3

Resolution of Structural Conflict

Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter, you should be able to:

• Define organizational structure.

• Explain the seven basic approaches useful in resolving structural conflict.

• Specify at least one advantage of each resolution approach.

• Specify at least one disadvantage of each resolution approach.

INTRODUCTION

In Chapters 1 and 2, we defined terms, developed models, and categorized conflict into various types. We are now ready to explore conflict resolution methods more fully, indicating those situations in which the approaches will be most useful. In this chapter, we will examine the resolution of structural conflict. An organization without any structural conflict does not exist.

KONRAD ZED PERIPHERALS INCORPORATED: A CASE STUDY

As in other chapters, we will illustrate the concepts and principles presented here through incidents and case histories. We’re going to analyze structural conflict and its resolution through a case history involving Konrad Zed Peripherals Incorporated (KZPI), a small high-tech firm supplying sophisticated components to the computer industry. KZPI is housed in a small manufacturing facility that is shared by the engineering staff, the production personnel, and the data entry group.

The engineers at KZPI are a creative, highly educated group of professionals and are supervised by Dr. Ben Chang. Dr. Chang has a Ph.D. in electrical engineering from a major midwestern university. He is an expert in his field and has designed many new products. Three other engineers work with him, and each has a master’s degree in some engineering specialty.

The production area is directed by Larry Sossner, a highly experienced individual. Larry has worked in production for over thirty years, compiling an excellent record for high-quality, rapid-production results. Although he does not have a college degree, Larry Sossner believes that his experience is equivalent to a master’s degree and is fond of sharing his thoughts on this issue as frequently as possible.

Both Ben Chang and Larry Sossner report to Hector Flores, the plant manager. As one of the founders of KZPI, Hector owns about 10 percent of the firm. Unlike most of the employees he supervises, Hector has no engineering or production background. His primary focus is on finances, even though he is able to assimilate the technical reports supplied by his employees accurately and quickly.

The organization has formal lines of authority, shown in Exhibit 3–1. This chart is referred to only when questions involving authority and responsibility arise.

The first hint of trouble occurred when Larry Sossner made an appointment to talk with Hector Flores. Because KZPI is a fairly informal place, Hector suspected that a formal appointment meant something serious. He was right. Part of their conversation follows:

HECTOR: |

Larry, I can tell by the way you look that you’ve got a problem. Out with it! No sense sitting there looking glum. |

LARRY: |

Hector, you can always tell when I’m upset. I really hate to bring this up—it sounds so petty—but it’s serious to me. |

HECTOR: |

No more suspense, Larry. What is it? |

LARRY: |

I’m having a little problem with Ben. It involves the data entry group. I always thought everyone was supposed to have equal access to the data entry keyers. But Ben treats them like they’re his own private assistants. He’s always giving them tons of work and if he wants something right away, he pushes his job to the top of the line. The result is that I’m not getting my data entry done as quickly as I need it. It’s a real problem. |

HECTOR: |

Have you talked to Ben about this? |

LARRY: |

Sure. But he just laughed and treated it like some kind of joke. He hasn’t made any changes, and I still have the problem. |

HECTOR: |

How about my administrative assistant, Marge? She’s in charge of the data entry keyers. Did you talk to her? |

LARRY: |

I tried that, too. But I think she’s afraid of Ben. She told me to talk to you. I don’t think she wants to get in the middle. |

HECTOR: |

So that leaves me, I guess. What would you like me to do? Talk to Ben? |

LARRY: |

I really don’t know. I was hoping you could come up with some good ideas. I don’t want a big fight with Ben, but this problem’s got to be resolved—and soon. |

Keeping this interaction in mind, complete the following Think About It exercise before you continue reading.

![]() Think About It

Think About It

Think about the brewing conflict between Larry and Ben. Why is it a good example of structural conflict? Write down your reasoning here.

_____________________________________________

_____________________________________________

_____________________________________________

_____________________________________________

_____________________________________________

_____________________________________________

ORGANIZATIONAL STRUCTURE

Organizational structure comprises the various jobs and departments existing in an organization and the relationships among them; we can visualize it by using an organizational chart (see, for example, Exhibit 3–1). We’ve said that structural conflict is rooted in the very nature of organizations, and we emphasized that it is magnified by competition for scarce resources, competitive reward systems, interdependence among work units, power differentials, and ambiguity over responsibilities and jurisdictions. The conflict depicted in our case arises from two departments sharing a common resource, the data entry group. In short, the engineering and production departments are competing over a scarce resource.

