2

Recognizing Types of Conflict

Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter, you should be able to:

• Explain why conflict resolution is so important to a manager.

• Identify the three basic types of conflict.

• Describe the six root causes of structural conflict.

• Define interpersonal conflict, and give at least one example of how structural conflict can be transformed into interpersonal conflict.

• Describe how potentially destructive conflict can be transformed into constructive conflict by applying one or more of the seven basic tenets of principled negotiation.

INTRODUCTION

In all organizational situations, managers must have an understanding of what they are dealing with before implementing solutions. Too many managers, in their haste to resolve a conflict, apply the right solution to the wrong problem. In this chapter, we’ll examine the types of conflict and the role managers should play in their resolution. This approach should help managers apply the right solution to the right problem. First, however, we’ll explore the manager’s job and the part conflict plays in it.

THE MANAGER’S JOB

Many of you have read about or taken a course in management practices, and you probably have a good, solid understanding of the managerial role; but let’s see whether you remember the fundamentals.

Think about how you have come to understand the managerial role. Before you read any further, write down a simple definition of management. Take no more than a couple of minutes to do this.

_____________________________________________

_____________________________________________

_____________________________________________

_____________________________________________

_____________________________________________

_____________________________________________

You have probably come up with a valid, useful definition of management, such as the following: “Management is getting things done through other people.” This is a correct, though simplistic, definition of management. Consider this more elaborate definition: “Management is a process by which one or more persons coordinate the activities of others in order to efficiently achieve results not achievable by any one person acting alone.”

Managers attempt to achieve results efficiently through subordinates. Thus, like all professions, managers are oriented toward results and efficiency, but they use other people to achieve these goals.

You may be wondering how this discussion relates to conflict and conflict resolution. Recall that in Chapter 1, great importance was placed on organizational performance. It was stated that conflict and conflict resolution should be evaluated in terms of their effect on organizational performance. In the process of efficiently achieving results through others, managers must deal with conflict and develop useful ways to resolve it, making conflict resolution a significant aspect of the management process.

What activities are included in the managerial process? Henri Fayol, a French industrialist, developed what is still the most popular list of managerial functions (Fayol 1949). Fayol stated that managers plan, organize, command, coordinate, and control. Most current management writers recompose Fayol’s list to include planning, organizing, controlling, and directing.

Henry Mintzberg, a leading management writer, has identified three key elements, or activities, performed in the managing process: dealing with people, handling and using information, and making decisions (Mintzberg 1973). He discovered that most successful managers are much less scientific and systematic than is often assumed. He demonstrated that most managers work at an unrelenting pace; that their activities are characterized by brevity, variety, and discontinuity; and that they are strongly oriented toward action and tend to steer away from reflective activities.

Mintzberg also identified a number of specific activities that managers perform in order to deal with conflict. In particular, he discovered that managers spend a considerable amount of time handling disturbances, allocating resources, and negotiating among conflicting parties and viewpoints. Thus, conflict and its resolution consume a significant portion of the average manager’s time and energy. It has been estimated that managers commonly spend 20 percent or more of their time resolving conflict (Thomas and Schmidt 1976; Watson and Hoffman 1996). They also spend a lot of time trying to avoid conflict (see Chapter 6). In short, because managers deal with conflict so often, conflict resolution is an important topic for them to study. Indeed, scientific studies of successful and unsuccessful managers find that most successful managers are keenly oriented toward conflict management (Luthans et al. 1985).

CATEGORIZING CONFLICT

As stated, managers must understand what kind of conflict they are facing before proposing solutions to it. There are a number of ways to break down conflict situations into specific categories. To a certain extent, we have already begun to do this. In Chapter 1, we distinguished between conflict caused by structural conditions and conflict originating from interpersonal factors. This distinction is useful in finding effective approaches to resolving conflict. As we shall see, structural conflict is resolved best through structural resolution methods, while interpersonal conflict demands interpersonal solutions.

It is also possible to categorize conflict based on the degree to which a manager is involved in it and the manager’s relationship to the conflicting parties. This is where we will now turn our attention—using these two factors to distinguish among the different types of conflict.

WHERE THE MANAGER SITS

Consider the following two incidents. In the first incident, Janine Whales, a production supervisor, is walking through her work area when she hears an argument in process. Frank and Bill, two of her employees, are angrily discussing an overtime opportunity. As Janine tunes in to the discussion, she hears this interchange:

FRANK: |

That’s unfair! I always get the short end of the stick on overtime. Every time it rains, you get scheduled for overtime. Every time it’s nice outside, I get the overtime. |

BILL: |

I told you before, Frank, I’m willing to take all the OT I can get. If you want to go home today and bask in the sun, go ahead. I’ll be happy to work your overtime—I need the money. |

FRANK: |

That means I’ll have to work the next OT, right? |

BILL: |

Wrong. I’m just offering to work your OT. I’m not giving up mine. I’ll get my scheduled overtime next week—rain or shine. I’m just trying to do you a favor, that’s all. |

Some favor. I either give up my OT, or I work it on the only nice afternoon this week. Some choice you’re giving me. | |

