8

Power offer execution

A tape recorder that didn’t record

As we have seen, the iPod is a great power offer but, interestingly, its success is built on a competitor’s earlier power offer. It is well known that Sony originated the era of personal portable sound systems with the Walkman but missed the opportunity to do it again in digital music players. What is less well known, is the genesis of the Walkman’s huge success – it was due to a crucial course-changing decision made well after its design was completed. This innovative product was saved from premature death only by a brilliant change at the point where design hits execution.

Back in 1979, Sony was having trouble with the launch of its revolutionary new offer. The problem? The Walkman met sceptical resistance from potential users, retailers and the press alike. Its portability was appreciated but it had an important perceived defect – its inability to record. Consumers compared it with what they were familiar with – a tape recorder – and they saw what it couldn’t do, rather than what it could do.

Sony thought of a way to change that. The company distributed the Walkman to young recruits in Tokyo, New York and other large cities and told them to just stand on street corners enjoying the music. If anyone asked them what they were doing, they were to place their headphones over the enquirer’s ears. With this, the perception of the Walkman was instantly transformed from a tape recorder that couldn’t record into a portable personal sound system. The basis of comparison was no longer a tape recorder but a ‘ghetto blaster’, the huge, (barely) portable sound system so frequently seen at the time being lugged on teenagers’ shoulders. Literally, there was no comparison – the Walkman won the sound and portability battle hands down.1

The Walkman achieved tremendous momentum and contributed to making Sony an exemplary momentum-powered firm at the time. The click that changed everything was a brilliant initiative at the execution stage – one that corrected the perception of a non-compelling proposition in an otherwise technically innovative, well-designed product.

The execution of the power offer

The principal difference between design and execution relates to where the two activities are conducted. Although design must, of course, be externally focused to be successful, the process is largely internal, where the firm has control over the variables. On the other hand, execution happens in the outside world, where unexpected reactions and events can make a mockery of the best-laid plans and force rapid re-engineering of offers that once appeared to be perfect.

The initial step in execution is to ensure that the design is properly implemented as originally intended, but that’s only the first step. In order to increase the intensity of the momentum effect, momentum-powered firms continually improve their offers by learning from the experience of customer reactions. Sony rapidly realized there was something wrong with the way the Walkman was demonstrating its value, so the company quickly searched to optimize the perceived customer value inherent in its offer through a clearer and more compelling proposition.

This interactive process between the design and execution of power offers is at the core of momentum strategy. It has implications for the underlying logic of running a business – it represents a new business model.

From product focus to value focus

Traditionally, firms’ operations have been product focused. The emphasis has been develop the product, make the product, sell the product. This is the easiest way to run a business – it corresponds to the specialties of separate departments of the firm. It is the natural outcome of how companies are organized.

Customer considerations – such as market research and customer product tests – are often added on top of this product-centered approach, but they are peripheral. Even if they use the tools and jargon of customer research, these firms are instinctively inward looking. This approach critically limits the growth potential of momentum-deficient firms. However, it still dominates the business world – it is the easiest way to manage.

A second business model, based on the concept of ‘value delivery’, emerged in the late 1980s. As competition increased and customers became more demanding, more firms focused on customers and the value delivered to them. This approach clearly recognizes that customers do not purchase products for what they are, but for the value they carry.2

A value-delivery-based model has three key phases – select the value proposition, create the value and communicate the value. In the case of Swatch, we could say that the value selected was fashion. This value was created through the use of professional designers hired from outside the watch industry, and this value was effectively communicated through advertising, packaging, point-of-sale displays and public relations.

One of the direct implications of the value-delivery approach is that multifunctional teams are essential to encourage effective cooperation between departments, especially R&D, marketing and operations. This is unquestionably a vast improvement on the traditional product-based approach. Firms that adopted it improved the quality of their offers and opened new growth opportunities for themselves.

Momentum as a new business model

As a business model, momentum goes much further. Its ambition is to create extraordinary growth through customer traction. It is impossible to achieve this through a traditional linear process. The momentum approach takes the value-delivery perspective into an interactive and iterative mode in two ways. We illustrated the first, in particular with the example of Swatch, in the previous chapter. We have seen how the design of a power offer follows an iterative process – dynamic iterations are essential to achieve a compelling proposition, a compelling target and power crafting that will create the resonance necessary for a power offer.

