In This Chapter

Decoding legal codes

Managing the discovery of e-evidence

Operating in good faith

Paying for the e-evidence

Investigators routinely deal with fingerprints, skid marks, bloodstains, bullets, burned buildings, and other traces left by criminals that connect them to the crime scene. What these types of physical evidence may have in common with electronic evidence is that they have no eyewitnesses. When no one has seen or heard a crime in progress to give direct evidence about what they saw or heard, the evidence speaks for itself — so to speak — with the help of experts. It can carry more weight and credibility in a case than direct, eyewitness testimony.

E-evidence is also powerful because it has perfect memory and no reason to lie, and it can't be eliminated or intimidated by a Smith & Wesson weapon. The Achilles heel of e-evidence is that the lawyers, judges, and juries who are involved in the case may not understand the technological details and, as a result, not appreciate the relevance of the e-evidence — at least not until you fluently translate between technology and legal terms so that they can understand.

In this chapter, you find out how rules of evidence, legal procedures, and e-discovery processes converge to create admissible e-evidence — or why it fails to do so.

Laws of evidence play a big role in the career of every type of investigator. The concept of relevancy is the foundation of evidence law. Relevancy is always the first issue regarding evidence because it's the primary basis for admitting evidence.

Note

Here are the first two rules of evidence:

Only relevant evidence is admissible.

All relevant evidence is admissible unless some other rule says that it isn't admissible.

When you think about the logic of the second rule, you quickly realize that the word unless puts a mysterious spin on what admissible evidence is. If you think that the rule is saying, in effect, "Evidence is admissible unless it isn't admissible" — you're right! With these few basic concepts in mind, you can make sense of evidence rules.

With amazing power, the first rule of evidence law splits all facts in a legal action into binary parts: relevant and irrelevant. That sounds simple. It's not, though, because many "buts" are factors on the path from relevant to admissible. "Buts" fall into two categories:

Exclusions: Rules that act like anti-rules. Evidence tagged as an exclusion reverses the rule. For example, one rule says that an e-mail message may be used as evidence. Any exclusion to that rule reverses it. Then that e-mail message isn't allowed as evidence.

Exceptions: Rules that act like anti-exclusions. If an exception to the exclusion is found, the exclusion is ignored. In our example, the e-mail message would become admissible again.

Figure 2-1 illustrates the basic steps in determining whether e-evidence is admissible. Judges have the authority to decide whether evidence is admissible in a trial.

Exclusions and exceptions are discussed in the later section "Playing by the rules." Legal-speak is confusing because it's so often spoken in the negative, or double negative, or worse. Expect to hear a lot of discussion in the negative or double negative; for example, the e-evidence is not inadmissible.

Exploring evidence rules in detail can cause what seems like a temporary loss of consciousness. Mercifully, some rules are obvious or apply only in obscure situations. We condense the rest into an overview of essential rules that you need to know to investigate and prepare cases.

Tip

Clutter is the nemesis of clarity — and your career. Being able to condense material and delete clutter serves you well with judges and juries.

You first deal with evidence and the rules of evidence early in a case, during discovery, the investigative phase of the litigation process. When you deal with e-evidence, this process is cleverly referred to as electronic discovery, or e-discovery. Each side has to give (or produce) to the other side what they need in order to prepare a case.

Discovery rules are designed to eliminate surprises. Unlike in TV dramas, surprising your opponent with information, witnesses, or experts doesn't happen. If you think about it, without rules against surprises, trials might never end! Each side would keep adding surprises.

You can think of discovery as a multistage process, most often a painful one, of identifying, collecting, searching, filtering, reviewing, and producing information for the opposing side in preparation for trial or legal action. For e-discovery, you as a computer forensic expert play a starring role, as do the software and toolset you use. Many cases settle on the basis of information that surfaces during discovery and negotiations.

E-discovery demands can become a weapon in many cases. Parties have even been forced to settle winnable cases to avoid staggering e-discovery costs. E-discovery rules try to prevent the risk of extortion by e-discovery. Suppose that a company estimates that defending itself in a lawsuit would cost $1.3 million for e-discovery plus other legal fees. If the company were being sued for less than e-discovery costs, the case wouldn't get to court. The company would be predisposed to settle the lawsuit to avoid the cost of the e-discovery process.

Legally, evidence is material used to persuade a judge or jury of the truth or falsity of a disputed fact. Rules of evidence that control which material the judge and jury can consider (what's in) and which they cannot consider (what's out) vary depending on the type of case and court. (We cover only federal court.) Three primary rules determine this in-out split:

Federal Rules of Evidence, or Fed. R. Evid.: Used by federal courts to determine which evidence is relevant in civil or criminal cases. To be admissible, information must be relevant and material (useful) to a disputed issue.

Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, or Fed. R. Civ. P.: Control discovery and e-discovery during civil litigation in federal court. In 2006, amendments to the Fed. R. Civ. P. specifically addressed electronically stored information, or ESI, to make e-discovery less of a guessing game. The rules were completely rewritten to make them simpler, clearer, and more specific about ESI. Now, all ESI that's relevant to a legal action, no matter how glaringly incriminating, must be made available for discovery. The jury is still out (an irresistible pun) on how helpful the new rules are. They may have made life easier for investigators by "motivating" organizations to preserve ESI and by handing out harsh penalties when it isn't preserved. You find out about these rules in greater detail in the "Managing E-Discovery" section, later in this chapter.

Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure: Control the conduct of all criminal proceedings brought in federal courts to ensure that a defendant's rights are protected.

Note

In ruling on the appropriateness of producing ESI in a criminal matter, Judge John M. Facciola said that it would be "foolish" to disregard Fed. R. Civ. P. because the problems associated with the production of electronic documents are the same whether the matter is civil or criminal (United States v. O'Keefe, Feb. 2008).

Computer forensics often deals with circumstantial (indirect) evidence. Circumstantial evidence in every case is divided into two categories: relevant and irrelevant. Anything that a Federal Rule or judge says is irrelevant is excluded. Relevant material remains in play, but is whittled away until all that remains is the evidence that the judge or jury uses to decide the outcome.

Note

The judge decides which evidence is admissible. The jury decides the weight and credibility of the admissible evidence.

Common exclusionary rules and some of their exceptions are

Hearsay evidence: This unreliable, secondhand evidence isn't allowed. But the hearsay rule has 30 exceptions. For instance, electronic and paper business records are hearsay, but business records created in the ordinary course of doing business are an exception. Therefore, e-mail and other electronic records are admissible as business records as long as their reliability can be proved.

Privilege: Certain communications, such as between an attorney and client, are confidential and protected by law. Documents created as part of the legal preparation for a client are work product and are also privileged. Work products include documents and reports from or to a client, witness, or computer forensic investigator. Privilege applies to electronic communications and work product. You always need to be careful with your communications during a case.

Waste of time: Evidence must have probative value — it must relate to an element of the case and be capable of proving something worthwhile. If it can't, the court doesn't waste its time. Evidence that needlessly delays a trial because it has no reasonable connection to the disputed issues is excluded.

Confusion of the issues or misleading the jury: Even if the e-evidence isn't knocked out of court because of an exclusion, you must still overcome another hurdle — most jurors don't understand computers beyond the basic familiarity needed to operate them (such as sending e-mail and searching the Internet). And, the education level of the typical juror is roughly eighth grade. Not confusing or misleading this group may be your greatest challenge and triumph.

Most of the battles and decisions about what's relevant evidence and what's not takes place during e-discovery. You can see how critical this stage is. Lawyers who lose the e-discovery battle can safely expect to lose the case, unless they're saved by a technicality or other loophole. Anyone who violates the rules of discovery, either deliberately or from negligence, can also expect to feel the fury of the court. Failure to comply with electronic production obligations can lead to serious sanctions, sometimes to the tune of millions of dollars. For example, in Best Buy v. Developers Diversified Realty (2007), the responding parties argued that e-mails that they were ordered to produce were stored on backup media, and therefore, weren't reasonably accessible. The judge wasn't swayed by the problem and ordered that the ESI be produced within 28 days.

Lawyers can use any of these rules to influence which evidence is excluded by raising an objection based on one of them. If the judge sustains a lawyer's objection, that evidence is excluded. If the objection is overruled, the evidence remains.

Note

In the 2007 patent infringement case over video compression patents that Qualcomm brought against Broadcom Corp., it was learned during trial that Qualcomm failed to produce relevant e-mail. It produced 1.2 million pages of marginally relevant documents while hiding 46,000 critically important ones. Qualcomm argued that its attorneys failed to produce the evidence. The 19 attorneys argued that they had been hoodwinked by their client. The judge didn't believe either side and sanctioned them both.

E-discovery is a brawl between two opposing sides: the requesting party and the responding (or producing) party. This brawl is hostile, ugly, and subject to the Federal Rules (see the previous section).

Here's how e-discovery works:

The requesting party submits questions to the opposing party to learn the lay of the opposing party's digital landscape.

