to our case, the positions of labor and management are quite clear. The union president wants to park his car in the spaces reserved for visitors and executives of Masoon Company; the company, represented by the HR manager, does not want him to park there. This presents us with an either/or situation. Either the union president wins or the company does. Because both sides have taken such hard stands, an innovative solution does not seem possible.

But let’s go beyond these stated positions. Let’s uncover the interests behind them. When the HR manager asked herself why she didn’t want the union president to park in the reserved spaces, she came to the following conclusion:

I suppose part of it is pride. We’re proud of our company and want to honor those who serve it well—the president and the three vice presidents, for example. But that’s probably not the only reason. I suppose I’m interested in looking good to my boss. If I can’t control the union, I appear weak and ineffectual. Also, I’m not sure what the new union president is trying to accomplish. Is he testing the company? Is this merely the first skirmish in a new war with the union? If he’s looking for a fight, I probably should get involved as early as possible. Giving in on the parking issue would just postpone the battle until a potentially bigger issue comes along.

From this answer, we can observe the more substantial interests underlying the HR manager’s stated position. She thinks the top executives should receive recognition, she wants to impress his superiors, and she wants to meet the union challenge as soon as possible. It may be possible to satisfy most if not all of these interests and still allow the union president to park in the reserved spaces. Let’s follow the HR manager as she pursues another line of thinking:

If this new union president is really militant, the last thing he’d want to be called is a company executive. The other members would see this as selling out to the enemy. And it would really weaken his credibility. So maybe it would be a good strategic move to recognize him as a company executive and let him park in those special spaces. And to formally recognize his new rank, I’ll send out a memo to all employees stating that Tim, unlike the old union president, wants to be recognized as a company executive. That might take the bluster out of him and make him more reasonable.

This thinking may result in the HR manager achieving her basic interests. The company’s president might view this as a clever way to deal with the union, and the new union president might decide that being viewed as a company executive might not be politically wise and decide to park his car in the lot.

Now let’s try to uncover the interests underlying the union president’s position. Here’s what he has to say:

I parked in the reserved area because I wanted to get the company’s attention to show them that a new guy is taking over who won’t be walked on. I thought this was a good way to get their attention and respect. It will also show the union membership that I mean business and I’m tough—not like the old union officials. They were too chummy with management.

Clearly, the new union president is trying to establish himself as a tough, capable official, in the eyes of both the company and the union membership. He thinks one way to do this is to park in the reserved spaces. But if this act makes him look like a company man, he’ll probably refuse to park his car in a reserved space.

Note that the interests of the HR manager and the union president are not totally conflicting. Both might be able to achieve their objectives: recognition for the union president and a strong stand against union abuses for the HR manager. We will explore innovative options in the next section.

But before moving on, a key point to understand is that interests and positions are not usually identical. Behind stated positions are deeper and more basic interests. By asking yourself and the other side what your stated positions represent, the real reasons behind them can be uncovered. Once you know why you and the other side take specific positions, you can create an agreement that will satisfy the basic interests of both sides and provide each with a real victory. This is critical to the collaborating approach to negotiation.

Options

Fisher, Ury, and Patton relate a classic tale about two sisters and an orange (Fisher et al. 1991, 56–57). Both sisters wanted the orange, and each demanded that the other one hand it over. Finally, after much bickering, they agreed to split it in half. The first sister took her half, ate the fruit, and tossed out the peel; the second sister used the peel from her half to bake a cake and discarded the fruit. They both won something—half an orange—but lost the opportunity to double what they really needed, either the fruit or the peel. Too frequently, negotiators work out compromises that give one side half the fruit and the other side half the peel. They miss the opportunity to maximize the gains for both sides. In their haste to split the difference, both sides get only a fraction of what they could have obtained if they had taken the time to think through the various options available to them—options that could have led to a more satisfying resolution of the more fundamental issues dividing them. Collaborating negotiators should generate a variety of options before agreeing to a particular compromise position. To help you understand this concept, complete Exercise 5–3.

![]() Exercise 5–3

Exercise 5–3

Reread Exhibit 5–4, “The Case of the Reserved Parking Spaces.” Then try to think of five possible options that might resolve the conflict satisfactorily. Be creative.

