9

Vibrant satisfaction

Moments of truth

The most important moments in the relationship between a company and its customers are the intersections, the points where they encounter each other. This is when value is delivered – the moments of truth,1 as Jan Carlzon, the former head of Scandinavian Airlines, termed them. It is irrelevant who instigates them or where, when, why or how these encounters happen – every single one of these moments matters.

For his company, Carlzon said, they represented 50 million battles that he could win or lose. At the other end of the scale, A.G. Lafley, chief executive of Procter & Gamble, wants his whole organization to focus on two crucial encounters:

There are two moments of truth that we compete for. First, whenever the customer shops, we stand for election, and either we get her vote or somebody else does. The second moment of truth is when she, or a member of her family, uses our products and they are either satisfied or they are not. Being aware of this has proved incredibly focusing.2

The accumulation of moments of truth shapes a customer’s experiences of a product or service and crafts his or her perceptions of the value received from the firm. If the firm wins, these moments feed customer satisfaction, which in turn fuels customer traction and momentum.

It is up to leaders to frame the concept of moments of truth as they like, whether in Carlzon’s millions or by Lafley’s focus of merely two. However framed, these moments of truth directly impact customer satisfaction.

If the design and execution of the power offer are successful, the moments of truth will provide superior customer experiences. They will create vibrant customer satisfaction and offer the first evidence of the customer traction inherent in the power offer.

Why vibrant?

Many companies have a significant number of customers whose relationship with the firm never develops beyond the transactional – there is no emotional connection. To generate the momentum effect requires a much deeper and more committed relationship than that offered by passive customers who just don’t complain. Companies should measure their success by the proportion of delighted customers they have – people so thrilled with a product or service that they can’t help but tell others about it.3

Aiming to satisfy customers is not enough. That is an average, complacent and mediocre goal. Momentum-powered firms are more ambitious in their customer satisfaction objectives. Their target is truly intense, can’t imagine any better satisfaction – vibrant satisfaction.

The basics of customer satisfaction are laid early on. It’s not based merely on interactions between the customer and the firm. The perception of a product or service hatches during the design and execution of an offer. It is shaped by marketing activities such as pricing, communication, selling, distribution and other forms of promotion, often before the customer even sees the product.

Targeted customers’ perceptions appear in two stages. First, customers make judgements on the initial communications of a product or service that will encourage them to try the offer for the first time. Secondly, customer satisfaction evolves based on their initial experience.

Vibrant customer satisfaction is essential because it is the first sign that a firm is acquiring customer traction. If a firm has high customer satisfaction, it is likely that customer momentum has already begun – steps can be taken to accelerate that momentum. Conversely, if customer satisfaction is low to non-existent then, momentum will never get going unless the causes of low customer satisfaction are addressed.

Adopting the term ‘vibrant customer satisfaction’ indicates that a firm is committed to building intense customer feelings and emotions from its power offers, right through every moment of truth. The use of words like ‘intense’, ‘feelings’ and ‘emotions’ is deliberate. They evoke the aspects of human nature that have the strongest impact on customer satisfaction.

The emotions beneath satisfaction

Satisfaction is a state of mind. This fundamental fact is totally overlooked when management refers to customer satisfaction in percentages tracked like accounting numbers. The danger in such simple and seemingly objective representations of satisfaction is that they will be mistaken for reality, in place of the subjective but more complete and intense reality – the ‘real’ reality of the customer experience that they are trying to measure.

To ensure that customer satisfaction boosts customer momentum, it is important to keep in mind what it really means. Recall the exploration of how customers perceive the value of an offer – it is often deeply held emotions that drive judgement of the value of a product or service. These same emotions also drive customer satisfaction and lead to the acceleration of customer momentum.

‘Dissatisfaction inside’

Customer satisfaction is transitory. Like other states of mind, it will ebb and flow depending on the latest experience with a firm – the moment of truth. Obviously, consumers’ perceptions of a product are based on their experience of it, but increasingly they are also influenced by other, seemingly unrelated, experiences. Superior service from an online bookstore or a food retailer will decrease customers’ satisfaction with the comparatively poorer service of banks and airlines.

Human beings, as we all know, are difficult to satisfy. On the strength of this observation, Abraham Maslow constructed his theory of the hierarchy of needs, a principle well known to marketers.4 It describes how humans move up the ladder of different needs – when one need is satisfied, they aim for more sophisticated ones. Maslow portrayed a hierarchy of needs, progressing from basic to more advanced – physiological, safety, love, belonging, self-esteem and self-actualization. His thesis suggests that human beings are never satisfied because as one desire is satisfied another emerges higher up in the hierarchy.

