4

Resolution of Interpersonal Conflict

Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter, you should be able to:

• Describe the seven basic approaches to resolving interpersonal conflict.

• Specify the five key rules for communicating with the opposite sex when using coaching as a conflict resolution approach.

• Specify the six principles for maintaining a culturally neutral position when interacting with employees from a different country, region, or ethnic background.

• Give three reasons why conflict resolution by walking is generally better for the resolution of interpersonal conflict than electronic communication.

• Describe at least one benefit of the asynchronous nature of electronic communication for the resolution of interpersonal conflict.

INTRODUCTION

This chapter will continue the examination of conflict resolution techniques, focusing on interpersonal conflict and its resolution. Interpersonal conflict results from clashes in personality and/or values. Unlike structural conflict, which arises from the jobs, departments, and teams within an organization, interpersonal conflict originates from the individuals holding those jobs and working in those departments or teams.

As previously stated, it’s often difficult to separate structural conflict from interpersonal conflict, because in many instances structural conflict can lead to intense personal conflict. It is uncommon for human beings to engage in structural conflict and remain purely objective about it. Nevertheless, in the following examples of conflict, structural factors will be minimized and interpersonal factors stressed.

LAKE CITY MANUFACTURING: A CASE STUDY

Lake City Manufacturing is a large, well-established manufacturing company, producing parts used by the auto industry. Lake City has a policy of hiring high school and technical school graduates for its production facilities; however, lately there’s been a campaign to hire more college-educated employees for the production area. While some of these new employees have degrees in engineering, most of them have business or liberal arts degrees. It is expected that they will either move into managerial positions or leave the organization within two years.

There have been minor clashes between the college- and non-college-educated employees, but no widespread problems. However, Carol Freedman, a senior-level manufacturing manager and a college graduate herself, has been involved in an open conflict between two of her best supervisors.

Chuck Simmons, a fifty-five-year-old maintenance supervisor, has worked at Lake City for thirty-one years. He graduated from a vocational school and is considered an expert on the machinery used at Lake City. While Chuck and his maintenance people will never set any speed records for completing their work, they are reliable and quality-oriented. When Chuck’s department repairs something, it’s done right. Chuck won’t tolerate sloppy work.

Jorge Lopez, a twenty-four-year-old production supervisor, has worked at Lake City for only two years. He graduated from a business college and is considered by almost everybody to be on the fast track. While Jorge has limited production experience, he is viewed as one of the best supervisors in the entire plant. Intelligent, impatient, and somewhat abrasive, Jorge is described by some as an “acquired taste.” He has a reputation for being a pusher, demanding the maximum from his subordinates and the machinery they use. Jorge Lopez wants to make his mark at Lake City and boasts he’ll be the youngest vice president in the company’s history.

Unfortunately, Chuck Simmons and Jorge Lopez don’t get along, and it has reached the point where they openly express their dislike of each other. Carol Freedman is well aware of this situation and views it as one of her worst managerial problems. Here’s what Carol has to say about this problem:

Sometimes it gets so bad I’d like to get rid of them both. Let me tell you about them. I consider Jorge Lopez to be a real hot dog. You know the type. Always bragging about this or boasting about that. He’s an arrogant, insufferable pain in the neck. But he’s also very bright and very productive. I can always count on Jorge to meet his quota, no matter what. It’s a point of pride for him. He may end up being the youngest vice president in the company, as he’s always claiming, unless, of course, somebody stabs him in the back first.

Now Chuck Simmons is the exact opposite. He’s a real sweetheart. Friendly, patient, sensitive, I could go on and on about him. Chuck’s the kind of guy you’d want for your next-door neighbor or grandfather. Chuck and his maintenance guys are slow, but sure. They’re a bunch of perfectionists, concerned much more about quality than time.

Jorge and Chuck are constantly fighting. It’s always the same issue. A machine breaks down in Jorge’s department and he wants it fixed immediately. Chuck and his guys get there quick enough but never seem to fix it as fast as Jorge demands. Jorge rants and raves and calls Chuck all kinds of names. Chuck never resorts to name-calling. Oh no. He gets even in his own way. He slows down even more. And he finds other things wrong, usually traceable to some neglected oiling or cleaning Jorge’s people should have done. These arguments sometimes end up in my office.

Sometimes I’d like to strangle both of them. But Chuck Simmons is a wonderful person and an excellent worker. And Jorge Lopez is the most productive pain in the neck you could want. I need them both, but not their constant fighting.

While this struggle has structural aspects (the reciprocal interdependence between maintenance and production), the conflict between Jorge and Chuck is also rooted in their personality differences. Recall that personality refers to a person’s typical patterns of attitudes, needs, characteristics, and behaviors. Psychologists speak of personality in terms of traits, for example, shyness, hostility, talkativeness, and seriousness. Traits are generally consistent sources of behavior; consequently, knowledge of an individual’s traits allows his or her actions to be predicted.

It is clear that Chuck Simmons and Jorge Lopez have different personalities. To demonstrate this, examine the sixteen traits listed in Tool 4–1. (These sixteen traits are not the only ones that psychologists recognize; however, those listed determine behavior in most situations.) Based on what you now know about Chuck Simmons and Jorge Lopez, assign source traits to each one. If you have insufficient information, do not assign a trait. Take about five minutes to do this, then continue reading. (You can use the display for Tool 4–1; let Individual A represent Chuck Simmons, and Individual B represent Jorge Lopez. Pencil in check marks along the continuum for each personality trait that you think is applicable.)

Conflict Resolution Tool Box

Conflict Resolution Tool Box

Tool 4–1 Identifying Personality Traits

Instructions: Complete the following inventory to identify the personality traits of the two parties involved in a conflict. For practice, apply the inventory to the conflicting parties in the case study in this chapter, letting Chuck Simmons be Individual A and Jorge Lopez be Individual B.

Reprinted and adapted with permission from R.B. Cattell, “Personality Pinned Down,” Psychology Today, July 1973, (©1973, Sussex Publishers, Inc.).

Because personality differences so often form the basis of interpersonal conflict, you can sometimes begin your resolution of interpersonal conflict by identifying the personality traits of the individuals involved. Such an analysis may reveal to you, in stark fashion, key personality differences between the disputing parties. These differences may lie at the root of the conflict.

The situation between Chuck and Jorge is a perfect example of this. From the information given, Chuck Simmons, the maintenance supervisor, appears to be reserved, intelligent, affected by feelings, serious, conscientious, sensitive, trusting, practical, conservative, controlled, and relaxed. On the other hand, Jorge Lopez, the production supervisor, appears to be outgoing, intelligent, dominant, serious, expedient, venturesome, tough-minded, practical, forthright, self-assured, experimenting, self-sufficient, and tense.

Ascribing traits on the basis of limited information is, of course, an unscientific process; however, assuming even minimally reasonable accuracy, it is not difficult to explain why Chuck Simmons and Jorge Lopez have an interpersonal problem. Many of their traits are at opposing ends of the spectrum. It is not surprising that a conscientious, sensitive, conservative person would have problems dealing with an expedient, tough-minded, experimenting one. Because of fundamental differences in personality and values, a significant interpersonal conflict has developed between these two supervisors.

![]() Think About It

Think About It

Think about a personality conflict you’ve witnessed (or experienced) in your own workplace. Could knowledge of basic personality types have made a difference in how the conflict was resolved?

