In This Chapter

Appreciating the art of investigation

Facing investigative challenges

Preparing search terms and keyword lists

Judging smoke and mirrors

Doing an analysis

Reporting

Digging through a suspect's data, documents, memos, e-mail, instant messages (IMs), Internet histories, financial files, photos, and other information is what most people think of when they hear the term computer forensics — and for good reason. What you've done up to now, (getting subpoenas, lugging computers back to the lab, preserving evidence) has been in preparation for this big event — examining the e-evidence and figuring out what it says.

The stage is set. You made forensically sound images (see Chapter 6). What you have now is a forensic image (forensic copy) of each device to review and analyze. For evidentiary purposes, the images are on recordable-only CDs or other read-only media to retain the exact information that's copied and nothing more.

Examining e-evidence marks a shift from the science of forensics to the art of investigation. It's a demanding art. No technology or artificial intelligence exists that can pick up the scent and assemble clues, test theories, follow hunches, and interpret e-evidence. Human intelligence and determination are needed to find e-mails or files that are smoking guns of guilt or white knights that exonerate.

In this chapter, we explain the e-evidence examination process. Your objective is to search for and analyze the facts in full, interpret what they do (or maybe do not) mean, and present your findings without judging what you found. Expect to defend the actions you did and did not take, the inferences you drew, and any limitations of your search tools or methods under unfriendly crossfire in court possibly years later. Obsessively document everything as though the case depends on it.

Scientific inquiry is a process that's more art than science. It calls for rational and creative thinking, for which (most) humans still retain the exclusive. Computers can't think, fortunately. Imagine squaring off against HAL from 2001: A Space Odyssey or Gort from The Day the Earth Stood Still.

Acquisition and preservation make up the technical side of forensics. After the forensic images are properly made, you have a big pile of evidence, an unknown portion of which is relevant to the case. When you have a lot of e-evidence (for example, five 120GB images), a thorough file-by-file search of each image can't be done: Your available time and sanity won't allow it. It would be similar to making a door-to-door search of an entire city to find suspects — it's not possible, or at least not practical.

Although you develop your own strategies to deal with cases, the way you navigate the examination typically goes like this:

Ask questions and observe as much as possible.

Examinations shouldn't be scavenger hunts, but they can be if you can't get answers to your questions. If you don't already know (if you haven't been involved from the outset), ask questions to gain a fundamental understanding of the elements of the case, e-evidence, chain of custody, and actions that are expected of you. Whenever possible, try to interview the person you're accountable to and the person whose data and files you're about to review. An interview is a conversation with a purpose. Your purpose is to get information.

Design your review strategy of the e-evidence, including lists of keywords and search terms.

When you learn about the case, decide how to allocate your time and effort. You may need to become familiar with or focus on images, and then e-mails, and then Internet viewing history. Search terms are discussed in detail in the "Getting a Handle on Search Terms" section, later in this chapter.

Review (examine) the e-evidence according to the strategy you designed in Step 2.

This is the main event. Execute your strategy, making adjustments as you discover clues to follow. Clues are like threads: You find a thread and then follow it to see where it leads. Clues may lead to locations or evidence not captured in the image under review. Follow up. (For more information, see the section "Looking beyond the file.")

Formulate explanations, interpret them, and draw inferences.

People are relying on you to explain what happened and how it could have or could not have happened, and to do so in a way that they and juries can understand.

Note

Be alert to the distinction between what you observe during your review and what inferences you make. In general, observed evidence can be viewed and verified by others, such as a specific e-mail found on the hard drive. But inferences are drawn based on how you interpret what you observe. Inferences can vary greatly from one person to another (such as when an e-mail shows abuse). The middle process, interpretation, makes your inferences more difficult to verify.

Reflect on your findings and your methods.

Does this step surprise you? We're basically telling you to sleep on it. Consider this period your timeout to review and consider the evidence you discovered. You're checking your work. Ask yourself questions about your methods, strategy, results, interpretations, and missed opportunities, for example.

Report on your findings.

Yes, we're talking about the dreaded topic of report writing. We recommend that you read about the specifics of clear legal writing in Paralegal Career For Dummies (Wiley Publishing).