Contemporary research on happiness as a measurement of progress uncovers the same phenomenon. The economist Richard Layard has established that as societies become richer they do not become happier.5 He shows that, on average, people have grown no happier over the past 50 years, even though average incomes have more than doubled in real terms.

Internal dissatisfaction is the engine of civilization. Without it we would still be living in caves and hunting for food, rather than aspiring to own two homes and shopping for delicacies in upmarket food shops. This explains why human dissatisfaction is at the heart of value origination, and why it is one of the underlying drivers of profitable growth for momentum-powered firms.

What are the business consequences of dissatisfaction? There are two simple implications. First, that it offers unlimited potential for growth – secondly, that a company must continuously strive to improve its offers. The relentless rise of customers’ expectations is not a result of capitalism, globalization, technology or any other such fashionable argument – it is the consequence of the human being’s dissatisfaction with the status quo.

The example of the anti-ulcer drug market we considered in the previous chapter is a case in point. When Tagamet was said to have put stomach surgeons out of business, it led to dangerous complacency for its creator. SmithKline presumed that Tagamet was the ultimate treatment for this condition and made the fateful decision to stop its anti-ulcer research programme. The company had created momentum but suffered from hubris. It failed to maintain and accelerate that momentum and reap its full benefits.

The great driver of Tagamet’s instant success – and of the anti-ulcer drugs that supplanted it – was the intensity of the satisfaction they gave. In customer satisfaction, it is intensity that matters more than anything else.

Why intensity matters

There is a very sound reason why firms that provide their customers with vibrant satisfaction do better than those offering normal levels of satisfaction. Like most momentum principles, it is grounded in the emotions of customer psychology.

Customer satisfaction is a state of mind, not an action. Its real value lies in the actions it inspires – purchases, loyalty or word-of-mouth recommendations. Actions that are driven by emotions are much more powerful than those motivated by reason. This is why it is important to relate different levels of customer satisfaction to three different states of mind – cognitive, affective and emotional. Let’s now investigate this relationship.

When most customers interact with a product or service – whether they are ‘just browsing’, actively contemplating purchasing it or already using it – they will think about it. Possibly not in a particularly active manner, true, but at some level their brain will be engaged in reflecting on their experiences as customers. Psychologists call this thinking ‘cognitive’ because it is normally founded on fact and experience and is reasoned and logical.

The depth of these cognitive processes varies widely. As customers, we think deeply about the purchase of high-cost items, such as a TV, a car or a house. In the business world, some important purchasing decisions can require task forces working for months and writing detailed reports. On the other hand, we are much less involved when buying low-cost or impulse items.

Sometimes, however, customers go beyond the cognitive stage and enter what is called the ‘affective’ level. This occurs because they either like or dislike something, and develop positive or negative feelings. At this point, they become more involved. Many people struggle to recognize their feelings as readily as they acknowledge their thoughts, but they are inescapably present, affecting our decisions. How many customers have agonized while comparing different car models before making a decision based on a feeling, a first impression, a detail or a colour? In most cases, though, a decision based on feelings is a good decision because ultimately customers live in a world governed by their feelings rather than their logic.

Sometimes these affective processes become so overwhelmingly strong that customers enter what is called the ‘emotional’ stage, in which they become excited or angry. The more intense a customer’s state of mind, the stronger the emotions – and the more likely it is that he or she will act.

A customer’s state of mind is naturally influenced by satisfaction. A neutral level of satisfaction creates no significant mental reaction. It takes a higher level of satisfaction or dissatisfaction to create feelings and affective responses – if the satisfaction or dissatisfaction becomes more extreme then emotional reactions can be expected.

It is only when customers start to be truly satisfied that they begin to develop positive feelings, and only when they become very satisfied that they get emotional. This is why it is essential for businesses to set ambitious goals and strive toward vibrant customer satisfaction, rather than just tolerating the mediocrity of mere satisfaction.