_____________________________________________

_____________________________________________

_____________________________________________

_____________________________________________

_____________________________________________

_____________________________________________

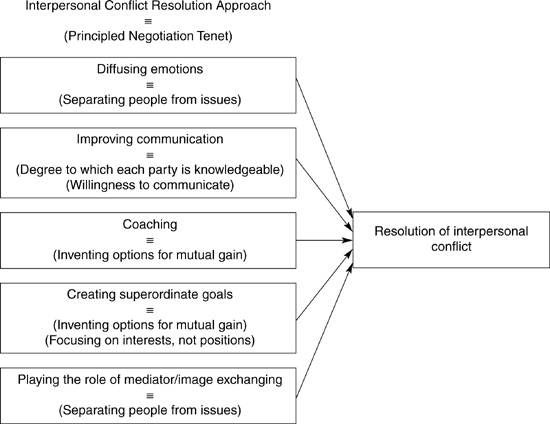

INTERPERSONAL CONFLICT RESOLUTION APPROACHES

A manager cannot change a person’s personality or basic values. These fundamental traits and deep-seated beliefs can usually be changed only through a time-consuming therapeutic process. Think of how absurd it would be if Carol Freedman told Jorge Lopez, “I want you to be conscientious, sensitive, conservative, and nonabrasive starting right now.” Even if Jorge wanted to alter his personality in this way, he would be unable to do it without considerable professional help. Nevertheless, it is possible for a manager to help an employee modify the behavioral consequences of his or her personality and values. The following behavioral approaches to conflict resolution can be effective if used by a knowledgeable manager.

Coaching

One major element in the traditional process of management is directing subordinates. Telling them what to do is one form of directing, but coaching is more subtle. When managers coach subordinates, they are advising the subordinates on what should be done and why. Sometimes, just by asking the right questions, a manager can provide solid, albeit indirect, advice to an employee. If you are a team leader in your organization, your leadership style is expected to be like that of a coach; indeed, it is likely that you lack the formal authority to dictate or demand much of anything. But even if you are working within a traditional hierarchy and have the authority to resolve conflict via forcing (as described in Chapter 1), many organizational experts have come to the conclusion that the coaching approach is the best approach to management. In the words of Bianco-Mathis, Nabors, and Mathis, the authors of the critically acclaimed Leading from the Inside Out (Bianco-Mathis et al. 2002), the professional workplace of the twenty-first century is evolving in new directions:

Not only are workers’ needs different than they were 25 years ago, but demographic changes make recruitment and retention of skilled employees a critical issue. As a leader in the 21st century, you must be aware of and accept followers for who and what they are. Trying to change your employees to reflect the attitudes of a bygone era is a losing proposition.

Two major characteristics of workers today make coaching the ideal way of leading: the desire for choices and the immediate need for information. Workers today want flexibility—in their actions, thoughts, lifestyles, methods, and approaches. For them, unlike their grandparents’ generation, job security is no longer the overriding concern. Workers today want more than a paycheck. They want a lifestyle that meets both their personal and professional needs. As a coaching leader, you must provide options and choices to the members of your organization. Employees today expect to make decisions on a variety of alternatives and to take actions leading to a variety of outcomes.... Coaching is about recognizing that everyone is acting with intention and making choices that are consistent with what he or she finds important, meaningful, and satisfying. Being a coaching leader means giving employees the power and opportunity to exercise choices that will make their lives meaningful and contribute to organizational success.

Tool 4–2 presents guidelines for coaching employees involved in an organizational conflict that have been successfully used in many contemporary work settings.

Conflict Resolution Tool Box

Conflict Resolution Tool Box

Tool 4–2 Guidelines for Coaching Employees

As discussed in this chapter, it is possible for a skillful manager or team leader to use a coaching approach to resolving interpersonal conflict. Here is a set of guidelines that has been successfully used in many modern work organizations. The employee may be a subordinate, a team member, or a colleague (another manager or team leader).

1. The manager should listen to the employee in a patient, friendly, but intelligently critical manner.

2. The manager should not display any kind of authority.

3. The manager should not give moral admonition.

4. The manager should not argue with the employee.

5. The manager should talk or ask questions only under certain conditions:

a. To help the employee or team member talk

b. To relieve any of the employee’s or team member’s fears or anxieties that may be affecting his or her relationship with the manager

c. To praise the employee or team member for describing his or her thoughts and feelings accurately

d. To direct the discussion to some topic that has been omitted or neglected

e. To discuss implicit assumptions, if this is advisable

6. The manager should take the time to put himself or herself in the shoes of the employee—that is, to empathize.

7. The manager should assist the employee in developing and evaluating alternative courses of action to resolve the conflict at hand.

8. The manager should be slow to give advice, instead letting what the manager thinks is the best outcome ultimately come from the employee.

Adapted from Stephen P. Robbins, The Administrative Process (Prentice Hall, 1980), and Virginia E. Bianco-Mathis, Lisa K. Nabors, and Cynthia H. Roman, Leading from the Inside Out: A Coaching Model (Sage, 2002).

Gender differences between manager and employee may complicate the coaching relationship. As is well established in both the scientific and the popular press, men and women have different communicating styles. In their classic work Women and the Art of Negotiating (Nierenberg and Ross 1985), management experts Juliet Nierenberg and Irene S. Ross observe that this poses special problems for a manager when dealing with employees of the other gender. For women managers dealing with male employees, it is of particular importance to get men to listen and expose their feelings. Nierenberg and Ross observe that men tend to be less interested in discussing many topics that interest women, such as relationships. Men also tend to be less interested in small talk. Finally, men tend to interpret the soft, tentative speaking styles that are characteristic of many women as evidence that what women are saying is not that significant. It is therefore important for female managers to try to change these male perceptions, which can be accomplished, in part, using Tool 4–3.

Conflict Resolution Tool Box

Conflict Resolution Tool Box

Tool 4–3 How Female Managers Should Coach Male Employees

Female managers face special problems in communication when trying to coach male subordinates. The problems are rooted in the different communicating styles that men and women have been socialized into from youth through adulthood. If you are a woman manager with men reporting to you, the following guidelines for communicating with men are essential to follow when trying to coach them.

1. Be succinct.

2. Organize your thoughts before delivering them so that the message is clear and straightforward.

3. Pay attention to voice tone, intonation, and pitch; vary these to focus your listener’s attention.

4. Make eye contact.

5. Speak appropriately and focus on the topic under discussion. Limit personal or non-business-related conversation.

Adapted from Juliet Nierenberg and Irene S. Ross, Negotiate for Success: Effective Strategies for Realizing your Goals (Chronicle Books, 2003), and Women and the Art of Negotiating (Simon & Schuster, 1985).

Male managers can use some of this information in Tool 4–3 (being organized, paying attention to voice style, and making eye contact) and some of it applied in reverse (being willing to open up and reveal some things about their lives apart from the workplace). Most important, they can consciously avoid interpreting the soft, tentative speaking styles that are characteristic of many women as evidence that what women are saying is not that important. According to Georgetown University Professor of Linguistics Deborah Tannen, men who don’t understand how women have been socialized to communicate differently from men will be too quick, and often mistaken, in jumping to the conclusion that a particular woman lacks confidence; by the same token, women who don’t understand this difference will be too quick, and often mistaken, in jumping to the conclusion that a particular man is arrogant. In her best-seller Talking from 9 to 5: Women and Men in the Workplace, Professor Tannen provides an excellent description of this problematic aspect of gender differences in communicating style:

Though we think of these as individual weaknesses, underconfidence and arrogance are disproportionately observed in women and men respectively, because they result from an over-abundance of ways of speaking that are expected of females and males. Boys are expected to put themselves forward, emphasize the qualities that make them look good, and deemphasize those that would show them in a less favorable light. Too much of this is called arrogance. Girls are expected to be “humble”—not try to take the spotlight, emphasize the ways they are just like everyone else, and deemphasize ways they are special. A woman who does this really well comes off as lacking in confidence. Ironically, those who learn the lessons best are most in danger of falling into traps laid by conversational conventions (Tannen 1994, 42).