Tip

These steps aren't completed in sequence. You may have to go back to an earlier step as you learn from the evidence. You might, while reflecting on your findings (Step 5) have an "Aha" epiphany moment and want to review the evidence again (Step 3).

You don't have an unlimited length of time to complete the analysis, either. Resource constraints will (and, typically, should) influence how much time you spend doing your work. You need to make inferences (Step 4) and base them on what you reviewed and analyzed (Step 3). You might not notice a gap until you're writing the report (Step 6). Go back because that gap is also a loophole — and no one — except for the opposing side — wants to hear that particular L word.

No analysis tool can interpret the e-evidence or provide the clues that link the e-evidence and elements of a case. You provide that expertise. In this section, we discuss the challenges that can add nonstop excitement to this stage of the investigation.

How well prepared you are to start looking for relevant evidence depends on multiple factors, some beyond your control. As in any other profession, you follow standard methods, keep up with your learning, and get better as you gain experience.

If you're a TV detective show fan, you see investigators facing a uniquely perplexing situation during each episode. But the investigators follow the same methods to solve each of their cases. Factors influencing the challenges you face are listed in Table 7-1. This list isn't exhaustive. You run into these factors in various combinations. Consider each combination a learning experience. To ease your pain, always view painful experiences as learning ones.

Table 7.1. Factors Influencing the Challenge of the Investigation

Your Role | Type of Case | Working Conditions | When You Got Involved |

|---|---|---|---|

To support plaintiff | Civil | Friendly | Before any legal action |

To support defendant | Criminal | Neutral | During e-discovery |

To serve as neutral party | Employment | Nonsupportive | During capture and imaging |

To investigate for a private party | Divorce | Hostile | During image review and analysis |

To investigate for a private party | Fraud | Stealth mode | Just before the trial began |

Here are four examples of situations you might face. (We already faced them, so we disguised them here.) In the last two examples, we also describe the analyses:

A hostile environment: You're hired by the plaintiff's attorney in a case involving the theft of engineering drawings by a former employee of a manufacturer. Management suspects that the employee gave copies of the drawings to his new employer, but no other information is given to you. You arrive on-site to capture files and e-mail from the suspect's office PC and network logs and to review them.

Immediately, the IT staff resents you for being there, because they were responsible for controlling access to confidential files and filtering e-mail — and they hadn't done so. Adding stress, the lawyer doesn't show up, so you're there alone; and the network had crashed that morning, so no one has time to talk to you. In this example, you're reviewing for the plaintiff in an employment case under hostile conditions after having captured the evidence yourself.

Stealth mode: The director of human relations (HR) hires you to inspect an employee's computer to find out whether the employee is violating company policy by viewing pornography. HR needs the investigation done without alerting the employee or anyone else. In this case, you work for a private party in stealth mode after 10 p.m., when the office is empty, to acquire the image, and then review it later, off-site.

Neutral environment: A defendant's attorney sends you a CD containing the image of his client's computer that had been made by law enforcement. You also receive

.xlsfiles listing details about cookies and recently used files. The defendant is alleged to have bought or purposefully downloaded child pornographic (CP) images — a criminal case.Review and analysis show the presence of a small number of possible CP images, all with file sizes smaller than 10 kilobytes (K), and most smaller than 5K. The file sizes indicate thumbnail-size images. What's also important is what there's no evidence of. (See the "Finding No Evidence" section, later in this chapter.) There's no evidence of typical indicators of CP behavior (for example, image files weren't organized; no bookmarks, usernames, or e-mail names indicating interest in CP; and no file sharing). The review shows many visits to adult pornographic sites (which is an objective observation that can be seen by others), at which time the CP thumbnails could have been downloaded unknowingly (which is an inference that is subjective and that another person may not agree with).

