In This Chapter

Choosing cases wisely

Proving that you can prove the case

Pleasing the court with credentials

Getting up to speed

Closing and controlling loopholes

Legal hardball is expensive, irrational, and rampant. Parties involved in commercial or civil litigation often defy rational behavior. (Commercial litigation covers business and employment disputes.) In contentious divorce actions, the crazy-meter can go off the chart. Litigation cases range from relatively simple matters to complex, money-burning sagas that take years to resolve.

For all types of cases at all times, the devil is in the details. Small items in an investigation, if overlooked, open loopholes that the opposing side can use to undercut your results and make you look incompetent. Loopholes may be either party's best or only chance of winning. Learn how to harness loophole power. The opportunity to harm the case or be humiliated on the witness stand is unlimited, for either not following standard procedure or not being able to defend what you did or did not do. By making informed choices about forensic methods and work habits, you defend your analysis and opinions from fact-spinning by the opposition.

In this chapter, we begin by discussing your entree into civil or criminal cases. The focus is mostly on cases where you aren't working with a prosecutor (see Chapter 3) or securing a crime scene (see Chapter 4). You decide whether to take a case, and if you do, what arrangements are involved. Then you view cases from the perspective of your client, the lawyer who's considering hiring you. After these preliminary tasks are finished and you're on the case, you find out about legal loopholes whose existence and size are determined by your defensible forensic methods. Here's to a favorable outcome to your cases.

You may come up against tricky situations. For example, a lawyer facing an upcoming court date may want a preliminary expert opinion from you about the strength of the prosecutor's e-evidence, which would be delivered on CD to you by the next morning. Don't make hasty commitments. Unless you're experienced enough to know that you can perform the review properly by the deadline, you put yourself and the case at risk if you agree.

You shouldn't accept, without consideration, every case that's offered to you. The field of forensics is labor intensive and deadline driven, which limits the number of cases you can take on at a time. In addition, not all cases are appropriate for every investigator, nor is every investigator appropriate for each type of case. You'll face cases and clients that you're willing and able to take on and also face some that you're not. How do you decide? You start by learning about your prospective client's case, priorities, and resources.

Tip

Taking on only one type of case and client, such as only criminal cases involving assault or harassment for the defense, can be risky because you could appear to be an expert for hire or a professional witness.

You need to know what type of case you're being asked to take to determine whether it's within your area of expertise. For example, in a contract dispute, the lawyer knows which documents need to be retrieved. But a fraud case requires familiarity with a chart of accounts or ACL (auditing) software, so you should refer the attorney to a forensic accountant or suggest that one also be retained.

Note

If you cannot accept a case, admit it politely and immediately to save everyone's time and to protect confidentiality. Before the call ends, you might identify your areas of expertise for future cases or follow up with a mailing.

Find out which evidence has been confiscated or taken into custody and when. Most likely, the lawyer will explain what happened and who was involved. Ask about any DIY activity.

Take good notes and label them, but do it quickly. Neatness doesn't count here, and you don't need to write out every word. Sketch a timeline or chart relationships among people, if appropriate. For the most part, you're listening and limiting your questions only to clarify points. For example, if computers were confiscated, you might ask whether only the defendant had access to devices that were confiscated or if any others had access too. Considering how long it takes for a case to reach trial, don't be surprised to hear that events happened more than a year earlier.

If the case involves suspected possession of child pornography (CP), law enforcement will already have confiscated all computers and equipment. Ask for, or at least mention, that you would need the name and contact information of the prosecutor's computer forensic investigator.

Each case has a theory — a theme that unifies the evidence to tell a believable or compelling story. Ask about the theory and try to identify which, how, and whether e-evidence can support it. A common defense theory used in wrongful termination cases, for example, is that the employee was fired because of poor performance. Ask to review the plaintiff's (former employee's) performance reports and those of comparable employees, the metadata of the files (see Chapter 11), access logs, and hard copies of those digital reports. If performance reports were edited to manufacture e-evidence showing that the firing was for poor performance, the metadata indicates the date of the edit. No matter how hard one tries, mistakes in editing documents get made. You need to find them. By comparing the hard copy to the digital copy, you can detect those human mistakes or oversights that lead to inconsistency between the paper and digital versions. Look for volatile (changing) fields within the document or its headers and footers that are automatically updated, such as the Today field (or =TODAY() function) that inserts the current date. Paper doesn't update itself!