The differentiation in the organization’s structure, made partially visible through the organization chart, is another way to view the conflict between engineering and production (though the personalities of Ben Chang and Larry Sossner cannot be ignored). If the relationship between the two departments did not include sharing the data entry group, this particular conflict would not exist.

STRUCTURAL RESOLUTION APPROACHES

Hector Flores, the plant manager, has been drawn into the conflict and will probably act either as a mediator/problem solver or as a judge. Because he is in a superior position, Hector has the authority to resolve the conflict himself. Let’s discuss possible conflict resolution techniques.

Using Authority

Hector Flores could use the direct power of his office, his authority (see Exhibit 2–1), to resolve the conflict. By issuing a direct order, the conflict would be resolved, at least temporarily. Consider this possible conversation with Ben Chang, the engineering supervisor:

HECTOR: |

Ben, I hear you and Larry are having some problems sharing the data entry group. |

BEN: |

I don’t have any problems, Hector. |

HECTOR: |

Well, Larry has some. I’ve instituted a new procedure over there. Marge and the data entry keyers have been told to spend half their time doing your work and half doing Larry’s. Also, they’ve received strict orders to work on a first-come, first-served basis. No more rush jobs allowed. |

BEN: |

This is a joke, isn’t it, Hector? |

HECTOR: |

No joke. I don’t have time to fool around with this kind of thing. We have more important things to do. Consider the problem solved. |

There is a certain elegant simplicity about using your authority to resolve structural conflict. Management professor Ross Stagner conducted a study of top executives and discovered that the most popular method of resolving conflict was the use of authority (Stagner 1969). Further, he found that conflicts were usually not resolved on the basis of logical arguments. Instead, most disputes were resolved by resorting to superior power—power based on things such as the ability to provide rewards and dispense punishments.

The primary advantage of using authority is that it’s quick; little time is lost. The primary disadvantage is that more substantial issues may be neglected and the conflict may arise again later. Moreover, subordinates who have not been allowed to fully air their grievances and have input into the resolution of their problems are likely to feel resentment, which can crop up unexpectedly and in situations managers might not be able to predict.

Expanding Resources

Because many structural conflicts involve the use of scarce resources, one resolution approach is to expand resources. In our case, Hector Flores might determine whether the data entry group is staffed adequately for the volume of work coming from engineering and production. If not, perhaps hiring another data entry keyer to handle the heavier workload would solve the problem. (Recall the problem between Jack, the salesman, and Phyllis, the administrative assistant, presented in Chapter 1.)

Jay R. Galbraith, a well-known organizational researcher associated with the Center for Effective Organizations at the University of Southern California, has proposed that complex organizations build in extra resources, or organizational slack, to avoid conflict among departments (Galbraith 2001). But while increasing resources appears to be a simple, workable approach to resolving structural conflict, it is not popular, particularly during bad economic periods. Another word for slack is fat, and organizations that are fat are less efficient and find it difficult to compete with leaner competitors. Thus, the disadvantage of this approach to conflict resolution is that it may cost too much, in spite of the obvious benefits. (Recall that this was Jack’s point in Chapter 1 when he had the dispute with Phyllis.)

Reducing Interaction

Remember the old line “It takes two to tango”? That saying accurately summarizes one condition that promotes conflict. If contact between two individuals or groups is eliminated, conflict will disappear. Neither side will have the face-to-face opportunity to negatively affect what the other cares about. For example, Hector Flores might consider eliminating the shared resource. Instead of a data entry group, data entry keyers could be assigned permanently to each department. Thus, both the engineers and the production people would have their own data entry keyer—a simple solution to a simple problem.

However, Hector probably had good reasons for establishing a data entry group in the first place. Maybe he felt that Marge Davis could supervise the data entry keyers better than the engineering and production supervisors. Perhaps he wanted full utilization of both data entry keyers, something he thought would not happen if they were assigned to individual departments.

In addition, there may have been cost considerations. Suppose the engineers needed only a data entry keyer and a half, and the production people needed only a half data entry keyer. Because a data entry keyer cannot be divided in half, this would probably mean that engineering would get two data entry keyers and production would get one. This alternative structure would compel the company to hire another data entry keyer, adding to costs. Further, all three data entry keyers would not be working as hard, simply because there would not be enough work to go around.