Friendly or nonsupportive environment: Just one week before the jury trial begins, a prosecuting attorney asks you to confirm that the suspect in custody had in fact sent e-mail threatening federal agents, which is a criminal offense. The threatening e-mails would corroborate other types of evidence (letters, faxes, and in-person threats). You ask the prosecutor these two questions, "How did you tie the e-mails to your suspect? How do you know it was him and not someone else who sent the e-mail messages?" But no one on the prosecution team can come up with an answer that would stand up in court. You proceed to do the analysis. E-evidence shows the e-mail had been sent from an account that the suspect used, but you cannot link the suspect to the messages. Prosecutors are spared making a mistake in front of the jury. The suspect was still found guilty because the e-evidence was correctly used to corroborate the physical evidence rather than to stand on it own. On its own, that e-evidence was insufficient.

Warning

In any type of case, the defendant may frankly admit that he's guilty. His lawyer may want you to analyze the data and determine how bad the evidence is against the client. You may be asked to make a judgment call on whether the client should take the plea deal. You're not a lawyer nor a judge or jury.

Because you can't read the image file by simply clicking it, you have to use forensic software to open the file. You can use forensic software to structure a query and catalog your results, but the final results depend on you. You need to know exactly how to do what you want to do.

Overall, you're querying the forensic image to discover what has happened and how it happened or could have happened. Querying is a structured search approach. Unless you have very few files or an infinite amount of time, your examination depends on your querying ability.

The effectiveness and efficiency of your searches improve the more you observe and understand the elements of the case, the characteristics of the crime, and the people involved. That's why you start the examination by asking questions. Use your knowledge to build the list of keywords or search terms to find respondent files.

It's not unusual that only a few responsive e-mails exist in a pool of many thousands. Even if you find every single one of those e-mails, you still can't be sure that you got them all. Unless you have the time and the attention span to read each e-mail, you use your judgment to determine that you've done a reasonably thorough search.

Tip

Be prepared to defend your search strategy by keeping a detailed explanation of your search protocols, procedures, search list, and tested hypotheses.

Keyword searching is a tricky process. You have to zero in on precise terms but not exclude necessary terms. And that doesn't account for human error in developing a keyword list.

In the following section, we discuss putting together search lists and then explain how forensic software can overcome some search-related limitations.

Note

Expect to make several passes through the image using various search filters. It's not likely that you can do a single search and retrieve all relevant files. You might find out something new from each pass.

Your search results depend on your list of search terms. You can reduce uncertainty by attempting to know as much as possible about these three Cs:

Characters: Understanding the people involved — the accuser and the accused — and their possible motives gives you context for the search. The cast of characters may be unique, but motives and tactics are not. Law enforcement is experienced and skilled in figuring out motives. It's not uncommon for a person to unfairly accuse another of harassment or fraud. It's too easy to frame others or attempt a cover-up using e-mail or forged documents.

Circumstances: A timeline of activities or surrounding circumstances can help identify the puzzle pieces and how they fit together. Ask for dates to narrow your search to events that fell within that range. Determine whether one party had physical or remote access to the other party's computer or e-mail accounts.

Characteristics of the crime or legal action: You need to know the possible interpretations of what you find. You may need to research the crime to understand its characteristics to draw inferences. Some crimes may be beyond your expertise or tolerance. For example, if you don't understand how accounting systems work and how fraud schemes are carried out, don't investigate fraud unless you're working with someone who does know.

You can also add search terms to your list during pretrial conferences and depositions:

Using Rule 16 results: Detailed information about characters, circumstances, and characteristics may also be available for you. Litigants hold a pretrial meeting to address e-evidence to better understand the opposing party's electronic data. From that meeting, you may get details such as the location, format, and status (active, archived, or deleted) of an opponent's data. (See Chapter 2 for more information about Rule 16 and pretrial conferences.)

The parties may have agreed to file extensions, keywords, metadata, or dates. For example, the parties may agree to a search for all e-mail containing specified search terms, keywords, or other selection criteria needed to narrow huge data sets to a manageable size. You can then limit the search-and-review process based on those agreements.

Using depositions: A deposition (or depo) is testimony under oath in the presence of a court reporter before the case gets to court, but not in court. Depositions are part of discovery. Attorneys may set up depositions to get sworn testimony from someone who knows something relevant to the case. Transcripts of depos are an excellent source of search terms, names, dates, and other information. You may get deposed as an expert, which you can read about in Chapter 15.