In summary, you must realize and be sensitive to the fact that men and women have tendencies to communicate with different styles and do not confuse the style with the substance of what is being said. You must use your knowledge of these stylistic differences to elicit more information that might be needed to help you resolve the conflict at hand.

Cultural differences between a manager and an employee may also complicate the coaching relationship. And as is also well established in both the scientific and the popular literatures, individuals from different cultural backgrounds often have different communicating styles. Because one cannot always anticipate the cultural background of an employee, the manager needs a general strategy for getting off on the right foot and keeping the lines for communication open. Daisy Kabagarama, an expert on the art of cross-cultural understanding, suggests in her widely read Breaking the Ice: A Guide to Understanding People from Other Cultures that the manager begin with a culturally neutral position in getting to understand an employee from a different country, region, or ethnic background (Kabagarama 1997). Such a neutral position requires the right attitude—an attitude that is encouraged by heeding the recommendations found in Tool 4–4.

Conflict Resolution Tool Box

Conflict Resolution Tool Box

Tool 4–4 Interacting with Employees from a Different Country, Region, or Ethnic Background

If your work organization is not already characterized by diversity, it will be soon enough. If you are working with a large number of individuals from a particular cultural background (say, Latinos from northern Mexico or first-generation immigrants from Nigeria), it makes sense for you to study materials on that particular culture. In general, however, your best approach to diversity, especially when you are managing individuals from a background different from your own, is to take a culturally neutral position; this will ensure your greatest success in understanding the employee from a different country, region, or ethnic background. Such a position is encouraged when you have the following mind-set:

1. Genuine interest

2. A sense of curiosity and appreciation

3. Empathy

4. A nonjudgmental attitude

5. Flexibility

6. Childlike learning mode

The meaning of each of these should be fairly obvious, except perhaps for the last. Having a childlike learning attitude is not the same thing as being childish. A childlike learning mode is comparable to an empty slate, free of preconceived ideas. Whereas a childish question might be “Do you have houses where you come from?,” a childlike question is “What kind of houses do you have where you come from?” The first type of question might arouse anger and prompt a sardonic reply like “No, we do not have houses; we all live in trees.” The second one, however, expresses genuine interest and eagerness to learn. It might prompt an answer like “We have different types of houses . . .”

Adapted from Daisy Kabagarama, Breaking the Ice: A Guide to Understanding People from Other Cultures, second edition, (Allyn & Bacon, 1997).

The mind-set portrayed in Tool 4–4 does not come naturally, and we would fully expect that you have sometimes fallen into the very natural human tendency to stereotype individuals from a cultural background different from your own. Pause here for a few minutes and take stock of some of the stereotypes you have developed—and see how they stand in stark contrast to recognizing the basic humanity in each of us, from avoiding being judgmental or lacking empathy.

![]() Think About It

Think About It

Think about the stereotypes that you have developed over the years about individuals coming from groups different from yours. Write down at least two of these for each of the following. Our advice is to resist these stereotypes when interacting with such individuals in the future.

African Americans (If you’re African American, then Whites):

_____________________________________________

_____________________________________________

_____________________________________________

_____________________________________________

Southerners (If you’re from the South, then Northerners):

_____________________________________________

_____________________________________________

_____________________________________________

_____________________________________________

Mexican Americans or Puerto Ricans (If you’re Mexican American or Puerto Rican, then Anglos or mainland Whites):

_____________________________________________

_____________________________________________

_____________________________________________

_____________________________________________

Some managers may not feel comfortable coaching employees. They think it places them in the role of therapist—a role they feel ill-equipped to play. Or they simply prefer the direct approach and a massive use of their authority: “Change, or else!” As we have already pointed out in this chapter, and as we do so many other places in this course, such a mind-set is becoming more and more out of step with the cultures of most contemporary work organizations, which increasingly emphasize equality, equity, and employee input in maintaining and improving company operations.

Indeed, it is our experience that the number one way in which organizations can avoid the kind of costly litigation and the more expensive forms of ADR (alternative dispute resolution) discussed in Chapter 1 is to encourage their managers and team leaders to treat their coworkers and subordinates with respect—to be tough on logic, to be tough on data, but to be soft on people (a bedrock idea underlying coaching as well as the principled negotiation approach to conflict resolution emphasized throughout this course). We have found that by following the guidelines in Tools 4–2, 4–3, and 4–4, most managers can become skillful at coaching, and that most organizations will fare better when their managers make it a common alternative in resolving interpersonal conflict.

Consider the following coaching session between Carol Freedman and her abrasive production supervisor, Jorge Lopez. Pay attention both to what Carol says and to how she says it:

JORGE: I don’t know why you want to talk to me. The problem’s Chuck Simmons. Sometimes I think he’s in perpetual slow motion.

CAROL: (Maintaining eye contact) Jorge, do you really think that Chuck’s the whole problem?

JORGE: No, of course not. I know I fly off the handle sometimes. He can be so aggravating and I’m an impatient guy. I can’t stand waiting around for anybody.

CAROL: (Friendly, empathetic tone) Jorge, I know you don’t want to fight with Chuck all the time. So what can you do to minimize the conflict?

JORGE: Leave the department whenever Chuck’s around—that’s what I can do. I can’t yell at him if I’m not there.

CAROL: (Raising the pitch of her voice) That’s an idea. Do you think it would really work?

JORGE: Probably. I’m certain I waste even more of my time by arguing with Chuck. And I’m convinced he slows down to spite me when I get mad. If I’m not there, Chuck and his guys would take less time, and my blood pressure would stay normal.

CAROL: (Maintaining eye contact; friendly, empathetic tone; raising the pitch of her voice) Well, would you like to give it a try? Get out of the department whenever the maintenance people show up?

JORGE: I can’t do it all the time. But I can try it and see if it works. It certainly couldn’t make the situation any worse.

A careful examination of Carol Freedman’s part of the dialogue reveals that she followed Nierenberg and Ross recommendations by using a subtle approach. Most of the time she asked questions. This enabled Jorge Lopez to crystallize his thoughts. In addition, Carol remained restrained and nonjudgmental throughout the entire conversation. The only remarks she made that were not questions were “Jorge, I know you don’t want to fight with Chuck all the time” and “That’s an idea.” Both comments were designed to keep Jorge from becoming defensive.

It’s also important that Jorge Lopez came up with the idea for reducing the conflict. Because it’s his idea, Jorge will feel ownership and a greater commitment to its success. If Carol had said, “Jorge, I want you to leave your department every time a maintenance guy shows up,” Jorge probably would have resisted the approach. As it was, Jorge was eager to try out his idea, demonstrating some pride in it. Note how this fits in with the principled negotiation strategy presented in Chapter 3, specifically, the tactic of getting the employee to suggest options for resolving the dispute.

While coaching can be effective, it is not the only approach to resolving interpersonal conflict. Defining both acceptable and unacceptable behavior and their ramifications also is useful.

Modifying Behavior

Behavior modification is the shaping of another person’s behavior by controlling the consequences of that behavior. Decades of research led B.F. Skinner, the father of behavior modification, to conclude what has become a fundamental principle of human psychology: “Behavior is a function of its consequences” (Skinner 1953). What causes people to do the things they do? Most behavioral scientists believe that human behavior is rational, self-serving, and goal directed. The goal of our behavior is to satisfy our needs. If those needs are satisfied, we continue that behavior; if not, we stop it. If managers understand the fundamentals of behavior modification, they can shape their subordinates’ behavior without getting involved in personality issues or deep-seated values. The same can be said for peer relationships—for example, a manager dealing with another manager, or a team member dealing with another team member. Behavior modification is based on the following principles: People will continue a behavior if they are rewarded for it, particularly if the reward occurs soon after the behavior; people will stop behaving in a certain way if they are not rewarded, or if they are punished for the behavior. The rewards must be valued by the employee—in other words, they must satisfy his or her needs.