The responding party (the respondent) provides answers. The answers also identify information that the responding party needs to preserve.

The requesting party formulates the request for the production of ESI.

The responding party can agree with or dispute the request. Disputes that parties can't settle are decided by the court.

In the following sections, we take a look at difficulties you have to overcome with e-discovery.

In the area of e-discovery, timing is critical and you must follow the deadlines. Fed. R. Civ. P. Rule 26(f) imposes deadlines regarding e-discovery:

Rule 16, Pretrial conferences: Requires opposing parties to meet and discuss a discovery plan and evaluate the protection and production of ESI within 99 days of the filing of a lawsuit.

Rule 26(a), initial disclosure of sources of discoverable information: Parties must identify all sources and types of ESI to the opposing side according to a time schedule imposed by the court.

During the trial of Z4 Technologies v. Microsoft (2006), it came to light that certain e-mail evidence hadn't been produced during discovery and that the existence of a database wasn't disclosed. The judge ordered Microsoft to pay additional damages of $25 million plus $2 million in lawyer's fees for litigation misconduct.

When a lawsuit is filed, rules trigger and a clock starts ticking toward several deadlines. The total elapsed time from a lawsuit filing to an e-discovery plan being presented to the court is 120 days:

Day 1: The lawsuit is filed and served on the defendant.

By Day 99: Opposing parties must meet and confer for a planning session. From this negotiation comes an e-discovery plan. Discussion topics and questions to be settled include the ones in this list:

What ESI is available?

Where does the ESI reside?

What steps will be taken to preserve ESI?

In what forms will ESI be produced?

What's the difficulty and cost of producing the ESI?

What is the schedule of production?

What are the agreements about privilege or work-product protection?

What ESI will not be produced because it is not reasonably accessible or is an undue burden?

By Day 120: The e-discovery plan is due to the court by the representing attorney's office, which is usually a paralegal.

If you're not armed with all details and the expert help necessary to negotiate the scope of discovery at the planning meeting, you can't possibly set up a favorable plan. The next section goes into detail about why it's so important to have a favorable plan.

To understand how to negotiate an e-discovery plan, you have to take time to appreciate the causes of the conflict. ESI differs from paper-based information in ways that add to the complexity of e-discovery and disputes about it. This list describes several of those differences:

An exponentially greater volume of ESI exists.

Consider all the electronic gadgets that people carry, the number of people addicted to social networking and blogging (rather than working) while at work, and the volume of texting and e-mail. Then factor in backups and the fact that nothing is deleted. Now you have a picture of why the volume of ESI far exceeds that of paper.

ESI is located in multiple places and on multiple devices.

Portable data devices are standard equipment for many people. Imagine trying to round up handheld device and portable storage devices that might contain discoverable e-content, as well as servers and massive data warehouses.

ESI has final versions and intermediary draft versions.

Backup systems catch draft versions and rarely does anyone even think about it — until e-discovery.

ESI has invisible but relevant metadata and embedded data.

Most often, ESI must be produced in its native format and not be printed and submitted. The requesting party wants access to the metadata that could support its side of the case.

ESI is dependent on the system or device that created it.

After a company's data is backed up to tape, it usually doesn't create new backups when upgrading its system. When those tapes must be restored, the company probably doesn't have the equipment to do it. The same concept applies to new accounting or financial systems. A company may need to produce 4-year-old financial records in a fraud investigation. If it has switched accounting systems, though, it can't retrieve the records.

Finding relevant and responsive data in every possible location, filtering it to remove content that is not requested or that is privileged, de-duping the data to delete duplicates, and further processing the data to produce the smallest volume can easily cost a million dollars. It costs roughly $1,000 to restore and search one tape. If a company has 20,000 backup tapes containing millions of messages, the tally for that electronic search is $20 million.

The volume and intractable sources of ESI can cause disputes about the scope of discovery. Lawyers are looking for "dirty laundry" or "smoking guns" or fighting other lawyers' attempts to uncover them. The requesting lawyer takes anything that you hand over. Your job is to limit the amount the opposing side receives.

If the requesting party demands all e-mail messages and documents contained on the defendant's laptop and Blackberry or similar device, and the passwords needed to inspect them, there's going to be a fight.

Such a broad request (all documents and e-mail messages) will fail. The reason is that courts try to limit production to material and necessary e-evidence only to protect responding parties from the unfair burden of excessive costs and overbroad requests. In reviewing specific requests for ESI, the court rejects requests that, in its opinion:

In plain English, wildly speculative requests are rejected. To succeed, your requests need to be specific (give dates and names) and tailored (state specific subject matter or keywords) and give a reason for each ESI demand. (No buckshot approaches are allowed here.) Limit requests to ESI that's both material and necessary to the prosecution of the case or action.