So, while eliminating a common resource might appear to be a simple answer, there are costs involved—the major one being the cost of increasing the data entry staff. If Hector Flores is willing to pay that cost, he could resolve the conflict between the two departments by removing the source of the problem—the shared resource—and thus reduce the interaction between them.

Clarifying Job Responsibilities

Let’s complicate the case a bit. Suppose Ben Chang, the engineering supervisor, made an appointment with Hector to talk about a problem he was having with production. The following conversation between the two men describes what the new conflict is all about:

HECTOR: |

Ben, you said you wanted to talk to me privately about something. Any problems with the A-103 design? |

BEN: |

I don’t have any problems with it. But Larry Sossner and his supervisors seem to have a problem. |

HECTOR: |

I don’t understand. They’re not involved in the design. |

BEN: |

That’s exactly the point I tried to make. Those production hotshots have been modifying our designs, and I don’t like it. And my engineers don’t like it, either. We’re the thinkers, the designers, and the production guys should follow our orders. |

HECTOR: |

What kinds of changes are they making? Are they big? Do they add anything worthwhile? |

BEN: |

Oh, all their changes have been small. And sometimes their ideas are good. But that’s not the point. We’re the designers. We have the engineering degrees. If those production people with their high school diplomas can modify our designs, then what’s the purpose of all our education? It just doesn’t make sense. |

HECTOR: |

What do you want me to do? |

BEN: |

Order them to stop messing around with our designs! Make sure they do their job and not ours! That’ll solve the problem. |

Some managers complain about all the bureaucratic red tape and silly rules their organizations generate. But when a jurisdictional squabble occurs, they tend to be the loudest in demanding the institution of new rules. “There ought to be a law!” becomes their battle cry if some other manager or department steps on their organizational toes. Ben Chang, who usually decries all these “foolish” rules, is now advocating another rule. He wants his boss to forbid the production department to do any design work. According to Chang, the lines around those boxes on the organizational chart should be barriers.

The structural conflict between production and engineering is greater in this new example because it involves the responsibilities of the two departments. Hector Flores could resolve the conflict by clarifying job responsibilities more precisely. For example, he could tell production not to meddle in the design area. Rules and regulations, the hallmarks of a bureaucratic system, could be instituted to squash this budding structural conflict. Or, like the supermarket executive quoted in Chapter 2, Hector might view this as constructive structural conflict. He might welcome argument and debate over new designs because, at the very least, it demonstrates the absence of apathy and stagnation within the organization. But let’s suppose Hector views this structural conflict as being potentially very destructive. By precisely defining the responsibilities of each department, he could eliminate the structural conflict. In that event, engineering would design and production would create prototypes based exactly on that design. The problem would be solved, but there would also be more rules and procedures.

Reducing Interdependence

Logically, changing the structure of the organization might minimize or eliminate some structural conflict. The elimination of the data entry group is an example of a possible structural change. But the structural conflict involving departmental responsibilities is potentially much more serious because it forces an examination of what the departments actually do and how their functions interrelate. What are engineering and production really supposed to accomplish? How does the work of one department influence the other? And how does work flow between departments? These are the questions normally asked when major jurisdictional disputes develop. To better comprehend the structural variations involved, examine the interdependencies displayed in Exhibit 3–2.

Interdependence refers to a mutual reliance between two or more parties. I am dependent in some fashion on you; you are dependent in some fashion on me. In organizations, jobs and departments can be mutually dependent. Four different levels of interdependence can exist within modern organizations, ranging from the least interdependent (pooled) to the most interdependent (team). As the level of interdependence increases, the probability that structural conflict will occur also increases.

Pooled interdependence occurs when two or more jobs or departments contribute to and are supported by the same organization, but have no other significant relationship or connection. Exhibit 3–2 offers the example of a fast-food chain. How dependent are various fast-food outlets on each other? Not very. An outlet on the south side of a particular city has little connection with one on the north side. Their relationship can be characterized as pooled interdependence. They belong to the same organization and contribute to overall profits, perhaps they even rely on the same citywide advertising campaign to attract customers, but they have very little, if any, direct effect on each other. Because there is no direct mutual dependence, it is unlikely that structural conflict will develop between the managers of these outlets—at least as it relates to interdependence.