The second need for constant interaction is between design and execution – a permanent state of flux between the two that enables each to feed off, and improve, the other. For this to happen, one must recognize that continuous improvements, both in design and execution, are possible and necessary to make the offer more compelling and more powerful. These two phases follow exactly the same process, as shown in Figure 8.1. As the Walkman example demonstrates, new insights can appear in the field and dramatically increase a product’s momentum and growth potential. These insights can either lead to ad hoc adjustments in the field or be fed back to design. Either way, they continuously improve the offer and its momentum potential.

Figure 8.1 The momentum business model

This symbiotic relationship between design and execution requires humility – it is a recognition that, even with an excellent outside-in perspective, no design can be perfect. In addition, the competition will improve its own offers and customers’ expectations will keep increasing. Power offers must be constantly and rapidly reworked in the light of new customer discoveries. A key strength of momentum strategy is the way that it encourages firms to learn from their external environment and to act swiftly on their discoveries.

The momentum business model reflects the story of great power offer successes. These were not the results of tidy, compartmentalized, linear stages but, rather, of multiple iterative interactions. Two of these interactions are particularly important. The first concerns the search for a continuous and ever more powerful resonance between the three pillars of a power offer, and the second deals with efforts to ensure an effective synergy between design and execution of the offer.

The dynamic evolution of power offers

A power offer’s dynamic evolution means that its compelling proposition, compelling target and power crafting must be adapted where needed. However, the order in which we present these three pillars should not be considered to be a prescribed sequence. Successful power offers have emerged from:

- product, distribution or communication innovations (power crafting)

- the identification of a potential valuable group of customers (compelling target)

- or from an unsatisfied need (compelling proposition).

Imposition of a dogmatic sequence would reduce opportunities for a free and aggressive entrepreneurial approach. You have to start from an insight with potential, whatever its origin, and build on it to transform it into a powerful offer. One may wish to approach the design phase with an organized process, but the need for opportunistic initiative is especially strong in the execution phase, where direct customer experience will bring new inputs in a non-controlled fashion.

In what order the process is conducted, and where each subsequent improvement of the offer starts, is totally irrelevant. What is important is to grab opportunities to improve the power inherent in an offer, to strengthen each of its three components and to ensure that they are mutually supportive, coherent and aligned.

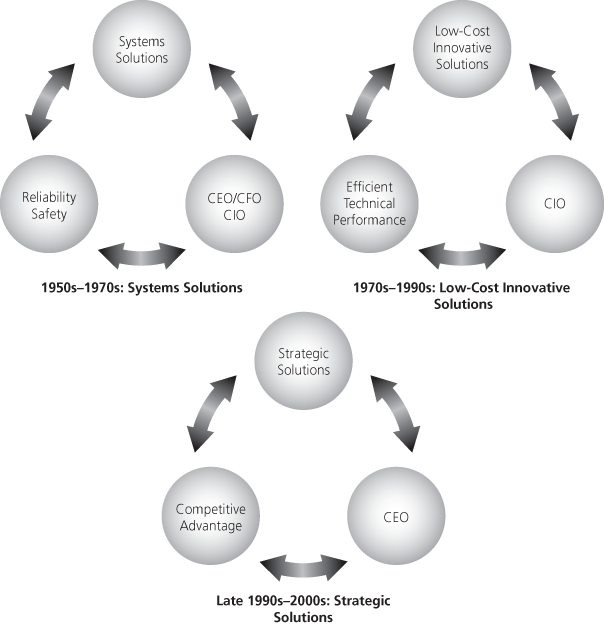

Whatever the starting point, compelling proposition, compelling target and power crafting must be continuously improved and aligned throughout the design and execution phases, and over the life of a power offer. This is true at all levels from a specific product to an entire firm. Let’s illustrate this point by taking a fresh look at an old story. How do the successes and misfortunes of IBM over 50 years of its history look when viewed from the perspective of the momentum model?3 Figure 8.2 shows a power-offer perspective covering over half a century of IT in business. It is a simplified view, and it has its limits, but it highlights the crucial value drivers in terms of compelling proposition, compelling target and power crafting.