BILL: |

Fair’s fair. The weather’s a matter of luck. And I’ve been lucky and you haven’t. That’s all. |

Now examine the second incident. Janine Whales is approached by Frank, and the following discussion takes place:

FRANK: |

Janine, I have a problem about my overtime. In the last month and a half, I seem to have gotten my OT on every nice afternoon and Saturday we’ve had. You know how I love the beach. This overtime has ruined my summer. |

JANINE: |

What do you want me to do about it, Frank? Change the weather? |

FRANK: |

I’m serious, Janine. This is really getting me down. Maybe you could change the way OT is handed out—at least in the summer. I know you work out the OT by turns. Everybody gets a chance, and if you turn it down, your name goes to the bottom of the list, unless you change times with somebody else. |

JANINE: |

Yes. And I think most of our employees want it that way. |

FRANK: |

That’s probably true. But here’s an idea. Why can’t a guy turn it down and still have his name on the top of the list for the next time. If he turns it down twice in a row, then his name goes to the bottom. That’s only a small change. |

JANINE: |

I don’t know. I don’t want to complicate things around here. |

FRANK: |

This won’t complicate anything. Give me a break. Bend the policy a little. I’m sure most of the others would go along with it. It’ll give us all a bit more freedom. |

JANINE: |

I’m going to have to say no on this, Frank. If you can’t get somebody to switch with you, that’s the way the old cookie crumbles. I’m not going to get involved. It’ll only make matters worse. Sorry, Frank. |

FRANK: |

Thanks for nothing, Janine. Everybody seems to be ganging up on me. I thought you’d at least help. But even you won’t give me a break. I guess I shouldn’t expect anything from anybody. |

What is the fundamental difference between incident one and incident two? Both involve a production worker concerned about working overtime in nice weather. In both cases, the worker did not get what he wanted. So what is the difference? The key difference is the involvement of the manager in the dispute. In the first incident, the manager was an observer of the conflict episode—Janine Whales overheard an argument between two of her employees regarding overtime scheduling. In the second incident, Janine was a direct participant in the conflict. By refusing to modify the overtime policy, she consciously interfered in Frank’s attempt to increase his chances of not working overtime in nice weather.

Let’s look at one more scenario, adding these developments to the discussion between the supervisor and her employee:

JANINE: |

Don’t get mad at me, Frank! I didn’t say I wouldn’t help you out if I could. I just don’t want to change the policy. Who have you checked with about switching OT assignments? |

FRANK: |

Just Bill. I didn’t have a chance to talk to anybody else. |

I just might have a solution for you, even if it’s only a temporary one. Joe Rotondi can’t work his OT schedule next Tuesday. He’s looking for somebody to switch with him. Why don’t you check with him? | |

FRANK: |

Do you think he’d work tonight? |

JANINE: |

I think so. He really can’t work next Tuesday night. |

FRANK: |

Thanks, Janine. I’ll check with Joe. Sorry I got mad back there. |

JANINE: |

Oh, no hard feelings. Hope it works out with Joe. |

The involvement of the production supervisor is quite different in the third incident. In this case, the supervisor acts as a problem solver, looking for an answer that leaves everybody happy, at least in the short run.

You should be able to detect significant differences in the three incidents. From the manager’s viewpoint, there are major variations in the level of her involvement in the developing conflict. In the first incident, the supervisor was an observer; in the second, she was an active participant; and in the third, she acted as a problem solver and mediator. Thus, one way to determine the type of conflict is to examine the depth and form of managerial involvement.

There is another major variable we should add at this point: authority. Consider the following two incidents. In the first, Janine Whales is approached by her boss, the plant manager, at 2:45 on Friday afternoon. The manager tells Janine that he’s decided to transfer Janine’s best worker to another department for the next two weeks. Even after Janine protests, the plant manager refuses to change his decision. Janine is faced with the prospect of being shorthanded for the next two weeks. In addition, the plant manager is unwilling to reduce Janine’s production goals during this period. Janine is upset but can do nothing about it.

In the second scenario, Janine is approached by another production supervisor at 2:45 on a Friday afternoon. Because of some maintenance problems, this supervisor is far behind in achieving his production goals. He wants to borrow Janine’s best worker for the next two weeks. If Janine cooperates, this supervisor promises to reciprocate in the future. Under production pressure herself, Janine refuses the request. Although she’s sorry she can’t help, she does promise to send over some of her people in the next two weeks if she can spare them. The other supervisor is unhappy but thanks Janine in advance for whatever help she can give.

The difference between these two incidents should be clear. In the first incident, Janine is dealing with her boss. The conflict between Janine and her boss is resolved by a direct order from the manager. In the second incident, two peers are engaged in a conflict. Because neither has the authority to order the other to do anything, the episode ends when Janine refuses the request (see Exhibit 2–1). The other supervisor is unable to convince or force Janine to lend her best worker to the other department for two weeks.

Thus, a second significant variable that’s helpful in distinguishing among conflict types is the status difference between the participants. Because of differences in authority, there is a clear distinction between conflict involving peers and conflict involving superiors and subordinates.