Warning

Avoid cases where the plan is to tamper with the e-evidence to make it fit the theory after the fact. Without fail, mistakes will be made. It's like trying to commit the perfect crime: Something is always overlooked. In a wrongful termination case, a company instructed its human resources (HR) department to change the fired employee's evaluations from Commendable to Poor. Evaluation forms were formatted Excel spreadsheets with Date and Time fields in the headers and footers. When a user works in Excel, the header and footer aren't visible on the screen, so the HR person making the edits overlooked the updated dates that appeared on the pages as they were reprinted. The company submitted the tampered performance reports — showing that they were all printed on the same day just weeks earlier.

Every case brought before a jury should have a memorable (short) theme based on the theory of the case. A theme can be crafted around an answer to a question, such as "If no [pick one: harassment, discrimination, negligence, policy violation] occurred, why are we here?"

Investigations run up against the usual limits of available time and money. Many legal deadlines exist for case filings, responses to case filings, and court appearances. Lawyers may not plan for your services far enough in advance of their court-imposed deadlines, such as filing with the court or appearing before a judge. If you can do the work by the deadline, consider accepting the case subject to the issues discussed next. You need time to think through the elements of the case. You also increase the risk of making mistakes or overlooking vital issues if you're in too much of a rush.

You cannot perform investigative miracles, but you might be expected to. Tradeoffs apply to the quality, time, and cost of your work. Here's a simple law of investigative work:

Quality work takes more time and costs more money.

When presented with a case, find a smooth way to lay out three factors and ask the client to "pick two." The client may want all three, but that's not feasible. Have the client pick the type of work to be done:

Fast (time)

Cheap (total cost)

Right (quality of work)

Be sure to get a response so that you know which factors are important to the people paying for your expertise. Clarifying these issues up front might make getting paid easier, when the client gets your bill (see Chapter 17). The client can't deny being informed that a quality investigation takes more time, as reflected in the final tally. You can't guarantee that the forensic method (see the "Keeping a Tight Forensic Defense" section, at the end of this chapter) of acquisition through reporting of e-evidence can be done right, quickly, and cheaply.

Warning

Litigants may be driven by strong emotions, possibly called principles, that defy rational behavior. Individuals whose emotions are inflamed tend to make bad decisions, even rejecting amazingly generous settlement offers given the strength of the e-evidence. (The party on the receiving end of this emotional battle may want to settle the case as soon as possible and may not care or may not be aware of how much e-evidence has been found.) Plaintiffs may refuse to follow their lawyers' advice and want you to keep digging. You're neither legal counsel nor therapist. Confine yourself to your area of expertise — the e-evidence.

Limits apply to how fast an investigation can be done because of the devices to be forensically examined. Travel time and your availability are obvious to the client. Key factors influencing the elapsed time to forensically investigate a computer that clients may not know about are described in this list:

Speed of the hard drive being imaged: A major choke point of imaging a computer is the speed of the hard drive being imaged. You can't begin to search until after the hard drive has been forensically imaged.

Clarity of the search and volume: In some cases, a person knows what they need, and search terms lead to the documents, e-mails, and other evidence. In other cases, a person suspects or wants to find out what's going on — fishing expeditions looking for e-evidence. Consider the difference in these two scenarios:

A business owner needs to recover the original copy of a contract that he only recently learned had been altered. He had composed and e-mailed it to a longtime contract worker. The worker altered the terms of the contract and e-mailed it back when the owner was out of town. The owner didn't inspect the document and never saw the changes. Over a year later, the contract is being enforced. The owner wants a computer forensic investigator to recover the original contract from the computer and e-mail.

An individual in the process of a divorce suspects that his spouse, who uses several computers, is hiding assets or indiscretions. You don't have much material to work with — just the individual's suspicions.

Contamination by do-it-yourselfers (DIYs): If a do-it-yourselfer starts to investigate hard drives or e-mail and contaminates the evidence, you might have to figure out some way to work around the contaminated data, such as finding e-evidence on the recipient's computer or backups somewhere off-site.