Warning

An overbroad request puts the whole request in jeopardy. The judge can reject (or vacate, in legal-speak) the request entirely, and you would forfeit your chance to get hold of ESI that was relevant.

There are no easy ESI requests: Requesting ESI is tedious, specialized work. You can't just say "Turn over your e-mail and spreadsheets." That's too broad. Shaping a request requires knowing the opponent's computer systems, including operating systems, networks, databases, e-mail system, backup procedures, and application software. It requires understanding what ESI is relevant and where it is, such as metadata and hidden files.

Because you're an expert at recovering data, you can play a vital role by helping frame and shape requests and formulate the e-discovery strategy. From our experiences, computer forensic experts acting as consultants help the legal team by identifying data sources they had not thought to request.

You can help demonstrate the reasonableness of a producing party's efforts in the following ways:

Identify the custodians of the ESI, who has it, and who knows how and where it was created and stored.

Specify types and locations of the ESI, date ranges, and keywords to use in the searches to limit the scope of responsive documents, data, and e-mail.

Warning

Except for unusually small cases, responding to e-discovery requests cannot be done without the use of an e-discovery or computer forensic toolset (toolkit). Forensic toolkits are discussed in Chapter 6. Several toolsets and experts may be necessary because of volume and a variety of data sources.

When you receive a request for e-discovery, you have to respond to it. Here's how:

Identify the types, sources, and locations of the ESI being asked for.

This is a good time to identify which information might be privileged and, therefore, protected against disclosure.

Preserve the ESI.

You must protect the ESI from destruction and alteration. Forensic data capture is quite important at this stage. If files or e-mail have been deleted, creating forensic copies of the ESI is essential. Inform all owners and holders of the identified ESI not to delete it and explain why. The forensic copies of backups can save the day when people react to a preservation order by deleting them instead. A preservation order is a legal notice that ESI must be preserved for a lawsuit that will be filed or has been filed. In 2004, Philip Morris was sanctioned $2.75 million for failing to preserve electronic information.

Start collecting from all applicable sources and devices.

Potential e-evidence must be accounted for from collection until admittance at trial to prove its authenticity. Documenting the chain of custody of potential, relevant evidence to disprove tampering or alteration is critical to admissibility at trial. Chain of custody is the process by which computer forensic specialists or other investigators preserve the ESI or crime scene. It documents that the e-evidence was handled and preserved properly and was never at risk of being compromised. The documentation must include

Where the evidence was stored

Who had access to the evidence

What was done to the evidence

You must carefully document each step so that if the case reaches court, lawyers can show that the ESI wasn't altered as the investigation progressed. Without a documented chain of custody, it's impossible to prove after the fact that evidence has not been altered. Computer forensic toolkits perform that necessary recordkeeping and documentation of proper handling. A big complication is restoring backup tapes so that ESI can be collected from them.

Process and filter the ESI.

The collection process resembles a huge fishing net that catches too much. The ESI-catch needs to be filtered to remove files that are outside the scope, duplicates (also called de-duping), confidential, or privileged. Record what happens, and why, in a report that will accompany the produced ESI. Again, you can complete this step with forensic software. With computer forensic tools, a complete search for deleted documents and e-mails can be done in a much shorter period in order to identify items of privilege.

Review the ESI.

Whatever remains at this stage needs to be reviewed. That is, someone has to read it and decide what to do with it. Inarguably, now is the time to flag any hot files that are incriminating or embarrassing. (You want to get out in front of that possible train wreck.)

Analyze the ESI a final time.

This final review is usually done by people who would be preparing this case for trial, which include the lawyers, paralegals, assistants, and law school students.

Deliver the ESI and reports to the lawyer you work for.

Remember to include reports that authenticate the e-evidence and verify that the chain of custody was preserved. A copy of your reports must reach the lawyer in time to be delivered to the opposing lawyer before the deadline.

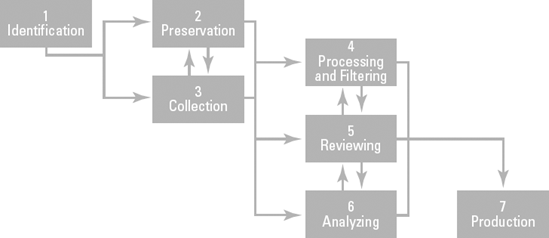

Figure 2-2 shows the steps in this process.