From the managerial perspective, the keys to modifying behavior are the rewards, nonrewards, and punishments managers can produce to reinforce or eliminate certain employee behaviors. In addition, the frequency and timing of these rewards, nonrewards, and punishments are important.

Continuous reinforcement occurs when a manager responds with rewards or punishments every time an employee performs a certain behavior. For example, suppose an employee tends to be late returning from breaks. A manager could continuously reinforce acceptable behavior by praising this employee whenever he or she is not late or continuously punish unacceptable behavior by scolding that person whenever he or she is late.

Intermittent reinforcement means that a manager responds to an employee’s behavior either randomly or at some regular frequency (such as every fourth or fifth occasion) with rewards or punishments. For example, if an employee is late returning from a break, the manager would scold that person only sometimes. If the employee returns on time, the manager would praise that person only occasionally. Research demonstrates that intermittent reinforcement tends to take longer than continuous reinforcement to produce acceptable behavior, but the behavior resulting from intermittent reinforcement will last longer and be more resistant to change.

Carol Freedman could try to modify the behavior of both Jorge Lopez and Chuck Simmons. When they argue and disrupt their departments, Carol could respond by giving them the cold-shoulder treatment, or she could take more direct action, such as reprimanding them or putting unfavorable notes in their human resources files. Alternatively, if they improve their relationship, Carol could become friendlier, praise each of them, and place favorable notes in their permanent records. In this way, she would be reinforcing the acceptable behavior (not arguing) and attempting to put a stop to the unacceptable behavior (arguing and disrupting the workplace). Note that in trying to modify her employees’ behavior, Carol Freedman is not attempting to change their personalities or values. Instead, her actions are directed at the particular behavior she does not like—their overt interpersonal conflict.

One last point about behavior modification should be discussed. Many behavioral experts believe that punishment should be used infrequently because it tends to produce undesirable side effects. Employees do not like to be punished, and they look for ways to retaliate, such as leaving their jobs, spreading negative rumors about the manager, and performing only a minimum amount of work. Instead of punishing poor behavior, many experts suggest that managers not respond to it. If an employee behaves correctly, the individual should be rewarded; if not, no reward should be given. In short, punishment should be an option that managers are slow to exercise.

Playing the Role of Mediator and the Art of Image Exchanging

In interpersonal conflict, people are very aware of what they dislike about each other. If asked to prove the other person is at fault, they probably could specify the offending acts and when they occurred. Yet these people are surprisingly unaware of their own contribution to the conflict.

Image exchanging is a behavioral technique used to reveal the perceptions of each side in a conflict. The core of this technique is the exchange of perceptions, or images, about the people engaged in the conflict. Images are impressions and representations about yourself or others. Image exchanging is one of the tools often used by skilled mediators—as mediation generally begins by clarifying perceptions, which lays the foundation for defining the needs of the conflicting parties and of the eventual generating of options that might meet these needs. The specific steps involved in image exchanging are laid out as part of Tool 4–5.

Conflict Resolution Tool Box

Conflict Resolution Tool Box

Tool 4–5 The Art of Image Exchanging

At first, image exchanging may seem an awkward approach for many managers. With practice, however, it can become an effective tool in opening the eyes of disputants to how others view them—and thereby can lay the foundation for changing those behaviors that are creating an interpersonal conflict. Here are five key steps for putting this conflict resolution technique into practice.

1. The individuals involved in the conflict describe their own image and that of the other person. These descriptions can be written in sentence form or as a list of adjectives. The descriptions should be honest, but not overly hurtful or rude.

2. The individuals exchange both sets of descriptions.

3. Each person lists the behavior or behaviors that probably led the other person to arrive at these images.

4. The individuals exchange lists.

5. The individuals discuss the written responses and decide how they can reduce the discrepancy between self-image and the image held by the other person. Realistic goals are set to improve the relationship, reduce conflict, and increase cooperation.

Caution: Do not attempt this technique without trying it out on two employees that you know well and who understand and accept the central ideas of it. Most people are not used to expressing their deeply held opinions of coworkers, nor are they used to hearing others express such opinions. The lesson here is that a little bit of honesty can shed a lot of light on an interpersonal conflict.

Adapted from Edgar H. Schein, Process Consultation, Volume I: Its Role in Organization Development, second edition, Addison-Wesley, 1988, pp. 108–109.

To show how image exchanging works, we’ll use this chapter’s case study to demonstrate the process. Suppose Carol Freedman required both of her subordinates to describe themselves and each other. Read what Chuck Simmons wrote:

Self-image: |

Hardworking, conscientious, dependable, quality-oriented, perfectionist, good company man |

Image of Jorge Lopez: |

Loud, crude, hardworking, bad with people, ambitious, stubborn, careless, intelligent, blames others for his mistakes |

Now read what Jorge Lopez wrote:

Self-image: |

Smart, tough, hardworking, ambitious, strong, can-do manager, self-reliant, oriented toward high production, impatient, a real fighter |

Image of Chuck Simmons: |

Slow, sneaky, mean, careful, excellent mechanic, loyal to company and his employees, stubborn, unwilling to change, has old ideas, wants quality above everything else, not promotable |

When they finished writing, both supervisors exchanged their perceptions. You can imagine the jolt they received when each read what the other had written.

Step 3 of the process specifies that each person list the behaviors they think led to the other person’s perceptions. Let’s consider how Chuck and Jorge reacted to each other’s view. First, Chuck Simmons:

Jorge’s image of me is not flattering. I agree that my department is slow, but that’s because I demand quality work. It bothers me that he thinks I’m sneaky and mean. He might think that because I sometimes try to get even with him for embarrassing me in front of my employees. When he does embarrass me, I do slow down and look for other problems with the machines. But that’s my only reaction to Jorge’s yelling. I shouldn’t do it though.

However, Jorge’s image of himself is too flattering. He makes himself sound like a cross between a cowboy and a combat pilot. He’s confusing all the hot air he blows with results he thinks he’s producing for the company. Jorge believes that he’s more important than anything else, and that’s just wrong. By pushing too hard, Jorge not only hurts other people, he hurts the company as well.

Now read what Jorge Lopez had to say:

Chuck’s image of himself is not that far off from his behavior. He’s a slow, careful guy. But he neglected to mention some of his bad traits. Sometimes, you can be too slow and too careful. That’s Chuck’s problem. He thinks these machines belong to him, but they belong to each production supervisor. I want him to repair my machines the way I want them repaired. That means Chuck should do the job faster and be less of a perfectionist. Then he’d really be the company man he thinks he is.

Chuck’s image of me is all wrong. I think he feels I’m selfish and would walk over my grandmother to get ahead. I have morals and principles. I am stubborn and I’m tough with people who don’t do a good job. I know I fly off the handle sometimes, and I know that’s stupid. When I sound like I’m out of control, his image of me is probably right. But that’s not how I am most of the time.

Steps 4 and 5 of image exchanging involve a face-to-face meeting between the conflicting parties to discuss what they have written. Because this meeting could evolve into a rather heated exchange, the manager should be there to act as a referee. However, before assuming this role it is a good idea to consult an HR officer—explaining the situation and how you are handling it. As pointed out in Chapter 1, the rules of due process, as well as many federal and state laws, regulate many aspects of interpersonal relations in today’s workplace. It is likely that you were made aware of these during your training, but unless you’ve been regularly applying this aspect of your training, it is easy to forget or confuse them. By consulting with HR first, you’ll have a chance to review the relevant due-process and legal issues that might be involved, and this will lay the ground rules for what you can and cannot do.