Let’s summarize this discussion and develop the concepts more fully in Exhibit 2–2. This exhibit combines the two major variables we have explored: managerial involvement in the conflict and the organizational relationship of the participants. Examine Exhibit 2–2 carefully before you continue reading.

![]() xhibit 2–1

xhibit 2–1

Definitions of Power, Authority, and Influence

Power is the ability to exercise one’s will over others. For the study of organizations, it can be broken down into two major types: authority and influence.

Authority refers to power that has been institutionalized and is recognized by the people over whom it is exercised. Thus, in your position of manager you may have the power (authority) to set schedules; so did your predecessor, and so will your successor.

Influence refers to the exercise of power through a process of persuasion. Thus, in your position of manager it is unlikely that you can dictate how much one of your subordinates smokes when outside the office. However, if the subordinate respects you and values your opinion in general (not just because of your role as manager), he or she might be willing to cut back on smoking—thereby increasing the chance of staying healthy (and avoiding missing work due to illness).

The Authority of the Manager

Although at first glance Exhibit 2–2 appears complicated, it’s actually fairly easy to comprehend. This is because most managers are intuitively aware of the dynamics summarized in the exhibit. The variable, Organizational Relationship to Manager, is placed on the horizontal axis—are the participants involved in the conflict the manager’s subordinates, peers, or superiors? Clearly, people will behave differently depending on the status of the other parties involved in the conflict.

The authority levels are straightforward. Regardless of your level of involvement in a conflict, you have a lot of power (relatively speaking) if the only other participants are your subordinates, a moderate amount if the other participants are your peers, and a relatively small amount if they’re your superiors.

As shown in Exhibit 2–2, these authority relationships remain constant, even if the Involvement of the Manager (the variable on the vertical axis) in the conflict varies. An observer of a conflict has a low level of involvement; a mediator or problem solver has a medium level of involvement; a judge has a higher level of involvement; and, finally, a direct participant has the highest level of involvement. Note that two cells in this exhibit are empty. This is because managers are unlikely to mediate or judge disputes involving their superiors.

The obvious conclusion to be drawn from Exhibit 2–2 is that it is easier to deal with conflict if you have authority than if you don’t. Therefore, before you jump to any conclusions about a specific conflict situation, you need to assess your degree of authority, as well as that of the other parties. The greater your authority, the more quickly and decisively you’ll be able to act to resolve a conflict. A direct order is an example of a clear and decisive approach to resolving an immediate conflict. However, if you lack sufficient authority, you need to rely on alternative approaches to conflict resolution. That brings us to a consideration of creativity.

Need for Creativity

As your relative authority decreases, your need for cleverness and creativity to resolve the dispute increases. You must persuade the participants in the conflict that your ideas are worth adopting. This demands solutions that help everybody—the kind of solutions that require the most creativity. When dealing with peers and superiors, your need to be creative is essential, unless you are merely an observer. But be prepared! As we have seen in the incidents with the production supervisor, it is relatively easy to be drawn into a conflict and lose your status as an observer.

We’re not saying you shouldn’t be creative in resolving conflict if the amount of authority you have in a conflict situation is relatively high. Being powerful and being creative are not mutually exclusive. In fact, managers who have authority but think of innovative solutions are usually viewed as the best managers (Blau and Meyer 1987). Moreover, it is risky for managers to get too hung up on the question of who’s more powerful. More specifically, if you assume that you are the more powerful, you may become complacent and not think through all the issues that are involved in the conflict. Similarly, if you assume that you are weaker than the other side, there is a risk that you will be discouraged and not work for your best interests.

![]() Think About It

Think About It

Think about a time when you used a creative solution to resolve a conflict. Briefly describe the conflict and your solution. Then do the same regarding a conflict when you simply used power.

_____________________________________________

_____________________________________________

_____________________________________________

_____________________________________________

_____________________________________________

_____________________________________________

Observations and Guidelines for Using Authority and Creativity

We have identified two major variables managers can use to distinguish among the types of conflict situations within their organizations: the organizational relationship of the participants and the degree to which the manager is involved in the conflict. In addition, we have pinpointed two basic tools managers can use in handling and resolving conflict: authority (direct power) and creativity.

The following guidelines should be helpful in analyzing conflict situations and deciding how to approach conflict:

• In conflict involving peers, superiors, or both, managers should usually rely on creativity rather than on authority. Putting the tenets of principled negotiation into practice (see Chapter 1) will yield many creative solutions.

• In conflict involving subordinates only, managers may rely more on authority, even though creativity and principled negotiation may still be the best conflict resolution tools.

• In conflict in which their level of authority is medium to low, managers should avoid a high level of involvement (if they have the option), particularly if the situation involves their superiors.

Most practicing managers have already reached similar conclusions. Nevertheless, it should be helpful for even the most perceptive managers to view them in a more systematic fashion, as presented in Exhibit 2–2 and the three guidelines just provided. Moreover, we assume that many managers will not have been exposed to principled negotiation before this course. Let’s turn to another useful way to categorize conflict situations within organizations.