Sequential interdependence is when one job or department is much more dependent on another job or department than the reverse. Department A really depends on Department B, but Department B is not very dependent on Department A. This type of interdependence can lead to significant structural conflict. Referring to Exhibit 3–2, the arrow between the purchasing and production departments represents the flow of work and raw materials. Purchasing must buy the highest-quality raw materials at a competitive price from suppliers. It then sends these raw materials to the production department to use in the manufacturing process. Production is very dependent on purchasing. If purchasing performs poorly, production may receive low-quality materials at too high a price. This may negatively affect the price and durability of the finished product.

From our example, it can be seen that the opposite relationship does not exist. If the production department does a poor job, it will not directly harm purchasing. But purchasing will be hurt indirectly if sales and profits drop considerably as a result of production’s poor performance. We can also say that production failures will directly affect the sales department. Thus, there could be a similar sequential interdependence between production and sales, with sales being more dependent on production than the reverse.

Sequential interdependencies are less common in contemporary organizations than other types of interdependence. This is because the recipient of poor-quality work will usually try to change the relationship to one of more mutual interdependence. Thus, production may refuse to accept poor-quality raw materials from purchasing; sales will return defective products to production for repair. Such retaliatory action will intensify the structural conflict between the departments.

Reciprocal interdependence occurs when jobs or departments supply each other with work. The output of Department A becomes the input for Department B and vice versa. There is a two-way relationship between jobs or departments. For example, airline companies have both operations and maintenance units. Operations provides maintenance to airplanes in need of it, and maintenance provides serviceable aircraft for operations. Airline pilots provide one way to visualize the strong mutual dependence between the maintenance department and the operations department. If the maintenance people don’t do their jobs, the pilots will be flying poorly maintained, potentially dangerous aircraft. If the pilots abuse their aircraft or neglect to report minor maintenance problems, the service mechanics may end up with unusually difficult service problems (Thompson 2003).

Because both departments are highly dependent on one another, the potential for structural conflict is high. Imagine an argument over braking procedures. If there are many ways to brake an aircraft, the maintenance department would probably favor the procedure that causes the least amount of brake wear. The pilots, however, might favor a technique that results in much greater brake wear, if, for example, it was very easy to use compared to other techniques. Because both groups are so dependent on one another, such a disagreement could develop into a major conflict.

Team interdependence occurs when work is conducted jointly on the same product or project at the same time by two or more departments, not simply transferred back and forth between departments. In Exhibit 3–2, you’ll notice that there are five departments involved in a project of some sort: purchasing, market research, engineering, production, and human resources. Let’s assume these departments are collaborating on a new state-of-the-art technical product. Purchasing is there to recommend high-quality, low-cost components; market research provides information on the size of the market; engineering designs the product; production must eventually manufacture the product; and human resources must hire additional engineers and technical people if sales are brisk. The development of this new technical product involves many departments that are highly dependent on one another to accomplish their goals. Because of this complex and deep interdependence, the potential for structural conflict is highest in a situation involving team interdependence.

Modern organizations contain many examples of team interdependence. A top-management team writing a strategic planning document, a hospital operating room team removing an appendix, and a new-product team designing an innovative prototype are all excellent examples of team interdependence. These projects demand that representatives from various departments be included in order to meet the needs of the organization or the customer. (If the bulk of your work occurs in a team setting, most of the techniques of this course will be applicable; however, you should still consult other sources for handling some of the special nuances of conflict resolution in teams, including the American Management Association’s self-study course Making Teams Work. We also recommend Deborah Harrington-Mackin, The Team Building Tool Kit (AMACOM, 1993); Howard M. Guttman, When Goliaths Clash (AMACOM, 2003); Jon R. Katzenbach and Douglas K. Smith, The Wisdom of Teams (HarperBusiness, 2003); and Harvey A. Robbins and Michael Finley, The New Why Teams Don’t Work (Berrett-Koehler, 2000).

Often, it’s possible to change interdependent relationships to resolve conflict. Let’s consider how we might do this in the KZPI example that we have developed regarding Ben’s (engineering) and Larry’s (production) brewing conflict over design modifications. Please take a few minutes to complete the following Think About It exercise before reading any further.

![]() Think About It

Think About It

Reexamine the descriptions of the four types of interdependence in Exhibit 3–2. Then, in the space below, identify the type of interdependence that exists between the engineering and production departments at KZPI.