Both Chuck and Jorge are probably disturbed by the other’s opinion. But by meeting, they should be able to reduce the discrepancies between their self-images and the image held by the other person. The meeting should also cover ways to reduce interpersonal conflict in the future.

Image exchanging is not designed to change personality or core values. Instead, it allows those involved to explore perceptions and interpretations of behavior, things that typically lie beneath the surface in the average workplace. When people know how others see them, they can begin to reduce some of their annoying behaviors and, thus, mitigate the possibility of at least some interpersonal conflict.

Metaphorically speaking, image exchanging can open up cans of worms and turn molehills into mountains. It takes an experienced, skilled manager to pull it off. Test the waters tentatively with this technique. If you are going to try it out, do so first on two employees with whom you have had longstanding relationships; explain to them that you are going to use them as guinea pigs for a creative management technique. Make sure the employees understand the procedures and are very receptive to them. Only then should you proceed. Perhaps you will become good at it, and image exchanging will be in your tool box of conflict resolution techniques. But don’t worry if you can’t make it work; you’ve got many other techniques to choose from.

Diffusing Emotions

Interpersonal conflict is difficult to reduce when it’s mixed with anger and hostility. As discussed in Chapter 2, interpersonal conflict is exacerbated by escalating conflict. A particularly nasty word or behavior causes the other side to respond in kind. This in turn spurs the first party to respond with further intensity. This spiral will continue until either the participants or a mediator stops it.

Escalating conflict tends to produce seemingly irrational behavior. Instead of trying to achieve mutual goals, participants focus on getting even with the other side. Ultimately, the desire to get even can be costly for the organization.

There is strong evidence that the interpersonal conflict between Chuck Simmons and Jorge Lopez has evolved into an escalating conflict. Jorge raises his voice at Chuck in front of Chuck’s employees; in response, Chuck purposely prolongs the repair job. This causes Jorge to raise his voice even more. How can Carol Freedman help her supervisors break this spiral? How can she stop this conflict from escalating? The emotional intensity of many interpersonal conflict situations is the key to understanding escalation. As each side is injured by the other side, emotional intensity builds and expands. Diffusing the emotions of the participants can halt the escalation, enabling deescalation to begin.

Carol Freedman could diffuse the emotions of her subordinates through specific procedures and rules. If you recall, Chuck Simmons revealed a critical fact about himself in the image exchanging process. He wrote: “It bothers me that he thinks I’m sneaky and mean. He might think that because I sometimes try to get even with him for embarrassing me in front of my employees. When he does embarrass me, I do slow down and look for other problems with the machines.” (Notice how image exchanging has opened up a new can of worms. Use this technique sparingly!) Chuck Simmons responds to the embarrassment by spending more time than necessary fixing the machinery. Thus, we have a clearly drawn picture of conflict escalation. Carol has to find a way to break the conflict’s spiral. Let’s see how she does it.

It appears that Chuck’s embarrassment at being yelled at in front of his employees is a critical factor in the escalation. Carol establishes the following rule to deal with this issue:

Guys, I’ve just instituted a new rule. No more fighting in front of your employees. If either of you has a problem with the other, go to the locker room or use my office to work it out. I don’t want your employees witnessing arguments between their supervisors. It’s not good for morale.

Carol justifies this rule by noting the negative impact arguing has on the morale of subordinates. Carol didn’t say the rule would de-escalate the conflict or prevent Chuck from retaliating, because both men will respond to it better if they’re not singled out and blamed for the escalation.

Carol also implied that conflict is acceptable and legitimate, as long as it is dealt with properly. Letting off steam can actually reduce conflict, as long as it’s controlled. For example, in their classic book Getting to Yes: Negotiating Agreement Without Giving In (Fisher et al. 1991, 31–32), Roger Fisher, William Ury, and Bruce Patton describe how one steel company’s labor-management group set up a human relations committee to handle evolving interpersonal conflicts before they became serious problems. The committee used an unusual technique to minimize the impact of emotions on conflict. It adopted a rule stating that one and only one person could get angry at a time. This made it legitimate for others not to respond stormily to an angry outburst. It also made expressing anger easier by legitimizing the outburst itself. The rule had the further effect of helping people control their emotions. Breaking the rule implied a loss of self-control and, thus, a loss of face.

One way to diffuse emotions is to channel them so that they occur at the proper time and in the proper place. Managers cannot totally eliminate the emotional reality of interpersonal conflict; nevertheless, they can institute rules and procedures to reduce escalating conflict and keep emotions in their proper place within the interpersonal conflict process.

If a manager sees that an employee needs to let off steam—that is, if the manager sees that the employee has let his or her frustration build to intolerable levels—the best strategy is to find a private place and simply let it happen. Control your urges to interrupt, listen quietly, provide “uh-huhs” to keep the employee talking (these don’t necessarily connote agreement with what is being said), and occasionally prompt the employee to continue until he or she has spoken his or her last word. In this way, you minimize the inflammatory effects of blowing off steam, give angry employees every encouragement to vent all of their feelings, and leave little or no residue to fester.

Another means to diffuse emotions is to inject humor into the situation. Humor is helpful in reframing a conflict situation. The term reframing is taken from the art world. Changing a frame often changes the way a picture looks. The process works in the same manner psychologically. When a situation is reframed, the facts remain the same but are viewed differently. After hearing a pep talk, the glass of water that looked half empty looks half full. Because of its ability to put things into perspective, humor, as Malcolm Kushner puts it in his popular book The Light Touch: How to Use Humor for Business Success (Kushner 1990), provides an important frame for creating new meanings in conflict situations.

Kushner provides many illustrations of how humor can derail escalating emotions. For example, one office worker was frequently late for work. He and his supervisor had had many exchanges over the problem, in the last of which, the supervisor threatened that the worker’s next lateness would be his last. A few days later, when he arrived at 9:35, a palpable tension filled the office. All eyes focused on him as the angry supervisor approached. But before the supervisor could speak, the worker smiled and stuck his hand out: “How do you do,” he said. “I’m applying for a job I understand became available just thirty-five minutes ago. Does the early bird get the worm?” The office exploded in laughter. The natural inclination of someone in the office worker’s position would have been to offer additional excuses. However, that would have placed him in direct conflict with his supervisor. By accepting the assumption that he was fired, the office worker “went with the flow, surprised his supervisor, and kept his job” (Kushner 1990, 113).

![]() Think About It

Think About It

Think about what can escalate and what can diffuse your emotions during an argument or conflict situation. Write your brief responses to each of the following in the space provided.

Think about someone who knows you well, such as a spouse or coworker. If the two of you are coming close to having an argument, list two things that this person might say or do that would make your emotional temperature really rise.

_____________________________________________

_____________________________________________

_____________________________________________

_____________________________________________

Let’s assume when your “hot buttons” are pushed that you sometimes lash back with a hurtful comment or action. Instead of lashing back, what might you do instead? List two tactics that you have found successful in bringing down your emotional temperature, so that your subsequent words and actions aren’t so inflammatory.

_____________________________________________

_____________________________________________

_____________________________________________

_____________________________________________

The whole point of using humor to diffuse emotions when trying to resolve conflict is that you can’t laugh and be angry at the same time. Humor defuses conflicts by changing expectations. In Kushner’s words: “When a conflict is escalating, things seem to be going inexorably in an anticipated direction. But if something completely unexpected happens, then things can’t continue that way and a change must occur” (Kushner 1990, 111–112). When emotions look like they’re getting out of control, say the unexpected—with a smile! You don’t have to be a comic genius.

Kushner also warns us, however, that humor can backfire. It is best used when a manager knows the employees involved, what they might find offensive, and the type of humor that is appropriate for them.