STRUCTURAL CONFLICT

In Chapter 1, we defined structure as the way the organization is set up and operated—the kinds of jobs and departments and the relationships among them. Why do organizations have structural conflict? More basically, why does the structure of most organizations require different jobs? For an answer, we must examine the concept of division of labor. Read what Adam Smith, the famous Scottish economist, wrote in his classic book, The Wealth of Nations (Smith 1910 [orig. 1776]). In this frequently quoted passage, Smith talks about the way pins were made in eighteenth-century England:

One man draws out the wire, another straights it, a third cuts it, a fourth points it, a fifth grinds it at the top for receiving the head; to make the head requires two or three distinct operations; to put it on is a peculiar business, to whiten the pins is another; it is even a trade by itself to put them into the paper; and the important business of making a pin is, in the manner, divided into about eighteen distinct operations, which, in some manufactories, are all performed by distinct hands, though in others the same man will sometimes perform two or three of them.

Organizations, such as Adam Smith’s pin factory, create distinct jobs in order to increase productivity. Adam Smith remarked that in one particular pin factory, ten men, specialized in their work, were able to produce about twelve pounds of pins in a day—approximately 4,800 pins each.

But if they had all wrought separately and independently, and without any of them having been educated to this peculiar business, they certainly could not each of them have made twenty, perhaps not one pin in a day.

Smith supplies the reasons for the enormous productivity increases arising from division of labor: (1) the improved dexterity of the worker from specializing in one task, (2) the savings in time otherwise lost in switching from one task to another, and (3) the development of new methods and machines that come from specialization.

All three reasons lead to the prime element that connects division of labor to increased productivity: repetition. The relationship works this way: Specialization leads to repetition, which in turn produces expertise and, finally, increased productivity. It is a rational approach for organizations, even small organizations, to divide work into distinct, somewhat limited jobs. And what was true in Adam Smith’s time is still true today: Specialization via the division of labor increases productivity.

Organizations usually divide work both horizontally and vertically. Horizontal division of labor is the separation of a large job (such as pin making) into distinct, smaller jobs (Smith’s eighteen distinct operations) so that repetition, expertise, and increased productivity will result. Vertical division of labor is the organizational hierarchy, the system of superior/subordinate relationships linked from the lowest to the highest levels within an organization.

Because organizations must divide labor—both horizontally and vertically—structural conflict is inherent in practically all organizational settings. To understand conflict originating in horizontal and vertical specialization, consider the following case history: Sue Wong, a relatively new sales representative for Acme Machine Parts, was having difficulty with her boss, Greg Ryan, the sales manager for District 1. The difficulty culminated with this performance appraisal of Sue, which was placed in her HR file.

Sue Wong is a highly motivated, energetic woman who demonstrates above-average intelligence and commitment to her job. Nevertheless, she is still unable to comprehend how the basic products sold by Acme Machine Parts function. Her learning problems appear to be related to her lack of mechanical background and knowledge—knowledge most of our sales staff picked up as boys, taking apart their bikes and working on their cars. Sue was also an English major in college.

Because of these factors, her advice to our customers is frequently lacking in good judgment and, quite frankly, reality. Some of her advice has been so far off base it appears almost funny, except our customers don’t think so. In fact, ten major accounts have switched to the competition in the last two months, all because of Sue.

Because of these problems, I am forced to place Sue Wong on probation. If her performance during the next six months does not demonstrate substantial improvement, I will be forced to terminate her employment.

Sue Wong found this performance appraisal appalling and protested strongly to her boss. She requested that he modify the appraisal, take her off probation, give her additional training, transfer her to another territory, and reduce her sales quota. Her manager rejected all of these requests. Although Sue was angered by Greg’s response, she believed nothing could be done.

This example illustrates a basic structural conflict. Greg Ryan and Sue Wong are linked as supervisor and subordinate, a clear-cut vertical division of labor. Their conflict relates directly to the sales demands imposed on Sue by the organization through her superior.

To complicate matters, consider the following developments in this case: On the advice of a few other female employees in the company, Sue made an appointment to talk to Helen Poppos, the firm’s affirmative-action officer. Helen’s job was created nine years ago in response to government pressure to hire, retain, and promote women and minorities. Only 18 percent of Acme Machine Parts’ sales, professional, and managerial employees are female. Sue Wong had been one of the first females to sell the company’s machine parts product line.

Helen Poppos read Sue’s performance appraisal. She didn’t like what she read. Her initial reaction was that this was a potentially discriminatory appraisal designed to get rid of Greg Ryan’s only female sales representative.

The job of an affirmative-action officer is complex. Although the person in this position reports directly to the firm’s president, the job is primarily a staff function. As a general rule, staff positions advise the major line positions in the production, sales, and finance/accounting departments. The affirmative-action officer does not have the authority to tell a line manager what to do, but he or she can make it quite unpleasant for a manager because of the officer’s direct contact with the firm’s president.