Figure 8.2 The evolution of business IT power offers, 1955–2005

The first phase was the establishment of IT as an essential tool for managing a modern corporation.4 Business computers were brought in to replace clerical workers performing repetitive tasks such as payroll, and to do them more cheaply and reliably. Typically, suppliers would contact computer managers and make feasibility studies and proposals for investing in these impressive new machines.

Given the size of the investments and the potential impact on the business, IBM understood that the key decision makers were not the computer experts but the chief executives and heads of finance, CEOs and CFOs. It also realized that because early generations of computers were unreliable, CEOs were kept awake at night worrying that massive computer failure could threaten the entire business. IBM understood who the key decision makers were and the deep emotional costs and benefits tugging at them in relation to their computer-purchasing decisions. Unlike its competitors, IBM systematically built relationships with CEOs and CFOs to create the compelling proposition of reliability.

IBM’s whole offer was crafted to resonate with this compelling target and this compelling proposition. The company carefully built a reputation for high-quality service and rapid reaction to problems. Over the years, word got around that ‘Nobody got fired for buying IBM’. Its price was generally set 15 per cent higher than its competition.

IBM’s power crafting, from R&D to service to pricing, was coherent and in line with the compelling proposition of reliability that resonated with its compelling target. A revealing example of this resonance was the dress of its salesmen – dark blue suit, black tie and white shirt. Competitors made derisive remarks about IBM’s dark blue ‘uniforms’ but only half-understood that this dress code was the sign of a coherent, resonant strategy – and part of a power offer.

The company’s momentum strategy had created a power offer that generated tremendous momentum, and it demonstrated continuous excellence in the design and adaptation of its power offer. IBM won a dominant position with a global market share in excess of 70 per cent in mainframe computers.

However, the situation evolved and IBM’s offer became less in tune with customers’ requirements. Computer reliability increased to the point that it was no longer an issue – PCs became routine business investments. Technology progressed more rapidly, and competition developed new power offers with minicomputers and later with microcomputers. Purchasing decisions moved down the client organization. CIOs wanted low-cost innovative solutions providing higher performance.5

IBM had become so dominant that it was no longer listening to its customers – not understanding the strategic nature of the changes in its environment, adapting too slowly to a changing world. It failed to take its offer through the constantly iterative process of design and execution. Its power offer stagnated and lost its power. The company lost its momentum.

The impact was so dramatic that IBM entered a major crisis in the early 1990s that led to the appointment of Lou Gerstner as its new CEO. We will look at Gerstner’s style of leadership in some detail in Chapter 13, but what is important here is to understand how he designed and executed a new power offer, one well adapted to the industry’s new challenges. Gerstner realized that the customer world was evolving again, into one in which IT could provide businesses with strategic solutions and a competitive advantage based on new technologies like the Internet, networks, servers, databases and process application software. This was a compelling proposition of direct interest for CEOs, and it led to large-scale projects with tremendous potential in customer equity. It required stronger integration of its product lines, a major investment in new consulting services and alliances with partners. The new power offer revived IBM, gave it renewed momentum and propelled it on to a new growth course.6

It is good to see that momentum can be regained, but it does not have to be lost in the first place. Gaining and maintaining momentum is all about continuously improving the power behind the offers. And this is done by systematically reconsidering their crafting, their compelling proposition and their compelling target at the design stage and in the field.

The business value of momentum

As pointed out in an earlier chapter, the word ‘power’ in the expression ‘power offers’ has a double meaning – power with customers and power to generate growth. Obviously, the two are connected – power with customers provides the traction for the momentum that powers growth. Efficient growth is the ultimate business impact of momentum – it has the power to propel a firm into a different league.

This is not just a dramatic figure of speech. We have empirical research and computer modelling to substantiate it. We often find that even the most talented and experienced business leaders totally underestimate the astonishing returns that momentum can generate, simply because visualizing dynamics over time requires us to think in too many directions at once. If you ever need to convince a financial analyst why momentum matters, the following section, demonstrating the impact of very small changes in a few key drivers of performance, will help you make the business case.

Imagine this two-firm scenario – Momentum-Powered Inc. is a company with a strong power offer, and Momentum-Deficient Inc. is one with a perfectly decent and competitive, albeit unexceptional, offer. We have run these two firms through a computerized simulation that shows how a few momentum-based differences between the two firms will have a massive impact on future growth.

