In This Chapter

Obtaining the proper authority

Covering all your bases

Putting your case together

You can get yourself into serious trouble or mess up an investigation if you bulldoze over the rules for search and seizure of e-evidence. You've seen crime movies where the dedicated detective — such as Dirty Harry or Andy Sipowicz from NYPD Blue — finds convincing incriminating evidence, only to have it tossed out because he didn't have the authority to make the search in the first place. That news is painful. You want to avoid the frustration of letting criminals go free because of a technicality surrounding your search. Worse, you can get into legal hot water if you throw away the rulebook and are found guilty of misconduct. Wrongdoers know how to manipulate the justice system, but you don't get that option.

Standing between you and the devices or information you want to search and seize is the Fourth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. It states that people have the right to "be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures."

The Fourth also says that search warrants must be approved by judges. A judge's approval depends on probable cause, which means that you're not on a fishing expedition for evidence. However, exceptions to the warrant requirement exist, such as consent to search, the plain view doctrine, and exigent circumstances.

In this chapter, you find out the rules about authority, their purpose in privacy protection, when they're in play, and exceptions to the rules. You're figuring out how to do things by the book — the law side of computer forensics — and will get a good feel for what Harry and Andy faced.

Understanding the technical side of computer forensic investigation is a commendable and daunting accomplishment, but you still have to learn the law. Legal requirements always come first. Don't touch that device unless you understand the law and its lingo so that you can investigate ethically and without putting yourself in harm's way.

Investigations are a team sport, so to speak. Even the legendary fighter of injustices, the Lone Ranger, got help from his partner, Tonto. In many cases, being the computer forensic professional means that you're the technical expert but not necessarily the lead investigator in charge. You may be and should be working with a legal expert who guides the team through the intricacies of legal traps.

Depending on the range and type of case — criminal or civil — you may need to get permission from more than one authority. You'll know the basics of subpoenas and search warrants if you read this entire book, but don't try to be a hero out in the field. Let law enforcement or legal counsel be the boss, depending on the type of case:

Criminal cases: The authority is exclusively the domain of government and is subject to a stringent set of rules.

Civil cases: The authority can be either the government (the attorney general, or AG, for example) or a private party, such as a corporation, and subject to lower standards for authorizing searches and seizures.

Using the team approach in civil and criminal cases increases the odds that procedures and reports withstand the scrutiny of the court and cross-examination by opposing counsel. If the opposing counsel is well prepared, it can be a tough audience and a capable opponent.

In a common criminal computer forensic case, you find three types of investigative team members:

Prosecutor: This attorney ensures that the team complies with all applicable laws and legal procedures before and during a search or seizure. Because the prosecutor appears before a court to litigate the case, he has a vested interest in making sure that the investigative team leaves no legal loophole that the defense team can walk through. Chapter 5 is dedicated to minding and finding loopholes (although loopholes are beneficial if you're the one finding and using them to your advantage).

Lead investigator: This person manages and coordinates investigation procedures and ensures that they're performed correctly. The person might not have technical expertise with electronic devices, but knows which information is useful and which is beyond the scope of the case. (You're working without a net if you go beyond the scope of the case!)

Technical expert: This computer forensics expert knows how to acquire, analyze, examine, and interpret electronic content so that it's incontestable in court — or at least as resistant as possible to being contested. This person is crucial to the lead investigator and prosecutor. You are likely this person.

Computer forensic teams in civil cases share the same basic structure as their criminal counterparts, but a more varied set of professions may be involved. In civil cases, bear in mind that although the standards may be lower, sloppy work always comes back to damage your case!

Civil case teams consist of these three people:

Attorney: Deciphers legal jargon and knows which policies, procedures, and laws apply to a specific case. In practice, expect to advise attorneys on more than just the technical aspects of the case. This area of law is relatively new, and you may have to point the attorney in the right direction regarding case law in this area. You depend on them to understand what must be done or not done to minimize liability. The attorney should know local rules and advise your team accordingly.

Case manager: Manages the case. The person filling this role varies by circumstance or according to who has requested the investigation. In all instances, this person is responsible for how the investigation is conducted. The case manager for a corporation may be a department head; for a college, a human resource representative; and, for a small company, its owner.

Technical expert: This person is the same as in criminal cases.

Note

You want to have a bulletproof case with incontestable e-evidence. Your goal is to complete the forensics analysis, pass your report across the table to an opposing counsel who realizes that your results are so irrefutable that your opponent must settle out of court or drop the lawsuit. No more time and money than are necessary are spent on pointless court trials.