Improving Communication

In analyzing conflict, someone usually makes this remark: “It all boils down to a problem of communication.” This is often true. People fight because they don’t communicate well. Thus, if the communication problem is solved, people will understand each other and, therefore, stop fighting. The reason is that, in many cases, the participants in interpersonal conflict cannot or will not hear what the other side is saying. Both sides feel as if they’re talking to a brick wall. In other cases, poor communication results in faulty attributions— errors concerning the causes behind others’ behavior. As Jerald Greenberg and Robert A. Baron observe in their college textbook Behavior in Organizations, when an individual finds that his or her interests have been thwarted by someone else, he or she often attempts to find out why this other person acted as he or she did. “Was it malevolence—a desire to harm them or give a hard time? Or did the provoker’s actions arise from a source beyond his or her control?” (Greenberg and Baron 1997, 383). When an individual arrives at the first conclusion, resentment and the resulting conflict are very likely to occur; this conclusion is more likely to occur when communication is bad. As management expert Elwood Chapman concludes in his classic book on human relations Your Attitude Is Showing (Chapman 2001), “the lifeblood of good relationships in the workplace is free and open communication,” and effective managers make this one of their most important one of their most important goals.

How can a person deal with significant communication problems? How can both sides in a conflict be sure they’re really hearing what the other side is saying? The answer lies in active listening. Carl Rogers and Richard E. Farson define active listening as the process of hearing and responding to other people in a way that makes it clear you understand and appreciate both the meaning and the feelings behind what others are saying (Rogers and Farson 1977). Tool 4–6 specifies the major elements involved in active listening. Examine it carefully before reading further.

Conflict Resolution Tool Box

Conflict Resolution Tool Box

Tool 4–6 Becoming a Better Communicator Through Active Listening

As discussed in this chapter, better communication can often prevent interpersonal conflict from ever starting, as well as mitigating it once it is under way. The active listening approach stresses that improving communication begins less with talking better and more with listening better. The weak link in communication is, more often than not, receiving information, not sending it. You should use Tool 4–6 in conjunction with Tool 1–2.

1. Listen for total meaning. A statement usually has two components: the actual content and the feeling or attitude underlying the content. Remember that both the content and the feeling are important because they give the message its meaning, and it is the total meaning that the listener has to try to understand.

2. Note all the cues. Remember that not all communication is verbal. Other cues, such as facial expressions, hesitations in speech, and voice inflections, also communicate attitudes. These nonverbal cues can be even more important than verbal communication in conveying a person’s feelings.

3. Don’t act as judge. Passing judgment and giving advice are almost always seen as direct efforts to change a person. They represent exactly those things that you want to avoid as an active listener.

4. Show that you are interested. Listening attentively and trying to understand the total meaning demonstrate that you’re really interested in what the other person is trying to communicate. Also, active listening depends on the listener permitting the speaker to express himself or herself. Repeated interruption will frustrate the speaker and undermine your attempt to understand what that individual is really trying to communicate.

Adapted from Carl Rogers and Richard E. Farson, “Active Listening,” in Carl Anderson and Martin J. Gannon (eds.), Readings in Management, Little, Brown, 1977, pp. 284–303.

As should be clear, Rogers and Farson believe the key to effective communication is not talking more or better but listening better and trying to understand more. Talking less is essential to becoming a better communicator, but the weakest link in the communication process is receiving information, not sending it. Virtually all contemporary approaches to being an effective leader—whether of a team, a department, a division, or an organization—emphasize this point. For example, in the words of Richard Daft and Raymond Noe, authors of Organizational Behavior, a leading textbook in university-level business programs in the United States, “good communication,” so essential for leadership, is less about expressing oneself and more about “learning to listen.” Effective leaders “ask more questions than they answer” (Daft and Noe 2001, 410).

How can Tool 4–6 be applied to our case? Think about the interpersonal conflict between Chuck Simmons and Jorge Lopez. The evidence is not complete, but there appear to be gaps in the way these two men communicate.

Carol Freedman could improve communications between Chuck and Jorge by restructuring their arguments. Recall that their conflict typically ends up in Carol’s office. She could improve communications between them by instituting the following rules:

1. Only one person can talk at any particular time; no interruptions are allowed.

2. The person responding to a remark must be able to paraphrase that remark accurately before attacking it. The person who made the remark determines the accuracy of the paraphrasing.

3. No personal attacks or criticisms are permitted. A person can find fault with someone’s arguments but not with the person. (Recall the first tenet of principled negotiation. See Exhibit 1–4.)

4. If you must criticize someone, criticize yourself.

5. Speak to be understood, not to win points. This is not a debating session.

These rules are based on the active listening steps in Tool 4–6. They are designed to slow down the flow of words and feelings in order to permit better absorption by the other side. While better communication by itself will not normally eliminate interpersonal conflict, it can help to halt escalation of the conflict. Let’s pause here and think about how your communication style might be hurting your relationships (both on and off the job). Please take a few minutes to complete the following Think About It exercise.

![]() Think About It

Think About It

Think about the last two times you got embroiled in an argument with someone close to you—your spouse or partner, a friend, or a coworker. Did you use phrases that escalated the disagreement—turning up the emotion and turning down the probability of a resolution that might satisfy everyone? Here are some examples: “You always . . .”; “Your problem is . . .”; “You don’t know how I feel!” Did you use any of these particular ones? Can you add two other such phrases that you are prone to use in an argument that have the same chilling effect?

_____________________________________________

_____________________________________________

_____________________________________________

_____________________________________________

_____________________________________________

_____________________________________________

_____________________________________________

CONFLICT RESOLUTION IN THE AGE OF ELECTRONIC COMMUNICATION

Electronic communication has transformed organizational work. It allows individuals to communicate asynchronously, thereby allowing them to work at different hours. It brings them together across short and vast distances equally well—and at a fraction of the cost and inconvenience of coming together for face-to-face meetings. It allows political borders and cultural differences to be readily bridged. It allows massive amounts of information to be quickly exchanged and easily stored. It is especially effective in monitoring the status of an issue, sharing information, and floating ideas. However, it is a slippery area when it comes to conflict resolution. Let’s pause here for a few minutes so that you can offer an example from your own life of what we’re talking about.

![]() Think About It

Think About It

Think about a time when you were upset and shot off a poorly conceived e-mail or voice mail in the heat of the moment. Did it come back to haunt you? In what way? If it fortunately did not, how might it have?

_____________________________________________

_____________________________________________

_____________________________________________

_____________________________________________

_____________________________________________

_____________________________________________

When Conflict Resolution by Walking Is Preferable to Electronic Communication

It is not news to most of us that the ease of leaving a voice message or popping off an e-mail can come back to haunt us when what we said was poorly thought out or done in the heat of the moment. (Consider what you just wrote in the preceding Think About It box!) Moreover, academic research on communication processes reveals that electronically mediated interaction can significantly hinder our abilities to resolve conflict because of the loss of subtlety. It is much easier to comprehend the real meaning of another’s words and stance during face-to-face interaction. Not only can voice tone, volume, and cadence be incorporated into our understanding of what the other person is truly trying to say, but body language, facial expressions, and intuitive assessments can help you determine the following:

• Can this person be trusted?

• How uncomfortable is this person with the topic or particular aspects of it?

• Is this person genuinely interested in resolving the conflict?