From watching news of the crimes and misdemeanors of high-profile individuals or companies, you know that new e-evidence oozes out as cases unfold. An event that starts off as a minor violation can erupt into multiple felony charges. By now the entire world should know that text and e-mail messages might, in effect, be carbon-copied (CC'ed) to major news organizations, such as CNN, Fox News, and The New York Times.

Before agreeing to a case, define your scope of work. You use two standard documents for this purpose:

Case intake form: The case intake form is similar to a questionnaire. You collect information to set up an investigation. Questions differ according to the type of case: civil, criminal, matrimonial, insurance, or private.

Letter of agreement: This letter describes your fee, payment details, and perhaps a retainer.

To see an example of an intake form for use by law enforcement, see pages 58–61 of the Forensic Examination of Digital Evidence: A Guide to Law Enforcement, by the Department of Justice (DOJ), at www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/nij/199408.pdf.

Note

Be alert to changes in scope because a client may not be willing to pay more in legal fees, including your fee, than the amount stipulated on the contract. This advice sounds simple enough, and it is — as long as the scope of the work for the lawsuit doesn't change. If the value of the case spikes, the scope of the case changes, in addition to your fee. Certain types of lawsuits spiral outward, such as negligence cases. If the contract doesn't address what happens when the scope of the cases changes, you may cheat yourself out of a fee.

Lawyers want to know whether you can help prove their case, build a case, or defend their clients. Crimes aren't crimes and rights aren't rights without proof. A careful lawyer always has an eye on which information can be proved and who can prove it.

Typically, before discussing a case with you, a lawyer reviews your résumé to make sure that you have the proper credentials or qualifications. Keep your résumé updated and honest because you may be asked about it under oath in court or in a deposition. Lawyers also need to verify that no conflict of interest exists. You cannot have ties to any party involved in the case. Bias creates a loophole.

Sound like a pro. The lawyer is now uncertain about you and the e-evidence. Most likely, if the lawyer is familiar with the concept of forensic software, she has already mentioned it in this call. To be a helpful coach, explain the computer forensic process as you would explain it to a jury — in simple-to-understand language using analogies (see Chapter 17). By doing so, you're also demonstrating your ability to explain technical topics to a jury.

Be sure to explain these basic concepts of how computer forensic cases work:

Forensic imaging is done by the prosecution, not by the defense in criminal cases.

The DA's office or law enforcement confiscates computers and devices. Forensic imaging is done by the DA's computer forensic experts or by experts at a regional computer forensic lab (RCFL). The government doesn't give back computers that contain contraband. Explain that only one forensic image is needed. Each side examines the image, if it's allowed by law. A government office or the DA's office provides a copy of the image unless it contains contraband (such as child pornography). In those cases, the defense may receive the report only on a CD or DVD that has been produced by FTK, EnCase, or similar software.

Tip

The defense may receive a paper copy of the report with some redacted sections, a digital copy of the report produced in an Excel spreadsheet on CD in hypertext, and a listing of filenames, dates, and locations.

Make clear that your role in criminal cases focuses on reviewing the reports and materials provided by the DA's computer forensic expert.

All the lawyer has to do to view the e-evidence is insert the CD or DVD into a computer and click on the reports to open them in a Web browser. Evidentiary documents, photos, e-mail messages, files, and Registry entries, for example, are all available in a readable format with the click of a mouse.

As an investigator, don't expect to simply be an order-taker. Clients don't say "Check this out and get back to me." They may not realize what they don't know. You're much more valuable when you take both active and educational roles. The types of help you might be asked to provide are described in this list:

Find e-evidence to prove that something happened.

You might be looking for e-mail indicating sexual harassment, financial files indicating fraud or IRS violations, or file transfers indicating theft of intellectual property.

Find e-evidence to prove that someone did not do something.

You might prove that image files of child exploitation on a person's office computer could have been downloaded by another person because the computer had no password or firewall protection.

Figure out what the facts prove or demonstrate.

This advice includes the discovery of harassing jokes that had been routinely circulated or forwarded by way of the company's e-mail system or of files and e-mail indicating patent violations.