Option 1______________________________________

_____________________________________________

Option 2______________________________________

_____________________________________________

Option 3______________________________________

_____________________________________________

Option 4______________________________________

_____________________________________________

Option 5______________________________________

Although we don’t know which options you’ve selected in completing Exercise 5–3, we’ve come up with five of our own. Compare yours to ours:

• Option 1: Inform the town’s police department that a noncompany executive is parking in the reserved spaces. After all, the town created this parking area. Let the police talk to the union president. In this way, the town, not the company, will be the bad guy.

• Option 2: Eliminate reserved parking areas. They’re not helpful in establishing friendly employee-employer relationships. They create distinctions that are not useful, particularly if a militant union leadership exists.

• Option 3: Reserve an area in the parking lot for union officials. But make sure the union, not the company, will be responsible for enforcing the parking restrictions there.

• Option 4: See if the union president and the HR manager can select a fair and impartial third party to decide the appropriateness of the union president parking in spaces reserved for visitors and company executives. A faculty member from a local university might be a good choice.

• Option 5: Tell the union president he can park in the reserved places out front, but only if he buys a new car. Executives must project a high-level image to visitors and neighbors of Masoon Company and a ten-year-old car detracts from this.

Some of these options may be too unusual for one or both sides to consider seriously. But the point of generating a number of options is to force yourself to think creatively. If neither side proposes imaginative alternatives to a safe but unsatisfying compromise position, both sides may lose out, like the two sisters with the orange.

Some people object to option generation because they fear that the other side may not cooperate—for example, they recognize that some adversaries aren’t concerned about the other side’s interests or whether the other side’s problems are solved in the negotiating process. However, collaborating negotiators will overcome such fears. They realize that an imaginative solution satisfying both sides is the ultimate aim of their negotiating efforts. Thus, working with the other side to arrive at creative solutions that meet underlying interests is the real goal of the collaborating negotiator, not total victory for one side or the other. As both sides generate options, the real interests of each can be uncovered and examined closely. When a particular option that benefits both parties is arrived at, the conflict can be resolved and the interpersonal relationship between the negotiators can thereby be strengthened. Tool 5–2 details several recommendations for getting principled negotiation up and going with a feisty opponent who is reluctant to play the options game.

Conflict Resolution Tool Box

Conflict Resolution Tool Box

Tool 5–2 Generating Options When Negotiating with Difficult People

As discussed in this chapter, managers skilled at conflict resolution are able to generate options to resolve disputes in such a way that the legitimate interests of both sides are met. William Ury advises that when you find yourself involved with a disputant who seems unwilling or unable to approach a dispute creatively, then:

1. Ask problem-solving questions. Making assertions can arouse the disputant’s resistance. The better approach is to ask questions:

a. Ask why, and do so softly. Indirect questions are often better than direct ones: “I’m not sure that I understand why you want that,” “Help me to see why this is important to you,” or “You seem to feel pretty strongly about this—I’d be interested in understanding why.” It helps to preface your question with an acknowledgment: “I hear what you’re saying; I’m sure the company policy has a good purpose—could you please explain it to me?”

b. Ask why not: “Why not do it this way?” “What would be wrong with this approach?”

c. Ask what if. Suppose your customer announces “That’s all the money we have in the budget to pay for this consulting project. We can’t pay a penny more!” Ask the customer “What if we were to stretch out the project so that the excess could go into next year’s budget?” or “What if we were to reduce the magnitude of the project to fit within your budget constraints?” or “What if we can help you show your boss how the benefits to your company justify asking for a budget increase?” If you can get the customer to address any one of these questions, you will have succeeded in changing the game. Suddenly he or she is exploring options with you.

d. Ask the disputant’s advice. Another way to engage the person in a discussion of options is to ask for his or her advice. It is probably the last thing he or she expects you to do. Ask “What would you suggest that I do?” “What would you do if you were in my shoes?”

2. Don’t let the disputant or yourself assume a fixed “pie.” More for you does not necessarily mean less for the other party, or vice versa. To expand the pie, use the following tactics:

a. Look for low-cost, high-benefit trades. That is, identify items you could give the disputant that are of high benefit to him or her but low cost to you. Similarly, seek items that are of high benefit to you but low cost to him or her.

b. Use an if-then formula. You want more, the disputant wants to give you less. Base your getting more on his or her getting more, too. For example, one of Ury’s colleagues could not convince the editor of his textbook that he should get a royalty higher than the current industry standard. The colleague broke the impasse by offering the editor this deal: For the first 3,000 copies of the book sold, he would receive the standard royalty; however, for every copy sold thereafter, he would make an additional 3 percent. The editor was risking little because her publishing company was going to make money either way (though more if more than 3,000 copies were sold, even with the slightly higher author’s royalty).