Champions and Desperados

But affections and emotions are still states of mind, even if stronger than average satisfaction. The link between customer satisfaction and momentum happens when a customer’s state of mind is translated into levels of engagement, as shown in Figure 9.1.6

Figure 9.1 Customer satisfaction and behaviour

Most of the time, customers are merely satisfied. They are passive, not engaged. But if satisfaction is very high, customers will have positive emotions toward an offer. They will be loyal to the company, quick to adopt its new products and to recommend them to others. They are positively engaged – they are the firm’s Champions.

Strongly dissatisfied customers lie at the other end of the scale. Customer dissatisfaction creates negative feelings, and extreme levels of dissatisfaction create powerful negative emotions. This can lead to harmful customer actions against the firm that apply a brake to momentum. If dissatisfaction becomes so high that it creates negative emotions, these disgruntled customers will endeavour to discourage other customers, causing damage to a company’s reputation. They are negatively engaged – they are the firm’s Desperados.

Customer momentum will be influenced at the two extremes of the satisfaction scale. It will be impaired by customer dissatisfaction and by Desperados sniping at the firm. Consequently, any source of dissatisfaction needs to be hunted down and eradicated, as we’ll show later in this chapter. Customer momentum requires positive engagement, and hence vibrant customer satisfaction. This is why it is essential to be ambitious about customer satisfaction and to monitor progress toward these ambitious goals with appropriate metrics.

Satisfaction metrics

Many firms use no customer satisfaction metrics. As a general rule, these firms lie at either end of the customer satisfaction spectrum. The best firms have an intuitive grasp of it – it is part of their DNA. They are commonly small businesses led by an inspirational entrepreneur who is deeply focused on customers.

The other firms – the majority – do not even measure customer satisfaction because they believe it is not a priority. Disconnected from their customers, they cocoon themselves in a misplaced confidence based on their own selection of anecdotal, positively biased evidence. These firms do not experience customer momentum – they are momentum-deficient.

Customer satisfaction metrics should not be a matter of choice for large companies. The gaping distance between big business and its customers means that formal measurement is a necessity. Financial analysts expect to have access to reports covering all the factors that influence the value of a firm’s physical assets, right down to office furniture and stationery. Why shouldn’t they also expect to know the factors that are affecting the value of an asset as fundamental as customers?

While there is no universal measure for customer satisfaction, there are a number of accepted standards. Often companies will proudly announce that they have a 66 per cent customer satisfaction rating, or 82 per cent or whatever – but what precisely does this mean?

The most common method of measuring customer satisfaction is through surveys. Companies ask their customers to complete a questionnaire, typically noting their satisfaction on a five-point scale that moves from very dissatisfied to very satisfied, with satisfied, dissatisfied and no opinion in between. The standard customer satisfaction ratings are reported as a percentage, combining the customers who say they are ‘satisfied’ and those who respond ‘very satisfied’.7

As a result, a customer rating of 70 per cent could mean a variety of different responses – from 70 per cent satisfied and none very satisfied, to 70 per cent very satisfied or any point in between. This is misleading in a serious way. There is a crucial difference between ‘satisfied’ and ‘very satisfied’ in terms of future customer behaviour.

This kind of basic reporting provides overly generous ratings. At best, it can guide companies badly in need of catching up but it is a totally inadequate measurement of customer satisfaction to help guide vibrant execution. A firm that aspires to join the Momentum League needs to aim much higher and use more demanding metrics.

The difficulty is that satisfaction is a state of mind, an attitude of customers toward the company, something not easy to capture on a questionnaire with just five boxes to choose from. Customer satisfaction surveys use very simple measurement tools that don’t take into account customers’ deep affective and emotional states. Notwithstanding this limitation, the link we saw between very high levels of satisfaction and emotional engagement can help to go some way to extracting a meaningful benchmark from these metrics.

‘Top box’ ambition

A high score based on the standard measurements of customer satisfaction creates an inflated and inaccurate view of the real level of customer engagement. An 80 per cent ‘satisfaction’ rating sounds very high, but it means that 20 per cent of people who paid for a product or service were not satisfied, even at the most basic level! That is an unacceptably high proportion. In addition, that 80 per cent could be composed of customers who all responded ‘satisfied’ rather than ‘very satisfied’. Customers who are just ‘satisfied’ are passive customers and provide little traction for momentum. Momentum doesn’t come from, ‘Yeah, it was OK, I guess.’

Customer delight should be the only outcome that makes management jump with glee and trumpet the news about their satisfied customers. It’s also what customers deserve when they pay for a product. One good way to make certain that a firm has become ambitious about customer satisfaction would be to report, at least internally, only scores for very high levels of satisfaction. Companies need higher expectations. Above average is not good enough – they have to focus on the ‘top box’, because this is essential to drive customer action.