_____________________________________________

_____________________________________________

_____________________________________________

_____________________________________________

_____________________________________________

_____________________________________________

If you answered that the type of interdependence depends on your perspective, you are correct. In fact, there appears to be a fundamental disagreement between engineering and production revolving around different perceptions of their interdependence. By modifying the designs, production is acting as if the relationship is one of reciprocal interdependence, in which both departments supply each other with inputs. The production department’s design modifications become additional inputs for the engineering department to consider in the development of new products.

In his protest to Hector Flores, the engineering supervisor rejects reciprocal interdependence and requests that Hector reestablish the “correct” relationship. To Ben, this is sequential interdependence, a one-way relationship between engineering and production, whereby engineering supplies production with inputs, but production does not supply engineering with inputs. To quote Ben Chang: “Order them to stop messing around with our designs! Make sure they do their job and not ours! That’ll solve the problem.”

If Hector Flores accepts Ben’s request, sequential interdependence would be established. Because this is a lower form of interdependence, it would reduce the structural conflict. Production would be ordered not to modify the designs in the future, satisfying engineering, but production would probably react negatively. Nevertheless, in the long run, sequential interdependence would lead to less structural conflict than would reciprocal interdependence.

Pooled interdependence could reduce the interdependence between departments even more. Reexamine Exhibit 3–2 before proceeding.

By creating pooled interdependence, the two departments would have very little contact and interaction and would be connected only by their presence in the same organization. Suppose the following conversation took place between Hector Flores and Ben Chang:

HECTOR: |

Ben, I have a question. How much time does production spend building your prototypes? |

BEN: |

Not much. Otherwise, they wouldn’t have the opportunity to play around with our designs. |

HECTOR: |

I have an idea. Why don’t you go out and hire yourself a top production engineer? Have that person work in engineering and report directly to you. That way, you could control the prototype production of your design work. |

BEN: |

Great idea! That would solve all my problems. The production person would do what I want and not go off on some crazy tangent. And I wouldn’t have to fight with the production department anymore. Why didn’t I think of that first? |

This approach significantly reduces the interdependence between engineering and production. Clearly, it would resolve the structural conflict over engineering designs. Nevertheless, as with the expansion of the data entry group or the assignment of data entry keyers to each supervisor, there’s a catch: It’s going to cost the organization more money for the new production engineer. But the costs may be even higher because engineering may be forced to buy new tools and machinery for the new production position.

In sum, reducing the interdependence between two individuals, departments, or teams is one major approach to resolving structural conflict. This approach may be effective, but adopting it will probably mean added costs, so you must be sure the benefits outweigh the increased costs.

![]() Think About It

Think About It

Describe a budding or existing conflict in your organization that is rooted in interdependence (between individuals, departments, or teams). What might be done to reduce this interdependence and thus the conflict? What would be the possible disadvantages of this approach?

_____________________________________________

_____________________________________________

_____________________________________________

_____________________________________________

_____________________________________________

_____________________________________________

Creating Integrators

Creating integrating positions is another technique that can be used to resolve structural conflict. This approach provides us with an opportunity to explore the concepts of differentiation and integration, as developed by Lawrence and Lorsch in their landmark study of the plastics, food, and container industries (Lawrence and Lorsch 1986). Lawrence and Lorsch discovered that division of labor in organizations means much more than people doing different jobs. Not only do people in diverse jobs perform diverse tasks, but they also tend to think, react, relate, and speak differently. In the language of modern organizational theory, they have different cultures. These different cultures make it difficult at times for departments to appreciate or even understand each other. For example, a production department may be oriented to short-term goals, evaluated on cost reduction, concerned more about results than human relations, and accustomed to simple terminology. However, an engineering department may be oriented to long-term goals, evaluated on creativity more than efficiency, concerned more about human relations than immediate tangible results, and accustomed to complex scientific jargon. Under these conditions, it should not be surprising if the two departments do not even understand, much less appreciate, each other.

Now suppose engineering and production have to interact. The design that engineering created needs to be executed by the production department. How will they be able to deal with each other successfully? How can they avoid significant structural conflict? The answer is through integration devices, which are specific positions and structures designed to coordinate dissimilar departments.