3. Show how new options can help the disputant save face. Ury stresses this tenet more than any other: Face-saving is at the core of the negotiation process. Everyone likes to feel good about himself or herself and have the respect of coworkers and associates. Losing a conflict hurts in both of these areas. Let the disputant save face by using the following strategies:

a. Show the disputant how circumstances have changed. Admit that originally he or she was right, but explain how circumstances have now changed—thereby providing an acceptable excuse for giving in.

b. Ask for a third-party recommendation. A time-honored method of face-saving is to call in a third party—a mediator, an independent expert, a mutual boss, or a friend. A proposal that is unacceptable coming from you may be acceptable if it comes from a third party.

c. Point to a standard of fairness. This allows the disputant to change his or her mind without feeling he or she is backing down—rather, the person is simply deferring to, say, the market price (or legal precedent, and so forth. See the section entitled “Criteria” in this chapter.)

Criteria

Consider the following exchange between the union president and the HR manager:

HR MANAGER: |

Tim, you said you’re having problems with Masoon Company. Is that why you parked in the spaces reserved for visitors and executives? |

UNION PRESIDENT: |

Jean, I have a lot of problems with this company, and I wanted to make a point. The top brass get all the privileges, and the workers get nothing. The point I’m trying to make is that I am an executive of this company because I represent the employees. And as an executive, I have a right to park in the executive area and a right to the same respect the other executives get. |

HR MANAGER: |

I hear what you’re saying. But I can’t buy it. You’re an executive of the union, not the company. The board of directors of Masoon Company appoints the top managers. You weren’t appointed by them. You were elected by the production and maintenance people. You’re a union executive, not a company executive. |

UNION PRESIDENT: |

I guess we don’t agree at all on this one. |

HR MANAGER: |

You’re right, Tim, we don’t. And I don’t want to have a big fight with you on this issue. |

UNION PRESIDENT: |

Neither do I. But I can’t back down, Jean. I’ll look weak to my membership. |

HR MANAGER: |

And I can’t back down, either. I’ll look weak to the president. |

UNION PRESIDENT: |

Well, how do we handle it? |

HR MANAGER: |

Let’s think about it for a day. Maybe we can find somebody or some objective standard to get us out of this mess. |

Negotiating results should be based on some objective standard or procedure, not determined by who has the most power. Reason and objectivity are more acceptable and less damaging than the relative power and will of the negotiators. As Fisher, Ury, and Patton emphasize, we are not always going to get our way in life. None of us can win every battle. When we do lose, however, it is easier to accept if we see “justice” in the outcome. You will also win more battles amicably if you can show your opponent that the outcome you desire is based on some or all of the criteria of a fair standard.

Although the standard emphasized in this course is organizational performance, Fisher, Ury, and Patton offer many others you might use when you’re in a pinch—including market value, legal decisions, precedent, scientific judgment, professional standards, efficiency, and costs (Fisher et al. 1991).

Of course, the standards must be applied judiciously. For example, if an insurance company and a car owner disagreed about the settlement the insurance company should make to the car owner for damages to his car, the market value of the car would be a more useful guideline than moral standards or tradition. But a disagreement among high school students about where to hold this year’s prom might best be resolved by using tradition as the key criterion.

Objective procedures should be considered as both an aid and a possible substitute for objective standards. For example, taking turns, drawing lots, and sharing decision making are all objective procedures that can be used by collaborating negotiators to resolve conflict. Fisher, Ury, and Patton note, for example, how two children divide a piece of cake. One cuts and the other chooses. Neither can legitimately complain about an unfair decision.

How can objective criteria and procedures be used in the parking conflict? Although we can suggest many possible variations, consider the following approach agreed to by both the HR manager and the union president: The two individuals decided that a protracted squabble on this issue wouldn’t help either of them. The company didn’t want to upset the union membership, and the union president didn’t want the company to use its authority and influence to have the town tow his car away. So both parties agreed to allow the mayor to make a final, binding decision. The company found this acceptable because the mayor had been helpful in the company’s relocation to the town. The union president agreed to the procedure because the mayor had always been viewed as pro-labor. The mayor suggested that the company allow the union president to park his car in the reserved area for one month. When that month was up, the union president would again park in the parking lot in back of the factory. In this way, the union president would make his point and have a small victory, but the company would eventually have all rights to the reserved area. In addition, the union president would have to promise never to repeat this action.