The term ‘top box’ was coined by Andy Taylor, chairman and CEO of Enterprise Rent-A-Car, an American business founded in 1957 by his father, Jack, on the premise that the company would always provide a level of service that would stick in customers’ minds. As the family firm grew into an international business with 500 000 rental cars, cracks began to appear in the foundation of its success.8

In the mid-1990s, Taylor began getting an uneasy sense that Enterprise’s customer service was not as good as it should be. A number of letters, calls and anecdotes trickling through to him implied that the company was putting too much emphasis on financial metrics and not enough on pleasing its customers. Taylor decided to adopt a simple and meaningful measurement system that would give the overall metrics of customer satisfaction and also indicate whether customers would rent from Enterprise again.

Enterprise’s new measurement system tracked only completely satisfied customers – the top box. The new ratings were obviously much lower than the previous ones, which had included the ‘somewhat satisfied’ category. To counter any resulting employee demotivation, Taylor insisted that the whole point of measuring satisfaction was not to come up with figures that make the firm look as if it was doing a great job. It was to guide its efforts to be even better – to make the firm perform more effectively for its customers.

Taylor and his father then made it clear to managers and employees that the highest corporate priority was its customers – more important than growth and more important than profits. Top-box customer satisfaction scores were integrated into monthly operating reports, and no one was promoted without a customer score equal to the corporate average or higher.

Insights from the regular customer satisfaction survey were ploughed back into the business and its top-box score has climbed steadily ever since. As a result, Enterprise has been winning more repeat business, benefiting from more referrals and growing much faster than the industry as a whole.

‘Top box’ shows the importance of being ambitious about customer satisfaction. Determined to recapture its reputation for customer service, Enterprise realized that a robust benchmark was the only way to overhaul its corporate culture. The impact? Enterprise is now a $9.5 billion business and has enjoyed annual compound growth of 20 per cent over the past 25 years.

‘Top box’ is just another way of saying ‘vibrant customer satisfaction’. You choose the expression that’s most relevant to your firm. While ‘top box’ centres on clear measurement, ‘vibrant’ focuses on the desired impact. Whichever is chosen, what counts is that a firm sets its ambition much higher than average customer satisfaction, because it must engage customers at an emotional level if it is to generate positive, momentum-building action.

The impact of vibrant satisfaction

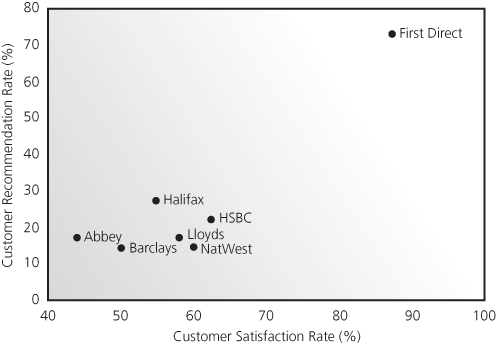

Vibrant customer satisfaction is not just for the good of customers. It makes business sense because it is a very efficient way to drive momentum growth through customer traction. This is vividly illustrated with the example of First Direct, the world’s most recommended bank, as outlined in Chapter 7.

The impact of the vibrant satisfaction experienced by First Direct’s customers is easy to see in Figure 9.2.9 To begin with, at over 85 per cent, First Direct’s customer satisfaction ratings were 25 to 40 points higher than established UK banks. Secondly, more than 70 per cent of the bank’s customers have recommended the service to at least one other person. As First Direct has over 1 million customers, this translates to a very impressive sales force of more than 700 000 satisfied customers – the very ones who brought in a third of the bank’s new customers by recommendation, at zero acquisition cost.

Figure 9.2 Customer satisfaction and behaviour at First Direct

Aiming for vibrant satisfaction

But how can other firms reach the dizzy heights of First Direct’s success? We’ve already explained how the most effective way of creating vibrant satisfaction is through designing and executing a power offer. Secondly, firms should take a number of actions aiming specifically at customer satisfaction. In our experience, these actions must first correspond to adequate objectives that stretch the firm’s ambition without discouraging employees. In a firm’s journey toward momentum, we have distinguished three different stages for customer satisfaction objectives. But all three of them – indeed, the central thrust of this entire book – share a single holy grail – progressing toward vibrant customer satisfaction.