In their study, Lawrence and Lorsch discovered that many successful organizations used special integrating devices to bridge the gap between highly differentiated departments. One such device is an integrating position— as represented by a person who works mainly in Department A but reports to a manager in Department B. The major job of the integrator is to help the two departments interact better, in spite of the considerable differences between them. An example of an integrating position is that of purchase engineer, described in the following passage from Henry Mintzberg’s classic work, The Structuring of Organizations (Mintzberg 1979):

Some purchasing departments send out what are, in effect, ambassadors to other departments. They may appoint purchase engineers, specialists who report administratively to purchasing but spend most of their time in the engineering department. Their job is to be instantly available to provide information to engineers whenever they need help in choosing components. They assist in writing specifications [thus making them more realistic and readable] and help expedite delivery of laboratory supplies and material for prototype models. Through making themselves useful, purchase engineers acquire influence and are able to introduce the purchasing point of view before the “completion barrier” makes this difficult.

If a purchase engineer can bridge the gap between purchasing and engineering, a production engineer might be able to play a similar role at KZPI. Consider the following conversation at a meeting between Hector Flores and his engineering and production supervisors, Ben Chang and Larry Sossner:

HECTOR: |

I’ve thought about the problems your two departments are having. Hiring a production engineer only for the engineering department is too expensive. And the production people do have pretty good design ideas, especially one of the production supervisors, Judy Walsh. I propose we give Judy a new job. She’ll be our production specialist. |

LARRY: |

Nice job title, Hector. But what’ll she do? |

HECTOR: |

I want her to spend about 75 percent of her time helping the engineers with the production aspects of their designs. |

BEN: |

I don’t want anybody telling us what to do! |

HECTOR: |

Don’t worry, Ben. She’ll just be a resource, that’s all. I checked her human resources file and she’s six credits shy of a college degree in engineering. She’s taken most of these courses in the evening, so she knows something about engineering. She’s an A student as well, I should add. |

LARRY: |

Yes, Judy’s bright. But I’ve got to replace her in some way. She’s my best supervisor. |

HECTOR: |

You can hire another one, Larry. The rest of Judy’s time will be spent in the production area making sure your people are getting the prototypes right. She’ll still report to you, Larry. |

BEN: |

I’m not sure I like all of this, Hector. But you couldn’t have picked a better person for the position. She’s a good one. |

LARRY: |

I agree. You know what I think of a lot of education without real experience. But Judy has both. I’ll go along with it, too, Hector. Let’s see if Judy can help us improve our relationship. |

Of course, the global issue here is not about the specific problem of integrating production and engineering—we could have developed an equivalent example using a sales engineer to ease relationships between sales and engineering, or a research and development engineer/scientist to serve as integrator between production and marketing. Rather, the point is to think about how you might resolve conflict by creating an integrating position or an integrating role to counteract needless conflict (and, actually, any seemingly needless inefficiency) rooted in differentiation between areas or functions in an organization. The integrator may hold a full-time position or serve this role only on a part-time basis. The integrator may be smoothing relationships within or between or among teams, task forces, departments, or any functionally different units of your organization.

An integrator, such as the production specialist described here, must understand the cultures of both departments—that is, he or she must be able to understand the needs and concerns of both and speak their languages as well. To acquire credibility, Judy Walsh must be a fairly good engineer as well as a production expert. To be effective, she must walk a tightrope between both departments. If she knows enough about engineering and production to impress the employees in both areas, she’ll have a good chance of reducing the structural conflict.

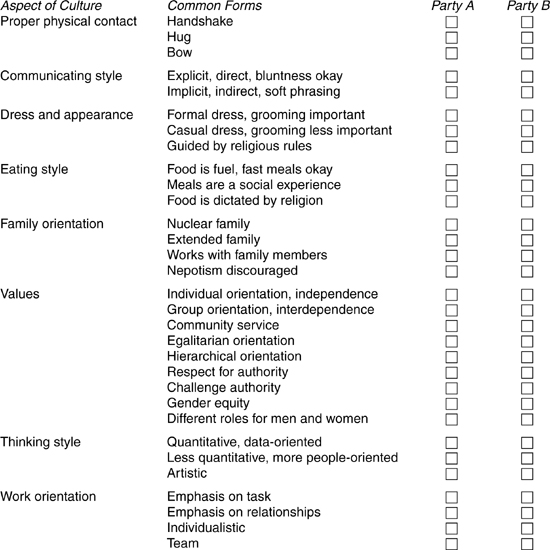

Creating an integrating position or role is not a risk- or cost-free proposition. Nevertheless, it has helped many organizations reduce structural conflict between distinct but closely linked departments. Depending on the needs of your department, team, or organization, as well as on your personality, you may want to develop your own personal abilities at playing the role of integrator (even if this role is never formally recognized in the organizational chart). Cultural differences can be rooted in differences in functional tasks performed by the individual, department, or team; or they might be rooted in social class, race, ethnic, nationality, or gender differences. Whatever their source, whatever your challenge, there are a relatively small number of cultural aspects that you need to focus on. Tool 3–1 will get you started.