Examine the prosecution's or opposing counsel's e-evidence for alternative interpretations.

You might prove that an allegation that the defendant manipulated accounting software isn't supportable by the e-evidence that has been provided.

Assess the strength of the e-evidence against a suspect.

Sometimes the client and the accused need to know what the prosecution knows in order to decide whether taking the plea deal or probation is the right choice. Pleading guilty carries less jail time than being found guilty.

Scrutinize experts' report for inconsistencies, omissions, exaggerations, and other loopholes.

Cases involving e-evidence usually have two computer forensic investigators — one for each side. The prosecution or plaintiff's side has the burden of proof, so their investigator prepares a report. Regardless of which side you're on, you need to evaluate, and possibly rebut, the opposing expert's report. (See Chapter 16.)

Warning

Not getting caught in a lie isn't the same as telling the truth. Judges and juries don't like being fooled with. When you take on a case, recognize that you might have to raise your right hand and swear to tell the truth about the investigation and what you did.

Depending on whether the lawyer interviewing you represents a plaintiff or a defendant and the type of case, you might hear various versions of the question "Can you help my case?" You might be asked these types of questions:

Is there another explanation for how the files got there?

How can we prove that the e-mail wasn't sent from a computer by way of the company's network?

How do we prove the geographical location of the machine used to send or receive files?

What else could the e-evidence mean?

What other theory can explain why the files were deleted or missing?

Was my client's computer capable of viewing the images or downloading those files?

Which statements or allegations in the affidavits are vague?

How might the opponent's expert mishandle or taint the e-evidence?

If e-discovery and the production of electronic documents are involved, you're asked to provide expertise on those issues too.

Note

We've seen alarming misinterpretations of e-evidence — based on ignorance or false hope or just plain deliberately. Sometimes e-evidence, like physical evidence, by itself or out of context just cannot be interpreted. For example, a manager might accuse an employee of stealing customer files before resigning. Technically, copying a file to external removable media (a CD or flash drive) creates a .lnk (link) file. Suppose that a lot of .lnk files are found on the former employee's laptop using forensic software such as EnCase or FTK. But that analysis was done on the laptop after another employee had been using it for weeks. For the client, that's sufficient proof that the employee stole intellectual property (IP), but it has no evidentiary value. It's possible that a specific employee can be associated with .lnk files and the IP, but only if someone finds the device on which those files were copied. Otherwise, too many degrees of separation — or breaks in the chain of evidence — exist between the former employee and the IP files on the reused laptop. No defensible interpretation about the .lnk files is possible.

If you believe that you can perform an investigation fairly, impartially, and thoroughly and state your findings in a signed document, do the following:

Say "I accept."

A clear reply indicates to that client that you made a decision. Don't assume that you gave enough signals for the client to figure out your intention.

Sign an agreement or a contract that details, as much as possible, tasks to be done, deadlines, costs, and payment schedules.

Be sure that it's clear who is responsible for paying your invoices. All parties must read and sign the contract so that if something goes wrong, no one can plead ignorance.

Note

At some point, you report your findings with an introduction that begins something like this: "Within the bounds of reasonable computer forensic certainty, and subject to change if additional information becomes available, it is my professional opinion that... ."

Most 21st century litigation relies on the testimony of experts — including computer forensic experts. Expert testimony plays a deciding role in a lot of litigation, so it's not a surprise that the U.S. Supreme Court has ruled several times on who qualifies as an expert and the admissibility of expert scientific testimony in a federal trial. These rulings ensure that your testimony is reliable and can be evaluated by a judge and jury.

The reliability standards began in 1923, with the Supreme Court decision in Frye v. United States, which began tests of expertise for experts. The Court held that, to be admissible, expert testimony had to

Rely on principles that were "generally accepted" by the scientific community

Be able to meet the standards of peer review

As a result of Frye, your reputation and achievements in the forensic field comprise the central question of admissibility of your testimony. It's an objective standard for courts to apply when trying to distinguish your legitimate testimony from fantasies of quack and crank scientists. But Frye created a problem when lawyers began gaming the system. Frye didn't or couldn't protect against experts-for-hire.