The Fed. R. Civ. P. require parties to respond to e-discovery in good faith. To act in good faith means to be fair and honest. A party acts in good faith by not taking an unfair advantage over another party. Acting in good faith isn't optional in legal cases — it's a legal obligation. When either party finds e-evidence that will bury its case, that faith becomes severely strained. This statement may be tough to believe, but it's better to try to explain a smoking gun at trial than to explain why it's missing. The latter puts you at the mercilessness of the court.

When you don't conduct good faith, you may damage, or spoil, the case. Spoliation includes not only deliberate destruction of evidence but also any change or alteration from neglect, accident, or mistake. Put another way, spoliation is a powerful tool for the opposing side. Your opponent can use it to persuade the judge or jury that it would have proven their case.

Warning

Acting in good faith is a duty and is never optional.

E-discovery is an obligation on all litigating parties: the litigants, their computer staff, legal team, and investigative team. The legal team is obligated to perform a reasonable investigation (or good faith effort) to determine whether its client and investigative team have complied with its e-discovery obligations in good faith. Managing the e-discovery process and parties involved in it is similar to herding cats: They're not easily controlled or motivated.

What if, for example, the company (the responding party) involved in analyzing and producing ESI deliberately or unintentionally fails to turn over incriminating files? Does the legal team have a duty to send in the equivalent of Imperial storm troopers to verify the loyalty and obedience of their clients to the e-discovery rules? The answer is not No (another example of double negatives).

Courts cut no slack to anyone who violates e-discovery. Only lawyers or clients with a death wish or serious ego problem hide evidence from the court.

Sloppiness in checking for ESI has the same result as hiding it. When ESI isn't produced, trial courts don't care who is at fault or why. The consequences for people who trifle with the court usually aren't pretty, and reach well into the millions of dollars.

Tip

The safe harbor rule says that, except for exceptional circumstances, a court may not impose sanctions on a party for failing to provide ESI that's lost as a result of the routine, good-faith operation of an electronic information system.

The debate surrounding e-discovery involves not only what types of electronic data can be discovered during litigation but also who should have to pay for producing the ESI. Traditionally, the producing party had to pay the costs of reviewing, copying, and producing documents. The need to hire computer forensic experts and consultants to perform the search to respond to e-discovery requests greatly increases the costs.

In the 2003 landmark case of Zubulake v. USB Warburg, U.S. District Judge Shira A. Scheindlin warned that "discovery is not just about uncovering the truth, but also about how much of the truth the parties can afford to disinter."

To decide which party should pay for e-discovery costs, Judge Scheindlin looked at five criteria of the data:

Active, online data: Data that is in an "active" stage in its life and is available for access as it is created and processed. Storage examples include hard drives or active network servers.

Near-line data: Data that's typically housed on removable media, with multiple read/write devices used to store and retrieve records. Storage examples include optical discs and magnetic tape.

Offline storage and archives: Data on removable media that have been placed in storage. Offline storage of electronic records is traditionally used for disaster recovery or for records considered "archival" in that their likelihood of retrieval is minimal.

Backup tapes: Data that isn't organized for retrieval of individual documents or files because the organization of the data mirrors the computer's structure, not the human records-management structure. Data stored on backup tapes is also typically compressed, allowing storage of greater volumes of data, but also making restoration more time consuming and expensive.

Erased, fragmented, or damaged data: Data that has been tagged for deletion by a computer user, but may still exist somewhere on the free space of the computer until it's overwritten by new data. Significant efforts are required to access this data.

The first three types of data are considered accessible, and the last two types are considered inaccessible. For data in accessible format, the usual rules of discovery apply: The responding party pays for production. When inaccessible data is at issue, the judge can consider shifting costs to the requesting party. If the requesting party wants it, it has to pay for it. This burden limits overbroad and irrelevant requests.

The Zubulake test examines seven burden factors, listed in decreasing order of importance; the first two are the most important:

The extent to which the request is specifically tailored to discover relevant information

The availability of such information from other sources

The total cost of production, compared to the amount in dispute

The total cost of production, compared to the resources available to each party

The relative ability of each party to control costs and its incentive to do so

The importance of the issues at stake in the litigation

The relative benefits to the parties of obtaining the information

The last two factors rarely come into play. Consideration of these seven factors helps the court decide whether the e-discovery process is burdensome and, if so, whether the responding or requesting party, or both, should pay for its production. Zubulake ultimately concluded that the requesting party should pay 25 percent of the cost of e-discovery.