Helen Poppos and Greg Ryan had a long conversation regarding Sue Wong’s situation. The meeting ended with this interchange:

GREG: |

Are you telling me I can’t evaluate my employees as I see fit? Do I have to sugarcoat evaluations for minorities and females? |

HELEN: |

Definitely not, Greg. My point is that Sue Wong is a valuable employee, and we need to keep her. You know what kind of record we have in hiring and keeping women. It stinks, and everybody, particularly the government, knows it. I’m just trying to work with you and Sue to settle this problem. |

GREG: |

There you go again—that word problem. I don’t have any problem with Sue. If she performs better in the next six months, I’ll keep her; if not, she’s out. It’s that simple. |

HELEN: |

Greg, it’s not that simple. You need to help Sue make it. This sink-or-swim attitude you have has got to be changed. |

GREG: |

I still don’t understand. What do you want me to do? Hold her hand? Come on, Helen. She’s a big girl. She’s got to do it herself. Nobody gave me any special help when I started out. |

HELEN: |

We keep going round and round on this. Let me make it simple. “Sue Wong is a highly motivated, energetic woman who demonstrates above-average intelligence and commitment to her job,” to quote your first line in her appraisal. We can’t afford to lose this type of person, no matter what the race, ethnicity, or sex. But this particular person is a woman, and we need to keep as many as possible, particularly the best ones. If you don’t help her in the next six months, and she fails your test, you say you’ll fire her. And I say I’ll stop you from doing that. |

GREG: |

How? How are you going to stop me? |

HELEN: |

I’ll go to the president if I have to, but I’ll stop you. That’s my job. |

Helen Poppos and Greg Ryan perform very different jobs for the organization. Normally, they have little reason to interact. But in this instance, they both feel a large responsibility for the problem of Sue Wong, even though their solutions to the problem appear quite contradictory. As affirmative-action officer, Helen Poppos wants the organization to do everything possible to retain Sue. As district sales manager, Greg Ryan wants her to improve her performance (without his help) within the next six months, or he’ll fire her.

The conflict between these two individuals is embedded clearly in the roles they perform at Acme Machine Parts. Thus, the conflict arises from structural causes. While values and personality may contribute to their difficulties, the disagreement appears to be rooted in structural conflict.

THE ROOT CAUSES

OF STRUCTURAL CONFLICT

As we have argued thus far, the very nature of modern organizations—their vertical and horizontal structure—contributes to conflict in the workplace. Management professors Jerald Greenberg and Robert A. Baron summarize these and other key factors that promote structural conflict as follows (Greenberg and Baron 1993, 372–374):

1. Competition over scarce resources is common to all organizations and can be seen in conflicts over the distribution of office space, salaries, employees, and supplies.

2. Ambiguity over responsibility or jurisdiction leads individuals to be uncertain of their exact duties; as a result, tasks that no one wants to do can lead to fights over who is going to do them.

3. Interdependence stems from the fact that many people in an organization cannot do their jobs without others first doing theirs; when these others falter, for whatever reason, they can find themselves engaged in a dispute with those who are dependent upon them.

4. Competitive reward systems can spur productivity, but they can also generate negative conflict within organizations when those losing out on bonuses and raises feel that the competition was biased or based on trivial distinctions among employees; the resulting resentment can result in antagonism.

5. Differentiation, as the example involving Helen Poppos and Greg Ryan shows, can fuel conflict. As the number of departments and divisions increases, “individuals working in these groups become socialized to them, and tend to accept their norms and values. As they come to identify with these work groups, their perceptions of other organization members may alter. They view people outside their units as different, less worthy, and less competent than those within it. At the same time, they tend to overvalue their own unit and the people within it” (Greenberg and Baron 1993).

6. Power differentials accentuate the contest within organizations between the norms of equity— the belief that organization members should be rewarded for their relative contributions—and equality, the belief that everyone should receive the same or similar outcomes. Where large power differentials exist, equity tends to prevail; however, this situation can lead those toward the bottom of the organizational chart to express dissatisfaction with the high levels of inequality.

Exhibit 2–3 summarizes the key predictors of structural conflict. We will explore these factors further and examine specific conflict resolution approaches for each in Chapter 3. You can anticipate some of these approaches by closely examining this exhibit and by recalling the basic tenets of principled negotiation presented in Chapter 1, then complete Exercise 2–1.

![]() Exercise 2–1

Exercise 2–1

Take the following quiz to test your understanding of structural conflict. Match the situation with the aspect of structural conflict to which it is most closely related. If you do not get all of the answers correct, go back and review the preceding section on structural conflict.

Aspect of Structural Conflict:

(a) Ambiguity over responsibility

(b) Competition for scarce resources

(c) Interdependence among work assignments

(d) Competitive reward systems

(e) Differentiation

(f) Power differentials

Situation:

1. The budget allows for only six new computers this coming year, and the head of maintenance needs five of them, but the team leader of overseas sales also wants five. Tension between the division head and the team leader ends in heated argument.

Answer _______

2. Several professors in the Information Technology Department of the local private university complain to the vice president for academic affairs that the admissions office is admitting inferior students, and that this results in many students dropping out and a declining number of IT majors. The head of the admissions office lodges her own complaint with the same vice president—that professors in IT do not make time to meet with prospective students who have expressed an interest in majoring in IT, and thus many of the best ones are not enrolling at the university.