This solution to the conflict was both innovative and valuable to both sides. The union president got what he wanted—the attention and respect of the company. And the HR manager was also satisfied. She resolved the conflict without appearing weak to the company president or the union. Through the use of an objective procedure—having a respected outsider decide the issue—the two parties were able to arrive at a mutually acceptable solution to the dispute.

In this chapter, we have defined the meaning of negotiation and described in depth how negotiations can be used to resolve conflict. Negotiation was defined as “conferring or discussing with another person or persons with a view toward reaching agreement.” It is a basic method of getting what you want or need from other people. It is an open approach to conflict resolution.

There are five basic approaches to conflict resolution: forcing, compromising, avoiding, accommodating, and collaborating. Many managers believe that they personally approach negotiations with a collaborative, willing-to-negotiate orientation but feel that the other side’s orientation tends to be forcing. The forcing, compromising, and collaborating approaches were examined in detail.

A forcing approach is one in which one or both sides attempt to satisfy their own needs regardless of the impact on the other side. A compromising approach is one in which both sides gain and lose in order to resolve the conflict. A collaborating approach is an attempt by one or both parties to fully satisfy the needs of both parties. There is no one correct approach; conflict resolvers need to be aware of the advantages and disadvantages of each.

The collaborating approach to negotiations was recommended as being the most valuable approach to conflict resolution. While there are a number of ways to develop this approach, the method suggested by Fisher, Ury, and Patton, principled negotiation, was proposed as the most comprehensive. Four elements of their approach include (1) separating the people from the problem; (2) focusing on interests, not positions; (3) generating a variety of possibilities before deciding what to do; and (4) insisting that the result be based on some objective standard.

One tactic for separating the people from the problem is not reacting emotionally to the hostility displayed by an adversary. This can be achieved by saying nothing for a period, while letting the other party vent his or her emotions. It can also be done by taking a time-out and by maintaining an awareness of one’s “hot buttons.”

Another tactic to help you separate the people from the problem is to “step to their side.” By empathizing—putting yourself in the other party’s shoes—you can diffuse a lot of their hostility. Some actions that will help you do this include (1) listening actively; (2) acknowledging the other party’s point; (3) acknowledging the other party’s feelings, and if he or she sees you as the cause of his or her anger, being quick to say “I’m sorry”; (4) agreeing wherever you can; and (5) acknowledging the authority and competence of the other party.

One tactic for generating a variety of possibilities with hostile parties who don’t want to play this game is to ask problem-solving questions: (1) Ask why, and do so softly; (2) ask why not; (c) ask what if; and (d) ask for the other party’s advice.

Another tactic for generating possibilities is not letting you or the other party assume a fixed “pie.” One strategy for expanding the pie is to look for low-cost, high-benefit trades. That is, identify items you could give the other party that are of high benefit to him or her but low cost to you; similarly, seek items that are of high benefit to you but low cost to him or her. Another strategy for expanding the pie is to use an if-then formula. You want more; the other party wants to give you less. Base your getting more on his or her getting more, too.

A third tactic for generating possibilities is to show how new options can help the other party save face. One way to do this is to show him or her how circumstances have changed. A second means is to ask for a third-party recommendation. Finally, try pointing to a standard of fairness. All of these approaches allow the other person to change his or her mind without feeling he or she is backing down.

1. Key to the definition of negotiation is the idea that it requires: |

1. (c) |

(a) compromise. |

|

(b) accommodation. |

|

(c) innovation. |

|

(d) a degree of force. |

|

2. The “collaborating” HR manager controlled her emotions when interacting with the hostile union president by: |

2. (d) |

(a) speaking less. |

|

(b) lowering her voice. |

|

(c) asking questions. |

|

(d) all of the above. |

|

3. ___________occurs when both sides gain and lose in order to resolve a conflict. |

3. (d) |

(a) Forcing |

|

(b) Avoiding |

|

(c) Accommodating |

|

(d) Compromising |

|

4. The disadvantage of forcing is that: |

4. (d) |

(a) negotiation can easily lead to a stalemate. (b) the winner can make a bitter enemy out of the loser. |

|

(c) both sides have to give in. |

|

(d) a and b. |

|

5. When practicing principled negotiation, one must be sure to: |

5. (b) |

(a) keep the people and the problem together. |

|

(b) insist the result be based on some objective standard. |

|

(c) focus on positions, not interests. |

|

(d) come up with a single option for handling the situation. |