One of the computer forensic software kits, which may or may not have been used to acquire the image, is commonly used to search and identify files that you need to review. Search capabilities continue to improve, but tools themselves can't perform the review.

During the acquisition process, the software may have created an index of terms, which are basic units of a search. A term can be a single character or a group of characters, alphabetic or numeric, and have a space on either side. Indexing increases the time it takes to acquire the image, but it expedites the search.

Tip

Get trained in using the software before you use it. Keep a copy of the manual and refer to it as needed. Software versions change, so you should keep the manual for each version you use.

Two types of search options to use with your keywords or search terms are described in this list:

Broadening options apply to words:

Stemming: Searches for variations of the root of the search word; for example, a search for poison also finds poisonous.

Synonyms: Searches for synonyms of the search term; for example, a search for money also finds cash and funds.

Homonyms: Searches for words that sound the same; for example, manner also finds manor; and serial also finds cereal.

Fuzziness: Searches for different spellings of a word or misspellings; for example, lethal also finds lethel and leethal. Searching for flavor also finds flavour and flaver.

Fuzziness is useful for finding misspelled words or mistakes in numbers. For example, if you're searching for numeric references, such as product X7447, a fuzzy search would catch X7747 if that mistake had been made. You can specify the degree of fuzziness; 1 is the least fuzzy. If you're searching for the word subpoena, for example, use a high degree of fuzziness because that word is commonly misspelled. Fuzzy searching makes sense for first and last names, city names, company names, and other proper nouns.

Limiting options apply to dates and file sizes. You can specify

Data ranges for either the range of dates when the files had been created or when they were last saved (or both)

File sizes or a range of file sizes

Other keyword searching options may be available depending on your software. You can use various options in combination to extend the word search and limit the number of files. The broader your search filter, the greater the expected number of results. And, eventually, you need to read through your resulting list of files.

You can link search terms using connectors. You can use Boolean searching, as it's called, to develop a search expression to filter your results. If you understand how Boolean connectors work, you can improve or expedite your search by using these standard connectors between your search terms:

AND: Narrows your search by requiring that the file contains both search words. For example, the search for X7447 AND carbon produces only those files that contain both X7447 and carbon anywhere in the file. As a general rule, use AND when it doesn't matter where the search words appear in a file. If the search terms are fairly unique, the AND connector can find files related to your case.

OR: Expands your search by broadening the resulting set of files. Files that contain either search word or both words will be found. In effect, using the OR connector in a single search (for example, hydrogen or nitrogen) is similar to making two separate searches (one search for hydrogen and another search for nitrogen) at one time. You can broaden the search by increasing the number of times you use the OR connector; for example, hydrogen OR nitrogen OR carbon.

AND NOT: Subtracts files that have the specified word in them. For the phrase and not hydrogen, files containing hydrogen are excluded from the search results.

Note

When you use AND NOT, be sure that it's the last connector you use in the search expression. Everything after this operator is excluded from the search results.

You can combine these operators, but do so carefully because these tiny words are powerful. You might exclude files unexpectedly or create unintended results. If you use two or more of the same connector, they operate from left to right. An order of priority may exist: For example, if OR has the highest priority, the OR connectors are processed first and then the AND connectors.

Warning

After you put on a filtering operator, it might stay on even after you've started a whole new search. Check the directions in your forensic software for removing any filter you applied.

Each computer forensics software toolkit has its unique search methods that are based on the Boolean search. Check the software manual for its search features and tools.

Search engines and their options are based on assumptions. You make many assumptions in your career, or else you can't proceed. If those assumptions are wrong, the results are too, unless you're darned lucky. You make four main assumptions while searching:

The person writing the messages or documents didn't use slang or code words, possibly to avoid detection.

The evidence wasn't planted by someone else who managed to get access to the drive.

Any user of the computer hadn't visited a site that dropped or downloaded content onto it without the user knowing about it.

The computer hadn't been compromised by malware that left it vulnerable to use by others.

For these reasons, you need to do a direct visual inspection of the contents of the files on the image.

You can pick up clues by looking at thumbnail images or reading e-mails to use in keyword searches. It's an iterative process. What you discover by directly reviewing files can help focus your keyword search, and keyword searches can find files for you to review.