Answer _______

3. The computer server used by the sales department of a medium-size plumbing supplies manufacturer crashes, and important data are lost. When the head of the department contacts the information services department to get a backup copy of the data, he is told that backups are done only once a week, and that daily backups are the responsibility of the individual departments and their workers. The sales head is incensed and retorts, “Show me where in the company policies manual it says individuals are responsible for daily backups—that is why we have an information services department!” To which the head of information services responds, “We don’t need to write down every detail of how the work gets done here—everyone knows that this is standard operating practice, to do daily backups of your own data!”

Answer _______

Answers: 1. (b); 2. (c); 3. (a)

INTERPERSONAL CONFLICT

In Chapter 1, we specified that interpersonal conflict refers to conflict originating from differences in personalities and values. Personality was defined as a person’s typical patterns of attitudes, needs, characteristics, and behavior. Values are conceptions of what is good, desirable, and proper—or, conversely, of what is bad, undesirable, and improper. Interpersonal conflict is also magnified by biological and social differences—for example, differences in race, gender, national origin, age, income, marital status, religion, and physical disability.

Interpersonal conflict often begins with, or is magnified by, structural causes. The clash between Helen Poppos and Greg Ryan began as a structurally caused conflict. Their job demands were contradictory, and the issues surrounding Sue Wong brought these differing job requirements to the forefront. However, it is a rare person who can clash with another about an issue and feel no anger or resentment. This is particularly true if the conflict results in obvious winners and losers.

Consider the following developments in the Sue Wong controversy: Six months after the first appraisal, Greg Ryan informed Sue Wong that he was terminating her because of her unacceptable sales results. He then completed the paperwork necessary to implement his decision. Because a woman was involved, the human resources department routed the paperwork to Helen Poppos. Helen called Greg and tried to change his decision, but Greg refused to listen, even though he admitted Sue had received no additional training or special assistance during the six-month probationary period.

Helen Poppos felt compelled to bring this issue to the president’s attention. Because the government was pressuring the company to place more minorities and women in better jobs, the president took the advice of the affirmative-action officer and reversed the termination decision. The fact that Greg Ryan had not helped Sue in any meaningful way during the previous six months was another significant factor in the president’s decision. Subsequently, Greg Ryan refused to speak to or even acknowledge Helen Poppos whenever they crossed paths. Helen made a point to say hello to Greg in the hall or in the lunchroom, but Greg always looked the other way. The relationship between these two individuals deteriorated to an extremely low level.

Many observers would characterize the conflict between Greg and Helen as an interpersonal one, even though its origins are structural. Because he lost a battle with Helen, Greg Ryan became hostile toward her. It will not take long for Helen Poppos to respond in kind. Both individuals will become more unfriendly and, given the opportunity, perhaps even try to undermine each other.

Consider the following developments in this case: Greg Ryan was forced to retain Sue Wong, but he didn’t like it and certainly wouldn’t forget what he thought she did to him. As a result, their relationship deteriorated. Greg would either not speak to Sue, or, when he did, he would criticize her. After seven months of this treatment, Sue Wong left the firm and went to work for another machine parts company. In her exit interview with Helen Poppos, she blamed Greg Ryan for her decision.

Not only was Helen upset about the Sue Wong debacle, but she vowed to do something about Greg Ryan. Whenever she had an opportunity, she would bring up the incident with Sue as an example of why the company had affirmative-action problems. Because she had access to top management, even the president heard a lot about Greg Ryan. It was going to be slow, but Helen Poppos knew she would eventually get what she wanted—to make Greg Ryan leave the company or get pushed out.

The friction between Greg Ryan and Helen Poppos evolved into an extremely intense interpersonal conflict. Neither individual could be characterized as obnoxious or hostile by nature, but they revealed these traits when dealing with each other.

This situation is an example of what psychologists and other behavioral scientists term escalating conflict. Conflict tends to be episodic in nature—one conflict episode leads naturally to another. As the loser in a previous episode tries to get even in a subsequent episode, the conflict moves inexorably from the impersonal to the very personal.

To demonstrate the pervasiveness of escalating conflict and its connection to interpersonal factors, psychologist Vello Sermat conducted two experiments in which test subjects played games against opponents (Sermat 1978). In one game, the experimental subjects played against a machine that was programmed to respond exactly as each subject had acted toward it. In the other, the subjects played against members of the research team who had been instructed to respond in a reciprocal manner toward the test subjects. In these games, cooperation with opponents usually resulted in higher payoffs to both sides.

When playing against the machine, the subjects learned to act cooperatively to maximize their total payoff, even when by doing so the machine also benefited. But when the opponent was a person, a reverse effect occurred. At the end of thirty trials in the machine-opponent series, the subjects had cooperated 90 percent of the time. In the personal-opponent series, they had acted aggressively about the same percentage of the time, even though they had reduced their own payoff by behaving in that manner. From these results, it can be seen that preventing their human opponents from winning was more important to the test subjects than maximizing their own payoff. In other words, beating the other person became much more critical than obtaining a higher objective reward.