Trust: As any seasoned negotiator knows, the full nature of any particular conflict can be hard to discern. More often than not, it is only partly about what those involved say it is about. Appearances can be deceiving. Like an iceberg, as much as 90 percent of what is motivating a conflict can be hidden from view. In dealing with any particular conflict in your organization, whether you are directly involved as a participant or whether you’re performing the conflict resolution role of your status as manager or team leader (for example, intervening in a dispute between two individuals in your department or on your team), you need to develop a degree of trust with each party involved. This trust will allow you to draw out the hidden agendas, the often buried and hurt feelings, and the most relevant aspects of the personal histories that are entwined with the conflict at hand.

Trust is a two-way street: As an individual comes to trust you, he or she will come to believe that you’re a decent person and send you that message in a variety of ways (letting his or her guard down; teasing you; beginning to confide in you; asking your opinion; exuding a degree of warmth and respect; inviting you to coffee or lunch; and so on). In turn, you will come to trust him or her—and begin sending that message in the same ways. In their highly praised book The Shadow Negotiation, conflict resolution experts Deborah M. Kolb and Judith Williams observe that “only recently have we become aware of how important the ‘invisible’ work of trust building is to negotiation. Without that effort, a commitment to a joint solution has little opportunity to develop and solutions will remain, in one way or another, dissatisfying” (Kolb and Williams 2000, 185). Kolb’s and Williams’s experiences match our own. And like us, they have found that trust building is a part of the broader process of relationship building that grows best out of face-to-face interaction—over coffee, at lunch, hanging around the watercooler, during strolls around the grounds, doing things together.

Evolutionary psychologists tell us that human beings have evolved to be lazy. Work requires calories; calories require finding food; food is often scarce, so—in the long run—it’s better to burn fewer calories than more; ergo it’s better to be lazy. E-mail, instant messaging, and other forms of electronic communication play into our natural tendency to be lazy. But to be good at the resolution of interpersonal conflict, you have to resist this tendency. More specifically, if you are involved in a brewing conflict—better yet, if you want to reduce the probability of one even beginning to brew (see Chapter 6)—you have to get up and walk down the hall to your coworker’s office, or to the break room, or to the cafeteria. You have to spend time listening, sharing, and learning what makes the other person comfortable. And all of this “takes some effort” (Kolb and Williams 2000, 185).

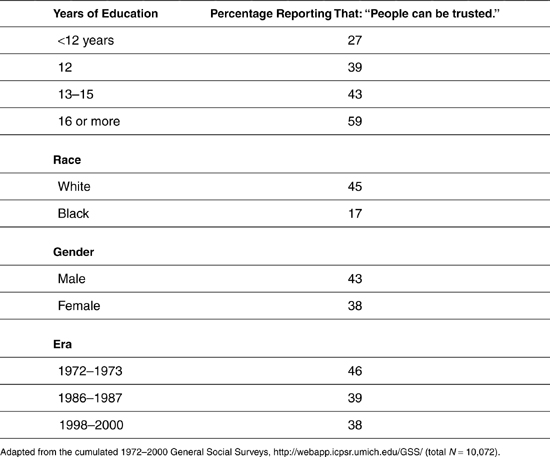

The amount of effort it will take to develop trust with particular coworkers and staff within your organization partly depends on their social position in the larger society. In general, those individuals who have experienced greater social and economic hardship will tend to be more suspicious of human motivation and present greater challenges when trying to build trust. Moreover, a basic lack of trust in all people has been steadily creeping into our society over the past several decades (though the pace of this phenomenon has slowed in recent years). Exhibit 4–1 displays data supporting both of these social facts. The data are taken from the General Social Survey question: “Generally speaking, would you say that most people can be trusted or that you can’t be too careful in dealing with people?” (Recall from Chapter 1 that the General Social Survey is a national probability sample of the U.S. adult population conducted every two years by the National Opinion Research Center at the University of Chicago and that it generates some of the best data that we have on our attitudes toward a wide variety of issues.) There are some strong tendencies in the responses, and these can give you insight into the ease or difficulty you might have in building trust with various individuals in your organization, depending on their social background. The data also need to be put into the context of your own social background in comparison to that of the individual(s) with whom you are trying to resolve a conflict. A basic principle of sociology is that “likes attract.” Thus, two forty-year-old, college-educated, African American men from northern Virginia will have had more similar experiences with life and the world in general than, say, one of these men and a white woman in her late sixties from New England who never finished high school. Social background does not necessarily determine one’s behavior and attitudes, but it does channel them in certain directions. The more you are aware of an individual’s social background, the better your chances of understanding him or her.

![]() Think About It

Think About It

As noted here, as much as 90 percent of what a conflict is about can be hidden from view. Think about the following scene that erupted between administrative assistant Phyllis and Fred, one of 12 sales reps for whom she has clerical responsibility. Use your imagination to come up with what the real conflict is about—what is unspoken here.

Situation: Just before lunch, Fred hands Phyllis a sales contract draft that needs to be typed up and printed out on company stationery. Looking at the contract, and not at Fred, Phyllis curtly responds, “This will have to wait until after lunch, maybe even until tomorrow morning.” “No way!” Fred shoots back in a voice raised to at least three times its normal volume, to which Phyllis replies in a similarly raised voice, “I don’t work just for you!”

Write down what you think might really be going on.

_____________________________________________

_____________________________________________

Comfort level: Sometimes an e-mail or an instant message from one party in a dispute will contain the straightforward statement “I’m not comfortable talking about this,” or “I have difficulty talking about this,” but more commonly this doesn’t happen. Most organizational cultures encourage consensus, being a team player, going with the flow—all of which discourage dissent and the expression of hurt feelings or other forms of uncomfortableness. Electronic communication masks blushing, stammering, cracking voices, twitching faces and bodies, nervous fiddling with objects, smiling, frowning, laughing, crying, and many other cues that reveal the comfort level of the communicator. Some indication of this level can come across during a telephone conversation or a videoconference, but it is generally best apprehended during face-to-face interaction. Our advice, again, is to turn off your computer and put your telephone on hold. Conflict resolution by walking is what we call it. Walk to each of the offices of the disputing parties; walk to the lunchroom and meet each party for a cup of coffee; walk with each of them on the grounds. In short, make time for relationship building—as, ultimately, you will need to not only negotiate the issues involved in a conflict but negotiate with the people themselves (more on this in Chapter 6).

Let’s pause here for a few minutes and connect the present discussion with what you were offered in Tool 4–6. Completing Exercise 4–1 will reinforce the idea of how much is lost when we don’t communicate face-to-face.

![]() Exercise 4–1

Exercise 4–1

As Tool 4–6 points out, it is important to “note all the cues” when trying to become a better listener, thereby becoming better at conflict resolution. Not all communication is verbal. Other cues—such as facial expressions, hesitations in speech, and voice inflections—also communicate attitudes. These nonverbal cues can be even more important than verbal communication in conveying a person’s feelings. Write down at least two of the nonverbal (for example, facial, bodily) cues that you would consider being indicative of the following emotions:

Anger:

_____________________________________________

_____________________________________________

Excitement:

_____________________________________________

_____________________________________________

Being truly interested:

_____________________________________________

_____________________________________________

Lacking interest:

_____________________________________________

_____________________________________________

Heartbreak:

_____________________________________________

_____________________________________________

Interest level: Here’s a shocker for those who’ve learned management from a book rather than from experience: A lot of disputants have no real interest in resolving their conflict—at least in any way that benefits the interests of the other side. This can be a serious problem for a manager or team leader, as more often than not unresolved conflict will end up hurting organizational performance, not to mention the individuals involved. Sometimes the speed at which an e-mail is sent can indicate a disputant’s level of interest in resolving the problem (consider the different reaction you have to a nearly instantaneous response to an e-mail you’ve sent someone versus a response taking days or even weeks). Conflict resolution by walking is once again the best way to find out an individual’s interest in resolving a conflict. If your face-to-face interaction tells you that such interest is minimal, you’ll often find that the root cause is a long and less-than-satisfying relationship between the disputants (which might be an eye-opener if you are one of them). If you’re trying to help resolve a conflict between two of your staff or team members, it’s likely that you will have to talk with their coworkers about the disputants’ relationship. This is something that should be done in private conversation, sometimes by phone but almost never via e-mail.