Forensic software enables you to view the contents of files even if they were deleted (unless the files were overwritten; see Chapter 1). The software also organizes the files according to categories or status, letting you choose to examine only these elements:

E-mail messages | Folders |

Documents | Slack space |

Spreadsheets | Encrypted files |

Databases | Deleted files |

Graphics | Files from the Recycle Bin |

Executables | Data-carved files |

Note

Data-carved files are files carved out from unallocated file space. Data-carving tools search unallocated space for header information, and possibly footer information, of known file types and then recovers that block of data. The files themselves don't exist, even as deleted files, so they must be carved out of that space. If you're interested in finding out more about data carving, visit the site of the Digital Forensics Research Workshop (DFRW), which sponsors forensic challenges as part of its annual conferences. The DFRWS 2006 and 2007 Forensics Challenges focused on data carvings, the results of which you can review at www.dfrws.org/archives.shtml.

A basic data-carving test created by Nick Mikus is available at http://dftt.sourceforge.net/test12/index.html.

You found the incriminating files. Hurray for you. Now move on to the report. Not so fast. Great detectives, like yourself, look for planted evidence and attempts to frame a client.

What would the investigators on the TV show CSI do when examining evidence and trying to interpret it? They would consider the following risks, and more, as they became apparent:

If your computer were forensically investigated, consider whether you would be willing to bet the farm that there's absolutely no evidence of wrongdoing on it. Unless your computer is brand-new, has never been used, or was never exposed to the Internet (all improbable situations), don't take the bet. You would be playing Russian roulette with no missing bullets.

Planting evidence to frame others can be done with e-evidence as easily as with physical evidence.

No malicious or deliberate attempts were made to personally implicate your client, but the client got caught up in the e-evidence. Here are some situations that can get out of control:

An employee quits and her computer is given to your client without being forensically wiped clean.

Your client buys a used laptop from eBay. All kinds of creepy crawlies could reside on that hard drive.

Your client has sloppy computer and Internet hygiene habits — or shoddy click-impulse control. Although it wouldn't always happen, the defense strategy "The malware did it" can be the truth.

Figuring out what happened is tough, but it's still easier than showing how it happened or who did it.

Finding planted evidence or attempts to frame others is tough. An important aspect is keeping an open mind. It's easy to make a mistake and stop the investigation after the evidence is found on the initial suspect's computer, but it may implicate the wrong person. You need to verify your results by trying to disprove them yourself.

Here are some verification tests to perform or questions to be answered depending on the elements of the case:

Follow the vendor's or manufacturer's directions regarding the use of the product. Chapter 20 lists the types of products used by computer forensic investigators.

Test the product or the results of using it before you use it on the evidence.

Check the target computer for the necessary operating capabilities or software to open or create the files. Finding Microsoft Word or Excel 2007 files, for instance, on a computer that cannot open those files raises a red flag.

Verify that the target computer is capable of viewing the pictures, editing the document, or printing it.

Make sure that the suspect's computer works and that all the drives work.

Verify which types and versions of e-mail and accounting programs, for example, were in use at the time.

Determine whether the suspect had access to the computer at the time that illegal files were downloaded. Verify that the computer's clock is set correctly and for the proper time zone.

Make sure that the programs or devices needed for exporting the suspect files are on the computer.

You find out how to search for and verify e-evidence in the riveting specialty forensic chapters in Part III.

It's tempting to do, but you cannot draw conclusions or make judgments outside your area of expertise. For example, you cannot judge whether a photo is child pornography or a spreadsheet shows hidden assets, because you're not an expert in that type of identification.

Note

No matter how obvious something is to you, stop and reflect on what you've analyzed.

You may find no evidence that something happened. Or, you may find no evidence that something did not happen. The case may depend on what you found no evidence of.

You need to report what you did not find. Someone will ask you about what you did not find. The following two sections show you two examples of what you need to report not finding.

Passwords do not authenticate who's logging in. After a username is entered, the system authenticates that the correct password for that username is entered. What do a username and password prove? Not much. They're supposed to authenticate who's logging in, but they don't. Unfortunately, password guessing, sharing, and findings take the air out of that evidence.