Within organizations, interpersonal conflict intensifies as one conflict episode leads to another and as the participants engage in escalating conflict. Retaliation encourages further retaliation, and conflict deepens and becomes much more difficult to resolve. We explore conflict resolution approaches to interpersonal conflict in Chapter 4. Remember, you can anticipate some of these approaches if you recall the basic tenets of principled negotiation presented in Chapter 1.

![]() Think About It

Think About It

Think about a time when you were either directly involved with or witnessed an escalating conflict. Briefly describe the conflict and the factors you think led to its escalation. What could have been done to de-escalate it?

_____________________________________________

_____________________________________________

_____________________________________________

_____________________________________________

_____________________________________________

_____________________________________________

CONSTRUCTIVE VERSUS DESTRUCTIVE

CONFLICT AND CONFLICT RESOLUTION

In discussing our final method of categorizing conflict, we must consider the issues surrounding good and bad conflict. There are many managers who believe that conflict is automatically bad. Conflict makes them uncomfortable, and they immediately begin to search for methods to eliminate it. Nevertheless, effective managers are aware that some conflict in an organization is valuable. Remember our definition: Conflict is a process that begins when one party perceives that another has negatively affected, or is about to negatively affect, something that he or she cares about. So how can negatively affecting what another person cares about be interpreted as valuable?

Consider this example: A number of years ago, the top management of a major regional supermarket company deliberately changed the managerial structure in order to stir up conflict between district managers and store managers, who supervised the individual supermarkets, and the produce managers and merchandisers, who were responsible for the produce departments in each store. At one meeting, the vice president of sales, the executive in charge of all store operations, made the following comment in a conversation with a trainee and a district manager:

One of the things I’ve noticed while I’ve been with some of the produce merchandisers is that they’re having a lot of trouble convincing some store department heads to give them enough space for their merchandise. Last week, for instance, I was assigned to a produce merchandiser who was trying desperately to get space so he could offer a special on roses. | |

DISTRICT MANAGER: |

Now hold on there! I don’t think he had such a tough time. |

VP OF SALES: |

Well, if he did, I’m glad to hear it. I’d much rather hear that people are fighting for space than hear they’re being apathetic about it. I like to see some of that kind of fighting going on in the organization. It’s only when it stops that I begin to worry about it. |

The vice president of sales used the word apathetic to describe what happens to people if there is no competition, which is a low-level form of conflict. Other words, such as stagnant and resistant to change, could have been used. Most organizations need to resist stagnation and apathy, and a little competition can do much to offset them.

Even conflict that goes beyond friendly competition can be positive for the organization because it reveals flaws in how things are presently arranged. Properly resolved, such conflicts result in a better-running organization and a generally more satisfied workforce. Sociologists and historians have long recognized the benefit of conflict to promote positive change in social arrangements; had there been no civil rights movement in the 1950s and 1960s, the South would still be suffering from the evils of segregation today. In economic terms, social arrangements that reward or punish individuals for reasons other than their performance (for example, skin color, national origin, or gender) are usually less efficient, productive, and profitable. Certainly, the South has been much more prosperous since the dismantling of the racist social system that existed before the mid-1960s.

Let’s extend our contention that conflict and its proper resolution can be beneficial for an organization and the individuals working in it by referring to the example we’ve been using throughout this chapter. Was the conflict between the affirmative-action officer, Helen Poppos, and the district sales manager, Greg Ryan, constructive or destructive? In the end, it was clearly destructive. Each person was trying to frustrate the other, and the organization was suffering. But the conflict was not automatically destructive: In the initial stages, the organization was probably benefiting. If the conflict had led to the following resolution, most observers would characterize it as constructive. (As you read the exchange between Greg and Helen, try to identify those aspects that indicate principled negotiation, referring to Exhibit 1–2.)

We can see in this exchange that Greg and Helen have separated the people from the issues. For example, in the first exchange, Helen accused Greg of having a “sink-or-swim attitude.” Such an accusation would serve only to put Greg on the defensive; in contrast, in the last exchange, Helen acknowledges that there is a problem with Sue Wong that goes beyond Greg’s attitudes. Note, too, that in the first exchange Helen and Greg did not agree on an objective standard to help settle their dispute; rather, Helen focused on Sue’s intelligence and the fact that she was a woman, while Greg focused on her poor performance with clients. In contrast, in the last exchange Greg and Helen came to an agreement that “mechanical training” was an essential and fair standard by which to evaluate prospective and current sales staff. Further, through their openness and willingness to communicate, they invented an option for mutual gain: sending unqualified salespeople back to school to get the training. Neither Greg nor Helen focused on their initial positions, but, rather, both took a step back and focused on interests. They have the common interest of organizational productivity, but they have differing interests in the degree to which each wants to hire and maintain female employees. By concentrating on these interests without taking firm initial positions, Helen and Greg were eventually able to arrive at a wise agreement, that is, one that (1) met the legitimate interests of each party, (2) improved the relationship between each party (or, at least, did not damage it), and (3) took organizational interests into account.