The authority to conduct an investigation comes from different external sources depending on — you guessed it — whether you're working on a civil case or a criminal case:

Judges and magistrates: Given the high stakes of a criminal case, the authority to conduct searches usually comes from judges or magistrates. We talk more about requesting this authority in the section "Criminal Cases: Papering Your Behind (CYA)," later in this chapter.

Exigent circumstances are the rare exception. When law enforcement officials have a "reasonable" expectation that evidence will be destroyed or altered in some form, they have the authority to seize the evidence without a search warrant. But you had better be able to back up your actions to a judge or jury when asked why you seized the evidence without a search warrant.

Owners, managers, and supervisors: In U.S. companies, employees cannot claim an expectation of privacy as easily as their counterparts in Europe can. Managers, supervisors, or owners can give you the authority to search a computer. In some cases, co-worker authorization can provide access to data. An example is when management hires you because they suspect accounting irregularities and want you to find out what's happening. Because the search is private, the Fourth Amendment doesn't apply and you can proceed without a search warrant. We talk more about this kind of authorization in the section "Civil Cases: Verifying Company Policies," later in this chapter.

Warning

Don't rely solely on a co-worker who gives you authorization unless you already had the go-ahead from an owner or a senior executive to search and analyze evidence unless you have no other options. The co-worker may be trying to be helpful, but he may not have authority to give authority.

Licensing bureaus: Only rarely would you as a forensic investigator work as your own authority. Many states are now adopting rules putting computer forensic or data recovery services under new licensing guidelines. Some states are making it illegal to perform computer forensic investigations unless you have a private investigation license. States might allow exceptions if you're working under the authority of an attorney on a case specifically authorized by that attorney. This development is still new and changing rapidly because computer forensic professionals are questioning the need to be licensed as private investigators when other disciplines, such as DNA and crime scene forensic investigators, aren't required to be licensed private investigators.

A search warrant may not be necessary to conduct a search in any of these situations, but be sure to verify first, anyway:

Consent search: If an individual voluntarily agrees to a search, no warrant is needed. The key question is what legally qualifies as a voluntary agreement. For the search to be legal, an individual must be in control of the area or equipment to be searched and must not have been pressured or tricked into agreeing to the search.

Plain view search: An investigator spotting an object in plain view doesn't need a search warrant to seize it. To make the search legal, the investigator must have a right to be at the location, and the object he seizes must be plainly visible there.

Search incident to arrest: In situations when a suspect has been legally arrested, law enforcement officials may search the defendant and the area within the defendant's immediate control. For the search to be legal, a spatial relationship must exist between the defendant and the object.

Protective-sweep search: This situation is a series of two events. After an arrest, law enforcement officials may sweep the area if they reasonably believe that a dangerous accomplice may be hiding nearby. For example, police are allowed to walk through a residence and make a visual inspection without having to obtain a warrant. If evidence of, or related to, a criminal activity is in plain view during the search, the evidence can be legally seized.

Suppose that you want to convince the external authority in charge of a case that you should work on the case. In the case of criminal search warrants, the process is fairly formal and dependent on how you present yourself. Just saying to a judge, "I think they did something wrong" only irritates the judge.

The process is straightforward in that you present your reasons by way of an affidavit to the judge, and a search warrant is issued, which gives you permission to search.

You're the technical expert, but it's a legal game and you're not the referee. You have a certain amount of responsibility to ensure that your legal point person is doing the job correctly so that all your hard work doesn't end up being tossed out of court. If you're truly unlucky, you can end up in court defending your reasons for performing an illegal search.

To help you avoid that situation, we discuss in the following sections each of the steps you take to get that approval from a judge.

At the beginning of every investigation, verify that you're constructing a solid foundation of proper legal procedure. Without this defensive strategy, you

Waste your time

Allow someone to get away with a crime

Risk your reputation and financial well-being

Take these steps to learn about your case:

To make everyone's jobs smoother, ask questions about the type of information you're looking for.

The answers determine where you look, which tools you need, and which information you're not looking for. Make sure to get answers and write them down. If you're searching and seizing computers at a local bank, for example, here's a list of possible crucial questions:

Are you looking for financial or bank data or accounting ledgers? Or child pornography? Or a simple chat session?

Which operating system will you work with — Linux, Mac, or Windows?

Is a network involved? If yes, which type? Is it wireless or wired? Windows or Unix based?

Do you have numerous CDs to handle, or does the computer system have external flash drives?