Using Principled Negotiation

Recall the discussion in Chapter 1 of the principled negotiation model for conflict resolution. This model emphasizes that conflict reduction is best handled through collaboration and negotiation. Major determinants of successful conflict resolution in this model include separating people from issues, focusing on interests rather than positions, inventing options for mutual gain, and using objective standards. One must also have alternatives to resolving the conflict, knowledge, and the willingness to communicate. (You may want to quickly review Exhibit 1–4.)

Mary P. Rowe, a conflict resolution specialist from MIT, argues that inventing options for mutual gain is the most important tenet of principled negotiation when applying it to either structural or interpersonal conflict (Rowe 1993). In her many years of consulting, Rowe has found that managers are drawn into many conflicts by people coming into their office with a specific complaint, as depicted in our KZPI examples. The most effective managers are slow to use their authority and quick to involve the complaining party in the resolution of the conflict. Rowe’s experience has taught her that there is seldom a single best solution to a complainant’s concerns (as we discovered in our KZPI example), and that those solutions that are developed with the active participation of the complainant tend to last the longest and have the fewest undesirable side effects, such as resentment. Resentment undermines worker satisfaction and productivity; it’s a common result of using too much authority too soon to resolve a dispute.

Conflict Resolution Tool Box

Conflict Resolution Tool Box

Tool 3–1 Developing Your Abilities as an Integrator

Instructions: This worksheet highlights the key cultural aspects and differences in the workplace. Make copies of the worksheet, and use it when you find yourself playing the role of integrator. Note that Party A and Party B might represent individuals, departments, or teams. You’ve won more than half the battle by simply being able to identify the cultural differences that might exist. You can then use this information to explain Party A’s behavior to Party B (and vice versa), to clear up misunderstandings that are causing, or exacerbating, a dispute. Naturally, good integrators are also good communicators, so be sure to use your tools in this area (see Tool 1–2, as well as Tool 4–5).

Whenever a complaint is made, it’s best to work with the complainant to explore a number of solutions, for the following reasons:

1. If the adversaries are from different social or cultural backgrounds, they may not agree with a principle for resolving their dispute. Thus, a manager may be on the wrong track by appealing to a particular principle.

2. If the adversaries are unaware of a variety of options for resolving the conflict, they may be forced into one that creates even bigger problems for the workplace. For example, if they feel their only option is to use a formal settlement procedure (such as filing a complaint with the human resources office or filing a complaint with their union), they risk (a) not moving forward toward resolving their dispute because they do not want to force a polarized, open conflict situation that such procedures would create, or (b) creating a bigger problem for themselves and the organization, as such procedures tend to polarize the adversaries. A classic example of this problem was brought to light in the Anita Hill–Clarence Thomas controversy that unfolded in 1991 when Thomas went through Senate confirmation hearings for his nomination to the U.S. Supreme Court. Had his former assistant, Anita Hill, seen options in early 1981—when she alleged that Thomas sexually harassed her at the Department of Education—other than going to a formal complaint board, the embarrassing Senate hearings might have been avoided (Smolowe 1991).

3. Having choices offers a measure of power and self-esteem and is often perceived as more fair.

4. Workers who know that their manager will likely help them develop a list of alternatives for resolving a dispute are more likely to come forward and begin redressing problems that are sapping their positive feelings toward the workplace and their productivity.

5. Involving a complainant in developing a list of alternatives encourages complainants to take more responsibility for their lives and become more competent problem solvers, both on and off the job.

6. Providing options is often less costly because people who see options are less likely to take revenge. Rowe has found that the strongest impetus for labor lawsuits against employers is that the plaintiff felt humiliated and could find no other satisfactory way to redress the humiliation. By the same token, sabotage and violence can be provoked by humiliation.

7. Complainants who choose to resolve a dispute by a solution they had a hand in developing are more likely to stick with the solution and take responsibility for its outcome. (And in a case where the outcome is bad, an employer has some protection against a lawsuit.)