Tougher federal regulations and Supreme Court precedents replaced Frye — primarily Daubert and Rule 702. In the 1993 Daubert v. Merrell Dow opinion, the Supreme Court set stricter criteria for the admissibility of scientific expert testimony. State courts' set their own standards based on Frye, Daubert, or Rule 702.

The Daubert test is primarily a question of relevance or fitness of the evidence. For testimony to be used, it must be sufficiently tied to the facts of the case to help understand the disputed issues. (See the blog on Daubert issues at http://daubertontheweb.com/blog702.html.) But Daubert didn't apply to nonscientific expertise.

To fill that gap, in the 1999 Kumho Tire v. Carmichael opinion the Court extended Daubert to also include nonscientific expert testimony. For technical or other specialized knowledge, Fed. R. Evid. 702 applies.

Rule 702 broadly governs the admissibility of expert testimony. The rule

States "If scientific, technical, or other specialized knowledge will assist the trier of fact to understand the evidence or to determine a fact in issue, a witness qualified as an expert by knowledge, skill, experience, training, or education, may testify thereto in the form of an opinion or otherwise."

Permits nonscientific expert testimony as long as it helps the trier of fact.

Imposes these requirements on technical or other specialized knowledge witnesses:

The witness must possess such a relevant form of knowledge.

The knowledge must assist the trier of fact.

The witness must be qualified as an expert.

Expect opposing counsel to question your credentials. See Chapter 18 for ways to add to your qualifications.

When an expert's analysis is based on an objective metric or standard (for example, the standard in Italy that fingerprints are a match to a person if they have 17 points of similarity), jurors decide for themselves whether the expert's conclusions are valid. If the expert can show only a 13-point match, the jury can make a comparison. But as Chief Justice William H. Rehnquist pointed out in the 1997 case General Electric Co. v. Joiner, when the standard is subjective, the jury has to accept an expert's conclusion as ipse dixit (the only proof of the fact is that this expert said it). The jurors lack a standard against which to assess and decide whether a conclusion was reached correctly.

The court in the Daubert case pointed out that the availability of data about a technique's error rate is important to decide if an analytic method is admissible. For example, when juries know that a computer forensic toolkit has a 3 percent error rate, they're better able to intelligently determine the believability of the expert's opinion that is based on that toolkit. But without knowing about the toolkit's reliability, a juror may decide solely on the expert's personality, credentials, or other irrelevant factors.

After you accept the case and the lawyer is satisfied with your credentials, it's time to get started with the case. In this section, we discuss how to get up to speed with the case, how to organize your files, and how to search for background information on the case.

The first thing you must do is obtain permission from the lawyer to call the district attorney's (DA's) forensic expert to discuss the case.

To conform to the Adam Walsh Child Protection and Safety Act of 2006 (often abbreviated as AWA), you may need to make arrangements to view the e-evidence. Section 504 of the AWA states that

(1) In any criminal proceeding, any property or material that constitutes child pornography ... shall remain in the care, custody, and control of either the Government or the court.

(2)(A) Notwithstanding Rule 16 of the Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure, a court shall deny ... any request by the defendant to copy, photograph, duplicate, or otherwise reproduce any property or material that constitutes child pornography ... so long as the Government makes the property or material reasonably available to the defendant.

Reasonably available to the defendant means that the government provides ample opportunity for inspection and examination at a government facility by the defendant, his attorney, and anyone who will provide expert testimony at trial.

Defense lawyers have criticized the AWA for limiting their two most frequent defenses:

Whether a digital image depicts an actual child and isn't a virtual image or a digitally altered adult

Whether the defendant knowingly possessed or received the image. That is, that the contraband images had not been transferred or downloaded to the hard drive by malware or some other source unbeknown to the defendant.

Note

You're not a digital imaging expert, nor do you want to possess contraband. Inspect the log files detailing dates and times of file uploads or downloads, file sizes and access dates, locations of files and how they were stored, and password protections to form an opinion regarding whether someone or something other than the defendant could have led to the images being stored on the hard drive.