Are passwords or encryption involved?

Identify the specific sources of e-evidence.

Consider whether the data is located on the network, computers, digital devices, or — in the worst case — on the Internet. (This is where your fun starts, depending on your sense of humor.) Each of these considerations affects your search warrant strategy.

Determine the expertise of the suspect or person of interest.

Warning

Don't overlook this step because you think that computer criminals aren't technically adept. Trust us when we say that certain users can run circles around some technical geniuses. Never underestimate the human factor. If the person of interest has some expertise, look at the investigation from "outside the box." Instead of just relying on the computer forensic software, you may need to either look at the evidence in a more technical way or even study the suspect's behavior to understand how they might have hidden evidence.

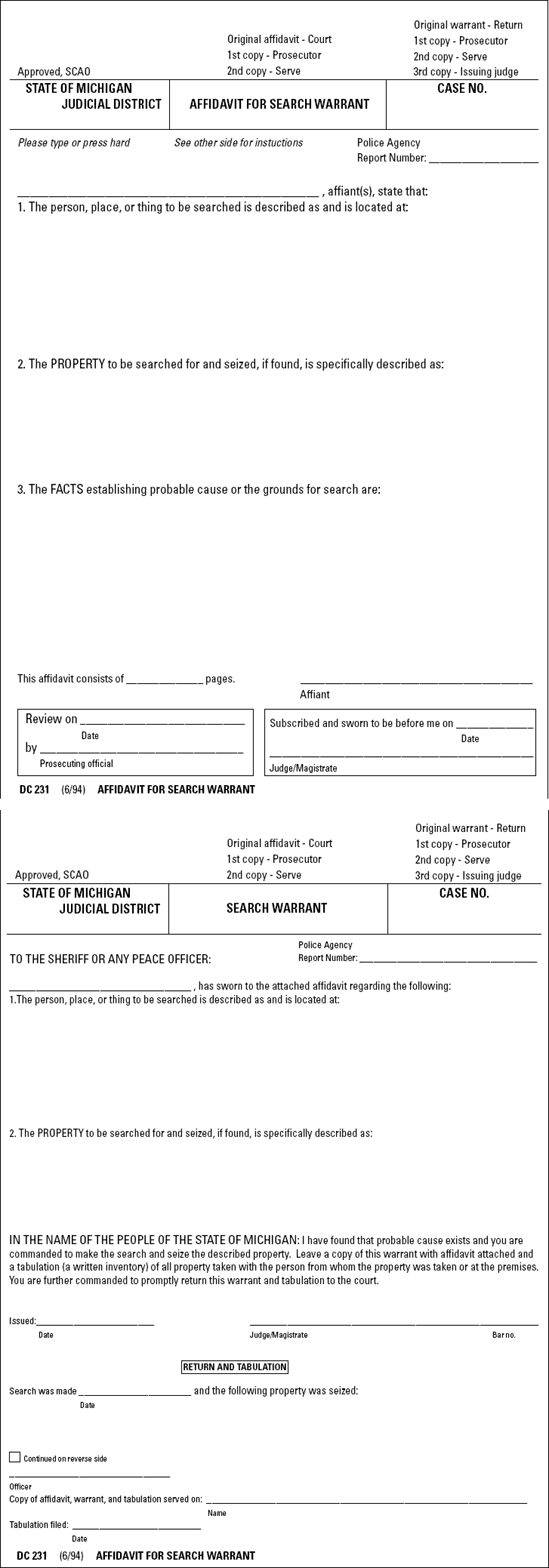

After you have in hand the information you gathered about the case, you're ready to begin drafting an affidavit to obtain a search warrant. An example of an affidavit is shown in Figure 3-1. You can find many examples of search warrants and affidavits at the Web sites of the FBI at www.fbi.gov; CNN's CourtTV at www.cnn.com/CRIME and The Smoking Gun at www.thesmokinggun.com.

An affidavit accomplishes these three objectives:

Probable cause is the reasonable belief that a crime has been committed or that evidence of a crime exists at the site being searched. You can see that reasonable belief is a gel-like concept: It's tough to nail down. Determining whether probable cause exists depends on a magistrate's common sense in looking at the total picture of the circumstances.

Tip

The more information you give the judge in an affidavit, the more comfortable the judge is in issuing you a search warrant. Without that warrant, you're done. To stay on the case, you need to consider these four basic guidelines for drafting an affidavit:

Explain all technical terms.

Put them at the beginning of your affidavit. Don't be shy — spell out the technical information.

Be clear about what you want to search.

State whether the computer or other device you want to search is itself the evidence of a crime or is merely the container holding the evidence you seek.

Explain your processes.

Be sure that the judge understands the process of creating forensic images or other means of making a forensic copy on-site and why you think this process is necessary.

Add an explanation.

Explain why you need to seize the computer and conduct an off-site search, if that's what you think is necessary.

While drafting the affidavit for the judge, you're developing the plan for your team to follow after the search warrant is issued. The plan should include the type of forensic equipment you need in order to execute the search warrant, how the evidence is to be preserved or extracted, and how you plan to move the evidence from the scene back to your lab. But life happens, and your plan may get blown to bits by some unforeseen event. Be flexible and have a backup plan ready.

Warning

We're giving you basic guidelines — not legal advice. Always check with your local legal representative to make sure that you know how local rules apply in your case.

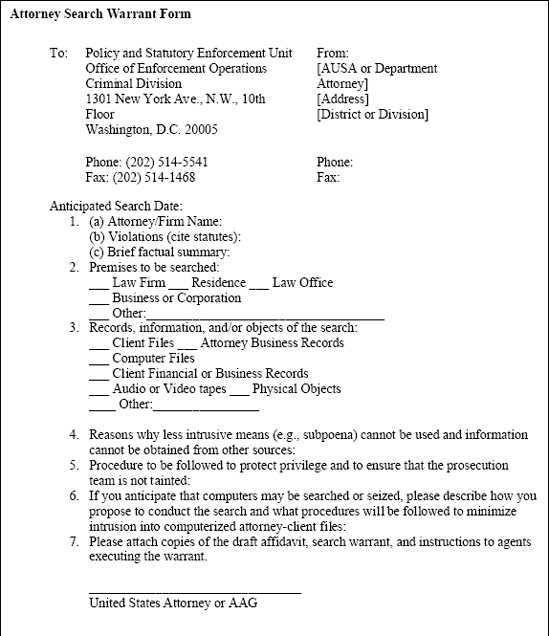

Suppose that you collected the necessary information on your case and target and you fully explained your reasoning in an affidavit. The next phase is to present your affidavit to a judge or magistrate so that she can authorize you to search and seize via a search warrant. Here are the steps in this process:

Present the judge or magistrate with the affidavit for review.

Typically, the investigative agent or prosecutor has the honor to present.

Answer the judge's questions clearly, completely, and honestly.

Judges usually have a few questions about the affidavit that you need to be prepared to answer. If you didn't learn about your case or target from the outset, this questioning session is painful. A judge may deny a search warrant if you lack the proper knowledge about a case.

Wait while the judge confirms that the affidavit is complete and the investigator isn't violating the Fourth Amendment or relevant case law.

Begging may not be effective.

Be happy if the judge issues the search warrant and move on to the next step.

If the judge declines to issue a subpoena, address the grounds for the decision, and after you satisfy the judge's concerns, resubmit the affidavit.

Review the affidavit and search warrant.

See Figure 3-2 for an example of a search warrant. See the nearby sidebar, "Keystone Cops," to understand why this step is important.

Tip

Go to

www.usdoj.gov/usao/eousa/foia_reading_room/usam/title9/crm00265.htmto print a search warrant.Execute the search warrant as soon as possible and complete your case.

Note

Take the search warrant with you to the scene with as many copies as you think you will need for everyone involved.

Searches of company or organizational computer assets under direct control of that company or organization don't require a search warrant. Whether government agents or agents of the company perform the search, it can usually be done without a warrant if a person in a position of authority of that organization authorizes it.

When you're asked to conduct a search by an organization or an asset it controls, keep these principles in mind:

Get authorization to search in writing from someone who is authorized to give it.

In large organizations, issues of overlapping responsibility can create a problem for you. The last thing you need is another manager showing up and angrily demanding that you stop what you're doing. Your response should be to present the signed authorization.

Tip

If you're not sure who can give you authority, check the organization's policies and procedures. You might find out whom to ask. Or, the person using the computer of interest can grant this authority.

Adopt a trust-but-verify mantra.

This strategy works for the military and also serves you well!

Most organizations have policies that employees must sign as a condition of their employment. Just to double-check that everyone understands why you have the authority to conduct your search, pay close attention to the part about any expectations of privacy on company-owned computer equipment. U.S. courts have generally ruled in favor of the organization as long as employees are made aware that any activities they perform on company computers aren't considered private and are, in fact, subject to company monitoring.

If no such policy exists, you generally need formal written permission as a backup to the verbal permission you received to conduct the search.

Note

Always have some form of authorization for whatever you do.

The first thing to know about verbal permission to search a computer is that it's a bad idea. But you may face an urgent circumstance where it is impossible to receive formal or written authority in a timely manner. Here are two examples of valid reasons:

Digital evidence is easily destroyed or changed by something as simple as a keystroke.

In cases where a suspect may destroy evidence, a verbal authorization is all you may have time for. Under exigent circumstances, the law provides for discretion on the part of law enforcement officials to search or seize evidence to preserve it.

Digital evidence is extremely mobile and volatile.

With the advent of e-mail or other network software, digital evidence can speed across the globe in the blink of an eye, so waiting for a search warrant in circumstances where the data may no longer exist in five minutes usually calls for verbal permission.

Warning

For non-law enforcement and law enforcement, receiving verbal permission and only verbal permission is essentially playing Russian roulette because without written authority, it's your word against theirs.

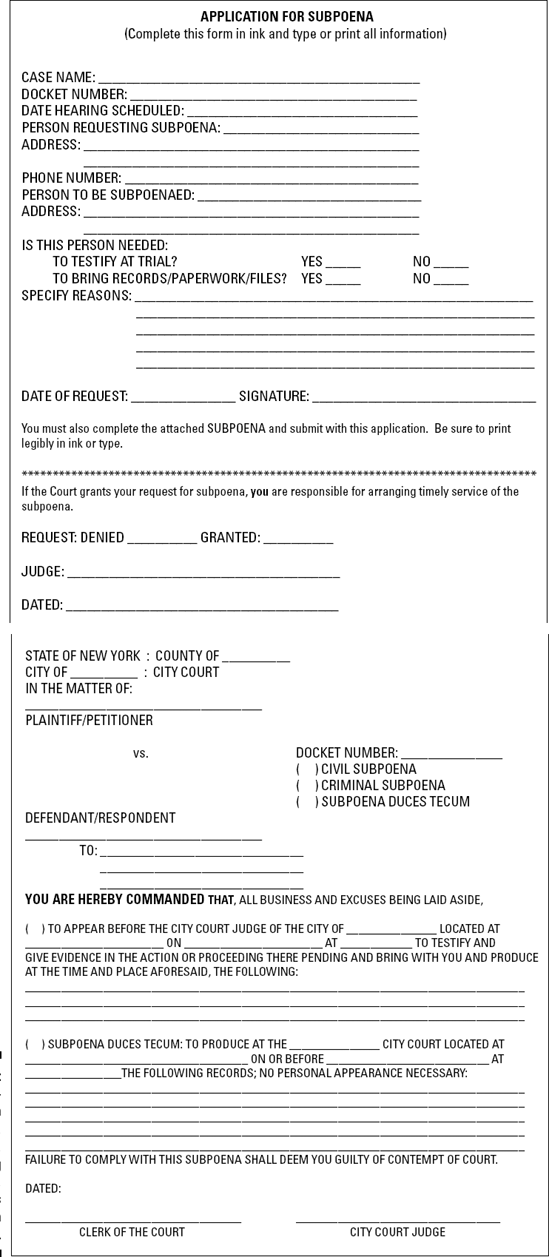

In civil cases, subpoenas are used to gain access to and collect evidence for trial. The word subpoena translates as "under punishment." Figure 3-3 shows an application for a subpoena.

In law, a subpoena is a command to do something. Two types of subpoenas of interest to you are described in this list:

Subpoena ad testificandum: This type of subpoena is the one you typically think of when you hear the word subpoena. This type of court summons compels the witness to appear in court or another specified location to give oral testimony at a hearing or trial.

Subpoena duces tecum: This Latin phrase translates to "bring with you under penalty of punishment." This type of court summons compels the witness to do three things:

Appear in court or another specified location.

Provide oral testimony for use at a hearing or trial.

Bring evidence in person and produce to the court any documents, files, books, or papers that can help clarify the matter at issue.

The clerk of the court usually issues subpoenas on behalf of the judge and, in most cases, also issues blank subpoenas to attorneys practicing in the court. This arrangement makes sense because clerks are considered officers of the court. To you as the technical expert, the attorney on your team therefore has the power to issue subpoenas commanding the other party to turn over evidence or preserve evidence or give you access to the evidence.

Tip

Just because you don't have to ask a judge for subpoenas, don't consider it a free pass to do sloppy work.