At the start of our comparison, both firms are identical in all respects other than the power offer. They both generate the same revenue and make the same profit from their current product. Both have the same number of customers, both acquire the same number of new customers through marketing activity each year and both spend the same amount on marketing in order to get them. In addition to this marketing spend, their other costs in delivering their products are the same. Furthermore, each firm is launching a new product. The firms are selling their new products at the same price and are making the same margin and the same marketing investment.

Excellent execution accelerates momentum in a number of ways that we will review in the following chapters, but in this simulation let’s consider just four – sales growth, cost efficiency, cross-selling and customer recommendations. We will assume that Momentum-Powered Inc. derives advantages from each of these four drivers. However, in order to demonstrate the power of these drivers’ ability to deliver momentum, for the sake of this simulation we shall assume very small improvements and investigate the impact on total growth.

Because Momentum-Powered Inc. has a greater understanding of its customers’ needs, its offer is more powerful. As a result its customers will buy more. In most cases, this impact can be significant but, for argument’s sake, let’s assume that its better offer adds just 1 per cent a year to its revenue growth. Consider how many more iPods and Wiis are sold than alternative products and you’ll agree that we are allowing Momentum-Powered Inc. a very modest advantage.

In addition, its deeper understanding of what customers truly value and what they don’t enables it to shave something off its costs. In the previous two chapters, we saw how the process of optimizing compelling customer value and compelling customer equity reveals areas in which costs can be eliminated. Remember that some of the power offers we examined, such as Dell and First Direct, ‘shaved’ 40 per cent off the traditional cost base for their sector, but again, let’s assume that this process skims just 1 per cent a year from the costs of delivering value to the customer.

With the new product, we see the effect of the third way that momentum can impact results – cross-selling. The fact that Momentum-Powered Inc. enjoys greater customer engagement than Momentum-Deficient Inc. means that the two firms will have differing fortunes when it comes to convincing their existing customers to adopt their new product. Momentum-Powered Inc.’s customers trust it to deliver exceptional value, and its greater customer focus means that it is better at creating powerful offerings that will be enthusiastically adopted. Momentum-Deficient Inc.’s customers, on the other hand, while probably not dissatisfied are not particularly engaged with it. They do not believe that its new product will be anything exceptional and may even view it with deep suspicion.

As a result, for the sake of this example, we have assumed that each year 5 per cent of Momentum-Powered Inc.’s existing customers, just 1 in 20, will adopt its new offering. Because of their lower levels of trust and engagement, just 1 per cent of Momentum-Deficient Inc.’s customers will do so with its new product.

Finally, let us consider a fourth accelerator of momentum – customer recommendations. Power offers tend to be so good that existing customers recommend them to friends. As a result, momentum-powered firms acquire a number of new customers every year solely through the free tool of recommendations. For instance, almost all of Skype’s customers came through recommendation and many other Internet firms have also based their growth on such a model.

Our research has established that momentum-powered firms in more traditional industries can attract between a third and two-thirds of their new customers through word of mouth. At its peak, First Direct’s acquisition from word-of-mouth recommendation every year equated to 15 per cent of its existing customers convincing a friend to join. We’ll continue to play down our estimates and say that each year 5 per cent of Momentum-Powered Inc.’s customers recommend it strongly enough to persuade a friend to buy. While some of Momentum-Deficient Inc.’s customers may recommend it, they rarely do so with much vigour. Consequently, a statistically insignificant number of people come to Momentum-Deficient Inc. via recommendation.

With these relatively modest differences in momentum drivers, how different will the destiny of these two firms be? Well, within five years these two formerly comparable businesses have begun to operate in totally different leagues. Momentum-Deficient Inc. is performing well, but as Momentum-Powered Inc.’s performance accelerates it leaves Momentum-Deficient Inc in its wake. At the end of just five years, its profits are increasing more than twice as fast as Momentum-Deficient Inc. and it is generating 50 per cent more profit than its former equal.7 Managers usually wildly underestimate the impact of small improvements on key momentum drivers.