It’s not easy to get there. In fact, companies that start the trek from a position of weakness, such as the ‘morass’ that Lou Gerstner colourfully described on arriving at IBM, might have to manage their way up toward the goal step by step through these changes. This would be preferable to attempting an overly ambitious ‘great leap forward’ and risk failure and the demoralization that would bring.

The first stage is about reaching industry benchmarks. While benchmarks generally betray mediocrity of customer satisfaction, they can also play a vital role for firms that need to catch up. For companies struggling with low levels of customer satisfaction, shining examples like First Direct and Enterprise may seem unrealistic and unattainable, so a pertinent short-term objective can be simply to increase satisfaction levels to industry standards. We view this approach as ‘minding the store’ – it is a useful exercise for firms until a more powerful offer is designed and executed.

Secondly, firms can strive to move from good to top-box satisfaction. This ensures that they don’t become complacent about adequate customer satisfaction scores. If customer satisfaction objectives are set at higher levels, this will stretch a firm and force it to remain externally focused. Enterprise’s top-box initiative is a good example of a more ambitious objective.

Finally, successful firms need to actively nurture the vibrant customer satisfaction they have gained. All the examples of momentum-powered companies we have offered so far – First Direct, Enterprise, Dell, Virgin, Skype, Wal-Mart, Microsoft – have, at one time at least, created the vibrant customer satisfaction that generated the momentum that powered their phenomenal, profitable growth. But it becomes harder when they grow bigger, more complex and more powerful.

Wal-Mart, for example, is now struggling with pockets of deeply dissatisfied stakeholders, from employees and trade unions to local communities and campaign groups. These are the retailer’s Desperados. Wal-Mart needs to manage the situation carefully in order to maintain the vibrant satisfaction that other stakeholders feel for its services.10

Similarly, vibrant satisfaction is no longer as widespread as it used to be for Microsoft. Antagonistic groups, such as Linux fans, anti-trust agencies and industry lobbies, are creating resistance against this global technology group – they are Microsoft’s Desperados. Their persistent goal ixs to halt the firm’s customer momentum and erode its dominant position.11

Strategies for vibrant satisfaction

In chasing the goal of momentum, companies must systematically undertake actions to foster customer satisfaction and eradicate potential sources of friction. Remember MDC, the action roadmap to momentum introduced in the previous chapter. It is the key to accelerating an organization toward momentum at each stage of execution. To foster vibrant satisfaction, MDC will guide us through three steps – mobilize for vibrant satisfaction, detect sources of dissatisfaction and convert unsatisfied customers.

Mobilize for vibrant satisfaction

Vibrant customer satisfaction can be delivered only if a firm is united four-square behind this ambition. The objective should be clear and present to all levels of employees, from management to the front-line staff. At every moment of truth when the customer meets the firm, all employees must understand the significance of creating a resonant customer experience.

The central task of overhauling a corporate culture in order to set it on the rails of systematically stalking, enabling and accelerating customer momentum is so important that we devote all of Chapter 12 to exploring it in detail. Mobilizing staff to the goal of vibrant customer satisfaction is crucial, but it is not without its caveats – setting up this mobilization campaign requires care, consideration and intelligence. First, employees must trust the numbers, so they have to know how they are derived. Secondly, measuring customer satisfaction should be perceived not as a threatening or controlling mechanism, but rather as a tool for driving growth. Thirdly, employees will be inspired by details that are relevant to their experience. Many firms communicate nothing more than aggregate results, which are so far removed from the employees’ daily world that they are meaningless.

To see how very effective mobilization for customer satisfaction can be, consider Harrah’s Entertainment. Harrah’s invested $10 million in a major customer service initiative, which sought to fully understand the key drivers behind its customer’s perception of compelling value, and then redesigned its entire metrics system accordingly. For example, the general managers’ compensation system was changed so that a quarter of their bonus payments was contingent on customer satisfaction results. The casino trained staff specifically for customer service, paying extra wages for the training sessions. Every employee was rewarded if overall customer satisfaction scores improved by 3 per cent. In its first year the scheme paid out $7 million in bonuses. The following year the impact of the scheme contributed to a 15 per cent increase in revenues taking them up to $3.5 billion. Within four years $40 million had been paid out in bonuses, employee turnover had halved and revenue had more than doubled. Again, the story illustrates the importance of ambition. Although one casino topped the company’s satisfaction ratings for four consecutive quarters, its staff did not receive a bonus. Why? Because, although it was great, it had not shown any improvement. Momentum-powered firms make sure that the bar always rises.12

But it is important to recognize that there is more to mobilizing for vibrant satisfaction than financial rewards for staff. Obviously, stressing the central importance of customer satisfaction to business performance is unlikely to be successful if employees perceive that their contribution to that performance is not rewarded fairly. But there are other ‘rewards’ that arise from vibrant satisfaction and that energize employees strongly. The humans’ innate sense of fairness, the pride that comes from a job well done and the more pleasurable working environment that satisfied customers create are all strong momentum-building forces.

Detect sources of dissatisfaction

The gap between the design of a power offer and its execution can be enormous. Even the best companies get things wrong. This is why it is essential for firms to be humble enough to systematically hunt down all sources of dissatisfaction.

Tetra Pak offers an illustration of the importance of detecting what has gone wrong and where. This $10 billion company originated a power offer in the form of an aseptic carton for liquid food. This packaging revolutionized the industry, changed the consumption habits of millions of people, and secured 60 per cent of the global market for liquid food packaging.

As Tetra Pak grew larger and more successful, its growth and profitability came under threat in a maturing market and intense competition. The company began losing profitability, volume and customers. The situation was grave.

However, Tetra Pak was wise enough to realize that the key issue was not competition but its own relationship with its business customers. The company’s global survey showed that customer satisfaction was just above average. The rating was not so bad that it created a crisis, but it was not good enough to drive continued growth either. Critically, the dissatisfaction had nothing to do with the product itself. Customers were unhappy with Tetra Pak’s failure to help them to identify new sources of growth. According to the words used in the report, they were simply asking ‘Hear me, know me, grow me.’

Tetra Pak’s CEO used the survey results as a ‘burning platform’ from which to overhaul the company and bring it closer to customers. Sources of dissatisfaction were pitilessly analysed in detail. Tetra Pak engineers examined breakdown patterns of customers’ filling machines to boost operational cost efficiency, and within a few years machine breakdowns were halved. Tetra Pak regained momentum by creating vibrant satisfaction through opening new growth opportunities for its customers.13

It is not always easy for successful companies to spot the source of dissatisfaction, but with humility and effort they can always improve on the design and execution of an offer. The impact of customer dissatisfaction is too significant to be left to haphazard discovery – it must be sought out, actively and systematically. The insight discovery matrix presented in Chapter 4 is the right tool. Its four paths are also the appropriate routes for hunting customer dissatisfaction. For this purpose, it might be renamed the friction detection matrix.

The first of the four paths is the knowing–doing. It reflects an inexcusable blind spot for firms. If sources of dissatisfaction are known to both customers and the firm then they must be tackled instantly. The second path – listening to customers – is always the principal one. But some companies are beginning to realize that this path has even more potential than simply resolving complaints. Beyond raising problems to be resolved on an individual basis, customer complaints can become a valuable source of insights that lead to innovation. For example, Allianz, a leading global insurer, recognizes that if even a small proportion of its 75 million customers – say, 4 per cent – complain every year, these complaints represent 3 million opportunities for a double improvement in customer satisfaction – first by resolving the particular complaint, and second by applying the lessons learned to improve the experience offered to all customers.14

The third path, customer learning, can also be crucial, because sometimes dissatisfaction arises in customers not understanding the nature of offers or how they can be used effectively.

But the most challenging, and rewarding, path for companies tracking down customer dissatisfaction is the white one – the unknown virgin land blanketed in snow. If a source of dissatisfaction is obscure for both the firm and the customers then it will be very tricky to pinpoint. A helpful approach to resolving this problem is to imagine scenarios encompassing different customer experiences. These scenarios can be developed in workshops, in think tanks or via frameworks such as the customer activity cycle or the buyer experience cycle.15

Here’s a simple example. Amazon, the online book retailer, is frequently praised as an example of generating great customer satisfaction. It has built customer momentum on the back of a power offer and has incontestably created vibrant customer satisfaction. However, this doesn’t mean that it can’t be improved. To prove it, we did a little dissatisfaction hunt of our own and discovered one potential source of friction.

We selected a list of ten English language bestsellers by authors such as Stephen King, Jeffrey Archer and Dan Brown. We ordered the books, to be delivered to an identical delivery address in France, from both the Amazon UK site and the French site. Although the French site offers free delivery, it was 25 per cent more expensive for a French customer to order the books from France than to import them from the British site.16

Now, there may be myriad reasons to explain why Amazon.fr is more expensive, from exchange rates to internal transfer prices and regulations, but none of these would satisfy a disgruntled customer. It is the customer’s relationship with Amazon that is at stake.

A systematic hunt to identify and eradicate customer dissatisfaction should follow a planned, proactive programme rather than a reaction to crises or complaints – or, worse, a customer discovery like the one above. This hunt should be fed with a continuous allocation of resources and become part of a firm’s normal operations.

Convert unsatisfied customers

At the customer satisfaction stage, momentum is accelerated by converting Desperados and passive customers to Champions. Champions are customers who love the firm so much that they are likely to promote it and its offers. They have taken the first step that enables the firm to move them through the virtuous circle of retention and engagement, as we shall see in following chapters. This is the fulfilment of striving for vibrant satisfaction – converting customers to Champions. This is what builds the foundation for later stages of momentum. Ideally, the firm should aim at having no Desperados at all, and as few passive customers as possible. This ambitious objective is unattainable in full, but is an indispensable guiding principle nonetheless.

The tool for converting dissatisfied customers is called customer recovery, and it takes the hunt for dissatisfaction to the next level. Its first aim is to stop dissatisfied customers turning into Desperados. Once it has succeeded, it turns them into positive customers and then, ultimately, converts them to Champions.

Management should begin by encouraging employees to identify dissatisfied customers and empowering them to take corrective action. If they respond to a problem with something as simple as offering customers an alternative or a replacement for an item with which they are unhappy, this could be enough to lead to vibrant customer satisfaction. Customers will tell their story to friends and family, and will return. Some may even be transformed from Desperados into Champions.

A simple example can illustrate this point. Remember our simple calculation of the equity contained in what appears to be a simple $10 pizza-and-drinks transaction if that transaction is repeated once a week over a decade? $5000! Now imagine a customer in a pizzeria complaining that her pizza is burnt. The price of offering, on the spot, to make another pizza or of giving her a free drink is marginal compared to what’s at stake. Let’s pretend that the pizzeria staff did nothing to satisfy her complaint. What happens next? She leaves disgruntled and, next week, thinks nothing of trying the competitor on the next street.

How to get her back? The conventional method is through advertising. It’s a scattergun approach – the company hits people outside its target. Using advertising to bring dissatisfied customers back would cost hundreds of dollars per customer recovered. It may still be worth it given the customer equity at stake, but it’s an enormous price compared to the pittance that a free fresh pizza would have cost. One move is made at the source of the problem for a marginal cost of less than one dollar, with a high probability of success – the other takes place much later and costs hundreds of dollars, with much worse odds. It doesn’t take a financial genius to realize which is the best investment – and yet it rarely happens.

This highlights a paradox stemming from the vertical silos and linear processes that are hallmarks of momentum-deficient firms. On the one hand, there are site managers who put pressure on costs and who deliver margins by counting every cent. On the other, advertising managers are able to negotiate a budget based on last year plus 10 per cent, without counting one dime. Yet it is much more effective to educate all employees to act in a customer-focused manner, to create customer satisfaction and contribute to momentum growth.

The pizzeria example shows how targeted training could help employees identify and recover dissatisfied customers. A systematic approach is crucial. Momentum-powered companies understand the importance of recovering dissatisfied customers through appropriate responses. At Virgin Atlantic, responses to dissatisfied customers can range from a letter of apology or a bottle of champagne to a personal message from Richard Branson and free airline tickets – it all depends on the situation and the customer equity at stake.

At First Direct, agents have standing orders to drop everything until a customer’s complaint is fixed, calling in whatever resources are needed – even the CEO. The employee is highly motivated to get it done, get it done right and get it done fast. Almost without fail, the customer is happy and the bank has secured his or her goodwill in a natural and efficient way.

Problems are the test of a company’s relationship with its customers, in the same way that crises are a test of friendship in everyday life. Even satisfied customers won’t know an organization’s heart until they’ve experienced a problem. Problems encountered by customers make for the most memorable moments of truth. Dissatisfied customers who receive a good and fair response can become more loyal than those who never experienced a problem at all.

A case in point is JetBlue, the low-cost US airline, which delights its customers with an emphasis on inexpensive flying with great service. While other low-cost airlines focused on budget travellers and tourists, JetBlue also cast a spell over upscale business travellers and built incredible levels of customer commitment through exceptional service. Then JetBlue suffered a service meltdown in the winter of 2007. Not only were flights cancelled – in some cases, passengers were left in unheated planes on the tarmac in freezing conditions, for hours, with no food or drink. It was a customer service disaster.

The effectiveness of the recovery effort that followed is probably due to a number of factors – and the fact that JetBlue’s customers were more likely to be forgiving, at least once, because of their previous positive experiences. But the way JetBlue CEO David Neeleman handled the problem had a huge impact. He got out in front of as many TV cameras as possible and repeated his unequivocal apology and support for his staff. He repeated his promise that it wouldn’t happen again. He made that promise credible by setting out what the firm was doing to fix the problem and prevent a recurrence. And he announced an impressive compensation package, at a cost of over $20 million. He then took personal responsibility for the problem and, a few months later, resigned as CEO. This appears to have been enough to make sure that the wobble remained just that and didn’t become a blowout that wiped out momentum. For the second quarter of 2007, a period that began just a few days after the problem, JetBlue reported revenue growth of 19 per cent and profit growth of 50 per cent compared to the same quarter the year before. When the influential J.D. Power survey of North American airline customer satisfaction was published in June, four months after the debacle, who was ranked number one in the low-cost sector? JetBlue. Its customers had forgiven it.17

The examples above illustrate the three key steps of customer recovery. First, a firm should be close enough to its customers to detect sources of dissatisfaction as early as possible. It should have some ‘dissatisfaction nets’ in place to catch any problems that customers experience. These ‘nets’ can take the form of direct observation, quality controls, customer hotlines, easy reporting or surveys. They should identify disgruntled customers before they consider ending their relationship with the firm, or communicate their grief to other customers or prospects.

Secondly, apologize to the customer for the inconvenience. This should not only express recognition of the initial problem but also acknowledge the grief it has caused. It must be an affective response to an affective situation. Even if it is honest and accurate, a response that justifies the situation by logic at this stage will only aggravate the customer further.

Finally, following prompt analysis, the firm should compensate the customer in a way that will be perceived as better than fair. Not only does the damage have to be repaired – the response must be perceived as taking into account the added aggravations. There are, obviously, costs associated with such effective recoveries and the control systems that need to be established to avoid abuses, but they are small compared to the customer equity at stake, to the costs of acquiring new customers and to the impact on momentum. In most companies, investment in customer recovery has a higher financial return than any other investment alternative.

Nothing less than vibrant

Customer satisfaction is a crucial phase in the creation of momentum. It is the first test of the customer traction inherent in a power offer. Even if the power offer was properly designed and executed, there are always multiple unforeseen threats and opportunities that can significantly affect its impact. Furthermore, the inherent ‘dissatisfaction inside’ that drives customers behaviour is a permanent source of change and requires attention. However, the rewards are great. The more Champions a firm can enlist, the greater its momentum will be.

To maximize the potential momentum of a power offer at the customer satisfaction stage, this chapter has presented some guiding principles.

- Customer satisfaction is shaped every time customers encounter a firm, its products or its services. These moments of truth cumulatively become the customer experience.

- Satisfaction is a state of mind that becomes relevant only when it is so intense that it elicits an emotional response. It is these emotional responses that influence customers’ behaviour.

- Emotions are the reason why simple customer satisfaction does not create momentum but vibrant customer satisfaction does. As a result, momentum-powered firms set ambitious customer satisfaction objectives. To reach them, firms must use equally ambitious metrics, such as top-box satisfaction.

- Champions are customers who have positive emotions toward an offer and fuel its momentum. Desperados are customers who have negative emotions toward an offer and hinder its momentum.

- Customer satisfaction is an essential element of momentum. A specific programme of action is essential to systematically foster vibrant satisfaction that will further fuel the momentum created by a power offer. Firms must mobilize employees, detect sources of dissatisfaction and convert dissatisfied customers. Customer recovery is especially crucial to eradicate sources of dissatisfaction and to transform potential Desperados into Champions.

Building customer momentum is a continuous task. Firms must constantly strive to reach higher and higher standards of satisfaction – only the top box will do. But even vibrant satisfaction is not enough on its own – momentum requires that customers repeatedly buy the power offer. This – vibrant retention – is the next phase in the virtuous circle, and the subject of the next chapter.