You should also suggest a conference call with the lawyer and client. You have to ask questions about computer use (for example, times of day and Internet habits), user access, password sharing, and issues related to the circumstances. If that's not an option, discuss the possibility of e-mailing questions for the client to answer.

Being a computer forensic investigator means never saying "I can't find the computer file." Follow these steps to get organized:

Create a cases folder.

Give it a memorable name, such as

All CF Cases.Create a case folder for each case inquiry, which becomes your case folder if you get the case.

All case folders are nested within the

All CF Casesfolder. Folder names should include the case name (Plaintiff v Defendant), the lawyer's name, the month and year, and a descriptive identifier — for example,Acme v Zena Robson July 20## NY fraud case.Save a copy of every e-mail sent and received about the case.

Use descriptive filenames. Cases tend to span long periods, and people forget what was decided or communicated. When a call comes in from a lawyer who needs to discuss a case, you can easily find it later.

Scan paper documents and hard copies into the appropriate folder.

You may receive hundreds of pages of texting, e-mail, depositions, affidavits, and reports. An affidavit is sworn testimony. Keep these documents organized and protected in a filing cabinet so that they stay "clean." You may need to use them in your deposition or in court. Coffee or spaghetti stains send an unfavorable message about you.

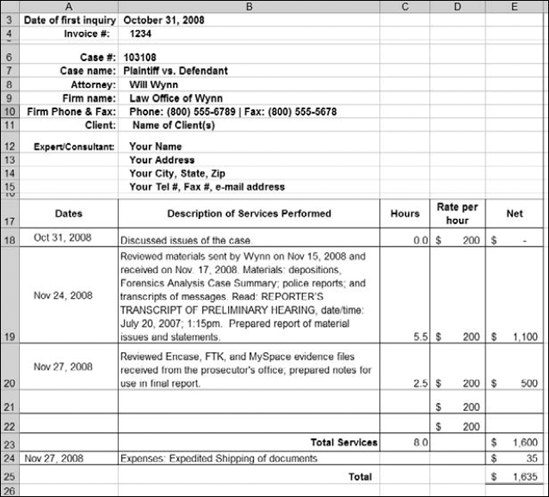

Create a spreadsheet template for tracking timeframes and descriptions of your work.

Starting with the first call, use the template to start a tracking file. Track the start and end times and dates of everything. Include everything even if no charge is associated with the activity. For example, list the first call for consultation and mark it No Charge. Figure 5-1 shows a spreadsheet you can design to track your activities. Include all details, which you can edit before submitting it as your invoice for professional services. After using your tracking spreadsheet as your invoice, start another tracking sheet in the same workbook so that you don't accidentally double-charge.

You want basic knowledge about the parties involved in a case, similar cases, or characteristics of the crime or lawsuit. The military calls this process intelligence. Doing research is necessary, is a slow process, and may be frustrating. With practice, you get good at it, so do research for every case to keep sharp.

Note

Don't bill for research you do to get up-to-speed on general issues.

Your search strategy includes several tools:

Search engines: For specific topics or companies that are new to you, start with a search engine, such as Google (

www.google.com) or Yahoo! (www.yahoo.com) to pick up background information and ideas for more precise searches. Your results will form the equivalent of a data dump.Try a search on exactly the phrase you're thinking about. For example, a search on how to defend against charges of fraud or electronic evidence in divorce cases may result in some useful information or threads. If you need to search for information about child pornography, do it very carefully, by using related terms, such as prosecuting child exploitation crimes. Search engines don't know your intent. Engines cannot distinguish between someone trying to research the crime and characteristics and someone looking to find and download contraband images.

These two examples show what you can learn from research into the use, or attempted use, of e-evidence in divorce proceedings:

In Florida: A wife installed spyware on her husband's computer and later tried to use the information she collected in their divorce case. The e-evidence was inadmissible because Florida bans the interception of communications.

In New Jersey: A wife was granted $7,500 during divorce proceedings after her husband wiretapped her computer to keep track of her transactions and e-mails.