In sum, be cautious and judicious with your use of electronic communication in conflict resolution. As a general rule, reserve nuanced discussion, consensus building, and decision making for face-to-face meetings, or when this is not possible, at least save these techniques for the telephone or a teleconference (if that technology is available to you).

When Electronic Communication Is More Appropriate Than Conflict Resolution by Walking

There are some obvious benefits to e-mail, Web-based discussion, and instant messaging: ease, efficiency, and economy. Conflict resolution by walking sometimes involves driving a car from one company location to another, but as the physical distance increases between you and those with whom you’re involved in the resolution of conflict, its usefulness declines. In an era when teams are created using individuals who are working great distances—sometimes even hemispheres—apart, managers must have the capacity to do their negotiations and conflict resolution work via the telephone and electronic communication. Moreover, there are some aspects of electronic communication that are universally useful for conflict resolution. Indeed, if used wisely, electronic communication can actually sidestep the miscommunication that can occur in face-to-face communication and through this—as well as a variety of other means—maximize the probability of a successful resolution.

Many mediators have found that the asynchronous nature of electronic communication can enhance conflict resolution, whether the participants are continents apart or right down the hall from one another. Asynchrony offers individuals the time to contemplate their responses to one another, allowing for less emotional, more rational, finely crafted discourse. In complex cases, or in those involving a higher-level form of ADR such as mediation, it is often so difficult to schedule enough meetings that there arises strong pressure to resolve the conflict too hastily—on the spot while everyone is present. This often results in falling short of the best resolution for the conflict at hand. Long-time professional mediator James Melamed expresses his preference for electronic communication when he observes, “Face-to-face mediation often becomes ‘crisis’ like, commonly limited to a single tense meeting. The Internet, by contrast, allows participants, lawyers, and the mediator to move beyond crisis mediation to more capable and relaxed asynchronous problem-solving discussions” (Melamed 2000, 4).

The guidelines of good oral communication generally apply to good written communication within the organization (e-mails, memos, announcements, bulletin board items)—that is, being nonjudgmental and displaying interest in others’ concerns. With these as a foundation, we have found over the years that electronic communication—e-mail, threaded discussions (conducted via listservs), and other forms of Web-based discussion—can assist you in your conflict resolution efforts in the following ways, most of which arise out of its asynchronous nature:

• Setting up meeting times.

• Sharing data.

• Laying out possible ways in which an issue might be viewed—which can often be done more thoughtfully and more completely when a person is not under the emotional stress often involved in face-to-face interactions. Because anything you put into writing can quickly—and repeatedly—come back to haunt you, couch your language in the subjunctive mood: “What if we considered this possibility...what do you think would be the consequences?” “Let’s say we were to try doing this, what do you think might happen?” Again, following the rules of good oral communication are essential.

• Drafting and refining language for documents.

• Archiving data discussions. This is especially helpful when the conflict resolution process is going to take a long time. It is also useful in getting newcomers rapidly caught up.

• Establishing links to Web materials relevant to the conflict; like archiving, this is also useful in getting newcomers quickly up to speed.

• Participating in ODR (online dispute resolution). There are a growing number of companies specializing in doing ADR via the Web to resolve conflicts between businesses and their customers and between individuals or groups within an organization (for a list of these companies, see Vincent Bonnet, et al., Electronic Communication Issues Related to Online Dispute Resolutions; available online at www2002.org/CDROM/alternate/676/index.html). For reasons of cost saving and convenience, ADR already commonly involves the use of e-mail and the Web, but ODR takes this to the utmost and completely eliminates face-to-face meetings. ODR is an outgrowth of e-commerce and has grown at the same astonishing rate. It was originally developed—and is still most often used—for disputes between businesses and their customers involving dealings over the Web. The traditional business transaction issues of misquoted prices, poor quality, mis-represented specifications, and late deliveries dominate ODR. ODR is the electronic form of ADR, and there is an ODR equivalent for each of the forms of ADR described in Chapter 2. There are a large number of security and legal issues surrounding the use of ODR that go far beyond the scope of this course (for more information, consult the Bonnet reference), but our key recommendation would be to use the ODR services of a firm that is well established and reputable in traditional, face-to-face ADR—for example Triple A (American Arbitration Association) or NAM (National Arbitration and Mediation association). Among the services of such firms are videoconferencing, teleconferencing, instant messaging, message posting (threaded discussion), and e-mail organizing and tracking systems.

There is much to recommend the use of electronic communication in the resolution of conflict—particularly when the discussions are complex and would benefit from the asynchrony. When your team members, coworkers, or subordinates are separated by great distances, you will by necessity have to rely more on e-mail and the Web. Nevertheless, our general advice still stands: Be judicious in your use of electronic communications and, whenever possible, save decision making and final resolutions for face-to-face meetings. And when this is not possible because of great distance, then use videoconferencing, teleconferencing, or the telephone—depending on the number of individuals involved and the technology available to you.

Creating Superordinate Goals

Let’s now return to the Chuck and Jorge scenario as we introduce superordinate roles. If Chuck and Jorge are furiously arguing with each other and the plant catches on fire, what will happen to their argument? Obviously, it will be postponed as both men try to save their own lives. If a fire door is stuck and one man alone is not strong enough to budge it, Chuck and Jorge surely will cooperate to open the door. These goals are much more important than the argument involving maintenance, at least in the short run. Naturally, managers will use less dramatic superordinate goals to resolve interpersonal conflicts between subordinates.

A superordinate goal is a goal that is highly desired by each party but one which cannot be attained by either party acting alone. A memorable example of the power of superordinate goals to resolve conflict was provided by Muzafer Sherif and his colleagues in their study of boys attending a summer camp. The fundamental hypothesis of Sherif and his colleagues was that “when two groups have conflicting aims (i.e., when one can achieve its end only at the expense of the other) their members will become hostile to each other even though the groups are composed of normal, well-adjusted individuals” (Sherif 1988). To test this hypothesis, the researchers produced friction between two groups of boys by having them compete against each other in a series of games, including baseball, touch football, tug-of-war, and a treasure hunt. He discovered that, although the games started in a spirit of good sportsmanship, this good feeling evaporated quickly as the games progressed.

The groups began to refer to each other as “sneaks” and “cheaters.” The individual members refused to have anything to do with those on the opposing side, and the boys frequently turned against their friends if they were in the other group. In one incident, a group burned a banner left behind by the opposing team only to have its own banner seized the next morning. Name-calling, scuffles, and raids were common. Solidarity increased within each group, and there were leadership changes as well. One group removed its leader because in a contest he couldn’t “stand up” to his adversary. Another group made a hero out of a boy who had previously been regarded as a bully.

Sherif and his colleagues then hypothesized that “just as competition generates friction, working in a common endeavor should promote harmony.” To prove this hypothesis, they created a series of “urgent and natural” situations that required the competing groups to work together to accomplish superordinate goals. On one occasion, the researchers rigged a breakdown in the pipeline supplying water to the camp. They called the boys together and told them about the crisis; both groups promptly volunteered to search the waterline for the trouble. The two groups worked together harmoniously, and before long, they had located and corrected the difficulty. On another occasion, the two groups were taking a trip some distance from the camp. A truck was supposed to be sent back for food, but it wouldn’t start—a situation arranged by the researchers. The boys got a rope, attached it to the truck, and pulled together to start it. The researchers found, however, that joint efforts did not eliminate hostility immediately: