In This Chapter

Delivering value to the case

Finding order in the court, and disorder in the court

Exhibiting e-evidence

Speaking to the judge and jury

In this chapter, we focus on you in the courtroom. In court, you have two influential roles — present e-evidence and testify as an expert witness. What you have to do depends on whether you're working for the prosecution, plaintiff, or defense or acting as an officer of the court as a neutral expert.

The party that has the burden of proof — and that party's computer forensics expert — tends to have the most work to do. Why? Because the justice system says "He who asserts must prove." That's legal language for "Put up or shut up." The court system puts the burden on the prosecutor or plaintiff to present sufficiently persuasive evidence and testimony to support the material facts. If that hurdle isn't met, the defendant's motion for a dismissal of the case may be granted. Evidence puts heinous criminals in jail, but wrongly used evidence can put an innocent person inside instead.

A huge number of cases end up in court. Yet they represent 5 percent or fewer of the total number of cases that are filed, because most cases are resolved by pretrial (see Chapter 15). For cases that reach trial, you need to be armed and prepared for the court's "barroom brawls."

In this chapter, we start with what is expected from you. (Hint: It's not a forensics image.) We explain court procedures regarding rounds of testimony. You find out the don'ts and do's of presenting persuasive proof and surviving tactics under rapid-fire questioning from opposing counsel.

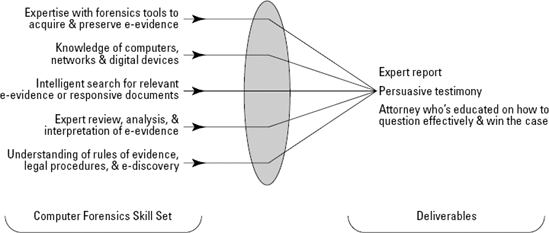

Why is an investigator part of the team? Think about why you were retained as a computer forensics investigator. If your reasons are listed on the left side of Figure 17-1, you bring those skills to the job, although they don't do you much good in court. Lawyers want you to help prove their cases or defend their clients. In a word, they want deliverables, things produced as a result of the investigation that they can use. Deliverables are listed on the right side of Figure 17-1.

You're brought into a case for your reports and testimony to persuade a judge and jury toward a particular way of thinking. If a defense lawyer needs you to shoot down a time- and location-based alibi that the accused gave in a deposition, that's what you bring to the trial. For example, your testimony might include these elements:

Cellphone records identifying precise times, numbers, duration of outgoing and incoming calls, text messages, and even calls to voice mail (VM).

Lists of name on phone for each telephone number listed as incoming or outgoing.

Transcripts of text messages sent and received and images found on the smart phone.

E-mail records and transcripts of messages.

Printouts of pages from online accounts showing the full transcripts of all messages sent and received — with names, images, dates, subjects, and incriminating content in an easy-to-read format.

Another deliverable is the ability to educate the lawyers about which questions to ask so that they know how to question — or corner — others effectively to best represent their clients. E-evidence is good at catching someone in a lie. You help prepare the catch and turn it into a story for the jury. Juries remember stories more than sterile facts. Every computer and handheld device has in it a story of someone who is a suspect. You bring that story to the courtroom.

In this section, you see how the adversarial court system works with and against expert witnesses, and you see the challenges of courtroom procedure and its drama. The system is highly structured. According to the Constitution, suspects are presumed innocent until the judge or jury decides that the evidence says that they're not. Then an appeal process takes place if the jury finds someone guilty.

Trial scheduling isn't precise. To be as efficient as possible, and recognizing that many cases are settled on the courthouse steps, courts schedule many different trials on the same date. If too many cases remain, some are rescheduled to a new date.

The courtroom can be the setting for rather interesting or mind-bending legal disputes. Issues that don't seem worth arguing about can involve the justices of the Supreme Court. Other issues about evidence can be resolved by simply having each side stipulate (agree not to disagree) that something is a fact. The court may have to agree on the stipulation — for example, the prosecution might get the defense to stipulate that a piece of evidence is admissible. Don't expect to understand why issues are or are not argued.

For issues that aren't resolved before trial, here are three reasons for disputes (only the last two involve the investigator's work):

Legal issues: Legal loopholes, or novel situations for which no case law or precedent exists. Basically, legal issues are about whether a crime has been committed. Consider this mind-twisting instance: If an adult in a private chat room performs a lewd act in front of a Webcam in view of someone whom the adult believes is a minor but who is in reality another adult, is this action a crime? Does it violate a law against public obscenity or harming a minor or someone else? This situation raises legal issues, not evidentiary ones (at least not until the legal issues are straightened out). Legal issues might concern whether the chat room qualifies as a public place or whether a minor child was in view of the computer.

The responsibility for resolving such issues rests with the courts, thankfully. A case you're working on might involve unique legal issues because the Internet and wireless technologies enable situations not well defined in the law.

Note

Judges decide questions of law.

Evidentiary issues: Disagreements over the e-evidence, such as its authenticity or interpretation. See the following sidebar "Disputing e-mail admissibility" for an example of an evidentiary issue in a fraud case. Expect to be knee deep in this type of issue given the many rules of evidence that can lead to disagreements over what's allowed and what's not.

Evidence that's presented as scientific by expert witnesses may seem subjective to the jury when it's challenged as an interpretive art by defense lawyers or their experts. Being too smug or complacent makes you less sharp.

Note

Never overestimate the strength of your e-evidence.

Technique or procedural issues: Lapses in the chain of custody, poorly documented e-evidence collection techniques, or an investigator's lack of credibility. Advanced law enforcement procedures for handling e-evidence, following the chain of custody, and performing proper forensics imaging make these issues rare. To verify, check the RCFL Lab Web site at

www.rcfl.govand review its ongoing investigations atwww.rcfl.gov/index.cfm?fuseAction=Public.N_investigations.Determining what the e-evidence proves is a job for the jurors. Your job is to persuade jury members by making sure that they understand what the e-evidence does or doesn't mean, what your inferences and opinions are, how you derived them, which possible flaws exist, and why those flaws are of no consequence.

You don't get to sit on the stand to give testimony about your investigation and findings and then stand down. After you take the stand, you're in play (so to speak) for several rounds with both lawyers. Keep this perspective in mind — your testimony gives the opposing lawyer an ice pick to poke away at you, your work, and your conclusions. Supposedly, badgering witnesses isn't allowed, but lawyers get away with it unless the judge decides to stop it. (There's a reason that those cruel-but-true lawyer jokes are passed around.) You don't get to object to any question or claim foul play. Only the lawyers have that kind of power.

Courts have a procedure for everything, including giving testimony. Not knowing those procedures or how to position your testimony for what's coming at you every step of the way puts you at a big disadvantage.

The timeframe for when you take the stand and testify depends on which team you represent. The following example outlines the process for giving testimony on the witness stand (plaintiff refers to the prosecuting, or plaintiff, lawyer):

Direct examination (also called direct) by plaintiff

The plaintiff calls its first witness (P-Witness #1) to introduce evidence supporting the allegations. Assume that's you. You're sworn to tell the truth, and then you answer the lawyers' questions from the witness stand. Because you're on the same team, you're treated well because it's presumed that you're giving favorable testimony. You should be prepared for this line of questioning. Here's an example of a direct question:

Q: Which personal accounting software did you find, if any, on the defendant's laptop computer?

Cross-examination (also called cross) by the defense

You're still P-Witness #1, but you're now questioned by the defense. Questions on cross are limited to the subject matter introduced during direct, which is generally a good thing. What's different is that the defense lawyer (who probably doesn't like your testimony) can ask you leading questions. Leading questions are in a form that suggests the answer to the witness.

Here's an example based on the question posed in direct examination if you had answered Yes:

Q: Is it true that you found QuickBooks accounting software on the defendant's laptop computer?

If you had answered No, the leading question could sound like this:

Q: Is it true that you did not find QuickBooks accounting software on the defendant's laptop computer?

Courts permit leading questions on cross, on the assumption that the cross-examiner needs to suggest answers to the witness in order to explore adequately the reliability of the direct examination and the credibility of the witness. During cross, the lawyer tries to undermine or impeach your credibility or attempts to show that you're not reliable, to create doubt about you in the minds of the jury members.

Warning

Never underestimate how high the stakes are during cross. Everyone familiar with the courts has seen cases won almost entirely because of the skillful use of cross or essentially lost because of a bungling or overconfident cross-examiner.

A leading question can be tricky when the lawyer deliberately tangles it up with a misstatement, such as this one:

Q: You told this jury this morning that, in your opinion, the images found on the defendant's laptop computer hard drive could have been downloaded to that hard drive by anyone who had access to the laptop, didn't you?

When faced with a misstated leading question on cross, you should

Deny the misstatement.

Restate what you had said.

Assuming that you had not made such a statement to the jury, your answer might be, "I did not say that. What I did say was that the laptop computer was password protected. The person who downloaded the images would have had to know the password or have been given access to the laptop by someone who knew the password."

The defense may decide not to cross-examine you after you give your direct testimony. That's usually a good sign because the cross mantra is "When in doubt, don't cross-examine." If you're not cross-examined, you're spared from having to experience Steps 3 and 4.

Note

If you haven't seriously harmed the defense's case or if the defense doubts that your testimony can be impeached successfully, cross doesn't take place. The defense doesn't risk damaging its case.

Redirect examination (also called redirect) by plaintiff

You're questioned again by the plaintiff about issues that were uncovered or that didn't go well during cross. You're back in friendly territory, so don't expect that someone will try to trick you.

Re-cross-examination (also called recross) by defense

Recross gives both sides an equal number of times to ask you questions. You face questioning again by the opposing lawyer if a redirect raises an issue that's leaving a bad impression with the jury. The defense has the chance to try to clean it up.

Steps 1 through 4 are repeated for any witnesses in addition to you until all the plaintiff's witnesses have testified.

Case rested by plaintiff

In this defining moment, the court is informed that the plaintiff rests its case. No more witnesses can be called to the stand or evidence introduced by the plaintiff.

(Optional) Directed verdict of acquittal

If the plaintiff hasn't proved its case, the defense may make a motion for a directed verdict from the judge. (The jury doesn't get to vote here.) If the judge agrees that the evidence is too weak, the trial is over. This verdict from the judge saves time and money because there's no reason to continue the trial if the case has already been lost. If the judge doesn't agree, the defense is entitled to present evidence, but isn't required to do so. Expect that the defense will continue.

Direct examination by the defense

The defense begins its direct examination with its own witnesses and evidence, with the roles reversed, until all defense witnesses have testified. If you're working for the defense, this step is where you first take the stand.

Cross by plaintiff

As in Step 2, cross-examination might not take place. If it does, you can expect the tactics discussed in Step 2 to take place. If not, Steps 9 and 10 don't take place, either.

Redirect by defense

Recross by plaintiff

All testimony ends. You're done, as are all witnesses.

Closing or final arguments

It's last call for the lawyers to influence the jury in this case. Your testimony might be mentioned here. No matter what's said about what you said, you remain silent.

Jury instructions

The judge gives instructions and charges to the jury, explaining the appropriate law and the steps they must take to reach a verdict. Your testimony may be brought up in these instructions. See the later section "Instructing jurors about expert testimony."

Jury deliberation and verdict

Jurors consider the evidence and reach a verdict of guilty or not guilty. In some cases, the jury doesn't reach a verdict.

Appeal

You may face examination as many as four times in court and under oath to tell the truth. You must tell the truth, no matter how damaging it might be to the case. Vigorous or harsh cross-examination, the presentation of contrary e-evidence, and careful instruction about the burdens of proof are the traditional and appropriate means of attacking shaky but admissible evidence. You find out how to give effective testimony in the later section "Presenting E-Evidence to Persuade."

Note

In 2008, John B. Torkelsen became a former expert witness after pleading guilty to perjury, a charge that carries up to five years in prison, for lying in court. Torkelson served as an expert witness for plaintiffs in hundreds of class action suits and shareholder actions against major companies, such as AT&T and Microsoft, that were litigated in U.S. federal and state courts. The law firms that hired Torkelsen told the courts he was an independent expert. Therefore, the law firms that hired him were precluded by rules of professional responsibility from paying him on a contingent basis — they couldn't pay Torkelson based on the outcome of a case. But several law firms secretly paid Torkelsen on a contingent basis and concealed the payment arrangement from the courts and defendants. He had made tens of millions of dollars as an expert witness in hundreds of lawsuits. "It is simply unacceptable for anyone involved in litigation to lie to the courts. Torkelson has compromised the pursuit of justice," according to Thomas P. O'Brien, the U.S Attorney in Los Angeles. For details, visit the US Department of Justice site at www.usdoj.gov/usao/cac/pressroom/pr2008/020.html.

The judge may instruct the jury specifically about your testimony. Here's an adaptation of the jury instructions from a New York court — you can download the PDF file from www.nycourts.gov/cji/1-General/CJI2d.Expert.pdf:

You might recall that [expert witness's name] testified about certain computer forensic and electronic evidence matters and gave an opinion on such matters. Ordinarily, a witness is limited to testifying about facts and isn't permitted to give an opinion. Where, however, scientific, medical, technical, or other specialized knowledge helps the jury understand the evidence or determine a fact in issue, a witness with expertise in a specialized field may render opinions about such matters.

You should evaluate the testimony of any such witness just as you would evaluate the testimony of any other witness. You may accept or reject such testimony, in whole or in part, just as you may with respect to the testimony of any other witness. In deciding whether to accept such testimony, you should consider these factors:

Qualifications and witness believability

Facts and other circumstances on which the witness's opinion was based

Accuracy or inaccuracy of any assumed or hypothetical fact on which the opinion was based

Reasons given for the witness's opinion

Whether the witness's opinion is consistent or inconsistent with other evidence in the case

Note

All along the way and right into the jury room, you are personally and professionally scrutinized.

Think back to your high school science or math class. After a topic became too complicated or drawn out, all you might have heard was a voice in the distance as your mind drifted away. Imagine a teacher explaining Newton's theory of gravity or geometry using formulas — without pictures or diagrams. Could you have assessed the truth of those lessons? If not, then you understand why you may need to use visuals in your testimony. Human attention is limited and tough to hold on to.

The jury isn't sitting in its box by choice. Jurors may be committed to their civic responsibility, but there are limits to what they can absorb and remember. Help them out: Plan, prepare, and present visual aids to make it easier to grasp, believe, and remember your e-evidence. The best way to represent a complex topic is with simplicity. Simple illustrations work best because they create fewer distractions for viewers. Although too many possibilities exist to consider for the design of your presentations, you can avoid certain risks when you use technology to present e-evidence.

Relying on computer technology, wireless connections, or electronics to work precisely the way you need them to at the moment you need them to is outright dumb. You can minimize disastrous moments by following these guidelines:

No surprises: Don't surprise the judge or your opponent. Get permission before trial for your demonstrations or presentations and the equipment you need for them.

No live events: Don't rely on anything live, such as a live Internet connection, Web site, or chat room. Use screen captures and label everything so that you don't have to rely on your (live) memory.

No ad libs: Don't expect things to work unless you've rehearsed and tested them yourself. If someone prepares a slide presentation for you, test it. Verify that none of the slides was accidentally hidden. Slides with swooshing sounds, poorly picked colors (no yellow, pink, vibrant turquoise or magenta because those colors can be extremely difficult to read and may look horrible if they're paired with other colors incorrectly!), or sideways or illegible text are tough for anyone to endure. Know how to use the software or device. You don't want to look like you don't know how to use computer equipment.

No epics: Consider the attention span of jurors. Too much detail can mess up the major points you need to make. Keep it simple.

No gaps: Connect the dots for the jury. If you're presenting a series of events, walk the jury through them. Create time maps that explain (lay out) events that are linked, such as showing the timeline of files that were downloaded and then copied to another media and then deleted.

No-tech backup: Expect problems and plan alternative displays as backups.

No forgetting all items you need. Think out every possible "oops" and find a solution for it. Similar to showing up at a crime scene to collect and capture e-evidence, you need equipment to display your e-evidence to the jury, and someone's budget determines what that equipment is. Bring extension cords or power strips. If you need to use a whiteboard, buy brand-new dry erase markers of the appropriate thickness.

Warning

Before any exhibit is admitted into evidence, the defense has the opportunity to challenge it. Prepare hard copy (printout) binders containing all exhibits to show to whoever needs to see them for review or approval.

Design your exhibits as simply as possible. If you need professional help with the design and creation of exhibits because you're artistically tone-deaf, find the help. You need to inform, not impress, but there's no excuse for low-quality or sketchy work. Consider these other tips:

Use terms that nontechnical types can understand, unless precision is necessary.

You don't want to call a forensic image a "copy of the hard drive."

Use analogies to explain complex technical material.

IP addresses may be tough for nontechnical types to understand, for example, until you explain that they work similarly to phone numbers. Explaining e-mail headers and delivery by relating them to physical mail is a simple but effective analogy.

Be prepared to explain and define technical material.

If the opposition tries to show that you're not such a helpful expert, you'll be ready.

If you're allowed to, stand up and point to elements on the exhibit to ensure that everyone is looking at the right spot as you describe it.

If you can't point, have someone on your team do it. As an element of the exhibit is being pointed out, describe what it is or its specific location so that the court stenographer can capture it in the transcript.

Don't forget that your attention belongs on the jury and not on your displays.

Ask jurors whether they have any trouble reading exhibits and give them enough time to read. If one of them has a problem, fix it.

Never testify beyond your expertise.

Exhibits must fall within your area of expertise.

Note

"Every contact leaves a trace." This statement is the basis of Locard's principle. In the early 20th century, forensic science became a specialized profession. Experts working in labs tried to link suspects to crime or crime scenes definitively. The scientist Locard recognized that "physical evidence cannot be wrong, it cannot perjure itself, it cannot be wholly absent. Only human failure to find it, study and understand it, can diminish its value." Because of Locard, the statement "Every criminal leaves a trace" became a cornerstone of police investigations.

Good testimony feels natural and flows well. When your testimony is being ground up by opposing counsel, you feel that too. The best expert witnesses persuade the jury by artfully and simply communicating the facts through reports, exhibits, and testimonies.

Warning

After being hired as an expert, all your materials or work product — analysis, notes, reports, correspondence, opinions, research — are subject to discovery. Be very careful with your work product practices to avoid creating misleading materials that can be used against you during testimony.

Beyond technical skills, lawyers need experts who testify well and are credible and likable to juries. Your opinion may be perfect but worthless if you can't persuade anyone to believe or understand that opinion.

Giving oral testimony is much less tricky if you know the rules. The following tactics and techniques can help you perform well during direct and redirect, and make you resistant to cross and recross attacks:

Compose a logical and focused testimony outline of the facts in the case.

Make sure that this outline is relevant to the opinions and is easily understood.

Prepare testimony that the judge and jury will believe.

If you don't believe it, don't try to sell it.

Establish rapport with the judge and jury by making eye contact with them.

Think of yourself having a conversation with the judge and jury when explaining methods and opinions.

Don't spar with the lawyers.

Be pleasant and patient no matter how hard it is. Juries react to you more favorably if you remain calm, answer matter-of-factly, and avoid clenching your teeth.

Be as natural and relaxed as you can be.

Don't look rehearsed or mechanical because it hurts your credibility. If you're stressed over not being well prepared, at least look relaxed.

Be aware of your body language, facial expressions, eye movement, and good posture.

Death-ray stares at the person causing you pain will be seen by the jury. Be prepared for a sneeze or cough.

Watch the jurors to determine their level of understanding.

If they look bewildered, change your pace or use more analogies or recap, if possible. Connect the dots with simple explanations of each step or e-evidence item.

Focus on the right thing.

Focus on the question that's being asked rather than on wondering what the lawyer is up to or where the questioning is headed.

Don't get misled.

If you're asked a hypothetical question, first consider whether answering it is smart or risky. If it's too complex or strange, respond with "I would rather not speculate."

The objective of giving testimony should never be based solely on winning the case.

Your credibility and qualifications are on trial too. Qualifications are skills and knowledge from education or experience.

You may be asked to discuss your earlier testimonies, state how much you were paid or charged, describe how you keep your expertise up-to-date, or explain other issues unrelated to the case being tried. Juries pay attention to your answers.

Avoid these mistakes:

Not being familiar with the facts of the case.

Not being prepared to defend your methodology and aware of its limitations.

Billing for work you weren't authorized to perform by the lawyer or client.

Charging too much or too little.

Not getting paid until after you testify or being paid based on the outcome. Payment issues are more serious than you might expect. See the later section "Getting paid without conflict."

Having a conflict of interest. Before accepting a case, you must verify that you have no conflict of interest (a situation where you can't be unbiased for any reason). The penalty for acting as an expert in a conflict of interest includes being disqualified from testifying, which could destroy the case.

Being inconsistent or giving a report or testimony that contradicts earlier reports or testimonies — in effect, fitting testimony to the theory of the case or to favor the side you represent.

Not identifying all the time spent examining the e-evidence. Your bill shows the amount of time you spent examining the e-evidence. If that length of time is significantly shorter than the time the opposing side's expert spends, it may lead to a charge that your opinion lacks sufficient basis. The opposite can be an issue too.

Stretching the truth.

Speaking to or on the media about a case, which can indicate that you're on the case for fame or other personal gain.

If you create an invoice for your services using a spreadsheet, such as Microsoft Excel, check your work. Dates, hours worked, and services performed must be accurate. If you format hours worked as currency or dates are changed because you copied them to another location, you create mistakes. Formulas or functions used in calculations must include the correct range of cells. How would you explain charging for services on the wrong dates or a total bill showing that you overcharged because of the wrong cell range? If you send multiple invoices, be sure not to double-charge.

A federal rule allows lawyers to pay a fee for the professional services of an expert witness. Having such a rule may seem ridiculous, but the history of the rule isn't important — only the rule is. The process of getting paid isn't written into the rule.

All parties need to be careful and precise with this payment issue because

The lawyer needs to avoid any action or expense that can lead to disputes between himself and the client over fees.

The lawyer and the client need to avoid disputes with the expert witness.

The expert witness wants to maintain an unblemished reputation by not "stiffing" the lawyer or client.

Suppose that an expert witness is retained by the lawyer, who intends to pass along the expert's bill to the client for payment. The expert is paid based on an hourly rate. This type of arrangement needs to be written into some sort of signed agreement. Why? Assume that later, after work has been performed, the client decides that the fee for the expert's services is too high — and shouldn't get any higher. Then what? The dispute over fees or payment could turn into potentially damaging testimony if it's not resolved before trial. Everyone could get harmed as a result.

Here are some common-sense recommendations for minimizing conflicts and disputes:

Use a detailed written fee agreement with the expert together with an engagement letter.

Having a fee agreement ensures that all parties clearly understand the arrangements — who and when — under which the expert is paid.

Discuss specific provisions for the withdrawal of the expert before the agreement is signed.

Include provisions in the engagement letter or fee agreement.

Warning

You cannot have an agreement with an expert that requires payment of a fee only for testifying in a certain way or only if the outcome of the case is favorable to the client.