Who was logged on a computer at a particular date and time? Unless the computer is biometric-capable or clear camera images were captured, you cannot "connect the dots." If the computer is biometric-capable and the user made use of biometrics when logging on, you have traction. Biometrics can point the finger at the user logged in at a particular time, like the secret handshake to get let into a clubhouse. Biometrics uses an individual's physical characteristic, often a fingerprint, to authenticate that person for access to the computer. Typical biometrics, in secure facilities, include fingerprints or handprints.

You can report on which images you found in a file, but you might not be able to report on how the images got there. Likewise, finding supporting evidence in a user's browser history doesn't make the user guilty, although it can close the window of reasonable doubt a little.

Note

E-evidence may not prove that a crime was committed, but it can support motivation or intention to commit that crime. You know the drill. Be careful, exact, and don't jump to conclusions.

Reporting your findings is a critical element to your success as a forensic examiner. You cannot avoid reporting. No matter how whiz-bang brilliant you are as an investigator, if you can't write out your findings in an organized report that's easy to navigate, read, and understand, your forensic talents may get wasted. You may need to submit one of these items:

Working papers: Prepare your working papers in such a way that they're understandable to independent reviewers — juries, for example. From an efficiency perspective, consider that the purpose of a working paper is to document the procedures you performed and the conclusions you reached. Be neat. If the document you create is clear, accurate, and readable, it qualifies as a working paper.

Preliminary report: If your work involved data sampling or the attorney asked for a preliminary report, label your report as such. If your analysis isn't complete, do not label the report as final.

Final report: Consider submitting this report the same as testifying under oath, because that's where you may have to explain and defend it.

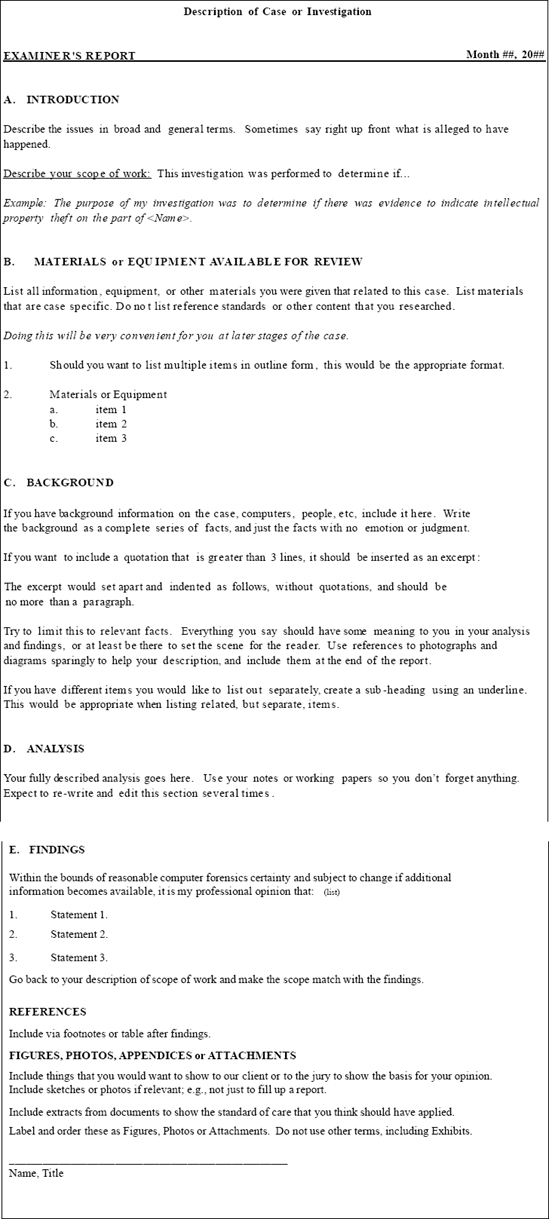

Figure 7-1 shows an example of the types of information in a report and the structure of the report.

Note

Be sure to spell check and proofread before you submit the report. Also, be sure to check and correctly fill in the properties of the document.