It’s difficult to distinguish precisely between constructive and destructive conflict. Nevertheless, we have an established standard: organizational performance. If the organization performs better because of the conflict and the form of its eventual resolution, then conflict was constructive; if performance drops, the conflict was destructive. In short, remember that conflict can spark positive change in an organization through the proper resolution of the conflict. And the proper resolution of the conflict should first be sought in the tenets of principled negotiation.

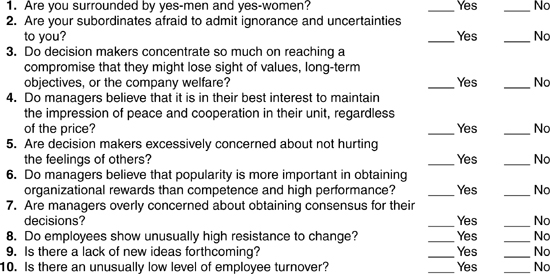

Recognizing the positive benefits of friendly competition and properly resolved conflict, managers should make sure that there is not too little tolerance of competition and conflict in their departments, teams, or organizations. Think about your department, team, or organization as you answer the ten questions in Tool 2–1.

Conflict Resolution Tool Box

Conflict Resolution Tool Box

Tool 2–1 Assessing Whether There Is Too Little Tolerance of Competition and Conflict in My Department, Team, or Organization

Instructions: Respond either Yes or No:

Total the number of Yes answers. As the number of Yes answers increases, so does the probability that your department, team, or organization is stagnating and would thus benefit by raising its tolerance for competition and conflict. Even a single Yes answer suggests the need for an increase in such tolerance.

Adapted from Stephen P. Robbins, “‘Conflict Management’ and ‘Conflict Resolution’ Are Not Synonymous Terms,” California Management Review, 1978, p. 71.

This chapter began by stressing the importance of conflict and conflict resolution as part of a typical manager’s job; it then presented various approaches to categorize conflict. Although each approach is quite different, they do not contradict each other. Instead, they are alternative ways to observe and understand conflict.

One approach categorizes conflict based on a manager’s involvement in the conflict and his or her relationship to the people engaged in it. The major tools managers can use to resolve conflict were also identified: authority, creativity, and principled negotiation.

A second approach divides conflict into two basic types. Structural conflict arises from the jobs and departments that exist in an organization and the relationships among them; it is magnified by competition over scarce resources, competitive reward systems, interdependence among work units, power differentials, and ambiguity over responsibilities and jurisdictions. Interpersonal conflict originates from personality and value differences and is magnified by social differences (such as age, race, and gender). Interpersonal conflict often begins with, or is magnified by, structural conflict, as conflicts that arise from the organization can result in anger or personal resentment.

Finally, we identified two other types of conflict based on whether the conflict was properly resolved. Constructive conflict improves organizational performance by first identifying problems with the status quo and then resolving the conflict in a positive way. Conflicts resolved through principled negotiation are most likely to result in improved organizational performance and high employee satisfaction. Destructive conflict impairs organizational performance and indicates an improper approach to conflict resolution.

The chapter concludes that departments, teams, and organizations must allow more than minimal levels of tolerance for conflict, because conflicts can point to problems in the department, team, or organization that, if properly resolved, will improve performance and make for a more satisfied and productive workforce.

1. Learning to resolve conflict effectively is important to becoming a good manager because: |

1. (d) |

(a) managers spend a lot of their time trying to either resolve conflict or avoid it. |

|

(b) conflict can reveal flaws in the organization of a company and, properly resolved, can fix these flaws. |

|

(c) it frees the manager from the mistaken notion that conflict is automatically bad. |

|

(d) all of the above. |

|

2. Which of the following best exemplifies how principled negotiation can prevent a budding conflict from becoming destructive for the organization and increase the chances that it will become constructive? Encourage each party involved in the conflict to: |

2. (c) |

(a) take a strong, clear initial position so that no one mistakes the motivations and goals of everyone involved. |

|

(b) work on a single solution for the problem at hand. |

|

(c) focus on their real interests and not so much on taking a strong initial position on the best way to realize them. |

|

(d) give up something to attain a compromise. |

|

3. Which of the following promotes structural conflict? |

3. (d) |

(a) Competition over scarce resources |

|

(b) Socially based personality differences, such as sex or age |

|

(c) Interdependence between work units |

|

(d) a and c. |

|

4. Interpersonal conflict refers to conflict originating from: |

4. (a) |

(a) personality and values. |

|

(b) competition over rewards. |

|

(c) the jobs people hold in organizations. |

|

(d) competition over scarce resources. |

|

5. In the second exchange between Greg Ryan and Helen Poppos, the conflict yielded benefits for the organization; in contrast to the first exchange, in the second exchange Greg and Helen: |

5. (d) |

(a) separated the people from the issues and developed an option for mutual gain. |

|

(b) used an objective standard on which to settle their dispute. |

|

(c) focused on their interests instead of beginning the exchange with firm positions. |

|

(d) all of the above. |