Government agencies: Use the search engine to find

.govWeb sites. The U.S. Department of Justice (www.usdoj.gov) and the National RCFL program's Web page (http://rcfl.gov) offer up-to-date cases and Webcasts.LexisNexis or Westlaw online database (for-fee services): If information exists, it's probably accessible from these online services. Current news, business information, company directories, trade journals, federal and state laws and regulations, legal cases, and medical references are available at an incredible level of precision. Training is required, or else you waste time and frustrate yourself. For intense research, these databases are indispensable.

Legal encyclopedias and dictionaries: Find good, practical information that you can use to quickly look up a term or verify that you're using or spelling a term correctly.

Law school libraries: An amazing amount of law school content can be understood by nonlegal minds. And, the sites have search engines so that you can get in and out quickly.

Digging is the process of searching for information about a party involved in a case. The following list describes not only places to dig for information but also how a person leaves digital traces. Because the mantra for many of these social networking sites is "Find and get found," the search engines provided at each of these sites make searching for what you need quite easy.

Social networks, such as MySpace (

www.myspace.com) and Facebook (www.facebook.com): Typically, a MySpace user's Web page can be viewed by any other MySpace user. Further, any MySpace user can contact any other MySpace user by using internal e-mail or instant messaging on MySpace. Access to private text messages among members is available to law enforcement officers who have subpoenas. Confessions and admissions made while texting have been hard to refute and have even destroyed alibis.Video-sharing sites, such as YouTube (

www.youtube.com) and VideoEgg (www.videoegg.com): People post evidence of their crimes in public. In fact, UK police officials monitor YouTube for evidence of crimes. Several incidents of videos posted to the site have led to arrests. In many cases, perpetrators of illegal acts filmed themselves and then posted material to the Internet. Showoff videos aren't sufficient on their own, but they provide a good start or boost to the case.

No matter which side you're on (prosecutor/defense or plaintiff/defendant), you have to defend your methods, interpretations, and conclusions.

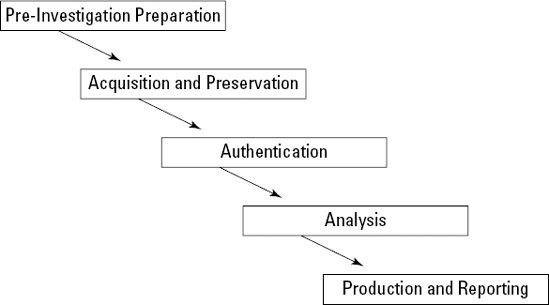

Maintaining the integrity of e-evidence requires a standardized defensible approach to data handling and preservation. Figure 5-2 shows your target — admissible evidence that isn't excluded because of a rule or loophole.

The opposition tries to find mistakes in your approach. Your defense, discussed in detail in Chapter 7, is that you

Acquire the e-evidence without altering or damaging the source.

Authenticate the acquired e-evidence by verifying that it was the same as the original.

Analyze the data and files without altering them.

Also, as part of your defensive strategy, your work is

Performed in accordance with forensic science principles

Based on current standard best practices

Conducted with verified tools to identify, collect, filter, "tag and bag," store, and preserve e-evidence

Documented thoroughly and in detail

Any wrong action you take can possibly blow out a case. Figure 5-3 shows the standard processes you should perform during your forensic examination. You see these forensic processes in action throughout Part III.

The key to effective data searches is to prepare and plan carefully. Quite simply, poor preparation can lead to mistakes or compromises or other compensations. Take time to understand and carefully plan which information is critical to an investigation or case.

Before acquiring potential e-evidence, you should do some fact-finding:

Interview members of the IT staff.

You need to find out how and where data has been stored. Though helpful, many times such a conversation with these people may be inappropriate. Have this conversation with caution. You don't want to tip off unauthorized people about the investigation, especially in a corporate environment.

Identify relevant time periods and the scope of the data to be searched.

You use this information to define and limit the scope of your investigation of the e-evidence. You want to be sure to cover the entire period and not waste time reviewing irrelevant materials.

Identify relevant types of files.

The case may not involve every type of file. Some investigations pertain only to documents, images, music files, or e-mail. Obtaining this information saves time.

Identify search terms for data filtering, particularly words, names, or unique phrases to help locate relevant data.

Filter out irrelevant information. Metadata can help in the filtering process.

Find out usernames and passwords for network and e-mail accounts.

To get past password-protected files and accounts, you may need this information. Password-cracking software is part of most computer forensic software packages, but cracking can take a lot of time and isn't always successful.

Check for other computers, devices, or Internet usage that might contain relevant evidence.

Ask questions about each of the other potential sources of useful evidence. People involved may not know that handheld devices, flash drives, or social networks are sources of e-evidence.

Warning

Document only the facts. Don't treat documentation like a diary of your thoughts or gut feelings.

You cannot work with the original material, so you must create an exact physical duplicate of it. The creation of a forensic copy is the acquisition. A forensic copy is the end-product of a forensic acquisition of a computer's hard drive or other storage device. A forensic copy is also called a bitstream copy or image because it's an exact bit-for-bit copy of the original document, file, partition, graphical image, or disk, for example. All metadata, file dates, slack areas, bad sectors — everything — are the same in the image as in their original forms.

Acquisition isn't the same as copying files from one medium to another. You cannot use a Copy command because dates aren't preserved. Make a copy of a .doc file on your computer; and compare the time stamps for the files. Notice the differences. Using normal operating system utilities to make a copy is a mistake.

Tip

Make several forensic copies in case something happens to the image.

A drive can be imaged without anyone viewing its contents. You can make a forensic copy in several ways, all requiring specialized software. This list describes two imaging methods:

Drive: This means of evidence preservation captures everything on a drive. One method of capturing or copying all data on a drive is to make a non-invasive mirror image of the drive. Slight variations in definitions of a mirror image exist. A mirror image might be an exact copy of a hard drive, but not necessarily. Mirror images are meant for backup purposes. To be safe, assume that a mirror image isn't a forensic image.

Sector-by-sector or bitstream: This more advanced method starts at the beginning of a drive and makes a copy of every bit — zeros and ones — to the end of the drive without in any way deleting or modifying the contents of the evidence. The file slack and unallocated file space that often contain deleted files and e-mail messages are acquired too. This method creates a forensic image of the e-evidence.

Failure to authenticate a forensic image may invalidate any results that are produced. Creating a forensic copy with the FTK Imager or EnCase tools authenticates the image. These programs store a report that includes two digital fingerprints, called MD5 and SHA1 hash values, that uniquely identify and authenticate the acquired data. Hash values enable you to prove that the evidence and duplicate data are identical. If data was altered, the hash values would also change.

Authenticating e-evidence also requires you to demonstrate that a computer system or process that generated e-evidence was working properly during the relevant period.

Your methods of analysis depend on which type of forensic you're performing — computer, e-mail, network, PDA, or cellphone, for example. A forensic image is, in effect, a single file. This handy format lets you perform keyword searches to find information or review thumbnail-size pictures that had been on the original hard drive. To survive an opponent's challenges:

Use analysis tools according to the manufacturer's directions or recommendations.

Test or verify that the results of the forensic tool are consistent before using.

If you use a generally accepted forensic toolset, these verifications are carried out for you, but you need to know what the software is doing.

You need to produce your results or findings to your client or the court. Working with your client to determine the design and content of a report is smart and helpful.

Note

Your reports aren't intended for all to see. Work on a need-to-know basis, and don't give or show the report to anyone without approval.

You can submit reports on a CD or DVD with hyperlinks to supporting information that's contained on the CD/DVD. This effective, self-contained method lets you concisely deliver the report and supporting information.

Writing that is logical and organized and that uses proper grammar, capitalization, sentence structure, and punctuation has become an ancient or arcane art. But try to recall a time when sentences were used. Resist the urge to use slang. Your results can be improved if you

Write the 1-minute sound bite story.

No matter how complex the issue, the news media delivers it as sound bites. You have to do the same. Think of your summary as a story. If your story doesn't persuasively explain why your opinion is reasonable, keep working at it.

Test your explanations and summary.

Be sure to test your story on people who are unfamiliar with the case and are technology-illiterate. If they think that your analysis is reasonable, you're headed in the right direction to persuade a judge and jury.

Writing a report takes time, concentration, and lots of editing. Leave enough time to write your report. Keep in mind that you use your own report to refresh your memory about what you did. Be good to yourself by minding the details.