The other tenets of principled negotiation provide some of the key methods of generating a list of options (refer to Exhibit 1–2). Managers should have an open-door policy and be willing to communicate. They should develop as much knowledge as possible about the conflict, making sure that each party is factually correct in its assessment of the situation. They should get the disputing parties to focus on interests instead of positions. They should emphasize separating people from issues whenever possible. They should provide alternatives for disputants if the solution cannot be reached in the manager’s office (for example, formal mediation).

The option selected by the manager and complainant may be one of those presented in this chapter. However, the process of arriving at this option—that is, developing a list of alternatives via collaboration between the manager and complainant—brings it under the umbrella of principled negotiation.

A picture is worth a thousand words, so we end this chapter with Exhibit 3–3, which summarizes the seven key approaches for resolving structural conflict.

Organizational structure comprises the various jobs and departments existing in an organization and the relationships among them. This chapter examined a number of approaches that can reduce or eliminate structural conflict—conflict that arises as a result of clashes between different jobs, departments, or teams within the organization. Seven structural conflict resolution techniques were examined: using authority, expanding resources, reducing interaction, clarifying job responsibilities, reducing interdependence, creating integrators, and using principled negotiation.

Managers can use the authority of their positions when dealing with structural conflict involving their subordinates. Requiring little time, authority is a popular conflict resolution approach, but it may only suppress conflict that could soon reappear around a different issue. It also may generate resentment and humiliation.

Because many structural conflicts originate from resource scarcity, managers might consider expanding organizational resources. This built-in slack could prevent serious disputes between jobs, departments, or teams, especially if they must share common resources, such as clerical support, tools, and machinery, but it can also be quite expensive.

Jobs, departments, and teams that frequently interact tend to experience more structurally rooted conflict. By reducing or eliminating interaction, particularly when it involves common resources, managers can minimize structural conflict. But this technique usually involves additional costs.

A more bureaucratic response to structural conflict is the clarification of job responsibilities. As a manager eliminates ambiguous jurisdictional areas between jobs, departments, or teams, the conflict arising from this uncertainty also will be eliminated. This clarification could be expensive, however, because the organization might entangle itself in unnecessary procedures and red tape.

As the dependence between jobs, departments, or teams increases, the opportunity for structural conflict also increases. There are four basic types of interdependence: pooled, sequential, reciprocal, and team. At the lowest level of interdependence (pooled), the probability of structural conflict is low; at the highest level (team), the probability of structural conflict is high. By moving from higher to lower levels of interdependence, organizations reduce the chances of significant structural conflict. Again, this method will involve additional expenses, so it must be determined that the benefits outweigh the costs.

Managers might consider the creation of a special integrator position to help highly interdependent departments or teams deal with conflict. An integrator works mainly in one department (or for one team) but reports to a manager in another department (or to the leader of another team). The major job of an integrator is to bridge the gap and reduce the structural conflict between the two departments or teams. However, this strategy can be difficult, as the individual must be knowledgeable and effective in several areas, and must gain the trust of multiple departments.

Finally, managers should use principled negotiation, especially the tenet of creating options for mutual gain. When complaining employees collaborate with the manager on creating these options, they feel a sense of ownership of the option and the odds increase that once chosen, the solution will work as intended.

1. _________________________ comprises the various jobs and departments existing in an organization and the relationships among them. |

1. (b) |

(a) Structural conflict |

|

(b) Organizational structure |

|

(c) Organizational conflict |

|

(d) Integrated conflict |

|

2. One way to resolve structural conflict involving shared resources is to: |

2. (d) |

(a) eliminate the resources, even when they are useful. |

|

(b) decrease the resources. |

|

(c) keep the resources at the same level. |

|

(d) expand the resources. |

|

3. By clarifying job responsibilities, some structural conflict could be minimized, though at the expense of additional: |

3. (d) |

(a) resources being required. |

|

(b) rules and regulations. |

|

(c) bureaucratic red tape. |

|

(d) b and c. |

|

4. Someone in an integrating position must: |

4. (c) |

(a) be sensitive to race-related issues. |

|

(b) be relatively new to at least one department. |

|

(c) understand the orientations of both groups in which he or she works. |

|

(d) have a legal background. |

|

5. Disputants from different social or cultural backgrounds may not be able to agree on _______________________________ for resolving their dispute. |

5. (a) |

(a) a principle |

|

(b) a common language |

|

(c) what constitutes a reasonable level of conflict |

|

(d) an arbitrator |

|