As we shall see in following chapters, these are only some of the momentum accelerators that firms can harness to drive performance – and our scenario allowed for only partial, modest improvements. Consider the possibilities if they were all harnessed and delivered their full potential! As the chain reaction of momentum takes hold and power offers help the business to build more and more impetus, momentum-powered firms sail along on efficient long-term growth. Their potential for growth appears to be unlimited.

The ability of momentum-powered firms to deliver higher revenue and to simultaneously reduce or redirect costs powers their performance. Think back to the Pushers and Pioneers we looked at in the first chapter. Powered by their momentum, the Pioneers achieved almost double the revenue growth of the Pushers over 20 years. By achieving more for less, they deliver greater value to their customers and their stockholders. In the process these firms become better and more rewarding places to work and are more admired and respected by their other stakeholders. The momentum continues. The firm’s performance improves further. On it goes.

The chain reaction of the power offer

The virtuous circle of momentum

The execution of a power offer is the beginning of a chain reaction that builds momentum and drives profitable growth – vibrant execution. At each link in the chain, the results get more powerful – each one provides further acceleration. And, as with the compelling design of a power offer, what sets momentum-powered firms apart is the scale of their ambition. They want their power offer to provide a deeply fulfilling customer experience. They are aiming for intense responses – responses at an emotional level, responses that are vibrant and alive.

This vibrancy and ambition runs through the whole second engine of momentum strategy – not just good customer satisfaction but vibrant satisfaction, not just better than average customer retention but vibrant retention, not just a level of customer engagement but vibrant engagement. As we can see from Figure 8.3, each of these four drivers of momentum accelerates the chain reaction of vibrant execution and increases the intensity of the momentum effect.

Figure 8.3 How momentum execution accelerates growth

The higher the level of customer satisfaction then the greater the vibrancy about it and, the more emotionally positive customers will become. The more positive the emotions then, the more customers will be inclined to develop their relationship with a firm. Customer retention translates that emotional state into the action of continued, repeat business – if the retention is vibrant enough. The more vibrant their retention then, the more likely they are to become engaged. The more vibrant their engagement then, the more compelling their equity will become and the more compelling value they will reveal to a firm, enabling it to improve its offer further and create yet more vibrant levels of satisfaction.

It is an ambitious virtuous circle in constant motion, attracting customers, retaining them and building their equity. Remember the Chapter 3 example of Skype? The vibrant levels of engagement it built up were the direct result of its customers’ vibrant satisfaction and the fact that these customers have vibrant reasons for being retained. The level of engagement is evidenced by the way that Skype’s customers care about the firm – fans regularly contact Skype to offer advice on how the company can improve its offer. It is almost self-perpetuating. Successful power offers lead to vibrant satisfaction, which leads to vibrant retention, which leads to vibrant engagement, which in turn leads to even more powerful offers, which then further enhance customer satisfaction and so on. This is real momentum.

Once a power offer has created traction, the resources required to maintain momentum are minimal. This is because it is largely driven by the acceleration that each stage of the virtuous circle provides, as the illustration of Momentum-Powered Inc. and Momentum-Deficient Inc. showed. The resources to create momentum in the first place have been invested upstream, in the exploration of customer value and customer equity that lead to the design of a power offer. This is a far more efficient way to generate growth than the dominant business practice of developing an offer with an internal focus and investing resources downstream to convince customers of its value. The momentum business model requires that financial and managerial resources be shifted upstream in order to generate higher growth more efficiently.

Once momentum has been created through customer traction, it needs to be maintained and accelerated. This can be achieved in two phases. First, by ironing out any problems in the execution of the offer at each of three stages – customer satisfaction, customer retention and customer engagement – by discovering sources of friction and mobilizing the entire organization to eradicate them. Secondly, by constantly learning from customers and feeding the resultant new insights and opportunities back into improvement of the power offer design.

Breaking the vicious circles

In contrast, momentum-deficient firms can be trapped in the vicious circle of peddling weak offers. They generate average satisfaction, which leads to customer defection or the passive retention of not very happy customers. This will generate either negative customer engagement or, at best, an absence of engagement. Either way, the offer will be weakened even further.

A vicious circle makes the generation of growth an uphill struggle for momentum-deficient firms. Momentum-deficient leaders are often preoccupied with managing internal forces because there’s no momentum to power them along. Frequently, staff within large companies are tired and demotivated – their work is a struggle.

Generating growth in a company without momentum is a tall order. Employees need to be motivated so firms invest resources to improve their effectiveness, customers are dissatisfied so money and resources go out to solve that problem, customer retention is difficult so firms try solutions such as expensive loyalty programmes, a lack of customer involvement requires higher investments in advertising.

These dreary scenarios show the vicious circle at work. Lack of customer focus forces organizations to compensate by ploughing more resources into fuelling growth. This is what we have called compensating strategy, and it is the exact opposite of momentum strategy. Admittedly, as the Pushers in our study demonstrate, it can work but companies end up with customer churn. The vicious cycle persists, underlying profitability drops and costs must be cut in order to compensate.

In such situations, paradoxically, many businesses still appear successful in terms of industry benchmarks. This is because benchmarks compare like with like. They look at ‘what is’ rather than the unlimited potential of ‘what could be’. Benchmarks in this sense are tools for maintaining mediocrity.

These vicious circles are very damaging for a firm, compensating for weak offers with expensive marketing and sales investments. These resources are often subsidized by other products that are weakened as a result. And they limit the investments that should be made upstream in developing improved offers.

In the end, these vicious circles are unsustainable. Business is likely to collapse when customers become more knowledgeable or when the competition turns out a better offer. It is essential to identify vicious circles and to break them before they break a business. This can be handled by gradually shifting resources upstream, away from inefficient compensating strategies and toward development of better offers. They must originate new value. To escape the vicious circle one must craft power offers that will create customer traction and build a new momentum for efficient growth.

Building and sustaining momentum

Once the power offer has been designed and set into action, the focus shifts. What counts now is the way that the chain reaction that produces momentum is built and nurtured. This process will be the subject of the next three chapters. There are two fundamental themes that will recur at each of the three stages of customer satisfaction, retention and engagement – understanding the emotions that drive momentum and executing a systematic action programme to sustain momentum.

Understand the emotional drivers of momentum

Emotions powerfully affect every stage of the momentum chain reaction. Understanding them is as crucial when executing a power offer as it was in designing it. Certainly every customer is different, but there are a few psychological drivers of emotions that are universal. One of the most pertinent is dissatisfaction – customers never settle for the status quo.

Consider the market for anti-ulcer drugs. It has gone through multiple momentum cycles despite the fact that the ‘nearly perfect’ drug was launched more than 30 years ago. Before SmithKline introduced Tagamet in 1976, the only treatment available for stomach ulcers had been highly unsatisfactory – painful, risky surgery. Tagamet’s six-week remedy was an irresistible power offer. It cured most ulcers with practically no side effects, quickly achieved annual revenues of nearly $1 billion and created enormous momentum for SmithKline. Then the firm got complacent. Reckoning that the anti-ulcer problem was solved, SmithKline stopped its research efforts in this field.

Bad decision. In 1981, Glaxo introduced Zantac, a product that offered only marginal improvements on Tagamet – but it was new, and it supplanted Tagamet as the power offer for ulcer treatment, reaching more than $3 billion in annual revenues. Glaxo gained tremendous momentum and became a leading global pharmaceutical firm. Could there be a greater success than this? Absolutely. In 1989 AstraZeneca launched Prilosec, a drug with a new mechanism of action. This drug achieved annual revenues in excess of $6 billion, created exceptional momentum and led AstraZeneca to global status.8 Wisely, the company improved on its own offer with a new drug, Nexium. This is currently the top brand on the market.

What is the root of all this? Human nature – doctors and patients crave better solutions. Dissatisfaction drives the market and companies will always develop more sophisticated and effective remedies. Tagamet’s huge advance disappeared when more powerful offers became available. The same cycle has repeated itself four times in 30 years. It never stops. That’s the human story.

And this fundamental human desire for progress cuts through every market. Human nature is the driving force behind momentum. This simple fact allows business enormous and endless growth potential.

Implement a systematic action roadmap to momentum

Be ambitious! Standard benchmark targets are not enough for surviving and thriving in business today. It is important that all the conditions that give rise to the momentum effect are in place and aligned – but it is even more important that they are intense. You must aim over the horizon for the ultimate goal of momentum – positive, active, vibrant involvement of customers with the firm and its offers.

Firms must understand their customer portfolio in terms of the forces that influence momentum and growth. For each stage of the execution process, they must have a feeling for what proportion of their customers loves them, repeatedly buys their products and promotes them to their friends – but also what proportion has been disappointed, hates the firm and actively denigrates it.

Building and sustaining momentum requires an approach to systematically nurture the forces that improve it, and to systematically decrease or eliminate the forces that hinder it. We have developed such an approach and we will frequently refer to it in succeeding chapters with the acronym MDC. As shown in Figure 8.4, it stands for mobilize stakeholders, detect sources of frictions and insights and convert customers.

Figure 8.4 The MDC action roadmap to momentum

- Mobilize first, because momentum requires organizations to unify and motivate their stakeholders towards the single-minded pursuit of vibrant levels of customer satisfaction, retention and engagement. Employees in particular are the interface between a firm and its customers. If they are not motivated to deliver a momentum-building experience for customers then all your other efforts are doomed to failure.

- Detect second, because insights and sources of friction at all levels are the potential boosters and deterrents of momentum. Any factor that can slow down momentum in any way should be identified and removed. Similarly, new insights to increase customer value or customer equity should be spotted and acted upon.

- Convert third, because momentum ultimately depends on increasing the number of customers with vibrant emotions for the firm and its products. Removing friction and acting on insights will create a strong positive engagement and accelerate momentum. Critical customer feedback is always an opportunity for improvement. Ill-disposed customers and ex-customers can damage momentum, so it is imperative to take action to reverse their negative emotions. Equally important is to continuously search for ways to make existing customers even more satisfied, more loyal and more engaged. And finally, new insights should always be exploited to help convert non-customers and bring them into the company’s fold.

The MDC roadmap will help firms to mount a systematic search for momentum killers and boosters in all three areas – mobilization of people, detection of insights and sources of friction, and conversion of customers. The roadmap, along with the insights that we will develop over the next three chapters, will deepen and sharpen your perspective on momentum. The outcome should guide your actions to foster profitable growth. The momentum execution matrix in Figure 8.5 is a valuable tool to display the key momentum killers and boosters that require your total attention at each of the four stages in the virtuous circle of momentum execution. It is your strategic agenda for momentum execution towards exceptional growth.

Figure 8.5 The momentum execution matrix

Turn traction into momentum

A power offer creates traction. Execution of the offer uses that traction to generate momentum. But execution does not cease once momentum has been established – far from it. The initial momentum must be maintained and enhanced through a process of continuous adjustment and improvement.

We have established five guiding principles for effectively executing power offers.

- The momentum business model builds and aligns the three pillars of a power offer – a compelling proposition, a compelling target and power crafting – so that they resonate and create customer traction. This iterative process extends from design to execution and back again. Design and execution are much more powerful if they are symbiotic.

- Continuous adaptations and improvements must be explored during the execution of a power offer and fed back into its design. Focusing on a power offer’s three pillars helps in detecting tactical opportunities for improvement.

- Relatively small changes in momentum drivers such as retention, cross-selling and customer recommendations can have a substantial and sustainable impact on a firm’s future competitive position.

- The accelerating effects of four related components – power offer, vibrant levels of customer satisfaction, retention and engagement – lend a potent thrust to momentum. These four components support each other in a virtuous circle.

- Building and maintaining momentum requires a clear understanding of the emotional drivers of behaviour and a systematic roadmap for action that we call MDC – for mobilize, detect and convert.

One of the telling characteristics of a well-executed power offer is its efficiency. Power offers prove that less is more – momentum-powered firms achieve more while spending less in the execution phase. They do not have to compensate for a lesser offer with expensive tactics aimed at luring customers. Instead they benefit from the tremendous power of customer traction. To follow in their footsteps, we must shift resources from downstream to upstream activities – engineer an offer with customer traction built in instead of trying to convince customers of its worth when it has to be sold.

Once momentum has been established, a firm must continuously seek to maintain and accelerate it. This is the subject of the following chapters. They will show how a systematic approach can help firms to develop and maintain the momentum that will make them join the Momentum League – and enjoy exceptional growth.